Abstract

Planar cell polarity (PCP) is the collective polarization of cells along the epithelial plane, a process best understood in the terminally differentiated Drosophila wing. Proliferative tissues such as mammalian skin also display PCP, but the mechanisms that preserve tissue polarity during proliferation are not understood. During mitosis, asymmetrically-distributed PCP components risk mislocalisation or unequal inheritance, which could have profound consequences on the long-range propagation of polarity. Here, we show that when mouse epidermal basal progenitors divide, PCP components are selectively internalized into endosomes, which are inherited equally by daughter cells. Following mitosis, PCP proteins are recycled to the cell surface where asymmetry is re-established by a process reliant upon neighbouring PCP. A cytoplasmic dileucine motif governs mitotic internalization of atypical cadherin Celsr1, which recruits Vang2 and Fzd6 to endosomes. Moreover, embryos transgenic for a Celsr1 that cannot mitotically internalize, exhibit perturbed hair follicle angling, a hallmark of defective PCP. This underscores the physiological relevance and importance of this novel mechanism for regulating polarity during cell division.

Despite constant turnover, mammalian skin maintains a uniform pattern of anterior-oriented hair follicles across the body surface. The process is controlled by the PCP pathway, which orients cell polarity across remarkably diverse tissues1–3. First discovered in Drosophila, two mechanisms of PCP are particularly conserved: asymmetric redistribution of core components Frizzled/Fzd, VanGogh/Vangl, Flamingo/Celsr, Dishevelled/Dvl and Prickle4–12, and non-autonomous propagation of polarity cues mediated by transmembrane components Frizzled, VanGogh and Flamingo13–16. How planar asymmetry and the cell-to-cell transmission of polarity cues are regulated in the proliferative cells of highly regenerative tissues is currently unknown.

In skin, PCP components are expressed and asymmetrically localized in basal epidermal stem cells (basal cells), proliferative progenitors that give rise to hair follicles and replenish the skin’s outer stratified layers throughout life. Beginning at embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5), basal cells asymmetrically localize Celsr1, Vangl2 and Fzd6 along anterior-posterior sides of the plasma membrane2. The proper orientation of subsequently developing hair follicles depends upon planar polarity in basal cells, and disruption of PCP in genetically mosaic animals alters orientation of neighbouring wild-type hair follicles nonautonomously1,2,17. The long-range consequences of local disruptions to PCP raise a dilemma. How do basal stem cells, which proliferate throughout life, minimize polarity perturbations as they enter mitosis, change shape and rearrange? Are PCP components maintained asymmetrically at the cell surface, and how is their equal distribution between daughter cells ensured?

Here we show that basal epidermal progenitors selectively internalize PCP components during cell division, where they are equally inherited by daughter cells and redelivered to the cell cortex following cytokinesis. We propose that mitotic internalization of PCP proteins provides a means for regenerative tissues to maintain long-range PCP by preventing cells from sending and/or receiving aberrant polarity signals when they are rounded up during the division process. Furthermore, by relying upon the PCP of neighbouring interphase cells, progeny are able to properly relocalise PCP components and reorient themselves following mitosis. This mechanism explains how non-autonomous polarity disruptions are prevented in tissues that must maintain function during growth and/or turnover.

Results

Distribution of PCP components during interphase and mitosis

We previously showed that in interphase, PCP components are asymmetrically enriched along anterior-posterior basal cell borders2. To determine whether the distribution of key PCP components was anterior, posterior or both, we generated transgenic mice expressing Celsr1-GFP or GFP-Vangl2 mosaically, and examined boundaries between GFP+ and GFP− cells. Celsr1-GFP protein accumulated on both anterior and posterior membrane sides (Fig. 1a), consistent with this atypical cadherin’s ability to interact homotypically2,6. By contrast, GFP-Vangl2 preferentially accumulated on the anterior membrane (Fig. 1b; Fig. S1). These localization patterns of Celsr1 and Vangl2 correspond to the asymmetric distribution of their Drosophila counterparts Fmi and Vang in developing wing5,18. Importantly, they reveal that anterior and posterior sides of the epidermal plasma membrane are distinct.

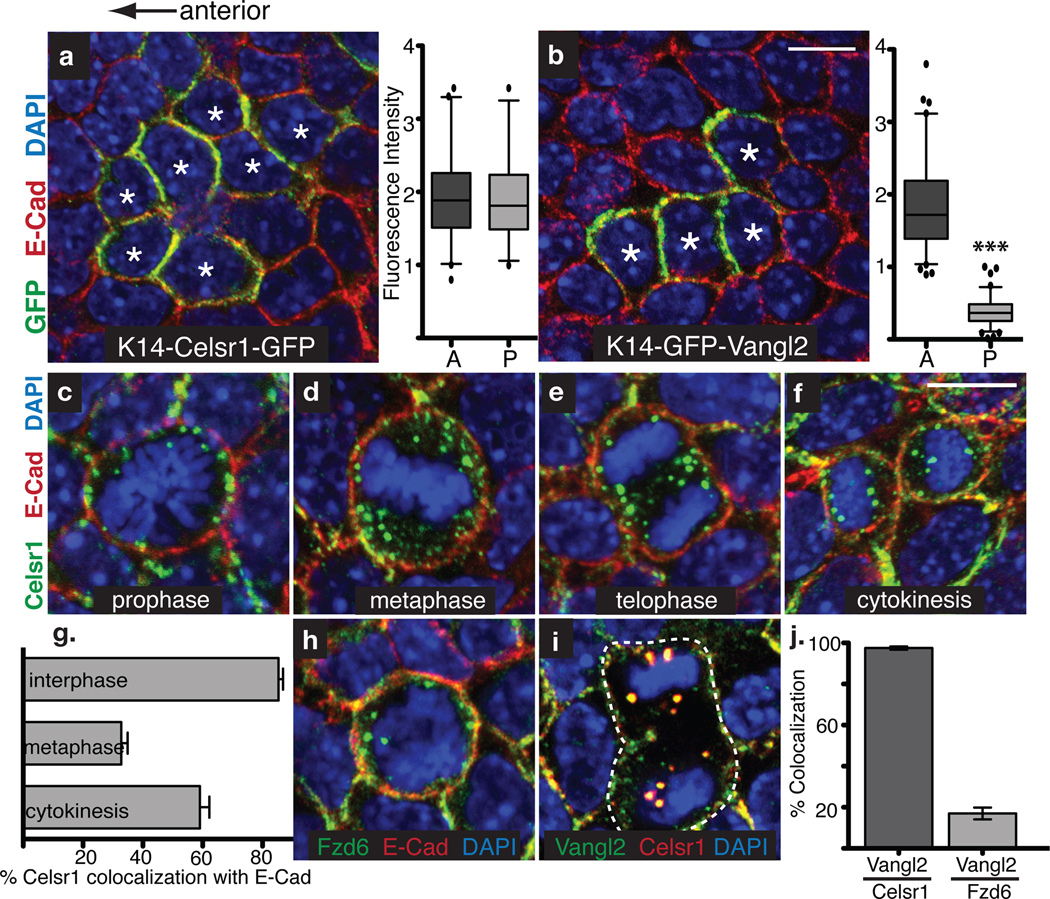

Fig. 1. PCP components are selectively internalized in basal epidermal cells undergoing mitosis.

Images show planar confocal sections through the basal layer of E15.5 mouse backskins. Anterior is to the left. (a) Transgenic embryos mosaically expressing K14-Celsr1-GFP (green). Cell contacts are labelled with E-Cad antibodies (red), and chromatin is labelled with DAPI (blue). Stars mark Celsr1-GFP expressing cells where Celsr1 accumulates on both the anterior and posterior sides of the plasma membrane. Quantification of fluorescence intensity on anterior and posterior clone borders is to the right (n= 65 cells in 26 clones, t-test p=0.8029). (b–b’) Transgenic embryos mosaically expressing K14-GFP-Vangl2 (green). Backskins are stained with E-Cad antibodies (red), and DAPI (blue). Stars indicate cells expressing Vangl2-GFP, which in contrast to Celsr1, accumulates preferentially on the anterior side of the membrane. Quantification of fluorescence intensity on A-P clone borders is to the right (n=93 cells in 22 clones, Mann-Whitney test p<0.0001). (c–f) Examples of Celsr1 distribution in mitotic basal cells at prophase (c), metaphase (d), telophase (e) and cytokinesis (f). E15.5 whole mount backskins were stained with Celsr1 (green) and E-Cad (red) antibodies. DAPI highlights condensed chromosomes of mitotic cells (blue). Note E-Cadherin retains its plasma membrane localization during mitosis. (g) Quantifications of the data in c–f. Shown is he mean percentage of Celsr1 co-localized with E-Cad at the plasma membrane per cell. n=20 cells/ cell cycle stage. (h–i) Fzd6 and Vangl2 (green) internalize and co-localize with Celsr1 (red, i) puncta but not E-Cad (red, h) in mitotic basal cells. (j) Quantification of co-localization between Vangl2 and Celsr1 or Fzd6 puncta. While 97.5+/− 0.8% of Vangl2 puncta contain Celsr1 (n=25 cells), only 17%+/− 2.9% contain Fzd6 (n=10 cells) Error bars denote s.e.m. Scale bars=10µm.

We next examined PCP protein localization in basal cells undergoing mitosis. Unexpectedly and in striking contrast to E-cadherin, endogenous Celsr1 lost plasma membrane localization and gained underlying punctate localization as basal cells entered prophase (Fig. 1c). By metaphase, Celsr1 puncta were mostly intracellular (Fig. 1d) and by anaphase/telophase, they were dispersed throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 1e). Towards the end of cytokinesis, Celsr1 reappeared at the plasma membrane (Fig. 1f and quantifications in 1g).

Interestingly, Fzd6 and Vangl2 also accumulated intracellularly during mitosis. While both proteins co-localized with Celsr1 (Fig. 1h–j, and data not shown), only a fraction of Vangl2 puncta overlapped with Fzd6 (17% ± 3%) (Fig. 1j). Moreover, dividing cells contained more than twice as many Celsr1-positive puncta compared to puncta containing either Vangl2 or Fzd6 (Fig. 2c). These results are not only consistent with Celsr1’s ability to co-localize with both proteins, but also suggest that Vangl2 and Fzd6 occupy distinct membrane domains.

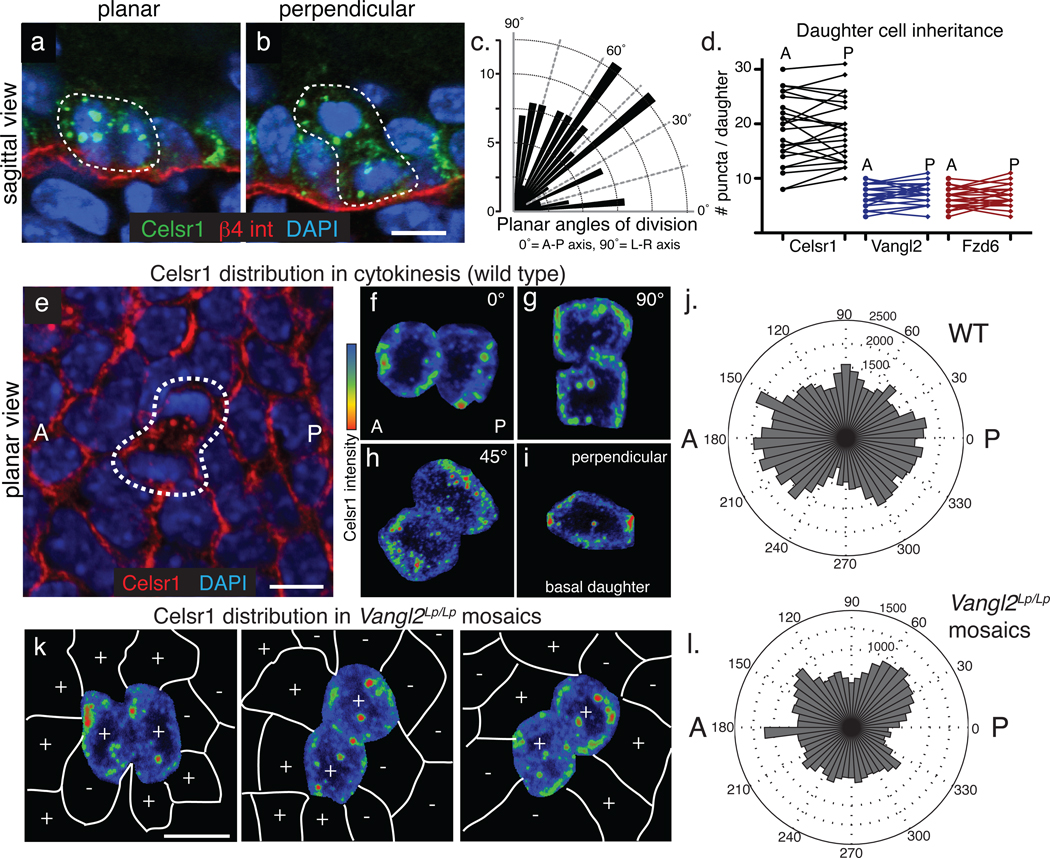

Fig. 2. Mitotically internalized PCP components and inherited equally by both daughter cells and redelivered to the plasma membrane in a polarized manner.

(a–b) Celsr1 internalizes in cells dividing both planar (a) and perpendicular (b) to the basement membrane. Sagittal sections from E17.5 backskins labelled with Celsr1 (green) and β4 integrin (red) to mark the basement membrane. (c) Quantification of division angles within the plane of the basal epithelium. The orientation of division is not strongly biased toward the A-P or L-R axis (n=114 planar divisions). (d) Quantification of puncta per anterior or posterior daughter during cytokinesis. Lines connect daughters from the same division. While the total number of puncta varies with the progression of cytokinesis, similar numbers of puncta are observed in daughter cells. For Celsr1, the average difference (d)=2.6+/− 0.3 puncta between daughters; Vangl2 d=1.2+/− 0.2; Fzd6 d=1.5+/− 0.2 (n=25 daughter pairs). (e–j) Polarized retargeting of Celsr1 to the membrane during cytokinesis. Images show planar confocal projections through dividing cells within the basal layer of E15.5 backskins stained with Celsr1 antibodies. Anterior is to the right. (f–i) Examples of basal cells in cytokinesis extracted from the surrounding epithelia and categorized by orientation of division: ~ 0°, 90°, 45°, and perpendicular to the basal lamina (0°=A-P axis, 90°=L-R axis). Heat maps show Celsr1 intensity (red=high, blue=low). Irrespective of the plane or axis of division, Celsr1 preferentially accumulates on the A-P sides of daughter cells. (j) Quantification of Celsr1 intensity during cytokinesis. Polar plots show the intensity of cortically associated Celsr1 in daughter cells during cytokinesis (n=30 cells; see Methods for details). (k) Celsr1 fluorescence intensity (red=high, blue=low) in Vangl2Lp/Lp embryos mosaically expressing K14-GFP-Vangl2. Vangl2-positive cells are marked with (+) symbols, while Vangl2Lp/Lp cells are marked with (−) signs. Examples of cells dividing in ~0, 90, and 45 orientations are shown. (l) Quantification of Celsr1 intensity during cytokinesis in Vangl2Lp/Lp mosaic embryos (n=18). Note that Celsr1 enrichment along the A-P axis during cytokinesis is lost when neighbouring cells are mutant for Vangl2. Bars=10µm.

Examination of the distribution of other transmembrane proteins associated with cell junctions revealed that PCP components are internalized selectively, if not uniquely, during mitosis. E-Cadherin, P-Cadherin, Nectin, Occludin, and β4 integrin all maintained membrane localization throughout the basal cell cycle (Fig. 1c–h, 2a–b, S2a–d). These data are consistent with ultrastructural analyses showing that epithelia retain intercellular junctions when they divide19,20. Thus, mitotic internalization is not a general property of transmembrane proteins expressed in keratinocytes. Junctional proteins that polarize along the apical-basal axis maintain their membrane localization during mitosis, while PCP proteins uniquely internalize.

Internalized PCP components are inherited equally by daughter cells

We next examined how internalized PCP components are inherited by daughter cells relative to the axis of division. Embryonic basal epidermal cells divide in two main orientations: divisions parallel to the basement membrane (planar) expand the progenitor pool while perpendicular divisions (apico-basal) contribute to stratified outer skin layers21Lechler, 2005 #18. PCP puncta localized to both daughter cells in mitoses oriented along both planar and apico-basal axes (Figure 2a–b). To determine how basal cells divide within the epithelial plane, we quantified the axial orientation of cells in cytokinesis. Planar basal cells divisions were not strongly biased toward the A-P or L-R body axes (Fig. 2c), and irrespective of planar spindle orientation, Celsr1, Vangl2, and Fzd6 partitioned to both daughters in roughly equal numbers (Fig. 2d). These findings indicate that following mitotic internalization, PCP proteins disperse throughout the cytoplasm and become equally inherited by the two daughters.

Polarized membrane accumulation of Celsr1 during cytokinesis

Following cytokinesis, all three PCP components re-establish anterior-posterior localization. To investigate how asymmetry is regained following mitosis, we quantified Celsr1 distribution in cells undergoing cytokinesis. Confocal fluorescence intensity measurements averaged over 30 mitotic cells within the E15.5 basal epidermal plane revealed that Celsr1 accumulated most strongly on the anterior and posterior sides of daughter cells, suggesting it may directionally targeted to the plasma membrane (Fig. 2e–j). Notably, this polarized accumulation appeared to be independent of spindle orientation, since Celsr1 localized asymmetrically along the A-P axis irrespective of the division plane (representative examples shown in Fig. 2f–i; quantifications in 2j).

Given this asymmetric localization bias, we wondered whether the polarity of neighbouring cells might influence directional Celsr1 accumulation. To test this hypothesis, we transgenically rescued Vangl2Lp/Lp embryos with mosaically expressed K14-GFP-Vangl2 to generate animals containing a mix of wild-type and Vangl2Lp/Lp epidermal cells. When wild-type (+) mitotic cells neighboured Vangl2Lp/Lp interphase cells (−), the anterior-posterior enrichment of Celsr1 during cytokinesis was lost (examples in Fig. 2k; quantifications in 2l). These data reveal that polarity is regained during cytokinesis perhaps through directed targeting of PCP-containing puncta to anterior-posterior membrane domains. Furthermore, these results suggest that dividing cells accomplish this by using their interphase neighbours as templates for polarity.

Epidermal PCP components are endocytosed and recycled specifically during mitosis

To explore the mechanism underlying mitotic internalization, we first performed live cell imaging on cultured primary keratinocytes expressing Celsr1-GFP. At the onset of mitosis, cytoplasmic Celsr1-GFP puncta began to appear concomitant with disappearance of junctional Celsr1-GFP. Following cell division, Celsr1-GFP reappeared at sites of intercellular contact (Figs. 3a–b; Supplemental Movie 1). These results demonstrate that mitotic internalization is an inherent property of Celsr1 in epidermal cells that can be recapitulated in vitro.

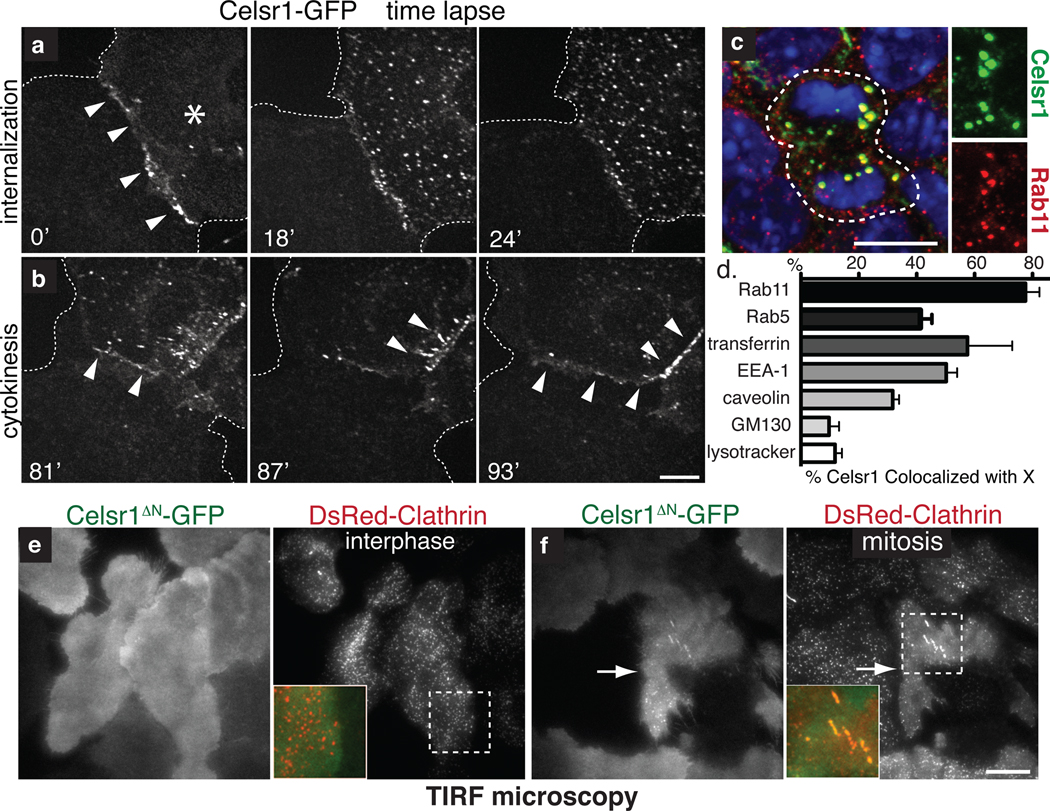

Fig. 3. Upon mitosis, PCP components are endocytosed by a clathrin-dependent mechanism and recycled to the plasma membrane.

(a) Time-lapse images of Celsr1-GFP internalization in a live mitotic keratinocyte in vitro. Cell on the right (asterisk) is undergoing mitosis. Note that Celsr1 localizes to the cell-cell contact during interphase, but internalizes as cell enter mitosis. (b) Time-lapse images of Celsr1-GFP redelivery to sites of intercellular contacts towards the end of mitosis (see Supplementary Movie 1). (c) Celsr1 co-localizes with Rab11, a marker of recycling endosomes, in mitotic basal cells in vivo. Planar confocal sections through the basal layer of E15.5 backskin labelled with Celsr1 (red) and Rab11 (green) antibodies. Right panels show individual channels. Chromatin is labelled with DAPI (blue). (d) Celsr1-GFP co-localizes appreciably with Rab11, early endosome markers Rab5 and EEA-1, and internalized transferrin, a marker of clathrin-dependent endocytosis. Some overlap is observed with caveolae marker caveolin. By contrast, Celsr1-GFP is largely independent of golgi marker GM130, and lysosomal marker lysotracker in mitotic keratinocytes in vitro. Shown is the mean percentage of Celsr1 co-localized with X per cell. n=4–10 cells for each marker. Error bars denote s.e.m. (see Fig. S2 for images). (e–f) Celsr1 internalization is increased during mitosis. TIRF microscopy was performed on live keratinocytes expressing Celsr1ΔN-GFP and DsRed-Clathrin. During interphase Celsr1ΔN-GFP is stably associated at the surface (e). In mitosis, Celsr1ΔN-GFP forms surface puncta which co-localize with DsRed-Clathrin (see quantifications in Fig. 4l and Supplementary Movies 3–4). Bars=10µm.

PCP proteins appeared to be internalized by endocytosis, as Celsr1-containing puncta in mitotic cells co-localized with Rab11, a marker of recycling endocytic vesicles22 (Fig. 3c–d). Moreover, mitotic Celsr1-GFP co-localized with early endosome marker EEA-1 and also internalized transferrin, whose receptor is recycled via clathrin-dependent endocytosis (Fig 3d, S2f–g). Celsr1-GFP also co-localized with Rab5 in some mitotic cells, possibly reflecting transient association with this compartment (Fig. 3d, S2e). A fraction of Celsr1-GFP overlapped with the caveolae marker caveolin (~30%) (Fig. 3d, S2h). By contrast, major overlap was not observed between Celsr1-GFP and golgi marker GM130, or lysosomes (Fig. 3d, S2i–j).

The accumulation of PCP-containing endosomes could either result from a mitosis-specific increase in their internalization or a decrease in their recycling back to the surface23. To directly compare Celsr1 surface dynamics between interphase and mitotic cells, we used TIRF microscopy to image endocytic events occurring at the cell surface of keratinocytes expressing Celsr1ΔN-GFP and DsRed-Clathrin (Fig. 3b, e–f). While DsRed-Clathrin puncta continually appeared and disappeared at the surface of interphase cells, Celsr1ΔN-GFP remained stable and diffusely localized at the membrane (Fig. 3e; Supplementary Movie 2). Upon mitosis, surface Celsr1ΔN-GFP coalesced into dozens of puncta that co-localized with DsRed-Clathrin (Fig. 3f; Supplementary Movie 3). While decreased recycling may also contribute to PCP vesicular accumulation, these results demonstrate that mitosis triggers a dramatic upregulation in PCP endocytosis.

Celsr1 recruits Vangl2 and Fzd6 into mitotic endosomes

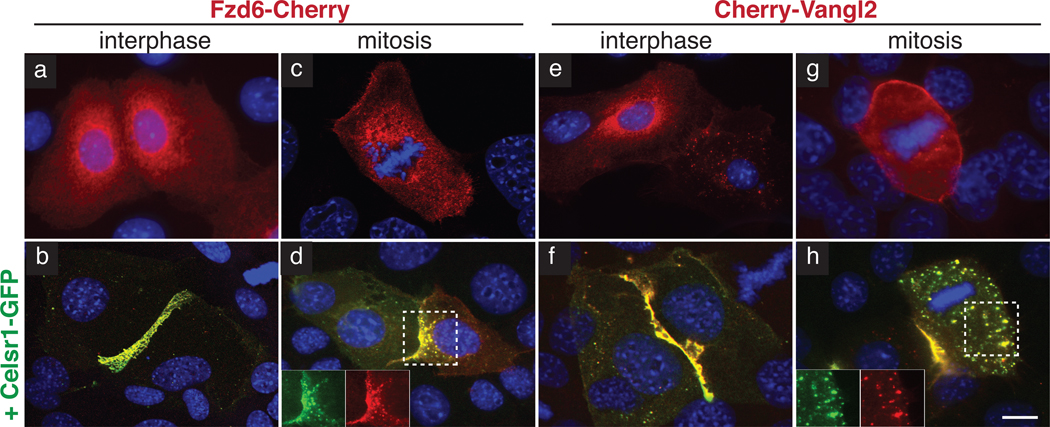

Celsr1, like Fmi in the Drosophila wing, is required to junctionally localize Vangl2 and Fzd6 in keratinocytes2,4,5. Hence, we reasoned that Celsr1 might also recruit Vangl2 and Fzd6 to endosomes during mitosis. Indeed in cultured keratinocytes, which express negligible endogenous Celsr1, Cherry-Vangl2 and Fzd6-Cherry did not localize to cell contacts during interphase, nor did they concentrate into puncta during mitosis (Fig. 4a,c,e,g). Upon Celsr1-GFP co-expression, both Cherry-Vangl2 and Fzd6-Cherry redistributed to mitotic puncta and to cell-cell contacts at interphase (Fig. 4b,d,f,h)2. Based upon these findings, we conclude that Celsr1 functions upstream to localize other PCP components during both interphase and mitosis. We therefore focused on Celsr1 to elucidate how PCP components are internalized.

Fig. 4. Recruitment of Fzd6 and Vangl2 by Celsr1 to cell contacts during interphase and endocytic vesicles during mitosis.

Keratinocytes were transfected with fluorescently-tagged constructs as indicated and shifted to high calcium medium to induce the formation of adherens junctions. Insets show fluorescence channels separately. DAPI staining marks nuclei. (a–b) Fzd6 in interphase. Fzd6-Cherry (red) is recruited to cell contacts only where Celsr1 (GFP-green) homotypically interacts (b). (c–d) Fzd6 in mitosis. Fzd6-Cherry (red) is recruited to endosomes upon co-expression of Celsr1WT-GFP (green, d). (e–f) Vangl2 in interphase. Cherry-Vangl2 (red) is recruited to cell contacts where Celsr1WT-GFP (green, f) homotypically interacts. (g–h) Vangl2 in mitosis. Cherry-Vangl2 (red) is recruited to endosomes by Celsr1WT-GFP (green, h). Bar=10µm.

Celsr1 internalization is mediated by a juxtamembrane dileucine motif

Sorting transmembrane proteins to endosomes typically occurs via recognition of short endocytic motifs within cytoplasmic domains of cargo proteins24. Celsr1’s putative sorting signals could reside within either its cytoplasmic tail or loops between its seven transmembrane passes6. Consistently, deletion of the large N-terminal extracellular domain, including the cadherin repeats necessary for homotypic interactions, had no effect on Celsr1’s internalization (Fig. 5a,b).

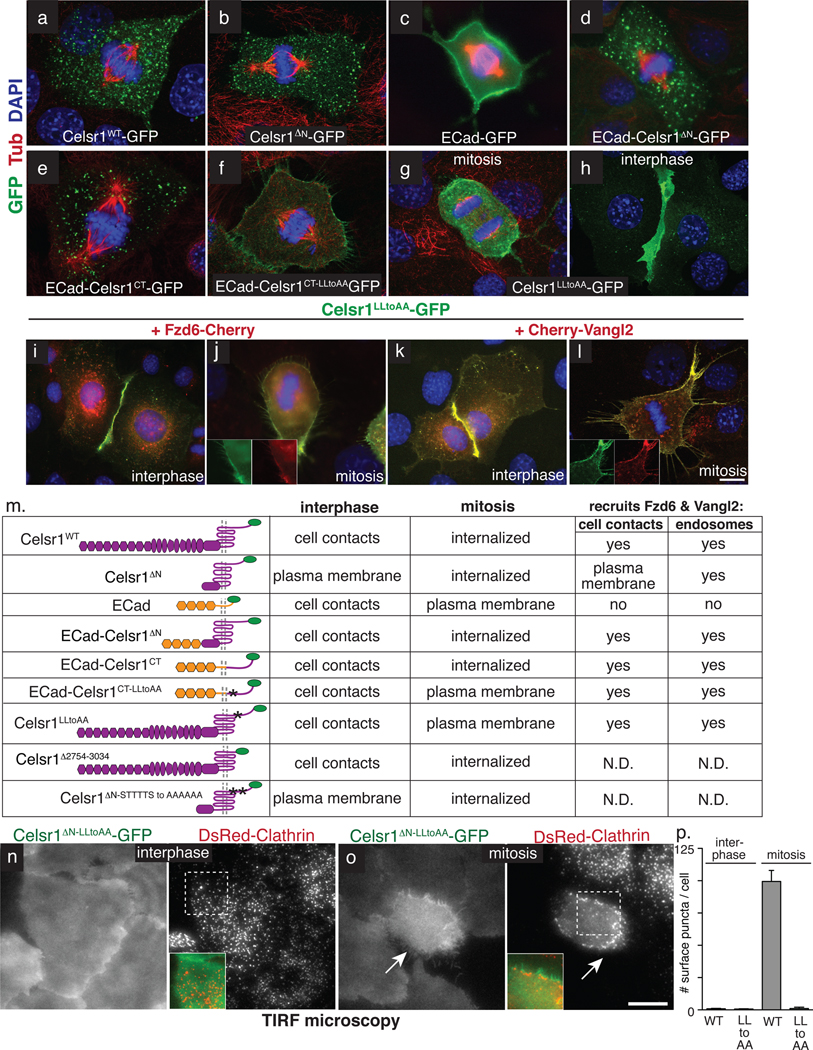

Fig. 5. Mitotic endocytosis of Celsr1 is mediated by a juxtamembrane dileucine motif.

Keratinocytes were transfected with fluorescently-tagged constructs as indicated, which are shown in schematic form in Table m. Celsr1 contains extracellular cadherin repeats (hexagons), laminin repeats (ovals), EGF repeats and a HormD domain, followed by a seven-pass transmembrane domain and 318 amino acid cytoplasmic tail. (a–h) Representative examples of mitotic keratinocytes in vitro labelled with acetylated-tubulin (spindle, red) and DAPI (nuclei, blue), and transfected with expression vectors encoding: (a) Full length wild-type Celsr1-GFP. (b) Celsr1ΔN-GFP lacking its cadherin, laminin, and EGF repeats. (c) Full length wild-type E-Cadherin-GFP. (d) Fusion protein between E-Cadherin extracellular domain and Celsr1’s transmembrane and C-terminal tail domains. (e) Fusion between E-Cadherin’s extracellular and transmembrane domains and Celsr1’s cytoplasmic tail. (f) Mutation of two juxtamembrane leucines to alanines in the cytoplasmic domain of Celsr1, fused to the extracellular and transmembrane domains of E-cadherin. (g–h) Full length Celsr1LLtoAA-GFP in interphase and mitosis. Note the LLtoAA mutation (amino acids 2748–2749) does not affect the localization to cell-cell contacts (h). (i) Fzd6 in interphase. Fzd6-Cherry (red) is recruited to cell contacts only where Celsr1 (GFP-green) homotypically interacts and the LLtoAA mutation does not impair this function. (j) Fzd6 in mitosis. Fzd6-Cherry (red) localizes to the cell cortex in Celsr1LLtoAA-GFP (green) expressing cells undergoing mitosis (compare to Figure 3). Insets show fluorescence channels separately. (f) Vangl2 in interphase. Cherry-Vangl2 (red) is recruited to cell contacts where Celsr1LLtoAA-GFP (green) homotypically interacts. (l) Vangl2 in mitosis. Cherry-Vangl2 (red) is recruited to the cell cortex in Celsr1LLtoAA-GFP (green) expressing mitotic keratinocytes. (m) Table summarizing results presented in Fig. 5a–l and Fig. S3–4. (n–o) TIRF microscopy was performed on living keratinocytes expressing Celsr1ΔNLLtoAA-GFP and DsRed-Clathrin. During interphase Celsr1ΔNLLtoAA-GFP is indistinguishable from WT (compare to Fig. 3e). In mitosis Celsr1ΔNLLtoAA-GFP fails to form puncta and does not co-localize with DsRed-Clathrin (see Supplementary Movies 5–6). (p) Quantification of Celsr1ΔN-GFP and Celsr1ΔNLLtoAA-GFP surface puncta per cell by TIRF in interphase (n=20 cells per construct) and mitosis (n=7 cells per construct). Error bars denote s.e.m. Bars=10µm.

We next tested whether Celsr1 sequences could drive mitotic internalization of E-Cadherin. On its own, E-Cadherin-GFP remained at the membrane during mitosis (Fig. 5c). However, a hybrid swapping E-cadherin’s transmembrane and cytosolic domains for those of Celsr1, was internalized during mitosis, as was an E-Cadherin hybrid containing just Celsr1’s cytoplasmic tail (Figs. 5d–e). Importantly, these fusion proteins localized to cell-cell contacts during interphase, indicating that their internalization is mitosis-specific (Fig. S3a–f). Furthermore during mitosis, GFP-tagged ECad-Celsr1 chimeras recruited Vangl2 and Fzd6 and internalized with full-length Celsr1-Myc, thus co-localizing and trafficking to the same endocytic compartment (Fig. S3g–h, j–k, and data not shown). This narrowed the mitotic internalization motif to Celsr1’s 318 residue cytoplasmic tail.

Classical endocytic recognition sequences commonly contain tyrosine (NPXY or YXXϕ) or dileucines ([DE]XXXL[LI] or DXXLL)24. While Celsr1 does not contain either motif in a canonical form, it does harbour two sequential leucines near its transmembrane domain. Moreover, upon their mutation to alanine, chimeric GFP-tagged Ecad-Celsr1 remained at the membrane and failed to internalize during mitosis (Fig. 5f, compare with WT in Fig. S3i). This dileucine motif appeared to be the primary endogenous sorting signal required for mitotic endocytosis, since its mutation in full-length Celsr1 perturbed the endocytic internalization of this core PCP component during mitosis (Fig. 5g). Celsr1LLtoAA-GFP also retained Cherry-Vangl2 and Fzd6-Cherry at the mitotic plasma membrane, further supporting the notion that Celsr1 acts upstream in mitotic internalization (Fig. 5j,l). Importantly the LLtoAA mutation did not affect interphase functions of Celsr1 including homotypic adhesion and recruitment of Cherry-Vangl2 and Fzd6-Cherry to cell-cell contacts (Fig. 5h,i,k).

To rule out the possibility that mutation of the dileucine motif caused a general defect in Celsr1 membrane surface dynamics, we imaged Celsr1ΔNLLtoAA-GFP by TIRF microscopy. During interphase, Celsr1ΔNLLtoAA-GFP behaved similarly to wild-type, exhibiting comparable surface dynamics. Throughout mitosis, however, Celsr1ΔNLLtoAA-GFP remained aberrantly at the cell surface while its wild-type counterpart was internalized (Fig. 5n–p; Supplemental Movies 4–5). These results show that mutation of the dileucine motif selectively disrupts the mitosis-specific endocytosis of Celsr1.

Many events driving mitosis are governed by phosphorylation, leading us to wonder whether cell cycle dependent phosphorylation might also control mitosis-specific recognition of Celsr1’s endocytic motif. We first showed that deletion of Celsr1’s carboxy terminal 280 amino acids had no effect on its mitotic endocytosis, thereby restricting its cell cycle-dependent regulatory motifs to the 38 juxtamembrane amino acids (Fig. S4a–b). We next focused on a predicted Aurora kinase phosphorylation site directly adjacent to Celrs1’s dileucine motif. However, mutating this site as well as the five serines and threonines surrounding it still failed to abrogate Celsr1 internalization (Fig. S4a, c). Taken together, these findings show that if post-translational modifications regulate the mitotic specificity of Celsr1 endocytosis, mechanisms other than phosphorylation must be involved.

Summarized in Fig. 5m, these collective data show that Celsr1’s C-terminal cytoplasmic tail is sufficient to direct transmembrane protein internalization in a mitosis-specific manner and recruit Vangl2 and Fzd6 to endosomes during cell division. Furthermore, within Celsr1’s cytoplasmic tail, it is the juxtamembrane dileucine motif that is necessary for its mitotic endocytosis.

Mutation of Celsr1’s mitotic internalization motif disrupts epidermal planar polarity in vivo

To determine whether mitotic internalization is a physiologically important step in the epidermal PCP pathway, we generated transgenic mouse embryos that mosaically express Celsr1LLtoAA-GFP or Celsr1WT-GFP in skin at levels comparable to or less than those of endogenous Celsr1 (Figure S5f). As expected, our Celsr1WT-GFP control paralleled endogenous Celsr1, localizing asymmetrically along the A-P axis in basal cells through interphase, and internalizing in endocytic vesicles during mitosis (Fig. 6a,b). By contrast, Celsr1LLtoAA-GFP remained at the plasma membrane during mitosis, but was localized asymmetrically in basal cells during interphase (Fig. 6c–d). However, in contrast to Celsr1WT-GFP transgenics, polarity in Celsr1LLtoAA-GFP basal cells was not strictly oriented along the A-P axis (see below).

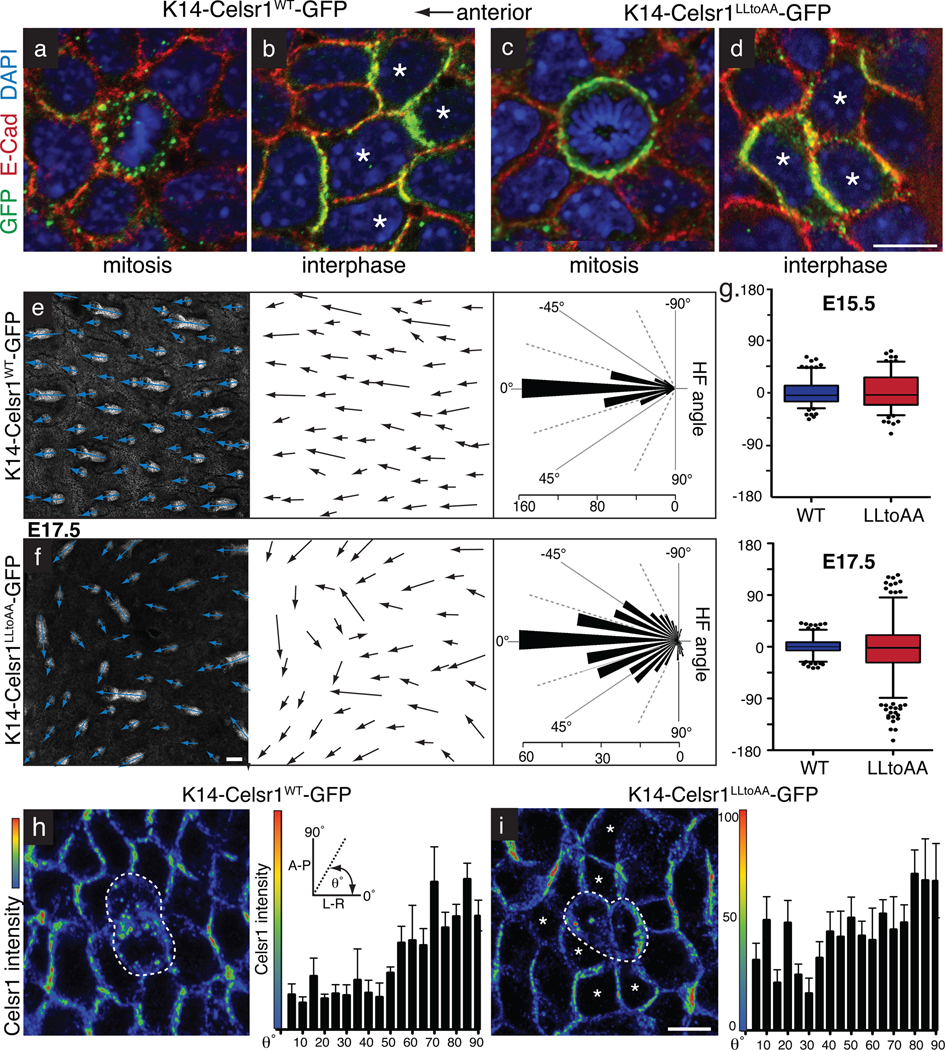

Fig. 6. Mitotic endocytosis of PCP components in basal stem cells is essential for PCP-mediated hair follicle orientation in the skin.

Transgenic founder embryos mosaically expressing WT or LLtoAA-mutant Celsr1-GFP (green) in the skin epidermis. Planar confocal sections through the basal layer of E17.5 whole mount backskins stained with GFP and E-Cad antibodies and DAPI. Anterior is to the left. (a) WT Celsr1-GFP displaying internalization in a mitotic basal cell. (b) WT Celsr1-GFP during interphase is asymmetric localized to the anterior-posterior sides of the plasma membrane. (c) LLtoAA mutant Celsr1-GFP remaining at the plasma membrane of a basal cell undergoing mitosis. (d) LLtoAA Celsr1-GFP mutant is asymmetrically localized in basal cells in interphase. Bar=10µm. (e–f) Representative example of hair follicles from E17.5 K14-Celsr1WT-GFP (e) and K14Celsr1LLtoAA-GFP (f) transgenic founders. Shown are planar confocal sections through hair follicles labelled with E-Cad antibodies. Arrows show the direction of follicle growth. Bars= 50µm. Quantifications of hair follicle angles from transgenic embryos are shown to the right of their corresponding image (WT: n=396 hair follicles, 3 embryos; LLtoAA: n=386 hair follicles, 3 embryos). (g) Quantification of HF angles observed in K14-Celsr1-GFP transgenics at E15.5 (n=179 WT HFs, n=146 LLtoAA HFs) versus E17.5 (n=396 WT HFs, n=386 LLtoAA HFs). (h–i) Altered polarity surrounding mitotic cells expressing internalization defective Celsr1. Images show fluorescence intensity profiles of Celsr1 in planar confocal sections through basal layer of WT and LLtoAA transgenic backskins (red=high, blue=low). Centre cells are in cytokinesis while surrounding neighbours are in interphase. Quantification of Celsr1 intensity at the cell borders of interphase cells directly surrounding mitotic cells is shown to the right, where the average Celsr1 intensity along a border is plotted against its angle. Levels of Celsr1 were normalized to the minimum (0%) and maximum (100%) border intensities for each image field. Borders were binned into 5 degree increments and error bars denote s.e.m within bins. (h) In K14-Celsr1WT-GFP transgenics, A-P borders show highest Celsr1 intensity (n=88 borders). (i) The direction of highest Celsr1 intensity is more randomized in cells neighbouring Celsr1-LLtoAA expressing cells (asterisks; n=219 borders). Bar=10µm.

To evaluate the functional consequences of preventing mitotic internalization of Celsr1 on global tissue polarity, we examined hair follicle orientation, which is a key readout of epidermal PCP. In Celsr1WT-GFP expressing embryos, hair follicles oriented anteriorly and aligned along the A-P axis (Fig. 6e). By contrast, in patches of embryonic Celsr1LLtoAA-GFP transgenic backskin, hair follicles were misoriented. Interestingly, misoriented follicles tended to align locally with one another, and extend beyond the borders of Celsr1LLtoAA-expressing clones (Fig. 6f, S5b–c). Thus, Celsr1LLtoAA-GFP expression disrupted epidermal polarity non-autonomously and in a dominant manner.

We’ve previously shown that PCP in the basal layer is required for the proper A-P orientation of hair follicles. Consistently, hair follicles in Celsr1-GFP transgenics aligned in the direction of polarity of their surrounding basal epidermal cells (Fig. S5a–b). Since PCP proteins localize asymmetrically, but not strictly along the A-P axis, in Celsr1LLtoAA-GFP basal cells, underlying hair follicles polarize, but not always toward the anterior. This phenotype is distinct from Celsr1Crsh/Crsh and Vangl2Lp/Lp loss-of-function phenotypes, where basal epidermal cells lose A-P asymmetry and hair follicles grow straight downward2.

The Celsr1LLtoAA-GFP phenotype was more severe at E17.5 than E15.5 and was not due to altered rates of proliferation or apoptosis, which were similar to Celsr1WT-GFP transgenics (Fig. 6g, S6d–e). Although we cannot rule out that mutation of Celsr1’s dileucine motif might affect an unknown function of Celsr1, the normal behaviour of Celsr1LLtoAA-GFP in interphase, homotypic interactions, surface dynamics, asymmetric localization and Vangl2/ Fzd6 recruitment all suggest that the defect in hair follicle orientation arises from defective mitotic internalization. The results also bolster the evidence that mitotic internalization is critical for establishing and/or maintaining epidermal PCP. Consistent with this notion, polarity alterations were observed in neighbours of mitotic basal cells in Celsr1LLtoAA-GFP transgenics (Fig. 6h–i).

Discussion

We have identified mitotic internalization as a novel mechanism for maintaining global planar cell polarity in a proliferative tissue. We propose that internalization provides a mechanism to distribute asymmetrically localized PCP components equally to daughter cells and temporarily block cells from sending and receiving PCP signals while they round up and divide.

In the absence of wild-type Celsr1 in cultured keratinocytes, Celsr1LLtoAA clearly blocked internalization of its PCP associates. However, this did not happen in the presence of wild-type Celsr1, where Celsr1LLtoAA transgenic embryos showed no obvious defects in Vangl2 inheritance (Fig. S9). The fact that these mutant embryos nevertheless displayed marked non-autonomous disruption of planar cell polarity underscores the importance of Celsr1’s endocytic motif in the process, and indicates that at least one function of mitotic internalization is to modulate signalling.

PCP components are thought to transmit polarity cues by interacting across plasma membranes, and in Drosophila, Celsr1’s homolog Fmi is critical for cell-to-cell polarity transmission15,25–27. Taken together with our findings here, we posit that Celsr1 internalization should prevent cells from both sending and receiving PCP signals while they divide, thereby helping to maintain global alignment of polarity in a proliferative tissue. When an internalization defective Celsr1 is expressed, mitotic cells continue to signal and this aberrant directional information is propagated from cell to cell.

Polarized cells need a mechanism to maintain polarity when they divide. Single-layered epithelial cells orient their mitotic spindles parallel to the substratum to ensure that daughter cells maintain the apical-basal polarity of their parent20,28,29. Furthermore, many polarized cell types regulate spindle orientation to divide asymmetrically and generate cellular diversity30. We’ve discovered mitotic internalization as an additional mechanism for polarized epithelial cells to maintain planar polarity while they divide. To our knowledge, this is the first time components of a common pathway have been shown to internalize specifically when cells divide.

Despite its essential role in mouse epidermis, the mitotic internalization mechanism is not a universal feature of PCP31–34. In Drosophila sensory organ precursors, planar divisions with asymmetric daughter fates are oriented by cortically localized PCP proteins. Perhaps the difference is that basal epidermal cells don’t appear to depend on PCP for asymmetric cell fates. However, a recent study of PCP in the dividing Drosophila wing blade, also did not report internalization in mitotic cells35. While highly conserved in vertebrates, Celsr1’s internalization motif does not have a clear counterpart in Drosophila Fmi. It is presently unknown whether mitotic internalization is a conserved feature of PCP components in lower eukaryotes, and whether dividing cells have alternative mechanisms for preservation of tissue polarity.

While future studies will be necessary to resolve this issue, the highly proliferative nature of basal cells poses a particular challenge to maintain PCP. It is tempting to speculate that other highly proliferative tissues might maintain PCP by employing a mitotic internalization mechanism similar to the one we’ve unearthed in this study. If so, the internalization process may have evolved in vertebrates to suit the specialized needs of highly regenerative tissues.

Methods

Mouse lines and breeding

The K14 promoter, which drives expression in stratified epithelia, were used to generate transgenic mice expressing GFP-Vangl2. Mice were generated by conventional procedures after injection of linearized DNA in FVB mouse oocytes. Founder mice were determined by PCR genotyping and GFP-expression. Several transgenic lines mosaically expressing GFP-Vangl2 to different degrees were isolated and analysed. The GFP-Vangl2 protein was asymmetrically distributed in basal cells of all lines analysed. K14-driven expression of Vangl2 did not cause any obvious defects in skin differentiation or patterning. For experiments using K14-Celsr1-GFP and K14-Celsr1-LLtoAA-GFP transgenics, mosaically-expressing founder embryos were sacrificed at E17.5 and analysed. Looptail mutant mice (LPT/Le stock, Jackson Laboratories) were provided by M.W. Kelley.

Antibodies and immunofluorescence

For whole mount immunofluorescence, embryos were fixed 1hr in 4% formaldehyde. Backskins were dissected, permeablised 30 minutes in PBS+0.2% Triton (PBST), and blocked 1 hour in 2.5% fish gelatin, 2.5% normal donkey serum, 2.5% normal goat serum, 0.5% BSA, 0.2% Triton, 1X PBS. Primary antibodies were incubated for either 2 hours r.t. or overnight at 4°C at the following dilutions: Celsr12 (guinea pig 1:200), Vangl2 (rabbit 1:500, M. Montcoquiol), Fzd6 (goat 1:200, R&D Biosystems), E- and P-Cadherin (rat 1:100, M. Takeichi, RIKEN, Kobe), GFP (chicken 1:2000, AbCam), acetylated-tubulin (mouse 1:500, Sigma), β-tubulin (mouse 1:1000, Sigma), c-myc (mouse 9E10, 1:2000, Stratgene), Rab11 (rabbit 1:500, Zymed), caveolin (rabbit 1:1000, BD), GM130 (mouse 1:1000, BD), K5 (rabbit 1:1000, Fuchs Lab), Nectin-2 (rat 1:500, AbCam), Occludin (mouse 1:1000, Zymed), EEA-1 (1:500), phospho-HistoneH3-Ser10 (rabbit 1:1000, Upstate), active Caspase-3 (rabbit, 1:500, R&D Biosystems). Secondary antibodies coupled to Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen), Rhodamine Red X and Cy5 (Jackson Laboratories) were diluted 1:1000 and incubated 2hrs at r.t.

Image acquisition and quantification

Images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM510 laser-scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) and a 100× oil objective (N.A. 1.4). For whole mount imaging Z-stacks of 5–15 planes (0.5µm) were captured. Representative single Z-planes are presented. Images were recorded at 1024×1024 square pixels representing a 92µm × 92µm area. E17.5 whole mount hair follicle images were collected through a 10× (N.A. 0.8) objective and Z-stacks of 10–15 planes (2.5µm) were captured. Z-stacks were projected using ImageJ software. Images of cultured keratinocytes were obtained with an Axioplan microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) equipped with an Orca-ER camera (Hamamatsu) using Metamorph software. RGB images were assembled in Adobe Photoshop CS2 v. 9.0.2 and panels were labelled in Adobe Illustrator CS2 v. 12.0.1.

Quantification of co-localization between Celsr1 and E-Cadherin or trafficking markers in mitotic cells was performed in ImageJ using JACoP. M1 coefficients representing the percentage of Celsr1 co-localization per cell were calculated and plotted using Prism5 Software (GraphPad).

Quantifications of Celsr1 distribution during cytokinesis were performed as follows. Dividing cells were selected from sum-of-slices projection images of wild-type or Vangl2Lp/Lp epidermis, manually segmented in ImageJ on the basis of E-cadherin fluorescence, and imported into MATLAB. For each cell, Celsr1 fluorescence levels were normalized, and coordinates of the centroid and perimeter were computed. The angles of all pixels relative to the cell centre within 20 pixels (1.8um) of the periphery and above a 20% intensity threshold, determined empirically to include the majority of Celsr1-containing vesicles, were plotted in a rose diagram.

To quantify Celsr1 polarity in interphase cells, the mean intensity of Celsr1 along individual basal cells borders (manually identified by E-Cadherin labelling) was calculated using ImageJ software. The intensities were plotted against the angle of the cell borders relative to the A-P axis.

Time-lapse imaging

Keratinocytes were plated on 35mm glass bottom dishes coated with fibronectin and transfected with K14-Celsr1-GFP. 48 hours after transfection, cells were shifted to high calcium medium (1.2mM CaCl2) supplemented with 25mM HEPES buffer. Time-lapse images were acquired on a spinning disk confocal microscope (Improvision) with a 63× oil objective (N.A. 1.4). Z-stacks (10 slices, 0.5 um) were collected at 3 minute intervals for 3–12 hours, or until a cell had undergone mitosis. Z-stacks projections and movie editing was performed using Volocity software (Improvision). For TIRF, images were acquired on an inverted Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope with a 60× oil objective (N.A. 1.4) equipped with an Andor iXon camera. Keratinocytes stably expressing Celsr1-ΔN-GFP (WT or LLtoAA) we transfected with DsRed-Clathrin. Green and Red channels were acquired sequentially every 2–3s for 7–15min.

Cell culture

Mouse keratinocytes were cultured and maintained in E-media supplemented with 15% serum and 0.05mM Ca2+. For Celsr1GFP, Cherry-Vangl2 and Fzd6-Cherry transfection experiments, keratinocytes were plated onto fibronectin-coated coverslips in 12-well dishes (70,000 cells/well). 12–24hrs after plating, cells were transfected with 800ng DNA using FuGENE transfection reagent (Roche). 24hrs after transfection, cells were shifted to high Ca2+ (>1mM) E-media for 8 hours, then fixed and processed for immunofluorescence. Mitotic stages were determined by nuclear or spindle morphology, which were labelled by DAPI or tubulin staining.

Constructs, cloning and mutagenesis

Wild type K14-Celsr1-GFP, K14-Fzd6-Cherry and K14-Cherry-Vangl2 have been described previously2 as well as K14-ECad-GFP (A. Vaezi and E. Fuchs). Celsr1ΔN-GFP was generated by fusing the signal peptide of Celsr1 (amino acids 1 to 33) to amino acids 2067 to 3034 and cloning into a lentiviral vector pLentiPGKMCSSma1 (constructed and generously donated by E. Vladar, Axelrod Lab). For stable cell lines, keratinocytes were infected with retrovirus containing Celsr1ΔN-GFP under the K14 promoter (pSINRevK14PGKhyg-Celsr1ΔN-GFP) and selected for expression with 25ug/ml hygromycin. To generate the E-Cadherin-Celsr1 C-terminal fusions Spe1-Bgl2 E-Cad fragments were ligated to Bgl2-Hind3 Celsr1 fragments and cloned into Nhe1 and Hind3 sites of the pEGFPN1 vector (Clontech). For E-Cadherin-Celsr1ΔN-GFP amino acids 1 to 704 of E-Cadherin were fused to amino acids 2061 to 3034 of Celsr1. For E-Cadherin-Celsr1CT, amino acids 1 to 734 of E-Cadherin were fused to amino acids 2716 to 3034 of Celsr1. Mutation of Celsr1 L2748 and L2749 to alanine, and S2741, T2743-4, T2747, T2750, S2752 was performed by PCR overlap extension mutagenesis. DsRed-Rab5WT was kindly provided by R.E. Pagano and DsRed-Clathrin by T. Kirchhausen.

Transferrin and lysotracker uptake assays

To label early, late and recycling endosomes, fluorescently labelled transferring (AlexaFluor546-transferrin, Invitrogen) was diluted to 5ug/ml in E-media and added to cultured keratinocytes plated on fibronectin-coated coverslips. After 1 hour incubation cells were rinsed 3× in PBS and fixed for 10 minutes in 4% formaldehyde. To label lysosomes, keratinocytes were incubated for 90 minutes in E-media containing 100uM lysotracker-546 (Invitrogen Molecular Probes).

Quantification of hair follicle orientation

Whole mount backskins were fixed and stained as described above with E-Cadherin and K5 antibodies to highlight hair follicle morphology. Backskins were mounted dermis-side up and imaged using a 10X objective. Hair follicle angles relative to the anterior-posterior axis were measured using ImageJ software. E-Cadherin staining was used to determine each hair follicle’s central axis. Data were analysed and plotted using Prism5 and Origin7.5 software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Stokes for her assistance in the mouse facility; Mirelle Montcouquoil for Vangl2 antibodies; and Eszter Vladar and Jeff Axelrod for sharing the lenti-Celsr1Δ-GFP construct. We thank Sandy Simon lab members Laura Macro and Claire Atkinson for advice and constructs for TIRF imaging. We are grateful to Scott Williams for retroviral vectors and technical assistance, Ben Short and members of the Fuchs laboratory for discussions and reading of the manuscript. We thank Alison North and Kaye Thomas at the RU Bioimaging Resource Center for assistance with image acquisition, and the Comparative Biology Center (CBC) for their help in veterinary care. D. D. is the recipient of a K99 Award from the National Institutes of Health. E.F. is an investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Work was supported by the HHMI and the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

E.F. and D.D. designed experiments. D.D. performed the experiments and analysed their raw data. D.O. performed injections for generation of transgenic founder animals. E.H. performed quantitative analyses of image data in Figure 3. D.D. and E.F. wrote the paper.

Author Information

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Guo N, Hawkins C, Nathans J. Frizzled6 controls hair patterning in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9277–9281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402802101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devenport D, Fuchs E. Planar polarization in embryonic epidermis orchestrates global asymmetric morphogenesis of hair follicles. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1257–1268. doi: 10.1038/ncb1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simons M, Mlodzik bM. Planar cell polarity signaling: from fly development to human disease. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:517–540. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strutt DI. Asymmetric localization of frizzled and the establishment of cell polarity in the Drosophila wing. Mol Cell. 2001;7:367–375. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bastock R, Strutt H, Strutt D. Strabismus is asymmetrically localised and binds to Prickle and Dishevelled during Drosophila planar polarity patterning. Development. 2003;130:3007–3014. doi: 10.1242/dev.00526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Usui T, et al. Flamingo, a seven-pass transmembrane cadherin, regulates planar cell polarity under the control of Frizzled. Cell. 1999;98:585–595. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Axelrod JD. Unipolar membrane association of Dishevelled mediates Frizzled planar cell polarity signaling. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1182–1187. doi: 10.1101/gad.890501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tree DR, et al. Prickle mediates feedback amplification to generate asymmetric planar cell polarity signaling. Cell. 2002;109:371–381. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montcouquiol M, et al. Asymmetric localization of Vangl2 and Fz3 indicate novel mechanisms for planar cell polarity in mammals. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5265–5275. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4680-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Guo N, Nathans J. The role of Frizzled3 and Frizzled6 in neural tube closure and in the planar polarity of inner-ear sensory hair cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2147–2156. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4698-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, et al. Regulation of polarized extension and planar cell polarity in the cochlea by the vertebrate PCP pathway. Nat Genet. 2005;37:980–985. doi: 10.1038/ng1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deans MR, et al. Asymmetric distribution of prickle-like 2 reveals an early underlying polarization of vestibular sensory epithelia in the inner ear. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27:3139–3147. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5151-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinson CR, Adler PN. Directional non-cell autonomy and the transmission of polarity information by the frizzled gene of Drosophila. Nature. 1987;329:549–551. doi: 10.1038/329549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor J, Abramova N, Charlton J, Adler PN. Van Gogh: a new Drosophila tissue polarity gene. Genetics. 1998;150:199–210. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.1.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawrence PA, Casal J, Struhl G. Cell interactions and planar polarity in the abdominal epidermis of Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:4651–4664. doi: 10.1242/dev.01351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strutt D, Strutt H. Differential activities of the core planar polarity proteins during Drosophila wing patterning. Dev Biol. 2007;302:181–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Badea T, Nathans J. Order from disorder: Self-organization in mammalian hair patterning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19800–19805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609712104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strutt H, Strutt D. Differential stability of flamingo protein complexes underlies the establishment of planar polarity. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1555–1564. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker J, Garrod D. Epithelial cells retain junctions during mitosis. J Cell Sci. 1993;104(Pt 2):415–425. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.2.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reinsch S, Karsenti E. Orientation of spindle axis and distribution of plasma membrane proteins during cell division in polarized MDCKII cells. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:1509–1526. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.6.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smart IH. Variation in the plane of cell cleavage during the process of stratification in the mouse epidermis. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:276–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1970.tb12437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zerial M, McBride H. Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:107–117. doi: 10.1038/35052055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boucrot E, Kirchhausen T. Endosomal recycling controls plasma membrane area during mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7939–7944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702511104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonifacino JS, Traub LM. Signals for sorting of transmembrane proteins to endosomes and lysosomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:395–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen WS, et al. Asymmetric homotypic interactions of the atypical cadherin flamingo mediate intercellular polarity signaling. Cell. 2008;133:1093–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu J, Mlodzik M. The frizzled extracellular domain is a ligand for Van Gogh/Stbm during nonautonomous planar cell polarity signaling. Developmental cell. 2008;15:462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu J, Mlodzik M. A quest for the mechanism regulating global planar cell polarity of tissues. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernandez-Minan A, Martin-Bermudo MD, Gonzalez-Reyes A. Integrin signaling regulates spindle orientation in Drosophila to preserve the follicular-epithelium monolayer. Curr Biol. 2007;17:683–688. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaffe AB, Kaji N, Durgan J, Hall A. Cdc42 controls spindle orientation to position the apical surface during epithelial morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:625–633. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siller KH, Doe CQ. Spindle orientation during asymmetric cell division. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:365–374. doi: 10.1038/ncb0409-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segalen M, Bellaiche Y. Cell division orientation and planar cell polarity pathways. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:972–977. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gho M, Schweisguth F. Frizzled signalling controls orientation of asymmetric sense organ precursor cell divisions in Drosophila. Nature. 1998;393:178–181. doi: 10.1038/30265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu B, Usui T, Uemura T, Jan L, Jan YN. Flamingo controls the planar polarity of sensory bristles and asymmetric division of sensory organ precursors in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1247–1250. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80505-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bellaiche Y, Beaudoin-Massiani O, Stuttem I, Schweisguth F. The planar cell polarity protein Strabismus promotes Pins anterior localization during asymmetric division of sensory organ precursor cells in Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:469–478. doi: 10.1242/dev.00928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aigouy B, et al. Cell flow reorients the axis of planar polarity in the wing epithelium of Drosophila. Cell. 2010;142:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.