Abstract

Researchers have long been interested in understanding the conditions under which evaluations will be more or less consistent or context-dependent. The current research explores this issue by asking when stability or flexibility in evaluative responding would be most useful. Integrating construal level theory with research suggesting that variability in the mental representation of an attitude object can produce fluctuations in evaluative responding, we propose a functional relationship between distance and evaluative flexibility. Because individuals construe psychologically proximal objects more concretely, evaluations of proximal objects will tend to incorporate unique information from the current social context, promoting context-specific responses. Conversely, because more distal objects are construed more abstractly, evaluations of distal objects will be less context-dependent. Consistent with this reasoning, the results of 4 studies suggest that when individuals mentally construe an attitude object concretely, either because it is psychologically close or because they have been led to adopt a concrete mindset, their evaluations flexibly incorporate the views of an incidental stranger. However, when individuals think about the same issue more abstractly, their evaluations are less susceptible to incidental social influence and instead reflect their previously reported ideological values. These findings suggest that there are ways of thinking that will tend to produce more or less variability in mental representation across contexts, which in turn shapes evaluative consistency. Connections to shared reality, conformity, and attitude function are discussed.

Keywords: attitudes, context-dependence, social influence, construal level, psychological distance

I wanted only to try to live in accord with the promptings which came from my true self. Why was that so very difficult? —Herman Hesse, Demian

Like the narrator in Herman Hesse's novel Demian, people often feel that they possess stable attitudes and beliefs about the world that derive from their “true selves”; yet they also find that these same attitudes and beliefs fail to guide them in many everyday social situations. At times, individuals act in accordance with their core values and ideals; at other times, their behavior seems to be shaped by the particularities of the current context. Indeed, questions about whether or when evaluative responses are more or less consistent or context-dependent have spurred theory and research across multiple domains, from the study of attitude–behavior correspondence to debates about the importance of ideology in guiding voter preferences (e.g., Converse, 1964; Fazio & Towles-Schwen, 1999; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1974; Jost, 2006).

In the present research, we explore this issue by considering when context-dependence or consistency would be more useful. Like other researchers, we assume that the primary function of attitudes is evaluative, in that they serve to provide a quick summary of whether an attitude object is positive or negative in order to facilitate approach or avoidance of that object (Eagly & Chaiken, 1998; Greenwald, 1989; Katz, 1960; M. B. Smith, Bruner, & White, 1956; Wilson, Lindsey, & Schooler, 2000). Furthermore, we propose that individuals must be able to regulate their behavior not only for the here and now but also with respect to objects outside the present situation. Building on past research, we suggest that cues about distance should therefore functionally shape evaluations to be more or less consistent or context-dependent. Whereas evaluations should flexibly incorporate information from the current context when individuals respond to proximal objects, they should help individuals transcend these immediate details when responding to distal objects.

Consistency and Context-Dependence in Evaluative Responding

Attitude Strength

Researchers have long been interested in elucidating factors that determine when evaluative responses will be more or less consistent or context-dependent. For example, the literature on attitude strength suggests that some attitudes tend to be relatively stable, whereas others tend to vary more, depending on the situation (e.g., Pomerantz, Chaiken, & Tordesillas, 1995; see Eagly & Chaiken, 1998; Krosnick & Petty, 1995, for reviews). Certain aspects of an attitude's structure seem to promote evaluative consistency across contexts, such as the correspondence between an overall evaluation and the evaluative meaning of supporting cognitions or affect, as well as an attitude's connectedness to other beliefs and values (see Chaiken, Pomerantz, & Giner-Sorolla, 1995, for a review). Research has also shown that strength-related variables such as attitude importance, clarity, and correctness predict increased evaluative consistency across time points or after receiving a counter-attitudinal message (e.g., Krosnick, 1988; Petrocelli, Tormala, & Rucker, 2007). Similarly, Fazio (2007; Fazio, Sanbonmatsu, Powell, & Kardes, 1986) has suggested that the strength of the association between an object and an evaluation critically influences the degree of evaluative consistency that an individual will display toward that object across contexts. From this perspective, because strong object–evaluation associations are activated automatically upon encountering an attitude object, strong associations should give rise to relatively consistent evaluative responses. In contrast, weak or as-yet unformed associations should produce context-dependent evaluations that are constructed in a more online fashion.

Objective Specification

Importantly, the consistency of evaluative responding across contexts depends not just on the intrinsic nature of an attitude (e.g., strong vs. weak) but also on the attitude object itself. Fishbein and Ajzen (1974, 1975) emphasized this crucial point in response to the flare of criticism in the 1960s over low attitude–behavior correlations (see e.g., DeFleur & Westie, 1958; McGuire, 1969; Wicker, 1969), helping to focus the field's attention on measurement issues that could be obscuring a stronger relationship between attitudes and behavior. According to Fishbein and Ajzen's compatibility principle, attitudes and behaviors can be more or less strongly correlated, depending on the extent to which an attitude object is specified during measurement (Ajzen, 1988). Inconsistencies in evaluative responding are therefore likely to arise when researchers specify attitude objects in mismatching ways—for example, when researchers attempt to use general attitudes (e.g., attitudes toward the environment) to predict specific behaviors (e.g., voting for a policy that would limit pollution). Thus, they suggested, researchers could increase the consistency of participants' evaluative responses from one measurement to another by specifying the attitude object in the same way at each time point.

Subjective Construal

Of particular relevance to the present research is the related idea that inconsistency in evaluative responding can stem from differences in the subjective representation of an attitude object, as well as differences in its objective specification (see also Ledgerwood & Trope, 2010). This notion dates back to Asch's (1940) distinction between “a change in the object of judgment, rather than in the judgment of the object” (p. 458)1 and has been echoed and elaborated on in more recent work on attitude flexibility (e.g., G. L. Cohen, 2003; Ferguson & Bargh, 2007; Lord & Lepper, 1999; Lord, Lepper, & Mackie, 1984; Schwarz, 2007). For example, attitude representation theory (Lord & Lepper, 1999) suggests that a person's evaluation of a given attitude object will depend on his or her subjective representation of that object; variability in subjective representation across contexts will therefore give rise to inconsistencies in evaluative responding. Thus, an individual's evaluation of the same social group (e.g., politicians) can shift, depending on which category exemplars are momentarily activated (e.g., a liked vs. disliked politician; Sia, Lord, Blessum, Ratcliff, & Lepper, 1997; see also Asch, 1940; Bodenhausen, Schwarz, Bless, & Waänke, 1995; Plant et al., 2009).

Likewise, Ferguson and Bargh (2007) proposed that attitudes might best be conceptualized as evaluations of “object-based contexts” (p. 232)—a phrase that emphasizes the notion that an individual's subjective representation of a given attitude object includes the context in which the object is encountered. In other words, variations in the context change the target of evaluation: A salty pretzel is a qualitatively different attitude object when one is hungry versus thirsty or when it is encountered resting on a plate versus resting on the ground (see also Asch, 1948). Together, these perspectives suggest that stability or change in the subjective mental representation of an attitude object can critically impact evaluative consistency.

Distance and Evaluative Responding

Promoting Effective Action

In the current research, we build on these perspectives to suggest that evaluative responses can indeed vary in their degree of consistency and that this variability in consistency may be highly useful. Certainly it seems plausible that context-dependent as well as context-independent evaluative responses could each promote effective action, depending on the situation. At times, context-specific evaluative responses that allow a person to flexibly adapt to the demands of his or her current social environment would be appropriate for guiding approach or avoidance of an attitude object (see e.g., Schwarz, 2007). After all, an object that should be approached in one context may need to be avoided in another: A person's reaction to a car slowly rolling closer should probably be different at midnight on a deserted street versus in daylight on a well-populated road. Moreover, flexible evaluative responses can facilitate the creation of socially shared viewpoints, which provide a necessary basis for interpersonal communication, social relationships, and coordinating dyadic and group behavior (see e.g., Brennan & Clark, 1996; Festinger, 1950; Hardin & Higgins, 1996; Turner, 1991). From this perspective, local evaluations that flexibly incorporate unique aspects of the current social situation might often be optimal for guiding action. Such a summary evaluation would presumably be shaped by details of the current context, including the presumed attitudes of another person who just happens to be in the present situation, as well as other social or nonsocial elements of the context, short-term concerns, and unique details of a particular instantiation of the attitude object.

On the other hand, local information can be irrelevant for evaluative responding. When a person is voting for the next state governor, for example, it does not seem particularly functional for variations in daylight or the slogan on a stranger's T-shirt to influence his or her decision about the candidates. Furthermore, consistent evaluative responses could help to protect and maintain already-established shared realities with important relationship partners or groups (see e.g., Asch, 1952; Hardin & Conley, 2001; Ledgerwood & Liviatan, in press; McGuire, 1969). From this perspective, global evaluative responses that summarize the extent to which an object is generally positive or negative could often be optimal for guiding action. This type of evaluative summary could provide a relatively context-independent guide for engaging with an attitude object by taking into account information from multiple situations. It would therefore be shaped by what is consistently relevant for action toward an attitude object across different situations, including broad principles and values, the views of long-term significant others or groups, normative societal standards, and central and enduring features of the attitude object.

Distance and Evaluative Consistency

When might context-dependence or consistency in evaluative responding be particularly useful? We suggest that in the present moment, individuals need to be able to act in line with their immediate goals, coordinate action with others around them, and interact effectively with their local environment. Local evaluations serve to guide approach/avoidance responding within the current situation, because they are sensitive to specific contextual information. However, as creatures who can also transcend the present situation to plan for future events, coordinate action at a distance, predict others' behaviors, and contemplate improbable occurrences, people must be able to regulate their behavior not only for the here and now but also for the there and then. Global evaluations thus serve to guide responding outside the present situation, by integrating evaluation-relevant information that is consistent across context.

Critically, then, the extent to which an attitude object is removed from the here and now should guide the extent to which evaluations incorporate context-specific versus context-independent information. Specifically, we suggest that variations in distance should shape the degree to which evaluations are relatively local, in that they reflect the current context, or relatively global, in that they reflect what is invariant across contexts. Furthermore, building on past research highlighting the importance of subjective representation in determining evaluative consistency (e.g., Asch, 1940; Ferguson & Bargh, 2007; Lord & Lepper, 1999), we propose that the manner in which an attitude object is subjectively construed could provide a key mechanism by which distance might lead evaluations to be more or less context-dependent.

Distance and Mental Representation

If, as discussed earlier, changes in the subjective representation of an attitude object produce changes in evaluative responding, then factors that influence the extent to which subjective mental representations fluctuate across contexts should have a critical impact on evaluative flexibility. Importantly, research has shown that psychological distance systematically impacts the extent to which an object is subjectively construed in terms of its abstract, essential, and superordinate characteristics (which tend to be context-independent) or in terms of its concrete, peripheral, and subordinate features (which tend to be context-specific; see Liberman & Trope, 2008; Trope & Liberman, in press, for reviews). Theory and research on the relation between distance and mental representation can therefore provide a critical mechanism for the link between distance and evaluative consistency proposed here.

Construal Level Theory

According to construal level theory, psychological distance plays a critical role in how we mentally construe the world around us (Liberman & Trope, 2008; Trope & Liberman, in press; Trope, Liberman, & Wakslak, 2007). The concept of psychological distance refers to any dimension along which an object or event can be removed from direct experience (i.e., me, here, and now), and thus dovetails nicely with the current perspective. Psychological distance is defined as perceived or experienced (rather than actual) distance and can include various dimensions such as time, space, and social distance.

Construal level theory suggests that people represent objects or events that are psychologically removed from them in terms of their high-level and abstract characteristics. Thus, as psychological distance increases, our mental representations tend to become more coherent and structured; they extract gist information and leave out irrelevant details. When the same objects or events are psychologically closer to us, we think about them in terms of low-level and detailed features. That is, with proximity, our mental representations become more concrete and lose the structure that separates important from peripheral and irrelevant features.

Research supports the notion that various dimensions of psychological distance similarly impact the level of construal. For instance, studies on temporal distance have shown that participants place greater weight on an object's or event's central features (e.g., the sound quality of a radio) versus peripheral features (e.g., the clarity of the radio's clock display) when making a decision for the distant future than when making a decision for the near future (Trope & Liberman, 2000, Study 3). Likewise, people tend to describe distant-future activities in terms of abstract ends and near-future activities in terms of concrete means (Liberman & Trope, 1998, Study 1; see also Vallacher & Wegner, 1985). Recent research suggests that other dimensions of psychological distance—including spatial distance, social distance, and hypotheticality—all increase the extent to which individuals mentally represent objects and events in a more abstract (vs. more concrete) manner (e.g., Fujita, Henderson, Eng, Trope, & Liberman, 2006; Libby & Eibach, 2002; Liviatan, Trope, & Liberman, 2008; Wakslak, Trope, Liberman, & Alony, 2006).

Level of Construal and Consistency

The impact of psychological distance on level of construal suggests a key mechanism by which distance could influence evaluative responding. By highlighting the central and defining features of an attitude object, abstract construals enable global evaluations that summarize what is consistent about the object across contexts. Thus, evaluations of distal attitude objects can be based on information relevant for evaluating the object's essential, core features and will appear relatively consistent in the face of contextual fluctuation. In contrast, by including the peripheral and contextual aspects of an attitude object, concrete construals enable local evaluations that summarize unique details of the present situation. Evaluative responses toward such objects can therefore incorporate evaluation-relevant information from specific contextual details and so will appear relatively flexible.

We therefore propose that distance shapes evaluative flexibility via its impact on the mental representation of an attitude object, which determines the basis or form of evaluation (i.e., a global vs. local summary of evaluative information). The key moderator of attitude flexibility is therefore not any one particular dimension of distance but rather any variable that influences the level at which an attitude object is mentally represented. Thus, we suspect that cues about distance— or more generally, any variable that leads people to adopt a more abstract mental representation of an attitude object—should tend to increase evaluative consistency, whereas cues about proximity— or concrete representations more generally—should tend to promote context-dependence.

The Current Research

The studies described here began to test the idea that psychological distance should shape evaluative flexibility by focusing on the critical issue of when people will be susceptible versus resistant to incidental social influences; that is, arbitrary aspects of the current social context that are not necessarily relevant for one's evaluative response. As guides to action (and interaction) in the current situation, local evaluative summaries should flexibly adapt to the immediate social context. Therefore, it was predicted that evaluations of psychologically proximal (vs. distal) attitude objects should show greater malleability in response to the incidental attitudes of a stranger (Studies 1 and 3). Furthermore, if distance influences attitude malleability via its impact on mental representation, then leading participants to think in a concrete or abstract manner should have a similar effect (Studies 2 and 4).

Although global (vs. local) evaluations should be less influenced by contextual factors, they should still relate to other attitude-relevant variables. Specifically, as guides to action (and interaction) that must transcend the present situation, global evaluations should reflect factors that relate to the central and enduring features of an attitude object. For example, ideological values can be considered broad principles that apply to attitude objects across situations, relate to their central and defining features, and tend to be socially shared within ongoing and important relational contexts (see e.g., Conover & Feldman, 1981; Jost, Ledgerwood, & Hardin, 2008; Kitt & Gleicher, 1950; Rokeach, 1968; Stillman, Guthrie, & Becker, 1960). Thus, although evaluations of psychologically distant or abstractly construed attitude objects (vs. near or concretely construed objects) should be less influenced by the immediate social context, they should be equally (or perhaps even more strongly) predicted by a person's ideological values (Studies 3 and 4).

These hypotheses were tested in a series of studies using an anticipated interaction paradigm adapted from previous research (Chen, Schechter, & Chaiken, 1996). Participants expected to discuss a social or political issue with an unknown interaction partner and learned that the partner either supported or opposed the issue before privately reporting their own attitudes. Study 1 focused on temporal distance and examined whether attitude alignment with the incidental discussion partner would be greater when a social policy was to be implemented in the near (vs. distant) future. It was hypothesized that participants' evaluations would incorporate their partner's attitude to a greater extent for the near-future versus distant-future policy. Studies 2a and 2b more directly examined the mechanism believed to underlie this effect by inducing participants to adopt a concrete, low-level focus or an abstract, high-level focus. We expected that participants primed to think concretely (vs. abstractly) would align their attitudes with those of their partner to a greater extent.

Studies 3 and 4 were designed to show that temporal distance and abstraction do not merely attenuate the relationship between evaluation and any potential predictor but instead differentially moderate this relationship, depending on whether the predictor is contextual or central to the attitude object. In these studies, participants' ideological values were measured at the beginning of the semester and were used to predict their subsequently reported evaluations in the anticipated interaction paradigm. It was hypothesized that temporal distance or a high-level construal manipulation would decrease the extent to which evaluations reflected an interaction partner's attitude (relative to temporally close or low-level construal conditions) but not the extent to which evaluations reflected people's previously reported ideological values.

Study 1: Temporal Distance and Social Alignment

Study 1 tested the basic notion that evaluative responses toward psychologically near objects would indeed show greater context-dependence than would evaluative responses toward psychologically distant objects. Participants took part in an anticipated interaction paradigm (Chen et al., 1996) in which they expected to discuss a proposed policy on assumed consent for organ donation with another student in the study. They learned that the policy was going to be implemented either next week (near-future condition) or next year (distant-future condition) and that their discussion partner was either in favor of or against assumed consent. Participants then privately reported their attitudes toward the described policy. On the basis of the theoretical perspective outlined earlier, it was hypothesized that participants would align their evaluative responses with those of their interaction partner to a greater extent when they were responding to a policy that was temporally close, compared with a policy that was temporally distant.

Method

Participants

Ninety-two New York University (NYU) undergraduate students (70 female, 22 male) in introductory and advanced psychology classes participated in partial fulfillment of a course requirement. They were randomly assigned to one cell of the 2 × 2 design and completed the study in groups of one to five. The experimenter was blind to condition.

Procedure and materials

Upon arrival in the lab, participants were greeted by the experimenter, who explained that the study was about “how people discuss their opinions on various issues” and then seated each participant individually in a computer cubicle. The remainder of the instructions appeared on the computer screen. Participants learned that they would be paired with another person who was participating in a separate session down the hall and would be assigned to discuss a randomly selected social or political issue with this other person. They expected that, after completing several background questionnaires, they would have a chance to meet their partner in person and then begin their discussion.

Temporal distance manipulation

Participants then saw a description of their discussion issue, which asked them to imagine that a policy had been proposed that would institute assumed consent for organ donation. In other words, consent for organ donation would become the default, and people could opt out if they wished not to donate. According to the description, this policy would start either “one week from today” (temporally near condition) or “one year from today” (temporally distant condition). Distance to the discussion partner, as well as time until the ostensible conversation, was held constant across conditions. Thus, the only difference between temporal distance conditions was whether the attitude object itself was close or distant in time.

Partner attitude

In order to manipulate the discussion partner's ostensible attitude in a subtle way, we interrupted participants when they were halfway through completing some background information about themselves to give them a message indicating that they had received some background information from their partner. They were then presented with demographic information (gender, age, year, major, and hometown), ostensibly provided by the discussion partner. At the bottom of the screen, in response to a general question from the researchers asking for comments, the partner appeared to have spontaneously typed: “i think this is a really important issue. i'm actually really in favor of [against] assumed consent for donating organs.” To maintain the cover story's credibility, we had participants then complete the rest of the background questions themselves.

Dependent variable

Next, participants completed a measure of their attitudes toward the proposed policy. The instructions informed participants that their responses to these items were solely for record-keeping purposes and would not be shared with their discussion partner. Participants were asked to rate their agreement with a series of seven statements (e.g., “I am in favor of the proposed policy, which would implement assumed consent for organ donation starting one week [one year] from today,” and reverse-coded: “Assuming consent for organ donation will create more problems than it will solve”) on a 9-point scale ranging from 1(Completely Disagree)to9(Completely Agree). Responses were averaged to form an index of attitudes toward the policy (α=.92).

Additional measures

Given that temporal distance could conceivably influence a number of variables besides just level of construal, participants were asked to respond to several additional items, including mood (“In general, how do you feel right now?”), interest (“How interesting do you think this issue is?”), and affiliation motivation. The latter construct was measured with four items used in previous research (e.g., “I think it is desirable to go along with the opinions of others when confronted with a controversial issue”; see DeWall, Visser, & Levitan, 2006), as well as two items designed specifically for the expected interaction context (“It is important to me to come to an agreement with my partner about the issue we are going to discuss” and “My goal for the upcoming discussion is to have a smooth and pleasant interaction”).2

After completing this last measure, participants were informed that no discussion would actually take place, were carefully probed for suspicion using a funnel technique, and were fully debriefed.

Results

Responses to the funnel debriefing revealed that six participants were highly skeptical of the scenario: They did not believe that the discussion partner existed and asserted that the experimental setup was fake. After confirming that these participants were equally distributed across conditions, they were excluded from the data set and analyses were conducted on the remaining 86 participants.

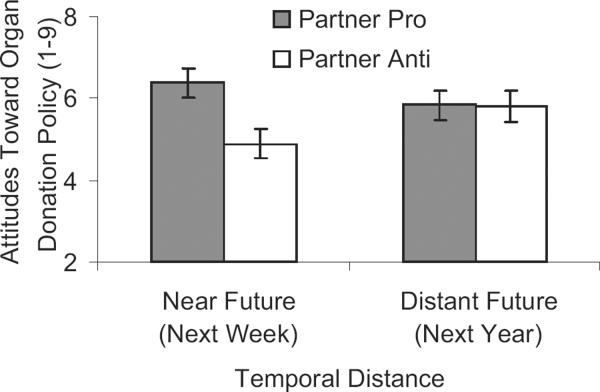

A 2 (temporal distance: near vs. distant) × 2 (partner attitude: pro vs. anti) between-subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted on participants' attitudes toward the proposed policy. There was a significant main effect of partner attitude, F(1, 82) = 4.22, p < .05, η2 = .05, such that overall, participants' attitudes toward the policy were more positive when the discussion partner was in favor of assumed consent for organ donation (M = 6.11) rather than against it (M = 5.35). There was no main effect of temporal distance condition (F < 1). More importantly, the predicted interaction between temporal distance and partner attitude emerged, F(1, 82) = 3.98, p < .05, η2 = .05. As expected, participants aligned their attitudes with those of their expected interaction partner when the policy was to be implemented next week, in the near future, F(1, 82) = 8.20, p < .01, η2 = .09. In contrast, their attitudes were unaffected by their partner's views when the policy was to be implemented next year, in the distant future (F < 1; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participants' attitudes toward a policy on assumed consent for organ donation as a function of temporal distance (i.e., when the policy would be implemented) and partner attitude (Study 1). Error bars indicate one standard error above and below the mean.

To confirm that these results were not due to an inadvertent effect of temporal distance on interest, mood, or affiliation motives, we conducted a series of independent sample t tests on the items included to measure these constructs. Temporal distance had no effect on interest or mood (ts < 1), nor was there any indication that distance increased affiliation motivation. In fact, one of the six items used to measure affiliation motivation actually showed a marginal trend in the opposite direction from what one would expect if temporal distance were somehow having an effect analogous to time perspective (see Footnote 1): Participants in the temporally distant (vs. near) condition agreed slightly more with the statement “There's nothing wrong with going along with what others say in order to get along with them,” t(84) = 1.65, p = .10. None of the other five items included to tap affiliative motives suggested any effect of distance (all ts < 1).

Discussion

In Study 1, participants' attitudes toward a policy on organ donation flexibly incorporated the position expressed by an incidental discussion partner when the policy was to be implemented in the near future (one week from today) but not the distant future (one year from today). Importantly, the manipulation of temporal distance was carefully designed in this study to vary only the time until the policy on assumed consent for organ donation would be implemented, while holding all other distances constant. Thus, participants in the two conditions expected to have the same amount of time until their encounter with their discussion partner and the same length of time during which to think about the policy before reporting their own attitudes (they were always asked to respond now, regardless of when the policy would be implemented). This ensured that participants in one temporal distance condition versus the other would not feel that their response was less consequential because they could change their decision later or would not feel more pressure to agree with their partner because the discussion was close.

Moreover, participants in the two temporal distance conditions reported similar levels of motivation to get along with their interaction partner, indicating that the distance manipulation was not simply changing the extent to which they were focused on agreeing or affiliating with other people. This is consistent with our suggestion that although local and global evaluations may be particularly useful for facilitating certain types of social coordination, they arise in response to cues about distance rather than only in response to explicit affiliative goals.3 Thus, our Study 1 findings provide intriguing initial support for the notion that responses to near attitude objects are guided by an evaluative summary that incorporates local information from the current social context, whereas responses to distant attitude objects are guided by a more global summary that is less context-dependent.

Study 2: Construal Level and Social Alignment

Our theoretical rationale suggests that Study 1's predicted pattern of results should not be an effect of time per se but rather a more general process that has to do with how an attitude object is mentally construed. In other words, the results of Study 1 presumably reflected a process in which increasing psychological distance leads participants to mentally represent an attitude object in terms of its central and defining features, which in turn enables global evaluative summaries of the attitude object that are less susceptible to incidental social influence.

Studies 2a and 2b zeroed in on this hypothesized mechanism by directly manipulating level of construal. Instead of seeking to indirectly influence construal level by changing an attitude object's temporal distance, these studies directly induced participants to adopt an abstract or concrete mindset using procedural priming techniques. Research has shown that when participants adopt such a mindset in one task, the primed cognitive procedures then transfer to other, seemingly unrelated tasks (Freitas, Gollwitzer, & Trope, 2004; Fujita, Trope, Liberman, & Levin-Sagi, 2006).

One way to procedurally prime abstract or concrete thinking is to focus participants either on the superordinate, goal-related aspects of activities or on more subordinate, concrete means. By asking people to generate more and more superordinate goals, one can lead them to think more abstractly in general. Conversely, by asking them to generate more and more subordinate means, one can lead them to think more concretely in general. In Study 2a, we adapted a mindset prime developed by Freitas et al. (2004) to induce participants to adopt either an abstract or a concrete mind-set. Previous research has shown that this task successfully manipulates level of construal (Freitas et al., 2004; Fujita, Trope, et al., 2006; P. K. Smith, Wigboldus, & Dijksterhuis, 2008).

Importantly, levels of construal differ not only in terms of their focus on ends versus means but also in the extent to which they emphasize broad categories versus specific exemplars. Consistent with this notion, past research has shown that abstract construals can be procedurally primed by asking participants to generate category labels, whereas concrete construals can be procedurally primed by asking participants to generate exemplars (Fujita & Han, 2009; Fujita, Trope, et al., 2006). Study 2b sought to provide a conceptual replication of Study 2a using this alternate manipulation of construal level. If our effects really reflect something about construal, then despite their superficial differences, these two manipulations should produce similar results.

After completing the mindset prime, participants in both studies learned that an anticipated interaction partner was either in favor of or against physician-assisted suicide. They then privately reported their attitudes toward this issue. We predicted that participants' own attitudes would be more influenced by an incidental stranger's attitudes when they had been led to think concretely, compared with when they had been led to think abstractly.

Method

Participants

Seventy-five NYU students (54 female, 21 male) participated in Study 2a, and 48 (22 female, 26 male) in Study 2b, for course credit. They were randomly assigned to one cell of the 2 × 2 design and completed the study in groups of one to five led by an experimenter blind to condition.

Procedure and materials

The procedure and materials were similar to those described in Study 1, except that Study 2a was conducted using pen-and-paper questionnaires and the following changes were made.

Construal level manipulation (Study 2a)

Participants in Study 2a were given a questionnaire described as a survey of student opinions and activities at the beginning of the study, while the experimenter ostensibly waited for a participant in the other session to arrive. This questionnaire manipulated level of construal by asking participants to generate either increasingly superordinate answers to the question of why they engaged in an activity (abstract condition) or increasingly subordinate answers to the question of how they engaged in the activity (concrete condition).

Participants in both conditions were presented with the activity “Do well in school.” In the abstract mindset condition, they were asked to start with the target activity and move up a ladder of four boxes, each connected with an upward-pointing arrow labeled Why? Thus, participants in this condition first answered the question of why they would do well in school and wrote their response in the next-highest box (e.g., “Get a good job”). Then they generated a reason why they would engage in each subsequent activity (e.g., one might get a good job in order to “Be successful”; one might be successful in order to “Have a happy life”). Participants in this condition therefore tended to finish the ladder by naming broad, abstract goals.

In the concrete mindset condition, participants were asked to start with the same activity of “Do well in school” but to move down a ladder of four boxes, each connected with a downward-pointing arrow labeled How? Participants in this condition therefore first answered the question of how they would do well in school and wrote this in the next-lowest box (e.g., “Study hard”). They continued to move down the ladder, generating increasingly subordinate means for how they would accomplish each subsequent activity (e.g., one could study hard by “Going to the library,” and one could get to the library by “Walking down the street”). Participants in this condition therefore tended to finish the ladder by naming concrete, specific means.4

Construal level manipulation (Study 2b)

Instead of answering the “Why/How” questionnaire, participants in Study 2b completed a word-generation task in which they were presented with a series of 40 words (e.g., soda, table, lunch, train, and soap opera). In the abstract mindset condition, participants were asked to generate a category to which each word belongs (e.g., a soda is an example of a beverage). In the concrete mindset condition, participants were instead asked to generate an exemplar for each word (e.g., an example of a soda is a Coke).

Partner attitude

After participants in both studies completed the construal level manipulation, the experimenter returned from ostensibly checking on the other session and explained that because the experiment was now running behind schedule, the discussion pairs would not have time to get acquainted in person before beginning their discussion (see Chen et al., 1996). Instead, they would exchange their background information sheets so that they could at least learn a bit about the other person. Participants received a background information sheet that appeared to have been completed by their discussion partner; it contained the same demographic information and manipulation of partner's attitude used in Study 1. In keeping with the cover story, participants also received a blank background information sheet to complete, which the Study 2a experimenter then took from the room as though delivering it to the participant's partner in the other session (in Study 2b, the computer program appeared to send the information over the Internet to the participant's partner).

Attitude object and dependent variable

To increase general-izability, Studies 2a and 2b involved a different attitude object from that used in Study 1. Moreover, to examine whether the pattern of results would replicate for general as well as specific attitudes, these studies focused on participants' attitudes toward an issue as a whole rather than only toward a particular policy as in Study 1. On the basis of pilot testing with a large sample of NYU students, we chose an issue toward which participants on average expressed attitudes near the midpoint of the scale, in order to avoid floor and ceiling effects. Participants in these studies therefore learned that their discussion issue was physician-assisted suicide. The dependent variable asked them to rate their agreement with seven items relating to this issue (e.g., “In general, how do you feel about physician-assisted suicide?” and “Should a terminally ill patient be able to choose to `pull the plug'?”) on 9-point scales ranging from 1 (e.g., Completely Oppose) to 9 (e.g., Completely Favor). Responses were averaged to form an index of attitudes toward physician-assisted suicide (α=.90 and α=.87 in Studies 2a and 2b, respectively).

Results

Study 2a

One participant was excluded for failing the manipulation check (misremembering the partner's position). Seven participants voiced suspicion about the existence of their interaction partner (e.g., two people noticed that the background information sheets all looked the same; several had previously participated in a similar study and knew that the setup was fake); analyses were conducted on the remaining 67 participants.5

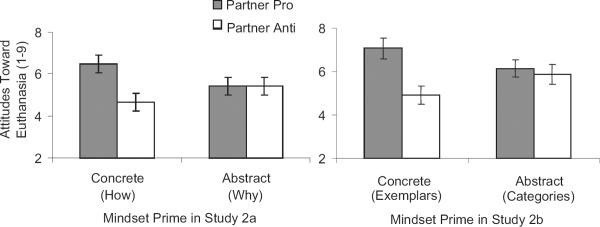

A 2 (construal level: abstract vs. concrete) × 2 (partner attitude: pro vs. anti) between-subjects ANOVA yielded a significant main effect of partner attitude, F(1, 63) = 4.53, p < .05, η2 = .07, indicating that overall, participants were more positive toward euthanasia when their partner was in favor of it (M = 5.95) rather than against it (M = 5.06). There was no main effect of construal level (F < 1). More importantly, the expected interaction emerged between construal level and partner attitude, F(1, 63) = 4.45, p < .05, η2 = .07. Consistent with our predictions, participants' attitudes depended on those of their partner when they had been led to adopt a concrete mindset, F(1, 63) = 8.84, p < .01, η2 = .12, but not after they had been led to adopt an abstract mindset (F < 1; see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Participants' attitudes toward euthanasia as a function of mindset prime condition and partner attitude (Studies 2a and 2b). Error bars indicate one standard error above and below the mean.

Study 2b

Four participants expressed suspicion about the existence of their interaction partner, and one was discovered engaged in a lengthy cell phone conversation in the midst of the study; analyses were conducted on the remaining 43 participants.

A 2 (construal level: abstract vs. concrete) × 2 (partner attitude: pro vs. anti) between-subjects ANOVA yielded a significant main effect of partner attitude, F(1, 39) = 7.76, p < .01, η2 = .17; again, participants expressed more positive attitudes toward euthanasia when their partner was in favor of it (M = 6.61) rather than against it (M = 5.39). There was no main effect of construal level (F < 1). Just as in Study 2a, the predicted interaction between construal level and partner attitude was significant, F(1, 39) = 4.69, p < .05, η2 = .11. Whereas participants' attitudes aligned with those of their partner after they had generated a series of concrete, specific exemplars, F(1, 39) = 11.50, p < .01, η2 = .23, attitudes were unaffected by the partner when participants had generated a series of abstract, general categories (F < 1; see Figure 2).

Discussion

In Study 2a, participants who completed a series of “How” questions designed to induce a concrete mindset subsequently aligned their attitudes toward euthanasia with the ostensible beliefs of an incidental interaction partner. When the partner was in favor of physician-assisted suicide, these participants were also in favor of it; when the partner was against it, participants were slightly against it. However, participants who completed a series of “Why” questions designed to induce an abstract mindset were unaffected by their partner's views.

In order to ensure that these effects were not due to some peculiar characteristic of the specific construal manipulation that we chose for Study 2a, Study 2b replicated our findings using an alternative manipulation. As expected, asking participants to generate a series of abstract categories or concrete exemplars produced the same pattern of results, lending additional confidence to our conclusions by triangulating on our construct of interest.

The results of Studies 2a and 2b provide initial evidence for the process hypothesized to underlie the effect of psychological distance on evaluative flexibility. Our perspective suggests that distance influences evaluation by changing the level at which an attitude object is mentally represented. Consistent with this notion, directly manipulating participants' level of construal produced results quite similar to those obtained in Study 1 with temporal distance.

Thus far, these studies support the notion that distance (or more generally, level of abstraction) can shape the extent to which evaluations fluctuate or remain stable in the face of changing contextual details. However, it is important to consider whether the lack of a social alignment effect in Study 1's distant-future or Study 2's abstract construal conditions necessarily reflects evaluative stability. It could be argued that this apparent stability resulted from apathy engendered by time discounting or the priming of superordinate goals (which could perhaps make certain political issues seem relatively unimportant). Notably, such an alternative account would suggest that nothing should predict individuals' attitudes when an attitude object is distant or after they are led to think abstractly, because in these cases, people simply do not care about the attitude object. The next two studies were designed to address this account.

Study 3: Temporal Distance and Ideological Values

We posit that, in contrast to the notion that psychological distance decreases susceptibility to incidental social influence simply because it increases apathy, distance leads people to focus on the central, enduring features of an attitude object while screening out irrelevant details and that this produces evaluative consistency in the face of changing contextual information. Thus, although incidental contextual factors should be less predictive of these global evaluations (compared with local evaluations), factors that relate to the central and enduring features of an attitude object should predict global (vs. local) evaluations equally well, if not better.

Consider the example of ideological values, relevant to the social and political attitudes measured here. Such values represent general principles that relate to the core features of attitude objects regardless of contextual variation and that tend to be consensually shared with long-term significant others and groups (e.g., Conover & Feldman, 1981; Jost et al., 2008; Rokeach, 1968; Stillman et al., 1960; see also Eagly & Chaiken, 1998). Thus, temporal distance should not decrease their tendency to predict evaluative responding. In fact, insofar as focusing on an object's central and defining features enables evaluations that relate more strongly to these features (rather than simply decreasing the extent to which evaluations relate to contextual features), evaluations of distal (vs. proximal) attitude objects could even be more likely to reflect people's ideological values (see also Eyal, Sagristano, Trope, Liberman, & Chaiken, 2009).

Study 3 was designed to test the hypothesis that temporal distance should decrease the extent to which a contextual factor but not a central factor predicts evaluation of an attitude object. Given the political nature of the issue to which participants would be responding, we assessed participants' ideological support for the societal status quo (one of two key components of left–right ideologies; see Jost, Banaji, & Nosek, 2004; Jost, Glaser, Kruglan-ski, & Sulloway, 2003) as a potential predictor of evaluation that should relate to the central features of a number of different political issues. The attitude object was a policy that would increasingly enforce the deportation of illegal immigrants. Insofar as incoming immigrants threaten to disrupt the status quo, the extent to which people value preserving the status quo should predict their evaluations of such a policy.6

Participants' ideological values were measured in a mass testing session at the beginning of the semester. Several weeks later, students participated in an ostensibly unrelated study, again involving an anticipated interaction paradigm. They read about a policy that would increase the deportation of illegal immigrants starting either next week (near future) or next year (distant future) and learned that their discussion partner was either in favor of or against deporting illegal immigrants. They then privately reported how likely they would be to vote in favor of the policy.

We expected that the relative influence of partner attitude and ideological values on voting intentions would differ depending on the temporal distance of the attitude object. Whereas increasing the temporal distance of the deportation policy should decrease the impact of another person's views on participants' own voting intentions (replicating the results of Studies 1 and 2 and extending them to expectations of behavior), it should not decrease the extent to which participants' previously reported ideological values predict their voting intentions.

Method

Participants

Thirty-eight NYU undergraduates (23 female, 14 male, and one unreported) participated in both the pretest and laboratory sessions for course credit. They were randomly assigned to one cell of the 2 (partner attitude) × 2 (temporal distance) experimental design and completed the study in groups of one to four. The experimenter was blind to condition.7

Procedure and materials

The procedure and materials were similar to those used in Study 1, except that they involved pen-and-paper questionnaires and included the following changes.

Pretest measure of ideological support for the status quo

As part of a mass testing session at the beginning of the semester, participants completed Kay and Jost's (2003) general system justification scale, which is designed to measure ideological support for the societal status quo. Participants rated their agreement with eight statements (e.g., “In general, the American political system operates as it should,” and reverse-coded: “American society needs to be radically restructured”) on a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree)to9(Strongly Agree). Responses were averaged for each participant (α = .86).

Attitude object and dependent variable

Participants were asked to “imagine that a policy has been proposed that would take steps toward deporting illegal immigrants, starting one week from today [one year from today]. In other words, next week [next year] deportation laws will become stricter and increasingly enforced.” After learning that their partner was in favor of or against deporting illegal immigrants, they completed the dependent measure, which asked them to “imagine that you're voting on the policy described, which will increase deportation starting one week [one year] from today. Do you vote in favor of the policy?” Participants responded on a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (Definitely Not)to9 (Definitely Yes).

Results

The central prediction for this study was that temporal distance would differentially moderate the effect of partner attitude and ideological values on voting intentions. In order to test this hypothesis, we conducted a planned contrast using a regression approach. First, participants' ideology scores were subjected to a median split (Mdn = 4.94) and interaction terms were computed for the two-way interactions between temporal distance and partner attitude (both dummy-coded) and between temporal distance and ideological values (also dummy-coded). Next, we conducted a linear regression with temporal distance, partner attitude, ideological values, and the 2 two-way interactions just noted as predictors and participants' voting intentions as the outcome variable.8

Support for the central prediction would be indicated if the moderating effect of temporal distance on partner attitude (i.e., the regression coefficient for the two-way interaction between temporal distance and partner attitude) differed from the moderating effect of temporal distance on ideological values (i.e., the regression coefficient for the second two-way interaction). A t statistic comparing these two coefficients can be computed as the difference between the coefficients divided by the pooled standard error. As expected, the two coefficients were significantly different, t(29) = 3.09, p < .05, suggesting that temporal distance did not have the same moderating influence for ideological values as it did for partner attitudes.9 Whereas distance (D) significantly decreased the impact of partner (P) attitude on voting intentions (BD × P = −3.66, SE = 1.51), t(32) = 2.42, p < .05, replicating our Study 1 results, it did not decrease the impact of ideological (I) values (continuous) on voting intentions (BD × I = 0.70, SE = 0.55), t(32) = 1.26, p = .22.

In order to explore these results more thoroughly, we conducted separate analyses regressing voting intentions on ideological values (continuous) and partner attitude for each temporal distance condition (see Table 1 for regression coefficients and effect sizes). Consistent with Studies 1 and 2, partner attitude significantly predicted voting intentions when the policy on illegal immigration was to be implemented next week (near-future condition), t(15) = 2.84, p < .05, but not when the policy was to be implemented next year (distant-future condition; t < 1). In contrast, ideological values significantly predicted voting intentions for the distant-future but not near-future policy, t(17) = 2.82, p < .05, and t < 1, respectively.

Table 1.

Linear Regression of Voting Intentions on Partner Attitude and Participants' Ideological Values Within Each Temporal Distance Condition (Study 3)

| Distance and variable | B | SE | β | Δ R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Near future | ||||

| Partner attitude | 3.39* | 1.20 | .59 | .34 |

| Ideological values | 0.12 | 0.49 | .05 | .00 |

| Distant future | ||||

| Partner attitude | −0.27 | 0.95 | −.06 | .00 |

| Ideological values | 0.81* | 0.29 | .56 | .32 |

Note. Participants' ideological values were measured at the beginning of the semester. ΔR2 = proportion of unique variance accounted for by the predictor (adjusting for the other).

p < .05.

Discussion

Study 3 extended the results of Studies 1 and 2 to a different attitude object (a policy on deporting illegal immigrants) and a different evaluative measure (participants' prediction of how they would vote on the policy, if they were voting on it now). Participants' voting intentions aligned with an interaction partner's attitude when the policy was set to be implemented in the near future but not when it was to be implemented in the distant future. However, temporal distance did not similarly dampen the relationship between ideological values and voting intentions, as a simple “distance leads to apathy” account would predict. If anything, voting intentions more strongly reflected participants' previously reported ideological values when the policy was to be implemented in the distant (vs. near) future. The more participants valued preserving the societal status quo at pretest, the greater their subsequent support for a distant-future policy that would enforce the deportation of illegal immigrants.

Thus, consistent with the perspective proposed here, evaluations of a temporally near attitude object flexibly incorporated the incidental attitudes of an interaction partner, whereas evaluations of a temporally distant object were not susceptible to incidental social influence yet still incorporated individuals' broad ideological values. Again, however, it was important to show that this pattern was not a unique effect of time but rather reflected a more general process by which mental representation influences the nature of evaluative responding. Study 4 therefore sought to replicate these results using a more direct manipulation of construal level.

In addition, it could be tempting to wonder about the surface resemblance between the temporal distance manipulation used in Studies 1 and 3 and classic manipulations of involvement that have been used in persuasion research, which are known to increase systematic or central route processing (e.g., Darke & Chaiken, 2005; Liberman & Chaiken, 1996; Petty & Cacioppo, 1984).10 After all, in conjunction with certain issues, time can be and has been used as a way to operationalize personal involvement or relevance. For example, researchers in one study manipulated personal relevance by asking NYU students to consider a new comprehensive exam requirement starting either next year or 10 years from now, so that “all [no] current students at New York University would be personally affected by this policy” (Liberman & Chaiken, 1996, p. 273). However, it is important to distinguish specific aspects of the manipulation used in such research from the underlying theoretical construct. In Liberman and Chaiken (1996), time was used in conjunction with a particular issue to help convince participants that the issue would have “significant consequences for their own lives” (Apsler & Sears, 1968, p. 162) and was therefore personally relevant: Manipulating the time until a comprehensive exam requirement begins is a straightforward way to change whether it will affect people (if it begins while they are at the university) or not (if it begins after they have left the university). There are of course other ways to manipulate relevance that do not involve time, such as varying whether a comprehensive exam requirement that begins now will only apply to new students or rather grandfather in all current students at a school (Liberman & Chaiken, 1996, Study 1). Likewise, there are ways to manipulate temporal distance that do not involve personal relevance. In fact, one could argue that most often, temporal distance does not affect whether an issue will have personal consequences for a person: A policy implemented at the national level that affects a particular individual will affect him or her regardless of whether it is implemented next week or next year, whereas a new requirement established at a foreign university will not affect that person, regardless of when it is implemented. Researchers who study personal involvement therefore often take considerable care when designing their studies in order to ensure that a particular manipulation in conjunction with a particular issue actually changes the extent to which participants feel as though an issue will affect them and therefore the extent to which they engage in systematic processing (e.g., Liberman & Chaiken, 1996; Petty & Cacioppo, 1984; Petty, Cacioppo, & Schumann, 1983).

In the present research, we varied temporal distance without using issues that would have personal consequences only if implemented in the near future. Thus, it seemed unlikely to us that our manipulation alone would influence the extent to which participants engaged in systematic processing, in the absence of additional information that could change whether people felt the issue would have significant personal consequences. Just to be sure, we confirmed this empirically: 86 NYU students completed a study in which they were asked about their thoughts and attitudes toward the issue of deporting illegal immigrants. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions. Two conditions replicated the temporal distance manipulation used here, suggesting that a deportation policy would be implemented either one week from today (near-future condition) or one year from today (distant-future condition). The other two conditions added additional information to the time manipulation in order to create conditions that would vary whether the issue carried significant consequences for the participants. In the high involvement condition, participants read that the deportation policy “would take steps toward deporting illegal immigrants, including a number of students or families of students at NYU, starting one week from today … which is likely to directly affect you and the people you know here at NYU.” In the low involvement condition, participants instead read that the policy “would take steps toward deporting illegal immigrants, including a number of students or families of students at the University of Texas, starting one year from today … although this is unlikely to directly affect you or anyone you know.” Participants then listed the thoughts that had occurred to them in the study so far (following standard thought-listing methodologies; e.g., Chaiken & Maheswaran, 1994; Chen et al., 1996), which provided two measures of extent of systematic processing: number of thoughts listed and time spent writing these thoughts.

Planned contrasts were conducted to test whether extent of systematic processing would differ between the two temporal distance conditions and between the high and low involvement conditions. Consistent with past research, participants in the high (vs. low) involvement condition listed more thoughts (M = 4.05 vs. 2.42) and spent more time elaborating (M = 2.55 min vs. 1.59 min), t(44) = 2.03, p < .05, and t(44) = 1.98, p = .05, respectively. In contrast, participants in the near-future versus distant-future condition listed similar numbers of thoughts (M = 3.10 vs. 3.30) and if anything spent a little less time elaborating (M = 1.68 min vs. 2.26 min; ps > .75 and .19, respectively). Thus, we feel confident in concluding that temporal distance, as manipulated in this research, is both theoretically and empirically distinct from prior manipulations of personal involvement.

Of course, one might still question whether the results of Studies 2a and 2b, which used more direct manipulations of construal level, could somehow be due to differences in systematic processing. For instance, perhaps thinking about broad, important goals in one's life decreases the perceived relevance of the task at hand. We therefore also included measures of systematic processing in Study 4, in order to explore whether procedurally priming people to adopt an abstract versus concrete mindset could be changing the extent to which they effortfully processed information. In a related vein, it seemed important to examine whether the variables of interest could do more than exert a potentially fleeting impact on scale judgments. Specifically, would these effects extend to people's self-generated cognitive elaborations about an attitude object, when they were asked to critically consider the issue?

Study 4: Construal Level and Ideological Values

Study 4 was designed to build upon the previous studies in three key ways. First, it included a measure of cognitive elaboration in order to address the questions just described. Second, it directly manipulated the process hypothesized to underlie the effects obtained in Study 3 by inducing participants to adopt a high-level (vs. low-level) mindset, in order to test whether this would produce similar results. Finally, it was designed to involve an issue toward which participants could express a definite attitude. Although Studies 1–3 examined attitude objects that are important and meaningful in the real world, they also deliberately involved issues for which on average, NYU student attitudes fell close to the neutral midpoint of an attitude scale, in order to avoid floor or ceiling effects that would hamper the detection of evaluative flexibility. However, it is possible that this neutral average reflected students' being somewhat unsure or ambivalent about these issues (so that they circled numbers close to the midpoint of the scale) rather than an approximately equal number of students supporting versus opposing the issue. In order to claim that the patterns observed in these studies are broadly descriptive of evaluative responding and not only applicable to attitude objects associated with unknown or ambivalent attitudes, it was important to show that the effects obtained thus far extended to objects toward which participants could express a valenced opinion. Thus, on the basis of pilot testing with a large sample of students, universal health care was chosen as an issue toward which most students reported a positive attitude.

The procedure for Study 4 largely followed that of Study 3. Students reported their ideological support for the status quo at the beginning of the semester and later participated in an ostensibly unrelated anticipated interaction paradigm. Level of construal was manipulated with the mindset prime used in Study 2a. Participants then learned that their discussion issue was universal health care and saw information about their partner's attitude on the issue. The main dependent variables were participants' own attitudes toward universal health care, as well as how likely they thought they would be to vote in favor of a policy to implement universal health care. In addition, using a measure of cognitive elaboration adapted from the persuasion literature (e.g., Cacioppo, Petty, Kao, & Rodriguez, 1986; Chaiken & Maheswaran, 1994; G. L. Cohen, 2003), we asked participants to list their thoughts about universal health care. These responses were used to create measures of both amount and positivity of systematic processing about the issue.

The central hypothesis was that construal level would differentially moderate the influence of ideological values and partner attitude on participants' attitudes toward the issue and toward a related policy. Specifically, participants led to adopt an abstract (vs. concrete) mindset should express attitudes toward universal health care that were less influenced by their partner's views but that were equally or more consistent with their previously reported ideological support for the status quo. Note that in this case, consistency between ideology and attitudes would suggest a negative relationship: The more people valued preserving the status quo, the more they should oppose radically changing the health-care system.11 It was expected that the positivity of participants' cognitive elaborations about the issue would follow a similar pattern.

Method

Participants

Seventy-two NYU students (51 female, 21 male) completed both pretest and laboratory sessions for course credit in the fall of 2007. They were randomly assigned to condition and completed the study in groups of one to four led by an experimenter blind to condition. Although participants were carefully seated facing away from each other to prevent them from seeing each other's materials, one person still noticed that the background sheets were all the same and was therefore excluded from the analyses.

Procedure and materials

The procedure and materials were similar to those used in Study 3, except where otherwise noted.

Pilot test of normative attitudes

In order to identify an issue toward which students could express clearly valenced attitudes, we conducted a pilot test in which we asked a large sample of students (N = 373) to indicate their positions on a number of different political and social issues (e.g., universal health care, legalizing marijuana) on a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (Completely Oppose) to9(Completely Favor). Participants also rated how personally important they felt each issue was on a 9-point scale ranging from 1(Not at all)to9(Extremely) and how certain they were about their attitude toward the issue on a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (Completely Uncertain)to9(Completely Certain).

On the basis of the results, we selected universal health care as the most appropriate attitude object, given the goals of the study. The majority of the sample (76%) circled a number above the midpoint of the 9-point attitude scale, indicating they supported the issue (M = 6.84, SD = 1.82). Participants were also moderately certain of their attitude (M = 5.98, SD = 1.89) and reported that the issue was moderately important to them personally (M = 5.46, SD = 1.96).

Pretest measure of ideological support for the status quo

As in Study 3, participants filled out Kay and Jost's (2003) measure of ideological support for the status quo at the beginning of the semester (α = .83).

Construal level manipulation

Instead of manipulating the temporal distance of the attitude object, we manipulated level of construal directly via the “Why/How” task from Study 2a, which induced participants to adopt an abstract or concrete mindset.

Attitude object and dependent variables

Participants learned that they would be discussing the issue of universal health care with another student who either supported or opposed it and then privately responded to the dependent measures. In the first measure, participants were asked: “Imagine that you're voting on a policy to implement a universal health-care program in this country. Do you vote in favor of the policy?” They responded on a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (Definitely Not)to9(Definitely Yes).

Attitudes toward the issue of universal health care as a whole were measured using five items (e.g., “In general, how do you feel about universal health care?” and reverse-coded, “Do you think that instituting a universal health-care program in the U.S. would create more problems than it would solve?”). Participants responded on 9-point scales ranging from 1 (Completely Oppose or Definitely Not)to9(Completely Favor or Definitely Yes); their responses were averaged to form an index of attitudes toward universal health care (α = .85).

In a second questionnaire, participants were asked to list up to five reasons why they thought health care was or was not a good idea. Amount of systematic processing could be operationalized as the number of thoughts listed or as the number of words written; both were computed to provide the best test of the possibility that amount of processing might differ by condition. In addition, two raters blind to condition independently coded each thought as positive, negative, or neutral/irrelevant (Cohen's κ = .93). Disagreements were resolved by a third rater. An elaboration positivity score was calculated for each participant by subtracting the number of negative thoughts from the number of positive thoughts (see e.g., Chaiken & Maheswaran, 1994; G. L. Cohen, 2003; Pomerantz et al., 1995).

Additional measures

To check for possible effects of construal level on involvement-related variables, we also asked participants to indicate how important, interesting, and personally relevant the discussion issue was to them, as well as the extent to which they thought the issue required careful thought and consideration. To check for possible effects on more affective or motivational variables, we asked them to indicate their overall mood, how important they felt it was to get along and agree with their partner, and how positively they felt toward their partner. To confirm that construal level was not changing the extent to which participants believed their partner's attitude to be incidental versus representative of others' opinions, we asked two additional items concerning how similar participants thought their partner's view was to other NYU students' views and to other people's views in general.

Results

As in Study 3, the central hypotheses could be most directly tested by conducting planned contrasts of regression coefficients. To do so, we first dichotomized the premeasure of ideological values using a median split (Mdn = 4.13) and computed terms for the two-way interactions between construal level and partner attitude (dummy-coded) and between construal level and ideological values (dummy-coded). In a series of analyses, we regressed each dependent variable (see next sections) on construal level, partner attitude, ideological values (dichotomized), and the 2 two-way interactions of interest and then compared the regression coefficients for the two interactions to determine whether the relative impact of partner attitude and ideological values differed, depending on level of construal.12

Voting intentions

We first examined voting intentions as the dependent variable. The planned contrast comparing the two interaction coefficients was significant, t(65) = 2.51, p < .05, indicating that the moderating impact of construal (C) level on partner attitude versus ideological values was significantly different. Whereas inducing an abstract mindset significantly decreased the impact of partner attitude on voting intentions (BC × P = −2.90, SE = 0.98), t(65) = 2.95, p < .01, it did not decrease the impact of ideological values (continuous; BC × I = 0.27, SE = 0.36, t < 1). To further explore these results, we regressed the voting intention item on partner attitude and ideological values (continuous and centered) separately for each construal level condition. The pattern mirrored that obtained in Study 3 (see Table 2 for all regression coefficients and effect sizes). After participants had been led to think concretely, they reported that they were more likely to vote for the policy when their partner supported (vs. opposed) universal health care, t(35) = 3.53, p < .01, but their voting intentions were not significantly predicted by previously reported ideological values (p > .25). In contrast, after participants had been led to think abstractly, their ideological values significantly predicted their voting intentions such that greater support for the status quo led participants to report they were less likely to vote to change the health-care system, t(30) = 2.52, p < .05, whereas partner attitude had no effect (p > .65).

Table 2.

Linear Regression of Voting Intentions on Partner Attitude and Participants' Ideological Values Within Each Construal Level Condition (Study 4)

| Construal level and variable | B | SE | β | Δ R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concrete (low level) | ||||

| Partner attitude | 2.63* | 0.75 | .50 | .25 |

| Ideological values | −0.31 | 0.27 | −.16 | .03 |

| Abstract (high level) | ||||

| Partner attitude | −0.27 | 0.62 | −.07 | .01 |

| Ideological values | −0.58* | 0.23 | −.42 | .17 |

Note. Participants' ideological values were measured at the beginning of the semester. ΔR2 = proportion of unique variance accounted for by the predictor (adjusting for the other).

p < .05.

Attitudes toward universal health care

A similar planned contrast, now with attitudes toward universal health care as the dependent variable, again yielded a significant difference between the 2 two-way interaction coefficients, t(64) = 2.45, p < .05.13 Whereas abstract construals significantly decreased the impact of partner attitude on own attitudes (BC × P = −1.53, SE = 0.72), t(64) = 2.13, p < .05, they did not decrease the impact of ideological values (continuous; BC × I = 0.26, SE = 0.26, t < 1). Follow-up analyses regressing attitudes toward universal health care on partner attitude and ideological values (centered) separately for each construal level condition yielded the expected pattern. Mirroring the results for voting intentions, participants in the concrete construal condition reported attitudes that reflected partner attitudes but not previously reported ideological values, t(35) = 2.97, p < .01, and t < 1, respectively, whereas participants in the abstract construal condition reported attitudes that reflected ideological values but not partner attitudes, t(29) = 2.44, p < .05, and t < 1, respectively (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Linear Regression of Participants' Attitudes on Partner Attitude and Participants' Ideological Values Within Each Construal Level Condition (Study 4)

| Construal level and variable | B | SE | β | Δ R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concrete (low level) | ||||

| Partner attitude | 1.55** | 0.52 | .44 | .19 |

| Ideological values | −0.17 | 0.19 | −.14 | .02 |

| Abstract (high level) | ||||

| Partner attitude | 0.02 | 0.48 | .01 | .00 |

| Ideological values | −0.43* | 0.18 | −.41 | .17 |

Note. Participants' ideological values were measured at the beginning of the semester. ΔR2 = proportion of unique variance accounted for by the predictor (adjusting for the other).

p < .05.

p < .01.

Elaboration positivity

A planned contrast for the two interaction terms when elaboration positivity was entered as the dependent variable was also significant, t(65) = 2.44, p < .05. Abstract construals significantly reduced the impact of partner attitude on elaboration positivity (BC × P = −3.09, SE = 1.32), t(65) = 2.35, p < .05, but did not reduce the impact of ideological values (continuous; BC × I = 0.33, SE = 0.48, t < 1). Follow-up analyses regressing elaboration positivity on partner attitude and ideological values (centered) separately for each construal level condition revealed the predicted pattern (see Table 4). When participants had been led to think concretely, partner attitude drove the positivity of their elaborations, t(35) = 2.14, p < .05. To shed additional light on this effect, we calculated predicted values using the regression equation for the low-level construal condition. Overall, participants tended to generate more positive than negative elaborations about universal health care, consistent with the normative positive attitude toward this issue in our student population. However, on average, this tendency was greater when the partner favored (vs. opposed) universal health care. When the partner supported the issue, the predicted elaboration positivity score was 2.74, indicating that on average, participants spontaneously generated almost three more positive than negative thoughts about the issue. When the partner opposed the issue, the predicted positivity score was only 0.64, indicating that on average, the numbers of positive and negative thoughts were close to equal.

Table 4.