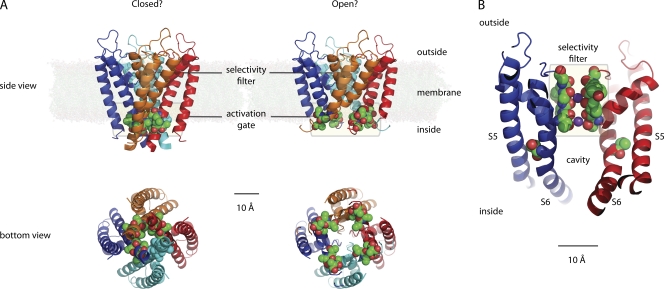

Four α-helical segments at the intracellular entrance to the ion conduction pathway splaying open is the conventional imagery of a K+ channel opening to allow K+ ions and co-traversing water molecules to hop through the channel’s pore (Fig. 1) (Armstrong, 2003; Swartz, 2004). This view of K+ channel gating—already depicted in numerous textbooks—has been derived largely from K+ channel crystal structures published over the last decade, most notably of the voltage-independent 2TM K+ channels KcsA (Doyle et al., 1998), MthK (Jiang et al., 2002), and KirBac1.1/3.1 (Kuo et al., 2003, 2005), and the voltage-dependent 6TM K+ channels KvAP (Jiang et al., 2003) and Kv1.2 (Long et al., 2005, 2007).

Figure 1.

(A) Probable closed (Protein Data Bank accession no. 1R3J) and open (PDB no. 3F5W) conformations of the 2TM channel KcsA. The four subunits are colored differently, and those amino acid residues likely to form the activation gate are shown using spheres. (B) Probable open conformation of the voltage-gated K+ channel Kv1.2/2.1 (PDB no. 2R9R). Only the pore segments of two of the four subunits are shown. The residues in the selectivity filter (top) and T402 in S6 postulated to be equivalent to M314 in Slo1 are illustrated using spheres, and the purple spheres are K+ ions. This figure was prepared using MacPyMol.

All of these structures display in the outer third of their pore regions a structurally conserved K+ selectivity filter (Doyle et al., 1998), whose form is consistent with many previous functional measurements and presents a unified picture of K+ selectivity (Armstrong, 2003). Exquisite K+ selectivity contemporaneous with a high transport rate is achieved via the precise arrangement of oxygen atoms so as to optimally coordinate multiple dehydrated K+ ions as they pass single file through the selectivity filter separated by intervening water molecules (Armstrong, 2003).

Have these structures also lead us to a unified theory of activation gating? At first it appeared so. Comparisons, for example, of the crystal structures of KcsA, a closed-channel structure, and MthK, an open-channel structure, reinforced the notion, developed from Cd2+-bridging experiments with the Shaker K+ channel (Holmgren et al., 1998), that the main ion conduction gate of K+ channels (“activation gate”) is formed by the bundle crossing of the inner portion of the four pore domain helices (Fig. 1 A). Indeed, in the KcsA structure, this region narrows to less than the dehydrated diameter of a K+ ion (∼2.66 Å), apparently forming an ion and water-tight seal, whereas in the MthK structure, the pore at the bundle crossing has a diameter of ∼12 Å (Jiang et al., 2002), more than sufficient to allow hydrated K+ ions to readily pass. Thus, these types of comparisons, in conjunction with experiments that demonstrated that in the closed Shaker channel the bundle crossing also forms an ion and water-tight seal (del Camino and Yellen, 2001; Kitaguchi et al., 2004), lead to the following standard view of K+ channel activation gating. The activation gate of the K+ channel is formed by the bundle crossing of the inner pore helices. The gate separates two polar milieus containing K+ ions and water molecules: the intracellular compartment and a large pore cavity lined by mostly nonpolar residues. Access to the pore cavity from the intracellular compartment is possible only when the activation gate is open (Liu et al., 1997). The pore cavity is large enough to accommodate select ions or inhibitors, and when the channel closes, it can trap such molecules in the pore cavity, leading to measurable changes in ionic current kinetics (Armstrong, 1971).

Indeed, the notion that the helical bundle crossing forms the activation gate became so appealing that some considered the structural underpinnings of gating to be an open-and-shut case and speculated that perhaps other channel types similar in overall architecture to K+ channels may work in the same way. This appealing generalization, however, has turned out not to be true. The cyclic nucleotide–gated (CNG) channel is a nonselective cation channel similar in overall structure to the Kv family of K+ channels. The CNG channel opens in response to the binding of cyclic nucleotides to the channel’s large intracellular domain (Kaupp and Seifert, 2002), but here it has been demonstrated that the bundle crossing formed by the channel’s four S6 helices is leaky and does not prevent ion flux (Flynn and Zagotta, 2001). Indeed, amino acid residues presumed to be located extracellular to the bundle crossing, and thus inside the pore cavity, can be modified equally well by small reagents whether the channel is open or closed (Flynn and Zagotta, 2003). The activation gate functionally coupled to agonist binding in the CNG channel, therefore, must exist elsewhere in the pore region; the available evidence suggests that the selectivity filter contains the activation gate (Contreras and Holmgren, 2006; Contreras et al., 2008).

The apparent dichotomy between K+ channels and CNG channels concerning the location of the activation gate might reasonably lead to the following plausible notion: highly selective K+ channels, such as the Shaker channel, use the S6 bundle crossing as the activation gate, whereas less selective cation channels, such as the CNG channels, use the selectivity filter region as their activation gate. That is, perhaps the textbook illustration of the inner helices coming together to form an ion/water-tight seal still holds true for K+ channels but not necessarily for other channels.

Bearing on this issue, however, is the work done over the last few years on the large-conductance Ca2+- and voltage-gated K+ channel, also known as BKCa, maxiK, Slo1, and KCa1.1. This channel is activated by membrane depolarization and/or the binding of Ca2+ to its large intracellular domain (Cox et al., 1997; Rothberg and Magleby, 2000; Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002), and it is highly K+ selective and therefore, under the aforementioned hypothesis, expected to have an activation gate formed by its S6 bundle crossing. Contrary to this expectation, the pore domain of the BKCa channel appears to be quite distinct from that of Kv channels. Multiple studies indicate that the BKCa channel has a larger internal vestibule and, when open, a wider intracellular mouth than do Kv channels (Li and Aldrich, 2004; Brelidze and Magleby, 2005; Geng et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2011). And more telling, Wilkens and Aldrich (2006) have found that a large quarternary ammonium compound, bbTBA, can pass through the BKCa channel’s bundle crossing and block the BKCa channel near the selectivity filter even when the channel is closed (but see also Tang et al., 2010). Similarly, cysteine-modifying reagents appear to be able to move through the bundle crossing of the BKCa channel easily from the intracellular side (Zhou et al., 2011). Thus, in the BKCa channel, structural rearrangements occur at or near the channel’s bundle crossing as the channel closes (Brelidze and Magleby, 2005; Li and Aldrich, 2006); however, they are not sufficient to prevent the access of small molecules to the internal pore and most likely K+ ions as well. Where then is the activation gate of the BKCa channel?

An important clue to this question is provided by Chen and Aldrich in this issue of JGP. Their study identifies a single residue M314, halfway down S6, that appears to change conformation during the opening of the BKCa channel. Indeed, when M314 is mutated to an aspartate (M314D), the single added negative charge in each subunit creates a constitutively active channel that is open ∼80% of the time, even in the absence of Ca2+ and at far negative voltages. However, when a neutral asparagine is placed at this position, no such constitutive activity is observed. From this result and the results from a series of other mutations made at position 314, Chen and Aldrich (2011) postulated that in the wild-type channel, M314 moves during gating; its side chain is exposed to the watery polar pore when the channel is open and more buried within the nonpolar pore wall when the channel is closed. Thus, according to their idea, any perturbation that increases the hydrophilicity of the side chain at position 314 would be expected to favor the open state of the channel. To elegantly test this prediction, Chen and Aldrich (2011) placed a histidine at position 314 and examined whether its protonation at low pH, thus the insertion of a positive charge, would stabilize the open channel. The results are quite compelling. The M314H channel is highly pH sensitive, with low pH (protonated imidazole) favoring channel opening, and high pH (deprotonated imidazole) favoring channel closing. Thus, the side chain of M314 appears to turn toward the pore as the channel opens. This finding is intriguing because homology models based on the crystal structures of other K+ channels (Fig. 1 B) (Yuan et al., 2010) suggest that M314 is not in the selectivity filter, nor near the bundle crossing, but rather it is along the wall of the pore cavity, hinting at the limited applicability of such homology models to the BKCa channel (Zhou et al., 2011). Importantly, the results of Chen and Aldrich (2011) do not necessarily show that M314 actually forms the part of the activation gate of the channel that physically occludes ion passage. Indeed, it may be that motions in the deep pore may be required for pore occlusion elsewhere, perhaps, as in the CNG channel, in the selectivity filter (Wilkens and Aldrich, 2006).

Indeed, the selectivity filter has been implicated previously as an auxiliary gate for other K+ channels (Kurata and Fedida, 2006). Some Shaker/Kv channels undergo an inactivation process termed “C-type” inactivation (Hoshi et al., 1991), and numerous mutagenesis studies have shown that the nature of the residues in the selectivity filter is of critical importance for this gating phenomenon (Kurata and Fedida, 2006). The precise atomic changes that underlie C-type inactivation in Shaker/Kv channels remain to be elucidated; however, structural studies of the KcsA channel (Cuello et al., 2010) suggest that C-type inactivation involves a deformation of the selectivity filter that renders the filter unable to coordinate K+ ions. Could a similar structural change be the atomic basis of the activation gate of the BKCa channel (Wilkens and Aldrich, 2006)? Is the activation gate of the BKCa channel functionally similar to the C-type inactivation gate of Shaker, or is their real occlusion going on within the deep pore, perhaps via a “dewetting,” as has been suggested recently by molecular dynamics simulations of K+ permeating the Kv1.2 pore (Jensen et al., 2010)?

Although the definitive answers to these questions are unlikely to arrive soon, if the BKCa channel’s activation gate is analogous to the Shaker channel’s C-type inactivation gate, then some experiments might be performed to demonstrate this correspondence. For example, C-type inactivation is sensitive to the nature of the ions permeating the channel, and it becomes faster and more complete as the occupancy of K+ in the selectivity filter is reduced (López-Barneo et al., 1993). If the structural changes underlying C-type inactivation in Shaker and activation in BKCa are similar, one might therefore expect BKCa channel activation also to be sensitive to the manipulation of permeant ions. Indeed, supporting this notion, it has already been shown that BKCa channel activation is inhibited when K+ is replaced by thalium as the permeating ion (Piskorowski and Aldrich, 2006). Regardless of the precise mechanism, however, what is clear is that the molecular mechanism underlying BKCa channel activation is not an open-and-shut case, and it involves structural rearrangements in more parts of the pore than previously understood.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Clay Armstrong for discussion.

References

- Armstrong C.M. 1971. Interaction of tetraethylammonium ion derivatives with the potassium channels of giant axons. J. Gen. Physiol. 58:413–437 10.1085/jgp.58.4.413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong C.M. 2003. Voltage-gated K channels. Sci. STKE. 2003:re10 10.1126/stke.2003.188.re10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brelidze T.I., Magleby K.L. 2005. Probing the geometry of the inner vestibule of BK channels with sugars. J. Gen. Physiol. 126:105–121 10.1085/jgp.200509286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Aldrich R.W. 2011. Charge substitution for a deep-pore residue reveals structural dynamics during BK channel gating. J. Gen. Physiol. 138:137–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras J.E., Holmgren M. 2006. Access of quaternary ammonium blockers to the internal pore of cyclic nucleotide–gated channels: implications for the location of the gate. J. Gen. Physiol. 127:481–494 10.1085/jgp.200509440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras J.E., Srikumar D., Holmgren M. 2008. Gating at the selectivity filter in cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:3310–3314 10.1073/pnas.0709809105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D.H., Cui J., Aldrich R.W. 1997. Allosteric gating of a large conductance Ca-activated K+ channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 110:257–281 10.1085/jgp.110.3.257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello L.G., Jogini V., Cortes D.M., Perozo E. 2010. Structural mechanism of C-type inactivation in K+ channels. Nature. 466:203–208 10.1038/nature09153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Camino D., Yellen G. 2001. Tight steric closure at the intracellular activation gate of a voltage-gated K+ channel. Neuron. 32:649–656 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00487-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle D.A., Morais Cabral J., Pfuetzner R.A., Kuo A.L., Gulbis J.M., Cohen S.L., Chait B.T., MacKinnon R. 1998. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 280:69–77 10.1126/science.280.5360.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn G.E., Zagotta W.N. 2001. Conformational changes in S6 coupled to the opening of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Neuron. 30:689–698 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00324-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn G.E., Zagotta W.N. 2003. A cysteine scan of the inner vestibule of cyclic nucleotide–gated channels reveals architecture and rearrangement of the pore. J. Gen. Physiol. 121:563–582 10.1085/jgp.200308819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y., Niu X., Magleby K.L. 2011. Low resistance, large dimension entrance to the inner cavity of BK channels determined by changing side-chain volume. J. Gen. Physiol. 137:533–548 10.1085/jgp.201110616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren M., Shin K.S., Yellen G. 1998. The activation gate of a voltage-gated K+ channel can be trapped in the open state by an intersubunit metal bridge. Neuron. 21:617–621 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80571-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrigan F.T., Aldrich R.W. 2002. Coupling between voltage sensor activation, Ca2+ binding and channel opening in large conductance (BK) potassium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:267–305 10.1085/jgp.20028605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi T., Zagotta W.N., Aldrich R.W. 1991. Two types of inactivation in Shaker K+ channels: effects of alterations in the carboxy-terminal region. Neuron. 7:547–556 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90367-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M.O., Borhani D.W., Lindorff-Larsen K., Maragakis P., Jogini V., Eastwood M.P., Dror R.O., Shaw D.E. 2010. Principles of conduction and hydrophobic gating in K+ channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:5833–5838 10.1073/pnas.0911691107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Lee A., Chen J., Cadene M., Chait B.T., MacKinnon R. 2002. The open pore conformation of potassium channels. Nature. 417:523–526 10.1038/417523a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Lee A., Chen J., Ruta V., Cadene M., Chait B.T., MacKinnon R. 2003. X-ray structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Nature. 423:33–41 10.1038/nature01580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupp U.B., Seifert R. 2002. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Physiol. Rev. 82:769–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaguchi T., Sukhareva M., Swartz K.J. 2004. Stabilizing the closed S6 gate in the Shaker Kv channel through modification of a hydrophobic seal. J. Gen. Physiol. 124:319–332 10.1085/jgp.200409098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo A., Gulbis J.M., Antcliff J.F., Rahman T., Lowe E.D., Zimmer J., Cuthbertson J., Ashcroft F.M., Ezaki T., Doyle D.A. 2003. Crystal structure of the potassium channel KirBac1.1 in the closed state. Science. 300:1922–1926 10.1126/science.1085028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo A., Domene C., Johnson L.N., Doyle D.A., Vénien-Bryan C. 2005. Two different conformational states of the KirBac3.1 potassium channel revealed by electron crystallography. Structure. 13:1463–1472 10.1016/j.str.2005.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata H.T., Fedida D. 2006. A structural interpretation of voltage-gated potassium channel inactivation. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 92:185–208 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2005.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Aldrich R.W. 2004. Unique inner pore properties of BK channels revealed by quaternary ammonium block. J. Gen. Physiol. 124:43–57 10.1085/jgp.200409067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Aldrich R.W. 2006. State-dependent block of BK channels by synthesized Shaker ball peptides. J. Gen. Physiol. 128:423–441 10.1085/jgp.200609521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Holmgren M., Jurman M.E., Yellen G. 1997. Gated access to the pore of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Neuron. 19:175–184 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80357-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S.B., Campbell E.B., Mackinnon R. 2005. Crystal structure of a mammalian voltage-dependent Shaker family K+ channel. Science. 309:897–903 10.1126/science.1116269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S.B., Tao X., Campbell E.B., MacKinnon R. 2007. Atomic structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel in a lipid membrane-like environment. Nature. 450:376–382 10.1038/nature06265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Barneo J., Hoshi T., Heinemann S.H., Aldrich R.W. 1993. Effects of external cations and mutations in the pore region on C-type inactivation of Shaker potassium channels. Receptors Channels. 1:61–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piskorowski R.A., Aldrich R.W. 2006. Relationship between pore occupancy and gating in BK potassium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 127:557–576 10.1085/jgp.200509482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg B.S., Magleby K.L. 2000. Voltage and Ca2+ activation of single large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels described by a two-tiered allosteric gating mechanism. J. Gen. Physiol. 116:75–99 10.1085/jgp.116.1.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz K.J. 2004. Opening the gate in potassium channels. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:499–501 10.1038/nsmb0604-499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q.Y., Zhang Z., Xia X.M., Lingle C.J. 2010. Block of mouse Slo1 and Slo3 K+ channels by CTX, IbTX, TEA, 4-AP and quinidine. Channels (Austin). 4:22–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkens C.M., Aldrich R.W. 2006. State-independent block of BK channels by an intracellular quaternary ammonium. J. Gen. Physiol. 128:347–364 10.1085/jgp.200609579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan P., Leonetti M.D., Pico A.R., Hsiung Y., MacKinnon R. 2010. Structure of the human BK channel Ca2+-activation apparatus at 3.0 Å resolution. Science. 329:182–186 10.1126/science.1190414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Xia X.M., Lingle C.J. 2011. Cysteine scanning and modification reveal major differences between BK channels and Kv Channels in the inner pore region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 10.1073/pnas.1104150108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]