Abstract

Purpose

p53 as a prognostic and predictive factor in early stage breast cancer, has had mixed results. We studied p53 protein expression, by immunohistochemistry, in a randomized clinical trial of stage II patients treated with adjuvant doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide with or without paclitaxel (CALGB 9344, INT0148).

Patients and Methods

Epithelial p53 expression was evaluated using two immunohistochemical antibodies (DO7 and 1801) in formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissue from patients with node positive breast cancer who were randomized to four cycles of cyclophosphamide and one of three doses of doxorubicin (60, 75, or 90 mg/m2) (AC) and to receive four subsequent cycles of paclitaxel (T) or not. Prognostic and predictive value of p53 protein expression was assessed, independent of treatment assignment, for escalating doses of doxorubicin or addition of T with endpoints of RFS and OS.

Results

1887 of 3121 patient specimens treated on C9344 were obtained, passed quality control and evaluated for p53 expression. Expression was 23% and 27% for mAbs 1801 and D07 respectively, with 92% concordance. In univariate analysis, p53 positivity was associated with worse OS with either antibody, but only p53 staining with monoclonal antibody1801 had significantly worse RFS. In multivariate analysis, p53 was not predictive of RFS or OS from either doxorubicin dose escalation or addition of paclitaxel regardless of the antibody.

Conclusion

Nuclear staining of p53 by immunohistochemistry is associated with worse prognosis in node positive patients treated with adjuvant doxorubicin-based chemotherapy, but is not a useful predictor of benefit from doxorubicin dose escalation or the addition of paclitaxel.

Introduction

p53 is a vital regulator of genomic stability by controlling the cell cycle and inducing apoptosis when cell damage is beyond repair1-3. The p53 gene is located on the short arm of chromosome 17 (17p13.1) and encodes a 375 amino acid nuclear phosphoprotein that prevents propagation of genetically altered cells4. In normal cells, p53 protein has a very short half-life, expressed in minutes, by virtue of ubiquitylation and proteosome degradation, mediated by MDM25,6. However, missense mutations within the p53 gene result in protein that is stabilized through posttranscriptional modification and accumulation in the cell nucleus.

p53 protein expression has been related to poor outcome in breast cancer1,7-16. However its utility as a prognostic marker is controversial, and p53 determination is not recommended for routine clinical use in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients2,3,6,17-24. The mixed results for epithelial p53 and breast cancer prognosis may reflect in part the pleiotropic functions of p53, which are mediated by different domains of the protein. In this regard, p53 might confer both prognostic and predictive effects, depending on whether and what systemic therapy is applied. Predictive factors are best considered in the context of prospective randomized trials that have addressed the specific utility of the treatment in question.25,26 Therefore, studies that do not take systemic therapies into consideration are likely to be highly confounded.

The Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) has previously reported that increasing doses of a doxorubicin-based regimen (doxorubicin doses from 30-60 mg/m2) improved both relapse free and overall survival (RFS, OS, respectively)27. The results from a subsequent study, CALGB 9344 (North American Intergroup 0148), showed no evidence of benefit from further escalation of doxorubicin above 60 mg/m2, when applied with a fixed dose of cyclophosphamide (“AC” chemotherapy), but a statistically significant and clinically important benefit with addition of paclitaxel after AC28. We have also previously reported that HER2 amplification and/or over-expression, is a strong predictive factor of outcome in patients receiving paclitaxel after AC in C934429. We hypothesized that p53 abnormalities, as indicated by staining with immunohistochemistry might also predict benefit from either increasing doses of doxorubicin or from addition of paclitaxel after four cycles of AC. In the present study, we report the results of analysis of C9344 according to p53 protein expression as determined by IHC with two different monoclonal antibodies (mAbs).

Methods

Patients

The CALGB Study 9344, a Phase III Intergroup Study (INT-0148, CALGB 9344, ECOG C9344, NCCTG 94-30-51, and SWOG 9410) was the source of the patient material used in this analysis. Prior analyses of the main effects and of subgroup analyses according to HER2 status have been published by the CALGB28,29 and others30. CALGB/INT 0148 was a 2×3 factorial design in which patients were randomly assigned to one of six possible treatment combinations. All patients received four cycles of doxorubicin (Adriamycin®, A) and cyclophosphamide (C) given every three weeks. The latter was given at a fixed dose of 600 mg/m2, while patients were randomly assigned to one of three doses of doxorubicin (60, 75, or 90 mg/m2). All patients were also randomly assigned to either receive four cycles of paclitaxel (Taxol®, T) every three weeks following the AC, or no further chemotherapy. A total of 3121 patients were accrued to C9344. All patients signed written informed consent and the protocol was approved through individual institutional review boards.

Tissue procurement and utilization

Approximately 90% of patients accrued to C9344 provided written informed consent for collection and submission of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks or unstained tissue sections on slides. The informed consent was approved by all participating institutional review boards. Permission to receive and study the individual tissue sections was provided by the institutional review boards of the respective investigational laboratories. All processing, staining, and statistical evaluation was prospectively described in a written protocol (CALGB 159905). Tissue specimens from the patients' primary institution were submitted to the Pathology Coordinating Office (PCO) of each of the participating groups and then submitted for storage and processing at the CALGB PCO. Sections were logged, coded and reviewed for sufficient invasive cancer by the study pathologist (IB) and sent to two different laboratories (ADT and LGD) for p53 analysis using two different but previously described antibodies (p1801 and DO7 respectively) and methodology. Standard sections were prepared using formalin fixed, paraffin embedded sections cut on a microtome at standard 5 or 6-micron sections and deparaffinized and placed on charged slides.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) Analysis

p53 status was determined by IHC analyses with two separate monoclonal antibodies: p1801 (Genesis Bio-Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Tenafly NJ) and D07 (Biogenix, San Ramon, CA).

mAB p1801

IHC staining and analysis of mAB p1801 was performed in the laboratory of Dr. Ann Thor, on formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded sections as described previously 12,.

mAB DO7

IHC staining and analyses of mAB D07 was performed in the laboratory of Dr. Lynn Dressler using a steam antigen retrieval system. Monoclonal antibody D07 was prepared in a 1:1000 dilution and formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded sections cut at 5 microns were prepared on charged slides, stained with the diluents and prepared according to manufacturer's guidelines (followed instructions in package insert).

All slides prepared were scored by pathologists (ADT and JFL). A visual score of 10% or greater positive nuclear staining of invasive cancer cells was considered positive for both antibody analyses, a cutoff used for previous CALGB p53 studies 19. All IHC analyses were performed blindly at the respective laboratories and data were submitted to the CALGB statistical center for correlation with clinical outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by the CALGB statistical center (GB) using the SAS software package. The primary objective of this study was to evaluate whether RFS differed based on p53 protein expression status, and if there was a detectable interaction between p53 protein status and either escalating doses of doxorubicin (60, 75, or 90 mg/2 per cycle) when administered with a fixed dose of cyclophosphamide, and/or between p53 protein status and administration of four cycles of paclitaxel after AC chemotherapy. Correlation of p53 staining with OS was a secondary objective.

To preserve tissue and resources, a sampling scheme was prospectively developed to test the relative worth of potential predictive markers in CALGB 9344, including p53 protein expression as described29. By direction of the statistical center of the PCO an initial sample study was recommended. First, a test set of specimens was randomly requested from 750 of the 3121 patients who participated in C9344. This set was balanced, compared to the remaining patients from whom specimens were not requested, on potential prognostic factors, such as number of positive lymph nodes, ER status, age, and randomized treatment assignment. This first randomly selected group of tumors was assayed by both the mAb p1801 and the mAb DO7. Two subsequent sets of specimens, each containing 800 cases, were requested. These sets were distinct from each other, and each was stained with one of the two antibodies.

The Chi-Square test was used for comparing patient characteristics of those with p53 assessment to those without. The log-rank test compares two or more survival distributions. Cohen's Kappa Coefficient was used to show level of agreement between the two methodologies used to assess p53 (IHC with mAbs D07 and 1801). McNemar's test was used to compare levels of disagreement between the methods. Cox Proportional Hazard Regression models were used to determine significance of the interaction of treatment (doxorubicin dose escalation; addition of paclitaxel) and p53 protein status on RFS and OS after adjusting for clinical characteristics including number of positive lymph nodes, tumor size, hormone receptor status, patient age upon admission to study, dose of doxorubicin and administration of paclitaxel. Kaplan-Meier survival curves visually displayed the interaction effect of either doxorubicin or paclitaxel and p53 status. Results of this study are presented in accordance with REMARK criteria for tumor marker results reporting 31

As part of the quality assurance program of the CALGB, members of the Audit Committee visit all participating institutions at least once every three years to review source documents. The auditors verify compliance with federal regulations and protocol requirements, including those pertaining to eligibility, treatment, adverse events, tumor response, and outcome in a sample of protocols at each institution. Such on-site review of medical records was performed for a subgroup of 14 patients (4%) of the 3170 patients under this study.

Results

Patient selection and demographics

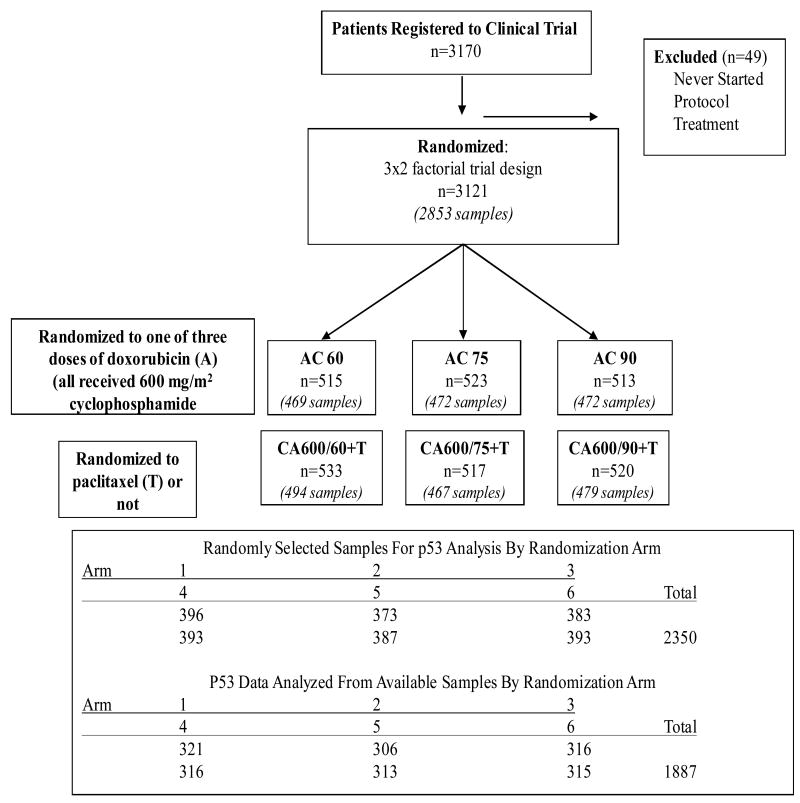

A total of 3121 patients were enrolled into the C9344 trial and approximately 90% (2880) of these patients had representative paraffin blocks or unstained slides of their tumors submitted to the PCO and were eligible for inclusion in this study. From this accrued group, three separate sets of specimens were requested as described in Methods. Of the 750 specimens in Set 1, 641 and 629 were available, passed internal quality control (QC) for IHC staining, and were successfully evaluated for p53 by antibodies 1801 and D07, respectively. Of the eight hundred (800) specimens that were requested for each of the second and third sets, 680 and 566 were available, passed QC, and were successfully analyzed for 1801 and D07, respectively. In total, 1321 (85% of requested, 42% of total accrued) and 1195 (77% of requested, 38% of accrued) specimens were successfully analyzed for staining with mAbs 1801 and D07, respectively, and, 1887 patients were evaluable by at least one of the mAbs (1801 or D07). These cases represent the analyzable cohort (Table 1). These results are also provided in the REMARK diagram (Figure 1). The median follow-up for the 1887 patients was 11.2 years (134 months). Of these patients, 671 (36%) have died while 819 (43%) experienced failure events (recurrence or metastasis). There were no statistically significant or appreciable differences, in any of the demographic or outcomes data between those cases selected for the current study and the total group of patients, or those not selected, however there was a difference in p value between RFS and OS (RFS, p=0.075 vs. OS, p=0.053) (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient Characteristics: Comparison of all patients enrolled in CALGB 9344 vs. cases selected for p53 IHC staining vs. those not selected.

| All Treated Patients n=3121 | Patients with p53 by D07 or 1801 n=1887 | Others n=1234 | p-value2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Treatment Arm of 9344 | 0.99 | |||

| CA 600 / 60 + Paclitaxel | 533 (17)1 | 321 (17) | 212 (17) | |

| CA 600/ 60 | 515 (16) | 306 (16) | 209 (17) | |

| CA 600/ 75 + Paclitaxel | 517 (17) | 316 (17) | 201 (16) | |

| CA 600/ 75 | 523 (17) | 316 (17) | 207 (17) | |

| CA 600 / 90 + Paclitaxel | 520 (17) | 313 (17) | 207 (17) | |

| CA 600 / 90 | 513 (16) | 315 (17) | 198 (16) | |

|

| ||||

| Age | 0.37 | |||

| < 40 | 636 (20) | 376 (20) | 260 (21) | |

| 40-49 | 1248 (40) | 741 (39) | 507 (41) | |

| 50-59 | 843 (27) | 530 (28) | 313 (25) | |

| 60+ | 394 (13) | 240 (13) | 154 (12) | |

|

| ||||

| Race | 0.53 | |||

| White | 2611 (84) | 1586 (84) | 1025 (83) | |

| Hispanic American | 127 (4) | 82 (4) | 45 (4) | |

| African American | 296 (9) | 160 (9) | 136 (11) | |

| Asian | 52 (2) | 34 (2) | 18 (1) | |

| Other | 35 (1) | 25 (1) | 10 (1) | |

|

| ||||

| Menopausal Status | 0.33 | |||

| Premenopausal | 1925 (62) | 1151 (61) | 774 (63) | |

| Peri / Postmenopausal | 1196 (38) | 736 (39) | 460 (37) | |

|

| ||||

| Pathological Tumor Size* | 0.072 | |||

| ≤ 2 cm | 1096 (35) | 639 (34) | 457 (37) | |

| > 2 cm | 2008 (65) | 1237 (66) | 771 (63) | |

|

| ||||

| ER Status* | 0.66 | |||

| Positive | 1840 (59) | 1120 (60) | 720 (59) | |

| Negative | 1263 (41) | 759 (40) | 504 (41) | |

|

| ||||

| Number Pos Lymph Nodes* | 0.81 | |||

| 1-3 | 1450 (46) | 885 (47) | 565 (46) | |

| 4-9 | 1310 (42) | 784 (42) | 526 (43) | |

| 10+ | 360 (12) | 217 (12) | 143 (12) | |

|

| ||||

| Primary Treatment | 0.71 | |||

| mastectomy | 2177 (70) | 1331 (71) | 846 (69) | |

|

| ||||

| 5-yr survival | Log-rank p-value | |||

| Relapse-free | 67% (66-69)3 | 69% (67-71) | 66% (63-68) | 0.075 |

| Overall | 78% (77-80) | 79% (77-81) | 76% (74-79) | 0.053 |

Number (% of all)

Comparing cases selected vs. those not selected

Percent free of event (95% Confidence Interval)

Indicates that there were a small number of patients where these results were not known.

Figure 1.

REMARK diagram of case selection for p53 staining. Treatments: C=Cyclophosmide, A=Doxorubicin, T=paclitaxel. Arm/Treatment: 1=CA 600/60+T; 2=CA 600/60; 3=CA 600/75+T; 4=CA 600/75; 5=CA 600/90+T; 6=CA 600/90.

P53 protein expression

Of the 629 specimens successfully stained with both antibodies in set 1, 155 (25%) and 180 (29%) were p53 immuno-positive (as defined in Methods) for mAbs 1801 or D07, respectively (Table 2). Concordance between staining for mAbs 1801 and D07 was evaluated and seen in 580/629 cases (92.2%) with a kappa statistic of 80% ±2.7%. (Table 2). Of the discordant cases, more cases were p53 positive using the DO7 antibody and negative with the p1801 antibody than vice versa (76% vs. 24% respectively), (McNemar's Test; p=0.0004).

Table 2.

Comparison of P53 staining by mAb 1801 and mAb DO7.

| p53 D07 | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative1 | Positive | ||||||

| p53 1801 | Negative | 437 | (69%)2 | 37 | (6%) | 474 | (75%) |

| Positive | 12 | (2%) | 143 | (23%) | 155 | (25%) | |

| Total | 449 | (71%) | 180 | (29%) | 629 | (100%) | |

Negative <10% nuclear staining; Positive ≥10% nuclear staining.

Number of patients (% of total)

p53 protein expression and outcomes

p53 Staining as a Prognostic Factor

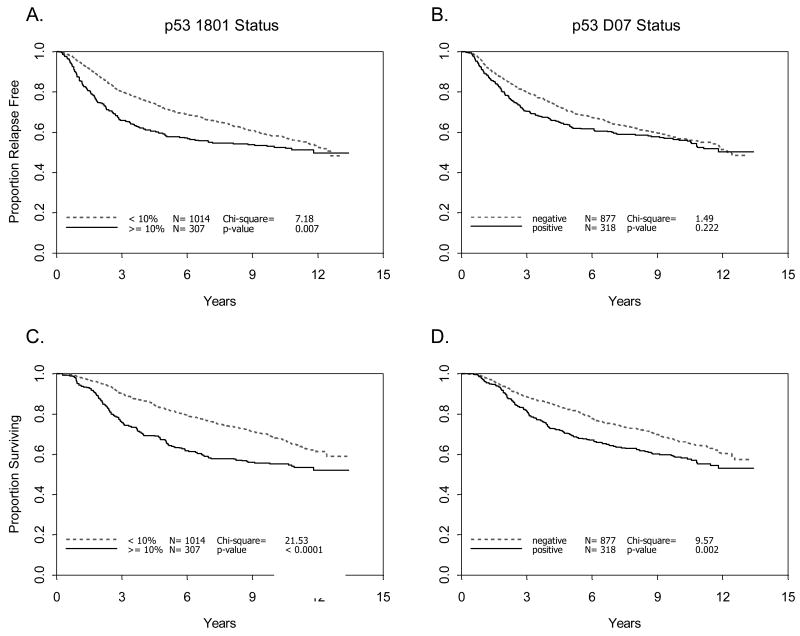

When all cases were analyzed, irrespective of treatment assignment, p53 staining was found to be an adverse prognostic factor (Figure 2). Association of p53 staining with worse RFS was significant for mAB p1801 alone (p=0.007), but not for mAb D07 alone (p=0.22), and only marginally when mAbs 1801 and D07 were considered together (p=0.05). Univariate analysis of p53 positivity was associated with significantly worse OS when analyzed by either antibody alone (mAb p1801, p<0.0001; mAb D07, p=0.002), or both together (p<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Relapse free and overall survival by p53 status. Relapse free (A, B) and overall survival (C, D) were determined according to p53 staining with either mAb 1801 (A, C) or D07 (B, D) in 1195 patients with node positive breast cancer treated within CALGB 9344 (see Methods). Negative: <10% nuclear staining. Positive: ≥10% nuclear staining.

p53 Staining as a Predictive Factor

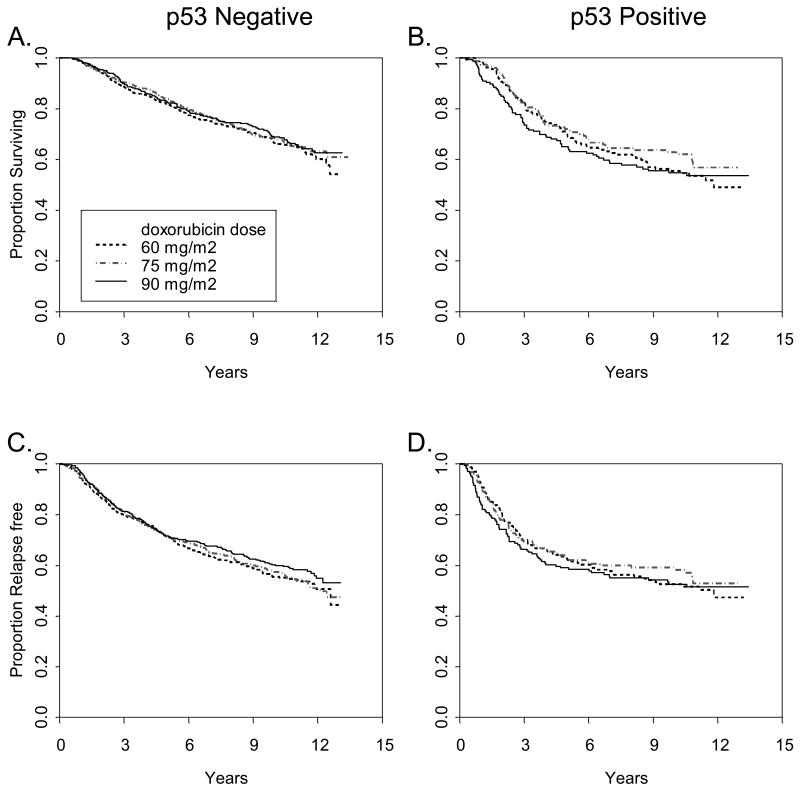

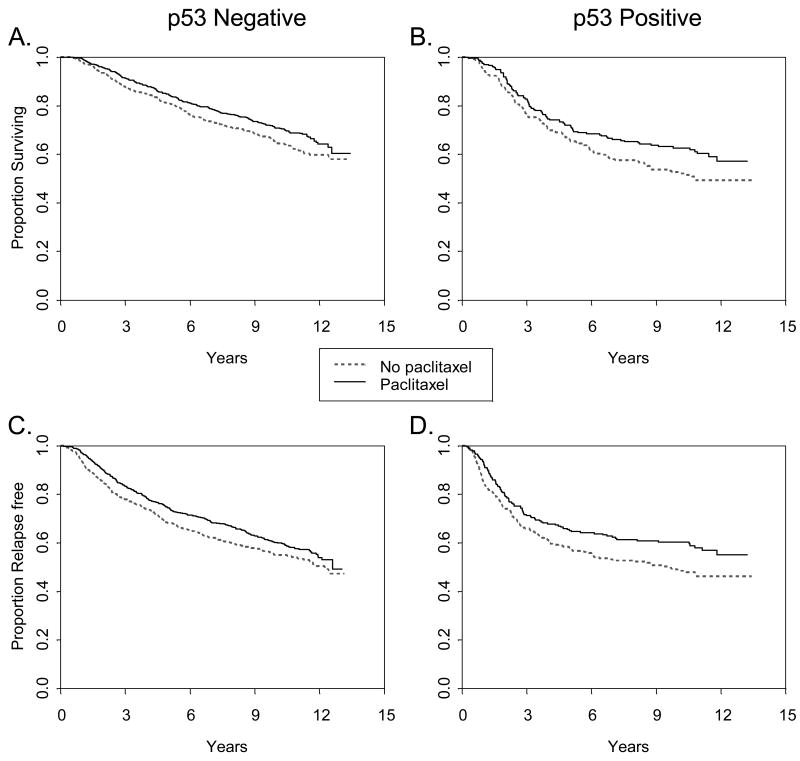

In multivariate analysis there was no significant interaction between p53 protein expression status and dose of doxorubicin (Figure 3A) or with addition of paclitaxel (Figure 3B) with respect to either RFS or OS. (Table 3). There was no apparent relationship between dose level of doxorubicin and p53 status or between paclitaxel and p53 status by IHC. The benefit from paclitaxel seen in the overall cohort was equally observed in both p53 positive and negative cases, regardless of the antibody used.

Figure 3.

Figure 3A. Relapse free and overall survival according to p53 status by doxorubicin treatment arm. Relapse free (A, B) and overall (C, D) survival were determined according to p53 staining with both mAb 1801 and D07 in 1887 patients with node positive breast cancer treated within CALGB 9344. Positive (B,D), or negative (A, C) refers to both mAb 1801 and D07.

Figure 3B. Relapse free and overall survival according to p53 status by paclitaxel treatment arm. Overall (A, B) and relapse free survival (C, D) were determined according to p53 staining with both mAb 1801 and D07 in 1887 patients with node positive breast cancer treated within CALGB 9344. Positive (B, D) refers to both mAb 1801 and D07 positive; negative (A, C) is otherwise.

Table 3.

Survival according to p53 status. Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards model for prediction of relapse-free survival and overall survival by p53 1801 or p53 D07 status and paclitaxel interaction; n=1868 of 1887 patients with p53 evaluations are included in this model. (p53 status is considered positive if either D07 or 1801 is positive.)

| Relapse Free Survival | Overall Survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (Confidence Limits) | Likelihood-Ratio Tests1 Chi-Square | p-value | Hazard Ratio (Confidence Limits) | Likelihood-Ratio Tests1 Chi-Square | p-value |

| Number of Positive Nodes (square root) | 1.43 (1.33-1.54) | 94.8 | <.0001 | 1.45 (1.34-1.57) | 87.9 | <.0001 |

| Tumor Size (≤ 2 vs > 2 cm) | 1.45 (1.24-1.70) | 21.7 | <.0001 | 1.49 (1.25-1.78) | 20.0 | <.0001 |

| ER status (pos vs neg) | 0.70 (0.60-0.81) | 22.6 | <.0001 | 0.58 (0.49-0.68) | 44.7 | <.0001 |

| Age at study entry | 0.99 (0.99-1.01) | 0.30 | 0.58 | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 1.09 | 0.30 |

| Paclitaxel (Yes vs No) | 0.84 (0.72-0.99) | 9.84 | 0.0017 | 0.80 (0.67-0.97) | 11.2 | 0.0008 |

| p53 1801 or D07 (either positive vs other) | 1.19 (0.96-1.47) | 1.14 | 0.29 | 1.34 (1.07-1.68) | 7.04 | 0.008 |

| Interaction of paclitaxel and p53 | 0.83 (0.61-1.14) | 1.35 | 0.25 | 0.87 (0.63-1.22) | 0.64 | 0.42 |

We also performed several exploratory analyses. Previously, we had reported that the addition of paclitaxel to AC adjuvant chemotherapy appeared to be of little, if any, value in patients who participated in CALGB 9344 who had ER positive, HER2 negative cancers 29. In the current study, we did not detect any statistically significant interactions between p53 and the addition of paclitaxel by ER-status, for either RFS or OS. Also, in an exploratory Cox proportional hazards model analysis, we did not observe a significant interaction of p53 status and dose of doxorubicin in predicting RFS, interaction (p=0.69), when adjusting for co-variates.

Discussion

In this study, we observed that while p53 protein expression, presumably reflecting p53 abnormality, was associated with worse overall survival, it did not predict benefit from escalating doses of doxorubicin above the standard used 60 mg/m2, or from the addition of paclitaxel in patients with node positive, newly diagnosed breast cancer. This observation was made regardless of IHC methodologies using either mAbs 1801 or D07 which collectively represent the most frequently used p53 IHC antibodies currently in standard everyday practice.

Our observation of a marginal prognostic and non-predictive effect of p53 in this study differs from some3,5,14,20,21 but not all prior investigations 10,23,30. However our data represent a strong and definitive statement due to the large cohort and lengthy follow-up presented. Indeed, in our own preliminary results from CALGB protocol 8541, we observed that p53 staining with mAb p1801, especially when combined with HER2 status, was predictive of benefit from increasing doses of doxorubicin from very low (30 mg/m2) to what is now considered standard (60 mg/m2) dose 19. Prior to this current study, we hypothesized that positive p53 staining, coupled with HER2 positivity, might predict for even higher escalation of doxorubicin dose, which was escalated up to 90mg/m2 in CALGB 9344. However, we did not observe such an effect in this large correlative study.

There are a number of possible reasons why we did not detect a more substantial effect of p53. Overall, the literature supports our observation (Figure 2) that p53 expression is associated with more aggressive behavior in many cancers, including breast cancer. However, previous studies have provided highly contradictory results regarding the predictive role of p53 expression for beneficial effects of chemotherapy. Our data, taken from a prospective randomized clinical trial, provide high levels of evidence that p53 expression does not predict benefit from either escalation of doxorubicin dose above 60 mg/m2, perhaps because this represents an optimal or threshold dose for this agent, or addition of paclitaxel after four cycles of AC chemotherapy. It is possible that our data represent a false negative observation. However, in this regard, we have previously reported a substantial and significant predictive effect for benefit from addition of paclitaxel, but not doxorubicin dose escalation, in patients whose tumors are either ER negative, or HER2 positive, or both 29, suggesting that this dataset is adequately powered to detect an important biomarker/treatment interaction.

Technical concerns may also account for why we did not observe any association between p53 positivity and benefit from doxorubicin dose escalation or paclitaxel. In our study, we assessed p53 by immunohistochemistry. We detected similar, although not identical, effects with each of the two antibodies we incorporated into this study (mAbs D07 and 1801), which have been widely used and validated in prior studies, including CALGB 854119. It is noteworthy that for this study we report only epithelial p53 staining patterns, in particular nuclear staining characteristics, and did not report stromal staining characteristics of invasive carcinomas relative to p53 staining which has recently been observed and noted to be of clinical significance34. Several studies have demonstrated that IHC staining for p53 does not always detect all mutations, it does not identify all deletions, and it may detect stabilized, but wild type, p53 protein 7,33. p53 is a highly pleiotropic molecule, with several different cellular and biologic functions and each of these is associated with one or more different domains in the protein4,19. Of the two antibodies used in this study, the mAb1801 covers epitopes 32-79, while DO7 covers 37-45. 35 Most mutations of p53 occur within exons 4-8, which are generally the areas of the proteins for which these two antibodies test, although of course it is possible that either or both antibodies might not detect protein with specific mutations in these regions.

IHC staining may miss important activating or inactivating abnormalities within the p53 gene that might mediate sensitivity or resistance to all, or specific types, of chemotherapies. In addition, since the functions of p53 include, but are likely not limited to, ubiquitylation and sumoylation, there are various pathways through which this complex tumor suppressor carries out its functions. Furthermore, certain p53-mediated pathways may differ among even similar appearing tumor types and in their response to various therapeutic agents. 32

Although p53 gene sequencing might provide additional or alternative results regarding prediction of benefit from doxorubicin dose or addition of paclitaxel, this study was not designed nor intended to be a comparative analysis of IHC vs gene sequencing. Gene sequencing is not a practical everyday test that can be performed readily in most labs and it is currently cost prohibitive. Moreover analysis of gene sequencing using formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissue is not optimal and results may be unpredictable. Most studies to date using gene sequencing have been of relatively small cohorts from single institutions in which processing methods can be more easily standardized and regulated. The likelihood of maintaining such stringent quality control standards in a multi-institutional group study would be precarious at best. Finally, sequencing studies may not necessarily identify small nuances among the myriad of potential alternate pathways that continue to be identified in sporadic cases.

In conclusion, our data, produced from archived specimens from a prospective randomized clinical trial, do not support routine use of IHC to determine epithelial p53 protein status in patients who will benefit from higher doses of doxorubicin those that are recommended for standard clinical care, nor from taxane-based adjuvant chemotherapy. We did observe statistically significant prognostic differences overall for p53 positivity. Although these differences suggest clinical validity of p53 staining, these findings do not have clinical utility other than to predict a more aggressive tumor 26,33. The magnitude of differences in OS between those for whom p53 was positive nor negative was insufficiently substantial to change practice,, nor did p53 negativity did not identify a group of patients with such a favorable prognosis that further therapy, if available, would not be indicated. Nevertheless, they do suggest that p53 plays an important role in the biology of breast cancer and for that reason is felt to still be an important mechanism in the pathway of carcinogenesis and worthy of continued study in order to further our understanding of cancer genesis and biology.

Statement of Translational Relevance.

The findings of this study will further refine the direction of evaluation and treatment of new breast cancers, specifically whether or not to include p53 in initial evaluation as a breast prognostic factor.

Acknowledgments

The research for CALGB 9344 was supported, in part, by grants from the National Cancer Institute (CA31946) to the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (Monica M. Bertagnolli, MD, Chair) and to the CALGB Statistical Center (Daniel J. Sargent, PhD, CA33601). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute

The authors would like to acknowledge the Pathology Coordinating Offices of the respective participating cooperative groups (CALGB, EORTC, NCCTG, and SWOG), and in particular Laura Monovich and Scott Jewell, Ph.D. for their tireless efforts in cataloguing and preparing tissues for this study. Also to Janell Markey for her help in laboratory assays. Finally to the numerous patients, institutional Principal Investigators and Study Teams at each participating site.

Supported by NIH grants CA092461 (DFH), CA33601 (DAB) and CA25224 (JNI) from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and the Fashion Footwear Charitable Foundation of New York/QVC Presents Shoes on Sale ™(DFH).

The following institutions participated in this study: Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA–Harold J Burstein, M.D., Ph.D., supported by CA32291; Dartmouth Medical School - Norris Cotton Cancer Center, Lebanon, NH–Konstantin Dragnev, M.D., supported by CA04326; Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC–Jeffrey Crawford, M.D.,supported by CA47577; Long Island Jewish Medical Center, Lake Success, NY–Kanti R. Rai, M.D.,supported by CA35279; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA–Jeffrey W. Clark, M.D.,supported by CA32291; Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC–Mark Green, M.D.,supported by CA03927; Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY–Clifford A. Hudis, M.D., supported by CA77651; Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY–Lewis R.Silverman, M.D., supported by CA04457; North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System, New Hyde Park, NY–Daniel Budman, MD, supported by CA35279; Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI William Sikov, M.D., supported by CA08025; Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY–Ellis Levine, M.D., supported by CA59518; State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY–Stephen L. Graziano, M.D., supported by CA21060; University of Alabama, Birmingham, Birmingham, AL–Robert Diasio, M.D., supported by CA47545; University of California at San Diego, San Diego, CA–Barbara A. Parker, M.D., supported by CA11789; University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA–Charles J Ryan, M.D., supported by CA60138; University of Chicago, Chicago, IL–Hedy L Kindler, M.D., supported by CA41287; University of Illinois MBCCOP, Chicago, IL–David J Peace, M.D., supported by CA74811; University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA–Daniel A. Vaena, M.D., supported by CA47642; University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center, Baltimore, MD–Martin Edelman, M.D., supported by CA31983; University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA–William V. Walsh, M.D., supported by CA37135; University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN–Bruce A Peterson, M.D., supported by CA16450; University of Missouri/Ellis Fischel Cancer Center, Columbia, MO–Michael C Perry, M.D., supported by CA12046; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC–Thomas C. Shea, M.D., supported by CA47559; University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE–Anne Kessinger, M.D., supported by CA77298; University of Tennessee Memphis, Memphis, TN–Harvey B. Niell, M.D., supported by CA47555; University of Vermont, Burlington, VT–Steven M Grunberg, M.D., supported by CA77406; Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC–David D Hurd, M.D., supported by CA03927; Walter Reed Army Medical CALGB 9344p53 Lara et al 3 Center, Washington, DC–Brendan M Weiss, M.D., supported by CA26806; Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO–Nancy Bartlett, M.D., supported by CA77440; Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, NY–John Leonard, M.D., supported by CA07968

References

- 1.Rolland P, Spendlove I, Madjid Z, Rakha EA, Patel P, Ellis IO, et al. The p53 Positive Bcl-2 Negative Phenotype is an Independent Marker of Prognosis in Breast Cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1131–1137. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamashita H, Toyama T, Nishio M, Ando Y, Hamaguchi M, Zhang Z, et al. p53 Accumulation Predicts Resistance to Endocrine Therapy and Decreased Post-Relapse Survival in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(4):R48. doi: 10.1186/bcr1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lowe SW, Bodis S, McClatchey A, Remington L, Ruley HE, Fisher DE, et al. p53 Status and the Efficacy of Cancer Therapy in Vivo. Science. 1994;266:807–810. doi: 10.1126/science.7973635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakopoulou LL, Alexiadou A, Theodoropoulos GE, Lazaris AC, Tzonou A, Keramopoulous A, et al. Prognostic Significance of the Co-expression of p53 and C-erbB-2 Proteins in Breast Cancer. J Pathol. 1996;179:31–38. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199605)179:1<31::AID-PATH523>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersson J, Larsson L, Klaar S, Holmberg L, Nillson J, Inganass M, et al. Worse Survival for TP53 (p53)-Mutated Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Adjuvant Therapy. Ann of Oncol. 2005;16:743–748. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai MS, Sun XX, Lu H. Aberrant Expression of Nucleostemin Activates p53 and Induces Cell Cycle. Mol Cell Biol. 2008 Jul;28(13):4365–76. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01662-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamashita H, Nishio M, Toyama T, Sugiura H, Zhang Z, Kobayashi S, et al. Coexistence of Her-2 Over-expression and p53 Protein Accumulation is a Strong Prognostic Molecular Marker in Breast Cancer. Br Cancer Res. 2004;6:R24–R30. doi: 10.1186/bcr738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gülben K, Berberoğlu U, Cengiz A, Altinyollar H. Prognostic Factors Affecting Locoregional Recurrence in Patients with Stage IIIB Noninflammatory Breast Cancer. World J Surg. 2007;31:1724–1730. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiltschke C, Kindas-Muegge I, Steininger A, Reiner A, Preis PN. Coexpression of Her-2/neu and p53 is Associated with a Shorter Disease-free Survival in Node-positive Breast Cancer Patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1994;120:737–742. doi: 10.1007/BF01194273. 2004: 22; 86-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen PP, Lesser ML, Arroyo CD, Cranor M, Borgen P, Norton L, et al. p53 in Node-negative Breast Cancer: An Immunohistochemical Study of Epidemiologic Risk Factors, Histologic Features and Prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:821–830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.4.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elledge RM, Allred DC. The p53 Tumor Suppressor Gene in Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1994;32:39–47. doi: 10.1007/BF00666204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linjawi A, Kontogiannea M, Halwani F, Edwardes M, Meterissian S. Prognostic Significance of p53, Bcl-2, and Bax Expression in Early Breast Cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thor AD, Moore DH, Edgerton SM, Kawasaki ES, Reihsaus E, Lynch HT, et al. Accumulation of p53 Suppressor Gene Protein: An Independent Marker of Prognosis in Breast Cancer. J Nat Cancer Inst. 1992;84:845–855. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.11.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Overgaard J, Yilmaz M, Guldberg P, Hansen LL, Aisner J. TP53 is an Independent Prognostic Marker for Poor Outcome in Both Node-negative and Node-positive Breast Cancer. Acta Oncol. 2000;39:327–333. doi: 10.1080/028418600750013096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silvestrini R, Benini E, Veneroni S, Daidone MG, Tomasic G, Squicciarini P, et al. p53 and Bcl-2 Expression Correlates with Clinical Outcome in Series of Node-positive Breast Cancer Patients. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(5):1604–1610. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.5.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kröger N, Milde-Langosch K, Riethdorf S, Schmoor C, Schumacher M, Zander AR, et al. Prognostic and Predictive Effects of Immunohistochemical Factors in High-risk Primary Breast Cancer Patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(1):159–168. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silvestrini R, Veneroni S, Benini E, Daidone MG, Luisi A, Leutner M, et al. Expression of p53, Glutathione S-Transferas-π, and Bcl-2 proteins and Benefit from Adjuvant Radiotherapy in Breast Cancer. J Nat Cancer Inst. 1997;89(9):639–644. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.9.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malamou-Mitsi V, Gogas H, Dafni U, Bourli A, Fillipidis T, Sotiropoulou M, et al. Evaluation of the Prognostic and Predictive Value of p53 and Bcl-2 in Breast Cancer Patients Participating in a Randomized Study with Dose-Dense Sequential Adjuvant Therapy. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1504–1511. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thor AD, Berry DA, Budman DR, Muss HB, Kute T, Henderson IC, et al. ErbB-2, p53, and Efficacy of Adjuvant Therapy in Lymph Node-Positive Breast Cancer. J Nat Cancer Inst. 1998;90(18):1346–1360. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aas T, Borrensen AL, Geisler S, Smith-Sorensen B, Johnsen H, Varhaug JE, et al. Specific p53 Mutations are Associated with De Novo Resistance to Doxorubicin in Breast Cancer Patients. Nat Med. 1996;2(7):811–814. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kandioler-Eckersberger D, Ludwig C, Rudas M, Kappel S, Janschek E, Wenzel C, et al. TP53 Mutation and p53 Overexpression for Prediction of Response to Neoadjuvant Treatment in Breast Cancer Patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:50–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahko E, Blanco G, Soini Y, Bloigu R, Jukkola A. A Mutant TP53 Gene Status is Associated with a Poor Prognosis and Anthracycline-resistance in Breast Cancer Patients. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:447–453. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00499-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rozan S, Vincent-Salomon A, Zafrani B, Validire P, DeCremoux P, Bernoux A, et al. No Significant Predictive Value of C-ErbB-2 or p53 Expression Regarding Sensitivity to Primary chemotherapy or Radiotherapy in Breast Cancer. Int J Cancer. 1998;79:27–33. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980220)79:1<27::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris L, Fritsche H, Mennel R, Norton L, Ravdin P, Taube S, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 update of recommendation for the use of tumor markers in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(33):5287–312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henry L, Hayes DF. Uses and abuses of tumor markers in the diagnosis, monitoring and treatment of primary and metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist. 2006;11(6):541–52. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-6-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon RM, Paik S, Hayes DF. Use of archived specimens in evaluation of prognostic and predictive biomarkers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(21):1446–52. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Budman DR, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, Henderson IC, Wood WC, Weiss RB, et al. Dose and dose intensity as determinants of outcome in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. The Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(16):1205–11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.16.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henderson IC, Berry DA, Demetri GD, Cirrincione CT, Goldstein LJ, Martino S, et al. Improved outcomes from adding sequential Paclitaxel but not from escalating Doxorubicin in an adjuvant chemotherapy regimen for patients with node-positive primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(6):976–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayes DF, Thor AD, Dressler LG, Weaver D, Edgerton S, Cowan D, et al. Her-2 and Response to Paclitaxel in Node-Positive Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1496–1506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Minckwitz G, Sinn HP, Raab G, Loible S, Blohmer JU, Eidtmann H, et al. Clinical Response after Two Cycles Compared to Her-2, Ki-67, p53 and Bcl-2 in Independently Predicting a Pathological Complete Response after Preoperative Chemotherapy in Patients with Operable Carcinoma of the Breast. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R30. doi: 10.1186/bcr1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9067–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teusch SM, Bradley LA, Palomaki GE, Haddow JE, Piper M, Calonge N, et al. The Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Initiative: methods of the EGAPP Working Group. Genet Med. 2009;11(1):3–14. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318184137c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rahman- Robick R, Hellman U, Becker S, Bader FG, Auer G, Wiman KG, et al. Proteomic identification of p53-dependent protein phosphorylation. Oncogene. 2008;27(35):4854–9. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conway K, Edminston S, Cui L, Drouin SS, Pang J, He M, et al. Prevalence and Spectrum of p53 Mutations Associated with Smoking in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1987–1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasebe T, Iwasaki M, Akashi-Tanaka S, Hojo T, Shibata T, Sasajima Y, et al. p53 expression in tumor stromal fibroblasts forming and not forming fibrotic foci in invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:662–672. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]