Abstract

The principal objective of our research is to examine whether the earned income tax credit (EITC), a broad-based income support program that has been shown to increase employment and income among poor working families, also improves their health and access to care. A finding that the EITC has a positive impact on the health of the American public may help guide deliberations about its future at the federal, state, and local levels. The authors contend that a better understanding of the relationship between major socioeconomic policies such as the EITC and the public’s health will inform the fields of health and social policy in the pursuit of improving population health.

Keywords: social determinants, health policy, population health

Introduction

Low socioeconomic status, measured variously in terms of poverty, income, wealth, education or occupation, has been repeatedly linked to a great burden of disease and death in the United States.1–5 However, researchers have rarely tested whether social programs designed to alleviate poverty or otherwise improve economic well-being for large segments of the population are linked with health improvements.6–9 The principal objective of our research agenda is to examine whether the earned income tax credit (EITC), a broad-based income support program that has been shown to increase employment and income among poor working families, also improves their health and access to care. We present preliminary analyses suggesting that such a relationship does exist, demonstrating the need for more empirical, multidisciplinary work in this area.

Background

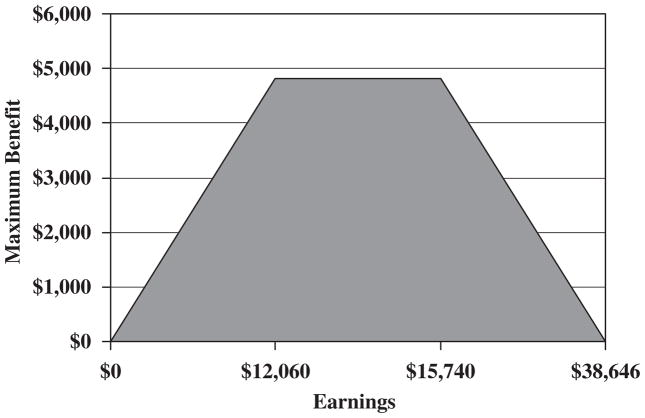

Established by Congress in 1975 and significantly expanded during the 1990s, the EITC is today the largest federal antipoverty program for the non-elderly in the United States. In 2006, more than 22 million families received nearly US$44 billion from the EITC. The EITC is a refundable credit originally designed to encourage work by offsetting the impact of federal taxes on low-income families and has been shown to increase employment, particularly among single mothers. According to one of the most comprehensive studies, the EITC accounted for nearly two-thirds of the rise in labor force participation by single mothers between 1984 and 1996.10 The amount of the credit increases with income, plateaus at a certain level of earning and then falls as it approaches the maximum earning level until reaching zero (Figure 1). With maximum benefits in tax year 2008 of $4824, the value of the EITC is substantial, particularly among the working poor.11 For example, the EITC would give a minimum wage worker with two children a 40 per cent increase in annual earnings. Owing to the refundable nature of the credit, even if workers have no federal income tax liability, as is true of most families below the poverty threshold, they can still receive the full value of the credit; thus, it effectively serves as a wage subsidy.

Figure 1.

Earned income tax credit parameters, 2008 (single parent families with >1 child).

Source: IRS.gov.

The positive relationship between income and health does not appear to be linear – large improvements in health are seen when moving up the income ladder from low to average or median levels, with increasingly diminishing returns to health from gains at high incomes.12 The EITC, as an income support program, has been highly successful at targeting families at the low end of the income distribution. More than half of the credit goes to families under the official poverty line, and nearly three-quarters is claimed by families earning less than $20 000 per year.13 It is estimated that 4.4 million people, more than half of them children, are removed from ‘poverty’ each year as a result of the EITC.11 Further, income support to families with young children, the focus of the EITC, may also provide material resources at a critical time. It may enhance child development and long-term positive health outcomes.14,15

In addition to the federal EITC, 23 states and the District of Columbia have implemented supplemental EITC programs.11 One study suggests that a universal refundable state EITC, pegged at 50 per cent of the federal rate, would lift an additional 1.1 million children out of poverty.16

The potential impact of the EITC can also be viewed by examining economic resources flowing into communities. For example, in 2005, 746 000 residents of New York City received more than $2.1 billion from the federal EITC.17 By combining the federal and state EITC refunds, a total of $2.8 billion or $9.3 million/square mile benefited New York City communities.

Spending on the federal EITC program now exceeds the combined levels of federal and state spending on what has been traditionally considered welfare. Since 1975, spending on EITC increased from less than $5 billion to nearly $44 billion in 2006. During the same time period, welfare spending (Aid to Families with Dependent Children/Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) increased from less than $15 billion to nearly $25 billion.18 Yet little is known about how or whether the EITC may affect families’ health or access to medical care.

Income support programs and the relationship to health

Other countries with poverty reduction or ‘make work pay’ programs similar to the EITC include the United Kingdom, Canada, France, Ireland, New Zealand, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, and the Netherlands. Many of these programs have been examined with respect to their impact on employment and household earnings and even on child test scores.19,20 Within the United States, there are no empirical studies examining the relationship between EITC and health outcomes.21 Theoretically, economists and others have suggested that the benefits of employment and good working conditions can positively influence health outcomes through enhanced financial security, social status, personal development, social relations and self-esteem, and protection from physical and psychosocial hazards.22,23

However, evidence linking income support policies to health outcomes is scarce or inconclusive and has focused on pension programs, like Social Security in the United States. A recent study by Snyder and Evans24 examined the impact of differing levels of Social Security benefits on mortality. As a result of changes made in the 1970s to lower program costs, beneficiaries with identical earning histories born before 1 January 1917 received larger benefits compared to those born just after that date. Beneficiaries with lower benefits were more likely to work longer and had lower mortality rates suggesting that source of income may be as important as the amount of income. The authors concluded that the time spent working decreased social isolation, a cofactor in mortality, suggesting that work has a positive health impact. However, those beneficiaries with lower benefits who worked longer also increased their earned income, leaving open the question whether the source or amount of income had a more significant effect on health outcomes. More recently, Herd et al,25 examined changes in Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits and changes in disability for beneficiaries 65 and older. They concluded that higher SSI benefit levels reduced disability in this group. In addition, in a preliminary analysis of the Old Age Assistance Program from 1930 to 1955, Balan-Cohen26 demonstrates an inverse relationship between income support for the poor elderly and mortality. These findings support the notion that income support policies have the potential for improving health outcomes.

At least two additional studies outside the United States consider the effect of government pension programs on health status. Case examined expanded payments in the South African pension system and found that within households where income was pooled with other earners, the state pension protected the health of all household members.27 The authors concluded that the pension income improved the nutritional status of household members and improved general living conditions. In a study of Russian households, Jensen and Kasper28 assessed the impact of the 1996 pension crisis. Households where pensioners went without benefits for a prolonged period of time were evaluated to determine the health impact. The authors found that poverty rates doubled, nutrition standards decreased, and pensioners who received no payments were 5 per cent more likely to die in the two years immediately following the crisis.

If a link between poverty reduction and health can be empirically validated, the potential for designing and implementing targeted income policies is enhanced. Moreover, progress in narrowing the disparity gap in health outcomes in all countries becomes more likely, especially in those countries where social insurance facilitates access to health care.

The Need for Empirical Evidence

Given the paucity of published research in this field, we undertook a series of preliminary analyses to establish the viability of examining the relationship between the EITC program and children’s health outcomes using existing data sets. In one analysis we evaluated the association between the EITC and children’s health insurance coverage by comparing poor households eligible for the EITC with a similar group of households who were not eligible for the credit.29 We used data from the Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the 2001 Current Population Survey (CPS) that estimates the eligible credit for each surveyed household, based on household composition, employment and income information. We focused on children in households headed by an unmarried woman or a married woman with absent spouse and low or moderate incomes, as these comprise the population that has experienced the greatest employment benefit from the EITC. Low or moderate income is defined here as a household income below $30 000. CPS sampling weights were applied.

We found that among mothers in our target population who were not eligible for the credit, 75 per cent reported all of their children lacked health insurance coverage. In contrast, among mothers who were eligible for the EITC, 54 per cent reported all of their children lacked health insurance coverage (P<0.00005). Thus, single mothers with low or moderate incomes who were ineligible for the EITC program were 1.4 times more likely to lack health insurance for all of their children than single mothers who were eligible to receive the credit. These differences in insurance coverage may be due to differences in mothers’ employment, and thus may reflect the impact of the EITC program on labor force participation. Additionally, there was interesting variation in the type of government health insurance coverage by parental eligibility for the EITC program. For example, the probability that all or some of the children in the household were covered by government insurance (Medicaid or SCHIP) declined (P<0.00005), whereas the probability that all or some were covered by private insurance increased for EITC-eligible households (P = 0.02). Studies have demonstrated that among children, health insurance coverage is strongly associated with improved access to primary care30 and more specifically, compared to those with private insurance, SCHIP-eligible children, and those enrolled in Medicaid are more likely to be in fair or poor health.31

In a second analysis, we examined the EITC’s potential to influence poverty-sensitive health indicators by evaluating the association between state-level EITC penetration among women and the infant mortality rate. EITC penetration was estimated using data from the Current Population Survey (1989–1996) and infant mortality rates were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics. Within each year, the EITC and mortality data were aggregated to the state level, stratified by race within state, with sample weighting accounted for. Using a random effects regression, we modeled the race-specific infant mortality rates from each state as a function of the proportion of such women who were eligible to receive the EITC among all women whose household incomes fell below the federal poverty level. This analysis also adjusted for the concurrent secular trend of declining infant mortality rates. We found a statistically significant inverse association between EITC penetration and infant mortality. The magnitude of this effect was strong: each 10-percentage point increase in EITC penetration (within or between states) is associated with a 23.2 per 100 000 reduction in infant mortality rate (P = 0.013). Consequently, it would take 8 years for the then-prevailing downward trend in infant mortality rates to reach the infant mortality rate that would occur if EITC penetration among impoverished women reached 100 per cent across all states. While suggesting a potential EITC influence on infant mortality, we need to consider potential confounding factors, particularly state-level poverty and employment rates and the concurrent changes in social welfare programs other than the EITC that varied by state.

Conclusions

A finding that the EITC has a positive impact on the health and health care of the public may help guide deliberations about its future at the federal, state and local levels. Our overall goal is to enhance our understanding of the relationship between major socioeconomic policies such as the EITC and the public’s health, thus broadening the perspectives of those in the fields of health and social policy and research.32

It is our belief that a better understanding of the link between our major social and economic policies and their potential health consequences would add an important and missing dimension to the public discourse over the future of programs such as the EITC and other tax policies. An empirical demonstration of these effects would suggest that we begin to think more broadly about the impact of economic and social welfare policies on population health and access to care.

Acknowledgments

Support for this paper was provided in part by an RWJF Investigator Award in Health Policy Research (Arno) from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, New Jersey and by grant P60-MD0005-03 from the National Centre for Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health (Arno, Schechter and Sohler).

Biographies

Peter S. Arno PhD, is an economist and Professor at the School of Public Health at New York Medical College and Director of the doctoral program in the Department of Health Policy and Management. His recent research has focused on the role of income support policies on population health outcomes, obesity, and health disparities. He studies pricing practices of the pharmaceutical industry and the economic impact of informal caregiving and long-term care.

Nancy Sohler, PhD, is an epidemiologist at the Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education of City University of New York. Her research focuses on evaluating health services for medically under-served populations and examining disparities in health and health care in the New York City area.

Deborah Viola, PhD, is Director of the MPH Program in the Department of Health Policy and Management, School of Public Health, New York Medical College. Her recent research interests have focused on the impact of preconception care on adverse birth outcomes, emergency preparedness for vulnerable populations, and the role of income support policies on population health.

Dr Clyde Schechter is a physician epidemiologist and Associate Professor of Family and Social Medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and is a Fellow of the American College of Preventive Medicine. His research activities span a broad range of clinical and methodological topics.

References and Note

- 1.Feinstein JS. The relationship between socioeconomic status and health: A review of the literature. The Milbank Quarterly. 1993;71:279–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams DR, Collins C. US socioeconomic and racial differences in health: Patterns and explanations. Annual Review of Sociology. 1995;21:349–386. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorlie PD, Backlund E, Keller JB. US mortality by economic, demographic, and social characteristics: The national longitudinal mortality study. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(7):949–956. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonough P, Duncan GJ, Williams D, House J. Income dynamics and adult mortality in the US, 1972 through 1989. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1476–1483. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.9.1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lantz PM, House JS, Lepkowski JM, Williams DR, Mero RP, Chen J. Socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and mortality. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279:1703–1708. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connor J, Rodgers A, Priest P. Randomized studies of income supplementation: A lost opportunity to assess health outcomes. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1999;53:725–730. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.11.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris P, Huston A, Duncan G, Crosby D, Bos J. How Welfare and Work Policies Affect Children: A Synthesis of Research. New York: MDRC; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bos J, Huston A, Granger R, Duncan G, Brock T, McLoyd V. New Hope for People with Low Incomes: Two-Year Results of a Program to Reduce Poverty and Reform Welfare. New York: MDRC; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Auspos P, Miller C, Hunter JA. Final Report on the Implementation and Impacts of the Minnesota Family Investment Program in Ramsey County. New York: MDRC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer B, Rosenbaum DT. Welfare, the earned income tax credit and the employment of single mothers. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2001;116(3):1063–1114. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levitie J, Koulish J. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 2008. Jun 6, [accessed 23 June 2008.]. State earned income tax credits: 2008 legislative update. www.cbpp.org. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robert SA, House JS. Socioeconomic inequalities in health: Integrating individual, community and societal-level theory and research. In: Albrecht G, Fitzpatrick R, Scrimshaw S, editors. Handbook of Social Studies in Health and Medicine. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scholz JK, Levine K. The evolution of income support policy in recent decades. In: Danziger S, Havemann R, editors. Understanding Poverty. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press; 2002. pp. 193–228. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen E, Martin AD, Matthews KA. Trajectories of socioeconomic status across children’s lifetime predict health. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e297–e303. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engle PL, Black MM. The effect of poverty on child development and educational outcomes. Annals of New York Academy of Science. 2008;1136:243–256. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Children in Poverty. Untapped Potential: State Earned Income Credits and Child Poverty Reduction. New York: National Center for Children in Poverty; 2001. Apr, Childhood Poverty Research Brief No. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brookings Institution. [accessed 27 June 2008.];EITC interactive. 2008 http://www.brookings.edu/projects/EITC.aspx.

- 18.Maag E. [accessed 25 June 2008];Urban Institute. 2008 http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/Maag-Thursdays_child_figures.pdf.

- 19.Pearson M, Scarpetta S. An overview: What do we know about policies to make work pay? OECD, Economic Studies. 2000;31:11–24. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dahl GB, Lochner L. The Impact of Family Income on Child Achievement. Institute for Research on Poverty; 2005. Aug, Discussion Paper No. 1305-05. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoynes H. Income Support Policies and Disparities in Health. NIH Conference on Understanding and Reducing Disparities in Health; 23–24 October; 2006. http://obssr.od.nih.gov/HealthDisparities/slideshow/13_Hoynes.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearson, et al. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marmot M, Wilkinson RG, editors. Social Determinants of Health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snyder S, Evans W. The effect of income on mortality: Evidence from the social security notch. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2006;88(3):482–495. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herd P, Schoeni RF, House JS. Upstream solutions: Does the supplemental security income program reduce disability in the elderly? The Milbank Quarterly. 2008;86(1):5–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balan-Cohen A. The effect of income on elderly mortality: Evidence from the Old Age Assistance Program in the United States. 2009 American Economic Association Conference Papers; 2009. [accessed 1 January 2009.]. http://www.aeaweb.org/assa/2009/author_papers.php?author_ID=6557. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Case A. Does Money Protect Health Status? Evidence from South African Pensions. NBER Working Paper no. 8495. In: Wise D, editor. Perspectives on the Economics of Aging. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2001. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen RT, Kaspar R. The health implications of social security failure: Evidence from the Russian pension crisis. Journal of Public Economics. 2008;88:209–236. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ideally, we would have compared the insurance status of children whose head of household claimed the EITC with children whose head of household did not claim the EITC. However, income tax return data that includes EITC claims and health insurance information are not currently available at the individual level.

- 30.Newacheck PW, Stoddard JJ, Hughes DC, Pearl M. Health insurance and access to primary care for children. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338:513–519. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802193380806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Byck GR. A comparison of the socioeconomic and health status characteristics of uninsured, state children’s health insurance program-eligible children in the United States with those of other groups of insured children: Implications for policy. Pediatrics. 2000;106:14–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Putnam S, Galea S. Epidemiology and the macrosocial determinants of health. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2008;29:275–289. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2008.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]