Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the host response to systemically administered lipid nanoparticles (NPs) encapsulating plasmid DNA (pDNA) in the spleen using a DNA microarray. As a model for NPs, we used a multifunctional envelope-type nano device (MEND). Microarray analysis revealed that 1,581 of the differentially expressed genes could be identified by polyethylene glycol (PEG)-unmodified NP using a threefold change relative to the control. As the result of PEGylation, the NP treatment resulted in the reduction in the expression of most of the genes. However, the expression of type I interferon (IFN) was specifically increased by PEGylation. Based on the microarray and a pathway analysis, we hypothesize that PEGylation inhibited the endosomal escape of NP, and extended the interaction of toll-like receptor-9 (TLR9) with CpG-DNA accompanied by the production of type I IFN. This hypothesis was tested by introducing a pH-sensitive fusogenic peptide, GALA, which enhances the endosomal escape of PEGylated NP. As expected, type I IFN was reduced and interleukin-6 (IL-6) remained at the baseline. These findings indicate that a carrier design based on microarray analysis and the manipulation of intracellular trafficking constitutes a rational strategy for reducing the host immune response to NPs.

Introduction

The success of clinical gene therapy greatly depends on the development not only of efficient but also safe gene delivery systems.1 Because of the ease of large-scale production and lack of a specific immune response unlike viral vectors, various types of nonviral gene delivery systems such as lipoplexes, polyplexes, and micelles have been developed, in attempts to improve the efficiency of in vivo gene expression.2,3,4 However, innate immune responses are induced by the systemic administration of a lipoplex.5 Unmethylated CpG motifs of plasmid DNA in a lipoplex have been reported to stimulate the innate immune response by interacting with host toll-like receptor-9 (TLR9), expressed in endosomes, and to trigger the release of inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-12, and type I interferon (IFN).6 It was reported that a lipoplex containing either methylated CpG or non-CpG plasmid DNA (pDNA) reduced cytokine production, but the reduction was not complete.5,7,8 Furthermore, cytokine production was not completely abolished in TLR9−/− mice after an intravenous (i.v.) administration of a lipoplex or in primary cultured macrophages from TLR9−/− mice after lipoplex treatment.7,9 DNA-dependent activator of IFN-regulatory factor (DAI) has been identified as a cytosolic DNA sensor.10 DAI, also known as Z-DNA binding protein-1 (ZBP1), recognizes double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) in a CpG-independent manner, which causes an TLR9-independent innate immune response.11 These findings suggest that the immune reaction to a lipoplex is more complicated than previously thought. This appears to be true for viral vectors12 as well, and an understanding of host responses to the systemic administration of a lipoplex is necessary for the successful and efficacious development of in vivo gene delivery systems. However, examining the production of certain types of cytokines after i.v. administration is not sufficient to guarantee the safety of a gene delivery system.

To address and solve this issue, gene expression profiling represents a promising approach to understanding the underlying mechanism of host responses.13,14,15,16,17,18,19 Kay and coworkers reported that a DNA microarray-based comparison of the host response to adenoviral (Ad) and adeno-associated viral vectors revealed that the host recognition of capsid and DNA of adeno-associated viral is different from that of Ad.13 This approach has been also applied to nonviral vectors in the form of toxicogenomics studies.16,17,18,19 In the case of a polypropylenimine dendrimer based DNA complex, a microarray analysis revealed that gene expression in culture cells was altered by the generation of the dendrimer, and was dependent on the cell lines.16 However, the response of a host to a systemically administrated nonviral gene vector has not been examined using this approach.

We recently developed a novel lipid nanoparticle (NP), a multifunctional envelope-type nano device (MEND), in which pDNA is condensed with a polycation, followed by encapsulation with a lipid envelope.20 In this study, an analysis of splenic expression profiles in mice was conducted after the intravenous injection of MENDs as an NP model, using a whole-genome DNA microarray. Since the spleen is the largest secondary lymphoid organ and contains tissue macrophages that are associated with an immune response after an intravenous injection of a lipoplex.21 It was hypothesized that modification with PEG would confer biocompatibility for nonviral vectors, resulting in an improved safety.22 It would permit us to predict whether PEGylation would change the gene expression profile by NP administration for the better. However, since only a few studies of the effect of PEGylation on host response have appeared, detailed information on the influence of PEGylation is not available. Therefore, we attempted to elucidate the effect of the PEGylation of NP (PEG-NP) on the host response.

Results

Characterization of NPs

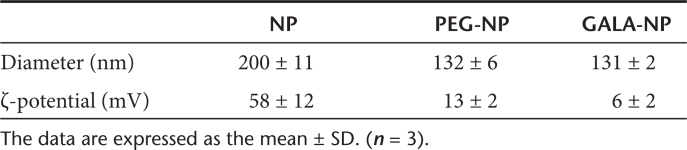

The average diameter and ζ-potential of the condensed pDNA/polyethyleneimine (PEI) complex particles were ~80 nm and −50 mV, respectively. The average diameters and ζ-potentials of the prepared NPs are summarized in Table 1. The PEG-unmodified NP was around 200 nm in diameter, and was highly positively charged due to the presence of a cationic lipid. PEG modification (PEG-NP) reduced the diameter of the NP and the positive charge was decreased, compared to an unmodified NP, as the result of the formation of a stable lamellar structure with a larger curvature and masking of the surface of the lipid envelope by the aqueous layer of the PEG moiety.23 Modification of PEG-NP with chol-GALA (GALA-NP) slightly reduced the ζ-potential of the NP since GALA contains negatively charged glutamic acid residues, but it had no influence on the diameter.

Table 1. Physical properties of the prepared nanoparticles.

Microarray data analysis

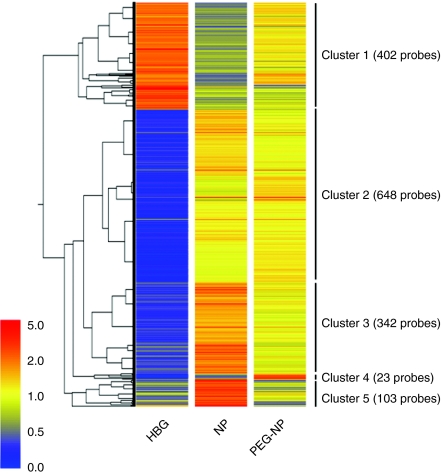

To understand what occurs in a host following the systemic administration of an NP and a PEG-NP, splenic gene expression profiles in mice were generated using whole-genome oligonucleotide microarrays. The spleen is the largest secondary lymphoid organ and is associated with the immune response.21 Mice were injected via the tail vein with HEPES-buffered glucose (HBG), NP, or PEG-NP. After 2 hour, the spleen was collected and RNA prepared from the tissues, microarrays were then hybridized, as described in the Materials and Methods section. Using a threefold change relative to the HBG treatment as a criterion for differential expression, 1,581 genes were extracted from the administration of NP. A clustergram of these 1,581 genes is shown in Figure 1. The downregulated 402 genes resulting from the NP treatment, compared to HBG were classified in cluster 1, and the other 1,179 genes, which were upregulated by the NP treatment, were classified into clusters 2–5. In clusters 1, 3, and 5 (55.8%), the variation in gene expression as the result of the PEG-NP treatment were reduced compared to the corresponding value for NP, suggesting that PEGylation reduces the biological stimulation of NP after systemic administration. On the other hand, the gene expression in cluster 2 showed subtle alterations between NP and PEG-NP (42.7%). PEG-NP unexpectedly caused an increase in gene expression compared to NP, as shown in cluster 4 (1.5%).

Figure 1.

Clustergram of genes that are differentially regulated by administration of nanoparticles (NPs). 1,581 genes with an expression ratio of NP to HEPES-buffered glucose (HBG) >3 or <0.33 are represented. 402 genes were downregulated after NP administration, classified in cluster 1. The remaining 1,179 genes were upregulated, classified in clusters 2–5. Red, yellow, and blue represent relative gene expression among HBG, NP, and PEGylation of NP (PEG-NP).

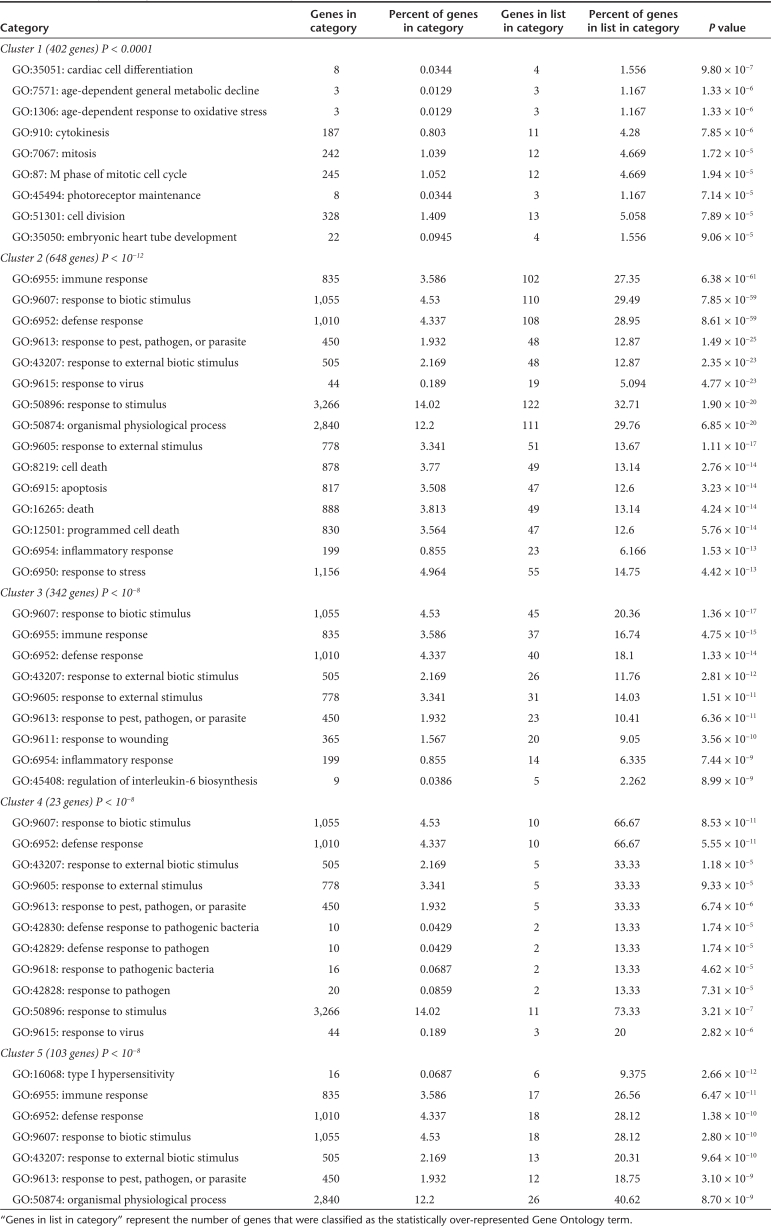

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis is used to identify the molecular pathways and describe the biological processes of the transcript profiling data. Based on the GO analysis, the GO terms of “biological process” that were significantly over-represented in each cluster are shown in Table 2. The GO terms of the downregulated genes are related to cell division such as “cytokinesis,” “mitosis,” “M phase of mitotic cell cycle,” differentiation and metabolism. On the other hand, the majority of GO terms for the upregulated genes in clusters 2–5 are mainly associated with “immune response,” “response to biotic stimulus,” “defense response,” and related processes, which are generally associated with the immune system. These observations indicate that the characteristics of the upregulated genes and downregulated genes resulting from the NPs treatment were completely different.

Table 2. Statistically over-represented GO terms (biological Process) in each cluster.

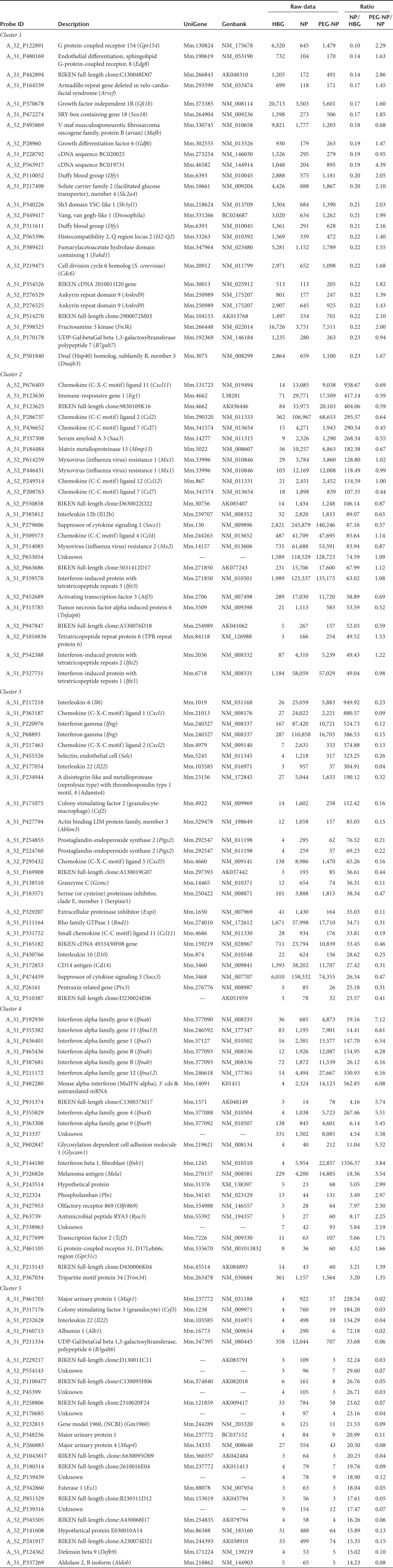

We further listed the top 25 genes in order of greatly altered expression level by the NP treatment compared with HBG in each cluster, as shown in Table 3. The ratios of the gene expression level of PEG-NP/NP in clusters 1, 3, and 5 were improved, and the ratios in cluster 2 were comparable. However, the ratios for PEG-NP/NP in cluster 4 were greatly enhanced. In cluster 3, inflammatory cytokines such as Il6 and Ifng are ranked higher with significantly lower levels of expression in the PEG-NP treatment compared to NP. As shown in Table 3, Ifna subtypes and Ifnb, classified as type I IFN, are specifically located in cluster 4.

Table 3. Genes that are differentially expressed in response to nanoparticle treatment in each cluster.

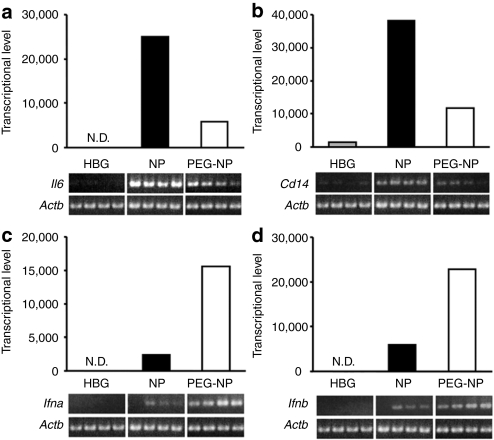

Quantification of mRNA level in spleen and cytokine level in serum

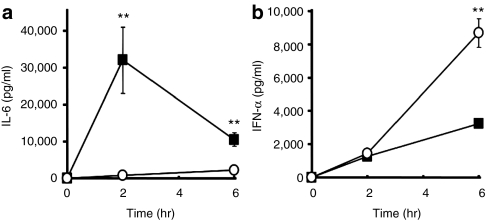

To verify that mRNA levels are elevated in the spleen, the mRNA expression of Il6, Cd14, located in cluster 3, and Ifna and Ifnb, located in cluster 4, the genes were further evaluated by quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR). As shown in Figure 2, the semiquantitative RT-PCR results were in good agreement with the expression information from the microarray analysis, confirming that these genes are actually upregulated after NP or PEG-NP administration. We next assessed the levels of IL-6 and IFN-α in serum at 2 and 6 hour after an i.v. injection of NP and PEG-NP. As shown in Figure 3a, NP induced the production of IL-6, and PEGylation markedly reduced the serum levels of IL-6. On the other hand, the serum level of IFN-α in the case of PEG-NP was equal or greater than that for NP. These observations were correlated with the amount of mRNA in the spleen, as evidenced by microarray analysis and quantitative PCR (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Transcriptional levels obtained by microarray were in agreement with mRNA quantities by quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR (qRT-PCR). Bars represent transcriptional levels of (a) interleukin-6 (Il6), (b) Cd14, (c) interferon Ifna, and (d) Ifnb obtained by microarray analysis. Gene expressions were confirmed by semiquantitative RT-PCR as shown in electrophoretic images. qRT-PCR results were in good agreement with the microarray analysis. HBG, HEPES-buffered glucose; NPs, nanoparticles; PEG-NP, PEGylation of NP.

Figure 3.

Serum levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interferon (IFN)-α after treatment of nanoparticle (NP) and polyethylene glycol (PEG). Each sample (25 µg plasmid DNA (pDNA)/mouse) was intravenously injected at a normal pressure. At 2 and 6 hours after the intervenous injection (a) serum IL-6 and (b) IFN-α were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISA). (a) Nanoparticle (NP) (closed squares) enhanced IL-6 production, and PEGylation (open circles) effectively reduced it. (b) On the other hand, PEGylation (open circles) stimulated IFN-α compared to NP (closed squares). Neither IL-6 nor IFN-α were detected in the HEPES-buffered glucose (HBG) treatment. These values are in good agreement with the microarray and reverse transcriptase-PCR results. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 4). **P < 0.01. PEG-NP, PEGylation of NP.

Pathway analysis and the effect of the acceleration of endosomal escape of PEGylated NP by GALA on type I IFN production

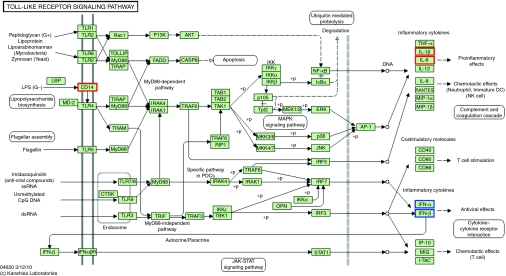

Based on the microarray analysis, PEGylation generally reduced the biological reaction to systemically administered NP. However, contrary to our expectations, PEGylation stimulated the production of type I IFN. To identify the mechanism underlying this, we performed a pathway analysis. According to the GO analysis and a subsequent quantitative determination of mRNA in the spleen, immune stimulation constituted a major biological reaction in the host after the systemic administration of NP. Since members of the TLR family are essential components in the CpG-mediated immune response, we focused on TLR pathway signaling using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes database. As shown in Figure 4, IL-6, IL-1β, and CD14, located in cluster 3 (red) and IFN-α and IFN-β, located in cluster 4 (blue) fall into TLR signaling pathway.

Figure 4.

Differentially expressed genes in the toll-like receptor signaling pathway from Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways. Red and blue columns represent differentially expressed genes located in cluster 3 and cluster 4, respectively.

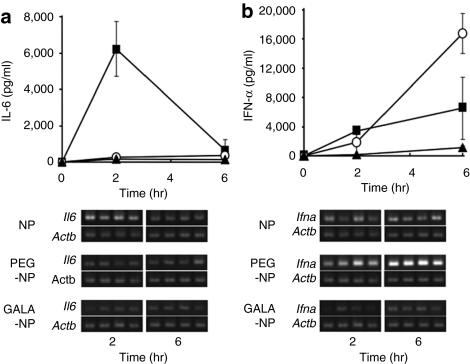

As described above, PEGylation confers biocompatibility and safety for NPs. On the other hand, it was reported that the modification of NP with PEG crucially inhibits the endosomal escape of NP,24,25 resulting in a reduced activity of the cargo. We assumed that endosomal trapping triggered the excessive interaction of the pDNA encapsulated in PEG-NP with TLR9 following destabilization and digestion of the PEG-NP in endosomes/lysosomes, which resulted in an enhanced type I IFN production. We previously demonstrated that a pH-sensitive fusogenic peptide, GALA promoted the endosomal escape of PEGylated NP, which resulted in enhanced gene expression and silencing activity.26,27,28,29 To test the assumption, we examined the effect of the GALA modification of PEG-NP (GALA-NP) on the immune response. The physical properties of the prepared GALA-NP were nearly the same as those for PEG-NP (Table 1). As shown in Figure 5, GALA modification successfully diminished serum IFN-α levels and IL-6 remained at a low level. The gene expression of Ifna in the spleen was also reduced by GALA modification.

Figure 5.

Modification of GALA suppressed interferon (IFN)-α production of PEGylation of NP (PEG-NP). Each sample (25 µg plasmid DNA (pDNA)/mouse) was intravenously injected at a normal pressure. At the indicated time after intervenous injection, serum (a) interleukin (IL-6) and (b) IFN-α were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The gene expression of Il6 and Ifna in the spleen was observed by semiquantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR. Closed squares, open circles, and closed triangles represent NP, PEG-NP, and GALA-NP, respectively. Even though serum IL-6 levels remained at the level in PEG-NP, GALA-NP caused negligible IFN-α production unlike PEG-NP. The gene expression of Ifna in the spleen was also decreased by GALA modification. HBG, HEPES-buffered glucose; NPs, nanoparticles; PEG-NP, PEGylation of NP.

Discussion

In this study, we applied a microarray analysis to understand the host response to pDNA encapsulated in lipid NPs. For the microarray analysis, we used a MEND, in which pDNA is condensed with PEI, followed by encapsulation with a lipid envelope consisting of 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP), dioleoylphosphatidyl ethanolamine (DOPE), and cholesterol. The systemic administration of the PEI/pDNA complex alone induced severe hepatotoxicity, but the innate immune response was negligible, unlike NPs (Supplementary Figure S1). These findings suggest that pDNA/PEI complex was successfully encapsulated by the lipid envelope of the MEND. These findings were also consistent with previous findings reported by Kawakami et al. in which a linear PEI polyplex showed negligible cytokine production and higher serum alanine transaminase levels after i.v. injection as compared with a N-[1-(2,3-dioleyloxy)propyl]-N,N,N-trimethylammonium chloride (DOTMA) based lipoplex.30,31 From this viewpoint, the MENDs can be thought of as a model of an NP.

The microarray analysis showed that, after the systemic administration of NPs, the upregulated genes in the spleen were mainly related to the immune system and the downregulated genes were associated with mitosis and differentiation, as shown in Table 2. These findings suggest that the characteristics between up- and downregulated genes are completely different, presumably because the innate upregulation of a gene related to immune system might turn out to downregulate genes related to the maintenance of cell function such as cytokinesis, mitosis, and cell differentiation. As we assumed, the variation in gene expression including Il6 and Ifng in clusters 1, 3, and 5 (55.8%) showed a tendency for improvement (Figures 1 and 2). Serum inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ were significantly decreased as the result of PEGylation (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Materials and Methods). Therefore, PEGylation appears to contribute to the prevention of inflammatory cytokine production. However, the variation of expression in cluster 2 (42.7%) was equivalent to the level of NP (Figure 1). Unexpectedly, the expression of type I IFN in the spleen was conversely aggravated by PEGylation (cluster 4; 1.5%)(Figures 1 and 2). As shown in Figure 3, the serum level of IFN-α in PEG-NP was equal to or greater than that for NP, in good agreement with the mRNA levels in the spleen. These results suggest that even though PEG is a well known biocompatible macromolecule, PEGylation is not an adequate solution to averting a host response to NPs.

The microarray analysis indicated that PEGylation altered the production of inflammatory cytokine such as Il6 (better) and type I IFN such as Ifna (unchanged or worse) in a different pattern. The question arises as to the cause of the production of inflammatory cytokines and type I IFN by NP and PEG-NP. PEG modification under these conditions did not alter the splenic accumulation of NP after systemic administration (Supplementary Figure S2). Therefore, the change in cytokine production might be caused after NPs that had arrived in the spleen. The innate immune response to a lipoplex is partially, but not entirely, dependent on the CpG motif in pDNA via TLR9, which induces the production of type I IFN and inflammatory cytokines.6 The plasmid DNA used in this study contains 425 CpG motifs.

Hartman et al. previously reported that a pathway analysis following a microarray of Ad revealed that the Myeloid differentiation primary response gene (88) (MyD88) in the TLR signaling pathway plays a major role in the immune response to Ad.14,15 To elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the response to NP and PEGylated NP, we then focused on the TLR signaling pathway using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes database. As a result of the pathway analysis, IL-6, IL-1β, and CD14 in cluster 3, and IFN-α and -β in cluster 4 correspond to the TLR signaling pathway (Figure 4). CD14 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored cell surface protein that is expressed by phagocytic cells.32 The recognition of lipopolysaccharide by cells is mediated by the lipopolysaccharide receptor complex, which consists of TLR4, MD2, and CD14.6 It was observed that CD14 expression by bone marrow granulocytes and odontoblasts was increased by treatment with an agonist for TLR4, such as lipopolysaccharide.33,34 It was reported that diC14-amidine, a cationic lipid, is assumed to be an agonist for TLR4 due to the association of the acyl chains of diC14-amidine with the hydrophobic pocket in MD2.35 Empty liposomes using the same lipid component in the envelope of NP showed neither inflammatory cytokine nor type I IFN production after systemic administration (data not shown). Therefore, it is very unlikely that the lipid components used in this study have the potential to function as a TLR4 agonist. However, since Cd14 expression was significantly altered, an NP that included pDNA would not be irrelevant to a TLR4 mediated immune response. Kedmi et al. recently reported that the immune activation of DOTAP based cationic lipid NPs containing siRNA might occur via TLR4, which provides support for our prediction.36

PEGylation decreased the expression of Cd14 as shown in Figure 2b, presumably because the cationic charge on the surface of the lipid envelope was masked by the PEG layer, which reduced the interaction of NP with biological milieu such as cellular membrane components. On the other hand, as describe above, PEGylation interrupts the intracellular trafficking of nanocarriers, especially in the case of endosomal escape.24,25 It is quite likely that the exposure time of pDNA to TLR9 in endosomes/lysosomes is prolonged due to the trapping of PEG-NP, which would lead to excess stimulation of TLR9, followed by an enhanced expression of IFN-α and -β. The time difference in the production of IL-6 and IFN-α provides support for our prediction. Inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α showed a peak response at 2 hour after i.v. administration, and the production dropped rapidly by 6 hour because the interaction of NPs with the cell surface had already occurred, which was followed by the immediate uptake of NPs via endocytosis. Although the initial production of IFN-α was slower than that of IL-6, the serum level of IFN-α increased over the 6 hour period after the i.v. injection of PEG-NP due to the prolonged interaction of CpG-DNA with TLR9 in endosomes.

Based on our hypothesis, we examined the effect of accelerating the endosomal escape of PEG-NP with GALA on the type I IFN production. We previously reported on the successful delivery of either an encapsulated aqueous phase marker, pDNA, or siRNA into the cytosol by introducing GALA on the lipid envelope.26,27,28,37 The acceleration in the endosomal escape of NP by GALA almost diminished IFN-α production, and IL-6 remained at low levels (Figure 5). The amount of GALA-NP in the spleen was comparable to that for NP and PEG-NP (Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary Materials and Methods). As an alternate to the use of GALA, PEG detached systems which have the ability to promote the endosomal escape of NPs, are considered to be another potential strategy for reducing type I IFN production in response to intracellular environments with a low pH in endosomes/lysosomes, reducing environment generated by small thiolytical molecules, e.g., glutathione, and enzymes such as cathepsin B.38,39,40,41

As anther type of DNA sensor, it was reported that DAI (ZBP1) has a role as a cytosolic dsDNA receptor in a CpG-independent manner.9 In this study, the expression of Zbp1 located in cluster 2 was increased tenfold by both NP and PEG-NP compared to the control. Although the amount of cytosolic pDNA escaping from endosomes would be increased by presence of GALA, no further immune response occurred. Therefore, the contribution of DAI in the immune response to NP would be minor, and GALA modification could reduce type I IFN production presumably because of the acceleration of endosomal escape. These results lead us to predict that the immune stimulation of NP mediated by TLR9 mainly results in the production of type I IFN in a CpG-dependent manner, whereas that mediated by TLR4 induces inflammatory cytokines in a CpG-independent manner. Although TLR 1/2 and 6 on the cell surface are also linked to inflammatory cytokine production, the involvement with TLR1/2 and 6 are presently unclear. Of course, further studies will be required to completely understand the mechanisms and pathways for the immune response.

In summary, a microarray-based analysis was performed, to explore the mechanism of host responses to systemically administrated NPs. As expected, PEGylation partially reduced the host response to NP. However, PEGylation also stimulated the response of type I IFN to NP. The pathway and mechanism analysis yielded insights into the causes of cytokine production and a strategy for the design of a carrier that can escape specific immune activation. This study provides the first rational strategy for reducing immunological stimulation based on the genome wide microarray analysis of systemically administrated nonviral lipid NPs.

Materials and Methods

Materials. Linear PEI (750 kDa) was purchased from SIGMA-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). DOTAP, DOPE, cholesterol, and distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phoshoethanolamine-N-[methoxy (polyethylene glycol)-2000] (PEG-DSPE) were obtained by Avanti Polar Lipid (Alabaster, AL). EndoFree Plasmid Giga Kit and RNeasy Mini Kit were purchased from QIAGEN (Hilden, Germany). RNase-free DNase I was purchased from TAKARA (Otsu, Japan). High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit was obtained from Agilent Technologies (Palo Alto, CA). Male imprinting control region mice (5–6 weeks old) were purchased from CLEA (Tokyo, Japan). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISA) assay kits of Quantikine Immunoassay mouse IL-6 was purchased from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN). ELISA assay kits of Verikine Mouse Interferon Alpha ELISA kit was purchased from PBL Biomedical Laboratories (New Brunswick, NJ).

Preparation of pDNA/PEI complex and NPs. pcDNA-3.1(+)-luc was prepared using an Endfree Plasmid Giga Kit, followed by purification with an Endotrap Blue to entirely eliminate traces of endotoxins. To formulate the pDNA/PEI complex, 200 µl of pDNA (0.1 mg/ml) was condensed with 100 µl of PEI (0.6 mmol/l) in 10 mmol/l HEPES buffer (pH 7.4), at a nitrogen/phosphate (N/P) ratio of 1:15. NPs were prepared by the lipid hydration method as reported previously.42 Briefly, a lipid film was prepared in a glass test tube by evaporating a chloroform solution of lipids, containing DOTAP, DOPE, and cholesterol (300 nmol total lipids in 3:4:3 molar ratio). For modifying of NP with PEG-DSPE or chol-GALA, the lipid film was prepared by evaporation with the indicated amounts of PEG-DSPE or chol-GALA. The lipid film then was hydrated with the 300 µl of pDNA/PEI complex solution for 10 minutes at room temperature, followed by sonication for ~1 minute in a bath-type sonicator (AU-25, AIWA, Tokyo, Japan). The average diameter and the ζ-potential of the condensed pDNA/PEI complex and NPs were determined using a Zetasizer Nano ZS ZEN3600 (MALVERN Instrument, Worchestershire, UK).

Animal experiments. Either the pDNA/PEI complex or NPs were administered to male imprinting control region mice via the tail vein, at a dose of 25 µg of pDNA. HBG treatment was used as a control. At the indicated times after injection, blood and spleen tissues were collected. Blood samples were stored for overnight at 4 °C, followed by centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 4 °C, 10 minutes) to obtain serum. Spleen samples were stored in RNA later solution at −20 °C to avoid RNA degradation. The experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Hokkaido University Animal Care Committee in accordance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.”

Determination of serum cytokine. IL-6 and IFN-α levels in serum were determined with ELISA kits according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR. A spleen sample was homogenized and total cellular RNA was purified using an RNeasy mini kit. To exclude DNA contamination, the RNA sample was treated with RNA free DNase I. Approximately 2.0 µg of RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed using a High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit by following manufacturer's instructions. PCRs were performed using the following primers: IL-6 (forward: 5′-TCCTCTGGTCTTCTGGAGTA-3′ and primer: 5′-TCCTTAGCCACTCCTTCTGT-3′); CD14 (forward: 5′-CTGATCTCAGCCCTCTGTCC-3′ and reverse: 5′-GCTTCAGCCCAGTGAAAGAC-3′); IFN-α (forward: 5′-GCTGCATGGAATACAACCCT-3′ and reverse: 5′-CTTCTGCTCTGACCACCTCC-3′); IFN-β (forward: 5′-GAGGAAAGATTGACGTGGGA-3′ and reverse: 5′-ACCACCACTCATTCTGAGGC-3′); β-actin (forward: 5′-ACATGGAGAAGATGTGGCAC-3′ and reverse: 5′-TCCATCACAATGCCTGTGGT-3′). β-actin was measured as an endogenous reference gene. The PCR thermocycling program was as follows: Denaturation at 94 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 60 °C for 30 seconds and extension at 70 °C for 30 seconds through 27–32 cycles. The PCR products were electrophoresed through a 2.0% agarose gel and then stained using ethidium bromide and visualized under UV light.

DNA mircoarray experiments. Spleen samples were homogenized and total cellular RNA was purified using an RNeasy mini kit, as described above. Total RNA extracted from four mice spleen (125 ng each) were pooled into one sample (total 500 ng) for normalizing individual differences. The integrity of the pooled total RNA samples was evaluated using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Foster City, CA). The pooled RNA was labeled with Cy-3 using the Low RNA Input Linear Amplification Kit PLUS, One-Color (Product No. 5188–5339), followed by purification using RNeasy mini kit to eliminate unlabeled Cy-3. Cy-3 labeled RNA sample was then hybridized to Agilent Whole Mouse Genome Microarray (Product No. G4122F) according to manufacturer's hybridization instruction. The microarray slides were analyzed using an Agilent Microarray scanner (Product No. G2565AA). Microarray expression data were obtained using the Agilent Feature Extraction software (Ver A.6.1.1).

Data analysis. Microarray data were analyzed using GeneSpring software version 7.3 (Agilent). Genes were regarded as upregulated when they had a ratio of ≥3 and as downregulated when they had a ratio of ≤0.34 in the administration of NP compared with HBG treatment. To understand the differential gene expression pattern, a hierarchical clustering analysis was performed using a Pearson Correlation and an average linkage clustering algorithm. The GO analysis was performed to assign biological meaning to the subset of gene clusters. Over-representation of genes with altered expression in the NP treatment compared with the HBG treatment within specific GO categories was determined using Fisher's exact probability test. Pathway analysis of TLR signaling pathway was performed by using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway map.

Statistical analysis. Comparisons between multiple treatments were made using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni test. Pair-wise comparisons between treatments were made using a Student's t-test. A P-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Serum levels of (a) IL-6 and (b) IFN-γ (c) TNF-α and (d) ALT. Each sample (25 μg pDNA/mouse) was intravenously injected at a normal pressure. At 2, 6 or 24 hr after i.v. injection, cytokines or ALT value in serum were evaluated. Closed squares, open circles and gray diamonds represent NP, PEG-NP and PEI/pDNA complex, respectively. NP induced inflammatory cytokine productions, on the other hand, PEGylation inhibits that. PEI/pDNA complex alone presented no cytokine in serum. However, PEI/pDNA induced severe hepatotoxicity. Figure S2. Accumulation of NPs in the spleen. NPs were labeled with [3H]CHE. Each sample (25 μg pDNA/mouse) was intravenously injected at a normal pressure. At 2 hr after i.v. injection, spleen was collected and the radioactivity in the spleen was measured. Tumor accumulation is represented as the % injected dose (ID) per tissue. Comparisons between multiple treatments were made using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). N.D.: Not significant differences. The modification of PEG and GALA didn't alter the accumulation of NPs in spleen. Therefore, the different pattern of cytokine and interferon production presumably resulted from the alternation of intracellular fate of NP by modification of PEG and GALA. Materials and Methods.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), and Grant for Industrial Technology Research from New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO), and by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). We thank M. S. Feather for his helpful advice in writing the English manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Serum levels of (a) IL-6 and (b) IFN-γ (c) TNF-α and (d) ALT. Each sample (25 μg pDNA/mouse) was intravenously injected at a normal pressure. At 2, 6 or 24 hr after i.v. injection, cytokines or ALT value in serum were evaluated. Closed squares, open circles and gray diamonds represent NP, PEG-NP and PEI/pDNA complex, respectively. NP induced inflammatory cytokine productions, on the other hand, PEGylation inhibits that. PEI/pDNA complex alone presented no cytokine in serum. However, PEI/pDNA induced severe hepatotoxicity.

Accumulation of NPs in the spleen. NPs were labeled with [3H]CHE. Each sample (25 μg pDNA/mouse) was intravenously injected at a normal pressure. At 2 hr after i.v. injection, spleen was collected and the radioactivity in the spleen was measured. Tumor accumulation is represented as the % injected dose (ID) per tissue. Comparisons between multiple treatments were made using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). N.D.: Not significant differences. The modification of PEG and GALA didn't alter the accumulation of NPs in spleen. Therefore, the different pattern of cytokine and interferon production presumably resulted from the alternation of intracellular fate of NP by modification of PEG and GALA.

REFERENCES

- Deakin CT, Alexander IE., and, Kerridge I. Accepting risk in clinical research: is the gene therapy field becoming too risk-averse. Mol Ther. 2009;17:1842–1848. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SD., and, Huang L. Gene therapy progress and prospects: non-viral gene therapy by systemic delivery. Gene Ther. 2006;13:1313–1319. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tros de Ilarduya C, Sun Y., and, Düzgünes N. Gene delivery by lipoplexes and polyplexes. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2010;40:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada K, Christie RJ., and, Kataoka K. Polymeric micelles from poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(amino acid) block copolymer for drug and gene delivery. J R Soc Interface. 2009;6 Suppl 3:S325–S339. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0547.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore M, Li S., and, Huang L. LPD lipopolyplex initiates a potent cytokine response and inhibits tumor growth. Gene Ther. 1999;6:1867–1875. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T., and, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Hemmi H, Akira S, Cheng SH, Scheule RK., and, Yew NS. Contribution of toll-like receptor -9 signaling to the acute inflammatory response to nonviral vectors. Mol Ther. 2004;9:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai H, Sakurai F, Kawabata K, Sasaki T, Koizumi N, Huang H.et al. (2007Comparison of gene expression efficiency and innate immune response induced by Ad vector and lipoplex J Control Release 117430–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda K, Ogawa Y, Yamane I, Nishikawa M., and, Takakura Y. Macrophage activation by a DNA/cationic liposome complex requires endosomal acidification and TLR9-dependent and -independent pathways. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:71–79. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0204089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka A, Wang Z, Choi MK, Yanai H, Negishi H, Ban T.et al. (2007DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response Nature 448501–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda S, Yoshida H, Nishikawa M., and, Takakura Y. Comparison of the type of liposome involving cytokine production induced by non-CpG Lipoplex in macrophages. Mol Pharm. 2010;7:533–542. doi: 10.1021/mp900247d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayakhmetov DM, Di Paolo NC., and, Mossman KL. Recognition of virus infection and innate host responses to viral gene therapy vectors. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1422–1429. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey AP, Fawcett P, Nakai H, McCaffrey RL, Ehrhardt A, Pham TT.et al. (2008The host response to adenovirus, helper-dependent adenovirus, and adeno-associated virus in mouse liver Mol Ther 16931–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman ZC, Kiang A, Everett RS, Serra D, Yang XY, Clay TM.et al. (2007Adenovirus infection triggers a rapid, MyD88-regulated transcriptome response critical to acute-phase and adaptive immune responses in vivo J Virol 811796–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman ZC, Black EP., and, Amalfitano A. Adenoviral infection induces a multi-faceted innate cellular immune response that is mediated by the toll-like receptor pathway in A549 cells. Virology. 2007;358:357–372. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omidi Y, Hollins AJ, Drayton RM., and, Akhtar S. Polypropylenimine dendrimer-induced gene expression changes: the effect of complexation with DNA, dendrimer generation and cell type. J Drug Target. 2005;13:431–443. doi: 10.1080/10611860500418881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omidi Y, Hollins AJ, Benboubetra M, Drayton R, Benter IF., and, Akhtar S. Toxicogenomics of non-viral vectors for gene therapy: a microarray study of lipofectin- and oligofectamine-induced gene expression changes in human epithelial cells. J Drug Target. 2003;11:311–323. doi: 10.1080/10611860310001636908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagami T, Hirose K, Barichello JM, Ishida T., and, Kiwada H. Global gene expression profiling in cultured cells is strongly influenced by treatment with siRNA-cationic liposome complexes. Pharm Res. 2008;25:2497–2504. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9663-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyerle A, Irmler M, Beckers J, Kissel T., and, Stoeger T. Toxicity pathway focused gene expression profiling of PEI-based polymers for pulmonary applications. Mol Pharm. 2010;7:727–737. doi: 10.1021/mp900278x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogure K, Akita H, Yamada Y., and, Harashima H. Multifunctional envelope-type nano device (MEND) as a non-viral gene delivery system. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:559–571. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesta MF. Normal structure, function, and histology of the spleen. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34:455–465. doi: 10.1080/01926230600867743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexis F, Pridgen E, Molnar LK., and, Farokhzad OC. Factors affecting the clearance and biodistribution of polymeric nanoparticles. Mol Pharm. 2008;5:505–515. doi: 10.1021/mp800051m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafez IM., and, Cullis PR. Roles of lipid polymorphism in intracellular delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;47:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00103-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S, Webster P., and, Davis ME. PEGylation significantly affects cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking of non-viral gene delivery particles. Eur J Cell Biol. 2004;83:97–111. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remaut K, Lucas B, Braeckmans K, Demeester J., and, De Smedt SC. Pegylation of liposomes favours the endosomal degradation of the delivered phosphodiester oligonucleotides. J Control Release. 2007;117:256–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki K, Kogure K, Chaki S, Nakamura Y, Moriguchi R, Hamada H.et al. (2008An artificial virus-like nano carrier system: enhanced endosomal escape of nanoparticles via synergistic action of pH-sensitive fusogenic peptide derivatives Anal Bioanal Chem 3912717–2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai Y, Hatakeyama H, Akita H, Oishi M, Nagasaki Y, Futaki S.et al. (2009Efficient short interference RNA delivery to tumor cells using a combination of octaarginine, GALA and tumor-specific, cleavable polyethylene glycol system Biol Pharm Bull 32928–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama H, Ito E, Akita H, Oishi M, Nagasaki Y, Futaki S.et al. (2009A pH-sensitive fusogenic peptide facilitates endosomal escape and greatly enhances the gene silencing of siRNA-containing nanoparticles in vitro and in vivo J Control Release 139127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Nicol F., and, Szoka FC., Jr GALA: a designed synthetic pH-responsive amphipathic peptide with applications in drug and gene delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:967–985. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami S, Ito Y, Charoensit P, Yamashita F., and, Hashida M. Evaluation of proinflammatory cytokine production induced by linear and branched polyethylenimine/plasmid DNA complexes in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:1382–1390. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.100669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Higuchi Y, Kawakami S, Yamashita F., and, Hashida M. Immunostimulatory characteristics induced by linear polyethyleneimine-plasmid DNA complexes in cultured macrophages. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:137–145. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg MA, Tchaptchet S, Keck S, Fejer G, Huber M, Schütze N.et al. (2008Lipopolysaccharide sensing an important factor in the innate immune response to Gram-negative bacterial infections: benefits and hazards of LPS hypersensitivity Immunobiology 213193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botero TM, Shelburne CE, Holland GR, Hanks CT., and, Nör JE. TLR4 mediates LPS-induced VEGF expression in odontoblasts. J Endod. 2006;32:951–955. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedron T, Girard R, Inoue K, Charon D., and, Chaby R. Lipopolysaccharide and the glycoside ring of staurosporine induce CD14 expression on bone marrow granulocytes by different mechanisms. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52:692–700. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Legat A, Adam E, Steuve J, Gatot JS, Vandenbranden M.et al. (2008DiC14-amidine cationic liposomes stimulate myeloid dendritic cells through Toll-like receptor 4 Eur J Immunol 381351–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedmi R, Ben-Arie N., and, Peer D. The systemic toxicity of positively charged lipid nanoparticles and the role of Toll-like receptor 4 in immune activation. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6867–6875. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakudo T, Chaki S, Futaki S, Nakase I, Akaji K, Kawakami T.et al. (2004Transferrin-modified liposomes equipped with a pH-sensitive fusogenic peptide: an artificial viral-like delivery system Biochemistry 435618–5628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Huang Z, MacKay JA, Grube S., and, Szoka FC., Jr Low-pH-sensitive poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-stabilized plasmid nanolipoparticles: effects of PEG chain length, lipid composition and assembly conditions on gene delivery. J Gene Med. 2005;7:67–79. doi: 10.1002/jgm.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J, Shum P., and, Thompson DH. Acid-triggered release via dePEGylation of DOPE liposomes containing acid-labile vinyl ether PEG-lipids. J Control Release. 2003;91:187–200. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalipsky S, Qazen M, Walker JA., 2nd, , Mullah N, Quinn YP., and, Huang SK. New detachable poly(ethylene glycol) conjugates: cysteine-cleavable lipopolymers regenerating natural phospholipid, diacyl phosphatidylethanolamine. Bioconjug Chem. 1999;10:703–707. doi: 10.1021/bc990031n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JX, Zalipsky S, Mullah N, Pechar M., and, Allen TM. Pharmaco attributes of dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine/cholesterylhemisuccinate liposomes containing different types of cleavable lipopolymers. Pharmacol Res. 2004;49:185–198. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama H, Akita H, Kogure K, Oishi M, Nagasaki Y, Kihira Y.et al. (2007Development of a novel systemic gene delivery system for cancer therapy with a tumor-specific cleavable PEG-lipid Gene Ther 1468–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Serum levels of (a) IL-6 and (b) IFN-γ (c) TNF-α and (d) ALT. Each sample (25 μg pDNA/mouse) was intravenously injected at a normal pressure. At 2, 6 or 24 hr after i.v. injection, cytokines or ALT value in serum were evaluated. Closed squares, open circles and gray diamonds represent NP, PEG-NP and PEI/pDNA complex, respectively. NP induced inflammatory cytokine productions, on the other hand, PEGylation inhibits that. PEI/pDNA complex alone presented no cytokine in serum. However, PEI/pDNA induced severe hepatotoxicity.

Accumulation of NPs in the spleen. NPs were labeled with [3H]CHE. Each sample (25 μg pDNA/mouse) was intravenously injected at a normal pressure. At 2 hr after i.v. injection, spleen was collected and the radioactivity in the spleen was measured. Tumor accumulation is represented as the % injected dose (ID) per tissue. Comparisons between multiple treatments were made using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). N.D.: Not significant differences. The modification of PEG and GALA didn't alter the accumulation of NPs in spleen. Therefore, the different pattern of cytokine and interferon production presumably resulted from the alternation of intracellular fate of NP by modification of PEG and GALA.