Abstract

The spontaneous folding of two Neisseria outer membrane proteins, opacity-associated (Opa)60 and Opa50 into lipid vesicles was investigated by systematically varying bulk and membrane properties. Centrifugal fractionation coupled with sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis mobility assays enabled the discrimination of aggregate, unfolded membrane-associated, and folded membrane-inserted protein states as well as the influence of pH, ionic strength, membrane surface potential, lipid saturation, and urea on each. Protein aggregation was reduced with increasing lipid chain length, basic pH, low salt, the incorporation of negatively charged guest lipids, or by the addition of urea to the folding reaction. Insertion from the membrane-associated form was improved in shorter chain lipids, with more basic pH and low ionic strength; it is hindered by unsaturated or ether-linked lipids. The isolation of the physical determinants of insertion suggests that the membrane surface and dipole potentials are driving forces for outer membrane protein insertion and folding into lipid bilayers.

Introduction

Membrane protein structural and in vitro functional studies rely on synthetic membrane mimics (e.g., detergents and liposomes) to stabilize the protein fold and maintain function. Currently, the forces which dictate membrane protein stability are not well understood and investigators empirically screen mimics and solution conditions conducive to maintaining proper fold and function. Additional complexity, compared to soluble proteins, arises from the heterogeneity of the native lipid environment, and the diverse properties of membrane proteins (e.g., secondary structure and the extent of soluble domains). Studies of membrane protein folding in synthetic membrane mimics provides

-

1.

Methods for preparing membrane proteins for structural and functional studies and

-

2.

Knowledge of the physical forces involved in membrane protein stability.

Progress toward understanding membrane protein folding and stability has resulted predominantly from the study of two membrane proteins representing the two major structural classes: bacteriorhodopsin (α-helical) (1–3) and Escherichia coli outer membrane protein (Omp)A (β-barrel) (4–6). However, as more membrane proteins are prepared for study, the difficulty of determining conditions amenable for membrane protein folding (and conditions optimal to study their structure and function) has become evident.

In vitro, a small number of β-barrel outer membrane proteins (OMPs) have demonstrated insertion and folding directly into lipid vesicles from a urea-denatured state. The first and most-studied OMP to show lipid vesicle insertion is OmpA, for which the physical determinants (7–10), kinetics (7,11,12), and thermodynamics (13–15) of folding have been investigated (reviewed in the literature (4–6,16)). Folding of OmpF (17), OmpX (18), and VDAC (19) into lipid vesicles was also reported, as were kinetic measurements for the folding of FomA (20) and thermodynamic measurements for the folding of PagP (21).

Varied folding conditions were used for each of these proteins, and a systematic study to optimize lipid folding for nine OMPs (including OmpA, OmpF, OmpX, and PagP mentioned above) found the OMPs to have widely different folding efficiencies in any single bilayer environment (22). Therefore, the specific protein and membrane properties that dictate folding are not well understood. Investigations of these folding determinants are necessary not only to enhance basic knowledge of membrane protein folding, but also to accelerate optimized protocols for new lipid-reconstituted OMP systems. The resulting proteoliposomes are useful for structural and functional studies in the nativelike lipid environment, and have possible applications for liposome-based therapeutic or vaccine delivery (23,24).

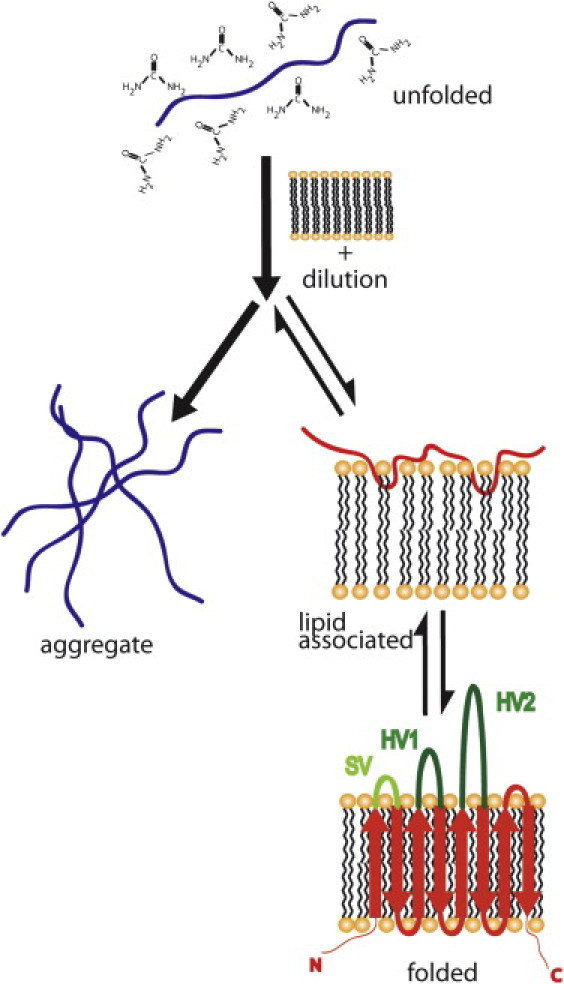

Despite variable folding conditions and efficiencies, a generalized model of spontaneous folding has emerged and is represented in Fig. 1. Upon dilution of denaturant in the presence of lipid vesicles, the OMP either aggregates or associates with the lipid bilayer. Lipid-associated protein may fully insert and fold, or may remain unfolded (or partially folded) in a lipid-associated state. A compilation of data from sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) migration assays (7,11,12), circular dichroism (5,10,12), and fluorescence experiments (10–12,25,26) have led to a proposed mechanism for OmpA folding into lipid bilayers (schematically shown Fig. 1). OmpA appears to bind to the membrane surface in a fast step (on the order of seconds; see the lipid-associated form in Fig. 1). Then, in one or more slow steps (minutes to hours, depending on conditions), the protein inserts and folds in concert across the bilayer (11,15,25,26). The thermodynamics and kinetics of each of these steps are modulated by physical properties of the solvent, lipid, and membrane protein; however, the specific contributions of each are not fully understood.

Figure 1.

Proposed pathways for β-barrel folding into lipid bilayers. The protein is unfolded in 8 M urea and diluted with lipid vesicles. Upon dilution, the protein can aggregate or associate with the lipid, insert, and fold. In the text, lipid-associated refers to unfolded protein at the surface of the bilayer or partially inserted intermediates and folded or lipid inserted refers to fully folded protein. The putative topology for the eight-stranded β-barrel proteins Opa60 and Opa50 is shown. The hypervariable loops proposed to be involved in host receptor recognition are colored green and labeled HV1 and HV2. The label SV indicates a semivariable loop. See Fig. S1 for the protein sequences and alignment of Opa50 and Opa60.

In this study, centrifugal fractionation is coupled with the previously employed SDS-PAGE mobility assays allowing the discrimination of aggregate, unfolded membrane-associated, and folded membrane-inserted protein states (Figs. 1 and 2) during the spontaneous folding of two OMP proteins, opacity-associated (Opa)60 and Opa50 (also called OpaI and OpaA, respectively). These eight-stranded OMPs, from Neisseria gonorrhea MS11 (Fig. 1, folded), bind a variety of human cell receptors to induce phagocytosis of the bacterium. Opa60 and Opa50 have nearly identical sequence in the β-barrel region but highly variable extracellular loops. The investigation of Opa50 and Opa60 spontaneous folding into lipid vesicles reveals Opa proteins associate with the bilayer almost immediately after their rapid dilution, but in contrast to OmpA, insertion happens on the timescale of days, rather than minutes or hours.

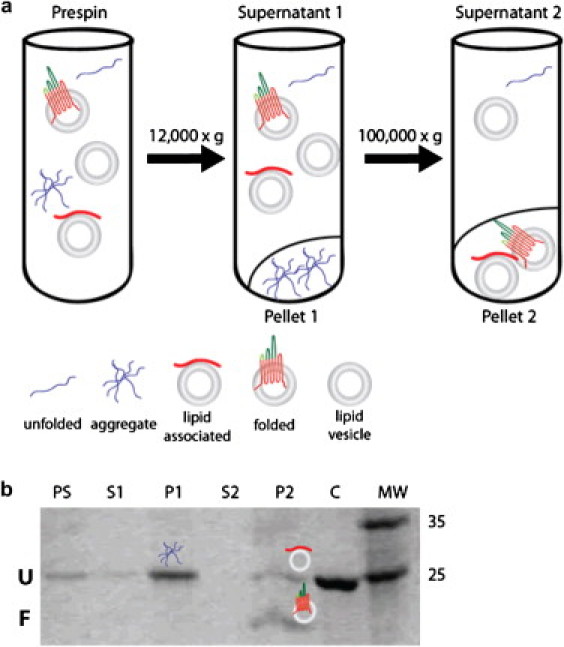

Figure 2.

Centrifugal fractionation and SDS-PAGE of aggregate- and lipid-vesicle-associated Opa. (a) Centrifugation is used with SDS-PAGE to monitor folding and to report on relative portions of aggregate, lipid-associated, and folded protein. Initial centrifugation removes protein aggregate. A second ultracentrifugation pellets lipids with associated or folded protein. (b) All fractions are analyzed by SDS-PAGE; folded protein is differentiated by a gel migration shift (U identifies the unfolded protein band and F labels the folded protein band). The lane labels PS, S, P, C, and MW refer to prespin, supernatant, pellet, control (which is Opa unfolded in 8 M urea without lipids), and molecular weight marker (expressed in kDa). Total fraction folded is the amount of folded protein divided by total protein (lipid-associated + aggregate + folded protein), fraction aggregate is the amount of aggregate divided by total protein, and lipid fraction folded refers to the fraction of protein folded in the lipid pellet only (folded/(lipid-associated + folded)), thus the amount of lipid-associated protein (not explicitly shown in figures) is anti-correlated to the lipid fraction folded.

Also, unlike OmpA (27), Opa proteins show a high propensity for self-aggregation, which is reduced with increased lipid chain length, negative membrane surface or protein charge, low salt, and urea. Centrifugal fractionation allowed the unfolded populations (aggregate versus membrane-associated) to be separated so that the conditions that favor membrane insertion and folding were resolved from those that influence aggregation. Opa protein insertion and folding from the unfolded membrane-associated state is favored with shorter chain lipids, basic pH, and low ionic strength. The collective results imply that slowing the formation of or destabilizing the unfolded membrane-associated state increases both aggregation and folding into the lipid bilayer and that the membrane surface and dipole potentials are important in the stability and/or kinetics of the membrane-associated state. The results provide greater mechanistic insight to OMP folding and facilitate the development of new OMP-lipid folding systems.

Materials and Methods

Folding by rapid dilution

Concentrated (15 mg/mL) Opa50 or Opa60 in urea (for details of cloning, expression, and purification, see the Supporting Material) were diluted ≈100-fold by stepwise addition (2.5 μL at a time, 10 inversions between each addition) into 1-mL aliquots of prepared liposomes (details are given in the Supporting Material) and incubated at 37°C before analysis. Hydrophobic thickness was also studied at 60°C to be above the gel transition temperature of the longer-chain lipids (see Table S3 in the Supporting Material, which lists transition temperatures of lipids used in this study). Unless otherwise indicated, incubation time was three days with a final Opa concentration, lipid concentration, and molar lipid/protein ratio of 6 μM, 2.4 mM, and 400:1, respectively.

Folding analysis by centrifugation

Fig. 2 a outlines the procedure used to fractionate aggregate and lipid-associated folded and unfolded species. Briefly, samples were centrifuged in an Optima Max XP centrifuge (Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA) at 12,000 × g for 20 min to remove protein aggregate. Pellets were resuspended in 60 μL resuspension buffer (30 mM Tris, pH 7.3, 150 mM NaCl). The supernatant was centrifuged at 150,000 × g for 2 h to pellet liposomes containing or associating with protein, and this pellet was also resuspended in 60 μL resuspension buffer. Aliquots of supernatants and pellets were assessed by SDS-PAGE.

Folding monitored by SDS-PAGE

The folding reaction in each aliquot (10 μL) of the prespin sample, both supernatants, and both resuspended pellets, was quenched with 5 μL 3XSDS gel-loading buffer. Twelve microliters of each sample were loaded onto a precast 10% acrylamide gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) without boiling. After electrophoresis, gels were stained with Coomassie blue, and digital images were recorded and analyzed with ImageJ software (28) (for details, see the Supporting Material and Fig. 2 b). The total fraction folded was calculated by Eq. 1,

| (1) |

where numerical values for each state are in relative pixels (normalized intensity x area). Folded and lipid-associated proteins are quantified as relative pixels of the folded and unfolded bands, respectively, observed in P2 (labeled F and U in Fig. 2 b). Aggregate refers to the relative pixels measured in P1 (Fig. 2 b), and the fraction aggregate was calculated by Eq. 2,

| (2) |

Lipid fraction folded was calculated by Eq. 3 as

| (3) |

Lipid fraction folded is, therefore, anticorrelated to the amount of lipid-associated protein, such that the lipid fraction folded plus fraction of lipid-associated protein (not explicitly shown in figures) must total one. Error bars are the standard deviation of at least three separate experiments.

Although migration on SDS-PAGE has been used to assess folding for many OMPs, the function of the Opa folded species was assessed with a binding pull-down centrifugal assay. Both Opa60 and Opa50 bound their cognate receptors, CEACAM N-domain and heparin (a competitive inhibitor of heparansulfate proteoglycan receptor binding), respectively, in a concentration-dependent manner (data not shown).

Results and Discussion

Opa proteins do not fold under conditions reported for OmpA

Initially, conditions successful for the folding of OmpA were investigated for the folding of Opa proteins due to their similar size and topology. Because Opa proteins fold slowly (on the order of days) into detergent micelles (C. Reyes, D. Fox, R. Lo, and L. Columbus, unpublished observations), folding was monitored at 1, 24, and 72 h by SDS-PAGE. Sonicated small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) were used instead of extruded large unilamellar vesicles for all folding trials because SUVs were previously shown to induce higher OMP folding efficiency (12,22). Despite success with OmpA, Opa60 and Opa50 did not fold into SUVs of diC14PC in phosphate buffer at pH 7.3 (9) or glycine buffer at pH 10 (10); or DOPC in glycine buffer at pH 8.3 with 150 mM NaCl (11); or POPC or 92.5/7.5 POPC/POPG in glycine buffer at pH 10 (15) at any time point (see Table S2).

Opa proteins also did not fold efficiently into SUVs prepared from E. coli total lipid extract or polar extract at pH 10 or 12 (though the extract composition is similar to that of native Neisseria membranes without the lipooligosaccharide of the outer leaflet) (29) (see Fig. S2 in the Supporting Material). Previous work on OmpA and other OMPs found that OMPs generally do not fold into E. coli lipid extracts, into synthetic lipids mixed to resemble the native bilayer composition, nor into lipids prepared with added lipopolysaccharide (7,22).

Lipid carbon-chain length modulates Opa aggregation, lipid-association, and folding, with short chain lipids destabilizing the lipid-associated state

The failure of Opa proteins to fold in previously published conditions led to a systematic screening of bulk solution and lipid properties. Previous studies demonstrated that OMP folding depends on the bilayer hydrophobic thickness (12,15,22), thus, Opa60 and Opa50 folding were investigated in SUVs of saturated phosphocholine lipids with aliphatic chains of 10 (the minimum chain length that forms vesicles (30)) to 18 carbons in length at 37 and 60°C, to be above the gel transition temperature of the longer chain (diC16- and diC18PC) lipids. Consistent with OmpA (9), Opa proteins did not fold in lipids below their gel transition temperatures. Folding was not observed in diC10-, diC12-, or diC14PC lipids at 60°C (see Fig. S3). Fig. 3 shows data collected at 37°C for all lipids except diC16- and diC18PC, for which results are shown at 60°C.

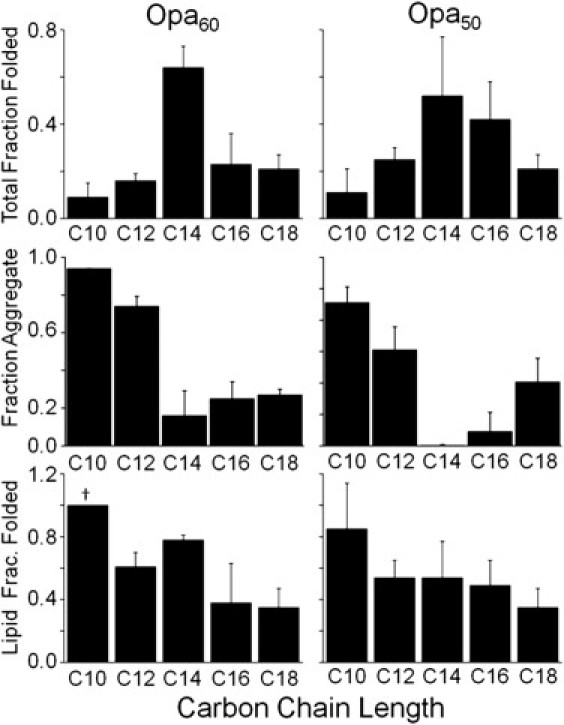

Figure 3.

Opa60 and Opa50 folding, aggregation, and lipid insertion vary with lipid carbon chain length. Opa protein folding in lipid vesicles of saturated phosphocholine with different carbon chain lengths was evaluated after ultracentrifugation and SDS-PAGE with densitometric analysis. All lipids (2.4 mM in 10 mM sodium borate pH 12 and 1 mM EDTA) were above their melting temperatures for the folding reaction: diC10-diC14PC at 37°C and diC16- and diC18PC lipids at 60°C. The final Opa concentration and molar lipid/protein ratio were 6 μM and 400:1, respectively. For definitions of fractions, see Fig. 2 and text. For all folding assessments: (∗) folding not observed in at least three separate experiments; (†) observed value constant across replicates; and (‡) folding seen in only one of three replicates; deviation not calculated. Error bar not visible is within line of column.

Separation of aggregate, lipid-associated, and folded protein with centrifugal fractionation (Fig. 2) before SDS-PAGE revealed that both aggregation and the lipid fraction folded decreased with increasing chain length (see Fig. 3 and summary in Table 1). The highest total fraction folded and the least protein aggregation was observed in diC14PC for both Opa50 and Opa60. Despite the high total fraction folded, the diC14PC lipid fraction consistently contained 22 ± 3% unfolded membrane-associated protein. Resuspension, centrifugation, and further washing of the lipid fraction pellet with buffer, buffer containing 4 M urea, or buffer with high concentrations of salt did not remove the unfolded membrane-associated protein. In short-chain diC10PC lipids, the total fraction folded was minimal (Fig. 3) due to a large amount of aggregation. However, the lipid fraction folded was greatest in the diC10PC lipids, with little or no unfolded membrane-associated protein observed for Opa60 and Opa50, respectively. Thus, if aggregation is excluded, the fraction folded decreases with lipid chain length as was reported for other OMPs (22).

Table 1.

Summary of aggregation and folding in the environments investigated

| ↑ Condition | Total fraction folded | Fraction aggregate | Lipid fraction folded |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon chain length | ↑/↓∗ | ↓ | ↓ |

| pH | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

| Ionic strength | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ |

| Charged lipids | ↑/↓† | ↓ | ↓ |

| Unsaturated lipids | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ |

| Urea | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

C10-C14↑, C14-C18↓.

Folding improved in diC10PC but worsened in diC14PC.

These results indicate that lipid chain length modulates aggregation, lipid-association, and folding. Because the lipid-associated state is between the aggregate and lipid folded protein, the results can be explained if the membrane (specifically the chain length) is modulating the kinetics or stability of the lipid-associated state. One possible mechanism is that shorter chain lipid vesicles have different surface properties than longer chain lipid vesicles. In the liquid-crystalline phase, increasing lipid chain length increases the van der Waals attractions between the aliphatic chains, which overcome the entropic repulsion from packing the lipids (31). As a result, at a given temperature, shorter chain lipids have increased disorder closer to the headgroup (i.e., the plateau region in deuterium NMR experiments) and a larger area per headgroup compared to longer chain lipids (31,32).

The increase in area per headgroup alters the effective water concentration at the bilayer surface with ∼0.5 M less water for every two carbons in length (33). Thus, surface properties that vary with chain length (area per headgroup, chain ordering, and headgroup hydration) appear to destabilize or slow the formation of the membrane-associated state, leading to both greater aggregation and an increase in the lipid fraction folded in shorter chain lipids. This trend is slightly reversed in diC16PC and diC18PC lipids. However, data for these lipids was collected at 60°C, to be above their gel transition temperatures. The increase in temperature increases the lipid surface area (though chain length decreases it) (31), as well as Opa protein dynamics, either of which may explain the increase in aggregation with these lipids, as well as the increased aggregation and lack of folding in the shorter chain lipids at 60°C (see Fig. S3).

Insight into the membrane-associated state may be insinuated by the difference in the folding of Opa50 and Opa60. A greater fraction aggregate was generally observed for Opa60 than Opa50. The two Opa proteins are nearly identical in the β-barrel transmembrane sequence, but have sequence variation in three of the four extracellular loops. These sequence differences appear to modulate the extent of aggregation observed, with Opa60 aggregating more in these lipid systems than Opa50. Previous studies have indicated that increasing the pH and, thus, the negative charge of the protein can reduce aggregation presumably due to electrostatic repulsion between protein molecules (22,27). However, Opa60 (pI ≈ 9.6; net charge ≈−31 at pH 12) is more negatively charged than Opa50 (pI ≈ 9.9; net charge ≈−28 at pH 12) (http://www.scripps.edu/∼cdputnam/protcalc.html; sequences are shown in Fig. S1).

In addition, the observed aggregation is chain-length-dependent, suggesting that the interaction with the membrane surface differs between Opa60 and Opa50. Hence, for shorter chain lipids, aggregation appears to be dependent not only on the driving forces between protein molecules, but also on the kinetics and/or thermodynamics of protein association with the membrane.

Opa folding improves with basic pH and low ionic strength

To investigate the role of electrostatic interactions in Opa folding, pH and salt dependencies were investigated in diC14PC and diC10PC vesicles (Fig. 4), because these lipids had the greatest total fraction folded (diC14) or lipid fraction folded (diC10). Folding was investigated while varying pH from 3–12. Zwitterionic phosphocholine bilayers are net-neutral from pH 5–12, and positive at pH 3. There are conflicting reports about lipid hydrolysis at basic pH (34,35); regardless, the bilayer structure is destabilized upon lipid hydrolysis and the SUV particle size and distribution undergoes morphological changes such as fusion and micellization (34). For the SUV preparations at pH 12 in this study, thin layer chromatography indicated hydrolysis was present but not complete (data not shown); however, the dynamic light scattering of the liposomes at pH 12 (incubated for three days) indicated the liposomes were intact and similar in size to those prepared at other pH values (see Table S1).

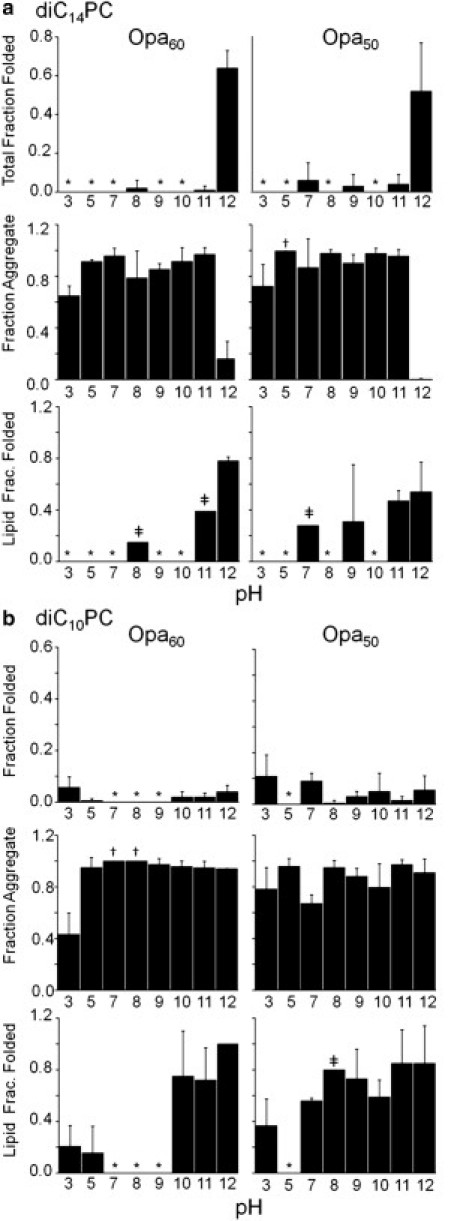

Figure 4.

pH impacts Opa folding and insertion. Opa60 and Opa50 folding, aggregation, and lipid insertion in diC14PC (a) or diC10PC (b) lipid vesicles (2.4 mM with 1 mM EDTA) with varying pH (10 mM citrate, pH 3 and 5; 10 mM bis-tris, pH 7; 10 mM Tris, pH 8; 10 mM glycine, pH 9 and 10; 10 mM sodium borate, pH 11 and 12). The final Opa concentration and molar lipid/protein ratio were 6 μM and 400:1, respectively. Opa protein folding was assessed after ultracentrifugation and SDS-PAGE with densitometric analysis. For definitions of fractions, see Fig. 2 and text and for definition of symbols, see Fig. 3 legend.

In general, aggregation was high except at pH 3 and 12, with a major decrease in aggregation in diC14PC at pH 12. Previous studies of OmpA (10) and other OMPs (22) found that the total fraction folded increased with basic pH, attributed to a decrease in protein aggregation due to increasing the negative protein charge (5,27). These investigations were conducted up to pH 10 on proteins with pI values between 5 and 6 compared to pI values between 9 and 10 for Opa proteins. Centrifugal fractionation in this study revealed that, in addition to preventing aggregation, basic pH increased the lipid fraction folded for both Opa50 and Opa60 in diC14PC. The effect on the lipid fraction folded in diC10PC was different for Opa50 and Opa60 with a dramatic transition between pH 9 (folded protein not observed) and 10 (75 ± 35%) for Opa60 and minimal observed pH dependence for Opa50. Thus, the results suggest that an increase in protein negative charge increases the rate of folding, destabilizes the membrane-associated state, and/or stabilizes the folded state.

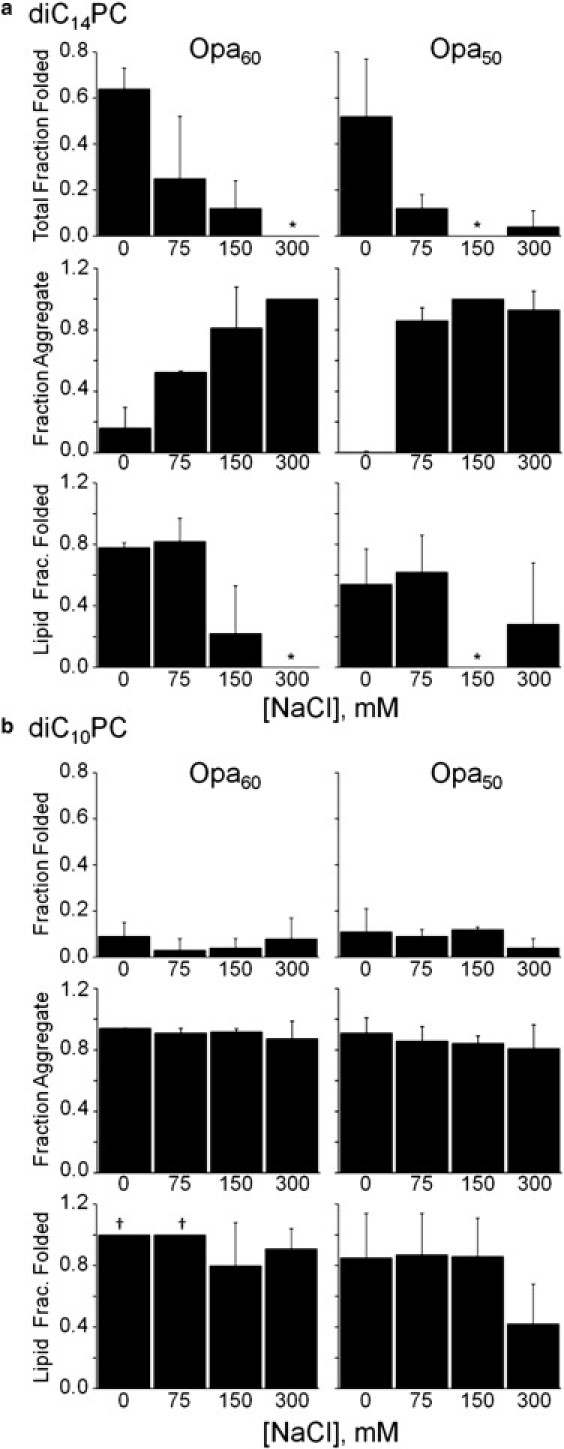

To further probe the role of electrostatic interactions, the influence of ionic strength on folding and aggregation in diC14- or diC10PC vesicles was investigated at pH 12. In diC14PC vesicles, Opa60 and Opa50 total fraction folded decreased with increasing NaCl concentration. Aggregation in diC14PC lipids was minimal without salt and significantly increased above 75 mM NaCl (Fig. 5 a). Increasing ionic strength also decreased the lipid fraction folded, implying that higher ionic strength stabilized the unfolded lipid-associated state, destabilized the folded state, and/or decreased the rate of protein folding. In diC10PC, significant changes in the total or lipid fraction folded were not observed (Fig. 5 b). For Opa60 in diC10PC, aggregation slightly decreases at higher ionic strength, consistent with the slight pH dependence observed in diC10PC (Fig. 4) and indicative that repulsion due to negative charges is not the only factor modulating the aggregation propensity of OMPs (as discussed above).

Figure 5.

Ionic strength impacts Opa folding and insertion. Opa60 and Opa50 folding, aggregation, and lipid insertion in diC14PC (a) or diC10PC (b) lipid vesicles as a function of NaCl concentration at pH 12 (10 mM sodium borate and 1 mM EDTA). The final Opa concentration and molar lipid/protein ratio were 6 μM and 400:1, respectively. Opa protein folding was assessed after ultracentrifugation and SDS-PAGE with densitometric analysis. For definitions of fractions, see Fig. 2 and text; for definition of symbols, see Fig. 3 legend.

The pH and ionic strength data suggest that negative protein charge prevents protein aggregation and increases lipid fraction folded. That negative protein charge may facilitate protein folding into lipids (in addition to preventing aggregation) has not previously been considered due to the lack of separation of aggregate and unfolded membrane-associated protein. The importance of protein negative charge in insertion and folding into bilayers may be analogous to the insertion and permeability of hydrophobic anions for which the large dipole potential in lipid membranes (see Fig. S4) plays a significant role. In phosphocholine lipid vesicles, the dipole potential is estimated to be +300 mV (36,37), and is thought to arise from the conformation and orientation of the lipid molecules, particularly in the headgroup region, as well as the preferential orientation of associated polarized waters (36,38,39). Because of the positive dipole potential, hydrophobic anions permeate membranes up to 106 times faster than hydrophobic cations (36); similarly, the insertion of negatively charged protein might be facilitated as well.

A second contributing factor may be the penalty of desolvating charges upon membrane association and penetration (40). As pH increases above the protein pI (>9), the protein becomes more negative, and between pH 11 and 12 (where the greatest increase in folding is observed), the change is due to the deprotonation of basic groups (i.e., positive charge is removed) such that the total number of charges on the protein decreases. By diminishing the number of charged residues on the protein, the desolvation penalty associated with membrane association and insertion is decreased.

Negative lipid surface potential favors the membrane-associated state

The importance of the lipid-associated state in modulating aggregation and lipid fraction folded suggests that the membrane surface potential may influence the OMP folding process. Therefore, the surface potential was modulated by titrating negatively charged phosphoglycerol (PG) lipids, into phosphocholine (PC) vesicles at pH 10 and 12 (see Fig. S5). A maximum of 50% PG lipid was used, because lipid aggregation occurs in vesicles containing >50% charged lipid (41). In conditions for which significant Opa aggregation is observed (Opa60 at pH 12 in diC10PC and pH 10 in both diC10- and diC14PC), increasing PG decreased aggregation, but did not significantly change the already high lipid fraction folded. The one exception to this trend was Opa50 in diC14PC at pH 12, where increases in PG increased aggregation and decreased the total fraction folded.

Lipid vesicles containing PG lipids carry a negative surface potential, in addition to the positive internal dipole potential (see Fig. S4). Application of the Gouy equation to the PC/PG lipid systems yields surface potentials of zero, −60 mV, −100 mV, and −140 mV for pure PC, 90:10 PC/PG, 75:25 PC/PG, and 50:50 PC/PG, respectively. Thus, a more negative surface potential increases the population of the lipid-associated state in lipid systems in which significant aggregation is observed in the pure PC membrane. In addition, the general decrease in lipid fraction folded with a more negative surface potential is consistent with the hypothesis that the negatively charged surface favors the lipid-associated state.

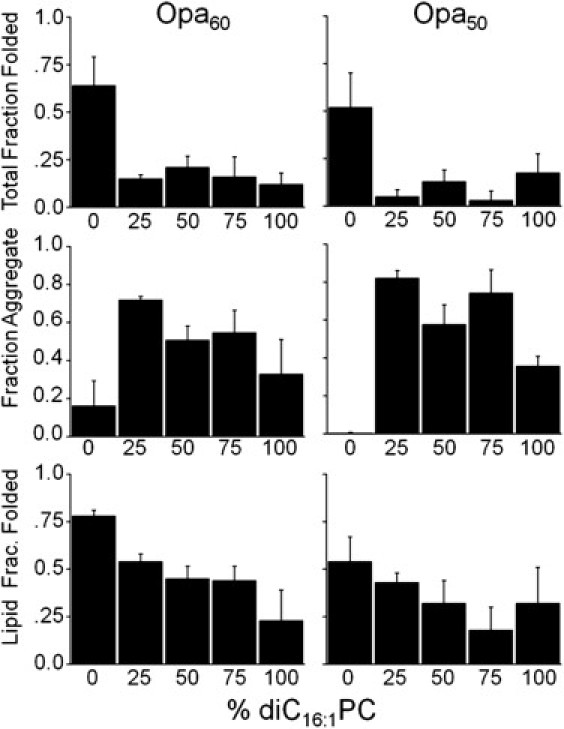

Unsaturated lipids do not improve the folding of Opa proteins

Membrane fluidity increases with the addition of unsaturated lipids by decreasing the van der Waals packing between lipid chains and increasing the disorder of the chains. As a result, the lipid gel-liquid transition (melting) temperature increases with saturation (e.g., 42°C for diC16:0PC compared to −36°C for diC16:1PC) (42,43). Because OMP folding does not occur with gel-phase lipids and because insertion and folding occur more rapidly in more fluid short-chain lipids (5), unsaturated diC16:1PC guest lipids (which have a similar hydrophobic thickness to diC14PC; see Table S3) were titrated into diC14PC vesicles to increase membrane fluidity and potentially improve folding. Instead, the total fraction folded decreased with unsaturated guest lipids. Saturated/unsaturated mixed vesicles induced large amounts of protein aggregation, and the lipid fraction folded decreased with increasing amounts of diC16:1PC (Fig. 6). Similar results were obtained in diC14:1PC vesicles, when compared to saturated PC vesicles of similar hydrophobic thickness (see Fig. S6).

Figure 6.

Opa folding dependence on unsaturated guest lipid in saturated lipid vesicles. Opa60 and Opa50 folding, aggregation, and lipid insertion with varying mol % diC16:1PC in diC14PC. The final Opa concentration and molar lipid/protein ratio were 6 μM and 400:1, respectively. Opa protein folding was assessed after ultracentrifugation and SDS-PAGE with densitometric analysis. For definitions of fractions, see Fig. 2 and text.

The effect of membrane fluidity on aggregation is likely due to either destabilization of the membrane-associated protein and/or a decrease in the rate of association. As with chain length, this might be explained by the increased area per headgroup (and concomitant change in water concentration) of the unsaturated lipids (44). In addition, and possibly resulting from the increased area per headgroup, unsaturation decreases the membrane dipole potential to ≈+180 mV in pure diC16:1PC lipids, compared to ≈+300 mV in saturated diC14PC (44). These differences in membrane properties could explain the lack of folding observed in unsaturated lipids, despite their fluidity. The role of the dipole potential and protein insertion is further implicated by the lack of Opa protein folding in ether-linked lipids despite relatively high Opa protein folding efficiency in the ester-linked counterparts (see Fig. S7). The dipole potential is smaller for the ether-linked lipids than for the ester-linked lipids (e.g., ether-linked DOPC is ≈ 120 mV less than ester-linked DOPC (36)).

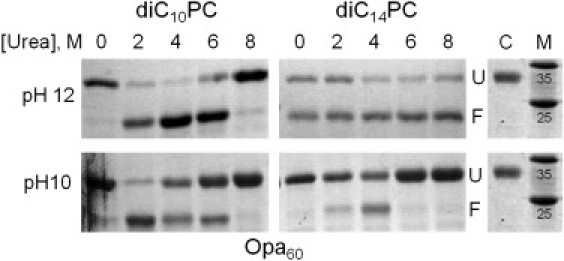

Urea facilitates Opa protein folding, especially in short-chain lipids

Aggregation is a major competing pathway in many of the folding conditions studied. Because chaotropes, such as urea, are well known to prevent protein aggregation, Opa60 folding in diC10- or diC14PC vesicles at pH 10 or 12 was investigated in the presence of urea (Fig. 7). For conditions in which high amounts of aggregate were observed without urea in the folding reaction (diC10- or diC14PC at pH 10 and diC10PC at pH 12; Fig. 4), the amount of folded protein increased with 2–4 M urea. The amount of folded Opa in diC14PC at pH 12 (the condition for which significant aggregation was not detected) did not drastically increase with the addition of urea. Optimal folding (>95% fraction folded) was observed in diC10PC vesicles, at pH 12, in 4 M urea.

Figure 7.

Urea in Opa protein folding. SDS-PAGE results of Opa folding at pH 12 or 10 in diC10PC or diC14PC lipid vesicles with varying molar concentrations of urea in the folding reaction. Unfractionated samples shown. The labels U and F designate unfolded and folded species, respectively. Unfolded control (Opa protein in 8 M urea with no lipids) is labeled C; molecular weight marker is labeled M and weights expressed are in kDa.

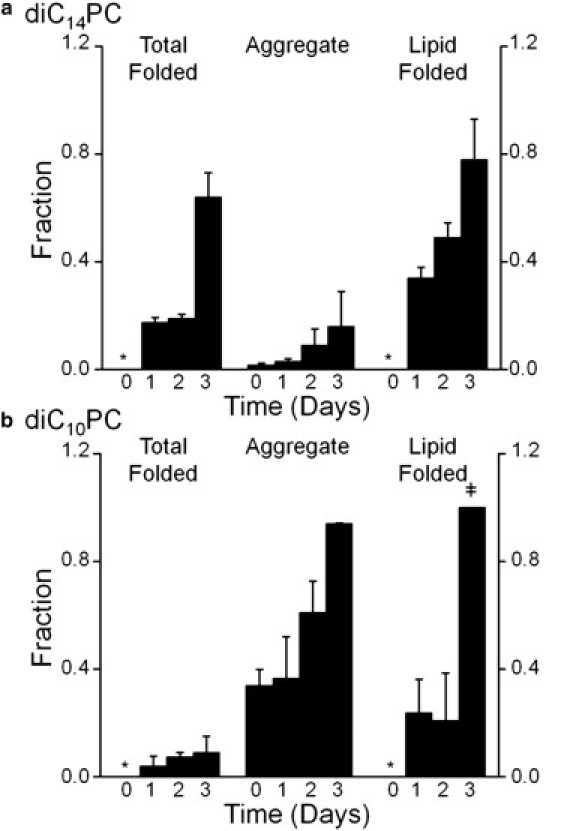

Opa proteins associate with lipid vesicles within minutes, but insert and fold over days

Opa protein aggregation, lipid association, and folding were measured by SDS-PAGE immediately after the protein was added to the vesicles (day 0) and in 24 h increments for the next three days. Folding was not observed at the initial time point, but was observed after one day, and continued to increase over the course of the three days (Fig. 8). Lipid-associated protein is observed for diC10- and diC14PC vesicles beginning at day 0, indicating that Opa protein membrane association is fast, but folding is a slow process even in short-chain lipids. Although aggregation is observed immediately after the addition of Opa to diC10PC vesicles, an increase in aggregation is observed over time, which may be attributed to instability of membrane-associated protein in short chain lipids. The SDS-PAGE experiments report on the unfolded and folded populations, but not on the intermediates which are denatured by SDS and, therefore, migrate as unfolded.

Figure 8.

Opa folding kinetics by SDS-PAGE. Opa60 folding, aggregation, and lipid insertion immediately after protein addition to vesicles (day 0) and after one, two, or three days of incubation in diC14PC (a) or diC10PC (b) lipid vesicles. The final Opa concentration and molar lipid/protein ratio were 6 μM and 400:1, respectively. For definitions of fractions, see Fig. 2 and text; for definition of symbols, see Fig. 3 legend.

By contrast, changes in intrinsic protein fluorescence may be used to qualitatively track intermediates between the initial protein association with the membrane surface to the final folded protein. In diC14PC (where aggregation is minimal), the intrinsic fluorescence of Opa60 exhibits a blue-shift and sharp increase in intensity within the mixing time (<2 min) of adding the protein to the lipid, indicating the tryptophan residues enter an apolar environment. Then, the intensity increases over the time course of the experiment (45) (see Fig. S8).

The fluorescence data suggests that Opa tryptophan residues interact and at least partially insert into the lipid vesicles quickly, and results from SDS-PAGE and the gradual increase in fluorescence intensity indicate that complete Opa protein folding takes days. For OmpA in longer-chain lipids, slow rate constants were improved by increasing the lipid/protein ratio to 1600:1 (12). For Opa proteins, the amount of aggregate, lipid-associated, or lipid-folded protein did not change when the lipid/protein ratio increased from 400:1 to 1600:1 by using a high concentration of lipids, or when it increased to 800:1 by using a more dilute stock of Opa protein (see Fig. S9).

Conclusions

The slow nature of Opa folding and the use of a centrifugal fractionation assay allowed an initial investigation into the physical properties important to β-barrel membrane protein aggregation, membrane association, and folding into lipid. Previous studies investigated the total fraction folded and the soluble aggregation tendencies before association and insertion, but did not isolate physical determinants in each step. Cumulatively, the data suggest that slowing the formation of or destabilizing the unfolded membrane-associated state increases both protein aggregation and lipid fraction folded. Table 1 summarizes the effects of each condition on total fraction folded, aggregation, and lipid fraction folded.

Protein aggregation is reduced with increasing lipid chain length, basic pH, low salt, the incorporation of negatively charged guest lipids, or by the addition of urea to the folding reaction. Insertion from the membrane-associated form is improved in shorter chain lipids, with more basic pH and low ionic strength, and is hindered by unsaturated or ether-linked lipids. The isolation of the physical determinants of insertion suggests that the membrane surface potential and dipole potential are important driving forces to OMP protein folding.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant No. RO1GM087828), the Jeffress Memorial Trust, a Double Hoo Research Grant by the Center for Undergraduate Excellence at the University of Virginia (to A.H.D. and J.C.H.), and the Charles Henry Leach, II Foundation (to J.C.H.).

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Booth P.J., Curran A.R. Membrane protein folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1999;9:115–121. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)80015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cramer W.A., Engelman D.M., Rees D.C. Forces involved in the assembly and stabilization of membrane proteins. FASEB J. 1992;6:3397–3402. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.15.1464373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackenzie K.R. Folding and stability of alpha-helical integral membrane proteins. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:1931–1977. doi: 10.1021/cr0404388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleinschmidt J.H. Membrane protein folding on the example of outer membrane protein A of Escherichia coli. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2003;60:1547–1558. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3170-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleinschmidt J.H. Folding kinetics of the outer membrane proteins OmpA and FomA into phospholipid bilayers. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2006;141:30–47. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamm L.K., Hong H., Liang B. Folding and assembly of β-barrel membrane proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1666:250–263. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel G.J., Behrens-Kneip S., Kleinschmidt J.H. The periplasmic chaperone Skp facilitates targeting, insertion, and folding of OmpA into lipid membranes with a negative membrane surface potential. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10235–10245. doi: 10.1021/bi901403c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pocanschi C.L., Patel G.J., Kleinschmidt J.H. Curvature elasticity and refolding of OmpA in large unilamellar vesicles. Biophys. J. 2006;91:L75–L77. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.091439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surrey T., Jähnig F. Refolding and oriented insertion of a membrane protein into a lipid bilayer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:7457–7461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Surrey T., Jähnig F. Kinetics of folding and membrane insertion of a β-barrel membrane protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:28199–28203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.47.28199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleinschmidt J.H., Tamm L.K. Folding intermediates of a β-barrel membrane protein. Kinetic evidence for a multi-step membrane insertion mechanism. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12993–13000. doi: 10.1021/bi961478b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleinschmidt J.H., Tamm L.K. Secondary and tertiary structure formation of the β-barrel membrane protein OmpA is synchronized and depends on membrane thickness. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;324:319–330. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong H., Joh N.H., Tamm L.K. Methods for measuring the thermodynamic stability of membrane proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2009;455:213–236. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong H., Park S., Tamm L.K. Role of aromatic side chains in the folding and thermodynamic stability of integral membrane proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:8320–8327. doi: 10.1021/ja068849o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong H., Tamm L.K. Elastic coupling of integral membrane protein stability to lipid bilayer forces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:4065–4070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400358101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stanley A.M., Fleming K.G. The process of folding proteins into membranes: challenges and progress. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008;469:46–66. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Surrey T., Schmid A., Jähnig F. Folding and membrane insertion of the trimeric β-barrel protein OmpF. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2283–2288. doi: 10.1021/bi951216u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahalakshmi R., Franzin C.M., Marassi F.M. NMR structural studies of the bacterial outer membrane protein OmpX in oriented lipid bilayer membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:3216–3224. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shanmugavadivu B., Apell H.-J., Kleinschmidt J.H. Correct folding of the β-barrel of the human membrane protein VDAC requires a lipid bilayer. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;368:66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pocanschi C.L., Apell H.-J., Kleinschmidt J.H. The major outer membrane protein of Fusobacterium nucleatum (FomA) folds and inserts into lipid bilayers via parallel folding pathways. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;355:548–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huysmans G.H.M., Radford S.E., Baldwin S.A. The N-terminal helix is a post-assembly clamp in the bacterial outer membrane protein PagP. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;373:529–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burgess N.K., Dao T.P., Fleming K.G. β-barrel proteins that reside in the Escherichia coli outer membrane in vivo demonstrate varied folding behavior in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:26748–26758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802754200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kong H.J., Mooney D.J. Microenvironmental regulation of biomacromolecular therapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:455–463. doi: 10.1038/nrd2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torchilin V.P. Recent advances with liposomes as pharmaceutical carriers. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:145–160. doi: 10.1038/nrd1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleinschmidt J.H., den Blaauwen T., Tamm L.K. Outer membrane protein A of Escherichia coli inserts and folds into lipid bilayers by a concerted mechanism. Biochemistry. 1999;38:5006–5016. doi: 10.1021/bi982465w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleinschmidt J.H., Tamm L.K. Time-resolved distance determination by tryptophan fluorescence quenching: probing intermediates in membrane protein folding. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4996–5005. doi: 10.1021/bi9824644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ebie Tan A., Burgess N.K., Fleming K.G. Self-association of unfolded outer membrane proteins. Macromol. Biosci. 2010;10:763–767. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200900479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rasband, W. ImageJ. 1997–2009. U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland. http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/.

- 29.Senff L.M., Wegener W.S., Makula R.A. Phospholipid composition and phospholipase A activity of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 1976;127:874–880. doi: 10.1128/jb.127.2.874-880.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleinschmidt J.H., Tamm L.K. Structural transitions in short-chain lipid assemblies studied by 31P-NMR spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2002;83:994–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75225-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petrache H.I., Dodd S.W., Brown M.F. Area per lipid and acyl length distributions in fluid phosphatidylcholines determined by 2H NMR spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2000;79:3172–3192. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76551-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dill K.A., Flory P.J. Interphases of chain molecules: monolayers and lipid bilayer membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:3115–3119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alves M., Peric M. An EPR study of the interfacial properties of phosphatidylcholine vesicles with different lipid chain lengths. Biophys. Chem. 2006;122:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grit M., Crommelin D.J. Chemical stability of liposomes: implications for their physical stability. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1993;64:3–18. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(93)90053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho R.J.Y., Schmetz M., Deamer D.W. Nonenzymatic hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine prepared as liposomes and mixed micelles. Lipids. 1987;22:156–158. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cafiso D.S. Influence of charges and dipoles on macromolecular adsorption and permeability. In: Disalvo E.A., Simon S.A., editors. Permeability and Stability of Lipid Bilayers. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1995. pp. 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Y., Mayer K.M., Hafner J.H. Probing the lipid membrane dipole potential by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 2008;95:5193–5199. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.136507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brockman H. Dipole potential of lipid membranes. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1994;73:57–79. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(94)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clarke R.J. The dipole potential of phospholipid membranes and methods for its detection. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2001;89-90:263–281. doi: 10.1016/s0001-8686(00)00061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray D., Honig B. Electrostatic control of the membrane targeting of C2 domains. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:145–154. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00426-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tendian S.W., Lentz B.R. Evaluation of membrane phase behavior as a tool to detect extrinsic protein-induced domain formation: binding of prothrombin to phosphatidylserine/phosphatidylcholine vesicles. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6720–6729. doi: 10.1021/bi00480a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seelig A., Seelig J. Effect of a single cis double bond on the structures of a phospholipid bilayer. Biochemistry. 1977;16:45–50. doi: 10.1021/bi00620a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silvius J.R. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1982. Thermotropic Phase Transitions of Pure Lipids in Model Membranes and Their Modifications by Membrane Proteins. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clarke R.J. Effect of lipid structure on the dipole potential of phosphatidylcholine bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1327:269–278. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(97)00075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lakowicz J.R. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Springer; New York: 2006. Protein fluorescence; pp. 530–573. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.