Abstract

Robust circadian oscillations of the proteins PERIOD (PER) and TIMELESS (TIM) are hallmarks of a functional clock in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Early morning phosphorylation of PER by the kinase Doubletime (DBT) and subsequent PER turnover is an essential step in the functioning of the Drosophila circadian clock. Here using time-lapse fluorescence microscopy we study PER stability in the presence of DBT and its short, long, arrhythmic, and inactive mutants in S2 cells. We observe robust PER degradation in a DBT allele-specific manner. With the exception of doubletime-short (DBTS), all mutants produce differential PER degradation profiles that show direct correspondence with their respective Drosophila behavioral phenotypes. The kinetics of PER degradation with DBTS in cell culture resembles that with wild-type DBT and posits that, in flies DBTS likely does not modulate the clock by simply affecting PER degradation kinetics. For all the other tested DBT alleles, the study provides a simple model in which the changes in Drosophila behavioral rhythms can be explained solely by changes in the rate of PER degradation.

Keywords: Drosophila, Protein Degradation, Protein Kinases, Protein Phosphorylation, Protein Stability, CK1, Doubletime, Period Protein, Circadian Rhythms, Cultured Cells

Introduction

During a 24-h cycle, levels of PERIOD (PER)2 and TIMELESS (TIM) proteins peak in the late night and begin to diminish thereafter. Genetic and biochemical studies suggest that the kinase Doubletime (DBT), an ortholog of the vertebrate casein kinase 1ϵ, modulates phosphorylation and the early morning degradation of PER in core clock neurons (1–4). Degradation of PER occurs through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, where the DBT-phosphorylated PER binds the F-box protein SLIMB and is targeted for degradation (5–7). In vivo, DBT physically interacts with PER and is found to be associated with the PER-TIM complex (8) with TIM stabilizing PER by suppressing PER phosphorylation (1, 6).

Several mutations of the dbt locus have been isolated and the short-period (dbtS) and the long-period (dbtL) alleles are among the best characterized dbt mutants in the literature (1–3, 6, 9). dbtL is a Met-80 → Ile mutation that causes period lengthening of PER and TIM oscillations and animal behavioral activity, to ∼27 h. Alterations in PER cyclic profile suggest that the DBTL mutation extends the animal rhythms by reducing the rate of PER phosphorylation. Indeed, in vitro gel shift and phosphorylation experiments indicate DBTL has decreased kinase activity compared with DBT (6, 9, 10), which would likely lead to slower degradation of PER in clock neurons. However, the predicted reduction in PER turnover rate due to the long-mutation on DBT has not been tested. dbtS has a Pro-47 → Ser mutation that results in shortened PER and TIM oscillation period and fly locomotor activity interval of ∼18–20 h. From in vivo studies there is no conclusive evidence as to the mechanism via which the mutation affects period length. In vitro, some studies show a ∼10% decrease in kinase activity for DBTS when compared with DBT (9, 10), suggesting that the mutant is a hypomorph. In cell culture, gel shift assays report hyperphosphorylation of PER (6, 11) in the presence of DBTS implying that the mutant is a hypermorph. Owing to the lack of detailed data, no clear mechanistic link has been established between the mutation and the shortening of period.

Another variant of the kinase is doubletime arrhythmic (dbtar), which is a hypomorphic allele with a His-126 → Tyr mutation (3). Homozygous dbtar flies are viable but arrhythmic, while heterozygous dbtar/+ animals show a long ∼29 h activity rhythm. At the protein level, Western blot analysis of Drosophila brain extracts shows constitutively high levels of PER across circadian time, composed of hypo and hyperphosphorylated fractions of the protein (3, 12). Cell culture experiments have also shown that DBTar has substantially reduced kinase activity, lowest of all catalytically active alleles of DBT (10). Lastly, the DBT protein carrying the Lys-38 → Arg mutation in its ATP binding site is catalytically inactive, although its ability to bind PER remains unaltered (13). This mutant, DBTK38R, diminishes PER phosphorylation and oscillation in the fly brain and produces behavioral rhythms with period >30 h in hemizygous animals (12, 13). Similar to the short and long-period mutants, kinetics of PER stability has not been thoroughly examined in the presence of DBTar or DBTK38R.

DBT is expressed in Drosophila embryonic Schneider 2 (S2) cells, but at levels that do not produce detectable phosphorylation of exogenous PER by gel shift (6, 14). However, overexpression of the kinase in these cells using a constitutive promoter has been shown to qualitatively recapitulate phosphorylation pattern of overexpressed PER (6, 9). The PER phosphorylation experiments were done on cell ensembles, which expressed proteins with slowly activated promoters over several hours or even days. Additionally, the studies did not report on protein localization, degradation, or on substrate-kinase interaction kinetics. More recent in vitro experiments using fluorescently labeled clock proteins in individual S2 cells demonstrated that a substantial fraction of DBT localize to the nucleus when overexpressed alone or with TIM (15), consistent with in vivo studies that indicate nuclear localization of DBT in per01 and per0 fly heads (8, 16). However, when coexpressed with PER, the study showed that DBT is mostly cytoplasmic and the PER-DBT interaction can lead to gradual turnover of PER (15). This preliminary PER-DBT study established that the proteins interact in S2 cells but it did not fully explore the kinetics of the ensuing degradation process. Consequently, critical details of PER turnover in the presence of DBT remain poorly understood. Importantly, although a number of DBT mutations have been described in the literature, a single model that provides a molecular explanation for behavioral alterations by these mutations is still missing.

To devise such a model, we investigated the kinetics of PER turnover by coexpressing different alleles of DBT in S2 cells. We employed time-lapse microscopy and followed spatial and temporal trajectories of PER and DBT in S2 cells for several hours immediately after induction. The data show robust PER turnover in the presence of overexpressed DBT, with the half-life of degradation ranging between 1.2 and 6.5 h and the fraction of undegraded substrate ranging between 10–100%, both depending strongly on the DBT allele that is coexpressed with PER. In contrast, the onset of PER turnover appears to be more tightly regulated with protein abundance starting to diminish typically within 3–5 h after induction, regardless of the form of DBT that is coexpressed. We find a surprisingly close association between PER half-lives measured in cultured cells and the corresponding animal behavioral rhythms modulated by mutations in dbt. Among the tested variants of the kinase, DBTS is the only one that does not follow this close correlation. Our model connecting fly rhythms to PER half-life implies that the DBTS mutant likely does not alter behavioral period through a simple alteration of PER stability.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning

yfp, cfp, and mCherry with EcoRI and NotI ends were generated by PCR from pd2EYFP (Clontech), pdECFP (Clontech), and pRSET-B mCherrry (Roger Tsien laboratory), respectively, with primers CGAATTCGAGGAGGCatggtgagcaagggcgag and TGCGGCCGCttacttgtacagctcgtccatgcc and cloned into digested plasmid pd2EYFP. The NheI-NotI region of the modified construct was next cloned into a pCasper-hs plasmid carrying the Drosophila hsp70 promoter (17) with the EcoRI site replaced by NheI. Each variant of dbt was individually amplified with the primers CGCTAGCatggagctgcgcgtgggtaaca and GCGAGATCTGAtttggcgttccccacgccac and subsequently cloned between NheI and BglII of pCasper-hs carrying the desired fluorescent gene. The KpnI and NotI sites in pCasper-hs carrying per-cfp as described in Ref. 18 were used to replace cfp with other fluorescent tags as necessary. The following primers were used to carry out the cloning: GCGGTACCAGGAGGCatggtgagcaagggcgag and TGCGGCCGCttacttgtacagctcgtccatgcc. TIM-YFP was constructed as described in Ref. 18.

Transfection

S2 cells were grown in Schneider's Drosophila medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 15% FBS (Sigma). Cells were transfected with 100–200 ng of hsper-tag1, 50–100 ng of hsdbt-tag2, 10–20 ng of hs-tag3, and empty pCasper-hs totaling 400 ng of DNA in 6-well plates using the Effectene Transfection Reagent (Qiagen). After 12–18 h of incubation, the cells were washed once in PBS and resuspended in fresh medium. Tags 1, 2, and 3 varied among CFP, YFP, and mCherry.

Fluorescence Microscopy

36–48 h post-transfection, cells were moved to a Lab-Tek II coverglass chamber (Nunc), heat-shocked at 37 °C for 30 min and after 5–10 min of recovery, cell growth medium was replaced with Hanks' balanced salt solution (Invitrogen) for microscopy at room temperature. For imaging, we used a DeltaVision system (Applied Precision) equipped with (i) an inverted Olympus IX70 microscope carrying a 60× oil objective, 1.42 N.A., (ii) CFP/YFP/mCherry filter set and dichroic mirror (Chroma), (iii) a CCD camera (Photometrics), and (iv) an XYZ piezoelectric stage for locating and revisiting multiple cells over several hours. Time lapse images, with appropriate filter sets for each fluorescent channel, were captured every 5–10 min and repeated for 6–12 h. For each image, cells were exposed to excitation signal for 0.1–0.3 s. The short excitation time ensured long survival time for majority of cells, although multiple phototoxicity-related cell deaths were observed.

Image Segmentation

Images were saved in 16-bit *.dv format and interpreted by custom-written software in Matlab (Mathworks Inc.). Briefly, individual cells were automatically segmented in the control (CFP only, YFP only, or mCherrry only) channel by detecting the edge between background and fluorescent objects, yielding cell periphery. Nucleus was detected by identifying area within a cell with signal 20% higher than the average of the entire cell. Two binary masks, one for the whole cell and one for the nucleus, were generated for each cell at each time point and applied to all channels at that time point. Total fluorescence for a cell in each channel (example, supplemental Fig. S2) was calculated by multiplying the “whole-cell mask” by the original image in that channel and subtracting the background signal in that channel. The average fluorescence (example, Fig. 1, B–D) was determined by dividing the total fluorescence by the number of “on” (=1) pixels of the mask. Total and average signals from the nucleus were calculated similarly. Cytoplasmic fluorescence was set equal to the difference between whole-cell and nucleus signals.

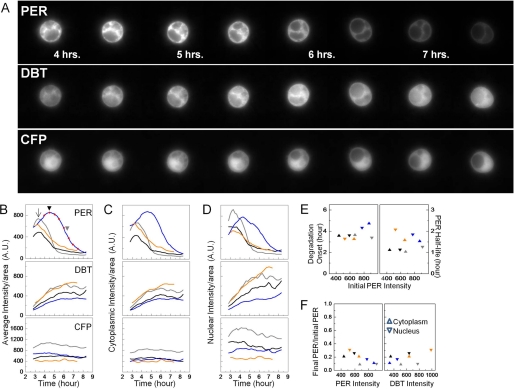

FIGURE 1.

DBT produces rapid PER turnover in S2 cells. PER-YFP, DBT-mCherry, and CFP (control) were induced by heat-shock at 37 °C for 30 min (time = 0 h). The spatio-temporal distribution of each protein was then monitored over several hours post heat-shock. A, selected snapshots of the three fluorescent channels in an S2 cell at a half-hour interval starting at 4 h post heat-shock. PER-YFP gradually accumulates and then starts to drop off after 4.5 h. During that time, DBT-mCherry level rises at a decreasing rate (middle panel) while CFP abundance remains steady (bottom panel). B–D, quantification of the entire time-lapse movie for four individual cells representing a varied population with each represented in a different color. Blue line corresponds to the cell in A with red dots (B, top panel) indicating the time points for the selected images. The fluorescence signal in B is an average of the cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (D) signals per unit area for each cell. E, time for the onset (left y axis) and the half-life (right y axis) of PER degradation in each of the four cells in B–D. The color of the symbol corresponds to the color of line in B–D. F, fraction of PER remaining after completion of degradation in the four cells. The residual cytoplasmic and nuclear PER levels are plotted against substrate and kinase abundance.

Analysis of Fig. 4

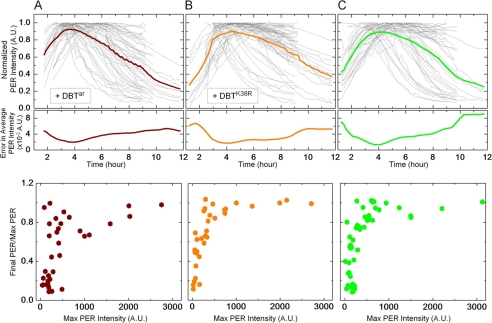

FIGURE 4.

Compared with the other alleles, DBTar and DBTK38R extend the half-life of PER. Normalized PER-YFP levels in individual cells (top panel, thin gray line) co-expressing (A) DBTar (n = 56 cells), (B) DBTK38R (n = 62 cells), or (C) no exogenous DBT (n = 53 cells). In each instance, the average PER intensity versus time and its standard error are shown in thick lines, top and middle panels, respectively. The measurements show PER has a half-life of about 5.4 h and 6.5 h in the presence of DBTar and DBTK38R, respectively, and 5.1 h with endogenous DBT. PER half-lives with DBTar and DBTK38R are both severalfold longer than with DBT, DBTS, or DBTL. Unlike in Figs. 2C and 3C, the fraction of left-over PER after interaction with these DBT alleles is found to depend strongly on the initial accumulation of the protein in the cell (bottom panels). In all three cases, cells expressing large amounts of PER show stable levels of the protein even ∼10 h after induction.

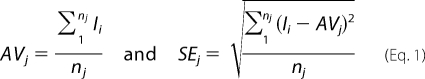

PER profile versus time from each cell was first divided by its maximum intensity so that the scaled fluorescence values ranged between 0 and 1 (gray lines in upper panels). Next, the average value (thick lines in upper panels), AVj, at each time point t = j was calculated by summing all the scaled intensities at j and by dividing by the total number of cells that have datum at j. This approach of determining the average PER profile gives equal weight to each cell data regardless of protein expression level and without skewing the results toward either the high or the low PER expressing cells. Information on any dependence of PER stability on its own expression levels are also retained and are shown in the bottom panel of the figure. The error curve (middle panels) is calculated by computing the standard deviation (S.D.) in fluorescence at t = j and then dividing the S.D. by the square root of the total number of cells considered at that time point. In short, with nj as the total number of cells at t = j and Ii as the scaled intensity of the i-th cell (i = 1,2,… nj) at j, the two quantities are defined as in Equation 1.

|

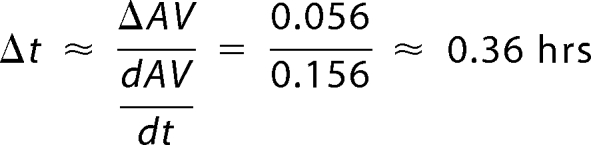

Error on the half-life of PER, Δt, is computed using the approximation ΔAV/Δt∼dAV/dt, where dAV/dt is the derivative of the average PER intensity with respect to time calculated for the time at which the average PER value reaches half its maximum level. ΔAV is the error in the average value of PER level at the half-life time (Fig. 4, A–C, middle panel). For example, for the last panel in the Fig. we have peak value of AV at t = 4.18 h and AV/2 at t = 9.22 h giving a half-life of 5.04 h; ΔAV = S.E. (at t = 9.22 h) = 0.056; dAV/dt (at t = 9.22 h) = 0.156/h. Therefore, we have:

|

Analysis of Fig. 5 and Supplemental Table S1

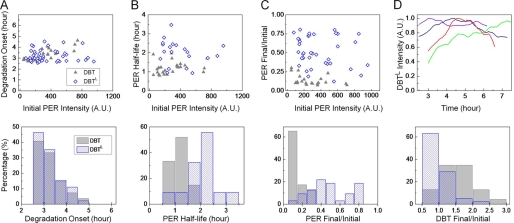

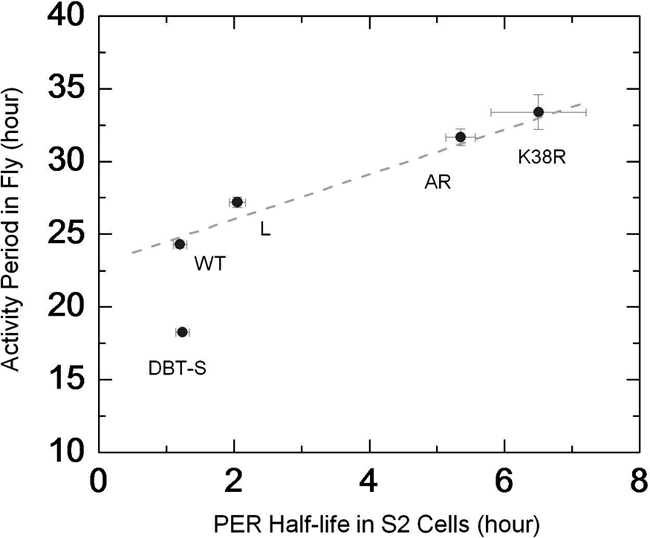

FIGURE 5.

Variations in fly behavioral period can be linked to PER half-life in S2 cells. Period of behavioral rhythms in wild-type and DBT-mutant animals compared with the half-life of PER as measured in S2 cells coexpressing the kinase alleles. Except for the dbtS mutation, the comparison reveals a simple relationship between regulation of fly activity and PER stability in cultured cells for the different variants of DBT. The dashed line is only a visual guide and not a fit to the data.

Fly data for the figure were gathered from Refs. 3, 4, 13 and shown in the table. Much of the data are from Ref. 13 where the authors generated a series of animals all expressing one copy of a particular allele of dbt using the tim-Gal4 or tim-UAS-Gal4 driver and UAS-DBT allele insertion in a wild-type background. For example, genotype of the first DBTS line in the Table is tim-Gal4/+>UAS- DBTS/+, which gave a period of 18.4 ± 0.1 h with 74% rhythmic flies among tested progenies (13). We considered these lines since they expressed different transgenes using similar method and in a background of wild-type DBT, comparable to the situation in our S2 cells where variants were overexpressed over endogenous wild-type DBT.

In calculating the average period length, we weighted each genotype with the fraction of rhythmic flies in that line. For instance, for DBTS average period = (18.4 × 0.74 + 18.4 × 0.47 + 18.2 × 0.5 + 18.0 × 0.65)/(0.74 + 0.47 + 0.5 + 0.65) h = 18.2 h. Similarly, the error on the average period was calculated as:

This method of weighing with the percentage of rhythmic animals ensures that estimated values are representative of the genotype and not biased by outliers. The rule was applied to all genotypes in the study. In one case (DBTK38R), the first line was left out of the analysis because the authors of Ref. (13) point out an anomalous period length caused by low expression of the transgene in those animals.

Immunoprecipitation

Cells co-transfected with actin promoter driving per-V5 and dbt variant-myc (pAc-per-V5, pAc-dbt-myc) were lysed 48 h post-transfection with ∼200 μl of modified RIPA buffer. A sample for input lysate was separated, and the remaining extracts were incubated overnight at 4 °C with 1:100 anti-V5 antibody (Sigma). Immune complexes were collected with Gammabind G Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) and washed three times with RIPA. The immunoprecipitate and input were analyzed by immunoblot using a 6% SDS-PAGE gel, and probed with anti-V5 (1:10,000 dilution) or anti-MYC (Sigma, 1:7000 dilution).

RESULTS

PER Is Destabilized by DBT within a Few Hours of Expression in Cultured Cells

To quantify PER degradation and to tease out the effects of DBT mutations on the process, we formulated a testable hypothesis based on three ad hoc parameters (supplemental Fig. S1). These parameters are the (i) onset of PER degradation, measured from the time of protein induction, (ii) PER half-life, which is the time it takes from the start of degradation for the substrate to reach half of its maximum level, and (iii) ratio of PER remaining after degradation process has ended to the level of PER at the onset of degradation. Our initial hypothesis involves the best studied alleles DBT, DBTS, and DBTL and argues that the shortening of fly rhythm from dbtL to dbtS can be explained in terms of (a) earlier onset of PER turnover (supplemental Fig. S1, left panel), (b) shorter half-life of PER (middle panel), or (c) higher fraction of PER that is degraded in the process (right panel).

First, we monitored spatio-temporal changes of fluorescently tagged PER and wild-type DBT molecules. 27 cells were examined and four randomly selected cells from this heterogeneous population are shown in Fig. 1. The cells were co-transfected with PER fused to yellow fluorescent protein behind a heat-shock promoter (hs-per-yfp), hs-dbt-mcherry, and hs-cfp. The function of the CFP-only channel is 2-fold. First, steady signal of the non-clock protein serves as an internal control in individual cells for assessing the stability of the coexpressed clock proteins and overall cell viability. Second, the CFP signal functions as a nuclear marker and permits subcellular analysis of the exogenous protein levels.

Within an hour of induction by heat-shock at 37 °C, the cells rapidly express proteins at detectable levels in three spectrally distinct fluorescent channels. In one example, PER-YFP abundance (Fig. 1A and blue line in B–D) slowly increases in all cellular compartments for several hours after induction. Shown here are the protein levels per unit area, and as a result of this normalization the cytoplasmic and nuclear levels appear comparable (panels C and D). In terms of total protein abundance, however, there is 4-fold more PER in the cytoplasm relative to the nucleus (supplemental Fig. S2). At ∼4.5 h, PER levels start to diminish rapidly (Fig. 1B, black arrowhead) and reach half its peak value within less than 2 h (gray arrowhead). The fast destabilization of PER in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus occurs simultaneously with increasing DBT levels (middle panels, Fig. 1, A–D) and independently of its fluorescent tag (see “Experimental Procedures”). Unlike PER, DBT remains relatively stable after reaching maximum value 6 h post-induction. Without exogenous DBT, PER is much more stable (supplemental Fig. S3; discussed below). The control CFP-only channel (bottom panels, A–D) shows a steady fluorescent signal, which is predominantly nuclear during the entire course of the experiment. Qualitatively similar observations are made in other cells co-expressing PER and DBT (n = 27). Three more cells from this population are also shown here to highlight cell-cell heterogeneity (Fig. 1, B–D, gray, black, and orange lines). Our single cell assay faithfully captures the variations in the timing of PER degradation (panel B, contrast black arrow and black arrowhead), rate of PER turnover and protein expression levels that exist in large S2 cell ensembles.

The time-lapse microscopy data from the four PER+DBT cells are summarized in Fig. 1, E and F. The onset of PER degradation is observed 3–5 h after protein induction (Fig. 1E, left panel) with an average degradation half-life of about 1.5 h (Fig. 1E, right panel), and these degradation parameters are found to be independent of both the pre-degradation PER level and its subcellular distribution. Additionally, the fraction of PER remaining after end of degradation is found to range between 0.09 and 0.3 in both cellular compartments and with no systematic dependence on either the initial PER level (Fig. 1F, left panel) or DBT abundance (Fig. 1F, right panel). Because the degradation kinetics appear to be statistically independent of PER subcellular location, from here on we will refer to the whole-cell average when discussing protein turnover.

When TIM is coexpressed with PER and DBT, only the fraction of cytoplasmic PER unbound to TIM is degraded (data not shown). PER turnover in the cytoplasm is followed by nuclear entry of the three proteins within 8 h after coinduction (supplemental Fig. S4A), with nuclear entry occurring ∼5.5 h postinduction, on average. The average onset of PER/TIM/DBT nuclear entry is similar to that of PER/TIM, as measured previously in S2 cells (18). The previous PER-TIM experiments also reported that onset of PER and TIM nuclear entries is not always simultaneous. To determine the order of nuclear translocations of the three proteins PER/TIM/DBT in our experiments, we next compare timing of TIM and DBT nuclear translocation to that of PER (supplemental Fig. S4B). We find that in most cases, DBT enters the nucleus alone and before PER and TIM, presumably after PER degradation is underway (supplemental Fig. S3B; red symbols below dashed line). In vivo brain staining images at 4 h intervals by Kloss et al. (2) suggested that PER and DBT move to the nucleus simultaneously. Our higher resolution cell culture studies instead imply that the substrate and kinase likely enter the nucleus separately (∼1–2 h apart). Moreover, in about half of the cells examined, PER and TIM entered the nucleus simultaneously (black symbols on dashed line), while in the rest the two proteins moved independently into the nucleus, similar to previous findings in cell culture (18). The protein translocation data, therefore, indicate that DBT may enter the nucleus separately from PER and overexpression of the kinase in S2 cells does not significantly alter the average timing of nuclear entry of the PER/TIM complex.

Our time-lapse fluorescence experiments reveal rapid, robust PER turnover when coexpressed with wild-type DBT in the S2 cell culture system. The data suggest that the interaction with DBT leads to PER degradation typically starting within 3.5 h of protein induction, with a half-life of 1.5 h, and with an eventual 10-fold reduction in cytoplasmic and nuclear PER. The presence of TIM diminishes the effect of DBT on PER by protecting a large subset of cytoplasmic PER from degradation and allowing PER/TIM/DBT transport into the nucleus. Qualitatively, these results resemble several in vivo observations (1, 8, 20, 21) and provide additional quantitative insights into interactions among Drosophila PER, TIM, and DBT.

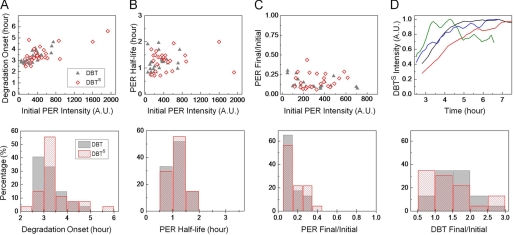

DBT Short Mutation Does Not Change PER Degradation Kinetics

Next, we assessed the effect of the short-period mutant of DBT on PER degradation in the S2 cells. Fluorescently labeled PER and DBTS were coexpressed to monitor protein stability in individual cells over several hours following induction. The time-lapse recordings, similar to Fig. 1A, were analyzed to extract kinetic parameters defined earlier: onset of PER degradation, half-life of PER, and the fraction of protein remaining after completion of the degradation process. The single-cell data indicate that initiation of PER degradation occurs around 3.4 ± 0.1 h (mean ± S.E.) when DBT (n = 27 cells) is overexpressed, and this remains largely unchanged if instead DBTS is coexpressed with PER (3.4 ± 0.13 h, n = 28). The binned distribution (bin size = 30 mins) of the onset times is, however, different for the two DBT alleles (Fig. 2A, bottom panel). Roughly 40% of DBT expressing cells begin to show PER turnover within <3 h of induction while it takes >3 h for the equivalent fraction of DBTS cells to show similar behavior. Once it commences, PER degradation proceeds rapidly in the presence of either forms of DBT. We find the degradation half-life to be 1.20 ± 0.1 h with DBT and 1.24 ± 0.1 h with DBTS (Fig. 2B). The measured PER half-life in the S2 cells is quite comparable to that estimated from Western blot analysis of fly heads, which suggests a peak-trough transition time of ∼2 h both in dbts and dbt flies (1). The fraction of PER remaining after the conclusion of degradation may be used as a measure of the efficacy of the kinase activity. This quantity, PER Final/PER Initial, is plotted against the peak protein abundance immediately before degradation is initiated (Fig. 2C). The data indicate that presence of excess DBT, on average, diminishes PER abundance to 0.14 ± 0.07 of its initial level with only a modest change when DBTS (0.17 ± 0.1) replaces DBT (p = 0.13, Wilcoxon test). Finally, we examine DBTS expression in S2 cells (example traces in upper row, panel D) and find that on average the mutant is as stable as the wild-type allele (bottom row, panel D). Thus, on the merit of the examined parameters, kinetics of PER turnover are indistinguishable in the presence of DBT or DBTS.

FIGURE 2.

PER degradation kinetics remain unaltered by the DBTS mutation. A, timing of the onset of PER degradation in cells co-expressing exogenous DBT (gray, n = 27 cells) or DBTS (red, n = 28 cells). With DBT, the PER level starts to decrease around 3.4 ± 0.1 h and with DBTS around 3.4 ± 0.13 h. B, interaction with DBT confers a half-life of 1.20 ± 0.1 h on PER, independent of pre-degradation PER levels. With DBTS, average PER half-life in S2 cells is 1.24 ± 0.1 h. C, on average, DBT reduces PER to 0.14 ± 0.07 of its pre-degradation levels whereas for DBTS the fractional drop in PER is 0.17 ± 0.1. The fraction of PER-YFP remaining after degradation is also independent of the initial PER abundance. D, examples of DBTS temporal variation when co-expressed with PER. DBTS stability is similar to that of DBT (lower panel).

DBT Long Prolongs PER Turnover in Cell Culture

We conducted similar experiments with DBTL and find that PER turnover starts around 3.19 ± 0.07 h (Fig. 3A, n = 50) in the presence of this mutant kinase and statistically indistinguishable from when the wild-type allele is expressed. However, despite the similar times of onset, PER degradation progresses at a slower rate in the presence of the long-period mutant. The average half-life of PER is 2.05 ± 0.12 h in the presence of DBTL, significantly longer than that with DBT, ∼1.2 h (p < 10−5, Wilcoxon test). The longer PER half-life in DBTL cells is also apparent in a comparison of the half-life measurements of the two cell populations (Fig. 3B, bottom row) and appears to mimic the slower rate of PER turnover in head extracts of dbtL flies (1). In terms of fractional change in PER abundance because of the kinase activity, we again find a notably large difference between DBTL and DBT cells (p < 10−5). In cells expressing DBTL, ∼52% of PER remains undegraded on average (Fig. 3C), whereas with DBT or DBTS, PER loss is robust with typically only ∼10% of residual PER at the end of the degradation process (Fig. 2C). To determine whether kinase stability affects PER degradation kinetics, we looked at variations of DBTL levels over time (Fig. 3D). Compared with DBT, DBTL appears slightly less stable (Fig. 3D, bottom row; p < 10−3) although no significant association is found between the half-life of PER and the fractional change in DBTL level in individual cells (data not shown). In fact, additional experiments with cycloheximide show a reduced half-life for the long-period mutant compared with DBT (∼30 min reduction with 25 μg/ml of cycloheximide; data not shown). Thus, compared with wild-type DBT, DBTL is less stable and its overexpression in cell culture produces both a slower rate of PER turnover and a less efficient degradation of the substrate. The longer activity period in the dbtL mutants is likely a consequence of these changes in PER degradation kinetics.

FIGURE 3.

DBTL mutation results in slower PER turnover. A, onset of PER degradation in cells co-expressing DBTL is around 3.19 ± 0.07 h (blue, n = 50 cells). The onset does not depend on the initial PER level. B, half-life of PER is independent of pre-degradation abundance and on average longer because of the DBTL mutation. With the wild-type DBT allele, PER has a half-life of 1.20 ± 0.1 h and with DBTL the turnover is slower with a half-life of 2.05 ± 0.12 h. Plotted here are only those DBTL cells where PER levels dropped to ≤0.5 of their pre-degradation value. C, DBTL mutation also leads to degradation of a smaller fraction of the available PER. While DBT destabilizes PER levels to ∼10%, DBTL activity degrades only ∼52% (0.52 ± 0.05) of PER molecules. D, long-period mutation renders DBT slightly unstable.

Overexpression of DBTar or DBTK38R Extends the Half-life of PER

Previous in vitro experiments indicate that the kinase activity of the mutant dbtar is severely compromised (10), and predict a relatively stable PER in S2 cells. Similar predictions are made for the catalytically inactive allele dbtK38R (13). We sought to measure the average half-life of PER in the presence of DBTar and compare it to that with the inactive mutant DBTK38R. We also measured PER half-life with no ectopic expression of DBT in S2 cells and examine results from these three groups in Fig. 4.

Initial studies showed large cell-cell variations in PER temporal changes when coexpressed with DBTar. The heterogeneity was much larger than in the case of DBT, DBTS, or DBTL where each cell could be analyzed individually and a PER half-life determined in most cells. With DBTar some cells showed very stable PER, not yielding a measurable half-life, while others yielded half-life <2 h similar to that obtained with DBT. To incorporate all the heterogeneity in the analysis and still maintain the single-cell nature of the measurements, we analyzed DBTar cells by normalizing PER temporal profile of each cell by its maximum fluorescence (Fig. 4A, thin gray lines) and calculating the entire population average and standard error at each time point (Fig. 4A, thick color lines, top, and middle panels). The average PER profile in DBTar cells shows increasing PER for post-induction time t < 4 h and a slowly decreasing protein level in the population for t > 4 h. On average, we find that PER diminishes with a half-life of 5.35 ± 0.22 h in DBTar-expressing cells. By comparison, and following similar analysis, cells expressing DBTK38R on average show a more gradual PER turnover with a longer half-life of 6.5 ± 0.7 h (Fig. 4B, top panel).

A number of previous studies on PER stability in S2 cells have concluded that endogenous DBT, though found at detectable levels (14), is insufficient to destabilize overexpressed PER (6, 13, 22). At odds with these data, our single-cell experiments show that PER stability is indeed affected without ectopic DBT expression (Fig. 4C, top panel). When followed from the time of induction up to 12 h, a considerable fraction of S2 cells shows PER degradation starting around 4.8 h and with an average half-life of 5.05 ± 0.36 h. This half-life is comparable to that in DBTarcells but shorter than the measured half-life in DBTK38R cells. Our result that wild-type DBT is recessive to DBTK38R, is consistent with the dominant negative function of DBTK38R already demonstrated in flies (13). To verify that the increase in PER stability was not due to unstable kinases, we measured temporal profiles of DBTar and DBTK38R, which indicate no significant changes in stability of the mutants compared with the wild-type allele (data not shown).

In addition to the cells that display unstable PER, a large number of cells with no exogenous DBT, with DBTK38R or with DBTar, show relatively stable levels of the protein. In fact, temporal changes of PER level in these three groups (+DBTar, +DBTK38R, and no ectopic DBT) depend strongly on PER cellular accumulation prior to onset of degradation (Fig. 4, A–C, bottom panels). Cells expressing high amounts of PER within 3–4 h of induction show steady protein levels up to ∼10 h whereas those with low abundance show substantial drop in PER levels. In contrast, no such dependence on substrate concentration is apparent in DBT, DBTS, or DBTL cells (Figs. 2 and 3, panel C), and the data indicate that PER accumulation is not allowed to reach very high levels when these more active kinases are present in abundance.

PER stability at high concentrations cannot be explained simply in terms of the substrate turnover being rate limited by low kinase activity. This scenario would predict a progressive delay in the onset of degradation with increase in substrate abundance in each of the three cell types, a behavior not supported by data (supplemental Fig. S5). Altered physical interactions between the substrate and the kinase cannot explain the DBTar/DBTK38R/endogenous-only cell results either, because no significant binding differences sufficient to explain Fig. 4 data are seen between PER and the tested variants of DBT (supplemental Fig. S6). Instead, the observed dependence of PER stability on its own abundance in these cells may be due to a change in intermolecular kinetics tuned by the ratio of substrate concentration to active kinase concentration. At low PER level (PER < 300 A.U.), there is sufficient diffusional encounter between PER and basal levels of endogenous but active kinase, leading to rapid PER degradation. In cells with high concentration of PER (PER > 500 A.U.), encounters among PER molecules becomes more likely than that between PER and endogenous DBT. This switch in intermolecular kinetics likely favors the formation of PER:PER homodimers (23, 24). Accumulation of PER aggregates or PER-PP2A phosphatase binding (25) is also possible but less likely. However, any one of these three scenarios would result in more stable forms of the substrate. The overexpression of DBTar or DBTK38R does not markedly alter this “Hill-function” type behavior (compare Fig. 4A and 4B with 4C) because even frequent binding between the enzymatically compromised mutants and PER cannot significantly reduce substrate stability.

DISCUSSION

Our studies following the temporal pattern of fluorescently labeled PER and DBT indicate that the onset of PER degradation is very tightly regulated in S2 cells and PER abundance starts to diminish typically within 3–5 h after protein induction with only ∼10% of the substrate remaining at the end of the degradation process (Fig. 1). In contrast, when TIM is coexpressed with PER, only a small fraction of the substrate is degraded because of DBT activity while most of the PER remains bound to TIM and protected from degradation. The data show that the undegraded PER, TIM, and DBT translocate to the nucleus ∼5.5 h postinduction, suggesting that DBT does not substantially modify timing of PER/TIM entry into the nucleus. Although the average timing of nuclear entry is unaffected by DBT, presence of the kinase appears to reduce the translocation stochasticity observed in the cell population. Meyer et al. (18) reported PER/TIM nuclear entry events uniformly distributed over an interval of ∼5 h. In the present studies, over 70% of cells coexpressing DBT show PER/TIM nuclear entry within a narrower temporal window of ∼3 h (supplemental Fig. S4A). This reduction in the variation of nuclear translocation is consistent with the reconstitution of an interval timer that more closely resembles the one found in vivo. Indeed, immunostaining in pacemaker neurons shows an ∼2 h variation in the appearance of nuclear PER, when compared among multiple wild-type fly brains (26). Additionally, the PER/TIM/DBT nuclear entry data reveal that DBT can translocate to the nucleus 1–2 h prior to PER (supplemental Fig. S4B). These data further refine a model that was based on in vivo results with lower temporal resolution indicating that PER/DBT nuclear accumulation occurs concurrently (8).

The behavioral phenotypes of a number of dbt mutants have been described previously. However, a detailed molecular description of how these mutations on dbt ultimately give rise to behavioral changes in Drosophila has been missing. Here, we conducted a thorough cell-based study aimed at elucidating the effects of DBT mutations on PER turnover kinetics. To quantify our data, we formulated a multiple parameter-based hypothesis and monitored the onset of PER turnover, the degradation half-life, and the fraction of the substrate that is degraded in individual cells. Analysis of the data shows that PER half-life ranges between ∼1.2 and 6.5 h, depending on the allele of the kinase that is coexpressed with the substrate. In the presence of wild-type, short-period, and long-period alleles of DBT, PER stability appears to be independent of the substrate concentration (Figs. 2 and 3). However, in the cells expressing only endogenous DBT or overexpressing the catalytically compromised kinases DBTar and DBTK38R, PER stability varies strongly with its abundance (Fig. 4). Crucially, the substrate abundance remains steady for hours in the cells expressing high levels of PER, perhaps due to multimerization of the protein with other cellular components. The data do not reveal identity of these components but they are speculated to be PER itself or other endogenous proteins that titrate the substrate and hinder its interaction with low concentration of endogenous kinase molecules. Our findings also provide a possible explanation for why several others may have concluded that singly overexpressed PER is stable in S2 cells (6, 13, 22, 25). Because these studies sample bulk population of cells, it is likely that their measurement signal is dominated by cells expressing maximal levels of PER (equivalent of PER > 500 A.U.), the regime where our single-cell measurements show that the protein is indeed in a more stable form.

Most importantly, our data permit direct comparison between kinetic parameters determined in cell culture to behavioral measurements in vivo. In particular, a plot of PER half-life in the presence of the five different alleles of DBT and the period of daily activity from animals carrying those forms of DBT shows a remarkable correspondence between the two quantities (Fig. 5). A simple linear relationship emerges from this comparison with one noticeable outlier. The emergent model from that comparison suggests that alterations in the period of circadian rhythms that are observed in animals carrying the variants of DBT can be explained mostly by the resultant changes in the rate of PER degradation.

Two previous studies addressing DBTS activity in Drosophila concluded that the mutation causes increased kinase activity (6, 11). However, the first study did not reveal a discernible difference in PER phosphorylation or degradation when dbt was replaced by dbtS, and data from the second study (11) were derived from the human short-period mutant and substrate to argue about the Drosophila system. Since the latter work, Sekine et al. (27) have demonstrated that expression of mammalian casein kinase I in the fly does not rescue Drosophila dbt mutants, indicating that comparisons of mutant forms of the two proteins across these systems would be difficult. Our detailed measurements on PER degradation with DBTS show negligible changes on substrate stability due to the Pro-47 → Ser mutation on the kinase (Fig. 2).

In summary, the data presented here indicate that several mutations of the kinase DBT affect a common feature in the circadian clock in altering length of the period. Most of the mutations appear to modulate activity rhythm simply by changing PER stability. Deviation of the DBTS mutation from the proposed model raises the possibility that it likely affects period length through a mechanism other than changing the rate of PER turnover in vivo. Kivimae et al. (10) conjecture that DBTS might modulate PER activity as a repressor by producing a qualitatively different phosphorylation pattern of the substrate. Additionally, data from Bao et al. (28) suggest that dbtS causes early termination of per transcription, consistent with the previous finding that PER starts to decrease ∼6 h earlier in dbtS mutants compared with wild-type animals (1). Another possibility is that DBTS activity is modified by co-factors in vivo. These cofactors are missing in S2 cells but are presumably present in the nuclei of clock neurons. Regardless of the actual mechanism through which DBTS shortens period length, our results suggest it is different from that of all the other variants of DBT examined in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Deniz Top and Nicholas Stavropoulos for many helpful discussions and Deniz Top for giving SS a short course in immunoprecipitation methods. Technical support from Tiffany Lo and Joseph Steinberger are gratefully acknowledged. Portions of this work were conducted at the Bio-Imaging Resource Center of Rockefeller University.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM054339 and NS053087 (to M. W. Y.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S6.

- PER

- PERIOD

- TIM

- TIMELESS

- DBT

- Doubletime

- DBTS

- doubletime-short.

REFERENCES

- 1. Price J. L., Blau J., Rothenfluh A., Abodeely M., Kloss B., Young M. W. (1998) Cell 94, 83–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kloss B., Price J. L., Saez L., Blau J., Rothenfluh A., Wesley C. S., Young M. W. (1998) Cell 94, 97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rothenfluh A., Abodeely M., Young M. W. (2000) Curr. Biol. 10, 1399–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Suri V., Hall J. C., Rosbash M. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 7547–7555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grima B., Lamouroux A., Chélot E., Papin C., Limbourg-Bouchon B., Rouyer F. (2002) Nature 420, 178–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ko H. W., Jiang J., Edery I. (2002) Nature 420, 673–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chiu J. C., Vanselow J. T., Kramer A., Edery I. (2008) Genes Dev. 22, 1758–1772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kloss B., Rothenfluh A., Young M. W., Saez L. (2001) Neuron 30, 699–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Preuss F., Fan J. Y., Kalive M., Bao S., Schuenemann E., Bjes E. S., Price J. L. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 886–898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kivimae S., Saez L., Young M. W. (2008) PLoS Biol. 6, 1570–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gallego M., Eide E. J., Woolf M. F., Virshup D. M., Forger D. B. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 10618–10623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yu W., Zheng H., Price J. L., Hardin P. E. (2009) Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 1452–1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Muskus M. J., Preuss F., Fan J. Y., Bjes E. S., Price J. L. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 8049–8064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nawathean P., Rosbash M. (2004) Mol. Cell 13, 213–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saez L., Meyer P., Young M. W. (2007) Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 72, 69–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cyran S. A., Yiannoulos G., Buchsbaum A. M., Saez L., Young M. W., Blau J. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 5430–5437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thummel C. S., Pirrotta V. (1991) Drosophila Information Newsletter, page 71 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meyer P., Saez L., Young M. W. (2006) Science 311, 226–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Deleted in proof.

- 20. Suri V., Lanjuin A., Rosbash M. (1999) Eur. Mol. Biol. Org. J. 18, 675–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Price J. L., Dembinska M. E., Young M. W., Rosbash M. (1995) Eur. Mol. Biol. Org. J. 14, 4044–4049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ko H. W., Kim E. Y., Chiu J., Vanselow J. T., Kramer A., Edery I. (2010) J. Neurosci. 30, 12664–12675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Landskron J., Chen K. F., Wolf E., Stanewsky R. (2009) PLoS Biol. 7, 820–835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tyson J. J., Hong C. I., Thron C. D., Novak B. (1999) Biophys. J. 77, 2411–2417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sathyanarayanan S., Zheng X., Xiao R., Sehgal A. (2004) Cell 116, 603–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Curtin K. D., Huang Z. J., Rosbash M. (1995) Neuron 14, 365–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sekine T., Yamaguchi T., Hamano K., Young M. W., Shimoda M., Saez L. (2008) J. Biol. Rhythms 23, 3–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bao S., Rihel J., Bjes E., Fan J. Y., Price J. L. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 7117–7126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.