Abstract

Estrogens are major risk factors for the development of breast cancer; they can be metabolized to catechols, which are further oxidized to DNA-reactive quinones and semiquinones (SQs). These metabolites are mutagenic and may contribute to the carcinogenic activity of estrogens. Redox cycling of the SQs and subsequent generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is also an important mechanism leading to DNA damage. The SQs of exogenous estrogens have been shown to redox cycle, however, redox cycling and the generation of ROS by endogenous estrogens has never been characterized. In the present studies, we determined whether the catechol metabolites of endogenous estrogens, including 2-hydroxyestradiol, 4-hydroxyestradiol, 4-hydroxyestrone and 2-hydroxyestriol, can redox cycle in breast epithelial cells. These catechol estrogens, but not estradiol, estrone, estriol or 2-methoxyestradiol, were found to redox cycle and generate hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl radicals in lysates of three different breast epithelial cell lines: MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-10A. The generation of ROS required reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate as a reducing equivalent and was inhibited by diphenyleneiodonium, a flavoenzyme inhibitor, indicating that redox cycling is mediated by flavin-containing oxidoreductases. Using extracellular microsensors, catechol estrogen metabolites stimulated the release of H2O2 by adherent cells, indicating that redox cycling occurs in viable intact cells. Taken together, these data demonstrate that catechol metabolites of endogenous estrogens undergo redox cycling in breast epithelial cells, resulting in ROS production. Depending on the localized concentrations of catechol estrogens and enzymes that mediate redox cycling, this may be an important mechanism contributing to the development of breast cancer.

Introduction

Human and animal studies suggest that exposure to hormone replacement therapies and other estrogens is a major risk factor for the development of idiopathic postmenopausal mammary cancer (1–8). Meta-analysis of >50 independent studies demonstrated a direct correlation between human estrogen exposure and an increased incidence of breast cancer (1,9). Similarly, a 24% increase in breast cancer incidence was observed in a randomized control trial of the exogenous equine estrogens in Premarin (10). Samples collected from the trial participants suggest an increase in measurable DNA damage in both the malignant and non-malignant breast tissues from the experimental arms of the study when compared with those from the control arm (11). Additionally, oxidative stress and DNA damage are elevated in tissue samples of breast cancer patients versus women who had mammoplasties (12–14). Animal studies have also confirmed a dose-dependent link between oxidative and DNA damage and catechol estrogen exposure (13,15–20).

The carcinogenic potential of equine estrogens is widely attributed to the metabolism of equilin (3-hydroxyestra-1,3,5,7-tetraen-17-one), to redox active catechol metabolites, via cytochrome P450 isozymes CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 (21–24). The endogenous estrogen, estradiol (E2), is also a substrate for CYP1A1 and CYP1B1, generating 2-hydroxyestradiol (2OHE2) and 4-hydroxyestradiol (4OHE2) (Figure 1) (25). These catechol metabolites have the capacity to undergo one-electron oxidation by reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-cytochrome P450 reductase (POR) to form reactive SQ intermediates (26), which can modify DNA and are potential mutagens (18,21,27). Alternatively, the SQs can pass their unpaired electron to molecular oxygen, forming superoxide anion and restoring the catechol in a process referred to as redox cycling. Superoxide anion can be metabolized to other reactive oxygen species (ROS), including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and, in the presence of transition metals, highly mutagenic hydroxyl radicals (26,28). Excessive ROS cause lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation and DNA damage, which have been observed in both animals and humans exposed to estrogens (14,22,24,26,29,30).

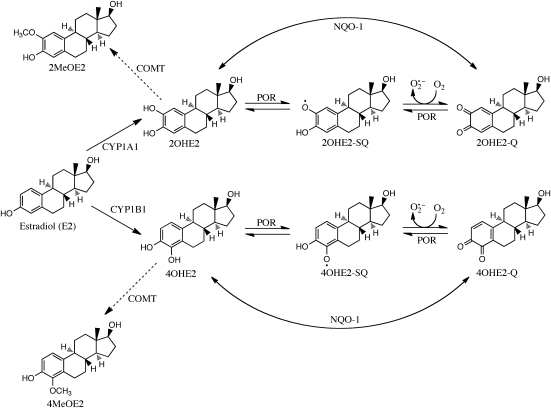

Fig. 1.

Metabolism of estradiol to catechol estrogens by cytochrome P450s 1A1 and 1B1. Estradiol is metabolized to a catechol by CYP1A1 and CYP1B1. The one-electron oxidation of the estradiol catechol metabolites to SQ and quinones (Q) by NADPH-POR and subsequent redox-cycling results in the production of cytotoxic ROS. In contrast, the two-electron oxidation–reduction of these catechol metabolites by enzymes such as NADPH-quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO-1) is thought to be cytoprotective. Since the catechol metabolites, but not the SQ and Q oxidation products, can be methylated by catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) and excreted, NQO-1 is thought to catalyze a net reaction toward this detoxification pathway.

The link between endogenous estrogens and breast cancer suggests that they may also be metabolized to reactive intermediates that contribute to the carcinogenic process (31). However, few studies have characterized redox cycling of endogenous estrogens or their metabolites. Earlier work has proposed that the SQ formed from the endogenous catechol estrogen, 2OHE2 may form a quinone in the presence of NADPH or cumene peroxidase and rat liver microsomes; however, these studies failed to demonstrate any signs of redox cycling (including ROS generation, reducing agent depletion and an increase in oxygen consumption) by this endogenous catechol (26). Furthermore, the stimulation of ROS generation that typifies redox cycling has never been characterized using an endogenous estrogen. In the present studies, we demonstrate that four catechol metabolites of estrone (E1), E2 and estriol (E3) are highly redox active and generate ROS. These data support the idea that redox cycling by endogenous catechol estrogens may contribute to breast tumorigenesis.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Amplex red (10-acetyl-3, 7-dihydroxyphenoxazine) was obtained from Invitrogen (Eugene, OR). The estrogens, NADPH, terephthalate and all other chemicals were from Sigma–Aldrich (St Louis, MO).

Cell culture and preparation of cell lysates

MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-10A breast epithelial cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 are transformed cells and were maintained in Dubecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Mediatech, Manassas, VA), 100 U/ml penicillin/100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY). MCF-10A is a non-tumorigenic cell line and was grown in Mammary Epithelial Basal Medium supplemented with Lonza’s BulletKit™ (Walkersville, MD), containing insulin, hydrocortisone, recombinant human epidermal growth factor, bovine pituitary extract, gentamycin and amphotericin B. Cells which overexpress cytochrome P450 reductase (CHO-OR) and wild-type control cells (CHO-WT cells) were obtained and maintained as described previously by our laboratory (32–34). All cell lines were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. To prepare lysates, cells were trypsinized, washed and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (106 cells/ml). Cells were then disrupted on ice using a probe sonicator (Artek Systems, Farmingdale, NY). Protein concentrations were quantified using the DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Analysis of ROS production

All assays for ROS were performed in 96-well black microtiter plates at 37°C. H2O2 production in redox-cycling enzyme assays was measured using the Amplex red/horseradish peroxidase method as described previously (35,36). Reactions in 100 μl volumes contained 70 mM NaCl in potassium phosphate buffer (30 mM, pH 7.8) supplemented with 100 μM NADPH, 100 μM Amplex red, 1 U/ml horseradish peroxidase, 50 μg/ml cell lysate protein and various concentrations of estrogens or estrogen metabolites. The fluorescence of the reaction product, resorufin (excitation 540 nm/emission 595 nm), was recorded using a SpectraMax M5 fluorescent microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The terephthalate assay was used to measure hydroxyl radical generation (37). In this assay, hydroxyl radicals are scavenged by the non-fluorescent substrate terephthalate, producing the fluorescent product 2-hydroxyterephthalate (2-OH-TPT, excitation 315 nm/emission 425 nm). Fluorescence was measured using a spectrofluorometric microplate reader. Reactions were analyzed in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline containing 100 μM NADPH, 50 μg/ml cell lysate protein, 100 μM FeCl3, 110 μM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1 mM terephthalate and appropriate concentrations of either estrogens or estrogen metabolites. Because estrogens are sparingly soluble in buffer systems and most organic solvents are hydroxyl radical scavengers, stock solutions of estrogens (100×) dissolved in isopropanol were added to the wells of the microplates and evaporated overnight prior to the addition of other assay reagents.

H2O2 release was quantified using platinum amperometric microsensors as described previously with minor alterations (38). Briefly, the culture medium from 60 to 80% confluent monolayers of cells was replaced with Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer (4 mM glucose, 140 mM NaCl, 30 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, 4.6. mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.15 mM Na2HPO4, 0.4 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM CaCl2 and 0.05% bovine serum albumin, pH 7.4, osmolarity 284 mosM) just prior to analysis (39). After measuring basal H2O2, increasing volumes of a stock solution of estrogens or estrogen metabolites (10 mM in isopropanol) were added to the buffer. Each addition was directly followed by electrochemical H2O2 quantification using the microsensors. All experiments were performed at room temperature. Each microsensor was hand-manufactured before each experiment and therefore displayed unique noise characteristics that were evident in the tracings. The microsensors used in our experiments had a linear response in the range of 0.3–30 μM H2O2 (Figure 2).

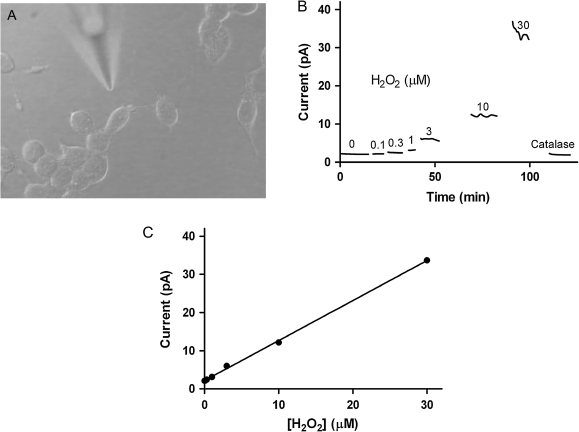

Fig. 2.

H2O2 release by cells in culture measured electrochemically using a microsensor. Panel (A) shows a typical microsensor used to quantify H2O2 released by cells. When placed near cells, these electrodes are able to measure H2O2 with high temporal and spatial resolution. The microsensors produce additional current when placed in a solution containing increasing concentrations of H2O2 (Panels B and C). The addition of catalase to this solution consumes H2O2, restoring basal current levels.

Results

In initial studies, we characterized redox cycling by estrogens and estrogen metabolites in lysates of MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-10A cells by quantifying H2O2 and hydroxyl radical generation. MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 are estrogen receptor (ER)-positive and ER-negative tumorigenic cell lines, respectively, whereas MCF-10A is an ER-negative non-tumorigenic transformed cell line. We found that the catechol estrogen metabolites 2OHE2 and 4OHE2, but not E2 or the methoxy-estrogen metabolite 2-methoxyestradiol (2MeOE2), readily generated H2O2 in lysates from each cell type (Figure 3). Similar redox cycling was observed with 4-hydroxyestrone (4OHE1) and 2-hydroxyestriol (2OHE3), but not E1 or E3 (data not shown). H2O2 formation by all redox active catechol estrogen metabolites was linear with respect to time and concentration (Figure 3A) and was inhibited by the flavin inhibitor diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) (supplementary Figure 1 is available at Carcinogenesis Online). The antioxidant enzyme catalase also prevented the accumulation of H2O2 in enzyme assays (supplementary Figure 1 is available at Carcinogenesis Online). It has been previously suggested that POR mediates catechol estrogen redox cycling (26,28). By comparing CHO cells overexpressing cytochrome P450 reductase (CHO-OR cells) with wild-type controls (CHO-WT cells), we found that the rate of 2OHE2-stimulated H2O2 production is dependent on POR expression (supplementary Figure 2 is available at Carcinogenesis Online).

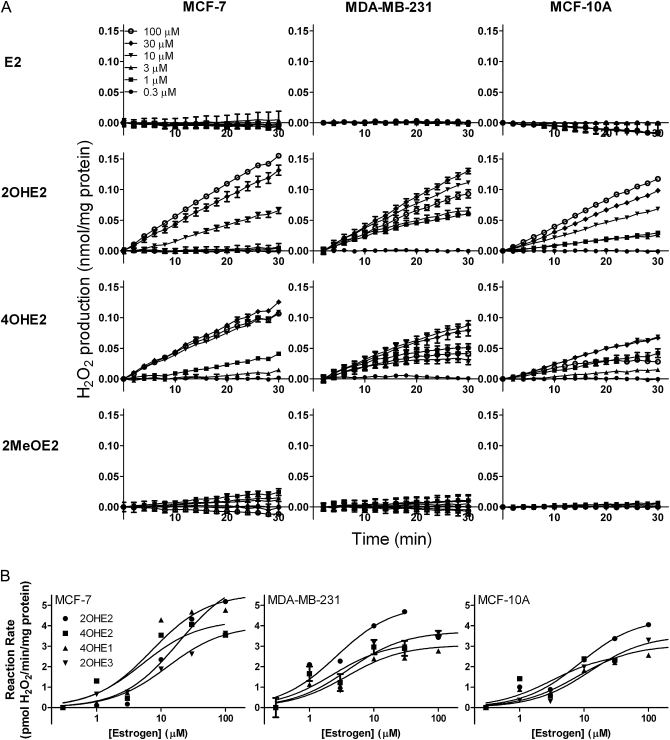

Fig. 3.

H2O2 production by redox cycling of catechol metabolites of estrogen by breast epithelial cells. Panel (A): Effects of increasing concentration of estradiol or its catechol metabolites on the production of H2O2. Assay mixtures contained 50 μg/ml lysate protein from MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 or MCF-10A cells and increasing concentrations of either E2, 2OHE2, 4OHE2 or 2MeOE2. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). Panel (B): Effects of increasing concentrations of estrogen or its catechol metabolites on the rate of H2O2 production by breast epithelial cells. Assay mixtures contained 50 μg/ml cell lysate protein from the different cell types and increasing concentrations of either 2OHE2, 4OHE2, 4OHE1 or 2OHE3. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3).

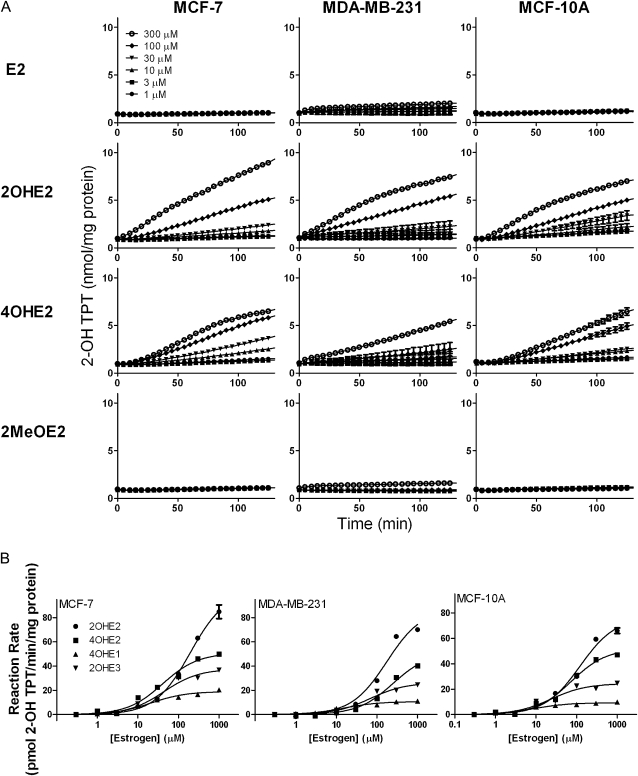

The rates of H2O2 generation in the three breast epithelial cell lines by 2OHE2, 4OHE2, 4OHE1 and 2OHE3 were further analyzed using Michaelis–Menten kinetics; the apparent KM’s ranged from 2.29 to 18.9 μM and Vmax’s from 2.67 to 6.42 pmol H2O2/min/mg protein (Figure 3B and Table I). The redox active catechol estradiol metabolites also stimulated hydroxyl radical formation in cell lysates; this reaction was both time and concentration dependent (Figure 4A). Accumulation of hydroxyl radicals was prevented by DPI and catalase as well as the hydroxyl radical scavenger dimethyl sulfoxide (supplementary Figure 3 is available at Carcinogenesis Online). The apparent KM’s and Vmax’s for catechol estrogen redox cycling ranged from 8.85 to 250 μM and 9.29 to 102 pmol 2-OH-TPT/min/mg protein Figure 4B and Table I). The kinetic constants for hydroxyl radical formation were lowest with 4OHE1 and highest with 2-OHE2. E1, E2, E3 and 2MeOE2 had no effect on the generation of hydroxyl radicals by the cell lysates (Figure 4B and data not shown).

Table I.

Kinetic constants for catechol estrogen redox-cycling in breast cell lysates

| Catechol estrogen |

|||||

| Cell typea | 2OHE2 | 4OHE2 | 4OHE1 | 2OHE3 | |

| H2O2 formation | |||||

| MCF-7 | Vmax | 6.42 ± 0.76 | 4.28 ± 0.79 | 5.57 ± 0.39 | 4.01 ± 0.22 |

| KM | 18.9 ± 6.6 | 5.17 ± 3.74 | 7.14 ± 2.62 | 12.7 ± 3.4 | |

| MCF-10A | Vmax | 4.37 ± 0.36 | 2.67 ± 0.83 | 3.05 ± 0.20 | 3.53 ± 0.22 |

| KM | 8.74 ± 2.58 | 3.20 ± 3.43 | 7.93 ± 2.73 | 12.2 ± 3.6 | |

| MDA-MB-231 | Vmax | 5.02 ± 0.65 | 3.22 ± 0.66 | 3.05 ± 0.18 | 3.72 ± 0.31 |

| KM | 2.61 ± 1.22 | 2.29 ± 1.73 | 3.79 ± 1.21 | 4.03 ± 1.86 | |

| Hydroxyl radical formation | |||||

| MCF-7 | Vmax | 102 ± 2 | 50.9 ± 2.6 | 19.1 ± 1.0 | 37.7 ± 2.3 |

| KM | 196 ± 11 | 41.0 ± 8.7 | 20.9 ± 4.8 | 43.7 ± 10.9 | |

| MCF-10A | Vmax | 76.4 ± 4.1 | 51.9 ± 2.3 | 9.29 ± 0.44 | 24.4 ± 1.9 |

| KM | 122 ± 21 | 73.1 ± 12.1 | 8.85 ± 2.11 | 23.6 ± 8.4 | |

| MDA-MB-231 | Vmax | 87.4 ± 8.4 | 51.4 ± 3.4 | 10.7 ± 0.5 | 26.4 ± 2.1 |

| KM | 175 ± 50 | 250 ± 45 | 15.2 ± 3.0 | 67.7 ± 20.0 | |

Cell lysates were assayed for catechol estrogen redox cycling activity using either the Amplex red assay for H2O2 or the terephthalate assay for hydroxyl radicals. Data were analyzed using the Michaelis–Menten kinetic algorithm in GraphPad Prism v.5.04. Each point represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Fig. 4.

Hydroxyl radical production by redox cycling of catechol metabolites of estrogen by breast epithelial cells. Panel (A): Effects of increasing concentration of estradiol or its catechol metabolites on hydroxyl radical production. Assay mixtures contained 50 μg/ml lysate protein from the MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 or MCF-10A cells and increasing concentrations of either E2, 2OHE2, 4OHE2 or 2MeOE2. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). Panel (B): Effects of increasing concentrations of estrogen or its catechol metabolites on the rate of hydroxyl radical formation by breast epithelial cells. Assay mixtures contained cell lysate protein from each of the breast cell lines and increasing concentrations of either 2OHE2, 4OHE2, 4OHE1 or 2OHE3. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3).

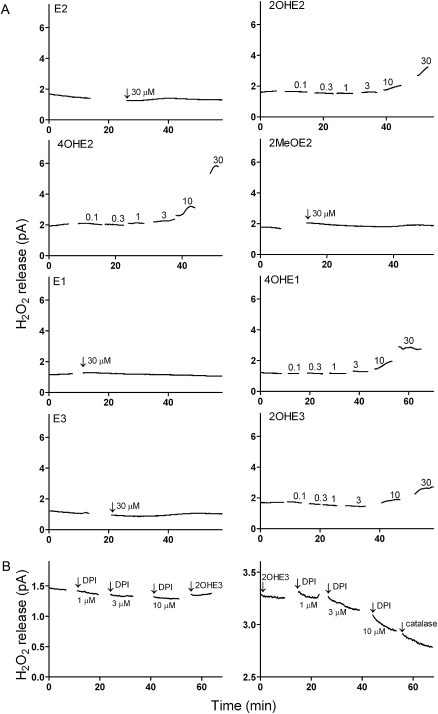

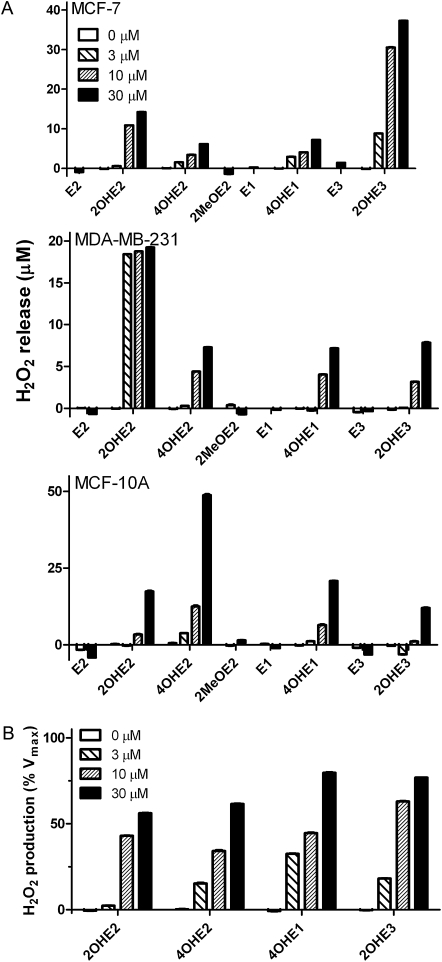

H2O2 is membrane permeable and can readily diffuse from cells into their culture medium. We next determined whether catechol estrogen redox cycling-stimulated H2O2 release by intact cells. For these experiments, extracellular H2O2 production was measured using an amperometric platinum microsensor (38). Each of the four redox active catechol estrogens was found to stimulate H2O2 release by MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-10A cells (Figure 5). H2O2 release was not observed with E1, E2, E3 or 2MeOE2 (Figures 5A and 6A). Catechol estrogen metabolite-stimulated cellular H2O2 release was evident at concentrations up to 30 μM, the highest concentrations tested (Figures 5A and 6A). H2O2 release by the cells was also inhibited by DPI. Pretreatment of MDA-MB-231 cells with DPI (10–100 μM) prevented 2OHE3-stimulated H2O2 release. H2O2 release was also reduced by DPI after catechol estrogen treatment and inhibited by catalase (Figure 5B). Michaelis–Menten kinetics was used to compare H2O2 release by the cells. We found that the catechol estrogen metabolites were generally similar in their ability to stimulate H2O2 production by the breast epithelial cells (Figure 6B).

Fig. 5.

Redox cycling by of catechol metabolites of endogenous estrogens stimulates H2O2 release by breast epithelial cells. Panel (A): Cells were treated with the parent estrogens (E2, E1 or E3), methoxyestrogen (2MeOE2) or catechol estrogens (2OHE2, 4OHE2, 4OHE1, 2OHE3) and then analyzed for extracellular H2O2 release using microsensors. Note that H2O2 was only released by cells treated with the catechol estrogens. Panel (B): Effects of DPI and catalase on catechol estrogen metabolite stimulated of H2O2 release by MDA-MB-231 cells. Adherent cells were treated with increasing concentrations of the flavoenzyme inhibitor DPI before (left panel) or after (right panel) the addition of 10 μM 2OHE3. Note that DPI effectively prevented 2OHE3-stimulated H2O2 production (left panel), whereas DPI decreased 2OHE3-stimulated H2O2 generation (right panel). Catalase (1000 U) further increased the rate of H2O2 amelioration. Each panel is one of three representative experiments.

Fig. 6.

Effects of catechol estrogens on H2O2 release by breast epithelial cells. Panel (A): H2O2 release by intact breast epithelial cells. A microsensor was used to measure H2O2 released by adherent MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 or MCF-10A cells treated with estrogens or their metabolites. The data shown represent temporal averages of representative experiments [mean ± SEM (n ≥ 182)]. Panel (B): H2O2 release by MCF-7 cells. Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of estrogens. Data are presented as a percentage of the calculated Vmax.

Discussion

It is generally accepted that exposure to estrogens is an important risk factor for the development of mammary cancer (40,41). The carcinogenic process is thought to involve many factors including the promotion of random mutations due to ER-mediated changes in transcription (42), stimulation of non-ER-mediated signal transduction (43–45) and the generation of estrogen metabolites. Estrogen metabolism to catechols and subsequent methylation by catechol-O-methyltransferase is generally considered to be a detoxifying pathway because these metabolites can be readily excreted. However, increases in the metabolism of estrogens to catechols or decreases in the rate of methylation can result in the formation of reactive estrogen-SQs, which alkylate DNA (15,18–20,46,47). Recent evidence suggests that redox cycling by exogenous catechol estrogen SQs may also contribute to their carcinogenic activity (15,21). However, no studies have ever characterized ROS generation resulting from endogenous catechol estrogen-stimulated redox cycling. In the present studies, we characterized this activity in three different breast epithelial cell lines with varying tumorigenic potential. In each of the cell types, the endogenous catechol estrogens were found to redox cycle and generate ROS, including H2O2 and hydroxyl radicals; redox cycling was not observed with the parent estrogens or the methoxy metabolite. These findings are consistent with reports that the catechol structure is an important structural requirement for redox cycling activity (48). While all estrogens tested display the high degree of conjugation needed to stabilize the SQ radical intermediate, only the catechol estrogens contain unprotected oxygen atoms on adjacent carbons. Each of these oxygen atoms exists in either a carbonyl (oxidized) or as a hydroxyl (reduced) form. In a partially oxidized or reduced SQ radical, the oxidized carbonyl oxygen atom contributes to the overall stability of the molecule by additional conjugation of its pi-bonding electrons. This electrophilic conjugation provides enough of a dipole moment along the remaining hydroxyl bond for deprotonation to occur, forming the radical. The same conjugation also stabilizes the unpaired electron, thus the radical formed can function as a reactive metabolite rather than as a transient intermediate (22,48).

MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-10A cells represent human mammary epithelial cells at various stages of breast cancer development. Although MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells both originate from the plural effusion of human breast adenocarcinomas, they have distinct properties. Thus, whereas MCF-7 cells retain some characteristics of differentiated mammary epithelium, such as the expression of cytoplasmic ER alpha (ERα) (49), and are commonly used to model low-grade breast epithelial adenocarcinomas (52–54), MDA-MB-231 cells are poorly differentiated, do not express ERα and are insensitive to anti-estrogens (49). Originating from the fibrocystic lesion of a premenopausal woman, MCF-10A cells express a number of mammary epithelial markers (49) and are distinct in that they are transformed, but not tumorigenic. We found that the capacity of each of these breast cell lines to mediate redox cycling, the amount of ROS generated, the rate of ROS production, the reversibility of the redox cycling reaction and the maximal reaction rates, were generally comparable for each catechol estrogen. Thus, any measurable differences between the antioxidant potentials of the three cell lines are rendered insignificant by the magnitude of catechol estrogen-stimulated ROS generation. These data also suggest that redox cycling is independent of ERα expression, state of differentiation and tumorigenic potential. It may be that the ability to mediate catechol estrogen redox cycling and ROS production is a fundamental property of the breast epithelial cells; moreover, redox cycling by catechol metabolites of endogenous estrogens may precede the carcinogenic process.

The present studies demonstrate that breast tumor cell lysates have the capacity to generate ROS during catechol estrogen redox cycling, including both H2O2 and hydroxyl radicals. It is generally thought that redox cycling generates ROS via the univalent reduction of oxygen resulting in the formation of superoxide anion (55). In this reaction, one molecule of oxygen oxidizes two molecules of NADPH generating two molecules of superoxide anion (56). The further reduction of superoxide anion produces H2O2 and hydroxyl radicals in the presence of transition metals. The Vmax’s and apparent KM’s for the formation of H2O2 ranged from 2.67 to 6.42 pmol H2O2/min/mg protein and 2.29 to 18.9 μM, respectively. Of interest were our findings that the Vmax’s and KM’s for hydroxyl radical formation were ∼5- to 10-fold higher than for H2O2 formation (Vmax’s = 9.29–102 pmol 2-OH-TPT/min/mg protein and KM’s = 8.85–250 μM). This may be due to the fact that the assay for hydroxyl radicals is less sensitive than the assay for H2O2 because of the short halflife and high reactivity of the hydroxyl radicals and the fact that Amplex red is a more sensitive fluorescent ROS indicator than 2-OH-TPT (36,37). We also noted that the maximal reaction rate of 2OHE2 was greater than other catechol estrogens in the 2-OH-TPT assay; the lowest activity was evident with 4OHE1. The reasons for these differences are not clear but may be due to availability of redox active iron in the hydroxyl radical assays. Catechols are known to chelate iron (57) and this may alter the conversion rate of H2O2 to hydroxyl radicals in the reaction mixes.

Also of interest was our finding that redox cycling by catechol estrogens stimulated the release of H2O2 from viable breast epithelial cells. Kinetic analysis of H2O2 release by the cells showed that the responses to each of the endogenous catechol estrogens was similar, as a percentage of Vmax and were generally consistent with the similarities in the kinetic constants of catechol estrogen-stimulated H2O2 generation in breast epithelial cell lysates (Table I). Catechol estrogen-stimulated release of H2O2 showed that redox cycling also occurs in intact cells. It also indicates that cellular ROS detoxification enzymes, such as various peroxidases and catalase, as well as antioxidants, are unable to limit increased intracellular H2O2 production formed during redox cycling (58). One can speculate that redox cycling may also cause the release of H2O2 by breast cells in vivo. If this is the case, then H2O2 formed during redox cycling has the potential to affect many cells in the tissue microenvironment. Depending on the localized concentrations of transition metals, highly mutagenic hydroxyl radicals may be generated which can further damage cells in breast tissue and may contribute to the development of cancer (59,60).

A question arises as to whether there are sufficient concentrations of the catechol metabolites of endogenous estrogens in human breast epithelial tissue to mediate redox cycling and generate cytotoxic ROS in vivo. Kinetic analysis of H2O2 production reveals that the rates of enzyme-mediated SQ formation are catechol estrogen concentration dependent. Because the concentration of cell lysate protein, and therefore number of catalytic sites, was held constant for each cell line, the measured Vmax is proportional to the turnover number (kcat) for catechol estrogen oxidation. This value is small, indicating poor catalytic efficiency at high substrate concentrations. Instead, the rate of this reaction during redox cycling is highly dependent on the value of the KM constant, indicating a high dependence on the catechol estrogen metabolite concentration. Since the apparent KM values of the catechol estrogen metabolites are in the micromolar range, we speculate that submicromolar concentrations of these endogenous metabolites generate significant quantities of H2O2. Although intracellular concentrations of estrogens are not known, they would be expected to be much higher in breast epithelial cells than in serum due to the presence of ERs. These high affinity-binding proteins would be expected to concentrate estrogens and their metabolites (15,42). Normal circulating serum estrogen levels in premenopausal females ranges from 75 to 2000 pg/ml (depending on the estrogen, the individual and the phase of the menstrual cycle) (61). As a lipophilic molecule, higher concentrations of estrogens may also be present in lipid compartments in cells including the microsomes where estrogen metabolism to catechols and redox cycling probably occurs (21).

It is also possible that breast epithelial cells synthesize their own catechol estrogens, as the enzyme which catalyzes the final step of estrogen synthesis (aromatase), is colocalized with enzymes governing estrogen metabolism to catechols (cytochromes P450 1A1 and 1B1) on the microsomal electron transport chain (28,62–65). Thus, the localized concentrations of catechol estrogens in the endoplasmic reticulum may be significantly greater than in other compartments of breast epithelial cells or in the serum and therefore, within a plausible range to generate ROS. The production of ROS by these cells is also necessarily dependent on the presence of NAD(P)H oxidase enzymes which have the capacity to mediate redox cycling (28,62). Our findings that redox cycling in the breast epithelial cells was inhibited by DPI confirm that flavoenzymes indeed mediate catechol estrogen redox cycling. Further studies are needed to characterize these enzymes and to determine if they play a role in generating ROS in breast tissues.

In summary, our studies demonstrate that endogenous catechol estrogens can redox cycle and generate ROS in breast epithelial cells. Production of ROS is not dependent on ERs or tumorigenic potential of the cells and may be an inherent property of epithelial cells in the breast. Catechol estrogen-stimulated ROS production by both cell lysates and intact cells is also independent of the species of catechol estrogen. Intact cells also generate ROS during catechol estrogen redox cycling. Sufficient levels of ROS can be generated to saturate intracellular antioxidant defense resulting in their release into the microenvironment of the breast. Our data provide further support for the idea that metabolism of endogenous estrogens to catechols and subsequent redox cycling may contribute to breast cancer development.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Figures 1–3 can be found at http://carcin.oxfordjournals.org/

Funding

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants ES005022 and AR055073. This work was also funded in part by the National Institutes of Health CounterACT Program through the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (award #U54AR055073).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the federal government. We thank Yun Wang for her assistance with the redox cycling assays using the CHO cell lines.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- E1

estrone

- E2

estradiol

- E3

estriol

- ER

estrogen receptor

- DPI

diphenyleneiodonium

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- HRT

hormone replacement therapy

- NADPH

reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- 2-OH-TPT

2-hydroxyterephthalate

- 2OHE2

2-hydroxyestradiol

- 2OHE3

2-hydroxyestriol

- 4OHE1

4-hydroxyestrone

- 4OHE2

4-hydroxyestradiol

- POR

cytochrome P450 reductase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SQ

semiquinone

References

- 1.Key T, et al. Endogenous sex hormones and breast cancer in postmenopausal women: reanalysis of nine prospective studies. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:606–616. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.8.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (Lyon France), World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer and IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (2007) Combined Estrogen-Progestogen Contraceptives and Combined Estrogen-Progestogen Menopausal Therapy. Lyon: IARC Press; 2007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Agency for Research on Cancer and World Health Organization. Hormonal Contraception and Post-menopausal Hormonal Therapy. Lyon: IARC; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inoh A, et al. Protective effects of progesterone and tamoxifen in estrogen-induced mammary carcinogenesis in ovariectomized W/Fu rats. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 1985;76:699–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noble RL, et al. Spontaneous and estrogen-produced tumors in Nb rats and their behavior after transplantation. Cancer Res. 1975;35:766–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shull JD, et al. Ovary-intact, but not ovariectomized female ACI rats treated with 17beta-estradiol rapidly develop mammary carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:1595–1601. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.8.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerlan V, et al. Nature of cytochromes P450 involved in the 2-/4-hydroxylations of estradiol in human liver microsomes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992;44:1745–1756. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90068-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato I, et al. Factors related to late menopause and early menarche as risk factors for breast cancer. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 1988;79:165–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1988.tb01573.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 women without breast cancer. Lancet. 1997;350:1047–1059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossouw JE, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malins DC, et al. Oxidative changes in the DNA of stroma and epithelium from the female breast: potential implications for breast cancer. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1629–1632. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.15.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang M, et al. Lipid peroxidation-induced putative malondialdehyde-DNA adducts in human breast tissues. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5:705–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Embrechts J, et al. Detection of estrogen DNA-adducts in human breast tumor tissue and healthy tissue by combined nano LC-nano ES tandem mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2003;14:482–491. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(03)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyd NF, et al. The possible role of lipid peroxidation in breast cancer risk. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1991;10:185–190. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90074-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liehr JG, et al. Estrogen-induced endogenous DNA adduction: possible mechanism of hormonal cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:5301–5305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li KM, et al. Metabolism and DNA binding studies of 4-hydroxyestradiol and estradiol-3,4-quinone in vitro and in female ACI rat mammary gland in vivo. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:289–297. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavigne JA, et al. The effects of catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibition on estrogen metabolite and oxidative DNA damage levels in estradiol-treated MCF-7 cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7488–7494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavalieri E, et al. Estrogens as endogenous genotoxic agents–DNA adducts and mutations. J. Natl Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2000;27:75–93. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavalieri E, et al. Catechol estrogen quinones as initiators of breast and other human cancers: implications for biomarkers of susceptibility and cancer prevention. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1766:63–78. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolton JL, et al. Role of quinoids in estrogen carcinogenesis. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1998;11:1113–1127. doi: 10.1021/tx9801007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolton JL. Quinoids, quinoid radicals, and phenoxyl radicals formed from estrogens and antiestrogens. Toxicology. 2002;177:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang F, et al. The major metabolite of equilin, 4-hydroxyequilin, autoxidizes to an o-quinone which isomerizes to the potent cytotoxin 4-hydroxyequilenin-o-quinone. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1999;12:204–213. doi: 10.1021/tx980217v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spink DC, et al. Metabolism of equilenin in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14:572–581. doi: 10.1021/tx000219r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolton JL, et al. Potential mechanisms of estrogen quinone carcinogenesis. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008;21:93–101. doi: 10.1021/tx700191p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weisz J, et al. Elevated 4-hydroxylation of estradiol by hamster kidney microsomes: a potential pathway of metabolic activation of estrogens. Endocrinology. 1992;131:655–661. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.2.1386303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liehr JG, et al. Cytochrome P-450-mediated redox cycling of estrogens. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:16865–16870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liehr JG. Role of DNA adducts in hormonal carcinogenesis. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2000;32:276–282. doi: 10.1006/rtph.2000.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolton JL, et al. Role of quinones in toxicology. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2000;13:135–160. doi: 10.1021/tx9902082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pisha E, et al. Evidence that a metabolite of equine estrogens, 4-hydroxyequilenin, induces cellular transformation in vitro. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14:82–90. doi: 10.1021/tx000168y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roy D, et al. Estrogen-induced generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, gene damage, and estrogen-dependent cancers. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 2007;10:235–257. doi: 10.1080/15287390600974924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russo J, et al. Estrogen and its metabolites are carcinogenic agents in human breast epithelial cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003;87:1–25. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00390-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, et al. Role of cytochrome P450 reductase in nitrofurantoin-induced redox cycling and cytotoxicity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;44:1169–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, et al. Distinct roles of cytochrome P450 reductase in mitomycin C redox cycling and cytotoxicity. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1852–1863. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fussell KC, et al. Redox cycling and increased oxygen utilization contribute to diquat-induced oxidative stress and cytotoxicity in Chinese hamster ovary cells overexpressing NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;50:874–882. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gray JP, et al. Paraquat increases cyanide-insensitive respiration in murine lung epithelial cells by activating an NAD(P)H:paraquat oxidoreductase: identification of the enzyme as thioredoxin reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:7939–7949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611817200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mishin V, et al. Application of the Amplex red/horseradish peroxidase assay to measure hydrogen peroxide generation by recombinant microsomal enzymes. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;48:1485–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mishin VM, et al. Characterization of hydroxyl radical formation by microsomal enzymes using a water-soluble trap, terephthalate. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004;68:747–752. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Twig G, et al. Real-time detection of reactive oxygen intermediates from single microglial cells. Biol. Bull. 2001;201:261–262. doi: 10.2307/1543355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heart E, et al. Rhythm of the beta-cell oscillator is not governed by a single regulator: multiple systems contribute to oscillatory behavior. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;292:E1295–E1300. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00648.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henderson B, et al. Endogenous and exogenous hormonal factors. In: Harris JR, editor. Diseases of the Breast. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preston-Martin S, et al. Increased cell division as a cause of human cancer. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7415–7421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jensen EV, et al. The estrogen receptor: a model for molecular medicine. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:1980–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Revankar CM, et al. A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science. 2005;307:1625–1630. doi: 10.1126/science.1106943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Madak-Erdogan Z, et al. Nuclear and extranuclear pathway inputs in the regulation of global gene expression by estrogen receptors. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008;22:2116–2127. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kleuser B, et al. 17-Beta-estradiol inhibits transforming growth factor-beta signaling and function in breast cancer cells via activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase through the G protein-coupled receptor 30. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;74:1533–1543. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.046854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yager JD, et al. Estrogen carcinogenesis in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:270–282. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bolton JL, et al. Quinoids formed from estrogens and antiestrogens. Methods Enzymol. 2004;378:110–123. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)78006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen L, et al. Bioreductive activation of catechol estrogen-ortho-quinones: aromatization of the B ring in 4-hydroxyequilenin markedly alters quinoid formation and reactivity. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:1093–1101. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.5.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cailleau R, et al. Breast tumor cell lines from pleural effusions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1974;53:661–674. doi: 10.1093/jnci/53.3.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soule HD, et al. A human cell line from a pleural effusion derived from a breast carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1973;51:1409–1416. doi: 10.1093/jnci/51.5.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soule HD, et al. Isolation and characterization of a spontaneously immortalized human breast epithelial cell line, MCF-10. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6075–6086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spink DC, et al. The effects of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin on estrogen metabolism in MCF-7 breast cancer cells: evidence for induction of a novel 17 beta-estradiol 4-hydroxylase. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1994;51:251–258. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(94)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lottering ML, et al. Effects of 17 beta-estradiol metabolites on cell cycle events in MCF-7 cells. Cancer Res. 1992;52:5926–5932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schutze N, et al. Catecholestrogens are MCF-7 cell estrogen receptor agonists. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1993;46:781–789. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(93)90319-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Halliwell B, et al. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gage JC. The action of paraquat and diquat on the respiration of liver cell fractions. Biochem. J. 1968;109:757–761. doi: 10.1042/bj1090757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iwahashi H, et al. The effects of caffeic acid and its related catechols on hydroxyl radical formation by 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, ferric chloride, and hydrogen peroxide. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1990;276:242–247. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90033-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klaunig JE, et al. Oxidative stress and oxidative damage in carcinogenesis. Toxicol. Pathol. 2010;38:96–109. doi: 10.1177/0192623309356453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Halliwell B. Oxygen and nitrogen are pro-carcinogens. Damage to DNA by reactive oxygen, chlorine and nitrogen species: measurement, mechanism and the effects of nutrition. Mutat. Res. 1999;443:37–52. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ueda J, et al. Reactive oxygen species generated from the reaction of copper(II) complexes with biological reductants cause DNA strand scission. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998;357:231–239. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Caron P, et al. Profiling endogenous serum estrogen and estrogen-glucuronides by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:10143–10148. doi: 10.1021/ac9019126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shimada T, et al. Interactions of mammalian cytochrome P450, NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase, and cytochrome b(5) enzymes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;435:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lu AY, et al. Resolution of the cytochrome P-450-containing omega-hydroxylation system of liver microsomes into three components. J Biol. Chem. 1969;244:3714–3721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sarabia SF, et al. Mechanism of cytochrome P450-catalyzed aromatic hydroxylation of estrogens. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1997;10:767–771. doi: 10.1021/tx970021f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Badawi AF, et al. Role of human cytochrome P450 1A1, 1A2, 1B1, and 3A4 in the 2-, 4-, and 16alpha-hydroxylation of 17beta-estradiol. Metabolism. 2001;50:1001–1003. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.25592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.