Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate the correlation between transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β1) expression and prognosis in prostate cancer.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

TGF-β1 expression levels were analyzed using the quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction to amplify RNA that had been isolated from fresh-frozen malignant and benign tissue specimens collected from 89 patients who had clinically localized prostate cancer and had been treated with radical prostatectomy. The control group consisted of 11 patients with benign prostate hyperplasia. The expression levels of TGF-β1 were compared between the groups in terms of Gleason scores, pathological staging, and prostate-specific antigen serum levels.

RESULTS:

In the majority of the tumor samples, TGF-β1 was underexpressed 67.0% of PCa patients. The same expression pattern was identified in benign tissues of patients with prostate cancer. Although most cases exhibited underexpression of TGF-β1, a higher expression level was found in patients with Gleason scores ≥7 when compared to patients with Gleason scores <7 (p = 0.002). Among the 26 cases of TGF-β1 overexpression, 92.3% had poor prognostic features.

CONCLUSIONS:

TGF-β1 was underexpressed in prostate cancers; however, higher expression was observed in tumors with higher Gleason scores, which suggests that TGF-β1 expression may be a useful prognostic marker for prostate cancer. Further studies of clinical specimens are needed to clarify the role of TGF-β1 in prostate carcinogenesis.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Prognosis, Molecular markers, TGF-β

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common male malignancy and is the second-highest cause of death in many countries, including Brazil.1 Pathological staging, Gleason scores, and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) serum levels are the most reliable prognostic factors; however, even when combined, they do not perfectly identify patients who are at risk of progression.2 Therefore, research has been aimed at identifying molecular markers that can predict PCa predisposition and progression.

Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) is the prototypical member of a superfamily that includes more than 25 members, including inhibin, bone morphogenetic protein, and Müllerian inhibiting substance. The TGF-β subfamily contains five members named TGF-β1 through β5. TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3 have been identified in mammals.3,4 Although TGF-β is a pleiotropic growth factor, it inhibits growth in most cell types, especially cells of epithelial lineage. TGF-β also inhibits prostatic epithelial cell proliferation and induces apoptosis.5,6 In addition to its numerous effects on cell proliferation, phenotype, and differentiation,7 TGF-β is an important transcriptional regulator of extracellular matrix components.

Malignant transformation is characterized by multiple genetic mutations that confer a growth advantage to transformed cells compared with benign cells. The development of prostate cancer follows this paradigm. TGF-β is involved in two critical events that are consistently associated with the conversion from a benign state to a malignant state: 1) a reduction or loss of the sensitivity to the inhibitory effects of TGF-β and 2) an increase in the ability to elevate TGF-β expression levels, which in turn promotes carcinogenesis by stimulating extracellular matrix production, promoting angiogenesis, and inhibiting the host immune system.8

To evaluate whether the expression levels of TGF-β1 in prostate cancer cells are associated with prognosis, as predicted by the TGF-β elevation in carcinogenesis, we investigated a putative correlation between TGF-β gene expression and Gleason score, pathological stage, and PSA serum level.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

This study was conducted using surgical specimens from 79 patients with clinically localized PCa who underwent radical prostatectomy in our institution between 1993 and 2007; patients with a minimum follow-up of five years were randomly selected from a frozen tumor tissue database (Table 1). Benign tissue samples from an additional 10 patients with PCa who also underwent radical prostatectomy were included in this group. Patients who had undergone other treatments for PCa were excluded. All of the subjects provided their informed consent to participate in the study and to allow their biological samples to be genetically analyzed. Approval for the study was given by the Institutional Board of Ethics (n°0453/08).

Table 1.

Age and clinical characteristics of 79 men who underwent radical prostatectomy to treat prostate cancer.

| Age (years) | |

| Mean | 63 |

| Min - Max | 41 - 79 |

| PSA (ng/ml) | |

| Mean | 10.8 |

| Min - Max | 2.0 - 37.0 |

| <10 n (%) | 47 (59.5) |

| ≥10 n (%) | 32 (40.5) |

| Stage | |

| pT2 n (%) | 38 (48) |

| pT3 n (%) | 41 (52) |

| Gleason Score | |

| <7 n (%) | 32 (41.7) |

| ≥7 n (%) | 46 (58.3) |

We correlated the expression levels of the TGF-β1 genes in each sample with the patient's Gleason score, pathologic stage according to the TNM 2002 staging system, and serum PSA level (in ng/ml). For the analysis, the pathologic stage was considered as an organ-confined (pT2) or non-organ-confined (pT3) disease. The Gleason score was classified as low grade (<7) or high grade (≥7), and preoperative PSA was used to identify patients at high (≥10 ng/ml) or low risk (<10 ng/ml) for disease recurrence. In addition, at a mean follow-up time of 60 months, we analyzed the gene expression levels in patients with biochemical recurrence, which was defined as a PSA level >0.4 ng/ml.

The control group consisted of tissue specimens from 11 patients with benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) who presented with lower urinary tract symptoms and had an interest in undergoing surgery (mean age 64±6.0 years).

RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

All of the tumor samples were obtained from surgical specimens and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen at -170°C. A mirror image slide of the frozen fragment was stained with hematoxylin and eosin to verify that the tumor represented at least 75% of the fragment in the cancer patients and that no tumors were present in the control patients with BPH.

Total RNA was isolated using the RNAaqueous Kit (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA concentration was determined by the ratio of the absorbance at 260 and 280 nm using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). cDNA was generated using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). The reactions were incubated at 25°C for 10 min, followed by 37°C for 120 min and 85°C for 5 min. The cDNA was stored at -20°C until use.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction and Gene Expression

The expression level of the TGF-β1 gene was analyzed using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) with the ABI 7500 Fast system (Applied Biosystems). The target sequences were amplified in a 10 µl reaction volume containing 5 µl TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, 0.5 µl TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (TGF-β Hs00852894_m1 and B2M Hs99999907_m1), 1 µl cDNA, and 3.5 µl DNase-free water. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cycling conditions were 2 min at 50°C and 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C. The TaqMan endogenous control assay utilized β-2-microglobulin (B2M).

We used the ΔΔCT method to calculate the relative expression levels of the two target genes using the formula ΔΔCT = (CT target gene, PCa sample - CT endogenous control, PCa sample) – (CT target gene, BPH sample - CT endogenous control, BPH sample). The fold change in gene expression was calculated as 2-ΔΔCT.

Statistical Analyses

Quantitative variables were expressed as median values, interquartile ranges (Q1-Q3), and minimum and maximum values. Qualitative variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. We constructed a box plot for a descriptive analysis of TGF-β expression according to pathologic stage, Gleason score, and PSA level. We used the Mann-Whitney test to compare categories. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 3, and significance was set at p≤0.05.

RESULTS

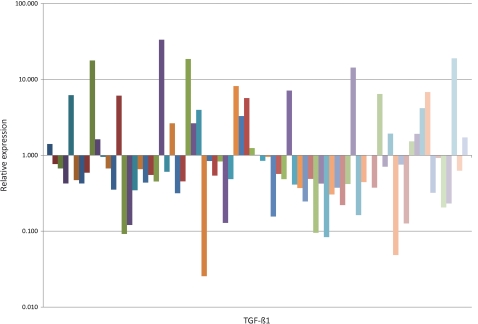

As shown in Figure 1, an analysis of the 79 patients with PCa showed that TGF-β1 was underexpressed (median 6.07×10-1-fold) in malignant prostatic tissue as compared to the BPH samples.

Figure 1.

Quantitative expression of TGF-β1 messenger RNA in malignant prostatic tissue compared with BPH. Fold change in expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method.

The TGF-β1 expression levels in relation to the Gleason scores are shown in Table 2. The median TGF-β1 expression levels were significantly higher (p = 0.0065) among patients with a Gleason score ≥7 (9.4×10-1-fold) compared with those patients with a Gleason score <7 (4.6×10-1-fold). With regard to the pathologic stage, the expression of TGF-β1 was similar (p = 0.2514) between stage pT3 patients (median 4.9×10-1-fold) and stage pT2 patients (median 6.6×10-1-fold). When the results were evaluated according to preoperative PSA values, the median TGF-β1 expression levels were also similar (p = 0.5110) between patients with PSA levels ≥10 ng/ml (6.7×10-1-fold) and patients with PSA levels <10 (5.5×10-1-fold).

Table 2.

Relative expression of the TGF-β1 gene in the malignant prostatic tissues according to Gleason score, pathologic stage, PSA level and biochemical recurrence. Fold changes in gene expression were calculated using the ΔΔCT method (QRel = 2-ΔΔCT).

| TGF-β1 | |

| Gleason Score | |

| <7 (n = 32) | 0.46 (0.02 - 6.20) |

| ≥7 (n = 36) | 0.93 (0.02 - 33.3) |

| p-value | 0.006 |

| Pathologic Stage | |

| pT2 (n = 37) | 0.65 (0.02 - 33.3) |

| pT3 (n = 40) | 0.48 (0.04 - 18.9) |

| p-value | 0.249 |

| PSA Level | |

| <10 (n = 45) | 0.55 (0.04 - 33.3) |

| ≥10 (n = 33) | 0.67 (0.02 - 14.3) |

| p-value | 0.508 |

| Biochemical Recurrence | |

| Without (n = 29) | 0.60 (1.12 - 33.3) |

| With (n = 28) | 0.54 (0.04 - 18.9) |

| p-value | 0.523 |

We found an overexpression of TGF-β1 in 26 cases, of which 21 (80.7%) had a Gleason score ≥7, 13 (50%) had a PSA level ≥10 ng/ml, 12 (46%) were staged as pT3 and 9 (35%) had biochemical recurrence. Only 2 (7.7%) of the patients with TGF-β1 overexpression exhibited no unfavorable prognostic factors.

We also evaluated the expression levels of TGF-β1 in patients with biochemical recurrence (which was defined as a PSA level above 0.4 ng/ml) at a mean follow-up period of 60 months. Median TGF-β1 expression levels were statistically similar (p = 0.528) among patients with and without recurrence (5.4×10-1 and 6.1×10-1, respectively).

We performed a multivariate analysis, and the Gleason score was the unique independent prognostic factor in our series (p = 0.022).

Additionally, we tested the expression of TGF-β1 in the prostatic tissues from 10 patients with benign PCa and found the same expression patterns as observed in the malignant tissues (median 1.7×10-1) (p = 0.05).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that TGF-β1 was underexpressed in malignant prostatic tissue as compared to BPH samples (median 7×10-1-fold). Thus, we may assume that TGF-β contributes to the development of prostate cancer by acting as an inhibitor of cell proliferation and an inducer of apoptosis.8,9 Furthermore, we identified higher TGF-β expression levels in tumors with higher Gleason scores, suggesting that this gene may play a role in PCa progression and prognosis.

Soulitzis et al10 also reported a decrease in TGF-β expression in PCa. TGF-β is generally a growth inhibitor of both benign prostatic epithelial cells11 and prostate cancer cells in vitro12 and has been shown to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in prostatic epithelial cells.8,13

Moreover, TGF-β stimulates the synthesis of collagen, fibronectin, and integrins, and it inhibits matrix degradation through the downregulation of proteinases such as collagenases, stromelysins, and plasminogen activators.14 Paired with its downregulation of proteinases, TGF-β upregulates proteinase inhibitors such as the following endogenous matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) inhibitors: the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1)15 and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1.16 TGF-β also acts as a repressor of matrix metalloproteinase expression through the TGF-β inhibitory element (TIE), which is found in the 5′-flanking region of several genes in the MMP family, namely interstitial collagenase (MMP-1) and 92-kDa type IV collagenase (MMP-9).17

Interestingly, a quantitative analysis revealed a positive association between increased TGF-β1 mRNA levels and elevated Gleason scores (p = 0.002). Although controversial, this finding is consistent with that of a previous study in which TGF-β plasma levels were higher in men with PCa metastases than in healthy men.18 Shariat et al19 also found a strong correlation between elevated plasma TGF-β and prostate cancer progression and the development of metastases in patients with locally advanced disease. Faria et al20 demonstrated that among patients with PCa, the relative levels of TGF-β1 mRNA increased during the late stages of the disease.

Some studies have suggested that decreased expression of TGF-β is not entirely necessary, as some tumor cells might escape the inhibitory effects of TGF-β through mutations that could provide a growth advantage over their benign counterparts. It has also been established that both TGF-β receptors (TβR-I and TβR-II) are required for the proper transduction of TGF-β signaling,21 and prostate cancer cells might reduce the expression or function of either TβR-I or TβR-II to escape the growth-inhibiting effects of TGF-β. This loss of sensitivity to TGF-β by its receptors could induce a compensatory overexpression of TGF-β, thereby leading to more aggressive phenotypes.22

Research has suggested that whether TGF-β exerts a tumor-suppressive or oncogenic effect is contextual and/or depends upon the temporal stage of cellular transformation.23 A recent study reported that the activation of TGF-β signaling pathways might be responsible for mediating the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), thereby enhancing the invasiveness and survival of transformed cells.24 Moreover, TGF-β can alter the host-tumor interaction, thus facilitating tumor growth, promoting angiogenesis, and inhibiting the host immune system.9,25

By examining benign tissues from the removed prostates of patients with PCa who were treated by radical prostatectomy, we observed the same TGF-β expression pattern as in malignant tissue. This result is interesting because it allows us to propose the use of TGF-β as a tumor marker, thereby overcoming the sampling error that commonly occurs in conventional prostate biopsies; however, larger studies should be conducted to further validate our findings.

In conclusion, we showed for the first time in clinical specimens that decreased expression of TGF-β is a characteristic of prostate cancer and may be related to cancer initiation and promotion; the role of TGF-β as a regulator of cell growth and apoptosis should be confirmed in a wider series. On the other hand, TGF-β superexpression might be related to tumor progression, as it is more highly expressed in more aggressive tumors, and this finding could be explained by mutations that confer resistance to TGF-β receptors. This hypothesis also warrants further experimental studies to analyze the potential of TGF-β as a diagnostic or prognostic marker.

Grant sponsors: This study was supported by FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Sao Paulo) under protocol number 2009/50368-9.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–49. Epub 2009 May 27. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. 10.3322/caac.20006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Partin AW, Kattan MW, Subong EN, Walsh PC, Wojno KJ, Oesterling JE, et al. Combination of prostate-specific antigen, clinical stage, and Gleason score to predict pathological stage of localized prostate cancer. A multi-institutional update. JAMA. 1997;277:1445–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derynck R, Jarret JA, Chen EY, Eaton DH, Bell JR, Assoian RK, et al. Human transforming growth factor-b complementary DNA sequences and expression in normal and transformed cells. Nature. 1985;316:701–5. doi: 10.1038/316701a0. 10.1038/316701a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madison L, Webb NR, Rose TM, Marquardt H, Ikeda T, Twardzik D, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 2: cDNA cloning and sequence analysis. DNA. 1988;7:1–8. doi: 10.1089/dna.1988.7.1. 10.1089/dna.1988.7.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutkowski DM, Fong C-J, Sensibar JA, Rademaker AW, Sherwood ER, Kozlowski JM, et al. Interaction of epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-b1 in human prostatic epithelial cells in culture. Prostate. 1992;21:133–43. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990210206. 10.1002/pros.2990210206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilding G. Response of prostate cancer cells to peptide growth factor: transforming growth factor-b. Cancer Surv. 1991;11:147–63. 10.3167/001115799782483762 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexandrow MG, Moses HL. Transforming growth factor β and cell cycle regulation. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1452–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee C, Sintich SM, Mathews EP, Shah AH, Kundu SD, Perry KT, et al. Transforming Growth Factor-β in Benign and Malignant Prostate. The Prostate. 1999;39:285–90. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19990601)39:4<285::aid-pros9>3.0.co;2-7. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(19990601)39:4<285::AID-PROS9>3.0.CO;2-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang EY, Moses HL. Transforming growth factor b1-induced changes in cell migration, proliferation, and angiogenesis in the chicken chorioallantoic membrane. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:731–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.2.731. 10.1083/jcb.111.2.731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soulitzis N, Karyotis I, Delakas D, Spandidos D. Expression analysis of peptides growth factors VEGF, FGF2, TGFβ1, EGF and IGF1 in prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int. Journal of Oncology. 2006;29:305–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sutkowski DM, Fong C-J, Sensibar JA, Rademaker AW, Sherwood ER, Kozlowski JM, et al. Interaction of epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-b1 in human prostatic epithelial cells in culture. Prostate. 1992;21:133–43. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990210206. 10.1002/pros.2990210206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilding G. Response of prostate cancer cells to peptide growth factor: transforming growth factor-b. Cancer Surv. 1991;11:147–63. 10.3167/001115799782483762 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martikainen P, Kyprianou N, Isaacs JT. Effect of transforming growth factor-b1 on proliferation and death of rat prostatic cells. Endocrinology. 1990;127:2963–8. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-6-2963. 10.1210/endo-127-6-2963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franzèn P, Ichijo H, Miyazono K. Different signals mediate transforming growth factor-beta 1-induced growth inhibition and extracellular matrix production in prostatic carcinoma cells. Exp Cell Res. 1993;207:1–7. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1156. 10.1006/excr.1993.1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edwards DR, Leco KJ, Beaudry PP, Atadja PW, Veillette C, Riabowol KT. Differential effects of transforming growth factor-beta1 on the expression of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in young and old human fibroblasts. Exp Gerontol. 1996;31:207–23. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(95)02010-1. 10.1016/0531-5565(95)02010-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnoletti JP, Albo D, Granick MS, Solomon MP, Castiglioni A, Rothman VL, et al. Thrombospondin and transforming growth factor-beta 1 increase expression of urokinase-type plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in human MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Cancer. 1995;76:998–1005. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950915)76:6<998::aid-cncr2820760613>3.0.co;2-0. 10.1002/1097-0142(19950915)76:6<998::AID-CNCR2820760613>3.0.CO;2-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinase gene expression. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994;732:42–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb24723.x. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb24723.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shariat SF, Menesses-Diaz A, Kim IY, Muramoto M, Wheeler TM, Slawin KM. Tissue expression of transforming growth factor-eta1 and its receptors: correlation with pathologic features and biochemical progression in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2004;63:1191–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.12.015. 10.1016/j.urology.2003.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shariat SF, Kattan MW, Traxel E, Andrews B, Zhu K, Wheeler TM, et al. Association of pre and postoperative plasma levels of transforming growth factor beta(1) and interleukin 6 and its soluble receptor with prostate cancer progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1992–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0768-03. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0768-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faria PC, Saba K, Neves AF, Cordeiro ER, Marangoni K, Freitas DG, Goulart LR. Transforming Growth Factor-Beta1 gene polymorphisms and expression in the blood of Prostate Cancer patients. Cancer investigation. . 2007;725:726–32. doi: 10.1080/07357900701600921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wrana JL, Attisano L, Wieser R, Ventura F, Massague J. Mechanism of activation of the TGF-b receptor. Nature. 1994;370:341–7. doi: 10.1038/370341a0. 10.1038/370341a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrack ER. TGF-b on prostate cancer: a growth inhibitor that can enhance tumorigenicity. Prostate. 1997;31:61–70. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19970401)31:1<61::aid-pros10>3.0.co;2-m. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(19970401)31:1<61::AID-PROS10>3.0.CO;2-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bello-DeOcampo D, Tindall DJ. TGF-betal/Smad signaling in prostate cancer. Curr Drug Targets. 2003;4:197–207. doi: 10.2174/1389450033491118. 10.2174/1389450033491118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prindull G, Zipori D. Environmental guidance of normal and tumor cell plasticity: epithelial mesenchymal transitions as a paradigm. Blood. 2004;103:2892–99. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2807. 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Letterio JJ, Roberts AB. Regulation of immune responses by TGF-b. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:137–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.137. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]