Abstract

Purpose: Mentoring plays an important role in students' performance and career. The authors of this study assessed the need for mentoring among medical students and established a novel large-scale mentoring program at Ludwig-Maximilians-University (LMU) Munich School of Medicine.

Methods: Needs assessment was conducted using a survey distributed to all students at the medical school (n=578 of 4,109 students, return rate 14.1%). In addition, the authors held focus groups with selected medical students (n=24) and faculty physicians (n=22). All students signing up for the individual mentoring completed a survey addressing their expectations (n=534).

Results: Needs assessment revealed that 83% of medical students expressed overall satisfaction with the teaching at LMU. In contrast, only 36.5% were satisfied with how the faculty supports their individual professional development and 86% of students voiced a desire for more personal and professional support. When asked to define the role of a mentor, 55.6% "very much" wanted their mentors to act as counselors, arrange contacts for them (36.4%), and provide ideas for professional development (28.1%). Topics that future mentees "very much" wished to discuss included research (56.6%), final year electives (55.8%) and experiences abroad (45.5%).

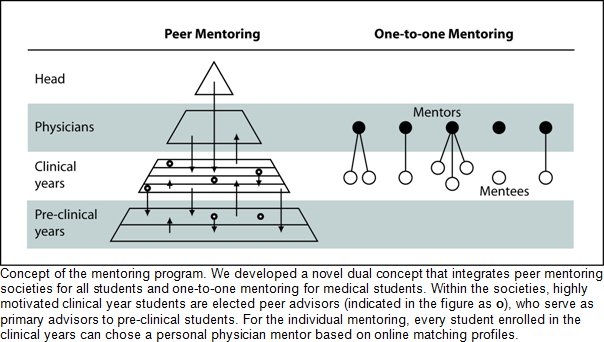

Conclusions: Based on the strong desire for mentoring among medical students, the authors developed a novel two-tiered system that introduces one-to-one mentoring for students in their clinical years and offers society-based peer mentoring for pre-clinical students. One year after launching the program, more than 300 clinical students had experienced one-to-one mentoring and 1,503 students and physicians were involved in peer mentoring societies.

Keywords: medical students, mentoring, support, counseling

Abstract

Hintergrund: Mentoring ist eine wichtige Stütze in der Karriere von Studierenden. In der vorliegenden Untersuchung dokumentieren wir den Mentoring-Bedarf der Medizinstudierenden an der Medizinischen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (LMU) und beschreiben die Einführung eines innovativen, umfassenden Mentorenprogramms.

Methoden: Die Bedarfsanalyse wurde durch eine an alle Medizinstudierenden der Medizinischen Fakultät gerichtete Online-Umfrage durchgeführt (n=578 von 4.109 Studenten, Rücklauf 14,1%). Außerdem führten wir Fokusgruppen mit Medizinstudenten (n=24) und ärztlichem Personal (n=22) durch. Schließlich wurden alle Studierenden, die sich für das individuelle Mentorenprogramm interessierten, zu ihren Erwartungen befragt (n=534).

Ergebnisse: 83% der Medizinstudierenden äußerten Zufriedenheit mit dem aktuellen Münchener Curriculum. Im Gegensatz dazu fühlten sich nur 36.5% der Studierenden unserer großen Fakultät ausreichend im Studium betreut, und 86% der Studierenden äußerten den Wunsch nach mehr Betreuung. Die Rolle ihres Mentors wünschten sich 55.6% "sehr" als Berater, Kontaktvermittler (36.4%) und Ideenlieferant (28.1%). Die Themen, die angehende Mentees im Vorfeld "sehr" mit ihren Mentoren besprechen wollten, waren die Doktorarbeit (56.6%), das Praktische Jahr (55.8%) und Auslandsaufenthalte (45.5%).

Schlussfolgerungen: Wir haben anhand der Erkenntnisse unserer Bedarfsanalyse ein innovatives, zweigleisiges Konzept entworfen, das aus einem beliebig skalierbaren individuellen Mentorenprogramm für Studierende in klinischen Semestern und einem Peer Mentoring-Programm für sämtliche Medizinstudierende unserer Fakultät besteht. Ein Jahr nach der Initiierung des Programms haben über 300 Studierende im klinischen Studienabschnitt einen individuellen Mentor aus der Fakultät ausgewählt und 1.503 Studierende und Ärzte nahmen am Peer Mentoring teil.

Introduction

"Everyone who makes it has a mentor." [1] There is increasing evidence that mentoring is a key element for a successful career in academic medicine [2], [3], [4], [5] Despite methodological limitations in measuring its effectiveness [6], mentoring has been found to be essential for supporting and facilitating a trainee’s education, acquisition of clinical and research skills, and career development [4], [5], [7]. Mentoring and professional networking were identified as key characteristics of junior physicians in academic medicine as compared to their non-academic peers [8], [9].Lack of mentoring was identified as one of the most important factors hindering career success in academic medicine [10]. In a recent systematic review, having a mentor correlated with increased research activities, productivity in research and the number of publications and grants for junior academic physicians [4]. Among medical students, having a mentor significantly increased the odds of participating in research before and during medical school [11]. Mentoring has also played a significant role among underrepresented minorities in medicine [12]. In contrast to the thorough appreciation of mentoring in the U.S. and U.K., a mentoring culture is only beginning to develop in Germany.

It is documented that many young medical professionals have severe difficulties in finding or identifying a mentor [13]. This might be because they are intimidated to address senior faculty or unaware of the potential benefits of mentoring [14]. Many institutions have tried to overcome these obstacles by establishing formal mentoring programs that facilitate the formation of mentor-mentee-relationships. However, a number of these programs accept only resident physicians and junior faculty but no medical students as mentees. A cross-sectional study at the University of California found that 36% of 3rd and 4th year medical students had a mentor. Little is known about the prevalence of mentoring at medical schools in Germany. In 2000, mentoring programs with personally allocated mentors were offered by 10 (33%) medical schools in Germany [15]. This study has been criticized for confusing the concepts of mentoring, tutoring, and counseling [16].

The term “mentor” has more than twenty different definitions in the literature and there is no consensus on any operational definition [6]. It seems possible to identify certain basic elements of mentoring relationships that can be generally agreed upon. A mentoring relationship is personal in nature, long lasting, and it involves direct interaction. It furthermore involves emotional and psychological support, direct assistance with career and professional development and role-modeling. It is reciprocal, where both the mentor and the mentee derive emotional and tangible benefits but emphasizes the mentor’s greater experience, influence and achievement within a particular field [6]. Mentoring is different from role-modeling since the mentor is actively engaged in an explicit two-way relationship that evolves and develops over time [17].

The literature is sparse about the specific needs for mentoring among medical students. Also, there is insufficient data about the feasibility of a mentoring program for very large numbers of students. Therefore, we conducted a detailed quantitative and qualitative analysis to assess the need for mentoring among medical students at the medical school of Ludwig-Maximilians-University (LMU), Munich. LMU Munich hosts the second largest medical school in the country with more than 4,000 students enrolled in the MD program. This large number of students represents one of the major challenges to implementing a mentoring program. The primary purpose of this study was to conduct a needs assessment about mentoring in a German medical school, and based on the results develop a formal mentoring program that could offer mentoring to all students of our medical school. The novel, student-centered concept involves a society-model of peer-mentoring for pre-clinical students as well as physicians as one-to-one mentors for students in their clinical years. This concept can serve as a model for the implementation of mentoring programs at similarly large educational institutions.

Methods

To assess the need for mentoring among medical students at LMU, we performed a preliminary survey in 2007, focus groups in Spring of 2008 and a sign-up survey in the summer of 2008.

Preliminary survey

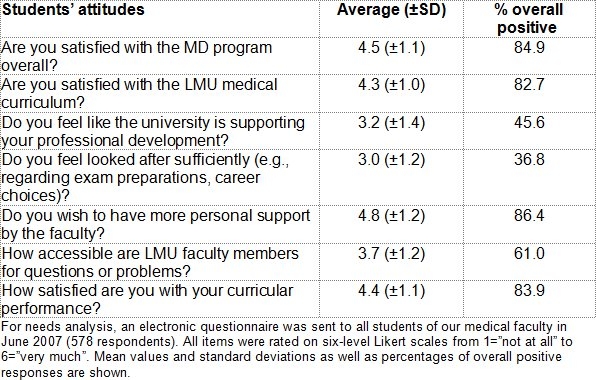

The web-based survey was composed of 7 scaled items (6-level Likert scale, ranging from “not at all” to “very much”, see Table 1 (Tab. 1)) and one free text question. Our aim was to gauge students’ desire for more individual support while asking respondents to differentiate this from the quality of medical education at our faculty. The voluntary survey was sent to all students enrolled in the MD program via e-mail (response rate = 14.1%, n=578). Respondents were spread across all years of our medical curriculum (n=141, 108, 80, 83, 85 and 80 for years 1-6, respectively). To avoid possible bias, the words “mentor” or “mentoring” were never used in the invitation for participation or the questionnaire itself.

Table 1. Analysis of the demand for mentoring among medical students at the LMU, Germany.

Focus groups

To further assess the need for mentoring and to specify the conceptual model of our mentoring program, we conducted four focus groups, two with medical students and two with faculty physicians with a total of 48 participants. Advanced students were mixed with students in their pre-clinical years. The same principle was applied for faculty physicians, who were recruited from different academic levels and specialties. Focus group discussions lasted between 67 and 83 minutes. Participants were informed that the data would be evaluated anonymously and be used for scientific purposes, particularly for implementing a mentoring program. We used open-ended questions which centered on the demand for mentoring among medical students, attitudes towards mentoring, and a possible mentoring program to be introduced at the faculty [18]. The focus group discussions were recorded, transcribed, and subsequently categorized by two investigators independently using grounded theory [19].

Sign-up survey

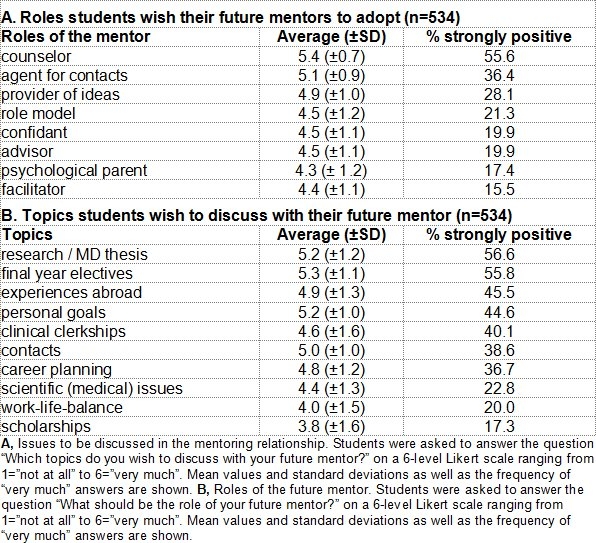

Students in the clinical semesters were informed through e-mail, presentations in lectures, web forums and word of mouth that they could participate in a one-to-one mentoring program. All students interested in one-to-one mentoring through our program were required to sign up on a specifically designed web site and complete an additional questionnaire addressing their expectations regarding the roles of their mentors, the mentoring relationships and suggestions for topics to be discussed with future mentors (n=534). Eligible for application were all students in clinical years (n=2.074). The survey was composed of 34 items with 6-level Likert scales, 3 multiple choice questions, and 8 free text items. Likert scale items were generated using the categories determined in qualitative analysis of focus groups.

Ethical considerations

The LMU ethics committee found no cause for concern in our research design and methods.

Results

Needs analysis

Desire for mentoring among medical students

In a survey performed among all medical students at the LMU medical school, 84.9% expressed overall satisfaction with the MD program, and 82.7% stated that they were satisfied with the teaching offered by the medical faculty (see Table 1 (Tab. 1)). However, more than half of the participants (54.4%) stated that the faculty did not foster their personal and professional development. Furthermore, 63.2% said they did not feel looked after sufficiently (e.g., regarding career planning and exam preparations). Additionally, 86.4% expressed a desire for more personal and individual support by the faculty.

Focus group analysis

The primary reason for conducting focus groups with medical students and physicians was to further explore their attitudes towards mentoring and to substantiate the conceptual model of a future mentoring program. Classifying the participants’ responses yielded four major topics:

(a) Mentoring experiences,

(b) needs and demand for mentoring,

(c) the role of the mentor, and

(d) the structure of a future mentoring program.

(a) Mentoring experiences

Only some physicians and few students had previously identified a mentor, who had supported them during their studies. In most of these cases the mentor was the supervisor of their MD thesis research. For example, one student pointed out: "In my experience, research advisors often take on a mentor's role. For me, my advisor is someone I can ask anything!“ Many of the students and physicians never had experienced mentoring in any form.

(b) Need and demand for mentoring

Faculty physicians unanimously supported a future mentoring program as evident in comments like "I would have loved to have a mentor when I was in medical school" or "That is precisely what I was missing during my studies." Students were also decidedly in favor of the idea of a mentoring program but more hesitant as some seemed weary of getting into more curricular commitments. The focus groups yielded a number of topics that students would like to discuss with a mentor. These include the choice of their MD thesis, career planning, job applications, and work-life-balance. Some physicians and students highlighted the issue of networking, such as "A mentor should be someone with insight who knows people, that is people the student can relate to."

(c) The role of the mentor

Students' and physicians' perceptions of the role of the mentor matched quite well. Responses of participants from all groups defined mentors as counselors, role models, providers of ideas, agents for contacts, confidants, precursors, or psychological parents. For instance, one student pointed out: "A mentor should be a kind of companion, a counselor if I have questions to ask, and a provider of ideas for issues for which I don't even know to ask the right questions."

(d) The structure of a future mentoring program

All four focus groups agreed that a mentoring program would impose additional workload on mentors. This is exemplified by comments like "A commitment to mentoring will likely be an additional burden for mentors. Therefore I think it is essential to limit the workload of mentors - and to make the program voluntary." Most students wanted the future mentoring program to be optional for mentors. "It certainly would not be a good idea to obligate physicians to serve as mentors, they have to enjoy the commitment and be motivated by themselves". Similarly, physicians favored a mentoring program that is voluntary but open to all students. Future mentors and mentees had to have the opportunity to change their mentor or mentee, if necessary. All groups agreed that they would benefit more from a long-lasting mentoring relationship. "I would prefer to keep the same mentor throughout my studies." There was agreement in all four groups that each mentor should not supervise more than a small number of mentees. Students emphasized the importance of one-to-one meetings between mentors and mentees. "You often have questions that you would not want to ask in a group."

Expectations of medical students signing up for the mentoring program

Students signing up for the one-to-one mentoring program were asked to define what they hope to be the role of their future mentor (see Table 2A (Tab. 2)). The results indicated that students "very much" wanted their mentors to act as counselors, expected their mentors to arrange contacts for them and provide ideas for their professional development. Topics future mentees “very much” wished to discuss with their mentors (see Table 2B (Tab. 2)) included MD thesis research, final year electives, experiences abroad, and personal goals.

Table 2. Roles of the mentor and topics to be discussed in the mentoring relationship.

The majority of students felt that one (23.0%) or two (47.0%) personal meetings per semester were the minimum requirement to sustain a mentoring relationship. However, two (30.5%) or three (32.2%) meetings per semester were estimated to be desirable. Students recommended that these meetings should last 20-30 (39.3%) or 30-45 minutes (41.6%). In addition to personal meetings favored by 98.5% of respondents, 89.5% thought that e-mail should be used as a means of communication between mentors and their mentees. On average, one mentor should oversee a maximum of 3 mentees (mean 3.4, SD 2.2).

Discussion

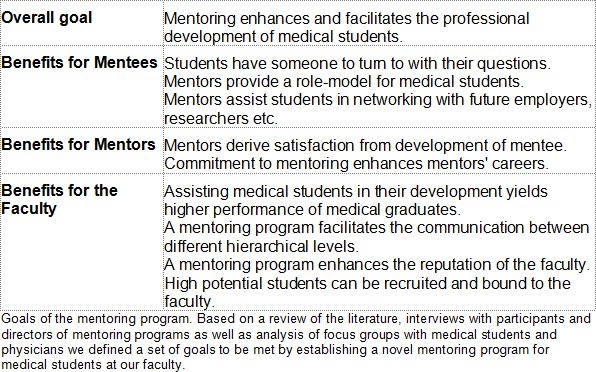

Definition of goals for a mentoring program

Based on our needs analysis and a review of the literature, we established a number of goals and expectations for a future mentoring program for medical students (see Table 3 (Tab. 3)). The overall goal was to enhance and facilitate the professional and personal development of medical students. This includes providing a mentor who is genuinely interested to assist the students whenever they have any questions [20]. Mentors should have a positive influence on the students’ careers. Ideally, students will find a role-model in their mentor that will actively help them define and achieve their goals during medical school. Also, mentoring should assist students in networking with researchers, faculty physicians, potential future employers and perhaps other mentees [11].

Table 3. Goals for establishing a mentoring program for medical students.

It also seems essential that mentors derive satisfaction from the personal relationship with the students while following and fostering their development. Awards for outstanding mentors will increase personal satisfaction and may be valuable for mentors’ advancement [21], [22], [23]. Furthermore, the mentoring program should be beneficial for the faculty in several ways. Medical graduates achieve a higher quality and performance through training and practice in self-reflection and career-planning. The medical school will gain reputation for offering integrated care for their students’ personal and professional advancement. Profound and beneficial communication between different hierarchical levels at the medical school will be increased. This way, faculty will be much more aware of possible problems in the curriculum or the concerns of individual students. Individual mentees with high potential can be more easily identified to be recruited by the faculty. Their level of motivation to stay with the university might be increased by the personal relationship they will have formed with individual faculty members [24].

Structural challenges for implementing a mentoring program at LMU Medical School

There are several potential obstacles for implementing a large-scale mentoring program at LMU medical school when compared to other institutions. In Germany, there is still a notable lack of awareness regarding the benefits of mentoring both among students and the faculty. Therefore, the mentoring program needs to establish a culture of mentoring at our institution. Secondly, the medical school of LMU is among the largest medical schools in Europe with over 800 students per year enrolled in pre-clinical years and around 450 in each clinical year. Most of the literature reviewed on mentoring at medical schools deals with much smaller programs. Individual matching of mentors and mentees through personal interviews, in-depth evaluations and profiling, as some other programs do, can hardly be performed at a large-scale institution like LMU. Finally, faculty physicians already bear an extremely high workload. Residents and faculty physicians are notoriously burdened with balancing patient care, research, and teaching responsibilities, which can impede recruitment even of highly motivated physicians as it will invariably demand additional time and effort.

Preliminary considerations and conceptual shape of the mentoring program

Studies have shown that randomly assigning students to so-called mentors has a very low probability of leading to a fruitful relationship [9]. Therefore, allowing free and voluntary formation of mentor-mentee pairs is preferable. However, lacking an established self-sustaining culture of mentoring, these relationships currently have to form spontaneously, which makes them voluntary and free – but rare. Our goal is to establish a mentoring program at our institution that will foster the formation of compatible mentor-mentee pairings. Mentees will always be able to freely choose their mentor, but we will facilitate their choice by offering a number of motivated and qualified mentors to them.

Given the great number of students entering the LMU medical program each year, there are not enough suitable faculty members to provide every student with one-to-one mentoring through faculty during the pre-clinical years. Many of the questions and problems first and second year students face can be best answered by those who have just recently experienced a similar situation. Advanced peers are likely to be able to give much more concrete advice to pre-clinical students than faculty members. Also, peers may feel more comfortable discussing personal topics with each other [25], [26]. In conclusion, it is desirable to establish a peer-mentoring program for first and second year students. A positive mentoring experience in the first years will motivate students to take full advantage of the one-to-one mentoring program. Based on these preliminary considerations, we developed a novel, two-tiered concept of a mentoring program for medical students at our faculty. This concept comprises a society model that offers peer-mentoring for first- and second-year students and a one-to-one mentoring program for students in their clinical years (see Figure 1 (Fig. 1)).

Figure 1. Conceptual shape of the mentoring program.

Peer-mentoring: The Society Model

In order to feasibly satisfy the need for individual care identified in pre-clinical semesters, we adopted a vertical advising program that integrates students and faculty of all stages of their medical training. We designed a pyramidal model of five societies which include pre-clinical and clinical students as well as resident physicians and faculty members. The society functions as a source of support especially for the pre-clinical students. The division into five societies was adopted from the grouping of students into five groups in the first year anatomy course taking advantage of a pre-existing structure. Every member of the society was asked to complete an online profile that includes their areas of interest and expertise and is accessible to all other members of the society. Thus, students looking for support for a specific concern can easily find and direct themselves to someone with the corresponding field of expertise. To further encourage personal exchange, the societies set up various events ranging from lectures and excursions to sports and cultural events. Furthermore, in every society twelve highly motivated students serve as junior mentors. They are the primary contact persons for all students in their society and are responsible for organizing their society’s social events.

The primary concerns of students in their pre-clinical years generally focus on learning strategies and preparation for the first state examination at the threshold to their clinical studies. Having passed this exam, interests diversify as students begin their orientation towards medical subspecialties and research areas. We have shown that these topics are among those that prospective mentees in their clinical years most urgently wish to discuss with their mentors (see Table 2B (Tab. 2)). The need for more individualized care as well as expertise in the subjects desired by the mentees has led us to conclude that one-to-one mentoring through physicians would most suit the needs of students in their clinical semesters.

One-to-one-mentoring

This part of the mentoring program provides all students in their clinical years with a mentor of their choice. These mentors are all volunteers, mostly physicians at LMU hospitals, yet also scientists, physicians from LMU-affiliated teaching hospitals and private practices. Students have two ways of choosing a mentor. Students can either directly ask any physician or researcher they know to become their mentor or choose through an online matching profile system. For the former type of choosing a mentor, the student simply signs up on the website to formalize this relationship. For the latter, which is more common, we have created a platform where volunteer prospective mentors as well as mentees can create online matching profiles which include scaled and multiple-choice items focusing on areas of interest and aspirations for the future as well as a free text. For any student searching for a mentor, an automated matching algorithm displays the ten most suitable mentors according to the matching profile. The students can then read these selected mentors’ free texts to ultimately decide their choice. Unless mentors explicitly wish otherwise, they will no longer be suggested to students after they have three mentees.

Part of the program includes at least one meeting in person soon after the matching process. The location as well as the frequency of further meetings is explicitly left up to the mentoring pair’s discretion. Subsequently, mentor and mentee agree on goals to achieve. If either party chooses to end this relationship, the student can re-match for the following semester.

Pilot study

The one-to-one mentoring was tested in a pilot study beginning in May, 2008 and involving 125 mentees. The society-based peer-mentoring was launched in October, 2008. Currently, 874 students from the pre-clinical years are distributed among five societies. Within these societies they can take advantage of the advice and expertise of 501 clinical students and 84 physicians. In the one-to-one mentoring program, 308 students in their clinical years are currently assigned to one of 137 physician mentors. Interestingly, while students close to their graduation might consider it to be too late to choose a mentor, 25.6% of the students in their first clinical year have a personal mentor indicating that the number of participants will significantly grow in the future. First evaluation results are currently being analyzed and will be published soon.

Conclusions

In contrast to medical education in the U.S. and the UK, mentoring programs in academic medicine are only beginning to develop in Germany. In the present study we have identified a profound desire for mentoring among medical students. Particularly, students are looking for a mentor who can help them in areas like research, final year electives and experiences abroad. Also, students hope to be provided by their mentors with ideas and contacts for their professional development.

The very large number of students at institutions like LMU Munich poses a serious challenge to the feasibility of an individualized mentoring program for medical students. To overcome this obstacle, we developed a novel two-tiered system that limits one-to-one mentoring to students in their clinical years but offers a society-based peer mentoring for pre-clinical students. Also, the large number of students requires an automated matching process. However, free choice of mentors by the mentees is essential for successful mentoring relationships. Therefore, we developed an electronic matching algorithm which proposes best-matching mentors to mentees based on online matching profiles. Students then actively choose a mentor from these profiles.

Providing more than 4,000 medical students in one medical school with a personal mentor may seem daunting, if not impossible. However, our proposed two-tiered system provides evidence that a well-organized mentoring program is feasible to implement in medical schools with large number of students. By using an adaptive online matching process and automated evaluation mechanisms we have eliminated administrative overhead in the one-to-one mentoring program. Formation of individual mentoring relationships is student-driven and efficient. Similarly, the peer mentoring concept makes the many competencies and experiences that already exist among medical students searchable and accessible for fellow students.

In conclusion, through a needs assessment we have identified a strong need for mentoring among medical students and developed a novel mentoring approach. The concept seems particularly well-suited for large communities and can serve as a model for implementing mentoring programs at other large-scale educational institutions.

Note on contributors

Philip von der Borch, MD, Kostantinos Dimitriadis, MD, and Sylvère Störmann, MD, are the principal coordinators of the mentoring program MeCuM-Mentor at the LMU Faculty of Medicine in Munich, Germany. Felix G. Meinel and Stefan Moder are medical students participating in the coordination and scientific evaluation of the program. Martin Reincke, MD, is Clinical Teaching Dean of the Medical Faculty and Director of the Department of Medicine at the LMU, Munich, Germany. Ara Tekian, PhD, MHPE, is Associate Professor of medical education and Associate Dean for International Affairs at the College of Medicine, the University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, USA. Martin R. Fischer, MD, MME, is the Director of the Institute for Didactics and Educational Research in Health Sciences at the Witten/Herdecke University in Witten, Germany.

Acknowledgements

The initial conception of a possible mentoring program for medical students at the LMU medical school was outlined by the participants of the LMU Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine Exchange Program 2007. The authors would like to thank their fellow participants Dorothea Greiner, Simon Hohenester, Simon Mucha and Hanno Niess as well as the program's coordinator Dr. Carolin Sonne.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Collins EG, Scott P. Everyone who makes it has a mentor. Harv Bus Rev. 1978;56:89–101. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray J, Armstrong P. Academic health leadership: looking to the future. Proceedings of a workshop held at the Canadian Institute of Academic Medicine meeting Quebec, Que., Canada, Apr. 25 and 26, 2003. Clin Invest Med. 2003 Dec;26(6):315–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeAngelis CD. Professors not professing. JAMA. 2004;292(9):1060–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.9.1060. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.9.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. Jama. 2006;296(9):1103–1115. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1103. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.9.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reynolds HY. In choosing a research health career, mentoring is essential. Lung. 2008;186(1):1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00408-007-9050-x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00408-007-9050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berk RA, Berg J, Mortimer R, Walton-Moss B, Yeo TP. Measuring the effectiveness of faculty mentoring relationships. Acad Med. 2005;80(1):66–71. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200501000-00017. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200501000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buddeberg-Fischer B, Herta KD. Formal mentoring programmes for medical students and doctors--a review of the Medline literature. Med Teach. 2006;28(3):248–257. doi: 10.1080/01421590500313043. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590500313043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buddeberg-Fischer B, Stamm M, Buddeberg C. Academic career in medicine: requirements and conditions for successful advancement in Switzerland. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:70. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-70. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-9-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wakeford R, Lyon J, Evered D, Saunders N. Where do medically qualified researchers come from? Lancet. 19853;2(8449):262–265. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ackson VA, Palepu A, Szalacha L, Caswell C, Carr PL, Inui T. "Having the right chemistry": a qualitative study of mentoring in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78(3):328–334. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200303000-00020. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200303000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aagaard EM, Hauer KE. A cross-sectional descriptive study of mentoring relationships formed by medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(4):298–302. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20334.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tekian A, Jalovecky MJ, Hruska L. The impact of mentoring and advising at-risk underrepresented minority students on medical school performance. Acad Med. 2001;76(12):1264. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200112000-00024. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200112000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Straus SE, Chatur F, Taylor M. Issues in the mentor-mentee relationship in academic medicine: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2009;84(1):135–139. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819301ab. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819301ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Sullivan PS, Niehaus B, Lockspeiser TM, Irby DM. Becoming an academic doctor: perceptions of scholarly careers. Med Educ. 2009;43(4):335–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03270.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woessner R, Honold M, Stehr SN, Steudel WI. Support and faculty mentoring programmes for medical students in Germany, Switzerland and Austria. Med Educ. 2000;34(6):480–482. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00406.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freeman R. Faculty mentoring programmes. Med Educ. 2000;34(7):507–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paice E, Heard S, Moss F. How important are role models in making good doctors? BMJ. 2002;325(7366):707–710. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7366.707. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7366.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halcomb EJ, Gholizadeh L, DiGiacomo M, Phillips J, Davidson PM. Literature review: considerations in undertaking focus group research with culturally and linguistically diverse groups. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(6):1000–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01760.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glaser BGSA. Discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research. Mill Valley,/CA(USA): Sociology Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhagia J, Tinsley JA. The mentoring partnership. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75(5):535–537. doi: 10.4065/75.5.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman R. Towards effective mentoring in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1997;47(420):457–460. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose GL, Rukstalis MR, Schuckit MA. Informal mentoring between faculty and medical students. Acad Med. 2005;80(4):344–348. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200504000-00007. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200504000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pololi L, Knight S. Mentoring faculty in academic medicine. A new paradigm? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):866–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.05007.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.05007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benson CA, Morahan PS, Sachdeva AK, Richman RC. Effective faculty preceptoring and mentoring during reorganization of an academic medical center. Med Teach. 2002;24(5):550–557. doi: 10.1080/0142159021000002612. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0142159021000002612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bussey-Jones J, Bernstein L, Higgins S, Malebranche D, Paranjape A, Genao I, Lee B, Branch W. Repaving the road to academic success: the IMeRGE approach to peer mentoring. Acad Med. 2006;81(7):674–679. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000232425.27041.88. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000232425.27041.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pololi LH, Knight SM, Dennis K, Frankel RM. Helping medical school faculty realize their dreams: an innovative, collaborative mentoring program. Acad Med. 2002;77(5):377–384. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200205000-00005. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]