Abstract

We work from a stress and life course perspective to consider how stress affects trajectories of change in marital quality over time. Specifically, we ask whether stress is more likely to undermine the quality of marital experiences at different points in the life course. In addition, we ask whether the effects of adult stress on marital quality depend on childhood family stress experiences. Growth curve analysis of data from a national longitudinal survey (Americans’ Changing Lives, N = 1,059 married individuals) reveals no evidence of age differences in the effects of adult stress on subsequent trajectories of change in marital experiences. Our results, however, suggest that the effects of adult stress on marital quality may depend on childhood stress exposure. Stress in adulthood appears to take a cumulative toll on marriage over time—but this toll is paid primarily by individuals who report a more stressful childhood. This toll does not depend on the timing of stress in the adult life course.

Keywords: childhood stress, cumulative disadvantage, life course, marital quality, stress

Although recent research demonstrates that, on average, marriages tend to decline in quality over time (e.g., Umberson, Williams, Powers, Chen, & Campbell, 2005; VanLaningham, Johnson, & Amato, 2001), most theories of marital quality work from the assumption that some marriages are more likely than others to deteriorate (Bradbury & Karney, 2004). A number of studies suggest that exposure to stress may contribute to marital quality decline (e.g., Cohan & Bradbury, 1997). We know little, however, about how ephemeral or lasting these stress effects are or which marriages are most vulnerable to stress. The effects of stress on marital quality may be ephemeral for some marriages, long lasting for others, and largely neutral for still others. Moreover, marital quality may be more vulnerable to stress at specific points in the life course.

Recent theoretical work merges the life course perspective with a stress model to consider how stress shapes individual outcomes over the life course (Pearlin & Skaff, 1996). According to the life course perspective on stress, individual lives follow unique trajectories of change over time, and these trajectories are shaped by social context as well as the occurrence, timing, and sequencing of stressful events and situations (Wheaton & Gotlib, 1997). We work from this stress and life course perspective to view the marital quality of individuals as following a developmental trajectory over time, experiencing ups and downs as well as periods of stability and calm. We hypothesize that these individual trajectories are altered by exposure to stress. Life course theory suggests that marital quality may be more vulnerable to stress at certain points in the adult life course. The life course perspective also recognizes that childhood experiences have enduring effects over the life course (Wheaton & Clarke, 2003), and we examine whether the effects of adult stress exposure on marital quality depend on reports of childhood stress exposure.

Our goal is to add to life course research on stress and marital quality in three ways that reflect our theoretical perspective. First, we rely on a national longitudinal survey of individuals aged 24–96 years to consider how a measure of stress in adulthood contributes to marital quality and whether the effect of stress on marital quality depends on age of the respondent. This allows us to examine whether stress has stronger effects on marital quality at different points in the adult life course. Second, we take a broad view of the life course and consider how stress exposure in childhood may affect marital quality in adulthood, particularly in response to stress in adulthood. Third, we use growth curve analysis to correspond to our conceptualization of individual marriages as having their own developmental trajectories. This method is uniquely suited to a life course analysis of stress and marital quality over time, allowing us to incorporate baseline levels of marital quality as well as trajectories of change in marital quality over time and in relation to stress. This approach sheds light on how slowly or quickly marital quality changes in response to stress and for different groups of individuals.

Background

A Stress and Life Course Perspective

Until quite recently, stress research and life course research were largely separate entities (Elder, George, & Shanahan, 1996), but as Pearlin and Skaff (1996) emphasize, there is a “natural alliance” between these two perspectives:

…an understanding of the stress process can contribute to the understanding of life course trajectories and, conversely, life course perspectives provide vantage points for the examination of stress processes and their variations. (p. 239)

In addition, there is a lengthy tradition of research on life course change in marital quality (e.g., Umberson et al., 2005; VanLaningham et al., 2001), and a number of studies focus on the impact of stress on marital quality (see a review in Bradbury, Fincham, & Beach, 2000). These two bodies of research, however, are largely separate. We use an integrated stress and life course perspective to consider how marital quality and stress may be linked over the life course.

Stress and the Life Course

Traditionally, stress researchers have distinguished between exposure to stressful life events and chronic sources of stress (George & Lynch, 2003; Turner, Wheaton, & Lloyd, 1995). A stressful life event refers to an undesirable event that occurs at a specific point in time (e.g., death of a loved one), whereas chronic stress refers to ongoing sources of stress (e.g., ongoing financial stress). Chronic stressors may follow from stressful life events and may lead to a buildup of stress or stress proliferation (Pearlin, Aneshensel, & LeBlanc, 1997). For example, unemployment, a stressful event, may lead to a number of chronic stressors (e.g., financial strain). Any particular individual is characterized by an overall level of stress burden at any given time, and overall burden involves the accumulation of chronic stressors and life events that one faces (Turner et al.).

Leading stress researchers now emphasize that life events and chronic stressors should be jointly considered in investigations of stress and individual outcomes (Turner et al., 1995). Moreover, Turner and colleagues (Turner & Avison, 2003; Turner et al.) suggest that major traumatic events occurring over one’s lifetime (e.g., divorce of parents during childhood) should be added to measures of cumulative stress burden. In the present study, we view adult stress burden as a function of recent stressful life events as well as chronic stressors. We consider childhood stress separately from adult stress for theoretical reasons linked to our focus on marital quality (see also Wheaton & Clarke, 2003).

Stress in adulthood

Research indicates that stress exposure may be greater in young adulthood than in middle adulthood (e.g., Turner et al., 1995), and several studies suggest that the prevalence of stressful life events may diminish after midlife and into old age (Ensel, Peek, Lin, & Lai, 1996). Pearlin and Skaff (1996), however, argue that this may be an artifact of measurement in that most life event inventories tend to overrepresent stressors that older people are less likely to experience, for example, marriage, divorce, job changes, and having children. These sorts of stressors are more likely to occur earlier in the life course, whereas other events (e.g., the death of a loved one) and chronic strains (e.g., health problems of self or spouse) are more likely to occur later in the life course (Ensel et al., 1996; Hughes, Blazer, & George, 1988). Thus, life course research on stress should consider a range of life events and chronic stressors that vary in prevalence across the adult life course.

Stress and marital quality

It is fairly well established that certain stressful life events and chronic strains are inversely associated with marital quality. For example, the death of a parent (Umberson, 1995), job loss (Lorenz, Conger, Simon, Whitbeck, & Elder, 1991), becoming a parent (Belsky, Lang, & Rovine, 1985), childrearing stress (Helms-Erickson, 2001), and chronic financial strain (Bradbury et al., 2000) have been associated with reduced marital quality. A few longitudinal studies following newlywed couples suggest that cumulative negative life events are also associated with lower marital quality over time (Cohan & Bradbury, 1997; also see a review in Bradbury & Karney, 2004).

Although a number of studies acknowledge that stress may affect marital quality, little attention has been directed to the possibility that the effects of stress on marital quality may depend on life course position (Bradbury et al., 2000). We are aware of no studies that consider how overall stress might affect marital quality over the life course. There are at least two reasons to think that stress would undermine marital quality more for younger than for older couples. First, some studies suggest that marital quality declines most rapidly in the early years of marriage (VanLaningham et al., 2001). If this is the case, then the marriages of young adults may be more vulnerable, thus more adversely affected by stress, than are those of older adults. Second, Carstensen, Levenson, and Gottman (1995) have developed an emotional reactivity theory to suggest that husbands and wives react to one another differently as they age, in ways that may be beneficial to marriage. This theory suggests that individuals become less emotionally reactive to relationship difficulties as they age. If this finding is supported over the adult life span, then stress may be less likely to adversely affect the marital quality of older adults.

Childhood stress

Early life course experiences shape later life outcomes (McLeod, 1991; McLeod & Kaiser, 2004; Sobolewski & Amato, 2005). Childhood stress may affect eventual marital quality in several ways. Childhood stress could have a selection effect, influencing the type of partner one chooses or the initial quality of one’s marriage. Family systems theory suggests that stressful childhood family experiences adversely affect adult attachments (see a review in Karney & Bradbury, 1995). Supporting this view, several studies report adverse effects of childhood stress on marital adjustment (e.g., Sabatelli & Bartle-Haring, 2003). In addition, individuals who experienced high levels of childhood stress may be more vulnerable to stress that occurs in adulthood (Wheaton & Clarke, 2003). If the latter occurs, then those who experienced stressful childhood environments may react more strongly to stress in adulthood, and this, in effect, would magnify the impact of adult stress on marital quality.

Trajectories of change over the life course

The life course perspective emphasizes that individuals continue to develop and change over time. Moreover, trajectories of change are likely to depend on childhood experiences, one’s current position in the life course, and exposure to recent and ongoing stress. Growth curve analysis is ideally suited to analyzing trajectories of change in marital quality over time. This approach allows us to consider the marital quality of individuals at the beginning of the study as well as their rate of change in marital quality over time. The rate of change might be slower or faster for different groups (e.g., different age groups, those who experienced substantial childhood family stress and those who did not). Levels of stress burden may also change over time. We estimate models that consider whether change in levels of stress burden is associated with changes in marital quality over time. Growth curve analysis then provides a dynamic assessment of individual trajectories of marital quality over time, and as a function of recent, ongoing, and childhood stress exposure.

Age and Other Covariates

Several sociodemographic variables are associated with marital quality and are included as covariates in analyses. Age is positively associated with marital quality, and the rate of decline in marital quality is more rapid at younger ages (Umberson et al., 2005). Although race and gender differences in the rate of decline in marital quality over time are not significant, men tend to report higher levels of marital quality than women, and African Americans report lower levels of marital quality than non-Hispanic Whites (Umberson et al., 2005; VanLaningham et al., 2001). Socioeconomic status shapes the marital context but is less consistently associated with marital quality (Clark-Nicolas & Gray-Little, 1991). Selection bias is also a potential issue in studies of marital quality because low-quality marriages may be more likely to be removed from the population over time (because of divorce), leaving higher quality marriages at older ages. In an effort to address this issue, we include a control variable in analyses to indicate whether the individual has been in a previous marriage as well as a Heckman-type correction that addresses the propensity for divorce/separation.

The Present Study

In the present study, we adopt a life course perspective to consider how stress shapes levels of marital quality and trajectories of change in marital quality over time. We address the following questions:

How does stress burden in adulthood affect trajectories of change in the quality of marital experiences over time? Does the effect of adult stress burden on marital trajectories depend on age of the respondent?

Does the effect of adult stress burden on marital trajectories depend on reports of childhood stress exposure? Do these effects further depend on age of the respondent?

Method

Data

We use three waves of data from the Americans’ Changing Lives panel survey of individuals in the contiguous United States (House, 1986). The original sample (aged 24–96 years in 1986) was obtained using multistage stratified area probability sampling, with an oversample of African Americans, persons older than 59 years, and married women whose husbands were older than 64 years in 1986. Face-to-face interviews lasting approximately 90 minutes each were conducted with individuals in 1986 (N = 3,617), 1989 (N = 2,867), and 1994 (N = 2,398).

In 1986, 1,904 married individuals (not married to one another) who were either non-Hispanic White or African American were interviewed. Seventy-one percent (n = 1,352) of these individuals were interviewed in all three waves of data collection, whereas 11.4% (n = 217) died by 1994 and the rest (17.6%, n = 335) did not respond to one or both of the follow-up surveys. Of the 1,352 individuals who were interviewed at all three time points, 78.3% (n = 1,059) remained married to the same spouse over the 8-year period, 8.4% (n = 113) divorced, 12.1% (n = 164) were widowed, and 1.2% (n = 16) were separated without divorcing during this period.

In this study, we look at the 1,059 individuals who were continuously married across the three waves of data collection and who are either non-Hispanic White or African American (too few cases were available to assess other racial/ethnic groups). To assess the effects of stress on marital quality, we limit our analyses to continuously married individuals only. Of these individuals, 182 were in a second or later marriage in 1986. All analyses include a control variable indicating whether the individual is in a first- or higher order marriage. Missing data on marital quality and childhood stress reduced the cases in the sample to 1,002 for the measure of positive marital experience and 984 for the measure of negative marital experience. In the present study, change over time refers to change over the 8-year study period.

Measures

Marital quality

Marital relationship research has not relied on a standard approach to measuring marital quality (Fincham & Bradbury, 1987; Glenn, 1990). Our approach to measuring marital quality is driven by both conceptual and empirical concerns. Conceptually, previous research shows that a distinction should be made between positive and negative dimensions of marital relationships as they have different correlates (Bradbury et al., 2000). In addition, growth curve analysis requires at least three data points, and we are limited to measures that were collected at each of the three interviews.

We derived our measures of positive and negative marital experiences by using several approaches (e.g., using different numbers of factors with different rotation methods or different samples) to examine various marital quality factors. The factor analyses revealed two latent constructs that we label positive marital experience and negative marital experience. Scales were created so that higher values indicate higher levels of the intended construct. The correlations between the two marital quality dimensions are −.603, −.634, and −.676 at the three time points. To ensure that change over time reflects growth rather than change in the measurement scale, the scales for each indicator at each wave of measurement are standardized using the Time 1 mean and standard deviation (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1987). To help ensure the comparability of the latent constructs of marital quality over time, the factor loadings are constrained to be equal across waves. In addition, to ensure that the latent construct of marital quality is the same from model to model, the same sets of estimated parameter coefficients for the measurement model from the model without covariates are used for further analyses with covariates. All the factor loading estimates are statistically significant (and are presented in parentheses below). Marital quality measures were centered at their means. Mplus software was used to estimate our models.

Positive marital experience is a latent variable composed of four items. The first item, marital satisfaction (factor loading = 1.000), is based on responses to the question, “How satisfied are you with your marriage?” The response categories range from 1 = not at all satisfied to 5 = completely satisfied. The second (factor loading = 1.178) and third (factor loading = .876) items are based on responses to the questions (a) “How much does your (husband/wife) make you feel loved and cared for?” and (b) “How much is (he/she) willing to listen when you need to talk about your worries or problems?” Response categories for both the items range from 1 = not at all to 5 = a great deal. The fourth item (factor loading = .456) considers whether one’s spouse is a person with whom the respondent can really share very private feelings and concerns (0 = no, 1 = yes). Factor determinancy coefficients indicate the quality of the factor score estimates as follows: .919 for Time 1, .930 for Time 2, and .930 for Time 3 (see Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2004).

Negative marital experience is a latent variable measured with two items. First (factor loading = 1.000), respondents were asked, “How often do you feel bothered or upset by your marriage?” Categories range from 1 = never to 5 = almost always. Second (factor loading = 1.557), respondents were asked, “How often would you say the two of you typically have unpleasant disagreements or conflicts?” Response categories range from 1 = never to 7 = daily or almost daily. Factor determinancy coefficients are .817 at Time 1, .778 at Time 2, and .815 at Time 3. Both the measures are based on the same items across the three waves of data collection.

Although we assess a positive and a negative dimension of marital experience, we do not measure all aspects of marital quality (e.g., marital stability, various global assessments) (see Fincham & Bradbury, 1987). In addition, some of our items may confound evaluative judgments with reports of behavior. We are limited in the number of items we have available to measure our major constructs, particularly negative marital experiences, making it more likely that we are omitting some features of this construct. Ideally, studies would include extensive measures of multiple dimensions of marital quality, collected at multiple data points.

Stress burden in adulthood

Leading stress researchers emphasize the importance of considering stressful life events and chronic sources of stress in one measure of cumulative stress burden (Turner et al., 1995). Turner et al. review evidence that reports of life events, even those distant in time, are reliable and valid measures of actual life events. One concern is that self-reports of chronic stress are inherently biased because of their subjective nature. Yet, previous research shows a strong relationship between subjective measures of stress (e.g., financial strain) and more objective indicators (e.g., socioeconomic status) (Wheaton, 1994), and that such measures are not significantly distorted by changes in psychological distress over time (Schraedley, Turner, & Gotlib, 2002). Moreover, reports of chronic stress constitute important conceptual information on overall stress burden:

The advantage of using subjective reports of chronic stress is that they allow shorthand reference to an array of possible objective social realities that would be impractical to measure directly, and more importantly, they typically reflect realities that most would consider objectively stressful. (Turner et al., 1995, p. 108)

To understand the influence of adult stress burden on marital quality, we include a variable measuring stress burden in adulthood. Our stress burden measure reflects seven recent life events and five potential sources of chronic stress in various life domains. We consider significant life events that occurred in the 3 years prior to Time 1 and in the periods between subsequent data collections: death of a significant other, provide or arrange care for impaired person, involuntary job loss, birth of a child, residential move, life threatening illness or injury, and death of a parent. We consider whether study participants experienced ongoing stress in the following domains: parental role, finances, job, health, and care provider strain. Certainly, we have not included all possible sources of stress across the life course; however, we have chosen several of the most common sources of stress for our overall stress measure. Because stress burden may fluctuate over time, we also analyze the effect of the changing rate of adult stress burden on marital experiences over time.

Death of a significant other includes the death of a child, close friend, or other relative. Provide or arrange care refers to care provided or arranged for any impaired friend or relative. Involuntary job loss measures whether the respondent involuntarily lost a job for reasons other than retirement. Residential move refers to moving to a new residence. Respondents were asked whether they experienced the health event of a life threatening illness or accidental injury. Birth of a child is indicated by the presence of a child younger than 3 years in the household at Time 1 or the birth of a child between subsequent waves. Death of a parent refers to the death of a mother or a father.

Parental role stress is measured with three items that tap into overall satisfaction with being a parent, frequency of feeling upset or bothered as a parent, and degree of happiness with the way children have turned out to this point (α= .63 at Time 1; α = .68 at Time 2; α = .66 at Time 3). Financial stress comprises three items including difficulty meeting monthly payments on bills, how well finances usually work out at the end of the month (some left over, just enough, not enough to make ends meet), and satisfaction with present financial situation (α = .77 at Time 1; α = .80 at Time 2; α = .73 at Time 3). Job stress refers to the frequency of feeling bothered or upset at work. Health-related stress refers to self-rated health (higher value indicates poorer health). Care provider stress refers to how stressful it is to provide/arrange care for an impaired friend or relative.

In creating the stress burden measure, we first dichotomized all life event variables. These measures are coded 1 to reflect whether the life event occurred in the 3 years prior to the Time 1 interview or in the periods between subsequent data collections and 0 if the event did not occur during that time period. Next, we standardized the life event variables and the chronic stress variables. We then summed the standardized life event variables and the standardized chronic stress variables. Standardization ensures that the measures are weighted equally (see Turner et al., 1995). The final adult stress burden measure is standardized and has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 at each wave. Adult stress burden (at Time 1) exhibits a modest decline with advancing age, and this general pattern is not significantly different for men and women. At Time 1, 147 (14.7%) respondents scored one standard deviation or more below the mean on stress burden and 178 (17.8%) respondents scored one standard deviation or more above the mean.

Reports of childhood stress exposure

Respondents reported on the occurrence of seven family-related stressors that occurred at age 16 years or younger: at least one parent died, parents divorced, parents had marital problems, at least one parent had a mental health problem, at least one parent had an alcohol problem, never knew father, and family economic hardship. Family economic hardship is coded 1 for those respondents who report that their family was somewhat worse off or a lot worse off than the average family in their community. Each of the other childhood stressors was coded 0 if it did not occur and 1 if it did occur, and scores on all these dichotomous variables were summed to create an indicator of the number of childhood stressors experienced. The measure of childhood stress exposure ranges from 0 to 5, with a mean of .70 and a standard deviation of 1.01. Five hundred eighty-eight (58.7%) individuals reported the minimum value of childhood stress (labeled low), and 200 (20.0%) individuals scored one standard deviation or more above the mean (labeled high) on this measure. Among the individuals reporting high childhood stress, 146 (14.6%) reported minimal change (within 1 SD of zero) in adult stress burden over time, 33 (3.3%) reported a decreasing rate of adult stress burden over time (scoring 1 SD or more below the mean on the changing rate of stress), and 20 (2.0%) reported an increasing rate of adult stress over time (scoring 1 SD or more above the mean).

The childhood stress exposure items may be subject to bias associated with retrospective recall. Several studies on mental health outcomes provide empirical evidence of the reliability and validity of retrospective reports of death or divorce of parent (Robins et al., 1985; see a review in McLeod, 1991). Schraedley et al. (2002) find that depression in adulthood distorted recall of past depressive symptoms and past traumatic events. Depression in adulthood did not, however, alter the reporting of parental psychopathology (i.e., parents’ depression and substance abuse), two measures that we include in our index of reported childhood stress exposure. Although we emphasize that our measure of childhood stress exposure is limited by retrospective reports, these previous studies provide some support for the validity and reliability of such reports. Moreover, a growing body of evidence points to the importance of childhood experiences in shaping adult outcomes (McLeod; McLeod & Kaiser, 2004; Sobolewski & Amato, 2005). In addition, our data are limited because we do not have information on the age at which a child experienced each of the life events considered. We assess only those events that were reported to have occurred at age 16 years or younger. Although previous research suggests that this may be an important age cut-point in terms of effects on adult outcomes (McLeod & Kaiser), we are unable to assess how specific effects are related to the timing of events in childhood. Until prospective studies are able to follow individuals from early childhood throughout late adulthood, the evidence linking childhood and later life experiences will remain speculative.

Life course and sociodemographic variables

Our primary proxy for life course position is age of the respondent, measured in years. All models are adjusted for the effect of additional sociodemographic characteristics that may be associated with marital quality, including gender (0 = female, 1 = male), race (0 = Other, 1 = African American), education (number of years completed), and total family income in 1986 ($1,000s). Table 1 presents means and standard deviations for all variables in the analysis. For each of the interpretations, household income is measured in single dollars (Table 1). In all the subsequent models, household income is measured in increments of $1,000 and all continuous independent variables such as age, education, and family income are centered at their means.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations for all variables in the analysis (N = 1,002)

| Variable | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Stress measures | ||

| Adult stress burden at Time 1 | −.00 | 1.00 |

| Adult stress burden at Time 2 | −.00 | 1.00 |

| Adult stress burden at Time 3 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Childhood stress exposure | 0.70 | 1.01 |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Age | 49.36 | 14.57 |

| Gender (1 = male) | .46 | .50 |

| Race (1 = African American) | .19 | .39 |

| Education (years) | 12.56 | 2.93 |

| Household income ($1,000s) | 35.88 | 24.58 |

| Previous divorce | .18 | .38 |

| Marital quality measures | ||

| Positive marital experiences at Time 1 | −.00 | .72 |

| Positive marital experiences at Time 2 | −.09 | .77 |

| Positive marital experiences at Time 3 | −.10 | .82 |

| Negative marital experiences at Time 1 | −.03 | .52 |

| Negative marital experiences at Time 2 | .03 | .54 |

| Negative marital experiences at Time 3 | .11 | .54 |

| Divorce/separate hazard | −.16 | .18 |

Selection Bias

A potential problem in an analysis of marital quality over time is the possibility of selection bias because of divorce. It may be that the marriages most likely to be adversely affected by stress are the same marriages that are most likely to end in divorce and drop out of the study. As a result, any estimates of the effects of stress on marital quality may be biased because we are following only higher quality marriages among individuals of older ages. This type of nonrandom selectivity can lead to biased estimates of the effects of independent variables on marital quality. We are unable to fully address the possibility of selection bias in the present study, but we begin to address this issue in two ways. First, we include a control variable for previous divorce in our analyses in an effort to partially account for one’s propensity for divorce (1 = previous divorce, 0 = no previous divorce).

Second, we estimated sample selection models to investigate possible bias in the effects of independent variables on marital quality as a result of unmeasured heterogeneity. We adopt the approach developed by Heckman (1979) that consists of first modeling the probability that a respondent is in a marriage at Wave 1 (relying on the complete data set of married and unmarried individuals), conditional on a set of predictors measured at earlier waves (number of previous marriages, age at marriage, teenager when married, high financial strain, employment of wife, stepchild in the home, marital duration, recent thoughts of divorce, spouse has done things respondent can never forgive, African American, and years of education) (White, 1990). Then, for the sample of married individuals, marital quality is modeled as a function of a set of independent variables, including the estimated risk of staying married from the first stage. This specification begins to control for sample selection and provides additional information about the degree of selectivity. After this correction, estimates of covariate effects on marital quality should be interpreted as having been adjusted for the observed and unobserved variables that affect both the propensity to remain married and the level of marital quality.

Analytical Design

Growth curve analysis

We use latent linear growth models to assess the effects of independent variables on initial levels and change in marital quality constructs. Thus, our models not only account for the effects of independent variables on the conditional mean levels of marital quality but also account for effects on the rate of change in marital quality over time. The growth parameters can be viewed as time-invariant random variables that vary by individual and depend on a set of fixed and time-varying covariates. Structural parameters from this part of the model provide the basis for assessing effects of key variables on level and change in marital quality.

Our models further involve joint estimation of the latent growth curve model described above and a measurement model that relates multiple indicators of marital quality to a wave-specific marital quality factor. These are combined into a single model referred to as a multiple indicator linear growth model (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2004, p. 219). Specifically, each wave of data yields measurements of multiple marital quality items, which are hypothesized to be indicators of a wave-specific latent factor. These factors, in turn, are treated as dependent variables in the latent growth curve model.

Results

Results from growth curve models with no covariates (not shown) indicate that positive and negative marital experiences change over the 8-year study period. Positive marital experiences generally decreased over the 8-year period (b =−.012; p ≤ .001) and negative marital experiences increased (b = .017; p ≤ .001). We also find evidence of variation in the random intercept for both measures (var(IPI) =.436 and var(INI) =.224; p ≤ .001), with modest variation in random slopes (var(SPI) =.002 and var(SNI) =.001; p ≤ .05). The covariance parameters are statistically 0 and hence provide no evidence of dependence in growth parameters (i.e., that changes in positive or negative experiences occur at a faster, or slower, rate for individuals who are high, or low, on the marital experience measures).

Adult Stress Burden and Marital Experiences

Growth curve techniques allow us to consider that individuals start the study with different levels of positive and negative marital experience and that they may experience different rates of change in positive and negative marital content over time and as a function of stress burden. The latent intercept and slope are the quantities of primary interest in growth curve models. Table 2 presents the estimated effects of the stress measures and the other independent variables on the initial level, or the latent intercept, of positive and negative marital experiences as well as the rate of change, or the latent slope, in positive and negative marital experiences over time.

Table 2.

Effect of adult stress burden and childhood stress on change in marital quality from linear growth curve models, 1986–1994 (N = 1,002/984)

| Positive Marital Experiences | Negative Marital Experiences | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | |

| Adult stress burden, initial level | −0.288*** | −0.001 | 0.245*** | 0.001 |

| Changing rate of adult stress burden | — | −0.310 | — | 0.199 |

| Childhood stress | −0.041 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Age | −0.016*** | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Gender (1 = male) | 0.301*** | −0.001 | −0.073* | 0.000 |

| Race (1 = African American) | −0.097 | −0.010 | 0.043 | −0.003 |

| Education | −0.009 | 0.001 | 0.015* | 0.000 |

| Household income ($1,000s) | −0.003** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Previous divorce | 0.233*** | −0.033*** | −0.140** | 0.029*** |

| Divorce/separate hazard | 1.470*** | −0.035 | −0.691*** | 0.054* |

| Means of growth parameters | 0.082 | −0.010 | −0.085* | 0.019*** |

| Variances in growth parameters | 0.331*** | 0.002 | 0.174*** | 0.001 |

| Model Fit Index | ||||

| Number of free parameters | 63 | 56 | ||

| Log likelihood | −31979.460 | −24545.361 | ||

| AIC | 64084.920 | 49202.721 | ||

| BIC | 64394.235 | 49476.652 | ||

Note: AIC = Akaike Information Criteria. BIC = Bayesian Information Criteria.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 2 indicates that adult stress burden, measured at the beginning of the study period, is associated with initial levels of both positive and negative marital experiences. Values for the latent intercept (shown in Table 2) show that higher levels of initial stress burden are associated with significantly lower initial levels of positive marital experience and significantly higher initial levels of negative marital experience. Yet, initial adult stress burden does not affect how quickly or slowly positive and negative marital experiences change over the subsequent 8-year period (indicated by values for the latent slope shown in Table 2).

Because levels of adult stress burden may change over time (either up or down), we included a variable for the changing rate of stress over the 8-year study period. As shown in Table 2, the changing rate of stress burden is not significantly associated with the rate of change in positive or negative marital experiences. These results suggest that fluctuations in stress burden do not have consequences for the rate of change in marital experiences over time. A life course and stress perspective, however, suggests that some marriages will be more vulnerable than others in response to changing levels of stress. This perspective suggests two hypotheses. We first test the hypothesis that stress has more adverse effects on the marriages of younger individuals. Second, we assess the possibility that childhood family stress experiences may increase the influence of adult stress burden on marital experiences.

Age Differences in the Effects of Stress

We tested the hypothesis that stress would lead to change in marital experiences more for younger compared to older respondents by assessing interactions of age with the stress measures in predicting marital outcomes. The results, including only those interactions that are statistically significant, are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Effect of adult stress burden and childhood stress on change in marital quality from linear growth curve models, with age interactions, 1986–1994 (N = 1,002/984)

| Positive Marital Experiences | Negative Marital Experiences | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | |

| Adult stress burden, initial level | −0.285*** | 0.004 | 0.231*** | −0.001 |

| Changing rate of adult stress burden | — | −0.226 | — | 0.152* |

| Childhood stress | −0.051 | −0.001 | 0.011 | 0.003 |

| Age × Initial Level of Adult Stress Burden | −0.008** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Age × Changing Rate of Adult Stress Burden | — | 0.005 | — | 0.002 |

| Age × Childhood Stress | −0.002 | 0.000 | 0.003* | 0.000 |

| Age | −0.016*** | 0.001* | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Gender (1 = male) | 0.290*** | 0.001 | −0.067 | −0.001 |

| Race (1 = African American) | −0.113 | −0.008 | 0.062 | −0.004 |

| Education | −0.010 | 0.001 | 0.016* | 0.000 |

| Household income ($1,000s) | −0.002 | 0.000 | −0.001 | 0.000 |

| Previous divorce | 0.246*** | −0.030*** | −0.134* | 0.028*** |

| Divorce/separate hazard | 1.627*** | −0.020 | −0.763*** | 0.047* |

| Means of growth parameters | 0.099* | −0.008 | −0.108** | 0.018*** |

| Variances in growth parameters | 0.325*** | 0.002 | 0.173*** | 0.001 |

| Model Fit Index | ||||

| Number of free parameters | 52 | 45 | ||

| Log likelihood | −18667.277 | −11494.194 | ||

| AIC | 37438.555 | 23078.388 | ||

| BIC | 37693.862 | 23298.511 | ||

Note: AIC = Akaike Information Criteria. BIC = Bayesian Information Criteria.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

In Table 3, the model for positive marital experiences shows only one significant age interaction. Age interacts with initial adult stress burden in predicting initial levels of positive marital experiences. Contrary to our hypothesis, this interaction suggests that initial levels of adult stress burden are more strongly associated with lower levels of positive experiences for older people than for younger people. Table 3 also reveals a significant interaction of age with childhood stress in predicting initial levels of negative marital experiences. This interaction suggests that reports of childhood stress are more strongly associated with initial levels of negative marital experiences for adults at older ages.

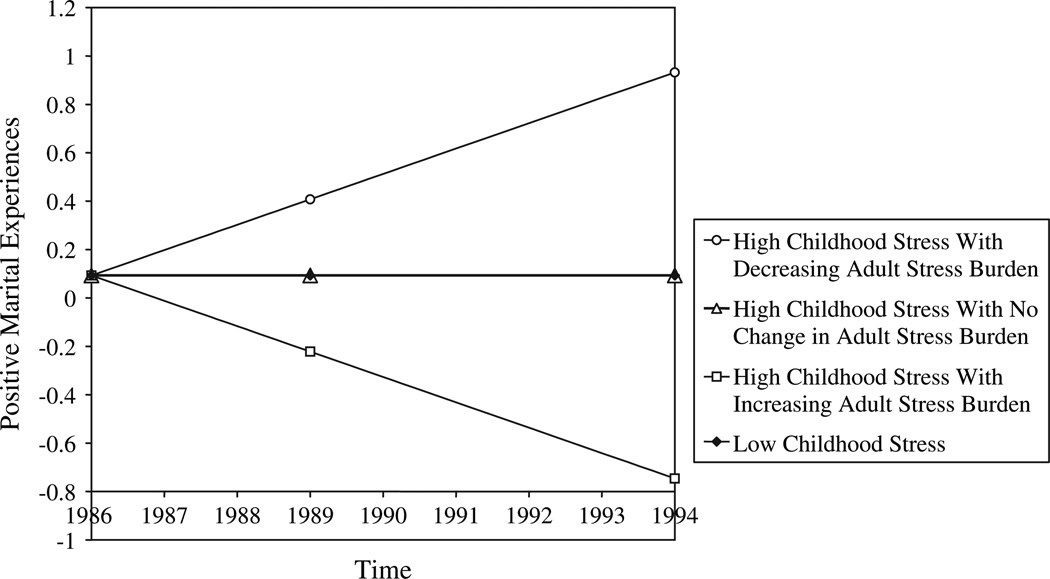

Childhood Family Stress

We now consider how childhood family stress might shape the effect of adult stress burden on marital experiences. The final results presented in Table 4, including only the significant age interactions as well as the interaction of the changing rate of adult stress burden with childhood stress, reveal a significant interaction between reports of childhood stress and the changing rate of adult stress burden in affecting the rate of change in positive marital experiences (the estimated effect on negative marital experience is not statistically significant). This interaction effect is illustrated in Figure 1 where we present predicted trajectories of change in positive marital experiences by level of reported childhood stress and changing stress levels in adulthood. Figure 1 suggests that changes in adult stress burden do not modify the trajectory of change in positive marital experiences for those individuals who report low childhood stress. But the marital trajectories of individuals who report high levels of childhood stress (1 SD or more above the mean) seem to be more reactive to stress burden in adulthood. Among the high–childhood stress groups, the predicted positive marital experience trajectory of those reporting no change in adult stress burden is similar to that reported by the low–childhood stress group. An increasing rate of adult stress is associated with a modest decline in positive marital experiences for those who report high levels of childhood stress, whereas a decreasing rate of stress in adulthood is associated with a modest increase in positive marital experiences for this group. These findings suggest that individuals exposed to high levels of childhood stress may be more reactive to fluctuations in adult stress burden—in both positive and negative directions.

Table 4.

Effect of adult stress burden and childhood stress on change in marital quality from linear growth curve models with interaction of childhood stress and changing rate of adult stress burden, 1986–1994 (N = 1,002/984)

| Positive Marital Experiences | Negative Marital Experiences | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | |

| Adult stress burden, initial level | −0.297*** | 0.004 | 0.236*** | −0.001 |

| Changing rate of adult stress burden | — | −0.049 | — | 0.092 |

| Childhood stress | −0.046 | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.144 |

| Age × Initial Level of Adult Stress Burden | −0.009*** | — | — | — |

| Age × Childhood Stress | — | — | 0.003** | — |

| Childhood Stress × Changing Rate of Adult Stress Burden | — | −0.424** | — | 0.142 |

| Age | −0.017*** | 0.001*** | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Gender (1 = male) | 0.289*** | 0.001 | −0.067 | 0.000 |

| Race (1 = African American) | −0.116 | −0.007 | 0.061 | −0.003 |

| Education | −0.010 | 0.001 | 0.016* | 0.000 |

| Household income ($1,000s) | −0.002 | 0.000 | −0.001 | 0.000 |

| Previous divorce | 0.247*** | −0.032*** | −0.134* | 0.028*** |

| Divorce/separate hazard | 1.618*** | −0.034 | −0.768*** | 0.050* |

| Means of growth parameters | 0.093* | −0.010 | −0.108** | 0.110 |

| Variances in growth parameters | 0.323*** | 0.001 | 0.172*** | 0.001 |

| Model Fit Index | ||||

| Number of free parameters | 49 | 42 | ||

| Log likelihood | −18651.075 | −11492.468 | ||

| AIC | 37400.150 | 23068.936 | ||

| BIC | 37640.728 | 23274.384 | ||

Note: AIC = Akaike Information Criteria. BIC = Bayesian Information Criteria.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Predicted trajectories of positive marital experience by reports of childhood family stress and changing rate of adult stress burden (N = 1,002)

Covariates in the Model

The full model in Table 4 shows that a number of covariates are associated with marital experiences. These results are consistent with previous research on marital quality and marital quality change (Umberson et al., 2005; VanLaningham et al., 2001). Age is associated with lower initial levels of positive marital experiences, but the rate of decline in positive marital experiences occurs at a slower pace for older people. Men report higher initial levels of positive experiences than women. Education is positively associated with initial levels of negative experiences.

The hazard term for divorce/separation and having had a previous divorce are significantly associated with positive and negative marital experiences. It appears that the rate of increase in negative marital experiences is more rapid for those with a higher risk for divorce. Although this suggests that selectivity is operative, the estimates and standard errors in the substantive equations are of about the same magnitude as those from models that do not control for selectivity. This gives us confidence that selection bias does not undermine the quality of the estimates in our final models. The finding that higher risk for divorce (the divorce hazard term) is associated with lower initial levels of negative marital experiences and higher initial levels of positive marital experiences seems counterintuitive, but we suspect this reflects a pattern, whereby lower commitment and initially high evaluations of and expectations for marriage increase the risk of divorce (Amato & DeBoer, 2001).

Discussion

Marital quality scholars emphasize that some marriages are more vulnerable than others over the course of time (Bradbury & Karney, 2004). The life course perspective directs attention to developmental processes over the life course and points to the importance of considering how stress burden at different points in the life course might lead some marriages to be more vulnerable to stress (Wheaton & Clarke, 2003). Building on the theoretical work of Carstensen et al. (1995), we hypothesized that stress would have stronger effects on the marriages of younger individuals; however, our results do not support this hypothesis. Although we find some age differences in the effects of stress on initial levels of positive and negative marital content, these results are cross-sectional in nature. Moreover, the longitudinal results did not reveal any significant age differences in the rate of change in marital experiences in response to stress. Given the constraints of our data and possible underestimation of effects, we cannot close the book on the question of age differences in the effects of stress on marriages. The present results, however, do not provide evidence of greater vulnerability for younger people. It may be that stress is difficult for marriage regardless of when it occurs. Future research, both quantitative and qualitative, should further explore how age and developmental change might modify the impact of stress on marital quality.

In the second part of our analysis, we build on the stress and life course perspective by asking whether stress that occurred early in the life course might shape the effects of adult stress burden on marital experiences. Our results suggest that stress in adulthood takes a cumulative toll on marriage over time, but this toll is paid primarily by those individuals who recall more stressful childhoods. First, reports of higher childhood stress are associated with poorer starting points on positive and negative marital content. Second, marital quality may be more volatile for those individuals who grew up with high levels of family stress. We find that, among those individuals who report low levels of childhood family stress, fluctuations in adult stress burden have little effect on positive marital experiences. Changing levels of adult stress, however, are associated with change in marital quality for those adults who report high levels of childhood family stress. Within this latter group, increasing levels of adult stress are associated with a moderate decline in positive marital experiences over time and decreasing levels of adult stress are associated with a moderate increase in positive marital experiences over time.

These findings fit with research and theory on cumulative disadvantage (Dannefer, 2003) in that the relationships of those who report high childhood stress appear to be more vulnerable to stress in adulthood, that is, adversity over the life course has a cumulative effect on adult outcomes. But our findings also suggest that reductions in adult stress burden may lead to improvement in the marital relationships of those who recall high childhood stress. This might be read as a benefit to those who experienced high levels of stress in childhood. This seemingly positive effect, however, may reflect the exaggerated importance of the social environment to the well-being of such adults. Attachment theory suggests that the threat of relationship loss creates anxiety (Bowlby, 1973), and continuing threat and disruption in childhood may produce anxiety in unpredictable situations (Block, Block, & Gjerde, 1986). Children who experience high levels of family stress may be very sensitive to nuances of change in the family, becoming exceptionally hopeful in the face of improved family circumstances and poignantly disappointed in the face of increasingly stressful family circumstances, perhaps especially when such stress is recurring (Wallace, 1996). When such children reach adulthood, they may experience echoes of these hopes and fears in the face of adult stressors. If this occurs, they may feel especially concerned and strained in their marital relationships during periods of elevated stress and especially hopeful and positive (and perhaps relieved) during periods of declining stress. This may help explain why the marital relationships of those who experienced high levels of childhood family stress are more affected by fluctuations in adult stress burden—for better and for worse. One benefit of growing up with low levels of family stress may be greater stability in marital quality in adulthood—even in the face of rising levels of stress. We are currently evaluating qualitative data to further explore this possibility.

In sum, we find that early life course experiences with stress dovetail with recent stress experiences in adulthood to influence both overall levels of positive marital experiences and change in those experiences over time. These findings build on recent work emphasizing the importance of taking a long view of life course experiences not only in a cumulative sense but in an interactive sense as well (Wheaton & Clarke, 2003). Early life course experiences set the stage for future life course experiences. Here, we see that childhood stress burden may shape the influence of adult stress burden on marital trajectories.

Policy Implications

It is not new that childhood family experiences shape marital relationships in adulthood. The current findings, however, suggest two new insights into the processes underlying this linkage. First, our findings suggest that low childhood stress provides a foundation that may facilitate stability in later marital experiences. Interventions that help children to cope with family stress should have positive consequences not only in childhood but throughout the life course—by enhancing stability in marital experiences even in the face of stress. Second, the finding that high levels of childhood family stress may set the stage for greater marital volatility in response to stress in adulthood points to several issues for policymakers. A great deal of contemporary political and policy attention is directed toward insuring marital success. Policymakers might note several factors that could contribute to such success: (a) policies and programs that reduce family stress for children (e.g., reducing economic strain and providing clinical resources for families under stress) and (b) policies and programs that target the reduction of stress or, at least, educate individuals about the effects of stress on marriage and teach individuals more effective ways of coping with stress when it occurs.

Methodological Considerations for Future Research

Stress measures

The goal of the present study was to examine developmental trajectories of marital experiences following stress exposure. This issue is best addressed with growth curve analysis, which requires at least three data points. The Americans’ Changing Lives data are well suited to this analysis in the sense that we have three waves of data, measures of our key constructs, and a reasonable sample size. Because our analytic approach required that we measure stress burden at three time points, however, we had to measure Time 1 stress based on stress that occurred immediately prior to the study period (and assessed retrospectively at Time 1). Ideally, we would like to examine marital relationships both pre- and poststress exposure and over a longer period of time. Better specified models will require additional data points in order to capture discontinuities and possible nonlinearities in the growth trajectories in response to changing levels of stress. Although these limitations should be addressed in future work, information provided by the present growth curve analysis can advance our understanding of the potential impact of stress on marital quality by promoting a view of marital relationships as having their own developmental trajectories, trajectories that may be shaped by exposure to stress. We hope that this perspective will lead to additional studies of stress and marital quality that follow individuals and couples over longer periods of time.

Reciprocal effects

Although stress may be both a cause and an effect of marital experiences, our models treat adult stress as a time-varying exogenous variable that affects marital experiences. Initial stress level is allowed to affect level and change in marital quality, and change in stress is allowed to influence change in marital experiences. This analytic approach is driven by previous research and our theoretical framework, both of which point to the impact of stress on marital quality. We cannot, however, rule out marital effects on adult stress levels. This limitation points to the need for future research to conduct a rigorous examination of the potential endogeneity of stress using alternative models positing that marital experiences and stress are jointly determined. This type of analysis will require multiple data points over time.

Couple-level data

We analyze a sample of individuals to examine within- and between-individual variation in the influence of stress burden on personal evaluations of marital quality. Couple-level data would allow for a more nuanced analysis of the complex ways in which stress experienced by each spouse might differentially influence perceptions of marital quality. First, one’s own adulthood and childhood stressful experiences and those of one’s spouse may have different consequences for the way that each spouse evaluates marriage. Second, the stressful experiences of each spouse may interact to influence marital experiences in unexpected ways. For example, given that homogamy is generally associated with better marital quality (Lehrer & Chiswick, 1993), past and present stressful experiences may be less likely to undermine marital quality when both spouses report similar levels of stressful experiences. In contrast, high levels of stress between spouses may be especially likely to undermine marital quality because of the excessive strain experienced by both partners. Evaluation of these hypotheses in the future will depend on data collection efforts that obtain comprehensive assessments of stress and marital quality from both spouses.

Selectivity

A potential problem with marital quality research is that marriages of higher stress and poorer quality may be removed from the population as divorces occur, leaving only marriages of higher quality among individuals of older ages. We adopt a procedure to estimate the propensity for divorce/separation and include this term in our final models predicting marital quality. Although we cannot rule out the possibility of selection bias in our results, this statistical strategy gives us confidence in the soundness of our findings. In fact, if selection is operative, this is likely to result in an underestimation of the effects of stress on marital quality (Webster, Orbuch, & House, 1995). Of course, sample attrition may affect our findings in ways that are difficult to estimate, and we cannot resolve this issue with the present data. Because we base our inference on a selected sample (remaining intact over an 8-year period), we must be cautious about extending the results to the wider population of marriages. Perhaps some of the longitudinal newlywed studies that are now being followed over time will allow a better examination of the selection issue and will illuminate how selection and causation work together to influence marital experiences.

Conclusion

Several studies document that marital quality tends to decline over time (VanLaningham et al., 2001), and most of us think of stress as taking a toll on marriage. Our findings support this view but also indicate that some couples may be better able than others to weather the effects of stress. In particular, we find that those individuals who recall little family stress in childhood are fairly stable in their marital experiences over time, even as adult stress levels fluctuate up and down. The marital experiences of those individuals who recall high levels of family stress in childhood, however, are more reactive to fluctuating levels of stress in adulthood. We draw on attachment theory to suggest that these individuals were sensitive to changing levels of stress in childhood, experiencing relief when family stress declined and anxiety when family stress increased. Past research shows that childhood family troubles may lead to more tenuous adult attachments (Sabatelli & Bartle- Haring, 2003), and the present findings suggest a possible way in which childhood family stress interacts with stress in adulthood—often a largely uncontrollable factor in life—to undermine adults’ marital relationships. They also suggest that low levels of family stress in childhood may be a stabilizing resource for marriages throughout adulthood. Our results add to a new and exciting body of research (e.g., Wheaton & Clarke, 2003) showing how early and late life course experiences work together to influence individuals over the life course.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (RO1 AG17455).

Contributor Information

Debra Umberson, Email: umberson@mail.la.utexas.edu, Department of Sociology, The University of Texas, 1 University Station A1700, Austin, TX 78712-1088.

Kristi Williams, Department of Sociology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43219.

Daniel A. Powers, Department of Sociology, The University of Texas, 1 University Station A1700, Austin, TX 78712-1088

Hui Liu, Department of Sociology, The University of Texas, 1 University Station A1700, Austin, TX 78712-1088.

Belinda Needham, Department of Sociology, The University of Texas, 1 University Station A1700, Austin, TX 78712-1088.

References

- Amato PR, DeBoer DD. The transmission of marital instability across generations: Relationship skills or commitment to marriage? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:1038–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Lang ME, Rovine M. Stability and change in marriage across the transition to parenthood: A second study. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1985;47:855–865. [Google Scholar]

- Block JH, Block J, Gjerde P. The personality of children prior to divorce: A prospective study. Child Development. 1986;57:827–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1986.tb00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss, Vol. 2: Separation. New York: Basic; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, Fincham FD, Beach SRH. Research on the nature and determinants of marital satisfaction: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:964–980. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, Karney BR. Understanding and altering the longitudinal course of marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:862–879. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Application of hierarchical linear models to assessing change. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Levenson RW, Gottman JM. Emotional behavior in long-term marriage. Psychology and Aging. 1995;10:140–149. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Nicolas P, Gray-Little B. Effect of economic resources on marital quality in Black married couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:645–655. [Google Scholar]

- Cohan CL, Bradbury TN. Negative life events, marital interaction, and the longitudinal course of newlywed marriage. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:114–128. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer D. Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: Cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. Journals of Gerontology. 2003;58B:327–337. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.s327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, George LK, Shanahan MJ. Psychosocial stress over the life course. In: Kaplan H, editor. Perspectives on psychosocial stress. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 245–290. [Google Scholar]

- Ensel WM, Peek KM, Lin N, Lai G. Stress in the life course: A life history approach. Journal of Aging and Health. 1996;8:389–416. doi: 10.1177/089826439600800305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Bradbury TN. The assessment of marital quality: A reevaluation. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1987;49:797–809. [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Lynch SM. Race differences in depressive symptoms: A dynamic perspective on stress exposure and vulnerability. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2003;44:353–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn ND. Quantitative research on marital quality in the 1980s: A critical review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:818–831. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica. 1979;47:153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Helms-Erickson H. Marital quality ten years after the transition to parenthood: Implications of the timing of parenting and the division of housework. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;53:285–295. [Google Scholar]

- House JS. Americans’ Changing Lives: Wave 1. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center; 1986. [computer file] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DC, Blazer DG, George LK. Age differences in life events: A multivariate controlled analysis. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1988;27:207–220. doi: 10.2190/F9RP-8V9D-CGH7-2F0N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Assessing longitudinal change in marriage: An introduction to the analysis of growth curves. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:1091–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer EL, Chiswick CU. Religion as a determinant of marital stability. Demography. 1993;30:385–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz FO, Conger RD, Simon RL, Whitbeck LB, Elder GH. Economic pressure and marital quality: An illustration of the method variance problem in the causal modeling of family processes. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:375–388. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD. Childhood parental loss and adult depression. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 1991;32:205–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD, Kaiser K. Childhood emotional and behavioral problems and educational attainment. American Sociological Review. 2004;69:636–658. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Authors; (1998–2004). [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L, Aneshensel CS, LeBlanc AJ. The forms and mechanisms of stress proliferation: The case of AIDS caregivers. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 1997;38:223–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L, Skaff MM. Stress and the life course: A paradigmatic alliance. Gerontologist. 1996;36:239–247. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Schoenberg SP, Holmes SJ, Ratcliff KS, Benham A, Works J. Early home environment and retrospective recall: A test for concordance between siblings with and without psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1985;55:27–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb03419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatelli RM, Bartle-Haring S. Family-of-origin experiences and adjustment in married couples. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Schraedley PK, Turner RJ, Gotlib IH. Stability of retrospective reports in depression: Traumatic events, past depressive episodes, and parental psychopathology. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2002;43:307–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolewski JM, Amato PR. Economic hardship in the family of origin and children’s psychological well-being in adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Avison WR. Status variations in stress exposure: Implications for the interpretation of research on race, socioeconomic status, and gender. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2003;44:488–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Wheaton B, Lloyd DA. The epidemiology of social stress. American Sociological Review. 1995;60:104–125. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. Marriage as support or strain? Marital quality following the death of a parent. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:709–723. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Williams K, Powers DP, Chen MD, Campbell AM. As good as it gets? A life course perspective on marital quality. Social Forces. 2005;84:493–511. doi: 10.1353/sof.2005.0131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanLaningham J, Johnson DR, Amato P. Marital happiness, marital duration, and the U-shaped curve: Evidence from a five-wave panel study. Social Forces. 2001;79:1313–1341. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace BC. Adult children of dysfunctional families: Prevention, intervention, and treatment for community mental health promotion. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Webster PS, Orbuch TL, House JS. Effects of childhood family background on adult marital quality and perceived stability. American Journal of Sociology. 1995;101:404–432. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B. Sampling the stress universe. In: Avison W, Gotlib I, editors. Stress and mental health: Contemporary issues and prospects for the future. New York: Plenum; 1994. pp. 77–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B, Clarke PA. Space meets time: Integrating temporal and contextual influences on mental health in early adulthood. American Sociological Review. 2003;68:680–706. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B, Gotlib IH. Trajectories and turning points over the life course: Concepts and themes. In: Gotlib IH, Wheaton B, editors. Stress and adversity over the life course: Trajectories and turning points. Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- White LK. Determinants of divorce: A review of research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:904–912. [Google Scholar]