Abstract

During corticogenesis, pyramidal neurons (~80% of cortical neurons) arise from the ventricular zone (VZ) pass through a multipolar stage to become bipolar and attach to radial glia1, 3, and then migrate to their proper position within the cortex1, 2. As pyramidal neurons migrate radially, they remain attached to their glial substrate as they pass through the subventricular (SVZ) and intermediate (IZ) zones, regions rich in tangentially migrating interneurons and axon fiber tracts. We examined the role of Lamellipodin (Lpd), a homolog of a key regulator of neuronal migration and polarization in C. elegans, in corticogenesis. Lpd depletion caused bipolar pyramidal neurons to adopt a tangential, rather than radial-glial, migration mode without affecting cell fate. Mechanistically, Lpd depletion reduced the activity of SRF, a transcription factor regulated by changes in the ratio of polymerized to unpolymerized actin. Therefore, Lpd depletion exposes a role for SRF in directing pyramidal neurons to select a radial migration pathway along glia rather than a tangential migration mode.

Lpd is a member of the MIG-10/RIAM/Lpd (MRL) protein family that links signaling from Ras superfamily proteins and phosphoinositides to actin dynamics and cell adhesion during polarization and migration 4–7. The C. elegans MRL ortholog, MIG-10, has important roles in neuronal migration, polarization, and axon guidance 8–11. As Lpd is expressed uniformly throughout the cortex during embryonic development (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1a,b), we hypothesized that Lpd may function in multiple aspects of cortical development. We used in utero electroporation to transfect cortical progenitor cells and manipulate Lpd function. E14.5 mouse embryos were co-electroporated with plasmids encoding mCherry (to mark electroporated cells) and a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) vector that knocked down Lpd expression efficiently (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1c). Analysis of transfected neurons at E18.5 revealed that cells expressing Lpd shRNA accumulated aberrantly within the SVZ and IZ (Fig. 1a) compared to control cells expressing a random sequence shRNA construct, suggesting that Lpd depletion impairs migration of neurons to the superficial cortical layers.

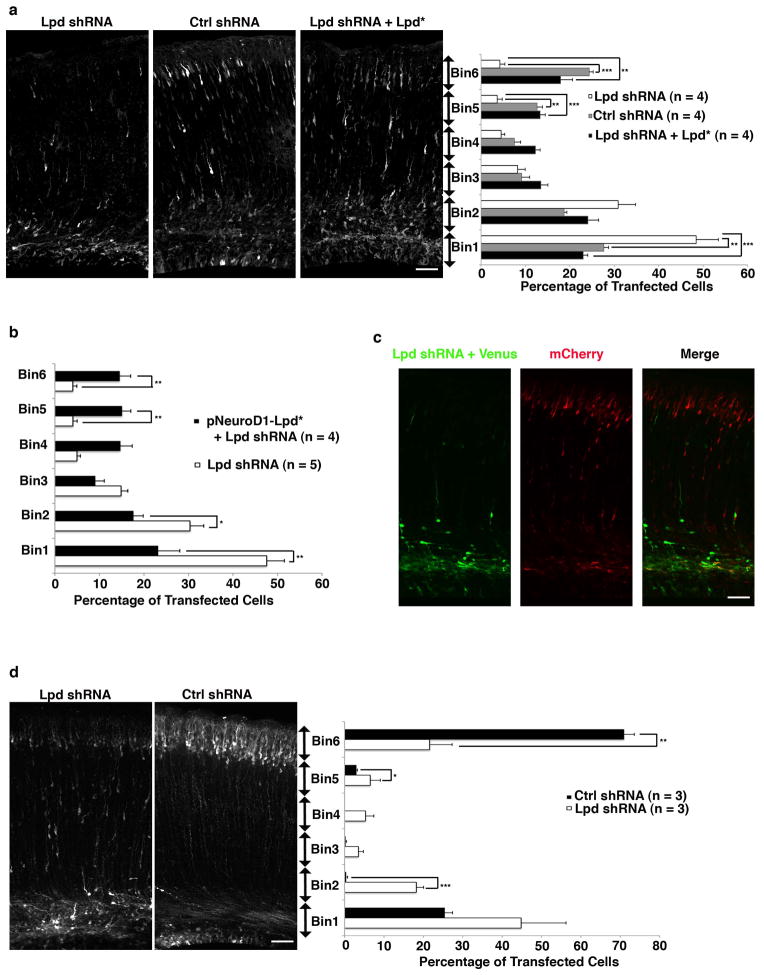

Figure 1. Lpd silencing impairs neuronal positioning.

(a–d) Mouse embryos were electroporated in utero at E14.5 and harvested at E18.5 (a, b, c) or P3 (d). (a) Quantification of cell distribution in cortical sections co-electroporated with mCherry and either Lpd shRNA, control (Ctrl) shRNA, or Lpd shRNA + Lpd rescue construct (Lpd*)(** p <0.01, *** p <0.001, one-way ANOVA, n = 4 brains per condition). (b) Rescue of the shRNA-mediated phenotype with an RNAi-resistant Lpd construct (Lpd*) expressed under the NeuroD1 promoter (* p <0.05, ** p <0.01, Student’s t-test, n = 4–5 brains per condition). (c) Images of a sequential electroporation of an embryo at E13.5 with Lpd shRNA plus Venus and subsequently at E14.5 with mCherry. (d) Distribution of cells at P3 after electroporation at E 14.5 (* p <0.05, **p <0.01, *** p <0.001, Student’s t-test, n = 3 brains per condition). Scale bars: 50 μm (a,b,c). Bar graphs are plotted as mean ± SEM.

To ensure the specificity of the cell positioning phenotype for Lpd, two additional Lpd shRNA vectors targeting different regions of Lpd (Data not shown) were electroporated and found to yield similar phenotypes. A rescue assay in which an RNAi resistant Lpd cDNA (by virtue of silent mutations) was co-electroporated with the Lpd shRNA restored normal neuronal positioning, confirmed that the phenotype was Lpd-dependent and not from off-target effects (Figs. 1a and S1d).

To determine whether the positioning phenotype resulted from an intrinsic defect in migrating neurons, we expressed shRNA-resistant Lpd selectively in post-mitotic neurons within the developing cortex using the NeuroD1 promoter 12, 13 (pNeuroD1-Lpd) and found that it rescued the Lpd knockdown positioning phenotype (Fig. 1b). In a separate test for cell autonomy of the phenotype, embryos were electroporated sequentially: at E13.5 with Lpd shRNA and Venus marker and again at E14.5 with an mCherry marker alone. As expected, the Venus expressing cells exhibited the positioning defect while the mCherry expressing cells were positioned normally (Fig. 1c). The morphology of radial glia (by Nestin staining) in transfected regions appeared normal (Supplementary Information Fig. S2), indicating that the Lpd phenotype was likely independent of defects in radial glial processes. In addition, levels of activated Caspase-3, an apoptotic marker, were unaffected by Lpd depletion, indicating that increased cell death did not contribute to the phenotype (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3).

The Lpd shRNA-mediated positioning defect could result from reduced speed of radial migration and/or failure of neurons to exit the SVZ/lower IZ. By time-lapse imaging of organotypic cortical slice cultures prepared from electroporated mouse embryos we found that the small fraction of Lpd shRNA-expressing bipolar neurons that reached the IZ and CP exhibited radial migration rates (9.1 ± 0.75 um/hr, mean±SEM; n = 44) similar to control (7.7 ± 0.44 um/hr; n = 73) (p> 0.05; Student’s t-test) and to rates observed previously for radial bipolar cells (Fig. S4a) 14. Therefore, Lpd depletion does not affect the migration speed of bipolar neurons that reach the upper IZ and CP. Interestingly, many Lpd-depleted neurons had failed to reach their terminal destination in the CP even when postnatal pups were examined (Fig. 1d and Supplemental Information Fig. S4b). Therefore, the Lpd depletion phenotype arises primarily from impaired exit of bipolar neurons from the SVZ/lower IZ rather than a delay in radial migration.

We next analyzed the morphology of Lpd knockdown cells aberrantly positioned within the SVZ and lower IZ. Normally, cortical pyramidal neurons transition from multipolar to bipolar morphology in the SVZ/IZ before entering the cortical plate via radial migration15; defects in the stereotypical shift to bipolar morphology might perturb radial migration. Interestingly, Lpd knockdown increased the frequency of bipolar cell morphology compared to control (Lpd shRNA: 82.8% ± 3.0%; n = 3 embryos; Control shRNA: 48.85% ± 4.2%; n = 3 embryos; electroporation at E14.5, analysis at E18.5) (Fig. 2a). Surprisingly, many bipolar cells expressing Lpd shRNA were oriented tangentially as judged by the angle of their leading process with respect to the pial surface (Fig. 2b,c) and appeared parallel to axon fiber tracts in the IZ/SVZ (Fig. 2d). Quantification of the average angle of the leading process of these cells and adjacent radial glia fibers confirmed this abnormal tangential orientation (Fig. 2e). Many Lpd depleted/tangentially oriented bipolar pyramidal neurons were observed at a significant distance from electroporated regions (Fig. 3a); similar phenotypes were observed after electroporation at both early and late stages of cortical development. Therefore, we hypothesized that Lpd inactivation caused pyramidal cortical neurons to migrate tangentially instead of radially along glia. We imaged organotypic cortical slice cultures prepared from E13.5 embryos (electroporated at E11.5) by time-lapse microscopy and observed that all Lpd-depleted bipolar tangential neurons were perpendicular to the radial glial processes and migrated with an average velocity of 10.5 ± 3.4 μm/h (mean±SEM, n = 37) (Fig 3b, Supplemental Videos 1a and 1b); tangential movement was not observed in control experiments. Interestingly, the average speed of tangentially migrating Lpd-depleted neurons more closely resembled the rates of radially migrating pyramidal neurons than tangentially migrating interneurons 14, 15.

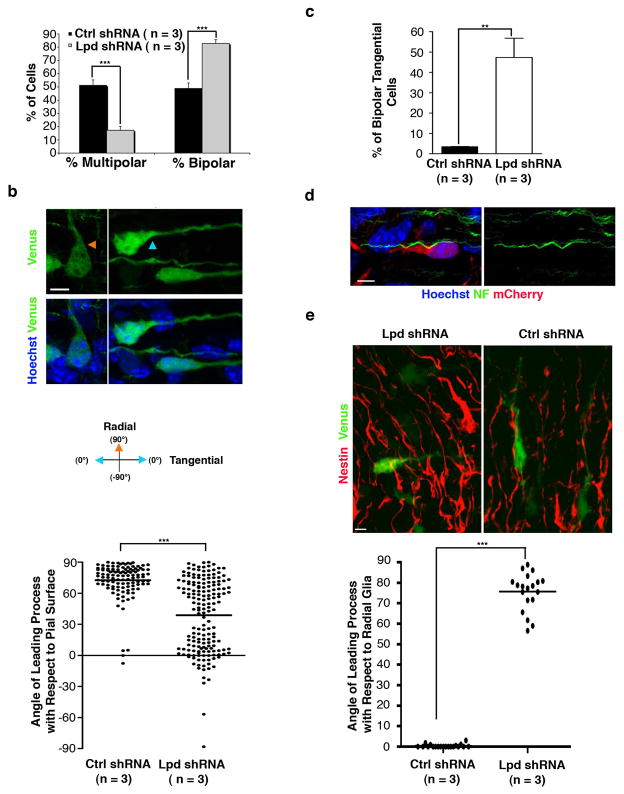

Figure 2. Suppression of Lpd increases the number of tangentially oriented bipolar pyramidal neurons in the IZ/SVZ.

(a–e) Mouse embryos were electroporated in utero at E14.5 and harvested at E18.5. (a) Percentage of multipolar versus bipolar cells in the SVZ and lower IZ of brains electroporated with either control (Ctrl) or Lpd. (b) Orientation of control (orange arrowhead) and Lpd shRNA (blue arrowhead) bipolar cells that co-express Venus in the SVZ/IZ. The graph represents the distribution of bipolar cells based upon the angle of their leading process with respect to the pial surface (90°) or ventricular surface (−90°). Cells were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 dye to visualize nuclei (blue). (c) Percentage of Lpd shRNA or control bipolar cells that are tangentially oriented in the IZ/SVZ (leading process angles between 30° and −30°). (d) Image of a tangentially oriented bipolar cell expressing Lpd shRNA identified by mCherry expression (red) in brain sections immunostained with axon fiber tract marker Neurofilament (green). (e) Tangential cells expressing Lpd shRNA do not align with radial glial fibers. The angle of the leading process of the tangential (as determined in (c)) Lpd shRNA-expressing cells was measured with respect to the radial glial fibers (identified by the expression of Nestin) and compared to that of bipolar control cells. Scale bars: 5 μm in (b), (d) and (e). Bar graphs are plotted as mean ± SEM (**p <0.01, *** p <0.001, Student’s t-test, n = 3 brains per condition).

Figure 3. Lpd depleted bipolar pyramidal neurons migrate tangentially within the IZ/SVZ but do not exhibit a change in cell fate.

(a) E18.5 cortical sections electroporated at E14.5 with Lpd shRNA and Venus. Cells were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 dye to visualize nuclei (blue). Enlargement of boxed region is shown below. The distance between the cell body of individual tangential cells and the border of the electroporated region is indicated (arrows). (b) Time-lapse of a tangentially oriented bipolar cell migrating in the IZ/SVZ (arrowhead). (c) Image of a tangentially oriented bipolar cell, co-electroporated with Lpd shRNA and Venus, that expressed the neuronal marker, Cux1 (red). Nuclei were visualized with Hoechst 33342 dye. Cortical neurons expressing Lpd shRNA and Venus (arrowheads) lack detectable (d) GABA expression (red), and (e) CXCR4 (red) expressed by migrating interneurons (arrow). (f) Orientation of the leading process of Lpd-depleted tangentially oriented bipolar cells in the medial, mediolateral, and lateral regions of the cortex. Brains were electroporated at E11.5 and harvested 37 hrs later. Bar graphs are plotted as mean ± SEM. Scale bars: 50 μm (a), 40 μm (b) 5 μm (c), and 10 μm (d) and 10μm (e).

To determine whether Lpd depletion induced the tangential migration phenotype by a partial or complete change in the fate of pyramidal neurons to interneurons, which normally migrate tangentially through the IZ/SVZ, we immunostained Lpd knockdown neurons for markers that distinguish between those neuronal types. Tangentially oriented Lpd knockdown cells expressed Cux1 (Fig. 3c), but not GABA (Fig. 3d), indicating that they remained cortical pyramidal neurons and had not converted into tangentially migrating interneurons. Tangentially migrating interneurons within the SVZ must express CXCR4 chemokine receptor 16, 17 to prevent their premature entry into the cortical plate and subsequent radial migration. We reasoned that upregulation of CXCR4 in Lpd knockdown neurons might cause their tangential migration phenotype, however, the tangentially oriented Lpd-knockdown neurons lacked detectable CXCR4(Fig. 3e). Together these data indicate that bipolar pyramidal cortical neurons, which normally utilize a radial gliophilic pathway, migrate tangentially in the IZ/SVZ in the absence of Lpd without altering their fate or by expressing CXCR4.

To determine whether long-range cues might influence orientation of tangentially migrating Lpd-depleted cells, we scored the direction of their leading processes (Fig. 3f) and observed cells that moved both medial to lateral (from the cortex towards the ganglionic eminence) and lateral to medial (from the cortex towards the midline). Although a slight directional bias was observed, we conclude that tangential migration of these neurons likely occurs independently of specific lateral or medial diffusible long-range signals.

We next asked whether tangential migration of Lpd depleted neurons could potentially arise from decreased preference for glial contact, increased preference for migration on or among axons in the axon-rich SVZ/IZ, or both. The vast majority of tangentially oriented cells had a leading process that appeared to be closely apposed to axon fiber tracts (90% ± 0.17; n = 3 embryos; Fig. S5a). Using an in vitro culture system, we observed an increased propensity of Lpd depleted cortical neurons to adhere to cortical axon bundles compared to control (Fig. S5b), raising the possibility that Lpd inactivation caused pyramidal neurons to select axon fiber tracts for tangential migration instead of their normal substrate, radial glia. However, these observations alone are not sufficient to conclude unequivocally that Lpd knockdown neurons migrate tangentially using axons as their substrate.

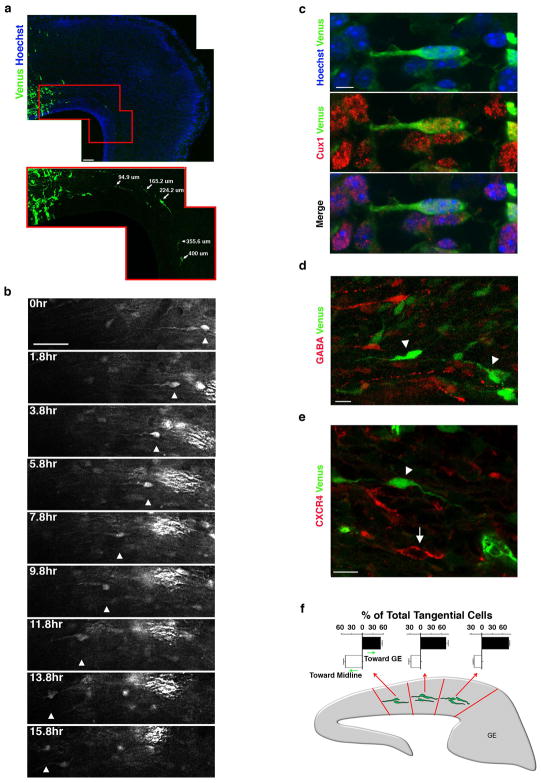

How does Lpd expression ensure radial glia-guided migration rather than tangential migration? Lpd depletion in cultured cells or in Drosophila decreases the ratio of filamentous (F) to monomeric (G) actin 5, 18. We observed that Lpd depletion in cortical neurons resulted in a reduction in F-actin levels (Fig. 4a). One way cells adjust to changes in F:G actin ratios involves altered activity of serum response factor (SRF), which together with its co-activator MAL, regulates expression of many cytoskeleton- and adhesion-related genes; when the F:G-actin ratio falls below a critical threshold, G-actin monomer binds to MAL and inhibits its ability to activate SRF 19, 20. We used an in vivo SRF reporter assay to examine the effects of Lpd knockdown in the cortex and observed a 4-fold reduction in SRF-responsive gene expression compared to control (Fig. 4b). We hypothesized that reduced SRF activity might mediate part or all of the Lpd-knockdown phenotype. Consistent with this idea, shRNA-mediated SRF knockdown resulted in the appearance of tangentially oriented bipolar pyramidal neurons, similar to those observed after Lpd depletion (Fig 4c and Supplemental Information S6a). SRF depletion, however, caused an additional neurogenesis defect. Since effective SRF knockdown required expression of the shRNA in neuronal progenitors, it was impossible to evaluate SRF depletion in neurons without also perturbing neurogenesis. To circumvent this problem, we used two well established methods to inhibit SRF selectively in post-mitotic cells: expression of an SRF dominant negative (DN-SRFΔC) that lacks the C-terminal activation domain, or expression of a non-polymerizable β-actin mutant (R62D) that binds to MAL and inhibits its ability to activate SRF 21, 22. As judged by the in vivo reporter assay, SRF activity was reduced significantly by neuronal-specific expression of DN-SRFΔC or R62D (Fig. 4b). Strikingly, electroporation of either DN-SRFΔC or R62D resulted in tangentially oriented bipolar neurons in the SVZ and lower IZ (Figs. 4d, S6b), a phenotype virtually identical to that of Lpd-depleted neurons. Therefore, similar to Lpd depletion, reduction in SRF activity in post-mitotic neurons results in a shift to tangential orientation.

Figure 4. Lpd affects the orientation of cortical bipolar cells through an SRF/MAL-dependent pathway.

(a–d) Mouse embryos were electroporated in utero at E14.5 and harvested at E18.5. (a) Expression levels of rhodamine-phalloidin (red) in control and Lpd shRNA bipolar cells that co-express Venus in the SVZ/IZ. Nuclei were visualized with Hoechst 33342 dye (blue). Scale Bar: 5 μm. Quantification of F-actin levels in Lpd knock-down tangentially oriented and control bipolar neurons as measured by relative phalloidin fluorescence intensity normalized to background fluorescence intensity (***p<0.001; cells from 3 control and 3 Lpd shRNA brains were included for quantification). (b) In utero luciferase reporter assay. Tissue was from brains that were co-electroporated with SRF reporter 3D. ALuc and pRL-TK plasmids along either Lpd shRNA, control (Ctrl) shRNA, or control (empty NeuroD1 vector), DN-SRF, or R62D expression vectors and subsequently analyzed for luciferase activity. Lpd knockdown significantly decreased SRF activity, represented by the relative firefly luciferase activity normalized to Renilla luciferase activity (*** p <0.001, Student’s t-test, n = 4 brains per condition) (* p <0.05, ** p <0.01, one-way ANOVA, n = 4–6 brains per condition). (c) Percentage of control and SRF knockdown (* p <0.05, Student’s t-test, n = 3 brains per condition) or (d) control, DN-SRF, and R62D bipolar cells that are tangentially oriented (leading process angles between 30° and −30°) in the IZ/SVZ (*** p <0.001, one-way ANOVA, n = 3 brains per condition).

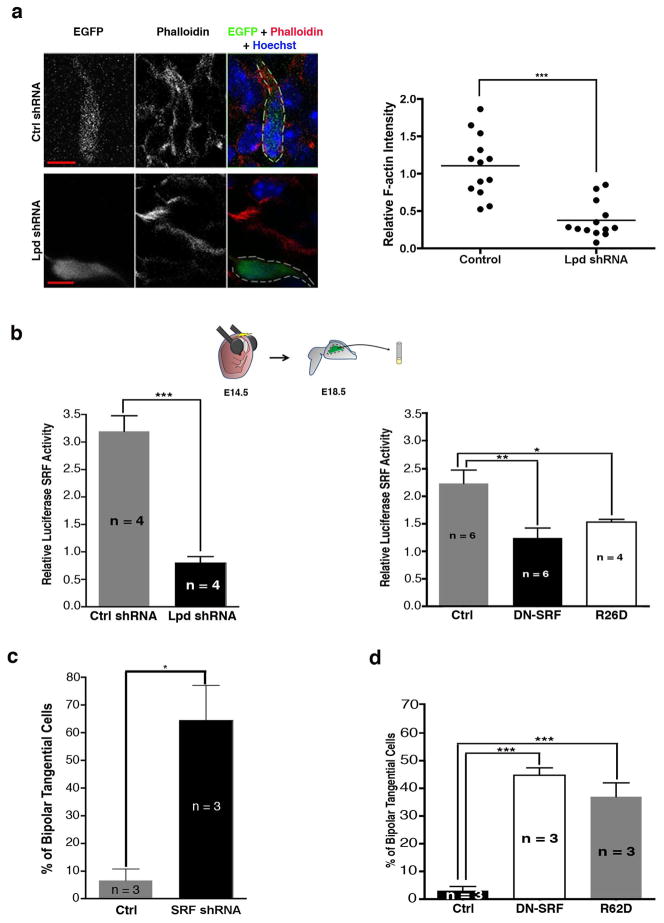

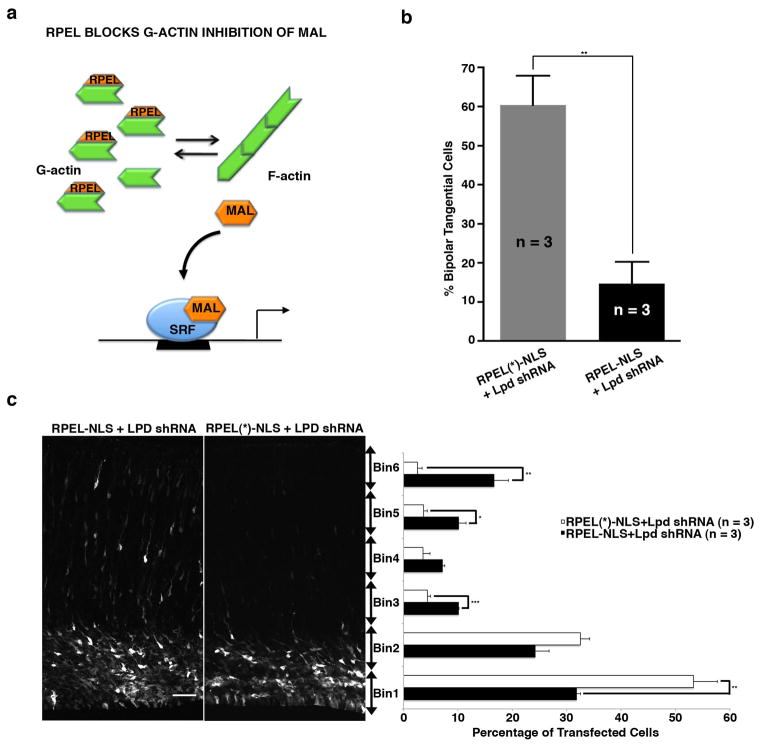

To test whether reduced SRF activity was essential for the Lpd knockdown phenotype, we utilized an established approach to bypass the ability of excess G-actin (present in Lpd-depleted cells) to inhibit SRF activity23. To prevent G-actin from binding to-, and inhibiting the SRF co-activator MAL, we expressed the actin-binding domain within MAL (RPEL) fused to a heterologous nuclear import signal (RPEL-NLS), which acts as a G-actin “sponge”. Expression of RPEL-NLS is known to specifically and effectively restore SRF activity in the presence of low F:G actin levels by preventing excess G-actin from inhibiting MAL-dependent SRF activation23(Fig. 5a). Co-electroporation of RPEL-NLS with the Lpd shRNA rescued both cell positioning (Fig. 5c) and bipolar tangential cell phenotypes (Fig. 5b) typical of Lpd depletion. However, co-electroporation of an actin-binding defective RPEL construct, “RPEL(*)-NLS”, with the Lpd shRNA resulted in a phenotype indistinguishable from Lpd knockdown alone. Therefore, Lpd depletion induces the bipolar tangential migration phenotype as a consequence of increased G-actin levels that inhibit MAL activation of SRF (S6c,d). These three independent approaches to perturb G-actin-dependent regulation of SRF via its co-factor MAL are all consistent with the hypothesis that tangential orientation and migration of Lpd-depleted bipolar neurons arise as a consequence of reduced SRF activity.

Figure 5. Expression of MAL G-actin binding motifs (RPEL) rescues the Lpd knockdown orientation and positioning defects of bipolar pyramidal neurons.

Mouse embryos were electroporated in utero at E14.5 and harvested at E18.5. (a) Schematic representation of SRF/MAL activity upon RPEL-NLS23 rescue of the Lpd knockdown. (b) Percentage of bipolar tangentially oriented cells in the IZ/SVZ of samples co-electroporated with Lpd knockdown vector and RPEL-NLS or RPEL(*)-NLS containing RPEL motif (mutations) ** p <0.01, Student’s t-test, n = 3 brains per condition). Bar graphs are plotted as mean ± SEM. (c) Quantification of cell distribution in cortical sections co-electroporated with Venus, Lpd shRNA and either RPEL-NLS or RPEL(*)-NLS containing mutations in the RPEL motif that disrupts G-actin binding. (* p <0.05, **p <0.01, *** p <0.001, Student’s t-test, n = 3 brains per condition). Scale bars: 50 μm. Bar graphs are plotted as mean ± SEM.

Altogether, these experiments indicate that Lpd depletion perturbs an SRF/MAL-dependent pathway that ensures that pyramidal neurons migrate along radial glia rather than tangentially. Since the Lpd knockdown neuronal migration phenotype was rescued by uncoupling the ability of excess G-actin to block MAL-dependent SRF activation, Lpd depletion has no other obvious effect on cortical neuronal migration independent of G-actin inhibition of MAL-dependent SRF activation. Therefore, Lpd function may not be required directly for radial migration of pyramidal neurons. Instead, the migration phenotypes described here appear to result solely from the inability of neurons to maintain proper F:G-actin ratios in the absence of Lpd, leading to attenuation of SRF activity. Given the ability of R62D G-actin expression to phenocopy Lpd-depletion, it is likely that perturbation of other regulatory molecules that reduce F:G actin ratios and shut down MAL-dependent SRF activation might also induce a similar phenotype. Thus, Lpd inactivation exposed an unexpected SRF/MAL dependent function in cortical development.

This study provides the first evidence that pyramidal neurons have the intrinsic capacity to switch to tangential migration without changing fate or upregulating CXCR4. Although previous studies have identified many molecules important for radial migration of pyramidal neurons, it remains unclear why these neurons migrate radially instead of tangentially. To our knowledge, this is the first example of a regulatory pathway that instructs pyramidal neurons to migrate along radial glia rather than taking a tangential pathway. This change in behavior of pyramidal neurons may be due to a defect in their ability to choose to migrate along glia. Connexins play a role in regulating adhesion of migrating neurons to radial glia fibers 24,25, however, silencing of connexins impairs radial migration without causing tangential migration of pyramidal neurons 25, suggesting that defective neuron:glia adhesion alone is insufficient to cause neurons to switch to a tangential pathway. Alternatively, attenuation of SRF activity may cause pyramidal neurons to respond to a migration cue present in the IZ/SVZ or to exhibit increased adhesion to a non-radial glial substrate in the IZ/SVZ that causes tangential migration parallel to axon fiber tracts, raising the possibility that they migrate along axons. Consistent with this possibility, Lpd-depleted neurons were in close proximity to axons in vivo and exhibited increased adhesion to axons in vitro. Whether Lpd-depletion causes pyramidal neurons to contact axons directly is a question for future work. Furthermore, it would be intriguing to determine if Lpd/SRF function affects different types of migration that follow bundled axons such as tumors that invade by spreading along axon fiber tracts.

The vertebrate cortex is a rapidly evolving structure that depends on the appropriate migration and allocation of pyramidal neurons, 80% of all cortical neurons. The present work has identified a mechanism controlling a fundamentally important aspect of pyramidal neuronal migration. Our finding that SRF-dependent transcription drives pyramidal neurons to migrate radially suggests that changes in the expression of SRF targets are sufficient to change migration from radial-glial dependent to tangential; identification of relevant SRF transcriptional targets will provide valuable insight into how pyramidal neurons choose their migration pathway.

METHODS

Animals

All animal work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at MIT. Swiss Webster pregnant female mice were purchased from Taconic.

Plasmids and RNAi

The pSilencer-based shRNA plasmids were generated as previously described 26. The following target sequences were used for Lpd, 5′-GAGATTGACCATGGTGCTG-3′ and control, 5′-CGGCTGAAACAAGAGTTGG-3′. The full-length Lpd cDNA was amplified by PCR using the IMAGE clone 30011296 (for exons 1–13) and the BAC clone RP24-287F10 (for exon 14) as templates. This full-length cDNA was inserted into the pCAX vector in-frame with EGFP under the chicken β-actin (CAG) promoter. For the expression of an shRNA-resistant silent mutant of Lpd, the shRNA targeting sequence “GAGATTGACCATGGTGCTG” in Lpd was mutated to “GAAATCGATCACGGAGCTG” by site-directed mutagenesis. These mutations do not alter amino acid coding. Full-length EGFP-Lpd and EGFP-Lpd silent mutant were also cloned into the pIRES2 vector containing a NeuroD1 promoter. pCAGIG-Venus was described previously26. The SRF C-terminal deletion mutant (aa1-338) and β-actin R62D (an actin derivative) 20 were cloned into the pIRES2 vector containing a NeuroD1 promoter. MAL RPEL-NLS (amino acids 2–261), containing the SV40 large T antigen NLS (PPKKKRKV) C-terminal to the HA-tags and one linking Gly 23 was cloned into pCAGIG-Venus. A derivative of this construct containing point mutations in the RPEL motif (MAL 123-1A) 23 was used as a negative control. The SRF reporter 3D. ALuc 27, and a Renilla-Luc-TK reporter (pRL-TK, Promega, Madison, WI) were used for testing SRF transcriptional activity.

Antibodies and immunohistochemistry

Rabbit anti-Lpd (1:1000) and mouse anti-α tubulin (1:7000) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) antibodies were used for Western blot analysis. The following antibodies were used for Immunohistochemistry: mouse anti-NF (2H3, 1:200), (DSHB, Iowa City, IA), L1 (1:100) (Millipore, Billerica, MA), GABA (1:1000) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), mouse anti-Nestin (1:1000) (BD Biosciences, Woburn, MA), rabbit anti-Cux1 (1:100) (Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit Cleaved Caspase-3 (1:200) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), rabbit anti-CXCR-4 (1:50) (Genetex, Irvine, CA), mouse anti-Tau-1 (1:500) (Chemicon, Billerica, MA), and chicken anti-GFP (1:500) (Aves Labs, Tigard, OR). Nuclei were visualized with Hoechst 33258. Immunofluorescence samples were processed as previously described 26. Cryosections of 30–50 μm were prepared from E13.5 and E18.5 embryos. For GABA staining, embryos were fixed by transcardial perfusion with PBS followed by 4% PFA in PBS. The forebrains from the perfused embryos were post-fixed for 30 min in 4% PFA and then vibratome sectioned (50 μm). For CXCR-4 staining signal amplification was performed using anti-rabbit IgG-Biotinylated (THERMO Scientific 1:200) and 595-Streptavidin (1:1000).

In utero electroporation

Electroporations were performed on timed pregnant Swiss-Webster mice at embryonic stages E11.5 through E14.5 as previously described 26. Sequential electroporation experiments were performed at E13.5 and subsequently at E14.5 and harvested 4 days later. One microliter of DNA solution (a 5:1 or 10:1 ratio of Lpd shRNA to mCherry/Venus; a 5:5:1 ratio of Lpd shRNA, Lpd rescue construct, and mCherry; or a 3:1 ratio of expression vectors to mCherry) was injected into the lateral ventricle of embryos through the uterine wall, and electrical pulses were applied (five repeats of 24–38 V for 50 ms with an interval of 950 ms) using an Electro Square Porator ECM830 (Genetronics, San Diego, CA). Two to four days after electroporation, embryos were dissected, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), and prepared for cryosectioning.

Brain slice culture and time-lapse imaging

Acute brain slices were prepared from electroporated mouse embryos as described 26. Slices were cultured on Millicell-CM inserts (Millipore, Billerica, MA) in Neurobasal medium supplemented with B27, 0.5 mM glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 5% horse serum for 1hr before time-lapse imaging on a Deltavision Spectris deconvolution system (Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA) using a 20X wide field lens. Images were acquired in the lateral region of the neocortex at 10 min intervals for 14–16 hr.

Luciferase assays

For the in utero SRF reporter assay, expression vector, SRF reporter 3D. ALuc 27, pRL-TK (Promega, Madison, WI), and pCAX-mCherry constructs were electroporated into E14.5 embryonic brains at a 5:1:0.3:1 ratio. SRF activity was measured at E18.5 using the Dual-Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI). All firefly luciferase activities were normalized with Renilla luciferase activity.

Imaging and statistical analysis

Images were obtained using a confocal Zeiss LSM 510 microscope. Statistical analyses were performed using the PRISM software. All bar graphs were plotted as mean ±SEM. Multiple group comparisons were made using one-way (ANOVA) and direct comparisons made using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test.

Quantification of cell distribution

Confocal images were obtained from cryosections at comparable transfected neocortical regions and analyzed using the LSM Image Browser (Zeiss). For the neuronal positioning phenotype, a total of 3 evenly spaced rostral to caudal sections per brain from 4–5 brains per condition were analyzed. The cortex was divided into 6 equal areas and the fraction of cells in each designated bin was quantified and averaged across slices. For bipolar cell distribution experiments, confocal stacks in the SVZ/IZ region were collected from the medial-lateral region of 7–10 slices per brain from 3 brains per condition. The angle of the leading process of each bipolar cell was determined with respect to the ventricular surface. Bipolar cells whose leading processes fell within 30° and −30 were categorized as tangentially oriented cells. These cells were quantified and averaged across slices.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Richard Treisman for providing DNA constructs. E.M.P. was support by a NRSA grant F32-GM074507. This work was supported by funds from NIH grant # GM068678 to F.B.G. L.-H. T. is an investigator of Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

E.M.P. designed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the paper. Z. X. designed and performed experiments. A.L.N. performed experiments. M.V. performed experiments. E.M.P., Z. X., and F.B. discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages. F.B. designed experiments, gave technical support and conceptual advice and revised the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ayala R, Shu T, Tsai LH. Trekking across the brain: the journey of neuronal migration. Cell. 2007;128:29–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marin O, Rubenstein JL. Cell migration in the forebrain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2003;26:441–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rakic P. Developmental and evolutionary adaptations of cortical radial glia. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:541–549. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.6.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han J, et al. Reconstructing and deconstructing agonist-induced activation of integrin alphaIIbbeta3. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1796–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krause M, et al. Lamellipodin, an Ena/VASP ligand, is implicated in the regulation of lamellipodial dynamics. Dev Cell. 2004;7:571–583. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lafuente EM, et al. RIAM, an Ena/VASP and Profilin ligand, interacts with Rap1-GTP and mediates Rap1-induced adhesion. Dev Cell. 2004;7:585–595. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michael M, Vehlow A, Navarro C, Krause M. c-Abl, Lamellipodin, and Ena/VASP proteins cooperate in dorsal ruffling of fibroblasts and axonal morphogenesis. Curr Biol. 2010;20:783–791. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adler CE, Fetter RD, Bargmann CI. UNC-6/Netrin induces neuronal asymmetry and defines the site of axon formation. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:511–518. doi: 10.1038/nn1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang C, et al. MIG-10/lamellipodin and AGE-1/PI3K promote axon guidance and outgrowth in response to slit and netrin. Curr Biol. 2006;16:854–862. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manser J, Wood WB. Mutations affecting embryonic cell migrations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Genet. 1990;11:49–64. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020110107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quinn CC, et al. UNC-6/netrin and SLT-1/slit guidance cues orient axon outgrowth mediated by MIG-10/RIAM/lamellipodin. Curr Biol. 2006;16:845–853. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fode C, et al. A role for neural determination genes in specifying the dorsoventral identity of telencephalic neurons. Genes Dev. 2000;14:67–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hand R, et al. Phosphorylation of Neurogenin2 specifies the migration properties and the dendritic morphology of pyramidal neurons in the neocortex. Neuron. 2005;48:45–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kriegstein AR, Noctor SC. Patterns of neuronal migration in the embryonic cortex. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yokota Y, et al. Radial glial dependent and independent dynamics of interneuronal migration in the developing cerebral cortex. PLoS One. 2007;2:e794. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez-Alcaniz JA, et al. Cxcr7 controls neuronal migration by regulating chemokine responsiveness. Neuron. 69:77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, et al. CXCR4 and CXCR7 have distinct functions in regulating interneuron migration. Neuron. 69:61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyulcheva E, et al. Drosophila pico and its mammalian ortholog lamellipodin activate serum response factor and promote cell proliferation. Dev Cell. 2008;15:680–690. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miralles F, Posern G, Zaromytidou AI, Treisman R. Actin dynamics control SRF activity by regulation of its coactivator MAL. Cell. 2003;113:329–342. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Posern G, Treisman R. Actin’ together: serum response factor, its cofactors and the link to signal transduction. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:588–596. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansen FE, Prywes R. Identification of transcriptional activation and inhibitory domains in serum response factor (SRF) by using GAL4-SRF constructs. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4640–4647. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Posern G, Sotiropoulos A, Treisman R. Mutant actins demonstrate a role for unpolymerized actin in control of transcription by serum response factor. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4167–4178. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-05-0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vartiainen MK, Guettler S, Larijani B, Treisman R. Nuclear actin regulates dynamic subcellular localization and activity of the SRF cofactor MAL. Science. 2007;316:1749–1752. doi: 10.1126/science.1141084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elias LA, Turmaine M, Parnavelas JG, Kriegstein AR. Connexin 43 mediates the tangential to radial migratory switch in ventrally derived cortical interneurons. J Neurosci. 30:7072–7077. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5728-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elias LA, Wang DD, Kriegstein AR. Gapjunction adhesion is necessary for radial migration in the neocortex. Nature. 2007;448:901–907. doi: 10.1038/nature06063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie Z, et al. Cep120 and TACCs control interkinetic nuclear migration and the neural progenitor pool. Neuron. 2007;56:79–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geneste O, Copeland JW, Treisman R. LIM kinase and Diaphanous cooperate to regulate serum response factor and actin dynamics. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:831–838. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.