Abstract

MicroRNAs regulate temporal transitions in gene expression associated with cell fate progression and differentiation throughout animal development. Genetic analysis of developmental timing in the nematode C. elegans identified two evolutionarily conserved microRNAs, lin-4/mir-125 and let-7, that regulate cell fate progression and differentiation and in C. elegans cell lineages. MicroRNAs perform analogous developmental timing functions in other animals, including mammals. By regulating cell fate choices and transitions between pluripotency and differentiation, microRNAs help to orchestrate developmental events throughout the developing animal, and to play tissue homeostasis roles important for disease, including cancer.

Introduction

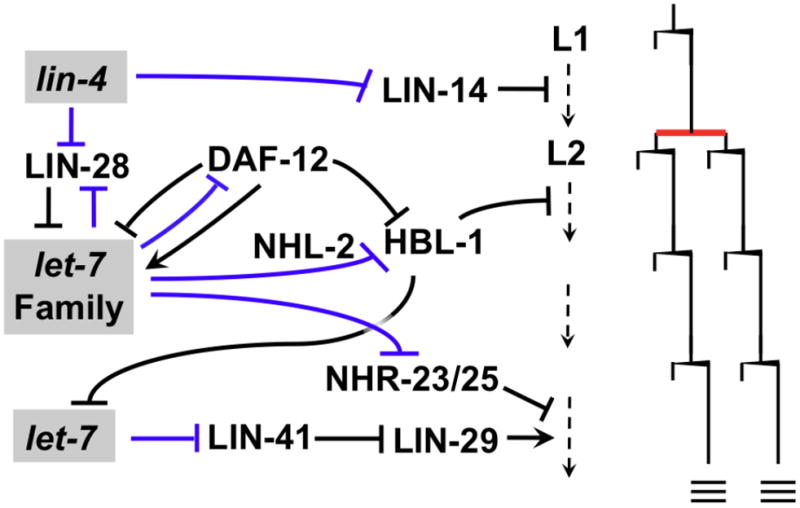

The roles for microRNA pathways in developmental timing were revealed by genetic analysis of worm mutants with particular kinds of defective larval cell lineages, in which events that re ordinarily restricted to specific stages of larval development occur at abnormal stages[1]. Cloning of the genes identified by these so-called heterochronic mutants of C. elegans led to the identification of the microRNA gene products of lin-4 [2] and let-7 [3]. lin-4 and let-7 regulate the timing of a wide variety of distinct developmental events in diverse cell lineages by progressively down regulating particular downstream targets (Figure 1), including the transcription factors LIN-14, HBL-1 and the TRIM protein LIN-41 [4]. MicroRNAs act post-transcriptionally on messenger RNA (mRNA) targets to which they base pair and repress production of the target protein. As post-transcriptional regulators with the ability to affect subtle changes in gene activity, or major microRNAs may be particularly suited for the regulation of the timing of events in diverse cell types and hence for coordinate the robust execution of temporal patterns of events throughout a developing organism.

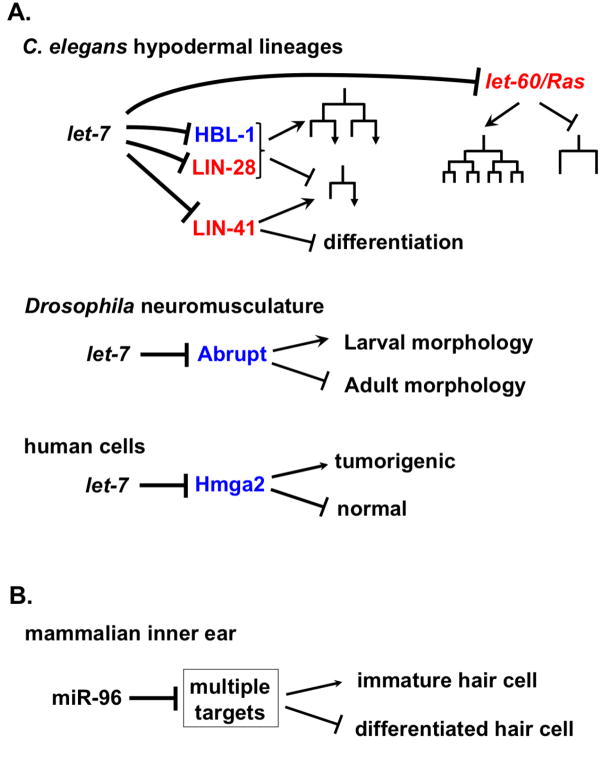

Figure 1. MicroRNAs and developmental timing in C. elegans.

MicroRNAs (shaded text boxes) of the lin-4 and let-7-Family control the temporal progression of cell fates in the lateral hypodermal “seam” cell lineages of developing C. elegans larvae. In each of stages L1-L4, seam cells undergo a single round of stem cell-like self-renewal divisions (wedge-shaped bars), with a single symmetric division (red bar) interposed in the L2 stage. At the L4 molt, seam cells exit the cell cycle and terminally differentiate (triple bars). MicroRNAs post-transcriptionally regulate key target mRNAs by direct interactions (blue lines) with to 3′ UTR sequences. Down regulation of the transcription factor LIN-14 by lin-4 microRNA is required for progression from the asymmetric L1 division pattern to symmetric division in the L2. Progression from the L2 to the L3 fate is caused by the down regulation of the transcription factor HBL-1 through the redundant activity of microRNAs of the let-7 family, which includes let-7, mir-48, mir-84, and mir-241 [15]. let-7-Family microRNA activity is modulated positively by the TRIM/NHL protein NHL-2 [24]. The L2 to L3 transition also involves down regulation of the RNA binding protein LIN-28 by lin-4 microRNA; LIN-28 acts upstream of the let-7-Family microRNAs [15]. The nuclear hormone receptor is the hub of a complex set of interactions that integrate microRNA and steroid hormone inputs to coordinate temporal cell fates with a decision to enter an optional diapause after the L2 stage [14]. Progression from a cycling status to terminally-differentiation at the L4 molt is conferred by a dramatic up-regulation of let-7 in the L4, resulting in down-regulation of the TRIM/NHL protein LIN-41, and consequent up regulation of the transcription factor LIN-29. HBL-1 represses let-7 transcription, ensuring that the up regulation of let-7 microRNA occurs only after completion of earlier steps. The cessation of molting after the L4 stage involves in part the down regulation, by let-7 family microRNAs, of the nuclear hormone receptor molting factors NHR-23 and NHR25 [17].

While lin-4 and let-7 each exerts its effects on cell fate progression in worm larvae by down regulating a major target (LIN-14 and LIN-41, respectively), a different sort of developmental progression is managed by miR430 in the fish embryo. miR430 expression rises rapidly to very high levels at about 4 hours of embryonic development, and targets hundreds of maternal mRNAs for deadenylation and destruction. Thus, in this case a microRNA triggers a major developmental transition by coordinating the elimination of mRNAs whose function is complete [5]

Interestingly, the involvement of microRNAs in developmental timing is reprised in plants in a fashion quite analogous to C. elegans (reviewed in [6]). Heterochronic mutants of corn exhibit global developmental timing defects reminiscent of those in worms [7]([8]. One of these corn mutants, Corngrass1 was found to result from over expression of the microRNA miR156 [9]. The miR156 microRNA, along with other microRNAs, also controls developmental transitions in Arabidopsis[10] [11]. Plant microRNAs are not related to animal microRNAs, and so these parallel roles for microRNA pathways in plant and animals represent independent evolutionary adaptations of microRNAs to developmental timing roles.

Here I will review recent advances in understanding the microRNA pathways controlling developmental timing in C. elegans, and how those studies are illuminating principles of animal microRNA function in general. Emphasis will be placed on relating the functions of worm lin-4 and let-7 microRNAs to the functions of their orthologous microRNAs in mammals (mir-125 and let-7, respectively). I will also discuss findings showing that in vertebrates, other microRNAs (unrelated to lin-4/mir-125 or let-7) function analogously to the C. elegans heterochronic microRNAs to control the temporal progression of cell fates within cell lineages, and transitions between pluripotency and differentiation.

Complex microRNA pathways control developmental timing in C. elegans

One overarching feature of the timing of developmental events in C. elegans lineages is the extreme robustness of the normal pattern, which is completely invariant among wild type worm. MicroRNAs play critical roles in posttranscriptional regulation of a set of key transcription factors, LIN-14, HBL-1 and LIN-29 that orchestrate coordinated stage-specific transcription programs throughout the developing larva. The lin-4-LIN-14 steps in the cascade occur cell-autonomously [12], so the coordination of events across the animal probably is not the consequence of extracellular traffic of microRNAs, but more likely involves a temporally coordinated activation of the microRNAs and/or communication by conventional hormones at later steps in the pathway [13], [14].

The temporal progression of cell fates in the lateral hypodermal cell lineages of the worm represents a simple model for stem cell lineages in general, which are characterized by regulated self-renewal and proliferative cell division patterns and the regulated production of differentiated cell types (Figure 1). A single proliferative division occurs in the C. elegans lateral hypodermal lineages, and is restricted to the L2 stage as a result of the stage-specific down regulation of the transcription factor HBL-1 (Figure 1). HBL-1 is high in the L1 and L2 stage, and then is down regulated in the L3. The down-regulation of HBL-1 is accomplished by semi-redundant activity of members of the let-7 family microRNAs (let-7-Fam), including mir-48, mir-84 and mir-241 [15]. Single-gene mutations of let-7-Fam microRNAs do not result in appreciable perturbation of the timing of lateral hypodermal events, but simultaneous mutation of two or more results repetition of the L2 proliferative division and delay of adult lateral hypodermal fates[15].

The complexity of the gene regulatory pathways in which let-7-Fam microRNAs function in C. elegans includes a feedback circuit involving let-7-Fam miRNAs and the DAF-12 transcription factor [14]. This circuit pathway involves both positive feedback and negative feedback between the microRNAs, whose transcription in regulated by DAF-12, and in turn DAF-12 is regulated by the let-7-Fam microRNAs. This circuit functions to integrate environmental signals and developmental timing, and to coordinate developmental quiescence with cell fate specification in the hypodermal lineages (Figure 1).

Another prominent role of let-7 in C. elegans is in terminal differentiation of the lateral hypodermal lineages in conjunction with the final larva-to-adult molt [3]. The terminal differentiation of these cells (termed the “larval-to-adult switch”) is mediated by up regulation of the let-7 microRNA in the L4 stage, which down regulates LIN-41 and thereby causes the up regulation of the LIN-29 transcription factor (Figure 1). The timing of let-7 up regulation is coupled to completion of previous larval development in part by a feed forward circuit wherein let-7 transcription is repressed by HBL-1 at earlier stages; full let-7 transcription in the L4 is permitted only after completion of the down regulation of HBL-1 by let-7 and her sisters during the L3 stage [16].

The larval-to-adult switch involves terminal differentiation of hypodermal cells, which is primarily triggered by let-7 via LIN-41 and LIN-29, and also the cessation of the cycle of molts (Figure 1). The conserved nuclear hormone receptors NHR-23 and NHR-25 control molting in the worm[17], and the cessation of larval molting results from the direct targeting of NHR-23 and NHR-25 by let-7-Fam microRNAs [18].

Integration of temporal information with other developmental signals

The heterochronic pathway microRNAs regulate, via their downstream target genes, a variety of distinct cellular behaviors. For example, lin-4 acts via its major target, LIN-14, to affect the timing of certain events in development of the worm nervous system -- in particular, in the timing of neural outgrowth in a neuronal type that matures postembryonically [19]. MicroRNAs also help coordinate differentiation and proliferation in other cell lineages, including cell cycle progression and cell fate commitment for vulval precursor cells (VPCs) [20]. Vulval development involves a precisely orchestrated temporal and spatial program of sequential signaling events involving an EGF organizer signal, transduced by the Ras pathway in the so-called 1° VPC, and a LIN-12/Notch lateral signal from the 1° VPC to its 2° VPC neighbors. The timing of Ras-mediated signaling in the 1° VPC is modulated by mir-84, a member of the let-7 family of microRNAs [21]. The Ras-activated fate of this cell includes sending a LIN-12/Notch lateral inhibitory signal to its neighbors, where the lin-4-LIN-14 circuit interfaces with the LIN-12/Notch gene expression program to help coordinate steps in cell cycle progression and 2° cell fate commitment [22]. LIN12/Notch activation in the 2° cells engages a feedback loop involving another (non-let-7- family) microRNA, mir-61. mir-61 down-regulates Ras signaling in the 2° VPC to help ensure mutual exclusivity of Ras and LIN-12/Notch signaling [23].

Modulation of the activities of temporal microRNAs

The distinctive developmental phenotypes associated with developmental timing microRNA pathways in C. elegans offers a powerful system for employing genetic screens to identify cofactors that regulate microRNA biogenesis or activity. RNAi screens for proteins that genetically interact with let-7-Fam microRNAs and modify their developmental timing phenotypes identified the conserved TRIM/NHL protein NHL-2, which functions as a positive co-factor for the activity of let-7-Fam microRNAs and other microRNAs [24]. The vertebrate and fly orthologs of NHL-2 have similar conserved microRNA-associated functions [25], suggesting that TRIM/NHL proteins could function widely to adjust the activity of let-7 and other microRNAs in the context of the physiology of the developing animal.

Another interesting cofactor for let-7 activity, also identified by genetic modifier screens in C. elegans, is the ribosomal protein RPS-14[26]. Reduction of RPS-14 by RNAi in the worm results in elevation of let-7 activity. The RPS-14 protein could be co-immunoprecipitated with the nematode miRISC Argonaute, ALG-1, suggesting a possible direct role for RPS-14 in miRISC activity. It is not know if the microRNA-associated activity of RPS-14 occurs in physical constituent of the ribosome, or in the context of a hypothetical extra-ribosomal function for RPS-14. Consistent with the theme of ribosome-miRISC functional interactions, another ribosome-associated protein, RACK1, has been found to genetically interact with microRNAs in C. elegans, and seems to physically associate with miRISC to promote microRNA activity in worms and mammalian cells [27].

RNAi screens for modulators of lin-4 control of developmental timing in C. elegans identified a conserved RNA binding protein gene rbm-28, which appears to affect the accumulation of lin-4 microRNA [28]. RMB-28 is homologous to the human RBM28, a nucleolar protein which has been implicated in diseases associated with defects in spliceosomal and/or ribosome biogenesis [29] [30] [31], suggesting a possible intersection of nucleolar RNP function and the regulation of lin-4 accumulation.

Conserved Functions of Developmental Timing MicroRNAs

The finding that let-7 microRNA is conserved in sequence and developmental expression across wide evolutionary distance [32] was a watershed discovery that set in motion searches for other small RNAs like let-7 and lin-4 (the only microRNAs known at the time). Rapidly thereafter, scores of microRNAs were identified in animals [33],[34], [35], and then plants [36]. An immediately apparent evolutionarily conserved characteristic of let-7 microRNA is its temporal up regulation in conjunction with advancing embryonic development and differentiation, and the absence of let-7 from pluripotent cells [32]. The evolutionary conservation of developmental timing roles for microRNAs, particularly the let-7 family of microRNAs, has been extensively reviewed [37], [38], [39], [40], [41]. Of particular note is the deep conservation of the direct negative feedback loop between let-7 and the pluripotency factor LIN-28 (Figure 2 A, Figure 3A). LIN-28 binds to pre-let-7 and inhibits production of the let-7 mature microRNA [42], which in turn directly represses LIN-28 production by base-pairing to the lin-28 mRNA, [43], [41]. Similarly, let-7 targeting of LIN-41 is conserved between nematodes and mammalian cells (Figure 2A), and the expression pattern of let-7 and mir-125/lin-4 microRNAs is inversely correlated with LIN-41 in mouse [44]. In C. elegans a let-7 family microRNA regulates Ras (LET-60) in the context of development of the vulval primordium (Figure 2A), and in mammals let-7 targets Kras in a range of cell types to inhibit proliferation [21]. These deeply conserved microRNA-target relationships seem to reflect core functions of the microRNA that are intimately engaged in fundamental regulatory circuitry of all animal cells.

Figure 2. Evolutionary conservation of developmental timing roles for microRNAs.

A. In nematodes, insects and mammals, let-7 family microRNAs control progression from earlier, or more proliferative states, to later, more differentiated states. These conserved activities in developmental progression can involve explicitly conserved targets (red), and non-conserved targets (blue). C. elegans let-7 family microRNAs act in several cell types to control early-to-late cell fate progression. Examples of targets that are conserved between C. elegans and mammals and insects include LIN-28, LET-60/Ras and LIN-41. Nonconserved targets of let-7 can nevertheless mediate roles for let-7 in promoting transitions from more primitive to more differentiated developmental states: examples include in Drosophila the down regulation of Abrupt in the control of a reorganization of the neuromusculature at metamorphosis [45],[46], and in humans the down regulation of the oncogene HMGA2 [67]. B. MicroRNAs of families other than let-7 can also control temporal developmental transitions, such as the case of miR-96, which is required for a program of differentiation in mammalian inner ear hair cells [53]. There could be multiple relevant targets of miR-96 in this context, since many mRNAs are deregulated in mir-96 mutant mice [51].

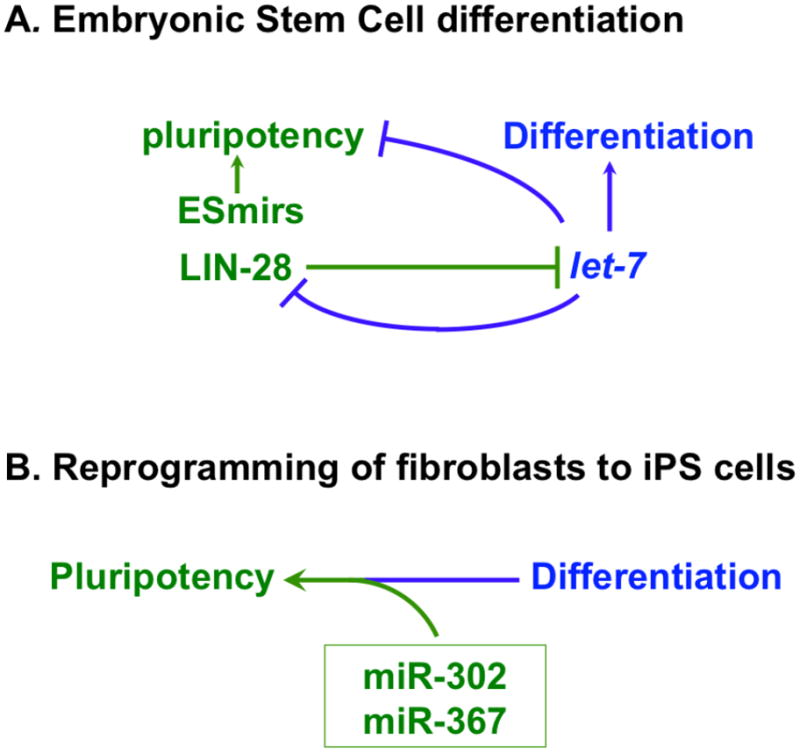

Figure 3. MicroRNAs and transitions between pluripotency and differentiation.

A. An evolutionarily conserved reciprocal repression between let-7 microRNA and LIN-28 results in mutually exclusive expression of LIN-28 between ES cells and differentiated cells, respectively. ES cell microRNAs (ESmirs) promote pluripotency and self-renewal together with other factors, including LIN-28, which acts in part by preventing expression of let-7. B. MicroRNAs miR-302 and miR-367 are expressed in stem cells of various types, including ES cells. Under certain conditions, experimental expression of miR-302 and miR-367 can be sufficient to reprogram mouse or human fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells [66].

A hallmark of the conservation of let-7 function as a differentiation factor and tumor suppressor is the fact that the target repertoire of let-7 displays remarkable evolutionary fluidity, while at the same time exhibiting a core set of conserved targets discussed above (LIN-28, Ras, LIN-41). Interestingly, the non- -conserved targets of let-7 are also set in the theme of temporal control of cell fate (Figure 2A). For example, in Drosophila, one of the temporal transitions regulated by let-7 is a reorganization of the neuromusculature of the fly during metamorphosis[45],[46]. A key let-7 target in this event is Abrupt[45], which is not a target of let-7 in worms or mammals. Similarly, a key target of let-7 in mammals is the oncogene HMG2A [47], orthologs of which are not targets of let-7 in worms or flies.

Similarly consistent with a conserved temporal control function, the mammalian lin-4 homolog miR-125b seems to regulate the proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells and also affects the balance of cell fates during lymphoid development, in part probably by acting as a lineage-specific anti-apoptotic factor [48]. miR-125b also plays analogous roles in the temporal progression of neuronal differentiation in humans by repressing multiple targets [49]. The apparent conserved roles for let-7 and miR-125/lin-4 microRNAs as a temporal regulators of cell fate transitions could reflect ancestral roles for these microRNAs.

Noteworthy advances around the subject of microRNAs in neural development include roles for the miR-183 family and for miR-96 in the development of sensorineural fates in the inner ear[50], [51], [52]. Particularly exciting is the finding that mutations in the miR-96 seed sequence are responsible for progressive hearing loss in certain human families[52]. Moreover, mice carrying miR-96 seed mutations exhibit a similar deafness [51], and the underlying developmental defect in these mice seems to be an arrest in the developmental progression program for inner and outer hair cells, as well as blocks in steps of auditory neural wiring [53]. Thus, mir-96 (which is not related in sequence to lin-4/miR-125 or let-7), controls a program of developmental progression for mammalian inner ear cells in a fashion analogous to the roles of C. elegans lin-4 and let-7 microRNAs in promoting developmental progression in worms cell lineages.

Developmental timing and Cancer

Consistent with an analogy between temporal progression of cell fates in C. elegans larval development, which is controlled by microRNA pathways, and cancer progression, lin-4/miR-125 and let-7 family microRNAs figure prominently in tumorigenesis (reviewed by [41]). Change in the level of miR-125 expression is a common characteristic of leukemia, and experimental support for a direct contribution miR-125 to leukemogenesis comes from mouse experiments. Over expression of miR-125 in transplanted mouse fetal liver results in elevated neutrophils and monocytes, and eventual B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or myeloproliferative disease[54]. These and other findings implicate miR-125b activity in specifying early stages of hematopoietic cell lineages. Targets for miR-125 in the context of hematopoesis and leukemia have not been identified, although miR-125 is predicted to target pro-apoptotic transcripts [55],[56], and p53 (at least in humans) {Le, 2009 #17150

Transitions between Pluripotency and differentiation

MicroRNAs participate in the regulated transitions of progenitor cells from a multipotent, self-renewal status towards differentiation in numerous cell lineages and tissues of vertebrate embryos. The roles of microRNAs in the development of mammalian skin [57] include the action of mir-203 to promote differentiation by repressing stemness [58].

A possible inverse relationship between microRNA expression and pluripotency of Embryonic Stem (ES) cells emerged from the finding that LIN-28 could act, together with three other proteins, to induce the reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotent stem cells {Yu, 2007 #6568}. LIN-28 inhibits expression of microRNAs associated with differentiation, including let-7 (Figure 2; Figure 3A). MicroRNAs that target LIN-28 (including miR-125/lin-4 and let-7)[59] are expressed during differentiation of cell lineages from ES cells in a fashion inversely correlated with LIN28 expression [60]. Certain microRNAs, such as miR-145 [59], or let-7 [61] can inhibit reprogramming of somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells.

However, recent findings provide evidence for a direct role for microRNAs in the pluripotency of Embryonic Stem (ES) cells. First, microRNA-depleted ES cells are incapable of producing differentiated cells, indicating that although they are viable, they do not possess the developmental potential characteristic of normal ES cells [62] [63]. Second, a distinct set of microRNAs are expressed in ES cells [64], and evidence indicates that these ES cell microRNAs (ESmirs, Figure 3) help maintain the pluripotency and self-renewal capacity of ES cells. Third, certain Myc-induced microRNAs can replace Myc in the generation of induced pluripotent cells [65], providing evidence for a potentially direct role for microRNAs in promoting pluripotency. Finally, expression of the miR302/miR367 microRNA locus from a viral vector has been shown to be sufficient to reprogram mouse or human fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells [66] (Figure 3B). The fact that reprogramming of somatic cells to induced pluripotency can be triggered by expression of just two microRNAs suggests that these microRNAs exert enormous leverage upon key gene regulatory network hubs that orchestrate bidirectional transitions between pluripotency and differentiation in mammals.

Conclusions

The C. elegans model system continues to be a valuable tool for discovering and characterizing microRNA pathway components involved in the organized developmental progression of cell lineages from earlier, more pluripotent stages, towards differentiation. Much work needs to be done, employing model organisms such as C. elegans, in conjunction with mouse and human genetics, to understand how microRNAs are temporally regulated in particular cell lineages, and how they engage specific targets in specific cell types in the context of developmental progression. Of particular interest in the near future are the apparently powerful roles of microRNAs in transitions between pluripotency and differentiation that are fundamental to developmental progression, tissue homeostasis, and human disease.

Highlights.

C. elegans heterochronic gene pathway is a model for temporal control of cell fates.

MicroRNAs have evolutionarily conserved functions in developmental timing.

MicroRNAs exert powerful roles in pluripotency and differentiation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ambros V, Horvitz HR. Heterochronic mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1984;226:409–416. doi: 10.1126/science.6494891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2•.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. This paper described the first known microRNA, the product of the lin-4 gene. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3•.Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;403:901–906. doi: 10.1038/35002607. This paper described the identification of the second known microRNA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slack FJ, Basson M, Liu Z, Ambros V, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G. The lin-41 RBCC gene acts in the C. elegans heterochronic pathway between the let-7 regulatory RNA and the LIN-29 transcription factor. Mol Cell. 2000;5:659–669. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schier AF, Giraldez AJ. MicroRNA function and mechanism: insights from zebra fish. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2006;71:195–203. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willmann MR, Mehalick AJ, Packer RL, Jenik PD. microRNAs regulate the timing of embryo maturation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1104/pp.110.171355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poethig RS. Heterochronic Mutations Affecting Shoot Development in Maize. Genetics. 1988;119:959–973. doi: 10.1093/genetics/119.4.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dudley M, Poethig RS. The effect of a heterochronic mutation, Teopod2, on the cell lineage of the maize shoot. Development. 1991;111:733–739. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.3.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuck G, Cigan AM, Saeteurn K, Hake S. The heterochronic maize mutant Corngrass1 results from over expression of a tandem microRNA. Nat Genet. 2007;39:544–549. doi: 10.1038/ng2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu G, Park MY, Conway SR, Wang JW, Weigel D, Poethig RS. The sequential action of miR156 and miR172 regulates developmental timing in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2009;138:750–759. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang L, Conway SR, Poethig RS. Vegetative phase change is mediated by a leaf-derived signal that represses the transcription of miR156. Development. 2010;138:245–249. doi: 10.1242/dev.058578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12•.Zhang H, Fire AZ. Cell autonomous specification of temporal identity by Caenorhabditis elegans microRNA lin-4. Dev Biol. 2010;344:603–610. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.018. This paper describes the first test of cell autonomy of a microRNA in C. elegans, and shows that lin-4 acts within the cells in which it is expressed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13•.Bethke A, Fielenbach N, Wang Z, Mangelsdorf DJ, Antebi A. Nuclear hormone receptor regulation of microRNAs controls developmental progression. Science. 2009;324:95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1164899. This paper describes the molecular mechanisms of action of a nuclear hormone receptor, DAF-12, in the integration of temporal and physiological signals in the developing worm larva. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14•.Hammell CM, Karp X, Ambros V. A feedback circuit involving let-7-family miRNAs and DAF-12 integrates environmental signals and developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18668–18673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908131106. This paper showed that the DAF-12 nuclear hormone receptor is engaged in reciprocal direct feedback regulation with let-7 family microRNAs whereby DAF-12 steroid ligand modulates both developmental progression and cell fate. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15•.Abbott AL, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Miska EA, Lau NC, Bartel DP, Horvitz HR, Ambros V. The let-7 MicroRNA family members mir-48, mir-84, and mir-241 function together to regulate developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Cell. 2005;9:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.07.009. This paper showed the semi-redundant roles of let-7 family microRNAs in the regulation of a single target, HBL-1. These findings established a model for redundant action of related microRNAs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roush SF, Slack FJ. Transcription of the C. elegans let-7 microRNA is temporally regulated by one of its targets, hbl-1. Dev Biol. 2009;334:523–534. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17•.Hayes GD, Frand AR, Ruvkun G. The mir-84 and let-7 paralogous microRNA genes of Caenorhabditis elegans direct the cessation of molting via the conserved nuclear hormone receptors NHR-23 and NHR-25. Development. 2006;133:4631–4641. doi: 10.1242/dev.02655. This paper showed for the first time a mechanism for how microRNAs can control the molting cycle in C. elegans. The findings expanded our perspective on the generality of microRNA-NHR pathways. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hada K, Asahina M, Hasegawa H, Kanaho Y, Slack FJ, Niwa R. The nuclear receptor gene nhr-25 plays multiple roles in the Caenorhabditis elegans heterochronic gene network to control the larva-to-adult transition. Dev Biol. 2010;344:1100–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olsson-Carter K, Slack FJ. A developmental timing switch promotes axon outgrowth independent of known guidance receptors. PLoS Genet. 2010:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Euling S, Ambros V. Heterochronic genes control cell cycle progress and developmental competence of C. elegans vulva precursor cells. Cell. 1996;84:667–676. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21•.Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, Cheng A, Labourier E, Reinert KL, Brown D, Slack FJ. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120:635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. This paper showed for the first time the evolutionarily conserved role of let-7 as a direct regulator of RAS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22•.Li J, Greenwald I. LIN-14 inhibition of LIN-12 contributes to precision and timing of C. elegans vulval fate patterning. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1875–1879. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.055. This paper demonstrated a role for the lin-4/lin-14 pathway in gating LIN-12/Notch signaling. These findings provide a model for how microRNA temporal signals can be integrated with growth factor positional signals. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoo AS, Greenwald I. LIN-12/Notch activation leads to microRNA-mediated down-regulation of Vav in C. elegans. Science. 2005;310:1330–1333. doi: 10.1126/science.1119481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammell CM, Lubin I, Boag PR, Blackwell TK, Ambros V. nhl-2 Modulates microRNA activity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell. 2009;136:926–938. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25••.Schwamborn JC, Berezikov E, Knoblich JA. The TRIM-NHL protein TRIM32 activates microRNAs and prevents self-renewal in mouse neural progenitors. Cell. 2009;136:913–925. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.024. The above two papers showed that the TRIM/NHL protein NHL-1 is an evolutionarily conserved positive modulator of microRNA activity. These findings provide a framework for investigating mode of post-transcriptional regulation of microRNAs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan SP, Slack FJ. Ribosomal protein RPS-14 modulates let-7 microRNA function in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 2009;334:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jannot G, Bajan S, Giguere NJ, Bouasker S, Banville IH, Piquet S, Hutvagner G, Simard MJ. The Ribosomal Protein RACK1 is required for miRNA function in both C. elegans and humans. EMBO J. 2011 doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.66. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bracht JR, Van Wynsberghe PM, Mondol V, Pasquinelli AE. Regulation of lin-4 miRNA expression, organismal growth and development by a conserved RNA binding protein in C. elegans. Dev Biol. 2010;348:210–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Damianov A, Kann M, Lane WS, Bindereif A. Human RBM28 protein is a specific nucleolar component of the spliceosomal snRNPs. Biol Chem. 2006;387:1455–1460. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nousbeck J, Spiegel R, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Indelman M, Shani-Adir A, Adir N, Lipkin E, Bercovici S, Geiger D, van Steensel MA, et al. Alopecia, neurological defects, and endocrinopathy syndrome caused by decreased expression of RBM28, a nucleolar protein associated with ribosome biogenesis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:1114–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spiegel R, Shalev SA, Adawi A, Sprecher E, Tenenbaum-Rakover Y. ANE syndrome caused by mutated RBM28 gene: a novel etiology of combined pituitary hormone deficiency. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162:1021–1025. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32••.Pasquinelli AE, Reinhart BJ, Slack F, Martindale MQ, Kuroda MI, Maller B, Hayward DC, Ball EE, Degnan B, Muller P, et al. Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory RNA. Nature. 2000;408:86–89. doi: 10.1038/35040556. This is a landmark paper that established that microRNAs are evolutionarily old and probably ubiquitous in most animals. The results instigated searches for microRNAs in addition to lin-4 and let-7, thereby triggering explosive growth of the microRNA field. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau NC, Lim LP, Weinstein EG, Bartel DP. An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294:858–862. doi: 10.1126/science.1065062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee RC, Ambros V. An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294:862–864. doi: 10.1126/science.1065329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35••.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science. 2001;294:853–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1064921. The above three papers showed for the first time that microRNAs are numerous and diverse in animals. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36••.Reinhart BJ, Weinstein EG, Rhoades MW, Bartel B, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs in plants. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1616–1626. doi: 10.1101/gad.1004402. This paper reported the first identification of microRNAs in plants. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pasquinelli AE, McCoy A, Jimenez E, Salo E, Ruvkun G, Martindale MQ, Baguna J. Expression of the 22 nucleotide let-7 heterochronic RNA throughout the Metazoa: a role in life history evolution? Evol Dev. 2003;5:372–378. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2003.03044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moss EG, Tang L. Conservation of the heterochronic regulator Lin-28, its developmental expression and microRNA complementary sites. Dev Biol. 2003;258:432–442. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frasch M. A matter of timing: microRNA-controlled temporal identities in worms and flies. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1572–1576. doi: 10.1101/gad.1690608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tennessen JM, Thummel CS. Developmental timing: let-7 function conserved through evolution. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R707–708. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41•.Nimmo RA, Slack FJ. An elegant miRror: microRNAs in stem cells, developmental timing and cancer. Chromosoma. 2009;118:405–418. doi: 10.1007/s00412-009-0210-z. The above five papers flesh out the concept of evolutionarily conserved roles for microRNAs in developmental timing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heo I, Joo C, Kim YK, Ha M, Yoon MJ, Cho J, Yeom KH, Han J, Kim VN. TUT4 in concert with Lin28 suppresses microRNA biogenesis through pre-microRNA uridylation. Cell. 2009;138:696–708. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43•.Rybak A, Fuchs H, Smirnova L, Brandt C, Pohl EE, Nitsch R, Wulczyn FG. A feedback loop comprising lin-28 and let-7 controls pre-let-7 maturation during neural stem-cell commitment. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:987–993. doi: 10.1038/ncb1759. This paper worked out the mechanism by which LIN-28 inhibits let-7 biogenesis, and established a molecular paradigm for a mode of microRNA regulation at the level of stability. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schulman BR, Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Reciprocal expression of lin-41 and the microRNAs let-7 and mir-125 during mouse embryogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:1046–1054. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sokol NS, Xu P, Jan YN, Ambros V. Drosophila let-7 microRNA is required for remodeling of the neuromusculature during metamorphosis. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1591–1596. doi: 10.1101/gad.1671708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46••.Caygill EE, Johnston LA. Temporal regulation of metamorphic processes in Drosophila by the let-7 and miR-125 heterochronic microRNAs. Curr Biol. 2008;18:943–950. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.020. The above two papers described the first genetic analysis of let-7 microRNA outside of C. elegans, and showed that in Drosophila the temporal control mode of action for let-7 is conserved. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee YS, Dutta A. The tumor suppressor microRNA let-7 represses the HMGA2 oncogene. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1025–1030. doi: 10.1101/gad.1540407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ooi AG, Sahoo D, Adorno M, Wang Y, Weissman IL, Park CY. MicroRNA-125b expands hematopoietic stem cells and enriches for the lymphoid-balanced and lymphoid-biased subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016218107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Le MT, Xie H, Zhou B, Chia PH, Rizk P, Um M, Udolph G, Yang H, Lim B, Lodish HF. MicroRNA-125b promotes neuronal differentiation in human cells by repressing multiple targets. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5290–5305. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01694-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li H, Kloosterman W, Fekete DM. MicroRNA-183 family members regulate sensorineural fates in the inner ear. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3254–3263. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4948-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mencia A, Modamio-Hoybjor S, Redshaw N, Morin M, Mayo-Merino F, Olavarrieta L, Aguirre LA, Del Castillo I, Steel KP, Dalmay T, et al. Mutations in the seed region of human miR-96 are responsible for nonsyndromic progressive hearing loss. Nat Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1038/ng.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lewis MA, Quint E, Glazier AM, Fuchs H, De Angelis MH, Langford C, van Dongen S, Abreu-Goodger C, Piipari M, Redshaw N, et al. An ENU-induced mutation of miR-96 associated with progressive hearing loss in mice. Nat Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1038/ng.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53••.Kuhn S, Johnson SL, Furness DN, Chen J, Ingham N, Hilton JM, Steffes G, Lewis MA, Zampini V, Hackney CM, et al. miR-96 regulates the progression of differentiation in mammalian cochlear inner and outer hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2355–2360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016646108. The above three papers report one of the first known examples of microRNA gene mutations in disease. In this case, the mutated microRNA gene is found to control a temporal progression in sensorineural cell differentiation in the inner ear. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bousquet M, Harris MH, Zhou B, Lodish HF. MicroRNA miR-125b causes leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016611107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xia HF, He TZ, Liu CM, Cui Y, Song PP, Jin XH, Ma X. MiR-125b expression affects the proliferation and apoptosis of human glioma cells by targeting Bmf. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2009;23:347–358. doi: 10.1159/000218181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao X, Tang Y, Qu B, Cui H, Wang S, Wang L, Luo X, Huang X, Li J, Chen S, et al. MicroRNA-125a contributes to elevated inflammatory chemokine RANTES levels via targeting KLF13 in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3425–3435. doi: 10.1002/art.27632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yi R, Fuchs E. MicroRNA-mediated control in the skin. Cell Death Differ. 2009;17:229–235. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yi R, Poy MN, Stoffel M, Fuchs E. A skin microRNA promotes differentiation by repressing ‘stemness’. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nature06642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu N, Papagiannakopoulos T, Pan G, Thomson JA, Kosik KS. MicroRNA-145 regulates OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 and represses pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2009;137:647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhong X, Li N, Liang S, Huang Q, Coukos G, Zhang L. Identification of microRNAs regulating reprogramming factor LIN28 in embryonic stem cells and cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41961–41971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.169607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Melton C, Blelloch R. MicroRNA Regulation of Embryonic Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Differentiation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 695:105–117. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7037-4_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leung AK, Young AG, Bhutkar A, Zheng GX, Bosson AD, Nielsen CB, Sharp PA. Genome-wide identification of Ago2 binding sites from mouse embryonic stem cells with and without mature microRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 18:237–244. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Melton C, Judson RL, Blelloch R. Opposing microRNA families regulate self-renewal in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2010;463:621–626. doi: 10.1038/nature08725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Houbaviy HB, Murray MF, Sharp PA. Embryonic stem cell-specific MicroRNAs. Dev Cell. 2003;5:351–358. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65•.Li Z, Yang CS, Nakashima K, Rana TM. Small RNA-mediated regulation of iPS cell generation. EMBO J. 2011;30:823–834. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.2. The above seven papers describe the microRNA expression profile in ES cells and present results associating the expression of those microRNAs with pluripotency. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66••.Anokye-Danso F, Trivedi CM, Juhr D, Gupta M, Cui Z, Tian Y, Zhang Y, Yang W, Gruber PJ, Epstein JA, et al. Highly Efficient miRNA-Mediated Reprogramming of Mouse and Human Somatic Cells to Pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.03.001. In Press. This paper provides the first evidence for a direct role of microRNAs in programming pluripotency in mammalian stem cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67•.Mayr C, Hemann MT, Bartel DP. Disrupting the pairing between let-7 and Hmga2 enhances oncogenic transformation. Science. 2007;315:1576–1579. doi: 10.1126/science.1137999. This paper showed that the Hmga2 oncogene is activated in human tumors by deletion of its 3′ UTR, and consequent release from repression by let-7. The paper showed a mechanism for let-7 tumor suppressive activity, and demonstrated the impact of 3′ UTR regulation in the context of human disease mechanisms. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]