Abstract

Purpose

This paper highlights a descriptive study of the challenges and lessons learned in the recruitment of rural primary care physicians into a randomized clinical trial using an Internet-based approach.

Methods

A multidisciplinary/multi-institutional research team used a multilayered recruitment approach, including generalized mailings and personalized strategies such as personal office visits, letters, and faxes to specific contacts. Continuous assessment of recruitment strategies was used throughout study in order to readjust strategies that were not successful.

Results

We recruited 205 primary care physicians from 11 states. The 205 lead physicians who enrolled in the study were randomized, and the overall recruitment yield was 1.8% (205/11 231). In addition, 8 physicians from the same practices participated and 12 nonphysicians participated. The earlier participants logged on to the study Web site, the greater yield of participation. Most of the study participants had logged on within 10 weeks of the study.

Conclusion

Despite successful recruitment, the 2 major challenges in recruitment in this study included defining a standardized definition of rurality and the high cost of chart abstractions. Because many of the patients of study recruits were African American, the potential implications of this study on the field of health disparities in diabetes are important.

Keywords: recruitment, physicians, diabetes, Internet intervention

INTRODUCTION

Limited primary care services in rural areas translate to limited access to health care services, health insurance, or specialty care,1 all of which are manifested by poorer health status2 and greater health disparities among rural residents.1 These issues, in combination with the rapidly increasing incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the southern United States, particularly among African Americans,3–5 highlight the need for studies that evaluate the practice patterns and challenges of physicians who treat diabetics in the rural south, where there are high African American populations.

Rural physicians often practice in isolated settings, which can impede their access to continuing education opportunities that provide clinical updates and guidance.6 Educational interventions delivered via the Internet have been shown to be effective7 and provide a flexible, convenient, and highly accessible mode for continuing education offerings, particularly in rural settings. Similar technology is now widely employed to engage community practitioners in research. However, recruitment of physicians for office-based research can be challenging and includes barriers such as concern about office disruption, respondent burden, fear of evaluation, and lack of experience and investment in research.8

A few studies have begun to focus on the mechanics of how to successfully recruit physicians into clinical research.9–11 These studies cite use of friendship networks and physicians recruiting physicians as critical factors in success of recruiting physicians into clinical studies. Several studies have also reviewed recruitment of physicians into Internet-based approaches;12–14 however, very few have focused on recruitment of physicians practicing in rural areas, particularly those practicing in the south.

Identifying strategies to successfully recruit physicians in rural areas is desirable. The Rural Diabetes Online Care (RDOC) Project was developed to evaluate the effectiveness of a multifaceted, professional development Internet-based intervention for rural primary care physicians.15–18 This paper summarizes the methods employed in the recruitment of rural physicians into the RDOC study and gives an in-depth descriptive analysis of the recruitment process, particularly as it relates to physicians practicing in rural areas predominately in the southern United States.

METHODS

Overall Recruitment Plan

Before the study began, institutional review board approval was obtained at The University of Alabama medical campus in both Tuscaloosa and Birmingham. Consent was received after successful login of participants. The general recruitment plan was based on several factors. First, we obtained extensive input in the design and implementation of the study from rural Alabama physicians through surveys, focus groups, in-depth interviews, and pilot testing. This approach allowed us to obtain more buy-in, overcome access barriers, and refine and customize the intervention. Second, we capitalized upon ongoing, long-term and long-standing relationships believed to have good credibility and reputation through the Alabama Practice-Based Research Network (APBRN) of 359 primary care physicians, The University of Alabama Family Medicine Residency Program alumni, and faculty and leadership at The University of Alabama Family Residency Program. The University of Alabama Family Medicine Residency Program is located in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, as one of the branch campuses of The University of Alabama School of Medicine in Birmingham, Alabama. Third, we emphasized incentives gained from the study, including continuing medical education (CME) and continuing education units (CEUs) for office staff, personalized performance feedback in real time with an objective, data-driven benchmark and peer performance comparisons, and financial incentives.

We initially found that providing on-the-job training and certification via Internet was desirable, as many office staff had limited time available for the CEU certification process. Finally, we built upon the research team’s previous research experience with rural physician practices involving quality improvement/guideline adherence. For example, because many of the research team members had already conducted outcomes research with rural physicians, this experience was leveraged in the planning and implementation of this study.

Recruitment was facilitated through mailings, faxes, telephone calls, presentations/recruitment at professional meetings, and on-site visits. We found it helpful to succinctly outline the benefits of participating in the study. During the recruitment phase, having a frequently asked questions (FAQ) sheet facilitated the transmission of information. The overall recruitment period lasted slightly more than 1 year. A summary of the study’s recruitment efforts and the time devoted to each is provided (Box).

Box. Rural Diabetes Online Care Recruitment Timeline.

| Date | Activity |

|---|---|

| Prerecruitment/prelaunch | |

| February 2006 |

|

| July-August 2006 |

|

| (Summer 2006) |

|

| September-November 2006 |

|

| September-December 2006 |

|

| January 2007 |

|

| February 2007 |

|

| January-February 2007 |

|

| March-May 2007 |

|

| April 2007 |

|

| June-August 2007 |

|

| June 2008 |

|

Description of Intervention and Control Groups

The RDOC study was a randomized, controlled study of 205 rural physician offices to an intervention or comparison group in an 18-month online intervention. The intervention consisted of interactive learning modules that provided case-based education, performance feedback measures, and benchmarks as a model for improving physician adherence to guidelines for diabetes management. To enroll, a primary care physician had to access the study Internet site and review the online consent material.

Randomization occurred online immediately after consent. The first physician from an office to enroll was designated as the lead physician. Subsequent physicians or office personnel participating in the study were assigned to the same study arm as the lead physician. The intervention Web site, which was developed with input from rural primary physicians, contained (1) tips and tools to help practitioners save time during the office visit, (2) a summary of diabetes control guidelines and goals, (3) case-based continuing education, and (4) patient education materials.

Lead physicians received feedback about areas for practice improvement based on medical record review. Those in the intervention group also received feedback from interactive case vignettes that allowed them to compare their performance with that of their peers. The control Web site contained traditional test-based CME and links to national diabetes resources. Participants were eligible to receive CME credit for completing sections from the Web site. The main outcomes of the study were control of diabetes process of care measures (A1C control, lipid control, blood pressure control, medication intensification). Data were obtained covering physician practice patterns by chart abstraction.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria for Study

The study targeted family medicine, internal medicine, and general practice physicians. Additionally, the inclusion criteria were based on the rurality of practice definitions. There are several different taxonomies for “rurality” that vary based on criteria such as population size, density, proximity or degree of urbanization, adjacency and relationship to a metropolitan area, principal economic activity, economic and trade relationships, and work commutes.19 We used a combination of rural definitions in different phases of the study in order to increase the potential recruitment area in a standardized way. We initially targeted rural physician practices located in 7 southeastern states: Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, Tennessee, Florida, Arkansas, and Kentucky (wave 1). Our aim was to recruit practices within a 400-mile area of the study’s main site in Birmingham to more easily facilitate on-site chart abstraction if necessary.

A subsequent modification of the inclusion criteria resulted in a second recruitment, which included some deletion as well as addition of counties to wave 1 counties and the addition of 4 states and their rural counties: North Carolina, South Carolina, West Virginia, and Missouri (wave 2). These modifications were conducted in order to better standardize our rural definition as well as to add to the recruitment pool. The 4 states selected in wave 2 included southern as well nonsouthern counties that contained rural populations which we felt were compatible in a variety of ways with our wave 1 populations (ie, population size, geographic distribution, ethnic/racial composition, socioeconomic composition, and cultural factors; see Table 1 for a summary of criteria used to define rurality in recruitment of physicians and the states that were targeted for recruitment).

Table 1.

Summary of Rural Definitions Used for Recruitment

| Phase (Start Date) | Rurality Definition for Counties |

Targeted States | Target No. of Physicians |

N Recruited (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 (September 2006) |

City with a population of ≥50 000 inhabitants (FIPS designation = 3). |

AL, MS, GA, FL, TN, AR, KY |

2231 | 151 (73.7%) |

| Wave 2 (June 2007) |

City with a population of ≥25 000 (FIPS designation = 5). |

AL, MS, GA, FL, TN, AR, NC, SC, WV, MO |

9000 | 54 (26.3%) |

| Total | 11231 | 205 (100%) |

Abbreviation: FIPS, federal information processing standard of 3 = 3 digit code unique for that state.

Physician recruitment lists were obtained from 4 sources: (1) Phoenix ESI International Co, a marketing and data management company utilized by the American Medical Association; (2) state licensure data; (3) the alumni database of the Tuscaloosa Family Medicine Residency Program at The University of Alabama School of Medicine, Tuscaloosa Campus; and (4) the alumni database of the Tuscaloosa Family Medicine Residency Program; and (4) the APBRN.

Measures

This study was designed to be descriptive in nature, so no hypotheses were formulated. During the recruitment period, we recorded the number of lead physicians and other health care providers participating in the study, location of practice, registration date, number of registration failures, number of successful registrations, number of withdrawals from study, and frequency of logins. We also used standard descriptive statistics and SPSS software 16.0 for analysis and Excel software for plotting graphs (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington).

RESULTS FROM RECRUITMENT

Rural primary care physicians practicing in 11 states participated. The 205 lead physicians who enrolled in the study were randomized and the overall recruitment yield was 1.8% (205/11 231). In addition, 8 physicians from the same practices participated and 12 nonphysicians participated.

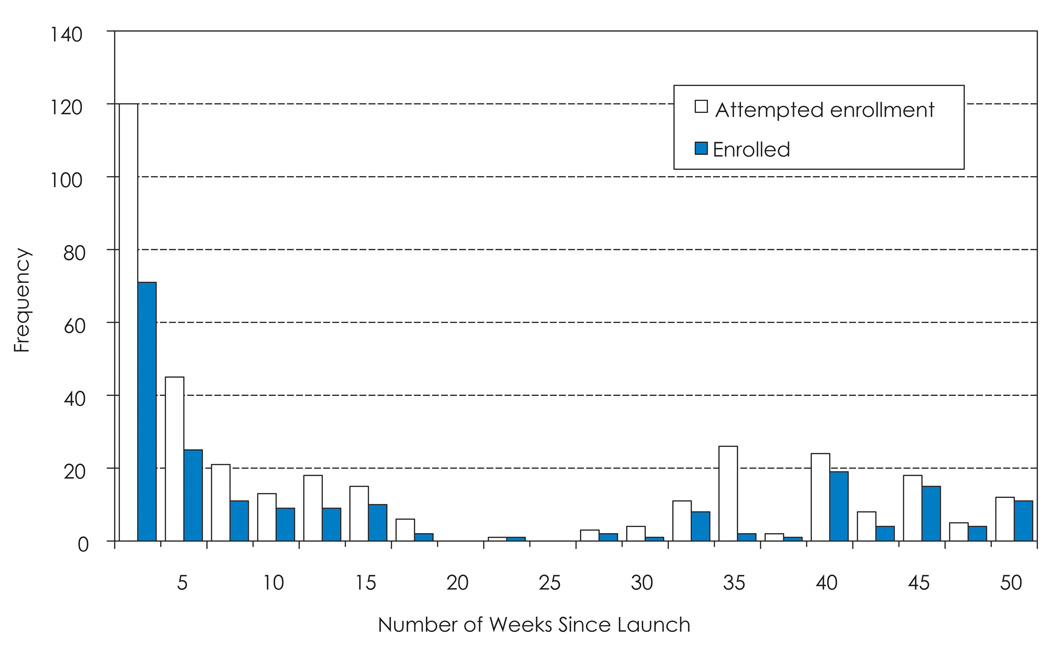

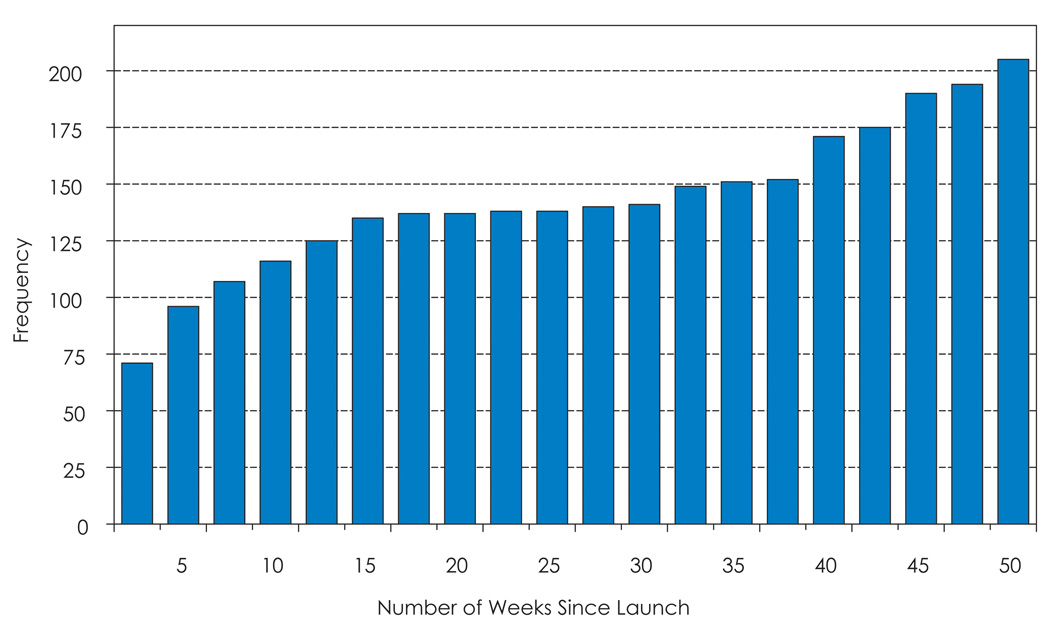

Most of the successful registrations for the study occurred during the first 10 weeks of the study (Figure 1). Importantly, 60.3% of those who logged on enrolled. The reasons for failure to enroll varied: (1) the user closed the browser, (2) no entry was entered which allowed an empty field, (3) a non-MD tried first or no job title was entered by the user, (4) the participant did not consent, or (5) the geographical county entered was ineligible for the rural definition of study. Enrollment after week 10 declined steadily. However, enrollment after week 30 increased due to efforts from the wave 2 recruitment imitative. The cumulative number of physicians enrolled (Figure 2) demonstrating an inflection in the curve at week 40.

Figure 1.

Frequency of Physicians Attempting Enrollments and Enrolled

Figure 2.

Cumulative Number of Physicians Enrolled (n = 205)

Study participation rates were highest in Alabama (29.8%), followed by Mississippi (12.4%), Georgia (11.2%), and Kentucky and North Carolina (both at 10.7%). Most participants had Internet access within their practices (95.7%). The intervention group logged onto the site an average of 5.2 times (SD = 1.3), compared to the control group at 1.8 times (SD = 1.3). Sixty-five (29%) participants withdrew from the study at baseline. Reasons for withdrawal included (1) the physician was too overwhelmed or busy to participate, (2) the physician was retired or was leaving the practice, (3) it was too time-consuming to copy the charts, (4) the physician was hesitant because of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, and (5) the physician was no longer interested in participating.

Most participants preferred to mail their records to the research team compared to receiving in-house chart abstractions (47.3%), while approximately 25.4% of participants did not indicate their preference for medical record abstraction.

DISCUSSION

Although we were able to successfully recruit our target number, there were several challenges encountered that may be unique to recruitment of this special population. Although previous studies suggested that personalized strategies work best,9–11 our ability to recruit in a face-to-face or direct manner was hampered by our large geographical target area. Therefore, we used a multilayered/multiteam approach to recruitment.

We used targeted and personalized mailings and e-mails, faxes, a small number of office visits, and recruitment at meetings to meet our recruitment goal. The recruitment team was large and consisted of members from multiple academic institutions and various backgrounds. We also relied on the assistance of people currently in practice and in contact with rural physicians to plan and implement this project. In addition, the team members each had different tasks assigned to them with frequent collaborative meetings to follow-up and troubleshoot during the project. This multilayered and multiteam approach, along with clear timelines, consistent follow-up, and clear outcomes contributed greatly to the success of recruitment of rural physicians and health care providers into this study.

Our highest yield for recruitment came from the use of large physician lists with mailings, which contradicts previous studies where direct recruitment to clinical studies occurred through either friendship or nonfriendship physician networks. However, although personalized strategies such as the use of personalized letters to alumni or use of physician research networks did not yield high recruitment, it is believed that such strategies may be important for recruitment in future studies. The timeliness of recruitment has also been an important issue in the successful recruitment of physicians for Internet-based interventions. Typically, the earlier the physician completes the intervention, the better the completion success rate. Additionally, the timing of the intervention around holidays, vacation time, or other recruitment events plays an important role in this process.20,21 We found this to be true in this study, where the number of successful registrations were often clustered around recruitment activities.

Perhaps one of our challenges that is not unique to this study was how to define “rurality” of our potential recruitees. This challenge has been cited in the literature often.16 This study used a process of refinement of original definitions to eventually get one that was practical and standardized (Table 1 for summary of definition). Research that continues to standardize this definition is essential in order to conduct research of this type. Therefore, determining a consistent definition of rurality should be high priority in order to move diabetes management and health disparities research forward.

Ways to balance the costs of the study must also be considered. We initially kept the location of recruitment close to our main research site, Birmingham, Alabama, in order to limit the travel needed to conduct on-site visits for chart abstraction from study personnel. However, due to limited recruitment from the 7 initial states used for the study, we had to expand our recruitment area. One way to avoid costly travel time to conduct face-to-face chart abstractions to far away locations was to have chart abstractions mailed, which we did for several long-distance recruits.

Another challenge for this study and others that recruit rural physicians was the heavy patient load of rural physicians.22 To complete the study, physician practices had to agree to chart abstractions, a time-intensive and burdensome process to an already busy practice. To counter this challenge, we had to carefully consider the incentives we offered for participation, as well as make adjustments as needed. Incentives to both recruit physicians into the study as well as retain them in the study during a 2-year period included providing CMEs, CEUs, compensation for time invested, as well as holiday thank you cards.

Lastly, we also emphasized the great value that study participants would have in adding to scientific knowledge in this field. We are currently conducting a follow-up survey to assess the particular reasons why rural physicians participate in this type of research. It is important to note that 7 of our targeted states for recruitment rank in the top 10 states with the highest prevalence of diabetes in the United States.3,4

Many of our targeted states also have large proportions of African Americans suffering from health disparities. The ethnicity/race of the physicians gives some clues about the concordance rates between practitioner and patients who can influence overall health outcomes and, in this case, diabetes outcomes. The race of rural physicians would be helpful in attempting to see an effect on these outcomes and could also give clues about where to tailor interventions and recruitment efforts around diabetes management and outcomes. Although we did not collect this information at the onset of the study, we are now in the process of collecting and analyzing this data. Other factors that contribute to disparities in diabetes include care-seeking behaviors, access to ambulatory care rather than reliance on the emergency department, and emphasis on health promotion.23–26 These factors should be studied in more detail in rural settings.

This study is unique from others that have closely examined physician recruitment into Internet-based studies because very few studies have documented recruitment of a rural physician population. This paper adds to the limited knowledge of how to maximize the approach. This could be important in health disparities research, where large minority populations such as African Americans live in concentrated areas of the south and where these populations currently comprise the bulk of disparities in diseases such as diabetes. Research that better understands the practice management skills and competencies of physicians who serve this population could provide some of the answers for solving health disparities.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases X050111012 and R18 DK065001-01AZ (Drs Allison and Safford), and Clinical Trials registration NCT00403091, Internet Intervention to Improve Rural Diabetes Care (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/).

REFERENCES

- 1.O’Brien T, Denham SA. Diabetes care and education in rural regions. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34:334–347. doi: 10.1177/0145721708316318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloom DE, Canning D, Jamison DT. Health, wealth, and welfare. Finance Development. 2004;31:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Number of people with diabetes increases to 24 million: estimates of diagnosed diabetes now available for all US counties [press release] Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [Accessed November 13, 2008]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Fact Sheet. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; General information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dabney B, Grosschalk A. Diabetes in rural areas: a literature review. In: Gamm LD, Hutchison LL, Dabney BJ, Dorsey AM, editors. Rural Healthy People 2010: A Companion Document to Healthy People 2010. Vol. 2. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University System Health Science Center; 2003. pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hart LG, Salsberg E, Phillips DM, Lishner DM. Rural health care providers in the United States. J Rural Health. 2002;18 suppl:211–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2002.tb00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook RF, Billings DW, Hersch RK, Back AS, Hendrickson A. A field test of a web-based workplace health promotion program to improve dietary practices, reduce stress, and increase physical activity: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9:e17. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.2.e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levinson W, Dull VT, Roter DL, Chaumeton N, Frankel RM. Recruiting physicians for office-based research. Med Care. 1998;36:934–937. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199806000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borgiel AEM, Dunn EV, Lamont CT, et al. Recruiting family physicians as participants in research. Fam Pract. 1989;6:168–172. doi: 10.1093/fampra/6.3.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carey TS, Kinsinger L, Keyserling T, Harris R. Research in the community: recruiting and retaining practices. J Community Health. 1996;21:315–327. doi: 10.1007/BF01702785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asch S, Conner SE, Hamilton EG, Fox SA. Problems in recruiting community-based physicians for health services research. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:591–599. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis SD, Bertoni AG, Bonds DE, et al. Value of recruitment strategies used in a primary care practice-based trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:258–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glasgow RE, Boles SM, McKay HG, Feil EG, Barrera M., Jr. The D-Net diabetes self-management program: long-term implementation, outcomes, and generalization results. Prev Med. 2003;36:410–419. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodyear-Smith F, York D, Petousis-Harris H, et al. Recruitment of practices in primary care research: the long and the short of it. Fam Pract. 2009;26:128–136. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmp015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Safford MM, Salanitro A, Houston TK, et al. How much physician is there to profile? Patient complexity and quality of care measurement. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23 suppl 2:318. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salanitro A, Estrada CA, Safford MM, et al. Using patient complexity to inform physician profiles in the pay-for-performance era. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24 suppl 1:S211–S212. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salanitro A, Safford MM, Houston TK, et al. Is patient complexity associated with physician performance on diabetes measures? J Gen Intern Med. 2009;23 suppl 2:335. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salanitro AH, Estrada CA, Allison JJ. Implementation research: beyond the traditional randomized controlled trial. In: Glasser SP, editor. Essentials of Clinical Research. Springer; 2008. pp. 217–244. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hart LG, Larson EH, Lishner DM. Rural definitions for health policy and research. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1149–1155. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdolrasulnia M, Collins BC, Casebeer L, et al. Using email reminders to engage physicians in an Internet-based CME intervention. BMC Med Educ. 2004;4:17. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Im EO, Chee W. Recruitment of research participants through the Internet. Comput Inform Nurs. 2004;22:289–297. doi: 10.1097/00024665-200409000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowman RC, Crabtree BF, Petzel JB, Hadley TS. Meeting the challenges of workload and building a practice: the perspectives of 10 rural physicians. J Rural Health. 1997;13:71–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1997.tb00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper LA, Hill MN, Powe NR. Designing and evaluating interventions to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:477–486. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hewins-Maroney B, Schumaker A, Williams E. Health seeking behaviors of African Americans: implications for health administration. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2005;28:68–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill-Briggs F, Gary TL, Bone LR, Hill MN, Levine DM, Brancati FL. Medication adherence and diabetes control in urban African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Health Psychol. 2005;24:349–357. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen JJ, Washington EL. Identification of diabetic complications among minority populations. Ethn Dis. 2008;18:136–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]