Abstract

Background:

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics may improve medication adherence, thereby improving overall treatment effectiveness. This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of risperidone long-acting injection in schizophrenic patients switched from oral antipsychotic medication.

Methods:

In a 12-month, multicenter, open-label, noncomparative study, symptomatically stable patients on oral antipsychotic medication with poor treatment adherence during the previous 12 months received intramuscular injections of risperidone long-acting injection (25 mg starting dose) every 2 weeks. The primary endpoint was the change in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score.

Results:

Of the 60 patients who were screened, 53 received at least one injection (safety population), and 51 provided at least one postbaseline assessment. Mean PANSS total scores improved significantly throughout the study and at endpoint. Significant improvements were also observed in Clinical Global Impression of Severity, Personal and Social Performance, and Drug Attitude Inventory scales. Risperidone long-acting injection was safe and well-tolerated. Severity of movement disorders on the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale was reduced significantly. The most frequently reported adverse events were insomnia (22.6%), increased prolactin (17.0%), and weight gain (13.2%).

Conclusion:

Risperidone long-acting injection was associated with significant symptomatic improvements in stable patients with schizophrenia following a switch from previous antipsychotic medications.

Keywords: patient compliance, adherence, risperidone, delayed-action preparations, schizophrenia

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic mental disorder that affects approximately 1% of the world population and is characterized by a relapsing course with significant burden for patients, families, and society.1–3 Although many patients receiving chronic antipsychotic therapy can be considered clinically stable, a subgroup of patients will eventually have poor outcomes, not achieving optimal symptom relief.4 Premature discontinuation and poor prescription compliance are well established reasons for suboptimal effectiveness in clinical practice,5–12 and 40%–50% of schizophrenic patients are believed to be only partially compliant.8,12 Nonadherence to oral antipsychotic therapy is associated with potential symptom re-emergence and a higher risk of relapse.13–18

Relapses are responsible for frequent inpatient admissions, and account for 80% of overall schizophrenia treatment costs.19,20 Their consequences include social and overall productivity impairment, increased risk of a poor prognosis, and prolonged recovery in subsequent episodes.21,22 In this setting, alongside symptom remission, relapse prevention is a major therapeutic goal for schizophrenic patients. Atypical antipsychotics are currently a critical part of schizophrenia management worldwide, and several studies have demonstrated their efficacy and a better tolerability profile relative to conventional agents, with reduced risk of extrapyramidal side effects.23–25

Risperidone long-acting injection was the first injectable, long-acting, second-generation agent to become available, providing continuous medication delivery and reducing plasma level fluctuations.26,27 A robust set of evidence has shown that risperidone long-acting injection administered intramuscularly every 2 weeks improves symptom control, prevents relapses, positively impacts patients’ health-related quality of life, and reduces hospitalizations.13,21,28–32 Because compliance monitoring is a critical issue for patients with schizophrenia, risperidone long-acting injection can potentially minimize the risk of intermittent or interrupted treatment, by ensuring more stable drug levels through slow and steady release of risperidone over several weeks.13,29,30 Individuals with a previous history of nonadherence or partial adherence are a subset of patients of special concern for clinicians regarding future compliance behavior. The purpose of the present study was to assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of switching clinically stable patients with schizophrenia and a history of nonadherence on oral antipsychotic therapy to long-acting risperidone.

Methods

This was a 50-week, multicenter, open-label, noncomparative trial of risperidone long-acting injection (Risperdal Consta®; Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies, Johnson and Johnson, Sao Paolo, Brazil) in stable patients with schizophrenia attending seven Brazilian centers who were switched from oral treatment. A 50-week study duration was chosen to provide information relevant to clinical decision-making in the real-world setting, given that long-term follow-up is essential for schizophrenia patients. As required in multicenter studies, raters from each of the seven sites went through a training process on all clinical assessment scales to be used before initiating the trial. All raters were required to have prior clinical experience with schizophrenic patients and documented experience administering at least the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), which was the primary outcome measure in the trial. The study was approved by the ethics committee at each participating site and written consent was obtained from each patient or their legal representative before enrollment.

Patients

Patients were recruited for the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition Text Revision (DSM-IV) criteria for schizophrenia; age 18–50 years; current treatment with oral antipsychotics (both first- and second-generation); history of nonadherence to antipsychotic treatment within the previous 12 months; and PANSS ≤ 90 and a PANSS ≤ 4 for conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, suspiciousness, and unusual thought content. Nonadherent patients were those fulfilling at least one of the following criteria: hospitalization due to interruption or irregular use of medication within the previous 12 months; clinical worsening due to irregular use of medication; patient refusal to take medication, as reported by family members; difficulty convincing patient to accept medication, as reported by family members; and at least one treatment interruption with worsening of symptoms. Exclusion criteria included a history of refractoriness to antipsychotic treatment, previous use of clozapine, use of another depot antipsychotic within the previous 12 months, another major axis disorder, and risk of suicide. Women of childbearing age not using an approved method of birth control were also excluded.

Study medication

Patients continued their outgoing antipsychotic for the first 3 weeks to ensure adequate drug coverage, and the previous medication was interrupted thereafter. At the first study visit, all eligible patients were prescribed oral risperidone1 mg for 3 days as a sensitivity and tolerability test. Patients received intramuscular injections of risperidone long-acting injection at an initial dose of 25 mg every 2 weeks. The dose could be increased to up to 50 mg at the investigator’s discretion. Biperidene for extrapyramidal symptoms and clonazepam for anxiety and insomnia were allowed as concomitant medications.

Safety and efficacy measures

The primary efficacy measure was the change from baseline to endpoint for the total score on PANSS.33 Secondary efficacy measures included the change from baseline in PANSS subscales (negative symptoms, positive symptoms, general psychopathology), Clinical Global Impression (CGI),34 and Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP).35 The Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI-10) was employed to assess patients’ attitudes towards psychiatric medication.36

PSP is a 100-point classification scale that measures personal and social activity in four behavioral domains (socially useful activities, personal and social relationships, self-care, and disturbing and aggressive behaviors). The final scale score is obtained summing the scores of all four domains, and ranges from 1 to 100. The higher the observed score, the better the performance. DAI-10 is a 10-item dichotomous (true or false) answer scale that enables classification of patients based upon their attitudes towards medication. A positive final total score means a positive subjective response (compliant) and a negative total score means a negative subjective response (noncompliant). Answers are coded as positive (+1 point) or negative (−1 point), and the final score is the sum of all points.

Spontaneously reported adverse events were recorded by the investigator at all visits (weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 38, and 50), and severity of movement disorders was evaluated using the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS).37 Electrocardiograms and blood samples for laboratory analysis were obtained at screening, week 24, and endpoint.

Statistical analysis

The sample size required to provide the desired 80% power at a two-sided alpha of 0.05 was 60 patients, considering the mean reduction in PANSS scores reported in two previously published clinical studies of Risperdal Consta.30,38 All patients who received at least one injection of risperidone long-acting injection and had at least one postbaseline efficacy assessment (intention-to-treat population) were included in the efficacy analysis. The safety population comprised patients who received at least one injection, regardless of efficacy measurement status. Changes in efficacy measures from baseline to endpoint (week 50) were analyzed by the paired t-test and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for normal and asymmetric continuous variables as appropriate. Scores measured over time (PANSS, CGI, PSP, DAI, and ESRS) were compared by repeated-measures analysis of variance using a mixed linear model for time effect (within-group factors). Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS® (v 9.1.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC)

Results

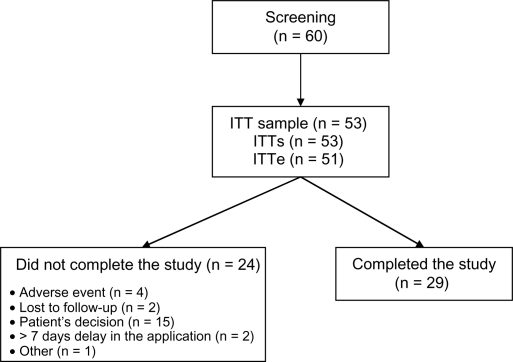

Of the 60 patients who were screened, seven patients could not be enrolled in the study for the following reasons: injectable depot antipsychotic use within the previous 12 months (n = 1); a clinically significant abnormality in the screening tests (n = 2, one electrocardiographic abnormality and one anemia); self-withdrawal (n = 2); and loss to follow-up (n = 2, both before receiving the study medication. Fifty-three patients received at least one dose of risperidone long-acting injection (safety population, n = 53); of these, two were excluded from the efficacy analysis for not undergoing any postbaseline assessment (intention-to-treat efficacy population, n = 51). The 50-week trial was completed by 29 patients (54.7%). Reasons for discontinuation are presented in Figure 1. Most dropouts were due to patient’s request for withdrawal (62.5%); 16.7% were adverse event-related, and none were due to lack of efficacy.

Figure 1.

Study participants.

Notes: All patients who received at least one injection of risperidone long-acting injection and had at least one postbaseline efficacy assessment (intention-to-treat population) were included in the efficacy analysis (ITTe). The safety population comprised all patients who received at least one injection, regardless of efficacy measurement status (ITTs).

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the total sample and the subsample of study completers are summarized in Table 1. The study group was predominantly male (73.6%) with a mean age of 33.6 years. The median disease duration was 5.5 years (mean ± standard deviation 9.2 ± 9.9 years). Most patients were switched from oral risperidone (41.5%), followed by haloperidol (22.6%) and chlorpromazine (11.3%). Final doses (week 48) of risperidone long-acting injection were 25 mg in 38.1%, 37.5 mg in 38.1%, and 50 mg in 23.8% of patients. Regarding concomitant medication, 15 (28.3%) patients received clonazepam, 10 (18.9%) received biperidene, 17 (32.1%) received risperidone, and 14 (26.4%) received haloperidol. Haloperidol and risperidone were used as adjuvant antipsychotics. It was not possible to identify clinically relevant differences between study completers and the initial sample.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

| Age (years) | Total sample (n = 59) | Study completers (n = 29) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | 33.6 (9.1) | 33.2 (10.3) |

| Median (range) | 34 (21–57) | 30 (21–57) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 39 (73.6) | 19 (65.5) |

| Female | 14 (26.4) | 10 (34.5) |

| Disease duration (years) | n = 36 | n = 29 |

| Mean (SD) | 9.2 (9.9) | 9.9 (11.0) |

| Median (range) | 5.5 (0–41) | 5.5 (0–39) |

| Inpatient admissions in the last year, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 11 (20.8) | NA |

| Previous antipsychotic treatment, n (%) | n = 53 | |

| Chlorpromazine | 6(11.3) | NA |

| Haloperidol | 12(22.6) | NA |

| Risperidone | 22(41.5) | NA |

| Assessments | Mean (SD) | |

| PANSS (n = 53) | ||

| Positive scale | 14.1 (4.8) | 13.2 (5.1) |

| Negative scale | 18.3 (5.6) | 18.5 (6.6) |

| Total | 63.5 (14.1) | 61.1 (15.7) |

| CGI-S (n = 53) | 3.6 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.8) |

| DAI-10 (n = 51) | 2.8 (4.7) | 2.2 (5.0) |

Abbreviations: PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndromes Scale; DAI, Drug Attitude Inventory; CGI-S, Clinician’s Global Impression of Disease Severity; SD, standard deviation; NA, not available.

Over a 50-week period, there were significant reductions in total PANSS score and also in the PANSS positive, negative, and general psychopathology subscales (Table 2). The mean PANSS total score was significantly reduced from baseline to endpoint (58.8 ± 1.82 vs 49.72 ± 2.32; P = 0.0002). A significant improvement was seen at week 4, and this effect was maintained throughout the study. In addition, significant improvements were observed from baseline to endpoint and during the study in all PANSS subscales.

Table 2.

Positive and Negative Syndromes Scale measures (n = 51)

| Week | Positive scale mean (SE) | Negative scale mean (SE) | General psychopathology scale mean (SE) | Total scale mean (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 12.61 (0.60) | 16.69 (0.68)* | 29.51 (0.97) | 58.80 (1.82) |

| 2 | 12.41 (0.60) | 15.49 (0.68)** | 27.63 (0.97)* | 55.53 (1.82)* |

| 4 | 12.06 (0.60)* | 15.25 (0.69)** | 26.51 (0.98)** | 53.82 (1.83)** |

| 8 | 11.00 (0.61)* | 14.13 (0.69)** | 26.14 (1.00)** | 51.28 (1.86)** |

| 16 | 10.90 (0.65)* | 13.87 (0.72)** | 25.77 (1.07)** | 50.55 (1.98)** |

| 24 | 10.01 (0.69)** | 13.56 (0.75)** | 25.33 (1.16)** | 48.95 (2.13)** |

| 38 | 10.37 (0.73)** | 13.22 (0.78)** | 23.82 (1.24)** | 47.40 (2.26)** |

| 50 | 10.87 (0.75)* | 13.40 (0.79)** | 25.47 (1.28)** | 49.72 (2.32)** |

| Fixed effects test (week) | P = 0.0009 | P < 0.0001 | P = 0.0017 | P < 0.0001 |

Notes:

P < 0.05 vs week 0;

P < 0.01 vs week 0.

Abbreviation: SE, standard error of the mean.

Mean CGI also significantly improved from baseline to endpoint (mean ± standard error of the mean = 3.55 ± 0.13 vs 3.19 ± 0.16; P = 0.0131). The factor “week of treatment” had a statistically significant effect from week 4 (P < 0.01) and these clinical benefits remained stable until the final visit (Table 3). For the PSP scale, the time factor also had a positive impact on mean performance scores, which improved from 60.0 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 54.2–65.7) at baseline to 69.1 (95% CI: 64.8–73.4) at week 50 (P = 0.0002, Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinician’s Global Impression of Disease Severity (n = 51), Personal and Social Performance (n = 34), and Drug Attitude Inventory-10 (n = 51) measures

| Week |

CGI –S |

|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | |

| 0 | 3.55 (0.13) |

| 2 | 3.37 (0.13)* |

| 4 | 3.30 (0.13)** |

| 8 | 3.21 (0.13)** |

| 16 | 3.10 (0.14)** |

| 24 | 2.92 (0.15)** |

| 38 | 2.94 (0.15)** |

| 50 | 3.19 (0.16)* |

| Test of fixed effects (week) of the adjusted model: P < 0.0001. | |

| Week | PSP scale |

| Mean (SE) | |

| Baseline (n = 10) | 60.0 (2.9) |

| 8 (n = 17) | 66.4 (2.4)* |

| 16 (n = 19) | 72.6 (2.3)** |

| 24 (n = 29) | 71.7 (2.1)** |

| 38 (n = 29) | 71.8 (2.1)** |

| 50 (n = 26) | 69.1 (2.2)** |

| Test of fixed effects (week) of the adjusted model: P = 0.0002. | |

| Week | DAI-10 |

| Mean (SE) | |

| Baseline | 2.78 (0.62) |

| 8 | 4.45 (0.64)* |

| 24 | 4.59 (0.69)* |

| 50 | 5.07 (0.77)** |

Notes: Test of fixed effects (week) of the adjusted model: P < 0.0001;

P < 0.05 vs baseline;

P < 0.01 vs baseline.

Abbreviations: DAI-10, Drug Attitude Inventory; CGI-S, Clinician’s Global Impression of Disease Severity; PSP, Personal and Social Performance Scale; SE, standard error of the mean.

DAI-10 scores were measured at four different visits from baseline to endpoint. At all visits, significant improvements were observed and the mean (± standard error of the mean) scores rose from 2.78 ± 0.68 to 5.07 ± 0.77 (P = 0.0062). There was a progressive and sustained increase in DAI-10 scores, showing positive attitudes towards risperidone long-acting injection throughout the study, as shown in Table 3.

Adverse events were reported by 40 (75.5%) patients. Adverse events reported in more than 10% of patients were insomnia (22.6%), increased prolactin levels (17.0%), and weight gain (13.2%). Investigators categorized 22 (41.5%) adverse events as likely or very likely related to the study drug (Table 4). Three serious adverse events were reported by the investigators, ie, psychomotor agitation, worsening of symptoms, and worsening of psychotic symptoms. There were three (5.7%) early discontinuations due to adverse events (sexual dysfunction, decreased libido, psychomotor agitation, and worsening of pre-existing symptoms).

Table 4.

Frequency of adverse events during the study period (efficacy population)

| Adverse events reported by ≥5% of patients, n (%) | n = 53 |

| Insomnia | 12 (22.6) |

| Increased prolactin | 9 (17.0) |

| Weight gain | 7 (13.2) |

| Anxiety | 3 (5.7) |

| Epigastralgia | 3 (5.7) |

| Reduced appetite | 3 (5.7) |

| Adverse events related to the study drug, n (%) | n = 53 |

| Increased prolactin | 9 (17.0) |

| Weight gain | 5 (9.4) |

Severity of movement disorders was significantly reduced during treatment with risperidone long-acting injection (Table 5). Significant improvements were noted on the ESRS overall scale, subjective evaluation, and extrapyramidal symptoms item from week 4 (P < 0.0001). Changes in laboratory findings other than serum prolactin were not clinically significant, although high-density lipoprotein and creatinine changes reached statistical significance (Table 6). The 29 patients for whom weight data at baseline and endpoint were available showed a mean weight gain of 2.8 ± 4.6 kg (P < 0.001).

Table 5.

Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (n = 50)

| Week |

ESRS (total score) |

|---|---|

| Mean | |

| 0 | 0.46 (0.07) |

| 2 | 0.416 (0.07)* |

| 4 | 0.272 (0.07)* |

| 8 | 0.289 (0.07)** |

| 16 | 0.271 (0.08)** |

| 24 | 0.221 (0.08)** |

| 50 | 0.089 (0.08)** |

Notes: Test of fixed effects (week) of the adjusted model: P < 0.0001;

P < 0.01 vs baseline.

Abbreviation: ESRS, Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale.

Table 6.

Laboratory parameters at baseline and at final evaluation (on week 50 or at the patient’s last evaluation in case of early withdrawal from the study)

| Laboratory parameters | Evaluation | Mean (SD) | Minimum | Maximum | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | Baseline | 172.9 (34.5) | 112 | 279 | 0.758 |

| Final | 171.7 (33.2) | 106 | 233 | ||

| HDL (mg/dL) | Baseline | 45.6 (13.1) | 27 | 78 | 0.044 |

| Final | 43.5 (13.5) | 24 | 76 | ||

| LDL (mg/dL) | Baseline | 99.6 (28.8) | 32 | 184 | |

| Final | 97.0 (29.3) | 24 | 163 | 0.384 | |

| VLDL (mg/dL) | Baseline | 23.1 (11.6) | 9 | 62 | |

| Final | 27.1 (14.4) | 7 | 73 | 0.074 | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | Baseline | 0.86 (0.17) | 0.40 | 1.10 | |

| Final | 0.96 (0.18) | 0.56 | 1.28 | 0.005 | |

| Fasting glycemia (mg/dL) | Baseline | 92.1 (25.6) | 75 | 249 | |

| Final | 92.0 (10.9) | 57 | 114 | 0.153 | |

| Prolactin (ng/mL) | Baseline | 36.2 (40.1) | 2.1 | 181.0 | |

| Final | 49.9 (43.6) | 4.1 | 232.4 | 0.006 | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | Baseline | 112.5 (62.0) | 42.0 | 313.0 | |

| Final | 123.8 (71.7) | 36.0 | 367.0 | 0.201 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; HDL, high-density lipoprotein LDL, low-density lipoprotein; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein.

Discussion

The findings of this open-label study demonstrate that risperidone long-acting injection was an effective treatment in a real-world setting for clinically stable Brazilian patients with schizophrenia who were switched from other antipsychotic agents due to poor compliance, as assessed by change in scores on PANSS measures and CGI-S. Patients achieved significant clinical improvements in terms of symptom control when switched directly to risperidone long-acting injection from their current antipsychotic therapy. Most patients maintained the lower doses of risperidone long-acting injection, ie, 25 mg and 37.5 mg, during the trial. The mean PANSS total score was significantly reduced from baseline to endpoint, and patients remained stable, not showing any worsening of symptoms. Most clinical improvement was apparent in the first month after switching. Results from a number of other clinical studies have also reported significant and sustained clinical improvement in patients directly switched to risperidone long-acting injection from their previous antipsychotic agents.29,38,39

In a 12-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial by Kane et al, risperidone long-acting injection was associated with significantly greater improvements in PANSS and CGI-S scores at endpoint compared with placebo.30 Significant improvements in total PANSS scores (P < 0.01), positive symptoms (P < 0.01), and negative symptoms (P < 0.001) were also observed during an international, open-label, 12-month study conducted by Fleischhacker et al in patients with schizophrenia who were switched to risperidone long-acting injection from oral or long-acting conventional or oral atypical antipsychotics.29

Risperidone long-acting injection was well-tolerated, with minimal weight change and an overall favorable safety profile. ESRS score showed minimum change between baseline and endpoint. Although of minimum magnitude in clinical terms, the statistically significant change in high-density lipoprotein could potentially raise concern about metabolic side effects. However, the observed decrease was not accompanied by consistent changes in total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, very low-density lipoprotein, triglycerides, and fasting glycemia, reinforcing the absence of clinically sound metabolic effects of risperidone long-acting injection in this sample. The creatinine increase, although statistically significant, was considered clinically irrelevant.

The incidence of adverse events was comparable with those reported in previous studies. According to the report by Kane et al, risperidone long-acting injection was generally well-tolerated, with an overall incidence of adverse events similar to that with placebo in comparative trials.30 In that study, similar proportions of patients reported adverse events in the active and control group, while serious adverse events were more frequent in the placebo group (23.5%) than in the 25, 50, and 75 mg risperidone long-acting injection groups (13%, 14%, and 15%, respectively).30 Results from other studies have also reported that patients can be safely switched from oral conventional or atypical therapy and conventional long-acting agents to risperidone long-acting injection.38,40–42

These findings confirm the effectiveness of switching stable patients with schizophrenia from other antipsychotics to risperidone long-acting injection in a Brazilian real-world setting. Following a switch to risperidone long-acting injection, stable patients showed further significant improvements in symptom control over the treatment period, reducing their PANSS total score and subscales and CGI-S scores.

Some of the limitations of the study were its small sample size, a relatively high dropout rate (42.5%), and the open-label design. In absolute terms, the observed dropout rate was not significantly greater in magnitude than that observed in previous atypical antipsychotic trials (33.5% in fixed-dose studies and 45.0% in flexible-dose studies).43 This study enrolled only patients with a previous history of compliance issues, which could also be a factor explaining the higher dropout rates, especially those due to patient request. Subgroup analysis according to study completion status was not performed.

Another limitation is the lack of inter-rater reliability assessments as part of the trial. Rater training was performed to improve raters’ clinical skills and to ensure standardized clinical assessments before the study initiation, but statistical evaluation of inter-rater reliability was not conducted. Nevertheless, this study yielded useful knowledge on the effectiveness and safety of risperidone long-acting injection in a Brazilian population over a 12-month study period, and observed significant clinical improvements after switching from oral antipsychotics to risperidone long-acting injection. These findings justify further comparative studies addressing differences in terms of relapse prevention.

Conclusion

Long-acting injectable risperidone is an effective and safe treatment alternative for patients with schizophrenia and a history of poor adherence to oral treatment. The study indicates a favorable tolerability profile, a positive effect on personal and social functioning, and adequate patient treatment acceptance. These findings reinforce long-acting injectable risperidone as a reasonable alternative for long-term care of stable schizophrenia patients in whom compliance issues are anticipated.

Footnotes

Disclosure

This study was sponsored by Janssen-Cilag Farmaceutica Ltda, Brazil.

References

- 1.Mari JJ, Leitão RJ. The epidemiology of schizophrenia. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2000;22(Suppl I):15–17. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD, et al. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(11):977–986. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800350011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States and sociodemographic characteristics: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;88(1):35–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kane JM. Pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(10):1396–1408. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Faries D, Lacro JP, Dolder CR. A prospective study of risk factors for nonadherence with antipsychotic medication in the treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(7):1114–1123. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byerly MJ, Nakonezny PA, Lescouflair E. Antipsychotic medication adherence in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(3):437–452. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane JM. Treatment adherence and long-term outcomes. CNS Spectrums. 2007;12(10 Suppl 17):21–26. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900026304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, Leckband SG, Jeste DV. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(10):892–909. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):1209–1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perkins DO, Gu H, Weiden PJ, et al. Predictors of treatment discontinuation and medication nonadherence in patients recovering from a first episode of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or schizoaffective disorder: a randomized, double-blind, flexible-dose, multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(1):106–113. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosa MA, Marcolin MA, Elkis H. Evaluation of the factors interfering with drug treatment compliance among Brazilian patients with schizophrenia. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2005;27(5511):178–184. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462005000300005. Portuguese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, Locklear J. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(8):886–891. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.8.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knox ED, Stimmel GL. Clinical review of a long-acting, injectable formulation of risperidone. Clin Ther. 2004;26(12):1994–2002. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Law MR, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Adams AS. A longitudinal study of medication nonadherence and hospitalization risk in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(1):47–53. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masand PS, Narasimhan M. Improving adherence to antipsychotic pharmacotherapy. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2006;1(1):47–56. doi: 10.2174/157488406775268255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241–247. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Svarstad BL, Shireman TI, Sweeney JK. Using drug claims data to assess the relationship of medication adherence with hospitalization and costs. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(6):805–811. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiden PJ, Olfson M. Cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1995;21(3):419–429. doi: 10.1093/schbul/21.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daltio CS, Mari JDJ, Ferraz MB. Direct medical costs associated with schizophrenia relapses in health care services in the city of São Paulo. Rev Saúde Pública. 2011;45(1):14–23. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102010005000049. Portuguese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leitão RJ, Ferraz MB, Chaves AC, Mari JJ. Cost of schizophrenia: direct costs and use of resources in the State of São Paulo. Schizophrenia. 2006;40(2):304–309. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102006000200017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Csernansky JG, Mahmoud R, Brenner R. A comparison of risperidone and haloperidol for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(1):16–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa002028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wyatt RJ. Neuroleptics and the natural course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17(2):325–351. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis JM, Chen N, Glick ID. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of second-generation antipsychotics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(6):553–564. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leucht S, Pitschel-Walz G, Abraham D, Kissling W. Efficacy and extrapyramidal side-effects of the new antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and sertindole compared to conventional antipsychotics and placebo. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Res. 1999;35(1):51–68. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, et al. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):31–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61764-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eerdekens M, Van Hove I, Remmerie B, Mannaert E. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of long-acting risperidone in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;70(1):91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ereshefsky L, Mascarenas CA. Comparison of the effects of different routes of antipsychotic administration on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(Suppl 16):18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chue P, Eerdekens M, Augustyns I, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of long-acting risperidone and risperidone oral tablets. Eur Neuro Psychopharmacol. 2005;15(1):111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleischhacker WW, Eerdekens M, Karcher K, et al. Treatment of schizophrenia with long-acting injectable risperidone: a 12-month open-label trial of the first long-acting second-generation antipsychotic. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(10):1250–1257. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kane JM, Eerdekens M, Lindenmayer J-P, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone: efficacy and safety of the first long-acting atypical antipsychotic. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1125–1132. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Möller H-J. Long-acting injectable risperidone for the treatment of schizophrenia: clinical perspectives. Drugs. 2007;67(11):1541–1566. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767110-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nasrallah H, Duchesne I, Mehnert A, Janagap C, Eerdekens M. Health-related quality of life in patients with schizophrenia during treatment with long-acting, injectable risperidone. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(4):531–536. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101(4):323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Awad AG. Subjective response to neuroleptics in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19(3):609–618. doi: 10.1093/schbul/19.3.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chouinard G, Margolese HC. Manual for the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS) Schizophr Res. 2005;76(2–3):247–265. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindenmayer J-P, Khan A, Eerdekens M, Van Hove I, Kushner S. Long-term safety and tolerability of long-acting injectable risperidone in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Eur Neuro Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(2):138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lloyd K, Latif MA, Simpson S, Shrestha KL. Switching stable patients with schizophrenia from depot and oral antipsychotics to long-acting injectable risperidone: efficacy, quality of life and functional outcome. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(3):243–252. doi: 10.1002/hup.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turner M, Eerdekens E, Jacko M, Eerdekens M. Long-acting injectable risperidone: safety and efficacy in stable patients switched from conventional depot antipsychotics. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;19(4):241. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000133500.92025.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Os J, Bossie CA, Lasser RA. Improvements in stable patients with psychotic disorders switched from oral conventional antipsychotics therapy to long-acting risperidone. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;19(4):229–232. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000122861.35081.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lasser RA, Bossie CA, Gharabawi GM, Kane JM. Remission in schizophrenia: results from a 1-year study of long-acting risperidone injection. Schizophr Res. 2005;77(2–3):215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin JLR, Pérez V, Sacristán M, et al. Meta-analysis of drop-out rates in randomised clinical trials, comparing typical and atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2006;21(1):11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]