Abstract

Background: Future physicians should be educated in evidence-based medicine. So it is of growing importance for medical students to acquire both practical medical and basic research competencies. However, possibilities and concepts focusing on the acquisition of basic practical research competencies during undergraduate medical studies in Germany are rare. Therefore the aim of this article is to develop a didactic and methodological concept for research-based teaching and learning based on the initial results from the block placement in general practice.

Methods: Connecting medical didactic approaches with classic educational control measures (knowledge, acceptance and transfer evaluation, process evaluation, and outcome evaluation).

Results: We describe the steps for implementing a research task into the block placement in general practice. Also stressed is the need to develop didactic material and the introduction of structural changes. Furthermore, these steps are integrated with the individual educational control measures. A summary serves to illustrate the learning and teaching concept (Block Placement Plus).

Conclusion: The conceptualisation of the Block Placement Plus leads to changes in the daily life routine of medical education during the undergraduate block placement in general practice. The concept can in principle be transferred to other courses. It may serve as an instrument for teachers within the framework of a longitudinal curriculum for the scientific qualification of medical students.

Keywords: research competencies, undergraduate medical education, general practice

Abstract

Hintergrund: Zukünftige Ärzte sollen zu Evidenz-basierter Medizin (EbM) ausgebildet werden. Deswegen ist neben der Ausbildung von medizinischen Kompetenzen auch zunehmend eine wissenschaftliche Basisausbildung wichtig. Möglichkeiten und Konzepte, die auf die Entwicklung von Forschungskompetenzen und wissenschaftlicher Qualifizierung von Studierenden abzielen, sind jedoch bisher spärlich. Ziel des vorliegenden Artikels ist es, aus ersten Erfahrungen im Blockpraktikum Allgemeinmedizin ein didaktisch-methodologisches Konzept abzuleiten für forschungsorientiertes Lernen und Lehren.

Methoden: Verknüpfung von Bausteinen medizin-didaktischer Methodologie mit jenen des klassischen Bildungscontrolling (Wissens-, Akzeptanz- und Transferevaluation, Prozessevaluation und Ergebnisevaluation).

Ergebnisse: Vorgestellt werden die Schritte zur Implementierung einer Forschungsaufgabe in das Blockpraktikum. Gleichzeitig wird auf die Notwendigkeit der Entwicklung von lehrdidaktischem Material und der Einführung von strukturellen Veränderungen abgehoben. Des Weiteren findet die Verzahnung mit den einzelnen Bildungscontrolling-Schritten statt. Eine Übersicht dient der Veranschaulichung des Lehr- und Lernkonzepts (Blockpraktikum plus).

Schlussfolgerung: Die Konzeptionalisierung des „Blockpraktikum plus“ in Allgemeinmedizin stellt eine Veränderung des Lehr- und Lernalltags dar. Das Konzept ist prinzipiell übertragbar auf andere Lehrveranstaltungen und kann als Instrument für Lehrende im Rahmen einer longitudinalen Kompetenzvermittlung wissenschaftlicher Basisfertigkeiten eingesetzt werden.

Introduction

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) as a fundamental thought concept and strategic concept is increasingly recognised. Thus there is a need to train future physician in EBM. As a result, apart from training in medical competences basic training in scientific skills is gaining in importance. Opportunities and concepts aimed at the development of research skills and academic qualifications of students have been rare to date [1], in spite of students indeed seeing the benefits and the need for scientific training during their studies [1], [2] as it forms the basis for critical evaluation of studies and their result within a framework of individualised, patient-centred health care provision.

The achievement of scientific qualifications by students can be promoted through special, practice-related research tasks [3]. By dealing with such concrete research tasks, students learn scientific working methods and technical knowledge at the same time [4]. Currently such approaches are not used to date in medical education in Germany in contrast to other countries [5], [6], [7] although they can represent a typical win-win situation for everyone involved: Students gain scientific skills and general practitioners (GPs) or health care researchers acquire practice-related data. But such a win-win situation is only the case if both scientific-methodological and didactic aspects are taken into account [8].

Against this background, the aim of this article is to derive a didactic-methodological concept based on the initial experiences with the involvement of students in scientific data collection during their block placement in general practice at the University of Tübingen. This concept will describe research-based learning and teaching in the block placement in general practice and be transferable.

Methods

Setting

During their 10th semester, students at the University of Tübingen absolve a two-week block placement in general practice with GPs. Each semester approx. 140 students take their placements spread over approx. 200 GPs. All 140 students in the Winter Semester 2008 were prepared for their placements and their new tasks within it in an approx. 2 hour introductory seminar on the block placement in about twelve roughly equally sized groups. The semesters were led by six lecturing physician (in GP) who have long term experience with teaching at tertiary level. The seminar leaders were previously instructed by the Division of General Practice regarding the student introduction and information to the pilot in a group seminar lasting approx. 1 hour.

The ethics commission passed a positive vote on the pilot project.

The research topic was picked from the vaccination domain as GPs play a central role in it. Students were to determine the vaccination status using two questionnaires,

based on information by the patient (Questionnaire 1) and

based on the office documentation database (office files) (Questionnaire 2)

At 84%, student acceptance of participation in this project was high. It was seen that students were capable of carrying out the first of the two tasks, gathering data from the patients. This was manifest in the almost seamless documentation of the questionnaires. We are pleased to note that the data gathered by the students was published in a scientific publication [9], [10]. The second task which involved having to deduct the current vaccination status based on the office documentation database resulted in gaps in the questionnaires and much missing data (depending on the vaccination, up to 80% of the data was missing). However, the answer options for this question had been dichotomised (i.e. is the patient currently vaccinated Yes/No) with no answer option of Unknown. It would therefore appear that in spite of the planned support by medical staff in evaluation the office documentation database the evaluation of the vaccination status could not be carried out fully. Students were also for the first time confronted with the documentation software used by GPs.

It was not possible to apply additional data on the evaluation of the learning effect regarding empirical research as the pilot had placed emphasis on the two outcomes stated above.

Approach to Deriving the Teaching and Learning Concept

Along the lines of the first results and problem analyses of the pilot project in the sense of “lessons learnt" the overall concept of a block placement which includes scientific training of students through dealing with research tasks is to be derived.

The principle of Constructive Alignment combines self-managed learning of students with the role of relevant (study) tasks. The task is therefore the creation of a learning environment in which students can achieve the desired learning goals (working scientifically) using relevant and realistic tasks [3]. There is a connection with the classic educational evaluation steps (EES) of knowledge, acceptance and transfer evaluation, process evaluation and results evaluation as building blocks in the development of the learning concept presented here [11]. In the present case process evaluation will be carried out at the level of a research task and the level of overall curricular activity (see 4a and 4b below). This permits the integration of scientific methodological and didactic questions. The methodological approach used here aims to lead to scientific knowledge, scientific qualification and the increase of decision-making skills in students [12].

In the following, the educational evaluation steps will be specified:

1. Knowledge check following preparatory teaching on technical knowledge and methods

The students receive specific methodological-didactic and technical preparation for the research tasks in preparatory teaching and are tested for such knowledge.

The central question is: "Do the students have the technical and methodological knowledge for the research task?”

2. Acceptance control amongst students and teaching staff

All teaching physicians are to be informed prior to the event about the plans (for example at an information event). To increase the acceptance the research question should be developed by the project planners with input from the teaching physicians. The people affected are thereby included in the development process.

Students are prepared for their trainee placement in the introductory teaching events. Here it is important to stress the opportunity for learning when dealing with the research question.

The central question is: “Is the research topic, the work effort required and the tutoring effort required being accepted?”

3. Transfer control on site when working on the research question regarding the application of technical knowledge and methods

Teaching physician observe the students on site to see if they correctly apply what they have learned in the introductory teaching. For example it will be evaluated if it is possible to have students correctly conduct the questioning of a patient using questionnaires.

The central question is: “Are the technical knowledge and the methods being used correctly?”

4a. Process control regarding the research task

The data collected by the students is to be usable for scientific purposes. This usage combination should not be the sole emphasis of the concept but equally allow learning processes regarding empirical research (and patient-centred GP-based healthcare) to be in the focus.

The central questions are: “Is the research process free of selection and information bias?” and “Is this process being controlled for potential interference (confounders)?” “Are the students developing the stated competencies?”

4b. Process control regarding the overall curricular activities

The central question is: “Is the integration of the research task into the overall activities working?”

5. Results control

The learning goals must be made clear in relation to the research tasks and operationalised for the degree of their achievement to be measurable (e.g. increase of solution and decision making skills regarding problems in a GP office or increase of technical knowledge). This can, for example, be done through before-and-after type questioning.

The central question is: “Have the students developed the stated technical and social skills?”

Results

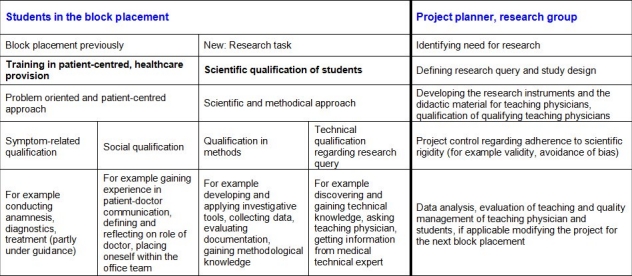

In the following the steps for implementing the research task into the block placement are presented. At the same time it is explained, which didactic materials need to be developed for learning and which structural changes need to be introduced. The integration with the individual education evaluation steps is also illustrated (knowledge, acceptance, transfer, process and results control). Block Placement Plus, see Table 1 (Tab. 1). Table 2 (Tab. 2) shows the pilot project structure.

Table 1. Who does what how (v)? – Concept of the Block Placement Plus*.

Table 2. Overview over the teaching and learning concept on scientific qualification of students in the block placement in general practice.

Discussion and Conclusion

The aim of the present endeavour was to further develop a learning and teaching concept based on the initial experiences of the pilot project to enable students to gain medical qualifications through dealing with a research topic in their block placement in general practice (Block Placement Plus). This was based on classic education evaluation steps. The participation of students in research processes can be seen as an essential step in further developing the culture of evidence-based medicine [13].

However, conducting the Block Placement Plus brings additional (organisational) work effort for all participants (students, teaching staff, teaching GPs). In addition, for each new research task appropriate material (for teaching, knowledge and transfer controls, data collection etc, see Table 1 (Tab. 1)) must be developed.

The general concept presented here places its main emphasis on the compatibility of the research query and the competence areas that are to be developed. For example, if the research query was "Based on the GPs documentation database (office files), is there vaccination coverage?” then the competence area that is to be developed by the students would be “Evaluate and decide if vaccination cover is or is not present” (decision making or judgement competence [14]). In addition it is clear that by implementing a research task technical social competencies (for example finding your position within the GP’s routine, communicating with the technical staff, communicating with patients when collecting data) can also be developed. In doing so it is important that these competencies are specified, defined and checked depending on the type of research task. The definition of exact target variables, avoiding information or selection bias or accounting for disturbances (confounders) must be borne in mind. Following the principle of communicative validation, the research question is defined in a dialogical process by the involved teaching physicians, students and researchers. The ability to bring their own queries to the process, teaching physicians and students are involved in the research process from the beginning, increases the acceptance of such projects [15]. This aspect of the process itself can already develop social and technical competencies.

Challenges and approaches to the Optimisation of the Implementation of the Block Placement Plus

Because implementation is highly dependent on the support of the teaching physicians, it is important that they are well informed beforehand and integrated into the process. Some teaching physicians felt they had been left out in the pilot, amongst other reasons because they had not been included in the development of the problem or the research task. This will be improved in future.

Because the pilot project involved the collection of sensitive, internal GPs’ data (digital documentation of the vaccination status), some teaching physicians felt that they were being checked. Such potential problem areas should be brought up and clarified early.

Another challenge was the transfer control within the GPs’ office, i.e. controlling if the research task was being handled “correctly”. In future, medical technical staff could also be included in the planning, something that was not or not sufficiently done in the pilot.

In summary, the following measures are important for the implementation into daily routines:

Informing teaching physicians in time and sufficiently about the plans (for example as part of regular didactic events each semester).

Preparing all students of the block placement for their new tasks (for example in an introductory seminar for the block placement, including the preliminary test).

Checking correct conduct of the new tasks and collecting the data in the office (for example through transfer control instruments or through the teaching physicians).

Checking the acquisition of competencies (for example feedback in a final seminar or second part of a before-and-after test)

Evaluation and further processing of data material and its presentation (for example in workshops).

The expanded block placement in general practice (Block Placement Plus) brings substantial change to the daily routine of teaching and learning. In principle, the model can be transferred to other placements in medicine and can be used as an instrument for teaching staff with the framework of longitudinal competence transfer in basic scientific skills. An adequate time frame for dealing with the research task is important so the clinical training does not slip into the background.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Murdoch-Eaton D, Drewery S, Elton S, Emmerson C, Marshall M, Smith J, Stark P, Whittle S. What do medical students understand by research and research skills? Identifying research opportunities within undergraduate projects. Med Teach. 2010;32(3):e152–e160. doi: 10.3109/01421591003657493. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01421591003657493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hren D, Lukic IK, Marusic A, Vodopivec I, Vujaklija A, Hrabak M, Marusic M. Teaching research methodology in medical schools: students' attitudes towards and knowledge about science. Med Educ. 2004;38(1):81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01735.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biggs J, Tang C. Teaching for Quality Learning at University. 3rd edition ed. Berkshire/England: Open University Press, McGraw-Hill Education, McGraw-Hill House; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atteslander P. Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung. Berlin, New York: de Gruyter; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallis AB, Chereches R, Oprescu F, Brinzaniuc A, Dungy CI. An international model for staffing maternal and child health research: the use of undergraduate students. Breastfeed Med. 2007;2(3):139–144. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2006.0036. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2006.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magzoub M, Schmidt H. A taxonomy of community-based medical education. Acad Med. 2000;75(7):699–707. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200007000-00011. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200007000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt H, Neufeld V, Nooman Z, Ogunbode T. Network of community-oriented educational institutions for the health sciences. Acad Med. 1991;66(5):259–263. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199105000-00004. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199105000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kern D, Thomas P, Howard D. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach. 2nd ed. Baltimore/United States: The John Hopkins University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mosshammer D, Muche R, Hermes J, Zollner I, Lorenz G. Factors associated with influenza vaccination information--a cross-sectional study in elderly primary care patients. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2009;103(7):445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moßhammer D, Lorenz G. Eine Querschnittuntersuchung über die Angaben älterer hausärztlicher Patienten zu ihrem Impfschutz. Monitor Versorgungsforsch. 2009;5:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pohlenz P. Lehrevaluation und Qualitätsmanagement. SuB. 2008;1:66–78. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kronenthaler A. Zur Entwicklung interkultureller Handlungskompetenz. Landau: Verlag Empirische Pädagogik; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metcalfe D. Involving medical students in research. J Royal Soc Med. 2008;101(3):102–103. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2008.070393. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2008.070393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauer-Klebl A, Euler D, Hahn A. Förderung sozial-kommunikativer Handlungskompetenz durch spezifische Ausprägung dialogorientierter Lehrgespräche, in Lehren und Lernen in der beruflichen Erstausbildung. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag; 2001. pp. 163–186. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bohnsack R. Rekonstruktive Sozialforschung. Einführung in Methodologie und Praxis qualitativer Forschung. Einführung in Methodologie und Praxis qualitativer Forschung. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chien A, Coker T, Choi Lea. What do pediatric primary care providers think are important research questions? A perspective from PROS providers. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6(6):352–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.07.002. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ambp.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller G. Assessment of clinical skills/Competence/Performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9):63–67. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kremer H, Melke K, Sloane P. Fächer- und Lernortübergreifender Unterricht - Maßnahmen zur Förderung beruflicher Handlungskompetenz, in Lehren und Lernen in der beruflichen Erstausbildung. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag; 2001. pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stark R, Gruber H, Hinkofer L, Mandel H, Renkel A. Entwicklung und Optimierung eines beispielbasierten Instruktionsansatzes zur Überwindung von Problemen der Wissensanwendung, in Lehren und Lernen in der beruflichen Erstausbildung. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag; 2001. pp. 369–387. [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeMaria AN. How do I get a paper accepted? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(15):1666–1667. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.017. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eldridge S. Good practice in statistical reporting for Family Practice. Fam Pract. 2007;24(2):93–94. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmm010. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmm010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothwell PM, Bhatia M. Reporting of observational studies. BMJ;335(7624):783–784. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39351.581366.BE. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39351.581366.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]