Abstract

Currently there is considerable interest in the legislative debate around generic biological drugs or “biosimilars” in the EU and US due to the large, lucrative market that it offers to the industry. While some countries have issued a few regulatory guidelines as well as product specific requirements, there is no general consensus as to a single, simple mechanism similar to the bioequivalence determination that leads to approval of generic small molecules all over the world. The inherent complex nature of the molecules, along with complicated manufacturing and analytical techniques to characterize them make it difficult to rely on a single human pharmacokinetic study for assurance of safety and efficacy. In general, the concept of comparability has been used for evaluation of the currently approved “similar” biological where a step by step assessment on the quality, preclinical and clinical aspects is made. In India, the focus is primarily on the availability and affordability of life-saving drugs. In this context every product needs to be evaluated on its own merit irrespective of the innovator brand. The formation of the National Biotechnology Regulatory Authority may provide a step in the right direction for regulation of these complex molecules. However, in order to have an efficient machinery for initial approval and ongoing oversight with a country-specific focus, cooperation with international authorities for granting approvals and continuous risk-benefit review is essential. Several steps are still needed for India to be perceived as a country that leads the world in providing quality biological products.

Keywords: Biologics, Regulations, Guidelines, Equivalence, Comparability, Biosimilar

We are now in the twenty-fifth anniversary year of the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (better known as the Hatch Waxman Act), the landmark US regulation that jump-started the generic pharmaceutical industry. The legislation provided the required impetus to make not just cheaper price alternative medicines available to US consumers but stimulated the emergence of the Indian pharmaceutical industry which is now the dominant supplier of generic drugs to the USA.

The regulatory pathway for bringing generic drugs to market is the abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) process which relies on proving bioequivalence to the listed reference product and showing equivalent product quality. Since duplication of proof of safety and efficacy in the preclinical and clinical setting is not required, there are significant cost savings in bringing a copy of a small chemical molecule to market. This model has been so successful in economic terms that almost 7 out of 10 prescriptions in the US are now generic and for the vast majority of products there is no concern in substitution of a generic equivalent for a brand-name prescription.1

The success story of generic small molecule drugs has stimulated interest in the pharmaceutical and biotech industry for applying an analogous approach towards the highly lucrative biologics business. But biologic drugs are very different from small molecules both in their final form and in the process required to produce and control their quality. It is therefore difficult to find a simple, precise “regulatory” definition of biologics. However, biologics are generally understood to be drugs derived from an organic source. Thus, biologics may be obtained or created from living organisms, either naturally or via genetic manipulation or are manufactured from building blocks of living organisms. They demonstrate considerable molecular complexity and may comprise a diversity of molecular forms. Their larger size and heterogeneity make it difficult for complete characterization via physicochemical analysis which is possible for synthetic chemical entities. In general, biologic drugs are more expensive and the cost of a yearly treatment may run into thousands of dollars for some. They are therefore ideal targets for developing cheaper alternatives.

US FDA definition - A “biological product” means a virus, therapeutic serum, toxin, antitoxin, vaccine, blood, blood component or derivative, allergenic product, or analogous product, or arsphenamine or derivative of arsphenamine (or any other trivalent organic arsenic compound), applicable to the prevention, treatment, or cure of a disease or condition of human beings (Public Health Service Act Sec. 351(i)).

Given the complexity of the final biologic product, it is clear that the nature of the manufacturing process is also complicated. In addition to aspects that are disclosed in regulatory applications, there may still be several aspects which might be held as trade secrets, thereby making it practically impossible for another company to make an identical copy of a biologic drug. While changing a host cell line or vector will definitely impact the product, effects of minor changes like temperature used in the manufacturing process may have an effect on the final characteristics of the biologic drug, including its safety and efficacy. It has been stated often that for a biologic, “the process defines the product”. Thus, while it may be possible to make a similar product, it may not be truly bioequivalent. As a result, even the term used to describe these similar biologic drugs has not been standardized globally. While the parallel term for a biologic generic may intuitively be “biogeneric”, the accepted term in Europe and Canada is “biosimilar” and the preferred term in the US is “follow-on biologic”.

Given these differences among innovator biologics and their “similar” counterparts, there is considerable hesitation on the part of the regulatory agencies to follow an abbreviated approval path similar to one widely used for generic small molecules.

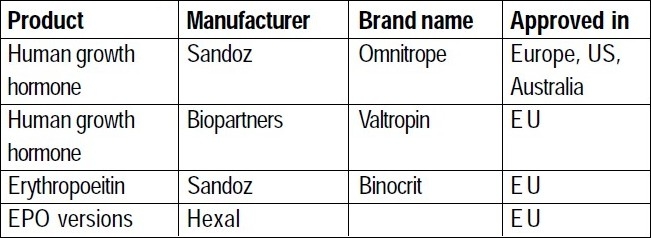

Table 1.

Some Approved biosimilars

Status of biosimilar regulation in Europe

EMEA Guidelines for Similar Biological Medical Products ( CHMP/437/04, 30 October 2005).2

EMEA's Guideline on Similar Biological Medicinal Products Containing Biotechnology-derived Proteins as Active Substance: Nonclinical and Clinical Issues (EMEA/ CHMP/BMWP/42832/2005).3

EMEA's Guideline on Similar Biological Medicinal Products Containing Biotechnology-derived Proteins as Active Substance: Quality Issues, EMEA/CHMP/49348/05.4

In Europe, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP), the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) led the way for biosimilars, by issuing its first specific regulatory guidance in October 2005. Two general guidance documents addressing quality and nonclinical and clinical perspectives (June 2006), five product-specific annexes on nonclinical and clinical issues (June-July 2006) and a manufacturing change comparability guideline (November 2007) are now available.

Status of Biosimilar Regulation in US

In US, in March 2009, Representative Henry Waxman introduced H.R. 1427 to the Congress “Promoting Innovation and Access to Life-saving Medicines Act”, which authorizes FDA to approve follow-on biologics in an abbreviated manner. It has market exclusivity clauses with time frames similar to ones used currently for drugs. Other bills are expected to follow in the 2009 legislative agenda in order to establish a pathway for approval of these follow-on biologics. The contentious issues as expected, are focused around the duration of exclusivity benefits granted to innovators. The issue of substitutability of followon biologics for reimbursement is also an important one as the legislators debate the merits of each bill.

Korea and Singapore have released draft guidelines on biosimilars in 2009. The Singapore guideline is derived mainly from the EMEA guidelines and defines a similar biological/ biosimilar product as “a biological medicinal product referring to an existing registered product, submitted for medicinal product registration by an independent applicant, and is subject to all applicable data protection periods and/or intellectual property rights for the original product”. In addition to specifying the requirements for biosimilars, the guidance requires that the product have prior approval in countries such as Australia, Canada, EMEA or US.

Indian scenario

The Indian biotech industry is a thriving industry which got its start from vaccine manufacturing. In addition to meeting domestic demands, the Indian vaccine industry also fulfils export requirements to a large extent. Therefore it is evident that manufacturing expertise in producing biologic products of required export quality already exists in the country. What is not readily evident is whether these products can prove to be “comparable” to innovator products when we look into all categories of biologics.

The evolution of regulations governing pharmaceuticals in India has historically been driven by the need to make essential medicines accessible to patients. Access encompasses availability and affordability. It applies to medicines for all indications, acute and chronic illness, small molecules and biologics alike. The absence of product patent regulations for drugs marked a period in the country's history where it was imperative to make inexpensive medicinal products available to the masses – it did not matter whether these products were innovator-made or copies thereof. In the post-TRIPS era however, there is need to offer and enforce adequate protections for patentable drugs, particularly biologics that inherently involve huge investments in R & D, manufacture and clinical development.

Today, several biologics have been approved in India , including recombinant human insulin, recombinant human erythropoietin (EPO), interferon (IFN), granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCSF). The versions of biologics available in India are typically products whose patents have expired or do not exist in India. Therefore, from a technical standpoint, there is no concern about patent infringement regarding these (there are no patents in India for these products). If a biosimilar results in a price drop of 30%, it is a significant improvement to patients who may now be able to afford this generic version of a life-saving drug. In many ways, the debate about biosimilars that rages across the developed world and regulated markets is irrelevant to India where the central concern revolves around access.

Partly due to the dearth of appropriate resources and experience, Indian regulators have sought to mimic regulations already in use in the developed world without much customization. A host of agencies have been created to address the issues brought forth by biologics.

List of agencies

Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR)

Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO)

Department of Biotechnology (DBT)

Genetic Engineering Approval Committee (GEAC)

Recombinant DNA advisory Committee (RDAC)

Review Committee on Genetic Manipulation (RCGM)

Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBSC)

National Centre for Biological Sciences

National Control Laboratory for Biologicals

Notwithstanding the above, there is clarity on the fact that biologics and drugs need to be scrutinized differently. With this in mind, the DBT has been given the mandate to set up the National Biotechnology Regulatory Authority (NBRA). This is envisaged as an independent, autonomous and professionally led body to provide a single window mechanism for biosafety clearance of genetically modified products and processes.

Before such an organization can be effectively implemented, it will be necessary to put in place appropriate new legislation, namely the “National Biotechnology Regulatory Act” or the NBR Act. Draft establishment plan and “Draft National Biotechnology Regulatory Bill, 2008” are currently available on the DBT website for comments. The responsibility of consolidating the feedback has been entrusted to Biotech Consortium India Limited (BCIL). The draft bill envisions the scope of this authority to encompass research, manufacture, import and use of genetically engineered organisms and products derived thereof.

Global concerns regarding product safety and quality

Every drug/biologic manufacturer needs to own the responsibility for putting a high quality, safe drug on the market, after appropriate review and approval by the concerned regulatory authority. While the safety of original biologics products is assured by the innovator by adherence to rigorous standards required for approval, the resistance towards biosimilars on the part of regulators, stems from the concern that an abbreviated approval process may not be adequate to ensure safe performance of the product in the market. For a manufacturer looking to get into the biosimilar market, he needs to overcome major challenges in making a complex product, getting regulatory approval by satisfying stringent criteria and then selling it in the market. Typically, facilities required for manufacture of biologicals are very expensive and the kind of infrastructure required to meet high regulatory expectations is limited to only a few companies. Clinical trial expenditure and ongoing analysis requires compliance to pharmacopoeial monographs when available and access to reference standards, which are not always available.

The cornerstone of generic drug approvals has been the concept of bioequivalence, using equivalence of pharmacokinetic parameters as surrogates for clinical efficacy. But in the context of biosimilars, the concept of comparability is the one used to make such an evaluation. Comparability protocols are used for chemistry, manufacturing and controls (CMC) sections to make the case on the quality aspects of the product. Preclinical testing requires knowledge of study designs used by innovator in order to truly compare performance of the biosimilar. For clinical evaluation, at least one clinical comparability trial is required to demonstrate comparability (non-inferiority in terms of efficacy to innovator and comparable safety profile). But long term safety issues remain unaddressed for biosimilars, requiring thorough postmarketing studies and pharmacovigilance and adequate risk management plans.

In terms of preclinical studies, for biologics, pharmacodynamic endpoints are more relevant than pharmacokinetics, which is the key measure with small molecules. For animal safety studies, choice of appropriate animal species and duration of studies are important criteria for proving comparability. Clinically, comparative PK/PD study is required to compare the reference and biosimilar product. However, clinical trial design selection and a thorough understanding and a priori statement of margins chosen for comparability must be stated for meaningful evaluation of data.

A way forward for India

In today's scenario, India needs to focus on quality of each biological product per se, whether that is demonstrated through comparability or by its own merit; and assurance of safety through appropriate regulatory review and approval of available data.

Irrespective of the authority entrusted to oversight of biologics, the debate on appropriate level of regulatory scrutiny for biologics will continue to focus on requiring adequate characterization while balancing cost, with the overall goal of having a much needed product on the market with reasonable assurance of efficacy and safety. Intense discussion on publication of appropriate monographs in the Indian Pharmacopeia and availability of reference standards continues amidst regulatory circles. Indian manufacturers have always sought to enter new markets and have voluntarily raised the bar in order to secure approvals for their products in the regulated markets where profit margins are high. From a facility infrastructure and systems point of view, most companies eyeing the regulated markets for their products will most likely fulfil expectations. State-of-the art analytical techniques are available within the industry. Therefore from a quality standpoint, biologic products made in India should not have any trouble in meeting market expectations. However, physicochemical characterization of a biologic product and compliant facilities form only one part of the evaluation required to demonstrate product comparability.

The practical way forward for approval of biosimilar products in India would have to be unique to the Indian context while staying rooted to scientific basics and keeping in mind the needs and limitations of the country. The large majority of biosimilars introduced in India would be products whose patents have expired and where the “original innovator” product may not be approved in the country. It is also possible that no patent exists in India for some products and therefore , originator and similars coexist. For all products, the question of available reference standards and monographs would continue to remain. The next wave of biologics of commercial interest to the industry will become a burning issue where the regulator cannot expect to wait to see how the legislation is crafted in the US or elsewhere before making a move.

In my opinion, it seems that India, having the benefit of in-house (in-country) expertise in the area, should utilize the various agencies currently entrusted with splintered tasks and responsibilities to come up with working group or taskforce whose goal is to develop product-specific guidelines for approval. These can be developed using available worldwide regulatory knowledge by signing appropriate MOUs if necessary, studying the scientific literature and current industry standards and practice with respect to characterization, focusing on specific areas of unique concern for each product and proposing an approval path. These guidelines can be widely disseminated in the community. There will still be grey areas that need clarification and in such cases, a system for formal meeting with members of the working group/taskforce can be instituted, similar to the scientific advice that is currently available through the EMEA or individual European country competent authorities.

As a nation that takes pride in being the “exporter to the world” in the arena of pharmaceuticals, it behooves not just the regulators but all those in the regulatory affairs profession in India to support such initiatives to make life-saving products available to our countrymen that are unquestionably of the highest standards in terms of quality, safety and efficacy such that we become the supplier of choice when it comes to exporting biosimilars to markets in every corner of the world.

References

- 1. www.fda.gov. -Generic drugs, fact sheet http://wwwfdagov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/Buying Using Medicine SafelyUnderstandingGenericDrugs/ucm167991.htm .

- 2. http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/biosimilar/043704en.pdf .

- 3. http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/biosimilar/9452605en.pdf .

- 4. http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/biosimilar/4934805en.pdf .