Abstract

Caenorhabditis elegans embryonic polarity requires the asymmetrically distributed proteins PAR-3, PAR-6 and PKC-3. The rho family GTPase CDC-42 regulates the activities of these proteins in mammals, flies and worms. To clarify its mode of action in C. elegans we disrupted the interaction between PAR-6 and CDC-42 in vivo, and also determined the distribution of GFP-tagged CDC-42 in the early embryo. Mutant PAR-6 proteins unable to interact with CDC-42 accumulated asymmetrically, at a reduced level, but this asymmetry was not maintained during the first division. We also determined that constitutively active GFP∷CDC-42 becomes enriched in the anterior during the first cell cycle in a domain that overlaps with PAR-6. The asymmetry is dependent on PAR-2, PAR-5 and PAR-6. Furthermore, we found that overexpression of constitutively active GFP∷CDC-42 increased the size of the anterior domain. We conclude that the CDC-42 interaction with PAR-6 is not required for the initial establishment of asymmetry but is required for maximal cortical accumulation of PAR-6 and to maintain its asymmetry.

Keywords: Embryonic polarity, Asymmetric cell division, Rho GTPase

Introduction

The establishment and maintenance of polarity are required for the proper function of many different eukaryotic cell types during development. Cell polarity is important for numerous cellular processes including the shaping of cell structure, and directing cell behaviors such as movement, growth, secretion and asymmetric division (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2002). The Caenorhabditis elegans genetic model organism has been very helpful for understanding polarity. In C. elegans, polarity is crucial for setting up the asymmetries required for the well-defined series of cleavages that establish the fates of the early embryonic blastomeres (Rose and Kemphues, 1998; Schneider and Bowerman, 2003). Polarity is first established during fertilization when the sperm centrosomes delineate the posterior end of the zygote (Cowan and Hyman, 2004b; Goldstein and Hird, 1996; Wallenfang and Seydoux, 2000). This event leads to the formation of the anterior/posterior (A/P) axis of the zygote. During the first cell cycle, a number of asymmetries are established including the polar partitioning of cell fate-determining factors, and a more posterior positioning of the mitotic spindle. As a result, at the end of mitosis the two daughter cells, AB and P1, differ in size and molecular composition (Rose and Kemphues, 1998; Schneider and Bowerman, 2003). The AB cell divides first, perpendicular to the long axis of the embryo, followed shortly thereafter by the P1 cell, which divides parallel to the long axis. Although there have been a number of important advances in understanding the mechanisms guiding polarity (Cowan and Hyman, 2004a; Pellettieri and Seydoux, 2002; Schneider and Bowerman, 2003), much of the detail remains to be discovered.

The PAR (partitioning-defective) proteins, first identified in C. elegans but subsequently found in a number of other organisms (Kemphues et al., 1988; Ohno, 2001), are among the earliest polarization cues. The PDZ (PSD-95, Discs Large, ZO-1) domain containing proteins PAR-3 and PAR-6, and the atypical protein kinase, PKC-3, are crucial for polarity establishment (Etemad-Moghadam et al., 1995; Hung and Kemphues, 1999; Tabuse et al., 1998). In C. elegans, these three proteins co-localize at the anterior cortex of the zygote in a process that is dependent on the actomyosin cytoskeleton, where they cooperate to restrict PAR-2, a cortically enriched RING-finger protein, to the posterior of the embryo (Munro et al., 2004). PAR-2 in turn acts antagonistically to PAR-3, PAR-6 and PKC-3 (the anterior PAR proteins), and is required to maintain the asymmetric localization of these proteins (Boyd et al., 1996; Cuenca et al., 2003). The mutual repression between the anterior PARs and PAR-2 produces an environment that enables PAR-1, a serine/threonine kinase, to be restricted to the posterior cortex (Pellettieri and Seydoux, 2002). PAR-1 is required to establish the asymmetry of a range of cytoplasmically enriched cell fate-determining proteins such as the partially redundant zinc-finger-containing proteins MEX-5 and MEX-6, as well as PIE-1 and P granules (Cheeks et al., 2004; Guo and Kemphues, 1995; Reese et al., 2000; Schubert et al., 2000). Thus PAR-2 and the anterior PAR proteins act to establish the initial zygotic polarity required for PAR-1 localization, allowing PAR-1 to properly regulate downstream cell fate-determining factors.

Although it is well established that the PAR proteins interact with each other to regulate polarity, what is less certain is how other molecules affect this process. Growing evidence from a number of organisms has implicated Cdc42 in the regulation of Par function (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2001; Gotta et al., 2001; Hutterer et al., 2004; Joberty et al., 2000; Johansson et al., 2000; Kay and Hunter, 2001; Lin et al., 2000; Qiu et al., 2000). Cdc42 is a member of the Rho family of GTPase signaling molecules that are activated by nucleotide exchange through the action of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and inactivated by the hydrolysis of GTP to GDP with the help of GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2002). In the active state, Cdc42 binds to and regulates a wide range of downstream effector molecules which each contain a Cdc42/Rac interaction binding (CRIB) domain (Burbelo et al., 1995; Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2002). These effectors control a large number of cellular functions including cytoskeletal organization, vesicular trafficking, cell cycle control and polarity establishment (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2003; Kroschewski et al., 1999; Yasuda et al., 2004). Although Par6 does not contain a complete consensus CRIB domain, it has been shown to bind to active Cdc42 in mammalian cells in an interaction that requires the semi-CRIB and PDZ protein regions (Garrard et al., 2003; Joberty et al., 2000; Johansson et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2000; Qiu et al., 2000).

In mammalian epithelial cells, Par3, Par6, and Pkcζ bind to each other and can form a complex in vivo with active Cdc42 (Joberty et al., 2000; Johansson et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2000; Qiu et al., 2000). These molecules were found to be essential for tight junction formation in MDCK cells, as overexpression of Par6 or Cdc42 results in the mislocalization of Par3 and disruption of tight junctions. In addition, in polarized astrocytes, it has been shown that Cdc42, Par6 and Pkcζ are essential for reorienting the microtubule organizing center, the cytoskeleton and the Golgi apparatus toward the direction of growth (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2001). Cdc42 is located in the perinuclear region and on the leading edge of these cells along with Par6 and Pkcζ. Binding of active Cdc42 was also shown to be necessary for establishing the apical localization of Par6 in Drosophila epithelial cells but not in neuroblasts (Hutterer et al., 2004). Together, these results indicate that local activation of CDC-42 can recruit PAR-6 and aPKC and direct cell polarization. Thus it appears that the Par proteins and Cdc42 function together to regulate polarity in a number of different contexts, although it is unknown whether the mechanisms by which they do this are conserved.

All this evidence suggests that Par3, Par6 and Cdc42 interact via a mechanism that is conserved in metazoans. In support of this, depletion of CDC-42 by RNAi results in polarity defects and the mislocalization of PAR-6 and PAR-2 in C. elegans (Gotta et al., 2001; Kay and Hunter, 2001). Furthermore, PAR-6, or a fragment of PAR-6 containing only the semi-CRIB and PDZ domains, was able to bind to active CDC-42 in yeast, further suggesting that this complex exists in worms (Gotta et al., 2001). However, the RNAi results leave open the question of whether the depletion of CDC-42 exerts its effect on polarity via its interaction with PAR-6 or via some other role in oogenesis or the early embryo.

To understand better how CDC-42 contributes to polarity establishment during early C. elegans embryonic development, we examined the regulatory relationship between CDC-42 and the PAR proteins using two different approaches: (1) disruption of the CDC-42/PAR-6 interaction in live animals and (2) determining the distribution of GFP tagged CDC-42 in various activation states. We find that CDC-42 exerts its affects on polarity primarily via its direct interaction with PAR-6; that activated CDC-42 is asymmetrically distributed and that asymmetric distribution of activated CDC-42 requires PAR-6, PAR-2 and PAR-5.

Materials and methods

C. elegans strains were cultured using standard techniques (Brenner, 1974). Strains used in this study were Bristol N2, KK747 par-2(lw32) unc-45(e286ts)/sC1 [dpy-1(e1)], and KK818 par-6(zu222) unc-101(m1)/hIn1 [unc-54(h1040)] I.

Production of transgenic lines

Most of the transgenic lines in this study were generated using the complex array method previously described (Kelly et al., 1997; Mello et al., 1991). Consequently most of the lines only transiently expressed the transgene due to germline silencing (Kelly et al., 1997), so all analysis was done within the first few generations. However, two stable lines, KK881, itIs160 [Ppie-1∷GFP∷PAR-6 unc-119(+)]; unc-119(ed3) and KK944, itIs164 [GFP∷PAR-6 CM2 unc-119 (+)]; unc-119(ed3), were produced using biolistic bombardment (Praitis et al., 2001). To recover transgenes expressed in the par-2 or par-6 homozygous backgrounds, we injected the transgenes into heterozygotes from KK747 or KK818, recovered Rol non-Unc F1 animals and then recovered Rol Unc animals in the F2 or F3 generations to collect images for movies. All transgenic lines were maintained at 25°C.

To disrupt the PAR-6-CDC-42 interaction, we made two mutants that each contained four clustered alanine substitutions in the C-terminal portion of the PAR-6 semi-CRIB domain. We did this because in previous studies, mutants containing double substitutions of conserved residues or a deletion of a single conserved proline did not eliminate the interaction with Cdc42 (Joberty et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2000). Therefore, we reasoned that other PAR-6-specific residues might be more important for binding. We modified the semi-CRIB domain of the par-6 cDNA using standard site-directed mutagenesis procedures to construct the following two mutants: CM1 (P135A D137A, F138A, R139A) and CM2 (V141A, S142A, I144A, I145A). The mutants were then cloned into the Spe I site of the pJAM vector, which we had previously constructed by inserting the pha-1 gene into the Sac II site of pJH4.52 (a gift from G. Seydoux; http://www.bs.jhmi.edu/MBG/SeydouxLab/vectors/vector_gen1.htm). We also modified this GFP expression vector to contain cfp∷par-6 or yfp∷cdc-42 q61l, again using site-directed mutagenesis and standard PCR techniques. Briefly, cfp and yfp were fused to par-6 and cdc-42 q61l respectively using PCR; the resulting fragments had BamHI ends that allowed replacement of the gfp∷par-6 sequences in the pJAM vector. These vectors were co-injected using the method described above to produce transgenic lines that expressed both.

Time-lapse microscopy

For live observations of GFP embryos, a focal plane through the center of the embryo was chosen. All embryos were imaged at approximately 22°C in egg buffer (118 mM NaCl; 40 mM KCl; 3.4 mM CaCl2; 3.4 mM MgCl2; 5 mM HEPES 7.4). Openlab software (Improvision Inc.), was used for image acquisition on a Leica DM RA2 microscope equipped with a 63× Leica HCX PL APO oil immersion lens and a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER digital camera. In most supplemental movies, the anterior of the embryo is positioned to the left.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

To visualize PAR-2, PAR-3 and GFP∷PAR-6 CM2 in situ, embryos were fixed on slides using established procedures (Guo and Kemphues, 1995). We used the following antibodies and concentrations: affinity purified rabbit anti-PAR-2 antibodies (Boyd et al., 1996) at 1/10 mouse monoclonal anti-PAR-3 antibodies (Nance et al., 2003) at 1/75, goat anti-GFP antibodies [Rockland Immunochemicals, Lot #13320] at 1/3000. Secondary antibodies include donkey anti-goat Cy3 1/400 (Jackson Immunochemicals), donkey anti-rabbit FITC 1/200 (Jackson Immunochemicals) and donkey anti-mouse AlexaFluor 1/500 (Molecular Probes).

RNA interference (RNAi)

Double-stranded RNA was made in vitro from L4440 plasmids (Timmons and Fire, 1998) containing the appropriate DNA sequences using a Promega RiboMAX kit. The dsRNA was injected into the gonad or the gut of animals (Fire et al., 1998). For par-6 and cdc-42, the complete open reading frames were used to produce dsRNA. Since par-5 has a close homolog in C. elegans, a 200-bp sequence specific to par-5 was used (Morton et al., 2002). For par-5(RNAi) and par-6(RNAi), time-lapse image sequences were captured of embryos dissected from injected parents that had recovered for 24 h at 25°C. For experiments to deplete endogenous PAR-6 in worms expressing transgenic PAR-6, we used a 361-bp sequence from the PAR-6 3′UTR. As has been reported previously for cdc-42(RNAi) (Kay and Hunter, 2001; Gotta et al., 2001) embryonic polarity defects can only be assayed under conditions that partially deplete CDC-42 protein; if CDC-42 protein levels drop beyond a critical threshold, the injected worms cease embryo production. To obtain embryos with reduced CDC-42 levels in the GFP∷PAR-6 transgenic line we kept the injected worms at 20°C for 12 h, followed by 24 h more at 25°C.

Yeast two-hybrid analysis

Mutagenesis of the semi-CRIB domain of PAR-6 was performed using PCR. Primer sequences are available upon request. The open reading frames of the mutants were cloned into PAS1-CYH and PACTII vectors (Durfee et al., 1993; Harper et al., 1993). These clones were tested against the appropriate matching clones of the inactive and constitutively active cdc-42 mutants (generous gifts from Monica Gotta), as well as par-3 and pkc-3. Two hybrid experiments were performed in the Pj69-4A yeast strain (James et al., 1996), and the His and Ade markers were used to test interaction.

Results

Mutations in the PAR-6 Semi-CRIB domain disrupt interaction with CDC-42

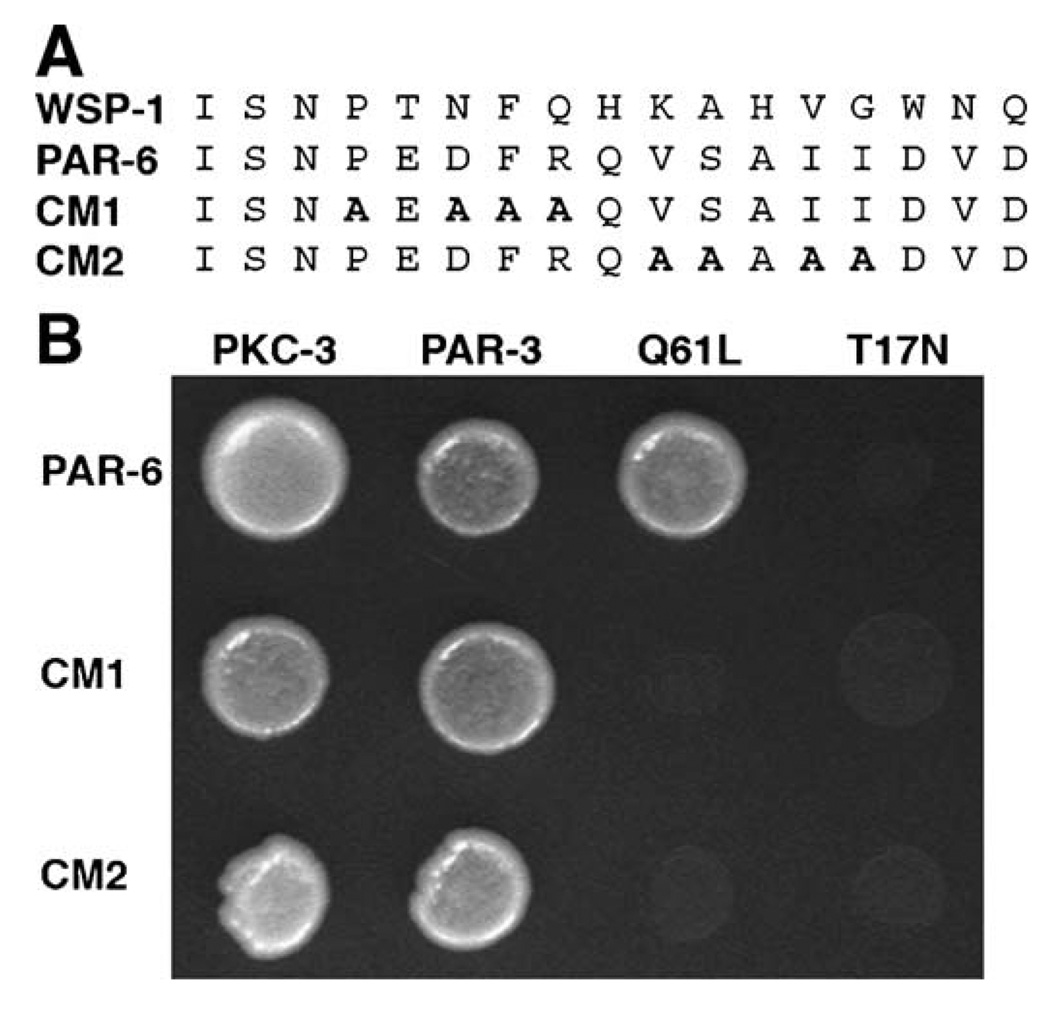

In mammals, Par6 interacts with active Cdc42 via the Par6 semi-CRIB and PDZ domains (Garrard et al., 2003; Joberty et al., 2000; Johansson et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2000; Qiu et al., 2000) and a similar interaction occurs between the C. elegans proteins in a two-hybrid assay (Gotta et al., 2001). In order to disrupt this interaction, we introduced mutations into the semi-CRIB domain of PAR-6.We made two mutants that each contain four clustered alanine substitutions in the C-terminal portion of the semi-CRIB domain (PAR-6 CRIB mutant 1 [CM1], PAR-6 CRIB mutant 2 [CM2]; Materials and methods and Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Mutations in the PAR-6 semi-CRIB domain disrupt interaction with CDC-42. (A) Alignment of the WSP-1 CRIB domain with the semi-CRIB domain of PAR-6. Amino acid substitutions introduced in the CM1 and CM2 mutants are in bold. (B) Yeast two-hybrid assay showing that both CM mutants are unable to interact with constitutively active CDC-42 (Q61L), but retain the ability to interact with PKC-3 and PAR-3.

CDC-42 binds to and regulates downstream effectors when bound to GTP, and is inactive when bound to GDP (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2002).We tested whether the PAR-6 semi- CRIB mutants could bind CDC-42 mutants that mimic the active and inactive states. CDC-42 (Q61L) is a mutant that is constitutively active, preferentially associating with GTP, while CDC-42 (T17N) is an inactive, dominant negative mutant (Ziman et al., 1991). When tested in a two-hybrid assay, wild-type PAR-6 is able to interact with CDC-42 (Q61L) and not with CDC-42 (T17N), while PAR-6 CM1 and PAR-6 CM2 are unable to interact with either of the CDC-42 mutants (Fig. 1B). The PAR-6 CM1 and PAR-6 CM2 mutants both retain the ability to interact with PKC-3 and PAR-3, showing that the overall protein structure is not seriously perturbed by the mutations.

Maintenance of PAR-6 asymmetry and function requires interaction with CDC-42

To see what effect the semi-CRIB mutations have on PAR-6 function in vivo, we made GFP fusion proteins and tested whether they could rescue the polarity defects of a par-6 loss-of-function mutant. We first tested whether GFP∷PAR-6 is able to rescue par-6(zu222). Using previously described methods (Cuenca et al., 2003; Kelly et al., 1997; Mello et al., 1991; Reese et al., 2000), we produced transgenic animals that expressed GFP∷PAR-6 under the control of the germline-specific pie-1 promoter. Since par-6 is maternal effect lethal, we looked for rescue of embryonic lethality in homozygous par-6 mothers that carried the transgene. Out of 6 transgenic lines, 5 exhibited rescue, showing that the GFP∷PAR-6 fusion protein can function normally in vivo (N=672/2053 or ~33% embryos hatched versus 0% for par-6 controls). The five rescuing lines expressed GFP∷PAR-6 in a pattern that matched the endogenous protein, as previously shown (Cuenca et al., 2003). PAR-6 is initially enriched around the entire cortex of the early embryo, and then becomes asymmetrically localized to the anterior cortex during pronuclear migration (Fig. 2 and Fig2video1). By the two-cell stage, PAR-6 is enriched mainly around the AB cell and the anterior-most portion of the P1 cortex (Cuenca et al., 2003; Hung and Kemphues, 1999). The single line that did not rescue did not express detectable levels of PAR-6.

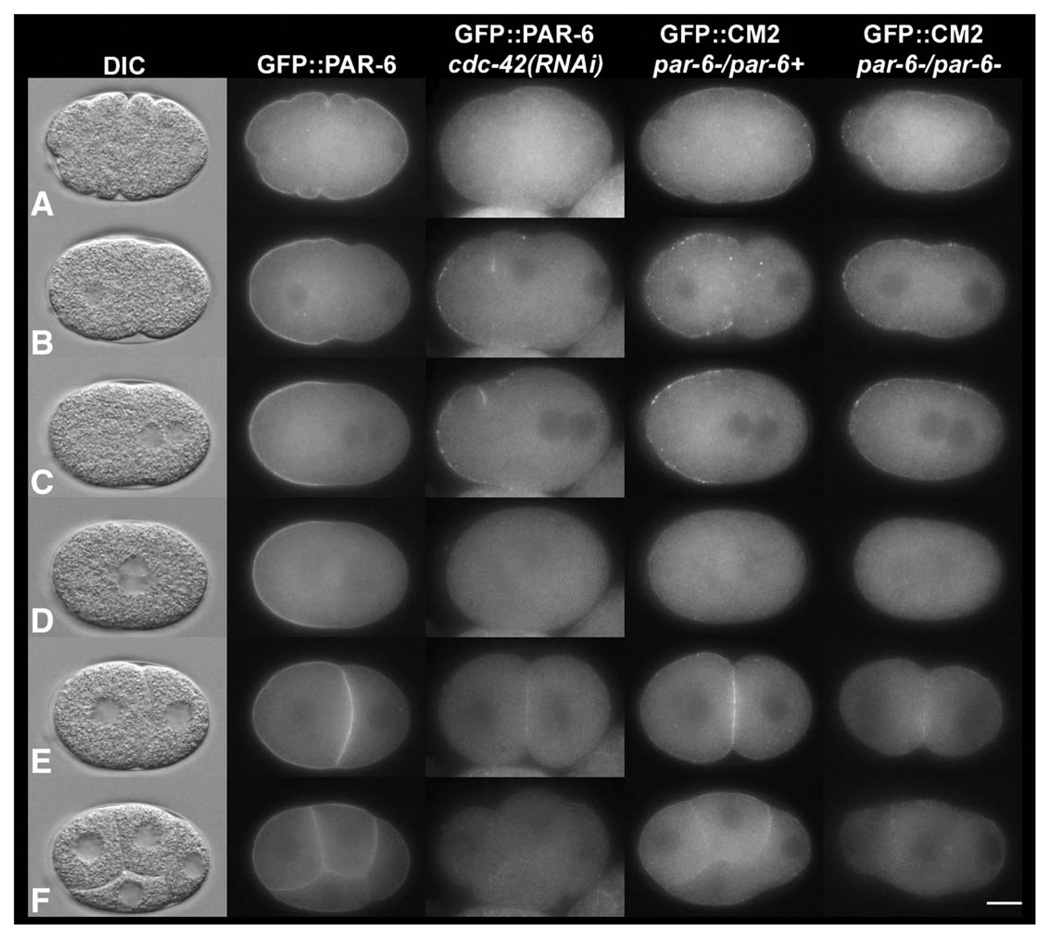

Fig. 2.

The CM1 and CM2 mutants display localization defects similar to cdc-42(RNAi) embryos. Still images from time-lapse movies (Fig2video1; Fig2video2; Fig2video3; Fig2video4) at (A) pronuclear formation, (B) pronuclear migration, (C) pronuclear meeting, (D) nuclear envelope breakdown, (E) 2 cell, and (F) four-cell stages of development. The CM1 and CM2 mutant proteins are unable to function normally in vivo, and lose asymmetry between late pronuclear migration and nuclear envelope breakdown. The phenotypes of the CM1 and CM2 mutants are identical and phenocopy cdc-42(RNAi) embryos. In this and subsequent figures anterior is to the left. In cdc-42(RNAi) embryos, CDC-42 was depleted by injecting dsRNA in a GFP∷PAR-6 strain. GFP∷CM1 and GFP∷CM2 were expressed in a par-6 null mutant strain (see Materials and methods), and filmed in heterozygous and homozygous par-6 mutants (only GFP∷CM2 is shown). The scale bar is approximately 10 µM in length. Images were taken from the following supplemental videos: Fig2video1, Fig2video2, Fig2video3 and Fig2video4.

Next we expressed the GFP-tagged semi-CRIB mutants in vivo. Neither one is able to rescue par-6(zu222) lethality (N=3230 embryos from 7 lines for CM1, and N=4191 embryos from 8 lines for CM2). Careful examination of the embryos from the CM1- and CM2-expressing worms revealed no difference in phenotype from control par-6(zu222). To determine whether blocking binding to CDC-42 had any effect on PAR-6 distribution, we examined the GFP in embryos taken from homozygous and heterozygous par-6 worms. Both semi-CRIB mutant proteins have identical protein distribution defects (Fig. 2; Fig2video2 and Fig2video3). Like endogenous PAR-6, the semi-CRIB mutant proteins are distributed initially around the entire cortex, and then appear to become asymmetrically enriched in the anterior during pronuclear migration like the wild-type protein (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Fig. 1). However, the protein does not accumulate at normal levels on the cortex, appearing punctate as opposed to the more uniform distribution seen in wild type. Distinct puncta are visible in the cytoplasm of many of these embryos. In addition, there is a precipitous loss of the protein from the cortex starting at nuclear envelope breakdown (Fig. 2). After cleavage, the mutant proteins reappear uniformly along the cortices of both daughter cells.

The mutant proteins behave similarly in progeny from either par-6 heterozygotes or homozygotes with a few exceptions. Less mutant protein is detectable at the cortex in the homozygotes (Fig. 2; Fig2video2 and Fig2video3). In addition, although there is no loss in asymmetry prior to cortical protein disappearance in embryos from heterozygous worms, in homozygous progeny some of the protein begins to regress back into the posterior immediately prior to mitosis (N=20/21 embryos for CM1; N=6/8 embryos for CM2 and Fig2video3). Finally, the semi-CRIB mutant proteins do not retract as far into the anterior in homozygous embryos (Fig. 2 and Fig2video3) (N=6/9; Fig. 2; Fig2video4 and see below). There are no obvious dominant negative effects associated with CM1 or CM2 expression in the heterozygous par-6 background, even in a stable line, KK944 (see below) that expresses theCM2 protein at a higher level than wild-type protein (data not shown); embryo viability does not differ from controls and cleavage patterns are normal. It is possible, however, that lines with even higher levels of expression could give dominant negative effects, but that such lines could not be recovered.

Previous analysis of anterior PAR proteins’ behavior in cdc-42(RNAi) embryos was performed on fixed embryos using immunolocalization (Gotta et al., 2001; Kay and Hunter, 2001). To examine the dynamics of PAR-6 distribution in response to depletion of CDC-42 in living embryos, we followed GFP∷PAR-6 in cdc-42(RNAi) embryos (N=9; Fig. 2 and Fig2video4). Cortical PAR-6 levels are reduced, distribution is punctate and defects in polarity are similar to those of the CM1 and CM2 mutants (Fig. 2; Fig2video3 and Fig2video4).

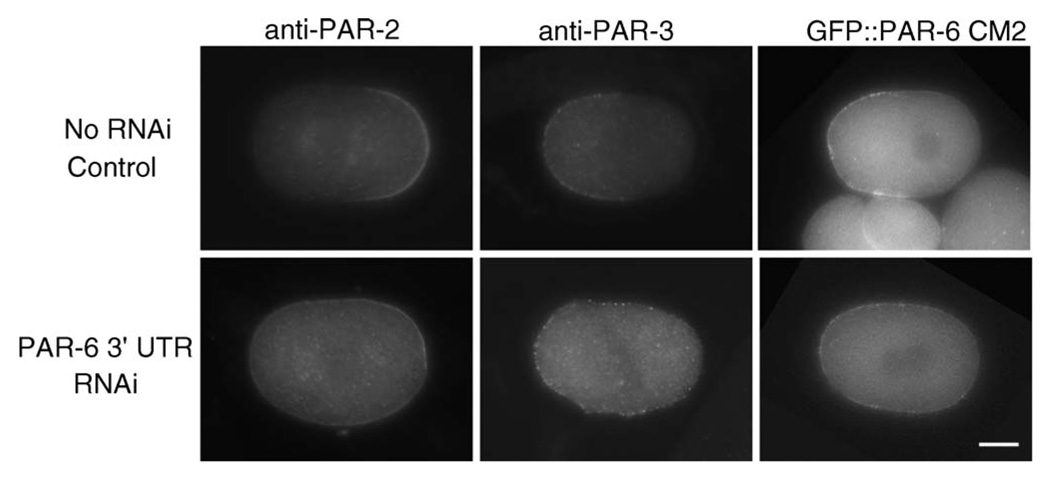

In cdc-42(RNAi) embryos PAR-2 and PAR-3 are also mislocalized (Gotta et al., 2001; Kay and Hunter, 2001). To determine whether this effect is mediated through PAR-6 or via a requirement for CDC-42 that is independent of PAR-6, we compared the distributions of PAR-2 and PAR-3 in the CM2 mutant embryos to those described for cdc-42(RNAi). To do this we first generated a transgenic lines expressing GFP∷PAR-6 CM2 using biolistic bombardment and recovered a line that retained germline expression (KK944; see Materials and methods). Our attempts to generate worms carrying this transgene in a homozygous par-6 mutant background were unsuccessful, so we used RNAi directed against the 3′UTR of par-6 to specifically target the endogenous mRNA in KK944 (the pie-1 3′UTR replaces the par-6 UTR in the transgene). As controls, we first showed that targeting the 3′UTR of PAR-6 could produce a loss-of-function PAR-6 phenotype in a wild-type genetic background (413/421 embryos failed to hatch) but not in KK881, a strain expressing GFP∷PAR-6 under the control of the pie-1 3′UTR (31/254 embryos failed to hatch), indicating that the RNAi was effective and specific and that expression of GFP∷PAR-6 could rescue the depletion of the endogenous protein. We then depleted endogenous PAR-6 in the KK944 strain and found that the CM2 mutant could not rescue the RNAi effect, as expected from our previous experiments with transient expression lines. We obtained further evidence for the specificity of RNAi for endogenous PAR-6; all eleven sampled one-cell embryos retained easily detectable GFP∷PAR-6 CM2 (Fig. 3) and showed clear Par-6 phenotypes. In siblings of these embryos, shown in Fig. 3, we found that PAR-2 and PAR-3 were expressed in patterns similar to those described for these proteins after RNAi depletion of CDC-42 (Gotta et al., 2001; Kay and Hunter, 2001). Specifically, whereas PAR-2 and PAR-3 distributions were normal in embryos from uninjected KK944 worms (n=14 and n=11 respectively), in 13/15 late prophase one-cell embryos from RNAi-treated worms, PAR-3 remained asymmetric but extended further into the posterior and was reduced in level; in the other two embryos, PAR-3 extended the full length of the embryo. We could not detect cortical PAR-3 in any of 10 one-cell metaphase embryos. In 14/18 late prophase or metaphase one-cell embryos, PAR-2 was uniformly distributed on the cortex. In three embryos the protein extended partly beyond its normal distribution into the anterior and in one embryo there were patches of PAR-2 in both the anterior and posterior.

Fig. 3.

CM2 mutants display defects in PAR-2 and PAR-3 distributions similar to those reported for cdc-42(RNAi) embryos. All embryos are from KK944 and thus carry the GFP∷PAR-6 CM2 transgene in a par-6(+) background. Top row: uninjected control embryos. Bottom row: embryos fixed or digitally imaged 20 h after RNAi injection. Note the symmetric and reduced PAR-2 signal, the expanded anterior domain of PAR-3, and the persistence of the GFP∷PAR-6 CM2 signal after RNAi-targeting of the endogenous protein. The scale bar is approximately 10 µM in length.

We conclude that CDC-42 exerts its effect on polarity primarily via its direct physical interaction with PAR-6 and that this interaction is specifically required to enhance cortical accumulation and maintain PAR-6 asymmetry.

Constitutively active CDC-42 becomes asymmetrically localized during embryogenesis

To gain more insight into how CDC-42 regulates polarity establishment, we followed its localization using GFP fusion proteins. Previous attempts to examine CDC-42 distribution in C. elegans using antibodies have been unsuccessful (Gotta et al., 2001). We first expressed unmodified GFP∷CDC-42 under the control of the pie-1 promoter to see total CDC-42 protein distribution. We found that GFP∷CDC-42 is present in the cytoplasm and is enriched in cortical patches around all cells during development (N=12 from 10 lines; Fig. 4 and Fig4video1). The cortical patches are especially evident on ruffled and invaginated cortex, and the GFP often appears slightly enriched in the perinuclear region, and on centrosomes (data not shown).

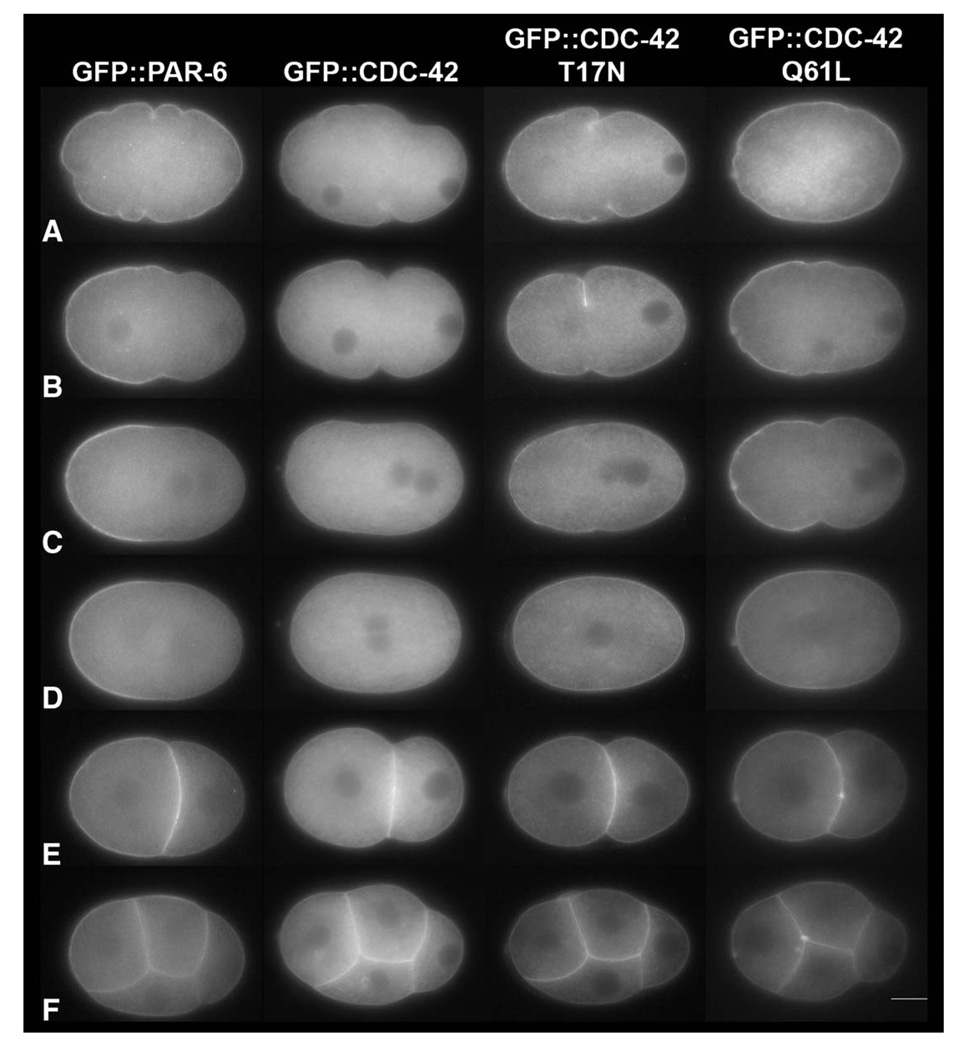

Fig. 4.

CDC-42 (Q61L) becomes asymmetrically enriched on the anterior cortex. Still images from time-lapse movies (Fig1video1; Fig3video1; Figvideo2) at (A) pronuclear formation/early migration, (B) pronuclear migration, (C) pronuclear meeting, (D) nuclear envelope breakdown, (E) the two-cell, and (F) four-cell stages of development. All GFP lines were made in the N2 background (see Materials and methods). Only the constitutively active mutant of CDC-42 (Q61L) becomes asymmetrically localized in a similar spatial and temporal manner as PAR-6. Both unmodified CDC-42 and the inactive mutant of CDC-42 (T17N) are symmetrically localized on the cortex. The scale bar is approximately 10 µM in length. Images were taken from the following supplemental videos: Fig2video1, Fig4video1, Fig4video2 and Fig4video3.

We next determined whether the active and inactive forms of CDC-42 have distinct cellular distributions. We made constructs to express the constitutively active CDC-42 Q61L mutant protein and the inactive CDC-42 T17N mutant protein under the control of the pie-1 promoter. The proteins behaved as expected in two-hybrid assays (Fig. 1B), so we constructed transgenic worms carrying each of the CDC-42 mutant constructs.

In four lines expressing GFP-tagged CDC-42 T17N, the distribution of the mutant protein is similar to that of unmodified CDC-42 (N=19 and Fig. 4). In contrast, the constitutively active mutant, CDC-42 Q61L, becomes highly enriched on the anterior cortex in a pattern resembling that of the anterior PAR proteins (N=35 from 8 lines; Fig. 4 and Fig4video2). Early in the first cell cycle, before the maternal pronucleus migrates to the posterior, GFP∷CDC-42 Q61L is enriched around the entire cortex. Then GFP begins to accumulate on the anterior cortex. After the first cell division, cortical CDC-42 Q61L is enriched around AB relative to P1, and by the four-cell stage, CDC-42 Q61L is present to a lower degree around P2 (Fig. 4 and Fig4video2).

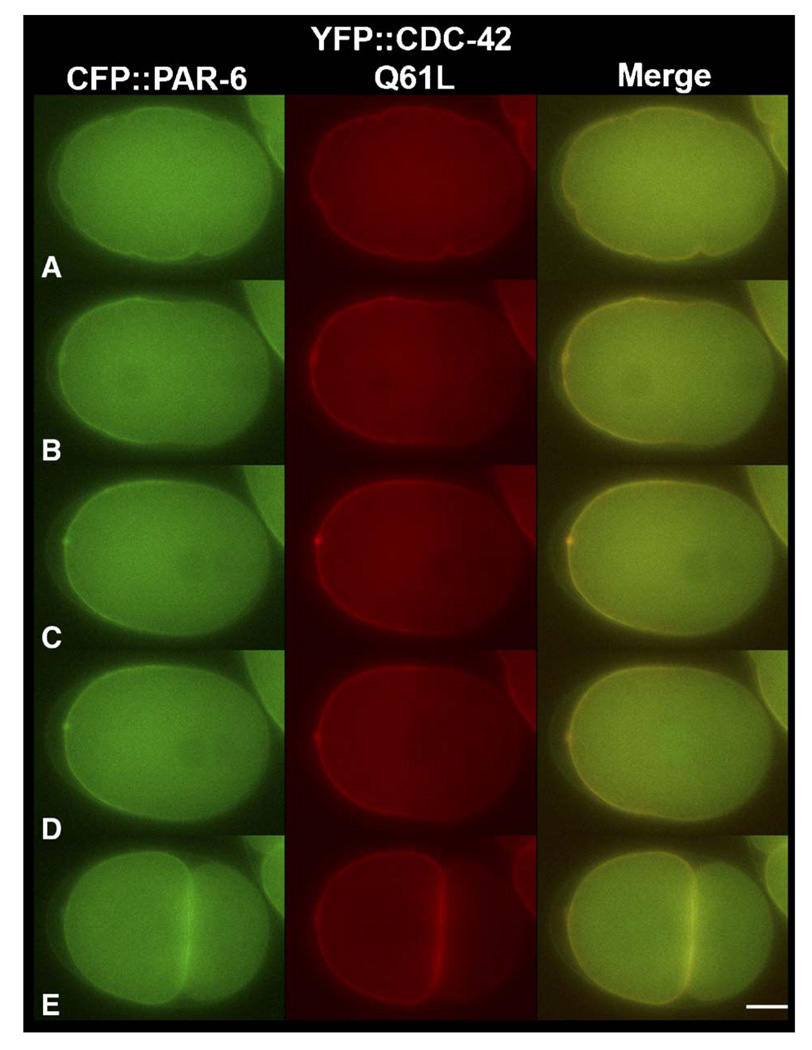

The timing and extent of CDC-42 Q61L asymmetry appear to coincide with PAR-6. To determine whether the two proteins co-localize, we co-expressed CFP-tagged PAR-6 and YFP-tagged CDC-42 Q61L in wild-type embryos. Both proteins overlap on the cortex (N=11 from 2 lines and Fig. 5). Since in some embryos the cortical domain of active CDC-42 appeared to extend further into the posterior than is typical for PAR-6, we tested whether overexpression of constitutively active CDC-42 might drive the anterior PAR proteins further into the posterior. Indeed, in embryos expressing both CFP∷PAR-6 and YFP∷CDC-42 Q61L, the boundary of the PAR-6 domain extends further into the posterior than GFP∷PAR-6 controls at the two time points we measured, pronuclear meeting and nuclear envelope breakdown (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Fig. 5.

PAR-6 and CDC-42 (Q61L) co-localize during embryogenesis. Still images from time-lapse movies at (A) pronuclear formation, (B) pronuclear migration, (C) pronuclear meeting, (D) nuclear envelope breakdown, and (E) the two-cell stage. CFP∷PAR-6 and YFP∷CDC-42 Q61L localization overlap when co-expressed in N2 worms, suggesting that active CDC-42 is associating with the anterior PAR complex. The scale bar is approximately 10 µM in length.

Both constitutively active and inactive mutants act as dominant negatives when overexpressed in yeast, flies, and mammalian cells, causing defects in cell polarity (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2001; Hutterer et al., 2004; Richman et al., 2002; Ziman et al., 1991). In contrast, we observe no negative effects on embryonic viability relative to uninjected controls in the three CDC-42 T17N lines we checked and all of the embryos whose early development we recorded had normal polarity (N=19). It is important to note, however, that the methods of recovering transgenic lines could result in selection against transgenic arrays giving dominant negative effects. For CDC-42 Q61L, however, our transgenic lines did show 6–31% embryonic lethality (compared to 1.5% for uninjected controls). Furthermore, embryos from all four lines expressing this CDC-42 mutant exhibit elevated levels of polarity defects that include symmetric cleavages, synchronous divisions, and spindle orientation defects (N=10/35; Supplemental video1). Often in these embryos, GFP∷CDC-42 Q61L fails to clear from the posterior or is not properly maintained in the anterior (Supplemental video1 and data not shown). These observations are consistent with our suggestion that the overall level of active CDC-42 is important for determining the size of the anterior domain.

CDC-42 (Q61L) asymmetry requires PAR-6, PAR-5, and PAR-2

Since the previous experiments suggested that active CDC-42 associates with the anterior PAR complex, we next tested whether the PAR proteins are required for CDC-42 Q61L asymmetry. Although evidence in mammals strongly suggests that localized Cdc42 activation is required for the asymmetric localization of the Par proteins (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2001; Joberty et al., 2000; Johansson et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2000; Qiu et al., 2000), our results suggest that in C. elegans the PAR proteins might be required to asymmetrically localize active CDC-42. To address this, we expressed GFP∷CDC-42 Q61L in different par backgrounds.

When GFP∷CDC-42 Q61L is expressed in par-6(zu222) embryos, it no longer becomes restricted to the anterior cortex (N=15 embryos from 4 lines; Fig. 6 and Fig6video1). Before pronuclear migration, CDC-42 Q61L is located uniformly around the embryonic cortex. When the pronuclei become visible, immediately preceding the detachment of the paternal pronucleus from the cortex, there is a very transient and limited clearing of GFP∷CDC-42 Q61L at the tip of the posterior cortex (Fig. 6). In addition, GFP∷CDC-42 Q61L is not as smoothly distributed as in the N2 background (Fig. 6 and Fig6video1).

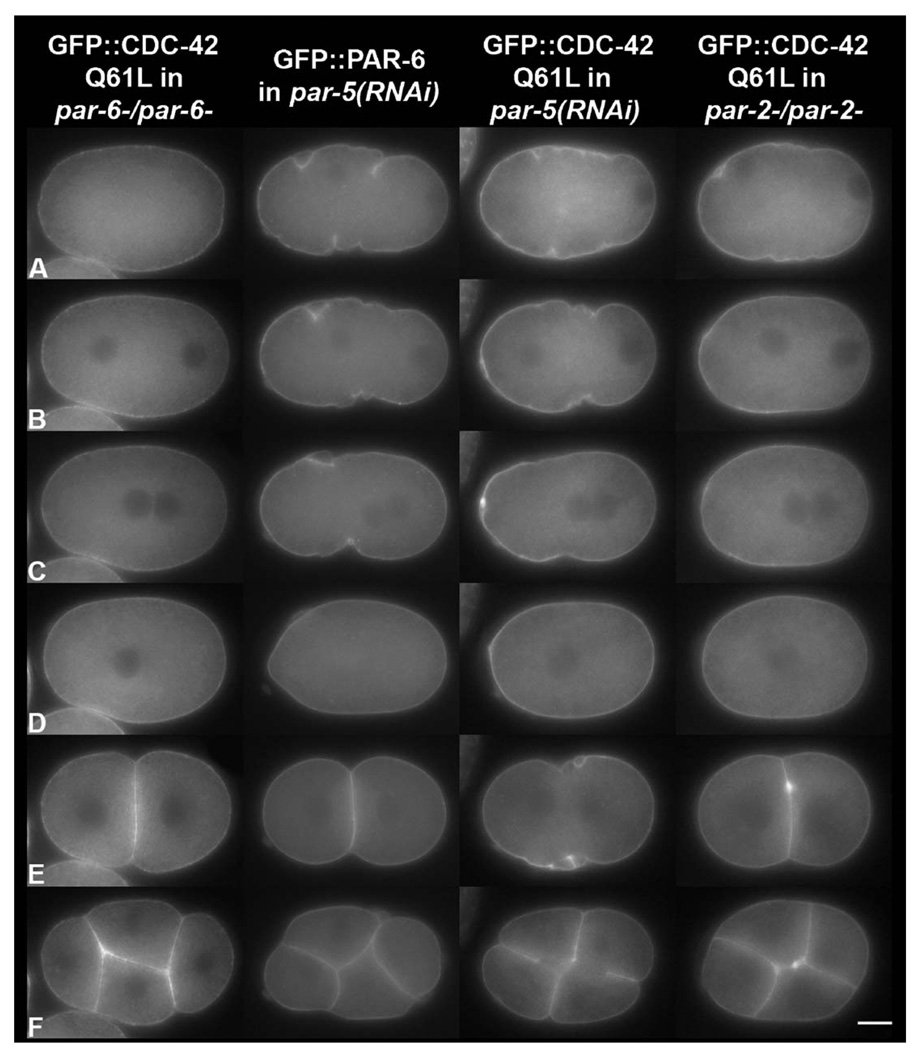

Fig. 6.

The establishment and maintenance of CDC-42 (Q61L) asymmetry requires PAR-6, PAR-5 and PAR-2. Still images from time-lapse movies (Fig5video1; Fig5video2; Fig5video3) at (A) pronuclear formation/early migration, (B) pronuclear migration, (C) pronuclear meeting, (D) nuclear envelope breakdown, and (E) the 2 cell and (F) 4 cell stages of development. The PAR proteins are required for CDC-42 asymmetry. CDC-42 localization is regulated similarly to PAR-6, providing further evidence that CDC-42 is a component of the anterior PAR complex. Notice the slight posterior cortical clearing of GFP in the par-6-/par-6- and par-5(RNAi) embryos, and the cytokinesis defects in the par-5(RNAi), GFP∷CDC-42 Q61L embryo. The scale bar is approximately 10 µM in length. Images were taken from the following supplemental videos: Fig6video1, Fig6video2 and Fig6video3.

PAR-5 is required to properly localize the anterior complex (Cuenca et al., 2003; Morton et al., 2002). Therefore, we used RNAi to deplete PAR-5 in embryos expressing GFP∷CDC-42 Q61L. In par-5(RNAi) embryos, GFP∷CDC42 Q61L distribution is very similar to that described for GFP∷PAR-6 (Cuenca et al., 2003; N=10; Fig. 6 and Fig6video2). There is a very slight posterior clearing of the protein early on, but full asymmetry is never established. This localization is also very similar to that in the par-6 background, except the protein is more smoothly distributed.

Depletion of PAR-5 from embryos expressing GFP∷CDC-42 Q61L results in an unexpected phenotype at high frequency-defective cytokinesis (Fig. 6 and Fig6video2). In par-5(RNAi) embryos, 10% (N=19) have cytokinesis defects and only 5% (N=21) of embryos expressing GFP∷CDC-42 Q61L exhibit cytokinesis defects. In contrast, 89% (N=18) of PAR-5 depleted GFP∷CDC-42 Q61L embryos have cytokinesis defects. Typically, when cytokinesis fails, there is considerable cortical blebbing at the expected site of contractile ring formation (see column 3, row E of Fig. 6) and often a transient invagination occurs. It is not clear from our limited number of observations whether the primary defect is in furrow initiation or furrow completion.

Next we looked at what effect par-2 mutation would have on active CDC-42 localization. We expressed GFP∷CDC-42 Q61L in par-2(lw32) (Boyd et al., 1996) and found that active CDC-42 diminished from the posterior during pronuclear migration, but in 9/12 embryos GFP∷CDC-42 Q61L returned to the posterior before mitosis was complete (Fig. 6 and Fig6video3), behaving similarly to PAR-6 in the same genetic background (Cuenca et al., 2003). In three embryos asymmetry was maintained and they divided normally, consistent with the previous observation that par-2 mutations are incompletely penetrant (Cheng et al., 1995).

Discussion

CDC-42 binding enhances PAR-6 cortical accumulation and maintains PAR asymmetry

RNAi-mediated partial depletion of CDC-42 in C. elegans had suggested that CDC-42 has a role in regulating embryonic polarity and PAR protein localization (Gotta et al., 2001; Kay and Hunter, 2001), but it was unclear whether this was due to a direct interaction between CDC-42 and PAR-6. We report here that blocking the PAR-6-CDC-42 interaction in vivo resulted in polarity defects very similar to those associated with cdc-42 (RNAi). However, other phenotypes observed in cdc-42(RNAi) worms and embryos, including defective oogenesis (Gotta et al., 2001; Kay and Hunter, 2001), defects in meiosis, mitotic spindle formation, and cytokinesis did not appear (D.A., K.K., unpublished data). Thus, although CDC-42 does have other roles in oogenesis and the early embryo, its role in regulating polarity is mediated largely through its interaction with PAR-6.

The semi-CRIB mutations, CM1 and CM2, affected the localization of PAR-6 in three ways: (1) the two mutant proteins had reduced levels and a punctate appearance on the cortex; (2) the proteins initially became asymmetrically localized to the anterior cortex, but lost asymmetry over time; (3) the proteins disappeared precipitously from the cortex during late prophase.

From the earliest time of data collection, the semi-CRIB mutant protein accumulated at the cortex to a lesser extent than wild-type PAR-6. This was especially apparent in early embryos before cortical PAR-6 becomes asymmetric. It is unlikely that the mutations simply caused protein instability because control GFP∷PAR-6 is reduced at the cortex to an equivalent degree after RNAi-mediated-CDC-42 depletion. The punctate distribution can be explained in two ways: either interaction with CDC-42 is required to efficiently recruit or maintain PAR-6 cortically, or CDC-42 promotes the smooth distribution of PAR-6. In fact, both appear to be contributing. In a related study, we obtained evidence that PAR-6 can bind to the cortex in two different modes and that CDC-42 is required for only one mode of binding (Beers and Kemphues, in press). Another interesting question is whether interaction with CDC-42 influences the extent to which PAR-6 is able to bind to PAR-3 and PKC-3. We expect that the PAR-6 CM1 and CM2 mutants likely retain some capacity to interact with PAR-3 and PKC-3 in vivo, since reduction of either of these proteins completely blocks PAR-6 cortical accumulation (Tabuse et al., 1998; Hung and Kemphues, 1999).

The most telling result from observations of the semi-CRIB mutant proteins is that, in spite of their lower abundance, they still became enriched along the anterior cortex in response to the polarity cue. The timing of this enrichment did not appear to deviate from wild-type embryos, nor largely did the extent to which the proteins became localized in the anterior. This suggests that the actomyosin-dependent process that directs the redistribution of PAR-6 (Munro et al., 2004) is still intact. Indeed in cdc-42(RNAi) embryos, there are no obvious defects in membrane ruffling, pseudocleavage, or in the integrity of actin filaments (Kay and Hunter, 2001), suggesting that the actomyosin cytoskeleton is functioning properly. This is consistent with the observation that depletion of components of the Cdc42-activated Arp2/3 complex involved in microfilament nucleation does not affect cortical dynamics (Severson et al., 2002).We cannot rule out the possibility that the ability of CM1 and CM2 mutant protein to respond to the polarity cue is due to residual ability, below the detectability of the two-hybrid assay, of both of the mutant proteins to bind to CDC-42. However, the simplest interpretation of our results is that PAR-6 interaction with CDC-42 is not required for the initial cytoskeletal-directed establishment of polarity and PAR asymmetry as was suggested by observations in cdc-42(RNAi) embryos (Gotta et al., 2001).

Not surprisingly, the mutant proteins behave differently in wild-type and heterozygous par-6 backgrounds versus homozygous par-6 backgrounds. Defects seen in the heterozygous background reflect the direct consequences to the CM1/2 proteins of their inability to bind CDC-42; additional defects seen in the homozygous background reflect the consequences of failure of the CM1/2 proteins to affect other polarity components (e.g., PAR-3 and PKC-3). In the homozygous par-6 background, the semi-CRIB mutant proteins are less effectively restricted to the anterior initially and exhibit a posterior regression that begins during pronuclear centering, suggesting that this may be the point during the cell cycle when CDC-42 function becomes necessary for polarity maintenance. However, we cannot rule out a role for the CDC-42/PAR-6 interaction in the later stages of polarity establishment.

Coincident with nuclear envelope breakdown, the semi-CRIB mutant proteins disappeared rapidly from the cortex. This late prophase disappearance is reminiscent of the behavior of the PAR-3 protein in both par-6 mutant embryos and pkc-3(RNAi) embryos (Tabuse et al., 1998; Watts et al., 1996). Thus maintenance of PAR-3 on the cortex through mitosis requires PAR-6 and PKC-3 and maintenance of PAR-6 requires binding to CDC-42.

Active CDC-42 co-localizes with PAR-6 In vivo

To understand better how CDC-42 functions with the PARs to control polarity, we asked whether activation state influences CDC-42 localization. The localization of CDC-42 has been determined in yeast and in various types of mammalian cells including astrocytes, MDCK cells, and T cells (Cannon et al., 2001; Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2001; Michaelson et al., 2001; Richman et al., 2002). In yeast, GFP∷Cdc42 is present on vacuolar and nuclear membranes and is localized on the plasma membrane around the entire cell periphery. Cdc42 then becomes enriched during the cell cycle to sites of polarized growth. In mammalian MDCK cells, GFP-tagged Cdc42 is located on endomembranes, especially along the ER, golgi and nucleus, and is also distributed uniformly along the plasma membrane (Michaelson et al., 2001). However, in migrating astrocytes, CDC-42 adopts a polar enrichment along the plasma membrane at the leading edge of the cell, in addition to endomembrane localization (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2001).

In many of these biological systems, Cdc42 proteins locked in different activation states exhibit very similar localization patterns to the expressed wild-type protein (Michaelson et al., 2001; Richman et al., 2002). In MDCK cells, both constitutively active and inactive Cdc42 are present, like wild-type Cdc42, around the entire plasma membrane (Michaelson et al., 2001). In yeast, it also appears that both active and inactive Cdc42 are located along the plasma membrane and cluster at polarized growth sites during the cell cycle (Richman et al., 2002). We found that a mutant that is constitutively active (Q61L) became enriched asymmetrically in the early embryo in a pattern that overlapped with PAR-6 whereas unmodified CDC-42 and a mutant CDC-42 with no activity (T17N) showed no detectable asymmetry. However, we note that the signal at the one-cell stage was weak in these embryos.

With the exception of a very transient and restricted posterior clearing, CDC-42 Q61L asymmetry is eliminated in a par-6 mutant. This suggests either that the asymmetry of active CDC-42 requires binding to PAR-6 or that active CDC-42 bound to some other cortical component is cleared from the posterior in a par-6-dependent manner. Assuming the simpler of these two possibilities, we propose that the active CDC-42 becomes associated and localized with the anterior PAR complex. In support of this, par-2 mutation and RNAi depletion of PAR-5 affect CDC-42 Q61L asymmetry in much the same way they affect PAR-6 (Boyd et al., 1996; Cuenca et al., 2003; Morton et al., 2002).

The persistent failure of PAR depletions to prevent a small amount of PAR-6 and CDC-42 Q61L posterior cortical clearing suggests that the initial polarity signal from the sperm centrosomes causes a change in local cortical properties independently of the PAR proteins. However, the small size and rapid disappearance of the clearing indicate that propagation of the cortical changes requires the PAR proteins. Munro and colleagues reached a similar conclusion by observing the clearing of myosin foci in par mutant embryos (Munro et al., 2004).

Our data also suggest that CDC-42 may influence how far PAR-6 extends along the posterior embryonic cortex. In the presence of excess active CDC-42, the PAR-6 cortical domain extends further into the posterior of the embryo. This is consistent with evidence that CDC-42 and PAR-2 act antagonistically to localize PAR-3 (Kay and Hunter, 2001). We also noticed that expression of CDC-42 Q61L led to weakly penetrant cytokinesis defects that were greatly enhanced by PAR-5 depletion. This suggested that PAR-5, a 14-3-3 protein, plays a previously unrecognized role in cytokinesis. Indeed, our analysis of par-5(RNAi) embryos showed low penetrance cytokinesis defects that had not previously been reported. The involvement of CDC-42 in cytokinesis is not clear. A possibility is that expression of constitutively active CDC-42 interferes with the activity of another Rho GTPase, RhoA, which is known to have a role in cytokinesis (Severson and Bowerman, 2002; D.A., K.J.K., unpublished results).

The role of CDC-42 activation in polarity establishment

One model for the role of CDC-42 in C. elegans polarity establishment has been suggested by studies of rat astrocytes in culture (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2001, 2003). Experiments in this system suggest that integrin signaling activates Cdc42 at the leading edge of the migrating cells. Active Cdc42 then recruits Par6 to the cortex at the leading edge via direct interaction. By analogy, in C. elegans the polarity cue provided by the sperm could activate CDC-42 locally and trigger the establishment of polarity (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2003). However, this model is not consistent with the observation that rather than being recruited to the posterior, PAR-6 clears from the posterior in response to the polarity cue (Cuenca et al., 2003; Munro et al., 2004). An alternative model might be that the signal from the centrosome inactivates CDC-42, causing release of PAR-6 from the posterior cortex. Our data are not consistent with this mechanism, since even in the par-6 mutant background the initial clearing of the semi-CRIB mutant proteins occurs. Although this could reflect residual CDC-42 binding activity of the mutant protein, our interpretation is also consistent with direct observations of PAR-6 particles translocating with the actomyosin cytoskeleton (Munro et al., 2004). Our observations of constitutively active GFP∷CDC-42 do not address the question. Although we see a clear enrichment of GFP∷CDC-42 in the anterior that is dependent upon PAR-6, this reporter does not reveal the state of endogenous CDC-42. The best test of the model would be to determine whether endogenous CDC-42 activation state changes locally in response to the polarity cue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Wendy Hoose and Mona Hassab for the technical assistance; members of the Kemphues laboratory, Jun Kelly Liu, Sylvia Lee, Fabio Piano and Anthony Bretscher for the helpful discussions, and M. Gotta and J. Ahringer for the plasmids.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 2 R01 HD027689 to K.K. and Department of Energy GAANN training grant award to D.A.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.002.

References

- Beers M, Kemphues K. Depletion of the co-chaperone CDC-37 reveals two modes of PAR-6 cortical association in C. elegans embryos. Development. 133 doi: 10.1242/dev.02544. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd L, Guo S, Levitan D, Stinchcomb DT, Kemphues KJ. PAR-2 is asymmetrically distributed and promotes association of P granules and PAR-1 with the cortex in C. elegans embryos. Development. 1996;122:3075–3084. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbelo PD, Drechsel D, Hall A. A conserved binding motif defines numerous candidate target proteins for both Cdc42 and Rac GTPases. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:29071–29074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon JL, Labno CM, Bosco G, Seth A, McGavin MH, Siminovitch KA, Rosen MK, Burkhardt JK. Wasp recruitment to the T cell: APC contact site occurs independently of Cdc42 activation. Immunity. 2001;15:249–259. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00178-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeks RJ, Canman JC, Gabriel WN, Meyer N, Strome S, Goldstein B. C. elegans PAR proteins function by mobilizing and stabilizing asymmetrically localized protein complexes. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:851–862. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng NN, Kirby CM, Kemphues KJ. Control of cleavage spindle orientation in Caenorhabditis elegans: the role of the genes par-2 and par-3. Genetics. 1995;139:549–559. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CR, Hyman AA. Asymmetric cell division in C. elegans: cortical polarity and spindle positioning. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004a doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.113823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CR, Hyman AA. Centrosomes direct cell polarity independently of microtubule assembly in C. elegans embryos. Nature. 2004b;431:92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature02825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca AA, Schetter A, Aceto D, Kemphues K, Seydoux G. Polarization of the C. elegans zygote proceeds via distinct establishment and maintenance phases. Development. 2003;130:1255–1265. doi: 10.1242/dev.00284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durfee T, Becherer K, Chen PL, Yeh SH, Yang Y, Kilburn AE, Lee WH, Elledge SJ. The retinoblastoma protein associates with the protein phosphatase type 1 catalytic subunit. Genes Dev. 1993;7:555–569. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etemad-Moghadam B, Guo S, Kemphues KJ. Asymmetrically distributed PAR-3 protein contributes to cell polarity and spindle alignment in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1995;83:743–752. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville S, Hall A. Integrin-mediated activation of Cdc42 controls cell polarity in migrating astrocytes through PKCzeta. Cell. 2001;106:489–498. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville S, Hall A. Rho GTPases in cell biology. Nature. 2002;420:629–635. doi: 10.1038/nature01148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville S, Hall A. Cell polarity: Par6, aPKC and cytoskeletal crosstalk. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003;15:67–72. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrard SM, Capaldo CT, Gao L, Rosen MK, Macara IG, Tomchick DR. Structure of Cdc42 in a complex with the GTPase-binding domain of the cell polarity protein, Par6. EMBO J. 2003;22:1125–1133. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein B, Hird SN. Specification of the anteroposterior axis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1996;122:1467–1474. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotta M, Abraham MC, Ahringer J. CDC-42 controls early cell polarity and spindle orientation in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:482–488. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Kemphues KJ. par-1, a gene required for establishing polarity in C. elegans embryos, encodes a putative Ser/Thr kinase that is asymmetrically distributed. Cell. 1995;81:611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JW, Adami GR, Wei N, Keyomarsi K, Elledge SJ. The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell. 1993;75:805–816. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90499-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung TJ, Kemphues KJ. PAR-6 is a conserved PDZ domain-containing protein that colocalizes with PAR-3 in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Development. 1999;126:127–135. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutterer A, Betschinger J, Petronczki M, Knoblich JA. Sequential roles of Cdc42, Par-6, aPKC, and Lgl in the establishment of epithelial polarity during Drosophila embryogenesis. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:845–854. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James P, Halladay J, Craig EA. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics. 1996;144:1425–1436. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joberty G, Petersen C, Gao L, Macara IG. The cell-polarity protein Par6 links Par3 and atypical protein kinase C to Cdc42. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:531–539. doi: 10.1038/35019573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson A, Driessens M, Aspenstrom P. The mammalian homologue of the Caenorhabditis elegans polarity protein PAR-6 is a binding partner for the Rho GTPases Cdc42 and Rac1. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt. 18):3267–3275. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.18.3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay AJ, Hunter CP. CDC-42 regulates PAR protein localization and function to control cellular and embryonic polarity in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:474–481. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly WG, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Fire A. Distinct requirements for somatic and germline expression of a generally expressed Caernorhabditis elegans gene. Genetics. 1997;146:227–238. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemphues KJ, Priess JR, Morton DG, Cheng NS. Identification of genes required for cytoplasmic localization in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1988;52:311–320. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroschewski R, Hall A, Mellman I. Cdc42 controls secretory and endocytic transport to the basolateral plasma membrane of MDCK cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:8–13. doi: 10.1038/8977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Edwards AS, Fawcett JP, Mbamalu G, Scott JD, Pawson T. A mammalian PAR-3-PAR-6 complex implicated in Cdc42/Rac1 and aPKC signalling and cell polarity. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:540–547. doi: 10.1038/35019582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello CC, Kramer JM, Stinchcomb D, Ambros V. Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 1991;10:3959–3970. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelson D, Silletti J, Murphy G, D’Eustachio P, Rush M, Philips MR. Differential localization of Rho GTPases in live cells: regulation by hypervariable regions and RhoGDI binding. J. Cell Biol. 2001;152:111–126. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton DG, Shakes DC, Nugent S, Dichoso D, Wang W, Golden A, Kemphues KJ. The Caenorhabditis elegans par-5 gene encodes a 14-3-3 protein required for cellular asymmetry in the early embryo. Dev. Biol. 2002;241:47–58. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro E, Nance J, Priess JR. Cortical flows powered by asymmetrical contraction transport PAR proteins to establish and maintain anterior–posterior polarity in the early C. elegans embryo. Dev. Cell. 2004;7:413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nance J, Munro EM, Priess JR. C. elegans PAR-3 and PAR-6 are required for apicobasal asymmetries associated with cell adhesion and gastrulation. Development. 2003;130:5339–5350. doi: 10.1242/dev.00735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S. Intercellular junctions and cellular polarity: the PAR-aPKC complex, a conserved core cassette playing fundamental roles in cell polarity. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001;13:641–648. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellettieri J, Seydoux G. Anterior-posterior polarity in C. elegans and Drosophila — PARallels and differences. Science. 2002;298:1946–1950. doi: 10.1126/science.1072162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praitis V, Casey E, Collar D, Austin J. Creation of low-copy integrated transgenic lines in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2001;157:1217–1226. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.3.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu RG, Abo A, Steven Martin G. A human homolog of the C. elegans polarity determinant Par-6 links Rac and Cdc42 to PKCzeta signaling and cell transformation. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:697–707. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00535-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese KJ, Dunn MA, Waddle JA, Seydoux G. Asymmetric segregation of PIE-1 in C. elegans is mediated by two complementary mechanisms that act through separate PIE-1 protein domains. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:445–455. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman TJ, Sawyer MM, Johnson DI. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cdc42p localizes to cellular membranes and clusters at sites of polarized growth. Eukaryot. Cell. 2002;1:458–468. doi: 10.1128/EC.1.3.458-468.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose LS, Kemphues KJ. Early patterning of the C. elegans embryo. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1998;32:521–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider SQ, Bowerman B. Cell polarity and the cytoskeleton in the Caenorhabditis elegans zygote. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2003;37:221–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.142443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert CM, Lin R, de Vries CJ, Plasterk RH, Priess JR. MEX-5 and MEX-6 function to establish soma/germline asymmetry in early C. elegans embryos. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:671–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severson AF, Bowerman B. Cytokinesis: closing in on the central spindle. Dev. Cell. 2002;2:4–6. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severson AF, Baillie DL, Bowerman B. A Formin homology protein and a profilin are required for cytokinesis and Arp2/3-independent assembly of cortical microfilaments in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:2066–2075. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuse Y, Izumi Y, Piano F, Kemphues KJ, Miwa J, Ohno S. Atypical protein kinase C cooperates with PAR-3 to establish embryonic polarity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1998;125:3607–3614. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.18.3607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons L, Fire A. Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature. 1998;395:854. doi: 10.1038/27579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallenfang MR, Seydoux G. Polarization of the anterior-posterior axis of C. elegans is a microtubule-directed process. Nature. 2000;408:89–92. doi: 10.1038/35040562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts JL, Etemad-Moghadam B, Guo S, Boyd L, Draper BW, Mello CC, Priess JR, Kemphues KJ. par-6, a gene involved in the establishment of asymmetry in early C. elegans embryos, mediates the asymmetric localization of PAR-3. Development. 1996;122:3133–3140. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda S, Oceguera-Yanez F, Kato T, Okamoto M, Yonemura S, Terada Y, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S. Cdc42 and mDia3 regulate microtubule attachment to kinetochores. Nature. 2004;428:767–771. doi: 10.1038/nature02452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziman M, O’Brien JM, Ouellette LA, Church WR, Johnson DI. Mutational analysis of CDC42Sc, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene that encodes a putative GTP-binding protein involved in the control of cell polarity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:3537–3544. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.7.3537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.