Abstract

PURPOSE:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of dexmedetomidine on shivering during spinal anesthesia.

METHODS:

Sixty patients (American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I or II, aged 18-50 years), scheduled for elective minor surgical operations under spinal anesthesia with hyperbaric bupivacaine, were enrolled. They were administered saline (group C, n = 30) or dexmedetomidine (group D, n = 30). Motor block was assessed using a Modified Bromage Scale. The presence of shivering was assessed by a blinded observer after the completion of subarachnoid drug injection.

RESULTS:

Hypothermia was observed in 21 patients (70%) in group D and in 20 patients (66.7%) in group C (p = 0.781). Three patients (10%) in group D and 17 patients (56.7%) in group C experienced shivering (p = 0.001). The intensity of shivering was lower in group D than in group C (p = 0.001). Time from baseline to onset of shivering was 10 (5-15) min in group D and 15 (5-45) min in group C (p = 0.207).

CONCLUSION:

Dexmedetomidine infusion in the perioperative period significantly reduced shivering associated with spinal anesthesia during minor surgical procedures without any major adverse effect during the perioperative period. Therefore, we conclude that dexmedetomidine infusion is an effective drug for preventing shivering and providing sedation in patients during spinal anesthesia.

Keywords: Dexmedetomidine, Shivering, Spinal anesthesia

INTRODUCTION

Shivering is defined as an involuntary, repetitive activity of skeletal muscles. The mechanisms of shivering in patients undergoing surgery are mainly intraoperative heat loss, increased sympathetic tone, pain, and systemic release of pyrogens.1 Spinal anesthesia significantly impairs the thermoregulation system by inhibiting tonic vasoconstriction, which plays a significant role in temperature regulation.2 Spinal anesthesia also causes redistribution of core heat from the trunk (below the block level) to the peripheral tissues. These two effects predispose patients to hypothermia and shivering.3 The median incidence of shivering related to regional anesthesia observed in a review of 21 studies is 55%.1 Shivering increases oxygen consumption, lactic acidosis, carbon dioxide production, and metabolic rate by up to 400%.4,5 Therefore, shivering may cause problems in patients with low cardiac and pulmonary reserves. The best way to avoid these intraoperative and postoperative shivering-induced increases in hemodynamic and metabolic demands is to prevent shivering in the first place.1 Although dexmedetomidine is among several pharmacological agents used for the treatment of shivering, its effects on prevention of shivering during central neuraxial blockade have not been evaluated to date. Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective α2-adrenoceptor agonist with potent effects on the central nervous system.6-8 Henceforth, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of dexmedetomidine on shivering during spinal anesthesia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sixty patients (American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I or II, aged 18-50 years), scheduled for elective minor surgical operations under spinal anesthesia, were enrolled in the study. Patients with thyroid disease, Parkinson's disease, dysautonomia, Raynaud's syndrome, cardiopulmonary disease, a history of allergy to the agents to be used, a need for blood transfusion during surgery, an initial core temperature >37.5°C or <36.5°C, a known history of alcohol use, use of sedative-hypnotic agents, use of vasodilators, or having contraindications to spinal anesthesia were excluded from the study. The Local Ethics Committee approved the study protocol, and all subjects gave written consent to participate. The temperature of the operating room was maintained at 21°C to 22°C (measured by a wall thermometer). Irrigation and i.v. fluids were administrated at room temperature and given without in-line warming. All patients were covered with one layer of surgical drapes over the chest, thighs, and calves during the operation and then one cotton blanket over the entire body postoperatively. No other warming device was used. A core temperature below 36°C was considered hypothermia. Before performing spinal anesthesia, each patient received 10 ml kg-1h-1 of lactated Ringer's solution. The infusion rates were then reduced to 6 ml kg-1h-1. Following the guidelines for asepsis and antisepsis, subarachnoid anesthesia was instituted at either the L3-4 or L4-5 interspaces. A volume of 3 ml of hyperbaric bupivacaine (Marcaine® Spinal Heavy 0.5%, AstraZeneca, Istanbul, Turkey) was injected using a 25 G Quincke spinal needle (Typo Healthcare, Gasport, UK). The patients were randomized to one of two groups by sequentially numbered envelopes, which designated them to receive saline (group C, n = 30) or dexmedetomidine (group D, n = 30). An investigator who was not otherwise involved in the study prepared syringes containing saline or dexmedetomidine; thus, the study was double-blinded. Just after intrathecal injection, all drugs were infused intravenously. Dexmedetomidine (Precedex®, Meditera, Istanbul, Turkey) was diluted to a volume of 50 ml (4 µg ml-1) and presented as coded syringes by an anesthesiologist. Group D was given an i.v. bolus of dexmedetomidine 1 µg kg-1 administered by a syringe pump (Perfuser compact, Braun, Germany) over a 10-min period followed by an infusion of 0.4 µg kg-1h-1 dexmedetomidine during the surgery. Group C received an equal volume of saline. The infusions were stopped at the completion of the closure of the skin. Supplemental oxygen (2 l min-1) was delivered via a facemask during the operation. Motor block was assessed using a modified Bromage scale (0, no motor block; 1, hip blocked; 2, hip and knee blocked; 3, hip, knee, and, ankle blocked). Full motor recovery was scored as 0 on the Bromage scale. Sensorial block was assessed by the pinprick test. The levels of motor and sensory blockade were assessed during the intraoperative period. The presence of shivering was assessed by a blinded observer after the completion of subarachnoid drug injection. Shivering was graded on a scale similar to that validated by Tsai and Chu:4 0 = no shivering, 1 = piloerection or peripheral vasoconstriction but no visible shivering, 2 = muscular activity in only one muscle group, 3 = muscular activity in more than one muscle group but not generalized, and 4 = shivering involving the whole body. The incidence and severity of shivering were recorded at 5-min intervals during the operation and in the recovery room. If scores were three or greater at 15 minutes after spinal anesthesia, the prophylaxis was regarded as ineffective, and 25 mg pethidine was administered by i.v. Side effects, such as headache, allergy, hypotension, bradycardia, waist and back pain, sedation score, total spinal block, and difficulty in micturition, nausea and vomiting were recorded. If the patient's heart rate fell below 50 bpm, 0.5 mg atropine was administered by i.v. Hypotension was defined as a decrease in the mean arterial pressure (MAP) of more than 20 % from baseline (baseline MAP was calculated from three measurements taken in the ward before surgery). Hypotension was treated with 10 mg ephedrine via i.v. bolus and then with further i.v. infusion of lactated Ringer's solution as required. The quantity of ephedrine given in each group was recorded. If patients developed nausea and vomiting, 10 mg metoclopramide was administered through the i.v. Postoperatively, all patients were monitored, given oxygen via a facemask and were covered with one layer of drapes and one cotton blanket. The post-anesthesia care unit temperature was maintained at 25°C to 26°C and constant humidity. If shivering scores were greater than or equal to 3, 25 mg pethidine was administered through the i.v. The attending anesthesiologist also assessed the degree of sedation on a 5-point scale: 1 = fully awake and oriented, 2 = drowsy, 3 = eyes closed but open on command, 4 = eyes closed but open to mild physical stimulation, and 5 = eyes closed and unresponsive to mild physical stimulation.10

SPSS 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to analyze all statistical data. Sample size estimation was based on our preliminary study to detect shivering in 15% of patients using the 2-sided t test with alpha = 0.05 and a power of 80%. Quantitative variables were compared between groups using Student's t-test or a Mann-Whitney U-test where appropriate. Within-group data for core temperature were analyzed by using repeated-measures analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc testing. Within-group data for heart rate and mean arterial pressure were analyzed using a Friedman test. Chi-square analysis was used for comparison of categorical variables. The results are shown as median (range), mean (±SD), exact numbers or proportions are expressed as a percentage. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

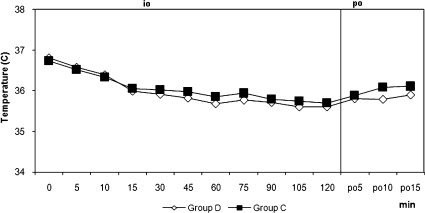

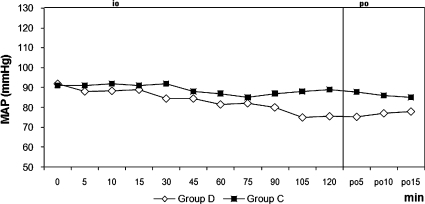

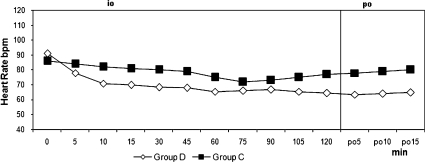

The two groups were similar regarding age, weight, height, duration of surgery, duration of motor block, and duration of sensorial block (Table 1). Hypothermia was observed in 21 patients (70%) in group D and in 20 patients (66.7 %) in group C (p = 0.781). The core temperature of patients was not different between the groups during the intraoperative or postoperative periods (Figure 1). Three patients (10%) in group D and 17 patients (56.7%) in group C experienced shivering (p = 0.001). One patient had Grade 1 and two patients had Grade 2 shivering in group D. The intensity of shivering was lower in group D than in group C (p = 0.001), and Grade 4 shivering was not noted in any patient in either group. Patients' shivering scores are given in Table 2. There were no statistically significant differences for the mean onset times of shivering between groups, which were 10 (5-15) min in group D and 15 (5-45) min in group C (p = 0.207). However, there were statistically significant differences for sedation between groups, all patients in group D and six patients in group C were in levels 3-5 of sedation (p = 0.001). Mean arterial pressures and hearth rates were lower in group D following the infusion of dexmedetomidine during the intra and postoperative periods (Figures 2 and 3). Although five patients in group C needed meperidine (25 mg, i.v.) to treat shivering, no patients in group D needed this treatment. Three patients in group D and one patient in group C were given 0.5 mg atropine. One patient in group D was given 10 mg ephedrine by i.v. during the operation. There were no statistically significant differences for adverse events between groups (Table 3). Two patients in group D and one patient in group C had nausea. Two patients in group D and one patient in group C had difficulty in micturition in the first 24 hours following spinal anesthesia. During the one-week follow-up interview, one patient in each group reported headache with equivocal characteristics of a postural puncture headache, both of which resolved with conservative management.

Table 1.

Demographic and intraoperative variables of the subjects - medians and ranges.

| DexmedetomidineGroup(n = 30) | ControlGroup(n = 30) | p-value | |

| Gender (male/female) | 24/6 | 23/7 | 0.754 |

| Age (year) | 36 (20-50) | 37 (20-50) | 0.906 |

| Height (cm) | 170 (156-188) | 173 (153-188) | 0.524 |

| Weight (kg) | 80 (50-90) | 80 (51-90) | 0.784 |

| Duration of surgery (minutes) | 65 (25-225) | 68 (15-150) | 0.917 |

| Duration of motor block (minutes) | 220 (75-460) | 180 (95-430) | 0.739 |

| Duration of sensorial block (minutes) | 237 (90-470) | 212 (100-470) | 0.900 |

| Total dose of Dexmedetomidine (µg) | 108 (80-160) | ||

| Sensory block Onset at T12 pinprick (minutes) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3-5) | |

| Motor block Time to grade 3 block (minutes) | 3.2 (2-4.5) | 3.3 (2-4.7) | |

| Types of operation | |||

| Varicose vein | 8 | 9 | |

| Umbilical hernia | 2 | 3 | |

| Arthroscopy | 10 | 10 | |

| Bladder tumor | 5 | 4 | |

| Ureterorenoscopy | 5 | 4 |

There were no significant differences among the groups.

Figure 1.

Tympanic Core Temperatures. io: intraoperative, po: postoperative, min: minute, The tympanic core temperatures at each time interval were similar among the groups.

Table 2.

Perioperative shivering scores of the patients.

| Shivering score | Group D (n = 30) | Group C (n = 30) |

| 0 | 27* | 13 |

| 1 | 1 | 7 |

| 2 | 2 | 5 |

| 3 | 0 | 5 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 |

*p = 0.001 (Chi-square test).

*p = 0.001 compared with the other groups using the Chi-square test.

Figure 2.

Mean Arterial Pressures. MAP: Mean Arterial Pressure, io: intraoperative, po: postoperative, min; minute, Intraoperative and postoperative mean arterial pressure. +<0.05 when two groups are compared.

Figure 3.

Heart Rates. io: intraoperative, po: postoperative, min; minute, Intraoperative and postoperative heart rate. +p<0.05 when two groups are compared, *p<0.05 compared with baseline value.

Table 3.

Patients' perioperative adverse events.

| Adverse events | Group D (n = 30) | Group C (n = 30) |

| Total spinal block | 0 | 0 |

| Allergy | 0 | 0 |

| Hypotension | 1 | 0 |

| Nausea- vomiting | 2 | 1 |

| Bradycardia | 3 | 1 |

| Difficulty in micturition | 2 | 1 |

| Post-punctural headache | 1 | 1 |

| Back pain | 0 | 0 |

There were no significant differences for adverse events between the groups.

DISCUSSION

We found that dexmedetomidine infusion effectively decreased the incidence and severity of shivering related to regional anesthesia during elective minor surgeries. The exact mechanism of shivering during regional anesthesia has not been fully established. The possible mechanisms include cessation of central thermoregulation, internal redistribution of body heat, and heat loss to the environment.2,11,12 Redistribution of core temperature during regional anesthesia is typically restricted to the legs, and therefore core temperature decreases about half as much during regional anesthesia as during general anesthesia.11 Vasoconstriction and shivering are restricted to the upper body during spinal anesthesia, as they are inhibited below the level of blockade through sympathetic and somatic neural block.12 In contrast to these changes, vasoconstriction and shivering are restricted to the upper body during spinal anesthesia. The median incidence of shivering related to neuraxial anesthesia in the control groups of 21 studies is 55 % (interquartile range of 40-64%),1 which is nearly similar to that of the control group in our study (63.4%). As shivering is a response to hypothermia, body temperature should be normally maintained within the normal limits of 36.5-37.5°C.13 Major risk factors in regional anesthesia for hypothermia are aging, level of sensory block, and temperatures of the operating room and intravenous solutions.14 In our study, the temperature of the operating room was maintained at 21-22°C, and all fluids and drugs were at room temperature during the surgery. Various drugs have been used to treat or prevent postoperative shivering. However, dexmedetomidine may be a good choice among them because of its dual effects of anti-shivering and sedation. Pharmacological therapies, such as pethidine, tramadol, physostigmine, clonidine, ketamine, and magnesium, have been used to prevent shivering.15-17 Although clonidine has been used safely and effectively to treat shivering, other drugs, such as urapidil,14 may not be appropriate because the incidence of hypotension is high during spinal anesthesia. Dexmedetomidine, on the other hand, is a short acting α2 mimetic with less hypotensive effect and an added a sedative effect. Meperidine, the most widely used agent to prevent shivering, may cause nausea and vomiting as well as respiratory depression during and after spinal anesthesia.18 Hypertensive and tachycardic effects of ketamine have also been reported.19 The search continues for drugs that sufficiently improve the tolerance of thermoregulation without simultaneously producing excessive sedation, respiratory depression, or hemodynamic instability. Dexmedetomidine is used for the sedation of mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. Thus, it has been rarely used for the prevention of vasoconstriction and shivering during spinal anesthesia.8,9,

Dexmedetomidine displays specific and selective α2-adrenoceptor agonism in the brain and spinal cord. The responses to activation of these receptors include decreased sympathetic tone with attenuation of the neuroendocrine and hemodynamic responses to anesthesia and surgery. Thus, dexmedetomidine can mediate both the beneficial and unwanted effects of shivering provoked by hypothermia, such as increased catecholamine concentrations, oxygen consumption, blood pressure, and heart rates.6,23,24

Dexmedetomidine exerts its dual effects while avoiding vasoconstriction and increasing the level of the shivering threshold, but meperidine, only increases the shivering threshold in healthy volunteers.22,25 In contrast to our results, Coskuner et al26 did not observe shivering with the same dose that we used in our study. Also, Elvan and colleagues8 reported that dexmedetomidine infusion during surgery was effective in the prevention of post-anesthetic shivering in patients undergoing elective abdominal hysterectomy. Bicer and colleagues21 found the incidence of shivering as 15% with dexmedetomidine and 55% with placebo following general anesthesia. Our results are similar to their study with the incidences being 10% and 56.7%, respectively. The lower incidence of shivering in the dexmedetomidine group may be related to the depression of the thermoregulation threshold. A limitation of our study was that we did not assess different doses of dexmedetomidine; further studies are needed to evaluate the effects of dexmedetomidine with various doses. The hemodynamic effects of dexmedetomidine are biphasic. When it is administered through an i.v., it causes hypotension and bradycardia until central sympathomimetic effect is achieved, and then it causes moderate decreases in MAP and HR.27,28 In our study, the mean arterial pressures were lower after the start of the infusion especially at 105 and 120 minutes during the surgery. HR was found to be significantly lower in the dexmedetomidine group when compared with the control group beginning from the 5th minute of infusion until the end of the blockade. Furthermore, while the incidence of bradycardia was 10% in group D, one patient developed bradycardia in group C. One of the main objectives in using sedative agents is that the drug should not cause respiratory depression. In previous studies, it has been shown that α2-adrenergic agonists cause no or minimal respiratory depression.29,30 None of our patients had respiratory depression during the operation or in the recovery room.

In conclusion, dexmedetomidine infusion in the perioperative period significantly reduced the shivering associated with spinal anesthesia during minor surgical procedures without any major adverse effects. We therefore conclude that dexmedetomidine infusion as a good choice for preventing shivering in patients undergoing spinal anesthesia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crowley LJ, Buggy DJ. Shivering and neuraxial anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33:241–52. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glosten B, Sessler DI, Faure EA, Karl L, Thisted RA. Central temperature changes are poorly perceived during epidural anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:10–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199207000-00003. 10.1097/00000542-199207000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozaki M, Kurz A, Sessler DI, Lenhardt R, Schroeder M, Moayeri A, Noyes KM, Rotheneder E. Thermoregulatory thresholds during epidural and spinal anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1994;8:282–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199408000-00004. 10.1097/00000542-199408000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai YC, Chu KS. A comparison of tramadol, amitriptyline, and meperidine for postepidural anesthetic shivering in parturients. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:1288–92. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200111000-00052. 10.1097/00000539-200111000-00052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macintyre PE, Pavlin EG, Dwersteg JF. Effect of meperidine on oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, and respiratory gas exchange in postanesthesia shivering. Anesth Analg. 1987;66:751. 10.1213/00000539-198708000-00010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doze VA, Chen BX, Maze M. Dexmedetomidine produces a hypnotic-anesthetic action in rats via activation of central alpha-2 adrenoceptors. Anesthesiology. 1989;71:75–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198907000-00014. 10.1097/00000542-198907000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Virtanen R, Savola JM, Saano V, Nyman L. Characterization of the selectivity, specificity and potency of medetomidine as an alpha-2 adrenoceptor agonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;150:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90744-3. 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90744-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elvan EG, Oç B, Uzun S, Karabulut E, Coşkun F, Aypar U. Dexmedetomidine and postoperative shivering in patients undergoing elective abdominal hysterectomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008;255:357–64. doi: 10.1017/S0265021507003110. 10.1017/S0265021507003110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blaine Easley R, Brady KM, Tobias JD. Dexmedetomidine for the treatment of postanesthesia shivering in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2007;174:341–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2006.02100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson E, David A, MacKenzie N, Grant IS. Sedation during spinal anaesthesia: comparison of propofol and midazolam. Br J Anaesth. 1990;64:48–52. doi: 10.1093/bja/64.1.48. 10.1093/bja/64.1.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsukawa T, Sessler DI, Sessler AM, Schroeder M, Ozaki M, Kurz A, Cheng C. Heat flow and distribution during induction of general anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:662–73. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199503000-00008. 10.1097/00000542-199503000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurz A, Sessler I, Schroeder M, Kurz M. Thermoregulatory response thresholds during spinal anaesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1993;77:721–6. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199310000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buggy DJ, Crossley AW. Thermoregulation, mild perioperative hypothermia and postanaesthetic shivering. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:615–28. doi: 10.1093/bja/84.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witte JD, Sesler DI. Perioperative shivering. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:467–84. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200202000-00036. 10.1097/00000542-200202000-00036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwarzkopf KR, Hoff H, Hartmann M, Fritz HG. A comparison between meperidine, clodine and urapidil in the treatment of postanesthetic shivering. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:257–60. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200101000-00051. 10.1097/00000539-200101000-00051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenhardt R, Orhan-Sungur M, Komatsu R, Govinda R, Kasuya Y, Sessler DI, et al. Suppression of shivering during hypothermia using a novel drug combination in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:110–5. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181a979a3. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181a979a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alfonsi P, Passard A, Gaude-Joindreau V, Guignard B, Sessler DI, Chauvin M. Nefopam and alfentanil additively reduce the shivering threshold in humans whereas nefopam and clonidine do not. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:102–9. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181a979c1. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181a979c1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel D, Janardhan Y, Merai B, Robalino J, Shevde K. Comparison of intrathecal meperidine and lidocaine in endoscopic urological procedures. Can J Anaesth. 1990;37:567–70. doi: 10.1007/BF03006327. 10.1007/BF03006327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sagir O, Gulhas N, Toprak H, Yucel A, Begec Z, Ersoy O. Control of shivering during regional anaesthesia: prophylactic ketamine and granisetron. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51:44–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01196.x. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01196.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doufas AG, Lin CM, Suleman MI, Liem EB, Lenhardt R, Morioka N, et al. Dexmedetomidine and meperidine additively reduce the shivering threshold in humans. Stroke. 2003;34:1218–23. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000068787.76670.A4. 10.1161/01.STR.0000068787.76670.A4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bicer C, Esmaoglu A, Akin A, Boyaci A. Dexmedetomidine and meperidine prevent postanaesthetic shivering. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2006;232:149–53. doi: 10.1017/S0265021505002061. 10.1017/S0265021505002061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talke P, Tayefeh F, Sessler DI, Jeffrey R, Noursalehi M, Richardson C. Dexmedetomidine does not alter the sweating threshold, but comparably and linearly decreases the vasoconstriction and shivering thresholds. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:835–41. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00017. 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frank SM, Higgins MS, Breslow MJ, Fleisher LA, Gorman RB, Sitzmann JV, et al. The catecholamine,cortisol, and hemodynamic responses to mild perioperative hypothermia. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:83–93. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199501000-00012. 10.1097/00000542-199501000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurz A, Sessler DI, Narzt E, Bekar A, Lenhardt R, Huemer G. Postoperative hemodynamic and thermoregulatory consequences of intraoperative core hypothermia. J Clin Anesth. 1995;7:359–66. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(95)00028-g. 10.1016/0952-8180(95)00028-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erkola O, Korttila K, Aho M, Haasio J, Aantaa R, Kallio A. Comparison of intramuscular dexmedetomidine and midazolam premedication for elective abdominal hysterectomy. Anesth Analg. 1994;79:646–53. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199410000-00006. 10.1213/00000539-199410000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coskuner I, Tekin M, Kati I, Yagmur C, Elcicek K. Effects of dexmedetomidine on the duration of anaesthesia and wakefulness in bupivacaine epidural block. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2007;24:535–40. doi: 10.1017/S0265021506002237. 10.1017/S0265021506002237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jalonen J, Hynynen M, Kuitunen A, Heikkilä H, Perttilä J, Salmenperä M, et al. Dexmederomidine as an anesthetic adjunct in coronary artery bypass grafting. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:331–45. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199702000-00009. 10.1097/00000542-199702000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebert TJ, Hall JE, Barney JA. The effects of increasing plasma concentrations of Dexmedetomidine in humans. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:382–94. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200008000-00016. 10.1097/00000542-200008000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaakola ML. Dexmedetomidine premedication before intravenous regional anesthesia in minor outpatient hand surgery. J Clin Anesth. 1994;6:204–11. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(94)90060-4. 10.1016/0952-8180(94)90060-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carollo DS, Nossaman BD, Ramadhyani U. Dexmedetomidine: a review of clinical applications. Anesthesiology. 2008;21:457–61. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328305e3ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]