Abstract

Allograft and bioabsorbable screw use in ACL revision surgery is common. However, both allograft and bioabsorbable screws have been associated with immunological reactions that lead to tunnel enlargement. Long term studies examining tibial tunnel enlargement in this population are currently not available. We report a case of severe tibial and femoral tunnel enlargement 6.5 years after anterior cruciate ligament revision surgery with anterior tibialis and semitendinosus allograft and bioabsorbable screw fixation. Longitudinal knee arthrometer data, knee exam under anesthesia and arthroscopic inspection of the graft demonstrated minimal effects of severe tunnel enlargement on anterior knee laxity and graft integrity. To our knowledge this is the first case report of a longitudinal assessment of anterior knee laxity associated with severe tunnel enlargement. Surgeons should be aware of this condition and the clinical consequences that may accompany bone tunnel enlargement after ACL surgery.

Keywords: Tunnel enlargement, Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

Introduction

Although bone tunnel enlargement after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction is well documented, the clinical consequences and relationship to ACL integrity remain controversial.1,2 Regardless of its effects on the ACL reconstruction, tunnel enlargement complicates revision procedures, may increase stress risers in the tibia and could ultimately lead to tibial fracture.3,4 The etiology of bone tunnel enlargement is not well understood; however, both mechanical (bone resorption due to stress shielding and motion in the tunnel) and biological factors (immune response to allograft or bioabsorbable materials, cytokine/inflammatory response) likely contribute to the process.1 Although anterior knee laxity appears unaffected by tibial tunnel enlargement in the short term, the long-term relationship with knee laxity and increased failure is unknown. We report a case of severe tibial and femoral tunnel enlargement followed with serial laxity assessments for 6.5 years after ACL surgery. To our knowledge this is the first case report of a longitudinal assessment of anterior knee laxity associated with severe tunnel enlargement.

Case Report

A 30-year-old female presented with recent exacerbation of left knee pain and swelling. Her past surgical history on the injured knee included previous ACL, MCL, lateral and medial meniscus injuries in 1998 (12 years, 2 months from current presentation), that were treated with ACL reconstruction using a bone-tendon-bone autograft and meniscal repairs. The patient underwent multiple secondary procedures due to continued pain and instability (Figure 1). Six and a half years after the primary ACL reconstruction an ACL revision was performed using anterior tibialis-semitendinosus tendon allografts. Eleven mm tibial tunnel and femoral sockets were drilled. Femoral fixation was with an endobutton and tibial fixation used a 10×25 Bio RCI screw with a soft tissue staple. Two years after ACL revision, the patient experienced anteromedial proximal tibial pain. A small fluid collection was noted at the tibial tunnel site. The tibial staple was removed at this time. Six weeks after tibial hardware removal, the patient experienced a large sterile cyst at the tibial tunnel. Despite traumatic rupture of the cyst and multiple aspirations, the patient continued to have recurring anteromedial tibial pain near the tibial tunnel site. At the time of her current presentation (6.5 years since ACL revision), an MRI demonstrated tunnel synovitis (Figure 2A) with severe widening of the tibial tunnel (3.67 cm2 area, 303% increase) and moderate to severe widening of the femoral tunnel (2.6 cm2 area, 221% increase). There was no apparent osteo-integration of the graft in the tibial and femoral tunnels.

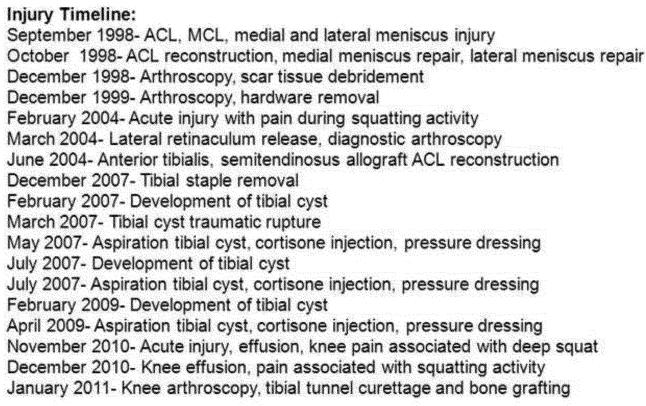

Figure 1. Injury and Treatment History.

History of injuries ad procedural treatments for a 30 year old female presenting with acute left knee effusion and pain.

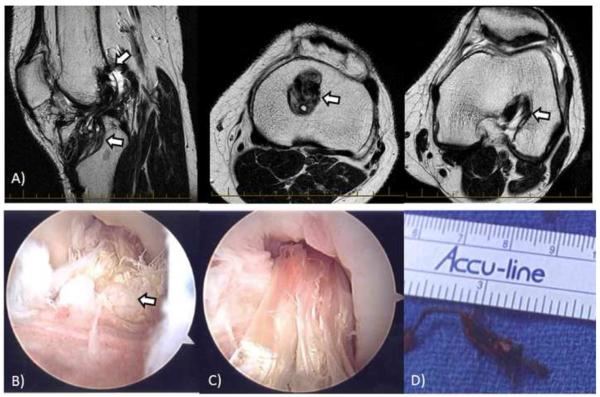

Figure 2. Imaging and Arthroscopy Pictures.

Images and arthroscopy pictures of the left knee of a 30 year old female patient 6.5 years after ACL revision reconstruction with allograft and bioabsorbable screw fixation. Patient was placed in supine position on standard operating table. A) Magnet resonance imaging of the tibial and femoral tunnels, arrows indicate tunnel enlargement. B) Arthroscopy pictures from anteromedial portal view of fraying of ACL at tibial insertion and C) intact graft. D) Suture removed from tibial tunnel.

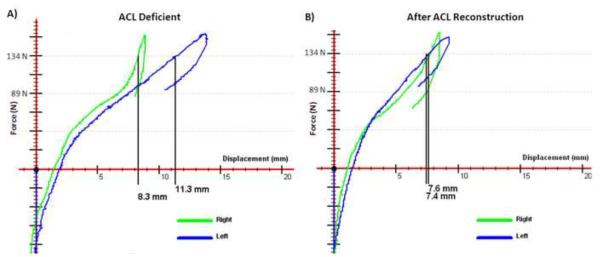

Longitudinal anterior knee laxity data was available starting prior to the patient's ACL revision (ACL deficient state) until 1 month prior to arthroscopic evaluation (6.5 years after ACL revision). The knee arthrometer data was collected on a CompuKT Knee Ligament Arthrometer (MEDmetric Corp, San Deigo, CA) by the same licensed physical therapist (Intra-rater reliability: ICC=0.92). Prior to the ACL revision, comparison to the uninjured contralateral limb demonstrated > 3 mm increase in anterior displacement at 134 N of anterior force which indicated ACL deficiency (Table 1, Figure 3).5,6 After ACL revision, the patient's side-to-side difference in anterior knee displacement was ≤ 2 mm for all testing dates (Table 1, Figure 3).

Table 1. Anterior Knee Laxity Data.

Longitudinal anterior knee laxity of a 30 year old female status post primary ACL reconstruction (12 years prior to current presentation) and post ACL revision with allograft and bioabsorbable screw fixation (6.5 years prior to current presentation). The knee arthrometer data was collected on a CompuKT Knee Ligament Arthrometer by the same licensed physical therapist (Intra-rater reliability: ICC=0.92D. The data was analyzed at 134 N of anterior tibial force for side-to-side differences between the involved and uninvolved. The first date represents an ACL deficient state that was confirmed by arthroscopy. January 2011 data was collected after arthroscopic debridement and tibial tunnel bone grafting.

| Date | Side-to-Side Difference in Anterior Displacement (mm) |

|---|---|

| June 2004 | 3.2* |

| August 2004 | 0.4 |

| July 2005 | 0.4 |

| June 2009 | 2.0 |

| December 2010 | 0.3 |

| January 2011 | 0.3 |

Greater than 3 mm difference in side-to-side comparison of anterior tibial displacement.

Figure 3. KT-2000 knee arthrometer laxity curves.

Longitudinal anterior knee laxity of a 30 year old female status post primary ACL reconstruction (12 years prior to current presentation) and post ACL revision with allograft and bioabsorbable screw fixation (6.5 years prior to current presentation). The knee arthrometer data was collected on a CompuKT Knee Ligament Arthrometer by the same licensed physical therapist (Intra-rater reliability: ICC=0.92D. A) ACL deficient case (left knee) compared to right knee. B) Six and half years after ACL reconstruction (left knee) compared to right knee. ACL deficiency was indicated prior to revision due to >3mm difference in anterior knee laxity between involved and uninvolved limb. After ACL revision, the patient's side-to-side difference in anterior knee displacement was ≤ 2 mm.

Six and a half years after the revision ACL surgery, open tibial tunnel curettage with bone grafting and knee arthroscopy was performed to evaluate graft integrity. Exam under anesthesia demonstrated stable anterior and posterior drawer tests, negative Lachman's and normal pivot shift tests with a firm endpoint. Arthroscopic exam revealed a small, chronic, partial ACL tear involving <1/3 of the graft. The tibial tunnel was explored and debrided in a retrograde fashion through an open incision. Fibrotic tissue and sclerotic bone around the site was debrided including sutures from previous ACL reconstruction (Figure 2D). The defect was then packed with allograft cancellous bone. Knee arthrometer data was also performed 3 weeks after arthroscopic debridement and tibial bone grafting (Table 1).

Discussion

Bone tunnel enlargement or tunnel lysis is common after ACL reconstruction, irrespective of the graft type and fixation.1,7,8 While anterior knee laxity appears unaffected by tibial tunnel enlargement in the short term, the long-term relationship of tunnel enlargement with knee laxity and increased ACL failure is unknown.1 This report demonstrates a case of severe tunnel enlargement after ACL revision with allograft and bioabsorbable screw fixation. The patient experienced pain and tibial tunnel sterile cysts associated with the tunnel synovitis and enlargement over 6 years after the ACL revision. Knee arthrometer data demonstrated side-to-side differences between injured and unaffected limb of less than 3 mm, which is consistent with ACL intact conditions.6 Thus, despite substantial tunnel enlargement 6 years after ACL revision, the anterior knee laxity and graft integrity appeared unaffected by the increased bone tunnel sizes.

Although the long term anterior knee laxity appears unaffected by significantly enlarged bone tunnels, other clinical consequences should be considered for treatment guidance. The risk of stress reactions, tibial plateau fracture, tibial tunnel associated cysts, and complicating subsequent ACL surgery remain concerns. Bone grafting should be considered in patients that have severe tunnel enlargement regardless of anterior knee laxity or graft integrity.9-11 Due to the patient's symptoms of chronic tibia pain and tibial cyst formation, bone graft was placed in the tibial tunnel to prevent future stress fracture, cyst formation and pain.

Several reports of severe bone tunnel enlargement and pre-tibial cyst formation after ACL reconstruction are found in the literature; however, few studies examining their long term sequelae exist. ACL revisions are often performed using allograft tissue and bioabsorbable screws. Both allograft and bioabsorbable screws have been associated with immunological reactions that lead to tunnel enlargement.1 Though the presentation of this patient may be rare, allograft and bioabsorbable screw use in ACL revision surgery is common and long term studies examining tibial tunnel enlargement in this population are currently not available. Surgeons should be aware of this condition and the clinical consequences that may accompany bone tunnel enlargement after ACL surgery.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Work performed at Cincinnati Children's Hospital and The Ohio State University.

References

- 1.Wilson TC, Kantaras A, Atay A, Johnson DL. Tunnel enlargement after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:543–9. doi: 10.1177/0363546504263151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hogervorst T, van der Hart CP, Pels Rijcken TH, Taconis WK. Abnormal bone scans of the tibial tunnel 2 years after patella ligament anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: correlation with tunnel enlargement and tibial graft length. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:322–8. doi: 10.1007/s001670000165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson AW, Smith JJ. Proximal tibial fracture after patellar tendon autograft for ipsilateral ACL reconstruction. J Knee Surg. 2009;22:142–4. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mithofer K, Gill TJ, Vrahas MS. Tibial plateau fracture following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12:325–8. doi: 10.1007/s00167-003-0445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rangger C, Daniel DM, Stone ML, Kaufman K. Diagnosis of an ACL disruption with KT-1000 arthrometer measurements. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1993;1:60–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01552161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniel DM, Stone ML, Sachs R, Malcom L. Instrumented measurement of anterior knee laxity in patients with acute anterior cruciate ligament disruption. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13:401–7. doi: 10.1177/036354658501300607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.L'Insalata JC, Klatt B, Fu FH, Harner CD. Tunnel expansion following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a comparison of hamstring and patellar tendon autografts. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1997;5:234–8. doi: 10.1007/s001670050056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stener S, Ejerhed L, Sernert N, Laxdal G, Rostgard-Christensen L, Kartus J. A long-term, prospective, randomized study comparing biodegradable and metal interference screws in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: radiographic results and clinical outcome. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1598–605. doi: 10.1177/0363546510361952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thaunat M, Chambat P. Pretibial ganglion-like cyst formation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a consequence of the incomplete bony integration of the graft? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:522–4. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thaunat M, Nourissat G, Gaudin P, Beaufils P. Tibial plateau fracture after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Role of the interference screw resorption in the stress riser effect. Knee. 2006;13:241–3. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simonian PT, Wickiewicz TL, O'Brien SJ, Dines JS, Schatz JA, Warren RF. Pretibial cyst formation after anterior cruciate ligament surgery with soft tissue autografts. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:215–20. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(98)70044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]