Abstract

Recent technological advances have made it possible to identify and quantify thousands of proteins in a single proteomics experiment. As a result of these developments, the analysis of data has become the bottleneck of proteomics experiment. To provide the proteomics community with a user-friendly platform for comprehensive analysis, inspection and visualization of quantitative proteomics data we developed the Graphical Proteomics Data Explorer (GProX)1. The program requires no special bioinformatics training, as all functions of GProX are accessible within its graphical user-friendly interface which will be intuitive to most users. Basic features facilitate the uncomplicated management and organization of large data sets and complex experimental setups as well as the inspection and graphical plotting of quantitative data. These are complemented by readily available high-level analysis options such as database querying, clustering based on abundance ratios, feature enrichment tests for e.g. GO terms and pathway analysis tools. A number of plotting options for visualization of quantitative proteomics data is available and most analysis functions in GProX create customizable high quality graphical displays in both vector and bitmap formats. The generic import requirements allow data originating from essentially all mass spectrometry platforms, quantitation strategies and software to be analyzed in the program. GProX represents a powerful approach to proteomics data analysis providing proteomics experimenters with a toolbox for bioinformatics analysis of quantitative proteomics data. The program is released as open-source and can be freely downloaded from the project webpage at http://gprox.sourceforge.net.

During the last decade, identification and quantitation of proteomes has been facilitated by the constant developments in mass spectrometry instrumentation, fractionation techniques, quantitation-strategies, and data analysis software. Using state-of-the-art technology it has become possible to quantify several thousands of proteins (1–10), and even complete proteomes within a single proteomics experiment (11, 12). Powerful software solutions for protein identification and quantitation have been developed that allow users to process the information stored in the raw mass spectrometry data. These software solutions have been developed by both the scientific community (13–16) and by instrument vendors, exemplified by PEAKS (Bioinformatics Solutions) and Proteome Discoverer (Thermo Scientific). In face of these advances in the field, we find that data analysis is currently the bottleneck of proteomics experiments. Familiarity with several advanced bioinformatics tools, and preferably programming skills, are nowadays essential to perform a comprehensive analysis of large proteomics data sets (17). So far, experimenters without familiarity with computer programming have typically been required to use spreadsheet applications that are not per se developed for analysis of biological data and are therefore of limited use for working with the large amount of data produced from modern proteomics experiments. Alternatively a number of software solutions for analyzing “omics” data has been developed, notable examples are the MultiExperiment Viewer (18) which makes available algorithms for clustering and statistical analysis, and the GSEA-P (19), FatiGO+ (20), and DAVID (21) resources that focus on annotation and enrichment analysis of particularly Gene Ontology (GO) (22) terms. Tools such as QuPE (23), DAnTE (24), and StatQuant (25) provide a range of advanced statistical procedures for performing postquantitation analysis of protein abundance ratios. Finally, the Cytoscape (26) development team has delivered a remarkable contribution for the analysis of, in particular, protein-protein interaction data and protein network visualization.

Although these and other standalone tools are very useful for their specialized purposes, they do not support complex experimental setups and the divergent requirements for data input and output formats complicate interoperability and obstruct integration of several analysis steps. To allow experimenters to combine several individual tools, programs such as the Bioinformatic Resource Manager (27) and Prequips (28), which both use the program Gaggle (29) for data transfer, provide multifunctional platforms for data analysis. The Gaggle-based integrated solutions are powerful but particularly the divergent interfaces users are confronted with, might be challenging for nonspecialists. Finally, several commercial solutions are available, e.g. the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Ingenuity Systems) and ProteinCenter (Thermo Scientific/Proxeon). However, the high expenses associated with these programs and the intransparent nature of commercial software solutions might pose a significant obstacle to the application of these.

These issues led us to develop the Graphical Proteomics Data Explorer (GProX), a software package for comprehensive and integrated bioinformatics analysis and visualization of large proteomics data sets. The basic concept of GProX is to provide a data browsing environment similar to common spreadsheet applications and from this interface make available an array of functionalities for analyzing proteomics data. The major goal of GProX is thus to allow experimenters without specialized skills in bioinformatics to analyze their data and produce graphical representations to be used in scientific publications or presentations. GProX focuses on making available a wide array of useful analysis functions within a single platform and focuses particularly on a user-friendly interface and the production of high-quality graphical objects. The software, as well as the complete source code, is freely available for download from http://gprox.sourceforge.net.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

GProX Development Environment

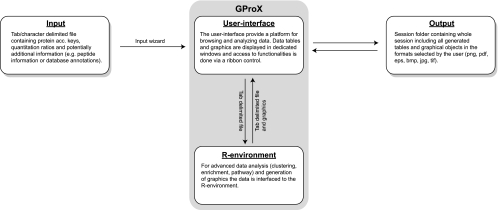

The overall structure and context of GProX is illustrated schematically in Fig. 1. The main program and the user interface are written in the Visual Basic programming language under the Microsoft .NET environment. The object-oriented architecture and the large selection of graphical objects available in the .NET environment allows creation of user-friendly graphical interfaces, which resemble common Microsoft Windows applications. Furthermore, the large repository of high-level functionalities implemented in .NET makes it an efficient platform for interfacing data and communicating with the operation system (OS). One drawback of the .NET environment is that it demands a Microsoft Windows OS. But because most, if not all, mass spectrometer vendors proprietary software is only available for Windows, most proteomics labs anyway require Windows systems for data generation and analysis.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the GProX Structure. GProX accepts as input a tab- or character-delimited file containing as a minimum only protein accession keys and quantitative information. Initial analysis session setup is done via a simple input wizard, which also supports defining the experimental design. The user interface provides access to all functions and uses the R-environment for advanced analyses and generation of graphics. All files associated with an analysis session are saved locally and from the session file a stored session can be opened for continued analysis.

Most of the features in GProX for data processing and generation of graphical objects are implemented as scripts written for R, the free software environment for statistical computing and graphics (30), see supplemental Fig. S1A. R has during recent years obtained increasing popularity for processing omics data, promoted especially by the rapidly growing number of add-in libraries available from the Bioconductor consortium (31). In addition, R is well suited for processing the large amounts of numerical data produced by quantitative proteomics experiments and contains a range of well-developed functions for generating simple as well as advanced graphical outputs in a number of formats. The interfacing between the .NET based user interface and R is achieved via tab-delimited files that are used as input for external R instances. After completion of the R-task, tab-delimited output files are interfaced back to the main program and graphical objects are saved locally and displayed in the main program. During normal operation the user is not confronted with the R tasks, which are executed as external processes in the background. Not least for debugging purposes, both standard and error output from the R-process is fed back into the main program and saved locally. All R functions implemented in GProX are collected in documented R packages (GProXutils, GProXplot, and GProXanalysis) which are distributed together with the program. These packages and their included functions can also be used directly or as a source of inspiration for experimenters familiar with R to modify or expand the functionalities currently implemented in GProX (see supplemental Methods and supplemental Fig. S1).

Requirements, Installation and Support

The GProX installer can be downloaded freely and without registration from the project website (http://gprox.sourceforge.net) as a self-installing executable file. The program requires a standard desktop computer with a contemporary Windows OS (we have tested the program on English versions of Windows XP and Windows7 32/64 bit) and version 3.5 or later of the .NET environment installed. Since the program depends critically on a working installation of R and several add-in libraries, these components must also be installed on the user's computer. During the first startup of GProX the user is prompted to download and install these components. To assist the user with this task we have included an automatic setup procedure. Also, detailed information about manual installation of R and add-in libraries is given in the GProX help. Furthermore, the whole installation procedure is described in detail in the tutorial distributed along with the program. For further support we have created a GProX Help Google group where users can post questions and comments. This group can be accessed from the project website or directly from http://groups.google.com/group/gprox.

Supported Data, Import and Output

The input format required by GProX is a tab- or character delimited file with column headers in the first row and each protein entry in separate rows. The minimum information present for each protein in the input file is the database accession key(s) and quantitative information. If needed, any additional information available from preceding data processing can also be imported from this input data file for subsequent applications within GProX. This additional information might be e.g. peptide information or database annotations such as Gene Ontology (22) or Pfam (32). As a consequence of this generic input format the application of GProX is not restricted to a particular mass spectrometry instrumentation platform, quantitation technique or data processing and quantitation software.

Import of data into GProX is done via an input wizard (see supplemental Fig. S2A) in which the user is requested to select the input file, specify the columns containing accession keys and quantitation ratios and finally, if required, specify the experimental setup. To specify the experimental setup, data columns containing quantitative data can be allocated to separate experiments. The arrangement of the experimental setup facilitates the analysis of more sophisticated quantitative proteomics experiments, where e.g. the temporal regulation patterns after different treatments are compared. In this case, a single experiment would include quantitation data from different time-points for one treatment condition. Multiple independent experiments can then be analyzed either separately or together and compared within GProX.

Upon creation of such a session, all information required to recreate a previous session is saved inside the session folder as a flat file (.gpx file) from which users can reload sessions to continue an analysis.

GProX employs a data management setup in which the input data file is regarded as a database, from which only columns specified are placed in a session data table containing only relevant information for data analysis. Other data columns from the input table can be imported on demand during analysis and is appended to the session table(s). Because of the fact that all data processing is performed only on the active session table, the processing efficiency is improved and, in addition, the original input file is left unchanged.

We have attempted to bring the graphics produced by GProX as close to a final state as possible, but users might want to fine-tune or layout their figures in an external graphics editor such as e.g. Adobe Illustrator or Corel Draw before using them for presentations or in publications. To this end, several output formats, including vector (eps, pdf) and bitmap (png, bmp, jpg, tif) graphics enable the user to open and freely modify figures in external applications.

GProX User Interface

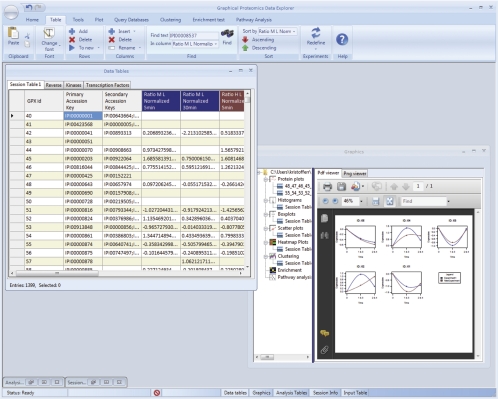

The main user interface of GProX is similar in appearance to that of spreadsheet programs as e.g. Open Office Calc or Microsoft Excel. All operations within the program are accessible via a ribbon control, menus, and dedicated dialog boxes (Fig. 2). The main user environment is a multiple-document interface containing up to five windows (supplemental Fig. S2B). The Session Info window contains all information about the current session, including a list of all produced tabular and graphical objects as well as an overview of the specified experimental setup. The Data Tables window contains the session tables as collection of tab-pages. Upon starting a new session, a single session table is created, but during the course of an analysis session the user can move subsets of this table to new session tables. Data analysis steps are performed only on the active tab-page, allowing the user to processes and analyze subsets of the complete data collection.

Fig. 2.

GProX User Interface. The multiple document user interface of GProX display, in dedicated windows, the data tables on which the analysis is performed, analysis results and all figures produced in the analysis session. All functions inside the program are accessible via a ribbon control (see also supplemental Fig. S1).

During the course of an analysis session a large collection of graphical objects can be created and these are displayed in a dedicated Graphics window. To navigate through the graphical objects the Graphics window contains an explorer panel to select displayable items and rename, delete, or move files. All tabular output from analysis steps is contained in the Analysis Tables window as tab page collection, similar to the Data Tables window. Finally, the input table can be displayed inside GProX, this however, serves mainly reference purposes, because the input table is solely used as a database without changing its content.

We have strived to make the software as intuitive and user-friendly as possible, but especially the more advanced analysis steps allow changing several associated parameters. To assist the user in selecting these parameters and to offer support in the basic use of the program, a compiled HTML help (chm) functionality and tooltip help boxes in individual dialogs assist in using the software. Furthermore, a step-by-step tutorial describing an example workflow in GProX is distributed along with the program to help the users getting started with the program.

Data Processing Algorithms

Details about processing algorithms and data analysis strategies are described in the supplemental methods and outlined in supplemental Figs. S4 to S6.

RESULTS

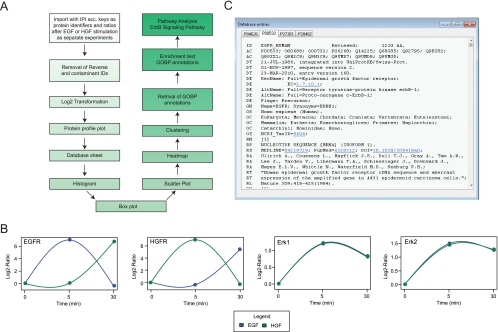

To demonstrate the features of GProX, a previously published quantitative proteomics data set comparing phospho-Tyrosine dependent signaling 5 and 30 min after epidermal growth factor (EGF) or hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) stimulation (33) was used (the experimental setup is summarized in supplemental Fig. S3). To analyze these data sets, the data was imported to GProX specifying the IPI accession keys as protein identifiers and corresponding columns containing the quantitation ratios after EGF or HGF stimulation were allocated to two separate experiments. An overview of the analysis steps outlined in the following sections is illustrated in Fig. 3A.

Fig. 3.

Analysis steps, Protein Dynamics and Database Information within GProX. A, Overview of the analysis steps performed to exemplify the application of GProX for analyzing quantitative proteomics data. B, Plots of the ratios of one or more proteins and experiments can readily be requested to acquire a rapid overview of protein regulation. In this case, each panel includes regulation profiles from different experiments for individual proteins. C, IPI- and UniProt database sheets can be readily requested for selected proteins to immediately provide the user with available information stored in these databases. Furthermore, these database entries link out to other primary resources or higher-level annotations.

Data Organization and Inspection

One main goal of GProX is to provide a comfortable environment for browsing quantitative proteomics data in a spreadsheet-like fashion. Basic functions such as sort, find, deletion or insertion of rows and columns as well as arithmetic operations as e.g. summing or averaging over entire columns support organization and modification of experimental data. In this regard, data subsets can also be allocated to new data tables, providing data grouping based on e.g. functional categories or regulation. Furthermore, the experimental setup defined during data import can be easily modified in the course of an analysis session, e.g. to compare experimental properties or to account for data processing within GProX.

Quantitative data in the form of intensity ratios often requires transformation to other scales. With GProX logarithmic, square root and inverse transformations can be readily performed. From the sample data set reverse hits (used to determine false discovery rate (13, 34)) and common contaminant identifications like trypsin, bovine serum albumin and keratins were moved to a separate table and the remaining protein quantitations were Log2 transformed.

One strong feature in GProX is its on-the-fly plotting function, where the quantitation data from one or more proteins can be displayed as line diagrams (Fig. 3B). This is very helpful, as it gives a quick overview of regulation patterns of selected proteins and differences of treatment conditions. Here, if more than one protein is selected and there is more than one experimental condition defined, quantitative data can be plotted in two different ways: (1) one plot is generated for each selected protein, including all experimental conditions or (2) one plot is generated for each experimental condition, each plot containing data from all selected proteins for this condition. To exemplify the plotting function we show in Fig. 3B the regulation of key growth factor signaling proteins. From these plots it is striking that although the receptor proteins EGFR and HGFR are regulated oppositely between the stimulations, a very similar regulation is observed for the key effector kinases ERK1/2.

Often it is also required to obtain immediately all available information from a given protein. Therefore, complete International Protein Index (35) and UniProt (36) database sheets, which link out to further information sources, can be promptly displayed for the proteins of interest (Fig. 3C).

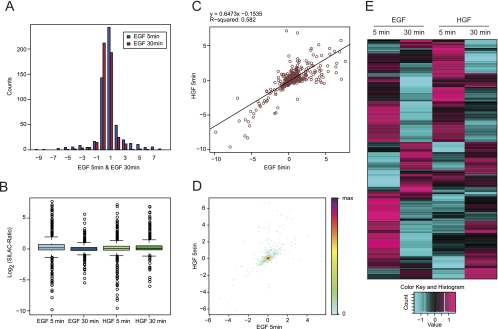

Visualization of Data Distributions

To evaluate the distribution of quantitative data, GProX provides a palette of different visualizations. These plots can be highly customized to allow the users to visualize keys features of their quantitative data. Histograms, box plots, scatter plots, and density plots can be easily produced for this purpose to assess or compare protein regulation and evaluate the reproducibility of replicate experiments (Fig. 4A to 4D). For example, the histogram in Fig. 4A indicates that, although the majority of proteins are not regulated, the distribution of quantitation ratios is shifted to higher values at the early 5 min time point, compared with the prolonged stimulation for 30 min. Heatmaps summarizing the complete set of quantitation ratios in one diagram can provide a comprehensive overview of protein regulation across experimental conditions (Fig. 4E). Finally, descriptive statistics can be readily requested for all data columns to further assist in acquiring an overview of the data.

Fig. 4.

Visualization of Data Distributions in GProX. Graphical overviews of the distribution of protein abundance ratios in the form of histograms (A), box plots (B), scatter plots (C), density scatter plots (D), and heatmaps (E). Individually or in combination, the visualizations provide a summary of the cumulative properties of the data, which is indispensable e.g. for comparing experiments or assessing the reproducibility of replicate experiments.

Clustering Analysis

Regulation patterns most often reflect distinct involvement of the proteins in the corresponding cellular pathway and could therefore be used to hint toward possible functional roles of these proteins. To find coregulated proteins with similar regulation patterns, unsupervised clustering is a popular and powerful approach. By performing this useful bioinformatic exercise, a comprehensible number of protein groups with similar quantitation patterns can be obtained. In GProX unsupervised clustering based on the fuzzy c-means algorithm (37) has been implemented (see supplemental Fig. S4 for details). Fuzzy c-means clustering is very suitable for clustering of quantitative proteomics data as it, in contrast to the related k-means clustering, associates each entry to a cluster with a given likelihood, the membership value. The membership values are used to assess how well a given entry fits the consensus profile and allows color coding cluster graph items according to their goodness of fit to the cluster consensus profile.

The cluster analysis can be customized by the user with parameters for e.g. the number of clusters, number of algorithm iterations, color-scheme, and specification of regulation threshold, standardization and graphical properties. To exemplify the output of the clustering module, we subjected the example data set to clustering and the result clearly indicates that the proteins in the data set can be partitioned into groups with distinct patterns of regulation, corresponding to different responses to the growth factor stimulation (Fig. 5A). For example early components of growth factor signaling pathways such as the receptors are found in cluster 5, whereas a number of downstream components as GTPases and kinases can be found in clusters 4 and 6. An additional value of cluster analysis is that it can serve as a base for subsequent identification of features distinguishing proteins with a given regulation pattern as exemplified in the following sections.

Fig. 5.

Clustering and Enrichment Analysis in GProX. A, Unsupervised clustering by fuzzy-c means of the example data revealing distinct patterns of regulation. B, Enrichment analysis for GO biological process terms over-represented in each cluster (see fig. 5A). From this analysis it is clear, that the different modes of regulation summarized in (A) correspond also to distinct cellular processes.

Batch Database Retrieval

The many databases maintained by the scientific community provide a wealth of information about protein function, structure, modifications, sequence, and genetic context, and are of immense value when analyzing proteomics data. To allow extraction of up-to-date annotations for all proteins in the data table GProX retrieves information from IPI (35), UniProt (36), or Ensembl (38) databases using the BioMart (39) and DBfetch services provided by the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI). In this way the numerous protein annotations stored and regularly updated in these databases can be extracted and appended directly to the data tables. This information can assist the experimenter in obtaining an overview of protein function, but can also provide the basis for functional grouping of proteins or analysis of the occurrence of over-represented features in groups of proteins. In addition to providing the user with the option to select the database from which to retrieve annotations, the database information can be extracted with accession keys apart from the input keys. If more than one key is associated with a protein, peptide counts can be used to filter which keys to use for the database query. For the example data set we first translated the IPI identifier to UniProt accession keys and used these to retrieve the GO biological process annotations (22) from the UniProt database.

Feature Enrichment Analysis

To approach whether particular features, such as GO terms or structural domains, are descriptive for the regulated proteins or proteins in a given cluster, GProX incorporates a module that can be used to evaluate enrichment of features in subsets of the data (supplemental Fig. S5). The module can be used to test for enrichment of any feature present in the data table. In this way the module is essentially generic in terms of the explored features and the enrichment analysis can be performed using a range of statistical test and p value adjustment algorithms. The hierarchical structure of the GO annotations can be used to filter for the most descriptive terms, which best describe the properties of the data.

The output of the enrichment test is a tabular summary as well as a graphical overview of the analysis. The tabular output provides details about the occurrences and p values for enriched annotations. The type of graphical output depends on the way the test is performed. In the simplest case were the test is for particular features prevalent in the regulated proteins a bar plot is produced which summarizes the frequency of the enriched features within the regulated and not-regulated proteins. Alternative, the analysis can test whether a given feature is enriched in a particular cluster from a preceding clustering analysis in which case a heatmap is generated, showing in which cluster individual feature annotations are enriched. For the example data set the GO biological process annotations were used to get an overview of their occurrence in each of the clusters. As observed from Fig. 5B enrichment of a number of terms relating to growth factor signaling are found in clusters 5 and 6.

The easy accessibility of both clustering, annotation retrieval and enrichment analysis allow the user, even in an early stage of data analysis, to obtain a valuable overview of protein regulation and association of cellular processes with these regulation patterns. These analyses might serve as a guideline e.g. to identify groups of proteins to be targeted in follow-up experiments.

Pathway Analysis

In biological systems proteins often exert their function not as independent entities but as members of multi-protein complexes or signal transduction pathways, both of which can be efficiently analyzed by quantitative proteomics (40–43). A powerful way of summarizing protein regulation is therefore to display it in the context of signal transduction, metabolic pathways or multiprotein complexes. GProX offer the possibility to map protein quantitation values to the signaling pathway and multimolecular structure information maintained by the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (44) (supplemental Fig. S6). Allocation of proteins can be either to selected pathways or to significantly perturbed pathways from the large KEGG pathway repository. To identify significantly perturbed pathways GProX relies on the signaling pathway impact analysis (SPIA) algorithm implemented in the SPIA package for R (45). We find this algorithm well suited since it besides assessing enrichment of pathways also incorporates information on pathway perturbation and the topology of individual pathways when calculating a p value. If significant hits are obtained for the SPIA algorithm, a table summarizing the result of the analysis is provided and regulation values are mapped to all significant pathways. This color coding of pathway nodes (proteins) can be done in two different ways, either the regulation values of nodes are indicated in a gradient from low to high or the cluster annotation of identified proteins in the pathway is displayed. Although coloring the pathway nodes with a simple gradient provides a comprehensive overview of the regulation, the possibility of coloring the pathways by cluster membership enables the user to illustrate e.g. a more elaborate time-course profile. In Fig. 6 the regulation after 30 min of EGF stimulation is mapped onto the ErbB signaling pathway. From this figure one can see that some of the proteins upstream in the pathway have either returned to the control level or are down-regulated, whereas downstream effectors as Erk and Abl are still active at this later time point. For comparison see supplemental Fig. S7, where the regulation after 5 min EGF stimulation shows up-regulation of proteins upstream in the pathway and the cluster information mapped to the pathway.

Fig. 6.

GProX Pathway Analysis of the Cellular Response to EGF Stimulation. The regulation after 30 min stimulation with EGF was mapped to the ErbB KEGG signaling pathway. Nodes corresponding to proteins identified in the example data are color-coded according to regulation so up-regulated proteins are colored in shades of red, down-regulated proteins are colored in shades of blue and not regulated proteins are gray. This analysis illustrate that after 30 min of EGF stimulation the proteins upstream in the pathway have returned to the control state or are down-regulated while downstream effector proteins remain up-regulated.

DISCUSSION

We have outlined the structure and features of GProX and, using an example data set, exemplified a typical workflow. It is not possible to describe here all features and applications in detail but we believe that GProX is amply versatile to allow the users to customize their analyses and to extract a wealth of information from their rich quantitative proteomics data. It is our hope that the range of functionalities provided within a single platform accessible for nonspecialist can serve both as a comfortable platform for data browsing and also as a toolbox for scrutinizing the properties of quantitative proteomics data. This being said, it is evident that it is beyond the scope of one software solution to incorporate all the specialized features of the programs described in the introduction, but we find that GProX provides a powerful hub in the analysis of quantitative proteomics data.

In our opinion the current status of software for bioinformatics analysis subsequent to quantitation is lagging behind the rapid technical improvements in proteomics. Therefore we hope that GProX may provide a contribution to the ongoing development in the field and help experimenters to overcome hurdles in their bioinformatics analysis.

Acknowledgments

We thank all CEBI members for comments and helpful discussions; Jörn Dengjel, Yasushi Ishihama, Irina Kratchmarova, Marcus Kruger, Jesper Olsen, and Shao-En Ong for in-advance testing; Dean Hammond and Michael Clague for the example data set.

Footnotes

* The work was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation (B. B. - Junior Group Leader Fellowship), the Danish Natural Science Research Council and the European Commission's 7th Framework Programme (HEALTH-F4-2008-201648/PROSPECTS). J. T. V. is supported by an EMBO Long Term Fellowship (ALTF 1267-2009).

This article contains supplemental Methods, References, and Figs. S1 to S7.

This article contains supplemental Methods, References, and Figs. S1 to S7.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- GProX

- Graphical Proteomics Data Explorer

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor

- GO

- Gene Ontology

- HGF

- hepatocyte growth factor

- KEGG

- Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- OS

- operating system

- SPIA

- Signaling Pathway Impact Analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rigbolt K. T., Prokhorova T. A., Akimov V., Henningsen J., Johansen P. T., Kratchmarova I., Kassem M., Mann M., Olsen J. V., Blagoev B. (2011). System-wide temporal characterization of the proteome and phosphoproteome of human embryonic stem cell differentiation. Sci. Signal. 4, rs3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dengjel J., Kratchmarova I., Blagoev B. (2009) Receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: a view from quantitative proteomics. Mol. Biosyst. 5, 1112–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Swaney D. L., Wenger C. D., Coon J. J. (2010) Value of using multiple proteases for large-scale mass spectrometry-based proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 9, 1323–1329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peng J., Schwartz D., Elias J. E., Thoreen C. C., Cheng D., Marsischky G., Roelofs J., Finley D., Gygi S. P. (2003) A proteomics approach to understanding protein ubiquitination. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 921–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Usaite R., Wohlschlegel J., Venable J. D., Park S. K., Nielsen J., Olsson L., Yates J. R., Iii (2008) Characterization of global yeast quantitative proteome data generated from the wild-type and glucose repression saccharomyces cerevisiae strains: the comparison of two quantitative methods. J. Proteome Res. 7, 266–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aye T. T., Scholten A., Taouatas N., Varro A., Van Veen T.A., Vos M. A., Heck A. J. (2010) Proteome-wide protein concentrations in the human heart. Mol. Biosyst. 6, 1917–1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Prokhorova T. A., Rigbolt K. T., Johansen P. T., Henningsen J., Kratchmarova I., Kassem M., Blagoev B. (2009) Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) and quantitative comparison of the membrane proteomes of self-renewing and differentiating human embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 959–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kristensen A. R., Schandorff S., Høyer-Hansen M., Nielsen M. O., Jäättelä M., Dengjiel J., Andersen J. S. (2008). Ordered organelle degradation during starvation-induced autophagy. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 7, 2419–2428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iwasaki M., Miwa S., Ikegami T., Tomita M., Tanaka N., Ishihama Y. (2010). One-dimensional capillary liquid chromatographic separation coupled with tandem mass spectrometry unveils the Escherichia coli proteome on a microarray scale. Anal. Chem. 82, 2616–2620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rigbolt K. T., Blagoev B. (2010) Proteome-wide quantitation by SILAC. Methods Mol. Biol. 658, 187–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de, Godoy L. M., Olsen J. V., Cox J., Nielsen M. L., Hubner N. C., Fröhlich F., Walther T. C., Mann M. (2008) Comprehensive mass-spectrometry-based proteome quantification of haploid versus diploid yeast. Nature 455, 1251–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Picotti P., Bodenmiller B., Mueller L. N., Domon B., Aebersold R. (2009) Full dynamic range proteome analysis of S. cerevisiae by targeted proteomics. Cell 138, 795–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cox J., Mann M. (2008) MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matthiesen R., Trelle M. B., Højrup P., Bunkenborg J., Jensen O. N. (2005) VEMS 3.0: algorithms and computational tools for tandem mass spectrometry based identification of post-translational modifications in proteins. J. Proteome Res. 4, 2338–2347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mortensen P., Gouw J.W., Olsen J. V., Ong S. E., Rigbolt K. T., Bunkenborg J., Cox J., Foster L. J., Heck A. J., Blagoev B., Andersen J. S., Mann M. (2010) MSQuant, an open source platform for mass spectrometry-based quantitative proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 9, 393–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deutsch E. W., Mendoza L., Shteynberg D., Farrah T., Lam H., Tasman N., Sun Z., Nilsson E., Pratt B., Prazen B., Eng J. K., Martin D. B., Nesvizhskii A. I., Aebersold R. (2010) A guided tour of the Trans-Proteomic Pipeline. Proteomics 10, 1150–1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kumar C., Mann M. (2009) Bioinformatics analysis of mass spectrometry-based proteomics data sets. FEBS Lett. 583, 1703–1712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saeed A. I., Bhagabati N. K., Braisted J. C., Liang W., Sharov V., Howe E. A., Li J., Thiagarajan M., White J. A., Quackenbush J. (2006) TM4 microarray software suite. Methods Enzymol. 411, 134–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Subramanian A., Kuehn H., Gould J., Tamayo P., Mesirov J.P. (2007) GSEA-P: a desktop application for Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. Bioinformatics 23, 3251–3253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Al-Shahrour F., Minguez P., Tárraga J., Medina I., Alloza E., Montaner D., Dopazo J. (2007) FatiGO +: a functional profiling tool for genomic data. Integration of functional annotation, regulatory motifs and interaction data with microarray experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W91–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dennis G., Jr., Sherman B. T., Hosack D. A., Yang J., Gao W., Lane H. C., Lempicki R. A. (2003) DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 4, P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ashburner M., Ball C. A., Blake J. A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J. M., Davis A. P., Dolinski K., Dwight S. S., Eppig J. T., Harris M. A., Hill D. P., Issel-Tarver L., Kasarskis A., Lewis S., Matese J. C., Richardson J. E., Ringwald M., Rubin G. M., Sherlock G. (2000) Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Albaum S. P., Neuweger H., Fränzel B., Lange S., Mertens D., Trötschel C., Wolters D., Kalinowski J., Nattkemper T. W., Goesmann A. (2009) Qupe–a Rich Internet Application to take a step forward in the analysis of mass spectrometry-based quantitative proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics 25, 3128–3134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Polpitiya A. D., Qian W. J., Jaitly N., Petyuk V. A., Adkins J. N., Camp D. G., 2nd, Anderson G. A., Smith R. D. (2008) DAnTE: a statistical tool for quantitative analysis of -omics data. Bioinformatics 24, 1556–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van Breukelen B., van den Toorn H. W., Drugan M. M., Heck A. J. (2009) StatQuant: a post-quantification analysis toolbox for improving quantitative mass spectrometry. Bioinformatics 25, 1472–1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N. S., Wang J. T., Ramage D., Amin N., Schwikowski B., Ideker T. (2003) Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shah A. R., Singhal M., Klicker K. R., Stephan E. G., Wiley H. S., Waters K. M. (2007) Enabling high-throughput data management for systems biology: the Bioinformatics Resource Manager. Bioinformatics 23, 906–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gehlenborg N., Yan W., Lee I. Y., Yoo H., Nieselt K., Hwang D., Aebersold R., Hood L. (2009) Prequips–an extensible software platform for integration, visualization and analysis of LC-MS/MS proteomics data. Bioinformatics 25, 682–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shannon P. T., Reiss D. J., Bonneau R., Baliga N. S. (2006) The Gaggle: an open-source software system for integrating bioinformatics software and data sources. BMC Bioinformatics 7, 176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. R Development Core Team (2010). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, http://www.R-project.org

- 31. Gentleman R. C., Carey V. J., Bates D. M., Bolstad B., Dettling M., Dudoit S., Ellis B., Gautier L., Ge Y., Gentry J., Hornik K., Hothorn T., Huber W., Iacus S., Irizarry R., Leisch F., Li C., Maechler M., Rossini A. J., Sawitzki G., Smith C., Smyth G., Tierney L., Yang J. Y., Zhang J. (2004) Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 5, R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Finn R. D., Mistry J., Tate J., Coggill P., Heger A., Pollington J. E., Gavin O. L., Gunasekaran P., Ceric G., Forslund K., Holm L., Sonnhammer E. L., Eddy S. R., Bateman A. (2010) The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D211–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hammond D. E., Hyde R., Kratchmarova I., Beynon R. J., Blagoev B., Clague M. J. (2010) Quantitative analysis of HGF and EGF-dependent phosphotyrosine signaling networks. J. Proteome Res. 9, 2734–2742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Elias J. E., Gygi S. P. (2007) Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 4, 207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kersey P. J., Duarte J., Williams A., Karavidopoulou Y., Birney E., Apweiler R. (2004) The International Protein Index: an integrated database for proteomics experiments. Proteomics 4, 1985–1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. UniProt Consortium (2010) The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) in 2010. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D142–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Futschik M. E., Carlisle B. (2005) Noise-robust soft clustering of gene expression time-course data. J. Bioinform. Comput. Biol. 3, 965–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Flicek P., Amode M. R., Barrell D., Beal K., Brent S., Chen Y., Clapham P., Coates G., Fairley S., Fitzgerald S., Gordon L., Hendrix M., Hourlier T., Johnson N., Kähäri A., Keefe D., Keenan S., Kinsella R., Kokocinski F., Kulesha E., Larsson P., Longden I., McLaren W., Overduin B., Pritchard B., Riat H. S., Rios D., Ritchie G. R., Ruffier M., Schuster M., Sobral D., Spudich G., Tang Y. A., Trevanion S., Vandrovcova J., Vilella A. J., White S., Wilder S. P., Zadissa A., Zamora J., Aken B. L., Birney E., Cunningham F., Dunham I., Durbin R., Fernandez-Suarez X. M., Herrero J., Hubbard T. J., Parker A., Proctor G., Vogel J., Searle S. M. (2011) Ensembl 2011. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D800–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Durinck S., Moreau Y., Kasprzyk A., Davis S., De Moor B., Brazma A., Huber W. (2005) BioMart and Bioconductor: a powerful link between biological databases and microarray data analysis. Bioinformatics 21, 3439–3440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Choudhary C., Mann M. (2010) Decoding signalling networks by mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 427–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vermeulen M., Hubner N. C., Mann M. (2008) High confidence determination of specific protein-protein interactions using quantitative mass spectrometry. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 19, 331–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Blagoev B., Ong S. E., Kratchmarova I., Mann M. (2004) Temporal analysis of phosphotyrosine-dependent signaling networks by quantitative proteomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 1139–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dengjel J., Kratchmarova I., Blagoev B. (2010) Mapping protein-protein interactions by quantitative proteomics. Methods Mol. Biol. 658, 267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kanehisa M., Goto S., Furumichi M., Tanabe M., Hirakawa M. (2010) KEGG for representation and analysis of molecular networks involving diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D355–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tarca A. L., Draghici S., Khatri P., Hassan S. S., Mittal P., Kim J. S., Kim C. J., Kusanovic J. P., Romero R. (2009) A novel signaling pathway impact analysis. Bioinformatics 25, 75–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]