Abstract

Since the discovery of Tumor Necrosis Factor-Related Apoptosis Inducing Ligand (TRAIL) in 1995, much has been learned about the protein, its receptors and signaling cascade to induce apoptosis and the regulation of its expression. However, the physiologic role or roles that TRAIL may play in vivo are still being explored. The expression of TRAIL on effector T cells and the ability of TRAIL to induce apoptosis in virally infected cells provided early clues that TRAIL may play an active role in the immune defense against viral infections. However, increasing evidence is emerging that TRAIL may have a dual function in the immune system, both as a means to kill virally infected cells and in the regulation of cytokine production. TRAIL has been implicated in the immune response to viral infections (good), and in the pathogenesis of multiple viral infections (bad). Furthermore, several viruses have evolved mechanisms to manipulate TRAIL signaling to increase viral replication (ugly). It is likely that whether TRAIL ultimately has a proviral or antiviral effect will be dependent on the specific virus and the overall cytokine milieu of the host. Knowledge of the factors that determine whether TRAIL is proviral or antiviral is important because the TRAIL system may become a target for development of novel antiviral therapies.

Keywords: Apoptosis, cell mediated immunity, human immunodeficieny virus, hepatitis, hepatitis C virus, hepatitis B virus, cytomegalovirus, epstein-barr virus, tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand

INTRODUCTION AND DISCOVERY OF TRAIL

In 1995 [1] and 1996 [2], two independent groups described a novel member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily, designated tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and Apo-2L, respectively. Both groups screened human cDNA for sequence homology with TNF and Fas ligand. A gene containing 1769 base pairs with an open reading frame encoding a 281 amino acid protein was found. Structural prediction of the gene product revealed a type II transmembrane protein with a C-terminal extracellular region, an internal hydrophilic domain, and a calculated molecular mass of 32.5 kDa. Northern blot analysis revealed TRAIL/Apo2L mRNA expression in a wide variety of human tissues, including fetal lung, liver, thymus, ovary, small and large intestines, peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs), heart, placenta, skeletal muscle and kidney. Initial experiments demonstrated that, like TNFα and FasL, TRAIL/Apo2L induced apoptosis in some transformed cell lines but not others. Importantly, unlike TNFα and FasL, TRAIL did not induce apoptosis in normal cells. Subsequent studies have shown that other non-apoptotic effects of TRAIL can occur in healthy cells [3]. TRAIL also has the potential to induce non-apoptotic programmed cell death (via autophagy, necrosis, etc.) if the apoptotic machinery is inhibited [4].

In the short time since its initial description, a great deal has been learned about the structure of TRAIL, its five known receptors, its complex signaling cascade and regulation, and its biological activity. TRAIL induced apoptosis has been found to contribute to multiple disease processes and protect against others, and early clinical trials are underway to exploit this latter phenomenon [5]. It is the purpose of this review to explore the role of TRAIL in the pathogenesis and host immune response to viral infections.

TRAIL GENE AND PROTEIN STRUCTURE

The gene for TRAIL is located on chromosome 3 and consists of five exons with a 1.2 kbp upstream promoter region [5, 6]. The protein product contains a short intracytoplasmic domain, a transmembrane region and a large extracellular domain [6]. The extracellular domain contains two antiparallel beta pleated sheets that form a beta sandwich as well as a 12 to 16 amino acid N-terminal insertion loop [7]. TRAIL monomers interact to form a homotrimer which can interact with TRAIL receptors via the three identical clefts formed between neighboring subunits [8]. The cysteine-230 residue in the receptor binding domain is critical for the stability of the homotrimer, receptor binding [9] and apoptotic activity [10]. Two splice variants of the TRAIL message have been described [6]. The biologic significance of the TRAIL splice variants is not known, but their presence is not surprising given an estimated 35–59% of human genes undergo alternative splicing, and most of these genes are involved in signaling and regulation pathways [11].

REGULATION OF TRAIL EXPRESSION AND LINKS TO THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

As noted above, TRAIL is expressed by a wide variety of human tissues, and is notably expressed on multiple cell types within the immune system. Immune cells that express TRAIL include both activated and resting B lymphocytes [12], as well as activated T lymphocytes [12], natural killer (NK) cells [13], monocyte/macrophages [14] and dendritic cells [15]. The regulation of TRAIL expression in immune system cells is cytokine driven. Interferon alpha (IFNα) and interferon gamma (IFNγ) stimulate TRAIL expression in monocytes [14] and dendritic cells [15]. IFNα and interferon beta (IFNβ) stimulate TRAIL expression in T lymphocytes [16] and NK cells [17]. Interleukins 2, 7 and 15 can also induce NK cell expression of TRAIL [16]. Interestingly, bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulates TRAIL expression in monocytes and macrophages and augments their cytotoxicity [18].

The expression of TRAIL on immune cells and the stimulation of TRAIL expression by proinflammatory cytokines and LPS supports the hypothesis that TRAIL is a participant in the immune system. Because Type 1 interferons stimulate TRAIL expression and are known to coordinate the immune response to intracellular pathogens by multifactorially creating an ‘antiviral state’ [19], it would seem safe to assume that TRAIL would be an active participant in the immune response to viral infections. What is not clear and will be discussed further is whether TRAIL serves as an effecter or a regulator of the immune system in response to viral infections.

TRAIL Receptors and Signaling

Receptors

In order to understand the effect of TRAIL on viral infections, and vice versa, we must first review the basics of the TRAIL receptors and signaling cascades. There are five known receptors for TRAIL. TRAIL receptor 1 (TRAIL-R1, or death receptor 4, DR4) is a 468 amino acid transmembrane protein with a 70 amino acid intracellular death domain [20]. TRAIL-R2, or DR5, is a 411 amino acid protein 58% homologous to TRAIL-R1 and also contains an intracellular death domain [21, 22]. Both TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 are expressed in a wide variety of normal and transformed tissues and cell lines, but not all tissues and cells that express these receptors are TRAIL sensitive. TRAIL-R3 is a 299 amino acid protein that lacks the intracellular death domain and therefore does not induce apoptosis when bound by TRAIL – it has also been referred to as Decoy Receptor 1 (DcR1), Lymphocyte Inhibitor of TRAIL (LIT) and TRID [21, 23–25]. TRAIL-R4, or Decoy Receptor 2 (DcR2), or TRAIL receptor with a truncated death domain (TRUNDD), is aptly described – a 386 amino acid protein with a truncated and inactive intracellular death domain when bound to TRAIL [26–28]. The final receptor for TRAIL is a soluble decoy receptor – osteoprotegerin (OPG) [29, 30]. Osteoprotegerin is a secreted TNF receptor homologue that both inhibits osteoclastogenesis and increases bone density, as well as binds TRAIL and is capable of inhibiting in vitro TRAIL mediated apoptosis. The role of osteoprotegerin in TRAIL regulation in vivo is not known.

At body temperature, TRAIL’s affinity is greatest for TRAIL-R2, then TRAIL-R1, the decoy receptors and lastly osteoprotegerin [31]. Both TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 propagate pro-apoptotic signals when they interact with either soluble or membrane bound TRAIL [32, 33].

Signaling Cell Death

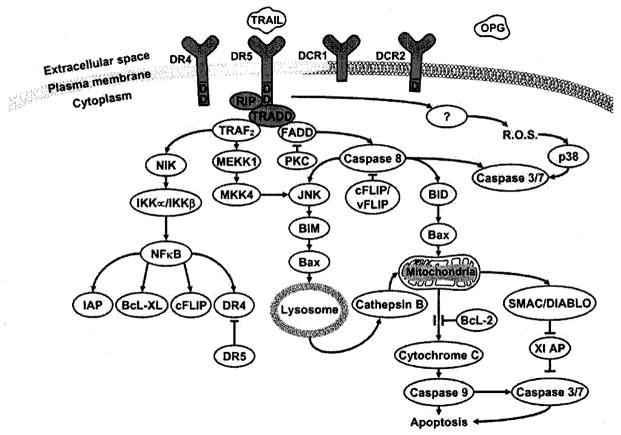

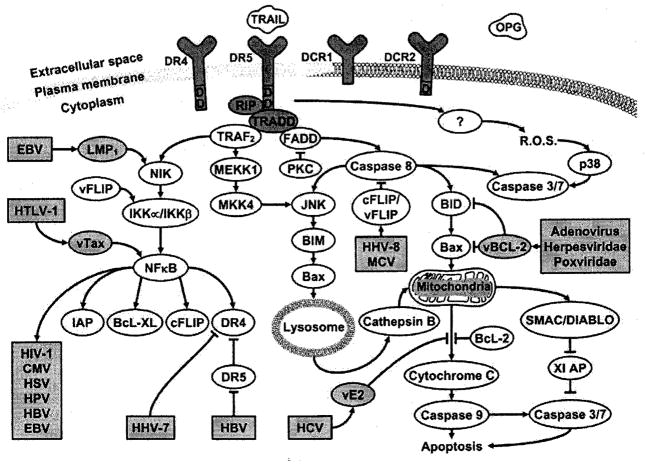

TRAIL’s signaling is complex with at least six known cascades converging and diverging and presumably contributing to an overall intracellular pro-apoptotic or anti-apoptotic milieu (Fig. 1). This complexity presents many opportunities for regulation by the host, and for manipulation by the virus (Fig. 2). Whether a virus evolves to initiate or prevent apoptosis of the host cell may depend on whether maximal viral replication and dissemination relies on cell death or cell preservation and latency. The multiplicity of the cascades may allow the host to bypass these viral attempts at manipulation.

Fig. (1).

Signaling pathways for caspase-dependent cell death initiated by TRAIL.

Fig. (2).

Signaling pathways for caspase-dependent cell death initiated by TRAIL. Some examples of viral interactions with the pathways are highlighted.

When either membrane bound or soluble TRAIL interacts with either functional receptor (TRAIL-R1 or TRAIL-R2), the intracellular death domain of the receptor recruits members of the death inducing signaling complex (DISC), which include Receptor-interacting protein (RIP) and TNF-receptor associated death domain protein (TRADD) [34]. The multiple cascades may diverge at TRADD, and this divergence may be dependent on the receptors’ association with lipid rafts or non-rafts. The multiple pro-apoptotic cascades all converge on the activation of the effecter caspases 3 and 7, which cleave DNA fragmentation factor 45 (DFF45), leading ultimately to the phenotypic characteristics of apoptotic cell death [35]. In BJAB cells, this process can take as little as 3 hours [36].

Fas-associated death domain (FADD) can associate with TRADD in the DISC and lead to activation of caspase 8 [34, 37]. This DISC formation is inhibited by Protein Kinase C by an unknown mechanism independent of the phosphorylation state of the TRAIL-Rs, FADD or TRADD [38]. Caspase 8 can activate caspases 3 and 7 directly or indirectly via lysosomal-dependent or independent pathways [39–41]. Caspase 8 can activate c-jun Amino Terminal Kinase (JNK), which leads to bcl-2 Interacting Mediator of Cell Death (BIM) activation. Activated BIM causes bcl-2-Associated X Protein (Bax) to translocate to the lysosome, which in turn causes cathepsin B release into the cytosol. Cathepsin B causes mitochondrial release of cytochrome c. Cytochrome c activates caspase 9, which activates caspases 3 and 7. Caspase 8 can also cleave BH3 Interacting Domain Death Agonist Protein (BID). Truncated BID causes Bax to translocate to the mitochondrial membrane causing release of cytochrome c [42] and Second Mitochondria-derived Activator of Caspase/DIABLO (SMAC/DIABLO) [43]. SMAC/DIABLO binds to X-linked Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein (XIAP) releasing its inhibitory hold on caspases 3 and 7.

RIP and TRADD can recruit TNF Receptor Associated Protein (TRAF2) to the DISC which can also lead to activation of JNK via Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase Kinase Kinase 1 (MEKK1) and MAP Kinase Kinase 4 (MKK4) [44, 45]. However, TRAF2 can also associate with NF-κB Inducing Kinase (NIK) to activate Iκ-B Kinases IKKα and IKKβ These inactivate IκB, releasing its inhibition of Nuclear Factor κB (NF-κB). NFκB can have immune activating, pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic effects [46]. For instance, NF-κB increases expression of TRAIL-R1 and R2 (pro-apoptotic), as well as cellular FLICE inhibitory protein (cFLIP) and Bcl-XL (both anti-apoptotic). Bcl-XL binds to the pro-apoptotic BH-3 proteins, such as Bak and Bax, preventing their activity. cFLIPs inhibit the activation of caspase 8. Other pro-survival and anti-apoptotic effects of TRAIL signaling through NF-κB, JNK and MAPK in cells resistant to TRAIL mediated apoptosis have been reviewed elsewhere [3].

There is also evidence that reactive oxygen species and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases are involved in the TRAIL signaling cascade upstream of caspase activity [47]. The relation of this pathway to the DISC is unknown.

There are multiple examples of viral manipulation of this signaling system. Human herpes virus 8 and Molluscum contagiosum virus both induce production of virally encoded vFLIPs by the infected cell [48]. Expression of vFLIPs in Jurkat cells render them TRAIL resistant. vFLIPSs accomplish this by both inhibiting caspase 8 and by activating NF-κB [49]. The herpesviridae, poxviridae and adenovirus encode for a viral version of Bcl-2 [50], a cellular protein that inhibits cytochrome c release from the mitochondria [51]. Some viruses alter the expression of TRAIL receptors, NFκB or cellular FLIP, which will be discussed below. The many examples of viral manipulation of the NFκB pathways has been reviewed elsewhere [52, 53]. Several viruses, including HIV, HTLV-1, HHV8 and EBV, use NFκB to stimulate their own replication [54]. The fact that numerous viruses have evolved ways to take advantage of or evade TRAIL induced apoptosis suggests that the killing effect of TRAIL has exerted a selective pressure on the viruses, lending evidence to the importance of TRAIL in the host immune response to viral infections.

CLUES TO THE FUNCTION OF TRAIL FROM TRAIL DEFICIENT MICE

While much has been learned about the in vitro functioning of TRAIL, its in vivo biologic function, or functions, is still controversial. Much has been inferred from results of experiments in TRAIL knockout mice, however the TRAIL (−/−) phenotype is not always consistent. Several investigators have explored this. Cretney et al. created TRAIL (−/−) mice which at baseline displayed no overt physiologic or anatomic abnormalities [55]. Liver mononuclear cells from these mice showed decreased cytotoxicity against TRAIL-sensitive renal adenocarcinoma and mammary carcinoma cells compared to wild type, and the TRAIL (−/−) mice were more susceptible to the development of liver, but not lung, metastases when injected with these same tumor cells. The TRAIL (−/−) mice were also more susceptible to chemical induced carcinogenesis. Sedger et al. also found no gross anatomic abnormalities in their TRAIL (−/−) mice, and they noted no alteration in serum biochemistries, peripheral blood hematology or composition or development of lymphoid tissues [56]. They found no increased susceptibility to transplanted T lymphoma cells, but did demonstrate decreased survival when exposed to B lymphoma cells, with most tumor involvement occurring in the liver. And despite TRAIL’s affinity for osteoprotegerin, TRAIL (−/−) mice did not demonstrate altered bone density. These experiments would suggest that TRAIL does not participate in the normal physiologic development or functioning of mice, but may play a role in tumor surveillance.

The picture is less clear when it comes to TRAIL (−/−) murine responses to experimental infectious and inflammatory conditions. Zheng et al. found that TRAIL (−/−) mice had less hepatocyte apoptosis and lower transaminase levels compared to wild type mice in response to concanavalin A-induced hepatitis [57]. They also challenged the TRAIL (−/−) mice with the intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes, and found decreased hepatitis and improved survival compared to wild type controls, despite similar bacterial loads early in disease. However, late in the disease, bacterial numbers were higher in WT than TRAIL (−/−) mice. These results seem counterintuitive, as one might expect TRAIL (−/−) mice to have impaired cell mediated immunity and reduced ability to kill cells infected with intracellular pathogens, and thus to have a higher pathogen burden and consequently a worse outcome. However, Zheng et al. also reported that TRAIL (−/−) mice have reduced lymphopenia and increased myeloid cell survival compared to WT suggesting that TRAIL might be involved in the lymphocyte depletion during Listeria infection [58].

Further insight into this seeming paradox regarding TRAIL’s physiologic role in the immune system may be gleaned from experiments in TRAIL receptor deficient mice by Diehl et al. [59]. Unlike humans, mice only have one full length active TRAIL receptor. No anatomic or hematologic abnormalities were found in unchallenged TRAIL-R (−/−) mice. Notably there was no difference in thymic negative selection of T cells in deficient mice compared to wild type. In contrast to the experiments described above with TRAIL deficient mice, TRAIL-R (−/−) mice had similar bacterial titers in the liver and spleen after infection with Listeria when compared to wild type. However, after infection with murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV), the TRAIL-R (−/−) mice had lower viral titers in the spleen, but not the liver or lung. There was no difference in the number or lytic activity of splenic NK cells or in their ability to produce IFNγ. They did note, though, increased levels of IL-12, IFNα, IFNβ and IFNγ in the TRAIL-R (−/−) mice compared to wild type after MCMV infection. This was secondary to increased cytokine production by the TRAIL-R (−/−) macrophages and dendritic cells. These results together suggest that deficiency in the TRAIL-R (−/−) may lead to an enhanced antiviral environment, and this suggests a dual function for TRAIL in the immune system. In vivo, therefore, TRAIL may act concurrently as both a negative regulator of the adaptive immune system as well an effector mechanism of the innate immune response to intracellular pathogens.

This anti-inflammatory property of TRAIL was also demonstrated by Song et al. in a mouse model of rheumatoid arthritis [60]. In mice with pharmacologically inhibited TRAIL function by pretreatment with soluble TRAIL-R2, the experimentally induced arthritis was actually worse than in controls. Treatment with soluble TRAIL-R2 was associated with an increase in lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production. In vitro experiments suggested that TRAIL was inhibitory to cell cycle progression independent of its pro-apoptotic effects. In similar experiments using TRAIL-R (−/−) mice, Lamhamdi-Chenadi et al. demonstrated worsened experimentally induced arthritis and streptozotocin induced diabetes compared to wild type controls [61]. This was associated with increased production of IFNγ and IL-2 by splenocytes isolated from the TRAIL-R (−/−) mice.

The relative importance of the two functions of TRAIL in the immune system – both as a pro-apoptotic effector of cell mediated immunity and as a negative immune regulator – is not clear. If TRAIL’s primary importance is to kill virally infected cells, then one would expect that increased TRAIL production in response to viral infection would lead to reduced viral production and improved disease outcome; however, this is not borne out by the experimental data described above. If, on the other hand, TRAIL’s primary function is in the negative regulation of the immune response to infection, then one would expect that TRAIL production in response to infection would lead to decreased cytokine production and lymphopenia, potentially resulting in increased viral replication or persistence and a worse disease outcome. The third possibility is that TRAIL acts in both capacities through its own negative feedback loop, down-regulating the expression of the very cytokines that stimulate its production.

TRAIL AND THE IMMUNE RESPONSE TO HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS

Clinical Evidence Supporting TRAIL Involvement in the Immune Response to HIV Infection

Several clinical lines of evidence suggest that TRAIL participates in the immune response to HIV infection. HIV infected individuals have higher serum levels of TRAIL than uninfected controls [62]. The serum level of TRAIL correlates positively with serum HIV viral load [63]. Likewise, TRAIL-R2 expression is increased in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from HIV infected patients [64]. Conversely, antiretroviral therapy decreases serum TRAIL levels [62] and expression of TRAIL-R2 [64]. Interestingly, poor CD4 T cell recovery in response to antiretroviral therapy has been associated with higher TRAIL-R1 expression on T cells [65], and to a polymorphism in the TRAIL gene [66].

In Vitro Evidence Supporting TRAIL Involvement in the Immune Response to HIV Infection

Some in vitro evidence also suggests that TRAIL is involved in the immune response to HIV infection. HIV infected dendritic cells can induce apoptosis in HIV uninfected CD4 T cell lines via FasL, TNFalpha and TRAIL [67]. HIV-1 Tat protein increases TRAIL expression and secretion in monocytes [68] and macrophages [69]. When uninfected donor CD4 T cells are infected with HIV, they show increased TRAIL and TRAIL-R2 expression [64]. Treatment of Jurkat T cells with HIV gp120 results in increased TRAIL receptor expression and confers increased TRAIL susceptibility [70].

TRAIL can reduce HIV burden in vitro. Treatment of HIV infected monocyte derived macrophages and peripheral blood lymphocytes with leucine-zippered TRAIL results in decreased HIV burden as measured by viral RNA and p24 antigen production following limiting dilution micro co-culture [71]. Treatment of NK cells with IL-15 upregulates TRAIL expression, and treated NK cells are able to reduce the burden of replication-competent HIV virions in autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells [72].

Controversies Regarding the Role and Regulation of TRAIL in HIV Infection

While there is suggestive clinical and in vitro evidence that TRAIL is involved in the immune response to HIV infection, it is not yet clear whether TRAIL mediated apoptosis is causally relate to the subsequent CD4+ T cell decline that is the hallmark of progression to clinical disease. HIV infected dendritic cells can induce apoptosis in HIV uninfected CD4+ T cells via TRAIL [67], the so-called ‘bystander killing’ effect. On the other hand, TRAIL resistance in Jurkat T cell lines can be achieved with transfection of the HIV-1 Tat protein [73].

The ultimate role of the virus itself in the induction of TRAIL expression in infected patients is unclear as there seem to be multiple regulatory influences. The above noted increase in TRAIL expression following experimental HIV infection of uninfected donor CD4 T cells is dependent on type 1 interferons [64]. HIV-1 stimulated plasmacytoid dendritic cells produce type 1 interferons, whereas antagonizing IFN alpha and beta can inhibit CD4 T cell TRAIL expression and function [74]. As noted earlier, bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulates TRAIL expression in monocytes and macrophages. Circulating LPS levels are increased in chronically HIV-infected individuals leading to chronic stimulation of CD14+ monocytes and macrophages [75]. Moreover, higher circulating levels of LPS are associated with elevated plasma IFNα [75]. It is possible that at least some of the increased expression of TRAIL seen in HIV infection is secondary to the chronic immune activation associated with the disease and not directly to viral infection of TRAIL producing cells.

TRAIL AND VIRAL HEPATITIS

It is generally accepted that most of the inflammation and clinical disease associated with the hepatitis viruses is due to the immune response to the viral infection, and that apoptosis plays a significant role in that pathology [76]. The role of TRAIL in hepatocyte apoptosis in response to viral infection is the subject of much research, however there are several limitations to the data presented thus far that make a definitive statement regarding this role difficult. First of all, normal human hepatocytes are somewhat susceptible to TRAIL mediated apoptosis, at least in vitro; however, high doses of TRAIL are required to achieve this effect [77]. Second, seemingly disparate findings are reported in different infection models and seem to be dependent on the cell lines used. Finally, the lack of cultiviable Hepatitis C virus limits the in vitro studies that can be done at the present time for one of the major causes of viral hepatitis in the world today. However, as with HIV, there are several lines of evidence that supports TRAIL’s role in the immune response to Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C viruses.

Clinical Evidence in Hepatitis B Viral Infection

Serum levels of soluble TRAIL [78–81] and T cell-associated membrane bound TRAIL [80, 81] are elevated in Hepatitis B infected patients compared to controls. Patients with chronic active Hepatitis B have higher sTRAIL levels than patients with HBV-related cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma and HBV carriers [79]. Elevated levels of both sTRAIL and membrane bound TRAIL are both correlated with elevated laboratory markers of hepatitis, including serum transaminases and total bilirubin [78, 80].

In Vivo Evidence in Hepatitis B Viral Infection

One study demonstrated in a mouse model of acute Hepatitis B infection decreased serum transaminase levels and hepatocyte apoptosis with administration of soluble TRAIL-R2 [82]. Decreased hepatitis was also seen in Bax knockdown mice infected with Hepatitis B [82].

In Vitro Evidence in Hepatitis B Viral Infection

Two groups have examined the effect of transfection of the whole HBV genome into a human hepatoma cell line (HepG2) with disparate results. One group found that HBV transfection decreased TRAIL sensitivity by decreasing TRAIL receptor expression and increasing cFLIP [83]. Another group found just the opposite – that transfection of the HBV genome, particularly the HBx gene, increased TRAIL-R1 expression and thereby increased TRAIL sensivity [84]. The former group then transfected a different human hepatoma cell line (BEL7402) with the HBV genome or the HBx gene, and they demonstrated increased TRAIL sensitivity but no change in TRAIL receptor or cFLIP expression, but instead increased Bax expression [82]. These conflicting results may be partially explained by the use of different cell lines, as well as different preparations of TRAIL. However, the use of transformed cell lines in the infection model may be an issue in of itself. Immunohistochemical staining of pathology specimens of HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma tissue show a relative decrease in TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 expression when compared to non-malignant, but presumably HBV infected, surrounding tissue [84].

Some of the more convincing data associating TRAIL and the immune response to HBV infection come from Dunn et al. [85]. They found consistently elevated circulating levels of IFNα and IL-8 in 14 eAg negative chronic hepatitis B patients when compared to healthy controls. Moreover, the levels of these cytokines correlated with HBV viral load and liver inflammation during acute hepatitis flares. During these flares, there were more circulating activated NK cells, more TRAIL expression on the activated NK cells, and an enrichment of intrahepatic, activated, TRAIL expressing NK cells. NK cells isolated from these patients exposed in vitro to this level of IFNα showed increased TRAIL expression. HepG2 cells showed increased TRAIL-R2 in response to IL-8, and decreased TRAIL-R4 expression to IFNα. The cytotoxicity of PBMCs on HepG2 cells was maximized by pretreating the HepG2 cells with IL-8 and the PBMCs with IFNα [85].

Clinical Evidence in Hepatitis C Infection

As in HIV and Hepatitis B infected patients, sTRAIL levels are higher in Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infected individuals than in uninfected controls [86]. sTRAIL levels increase after treatment with interferon in HCV infected patients [86]. Liver biopsies from HCV infected patients show TRAIL and TRAIL-R expression by immunohistochemistry in periportal hepatocytes, and in some, the infiltrating lymphocytes express TRAIL, and the intensity of staining increases with disease progression [87]. Increased TRAIL expression was also seen in livers of HCV infected patients with steatosis [88].

In Vitro Evidence in Hepatitis C Infection

The role of apoptosis in the pathogenesis of Hepatitis C infection has been reviewed in detail elsewhere [89]. Table 1 presents the major results of studies in the literature focusing on the role of TRAIL as a mediator of apoptosis, and the variables that may have affected the disparate results.

Table 1.

In Vitro Evidence Linking TRAIL and Hepatitis C Infection

| HCV Infection Model | Cell Line | TRAIL Preparation, Dose | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCVJFH-1 | Human hepatoma (LH86) | None. TRAIL knockdown decreased HCV induced apoptosis. | Increased TRAIL, TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 expression. Increased TRAIL susceptibility. Induced hepatocyte production of IFNβ. | [106] |

| Conditional expression of HCV-1a open reading frame | Nontransformed human hepatocytes (HH4) | Leucine zippered TRAIL, 0–200 ng/mL for 8 hours. | No change in TRAIL susceptibility. Increased NFκB expression. | [107] |

| Transfection of HCV core protein | Human hepatoma (Huh-7) | His-tagged TRAIL, 250–1500 ng/mL for 6 hours | Increased TRAIL susceptibility despite no change in TRAIL-R1 or TRAIL-R2 expression. | [108] |

| Transfection of HCV E2 protein | Human hepatoma (Huh-7) | TRAIL preparation not mentioned, 200 ng/mL for 1–2 hours | Decreased TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 expression. Decreased TRAIL susceptibility. | [109] |

| Clinical HCV infection | Explanted Liver Tissue | Unspecified | Increased TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 expression. Increased TRAIL susceptibility. | [110] |

TRAIL AND THE IMMUNE RESPONSE TO OTHER VIRUSES

There is a growing body of in vitro evidence that TRAIL participates in the immune response to other viruses. Some of these will be reviewed below.

Cytomegalovirus

Experiments involving CMV potentially point toward the dual nature of TRAIL’s role in the immune system, both as an apoptosis inducer and a negative immune regulator. CMV infection of human fibroblasts [90] and colonic epithelial cells [91] upregulates expression of TRAIL and TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 and renders the respective cells TRAIL sensitive. Moreover, TRAIL treatment of human fibroblasts infected with CMV reduces the recoverable virus after cell death [90]. These results suggest TRAIL’s function as an immune effected However, infection of dendritic cells with CMV upregulates FasL and TRAIL expression, enabling dendritic cells to delete activated T lymphocytes [92]. This may play a role in the immunosuppressive effect of CMV infection in vivo, seen most acutely in transplant recipients with reactivation CMV disease who are at higher risk for secondary bacterial and fungal infections [93, 94].

Epstein-Barr Virus

Epstein-Barr Virus is an example of virus induced resistance to TRAIL mediated killing. Mouzakiti and Packham tested 12 Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) cell lines for TRAIL susceptibility [95]. 4/5 BL cell lines not infected with Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) were susceptible to TRAIL; however, only 1/7 EBV-infected cells lines were susceptible. Tafuku et al. demonstrated that EBV infected BL cell lines were resistant to TRAIL, and that this resistance was reversed by NF-κB inhibitors [96]. Snow et al. demonstrated similar resistance to TRAIL in EBV infected BJAB cells, and that this resistance was mediated by activation of NF-κB and upregulation of cFLIP [97]. Snow et al. also found TRAIL resistance in EBV+ spontaneous lymphoblastoid cell lines (SLCL) from patients with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder [98]. The SLCL cells were shown to express TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 on the cell surface, however they demonstrated reduced TRAIL-R clustering and reduced caspase 8 activity after treatment with TRAIL when compared to EBV uninfected BJAB cells.

Influenza Virus

There have been two conflicting reports on the role of TRAIL and the immune response to influenza virus. In vitro infection of human lung cancer cells with influenza virus resulted in an NFκB dependent upregulation of TRAIL expression in infected cells [99]. No effect was seen on TRAIL-R1 or TRAIL-R2 expression. Interestingly, treatment with TRAIL-R2-Fc decreased virus production. This suggests that TRAIL acts in a proviral capacity, potentially through NFκB mediated viral transactivation, and that TRAIL increases viral production. Similarly, increased TRAIL expression was seen in mouse lung, NK cells and CD4 and CD8 T cells after in vivo infection with influenza virus [100]. However, in this mouse model, treatment with anti-TRAIL antibody decreased viral clearance, suggesting that TRAIL has an in vivo antiviral effect in influenza viral infection.

Measles Virus

Early work has indicated that measles virus infection of dendritic cells upregulates TRAIL expression and cytotoxicity to uninfected T cells [101, 102]. This may be responsible in the lymphopenia [102] and high secondary infection rate [101] seen with clinical measles infections, and argues that in this setting, TRAIL may act as a negative immune regulator.

Other Viruses

Table 2 summarizes some of the early in vitro findings with TRAIL and other viral infections.

Table 2.

In Vitro Experiments Involving TRAIL and RSV, Ebola, HHV-7, Reovirus and HTLV-1

| Virus | Cell Line | Effect of In Vitro Infection | Postulated Role of TRAIL | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory Syncytial Virus | Human airway cells | Increased TRAIL, TRAIL-R 1 and TRAIL-R2 expression. Increased TRAIL sensitivity. | Antiviral mediator | [111] |

| Ebola Virus | Adherent human monocytes/macrophages | Increased TRAIL expression. | Immune regulator | [112] |

| Human Herpes Virus-7 | Activated CD4 T cells | Increased TRAIL and decreased TRAIL-R1 expression. Apoptosis seen mostly in bystander cells. | Immune regulator | [113] |

| Reovirus | Human Embryonic Kidney, Mouse Connective Tissue | Increased TRAIL and TRAIL-R2 expression. Increased TRAIL sensitivity. | Antiviral mediator | [114] |

| Human T-lymphotropic Virus 1 | Human T cells | Increased TRAIL, decreased TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 expression. Induced TRAIL resistance. | Viral resistance of antiviral mediator | [115] |

TRAIL BASED THERAPIES

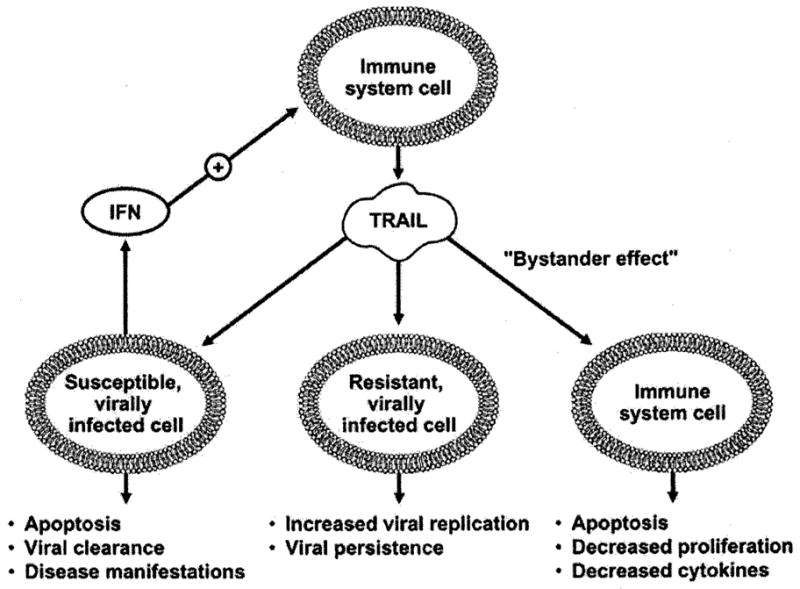

The host immune response to viral infections is complex, and integrates both the innate and adaptive immune response with a plethora of cytokines, particularly the interferons, and highly regulated cellular processes such as apoptosis [103]. Multiple lines of evidence are emerging that TRAIL plays an active role in this immune response to viral infections. TRAIL appears to have a dual role in the immune system, one as an inducer of apoptosis in cancer cells and virally infected cells, and the other as a negative immune regulator, inducing apoptosis in uninfected lymphocytes, downregulating cytokine production and inhibiting inflammation (Fig. 3). Whether local expression of TRAIL or elevated levels of circulating TRAIL act in a proviral or antiviral capacity, or both, likely depends on multiple factors, including the basic biology of the virus, the immune competency of the host, and the state of immune activation at baseline and which is caused by acute or chronic viral infections. Further understanding of these complex issues is crucial, because clinical development of TRAIL agonist therapy in cancer treatment is proceeding rapidly as the concerns about potential hepatotoxicity in humans are declining [5].

Fig. (3).

Proposed roles of TRAIL in the immune response to viral infections.

Despite the early concerns with the in vitro susceptibility of normal human hepatocytes to TRAIL mediated apoptosis, agonistic monoclonal antibodies to TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 have not shown this effect in vivo [104]. Several Phase 1 and 2 clinical trials of these monoclonal antibodies to TRAIL-R1 (mapatumumab) and TRAIL-R2 (lexatumumab), both products of Human Genome Sciences (Rockville, MD), have already been completed. Early clinical trials with mapatumumab in patients with advanced solid tumors [116], non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma [117] and non-small cell lung carcinoma [118], and with lexatumumab in patients with advanced solid malignancies [105, 119], have not shown an increase in hepatitis in treated patients compared to controls. While these early clinical trials of TRAIL receptor agonist therapy also have not demonstrated a predisposition to acquiring new viral infections or reactivating latent infections, close monitoring will need to be done both in future clinical trials and in postmarketing surveillance if these novel therapies come to fruition. Increasing clinical experience with TRAIL agonist therapy in cancer patients, combined with continuing efforts to better define TRAIL’s role in the pathogenesis of individual viral infections, may one day lead to a novel class of antiviral agents, comprised of either TRAIL agonists or antagonists, depending on the targeted virus.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Andrew Badley is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI62261 and R01 AI403840) and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund’s Clinical Scientist Award in Translational Research (ID#1005160).

References

- 1.Wiley SR, Schooley K, Smolak PJ, Din WS, Huang CP, Nicholl JK, Sutherland GR, Smith TD, Rauch C, Smith CA, Goodwin RG. Immunity. 1995;3:673–82. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitti RM, Marsters SA, Ruppert S, Donahue CJ, Moore A, Ashkenazi A. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12687–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimberley FC, Screaton GR. Cell Res. 2004;14:359–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broker LE, Kruyt FA, Giaccone G. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3155–62. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gajewski TF. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1305–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.9804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krieg A, Krieg T, Wenzel M, Schmitt M, Ramp U, Fang B, Gabbert HE, Gerharz CD, Mahotka C. Br J Cancer. 2003;6:918–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cha SS, Kim MS, Choi YH, Sung BJ, Shin NK, Shin HC, Sung YC, Oh BH. Immunity. 1999;11:253–61. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mongkolsapaya J, Grimes JM, Chen N, Xu XN, Stuart DI, Jones EY, Screaton GR. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:1048–53. doi: 10.1038/14935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanner MA, Everett CL, Youvan DC. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1628–31. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.4.1628-1631.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trabzuni D, Famulski KS, Ahmad M. Biochem J. 2000;350:505–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Modrek B, Lee C. Nat Genet. 2002;30:13–9. doi: 10.1038/ng0102-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mariani SM, Krammer PH. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1492–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199805)28:05<1492::AID-IMMU1492>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zamai L, Ahmad M, Bennett IM, Azzoni L, Alnemri ES, Perussia B. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2375–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffith TS, Wiley SR, Kubin MZ, Sedger LM, Maliszewski CR, Fanger NA. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1343–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.8.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnsen AC, Haux J, Steinkjer B, Nonstad U, Egeberg K, Sundan A, Ashkenazi A, Espevik T. Cytokine. 1999;11:664–72. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kayagaki N, Yamaguchi N, Nakayama M, Takeda K, Akiba H, Tsutsui H, Okamura H, Nakanishi K, Okumura K, Yagita H. J Immunol. 1999;163:1906–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato K, Hida S, Takayanagi H, Yokochi T, Kayagaki N, Takeda K, Yagita H, Okumura K, Tanaka N, Taniguchi T, Ogasawara K. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3138–46. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3138::aid-immu3138>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halaas O, Vik R, Ashkenazi A, Espevik T. J Immunol. 2000;51:244–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stetson DB, Medzhitov R. Immunity. 2006;25:373–81. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan G, O’Rourke K, Chinnaiyan AM, Gentz R, Ebner R, Ni J, Dixit VM. Science. 1997;276:111–3. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan G, Ni J, Wei YF, Yu G, Gentz R, Dixit VM. Science. 1997;277:815–8. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walczak H, Degli-Esposti MA, Johnson RS, Smolak PJ, Waugh JY, Boiani N, Timour MS, Gerhart MJ, Schooley KA, Smith CA, Goodwin RG, Rauch CT. EMBO J. 1997;16:5386–97. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Degli-Esposti MA, Smolak PJ, Walczak H, Waugh J, Huang CP, DuBose RF, Goodwin RG, Smith CA. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1165–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacFarlane M, Ahmad M, Srinivasula SM, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Cohen GM, Alnemri ES. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25417–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mongkolsapaya J, Cowper AE, Xu XN, Morris G, McMichael AJ, Bell JI, Screaton GR. J Immunol. 1998:160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marsters SA, Sheridan JP, Pitti RM, Huang A, Skubatch M, Baldwin D, Yuan J, Gurney A, Goddard AD, Godowski P, Ashkenazi A. Curr Biol. 1997;7:1003–6. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Degli-Esposti MA, Dougall WC, Smolak PJ, Waugh JY, Smith CA, Goodwin RG. Immunity. 1997;7:813–20. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80399-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan G, Ni J, Yu G, Wei YF, Dixit VM. FEBS Lett. 1998;424:41–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emery JG, McDonnell P, Burke MB, Deen KC, Lyn S, Silverman C, Dul E, Appelbaum ER, Eichman C, DiPrinzio R, Dodds RA, James IE, Rosenberg M, Lee JC, Young PR. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14363–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shipman CM, Croucher PI. Cancer Res. 2003;63:912–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Truneh A, Sharma S, Silverman C, Khandekar S, Reddy MP, Deen KC, McLaughlin MM, Srinivasula SM, Livi GP, Marshall LA, Alnemri ES, Williams WV, Doyle ML. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23319–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910438199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muhlenbeck F, Schneider P, Bodmer JL, Schwenzer R, Hauser A, Schubert G, Scheurich P, Moosmayer D, Tschopp J, Wajant H. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32208–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wajant H, Moosmayer D, Wuest T, Bartke T, Gerlach E, Schonherr U, Peters N, Scheurich P, Pfizenmaier K. Oncogene. 2001;20:4101–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaudhary PM, Eby M, Jasmin A, Bookwalter A, Murray J, Hood L. Immunity. 1997;7:821–30. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu X, Li P, Widlak P, Zou H, Luo X, Garrard WT, Wang X. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8461–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamada H, Tada-Oikawa S, Uchida A, Kawanishi S. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;265:130–3. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider P, Thome M, Burns K, Bodmer JL, Hofmann K, Kataoka T, Holler N, Tschopp J. Immunity. 1997;7:831–6. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harper N, Hughes MA, Farrow SN, Cohen GM, MacFarlane M. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44338–47. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muhlenbeck F, Haas E, Schwenzer R, Schubert G, Grell M, Smith C, Scheurich P, Wajant H. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33091–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.33091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herr I, Wilhelm D, Meyer E, Jeremias I, Angel P, Debatin KM. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:130–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Werneburg NW, Guicciardi ME, Bronk SF, Kaufmann SH, Gores GJ. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28960–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705671200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park IC, Park MJ, Woo SH, Lee KH, Lee SH, Rhee CH, Hong SI. Cytokine. 2001;15:166–70. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deng Y, Lin Y, Wu X. Genes Dev. 2002;16:33–45. doi: 10.1101/gad.949602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu WH, Johnson H, Shu HB. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30603–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin Y, Devin A, Cook A, Keane MM, Kelliher M, Lipkowitz S, Liu ZG. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6638–45. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6638-6645.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ravi R, Bedi GC, Engstrom LW, Zeng Q, Mookerjee B, Gelinas C, Fuchs EJ, Bedi A. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:409–16. doi: 10.1038/35070096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee MW, Park SC, Yang YG, Yim SO, Chae HS, Bach JH, Lee HJ, Kim KY, Lee WB, Kim SS. FEBS Lett. 2002;512:313–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thome M, Schneider P, Hofmann K, Fickenscher H, Meinl E, Neipel F, Mattmann C, Burns K, Bodmer JL, Schroter M, Scaffidi C, Krammer PH, Peter ME, Tschopp J. Nature. 1997;386:517–21. doi: 10.1038/386517a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guasparri I, Keller SA, Cesarman E. J Exp Med. 2004;199:993–1003. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 50.Cuconati A, White E. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2465–78. doi: 10.1101/gad.1012702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun SY, Yue P, Zhou JY, Wang Y, Choi Kim HR, Lotan R, Wu GS. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:788–97. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bowie AG, Zhan J, Marshall WL. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:1099–108. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hiscott J, Nguyen TLA, Arguello M, Nakhaei P, Paz S. Oncogene. 2006;25:6844–6867. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hiscott J, Kwon H, Genin P. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:143–51. doi: 10.1172/JCI11918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cretney E, Takeda K, Yagita H, Glaccum M, Peschon JJ, Smyth MJ. J Immunol. 2002;168:1356–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sedger LM, Glaccum MB, Schuh JC, Kanaly ST, Williamson E, Kayagaki N, Yun T, Smolak P, Le T, Goodwin R, Gliniak B. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2246–54. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200208)32:8<2246::AID-IMMU2246>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng SJ, Wang P, Tsabary G, Chen YH. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:58–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI200419255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zheng SJ, Jiang J, Shen H, Chen YH. J Immunol. 2004;173:5652–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diehl GE, Yue HH, Hsieh K, Kuang AA, Ho M, Morici LA, Lenz LL, Cado D, Riley LW, Winoto A. Immunity. 2004;21:877–89. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Song K, Chen Y, Goke R, Wilmen A, Seidel C, Goke A, Hilliard B, Chen Y. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1095–104. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lamhamedi-Cherradi SE, Zheng SJ, Maguschak KA, Peschon J, Chen YH. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:255–60. doi: 10.1038/ni894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Herbeuval JP, Boasso A, Grivel JC, Hardy AW, Anderson SA, Dolan MJ, Chougnet C, Lifson JD, Shearer GM. Blood. 2005;105:2458–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gibellini D, Re MC, Ponti C, Vitone F, Bon I, Fabbri G, Grazia, Di lasio M, Zauli G. J Cell Physiol. 2005;203:547–56. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Herbeuval JP, Grivel JC, Boasso A, Hardy AW, Chougnet C, Dolan MJ, Yagita H, Lifson JD, Shearer GM. Blood. 2005;106:3524–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hansjee N, Kaufmann GR, Strub C, Weber R, Battegay M, Erb P. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36:671–7. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200406010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haas DW, Geraghty DE, Andersen J, Mar J, Motsinger AA, D’Aquila RT, Unutmaz D, Benson CA, Ritchie MD, Landay A. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1098–107. doi: 10.1086/507313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lichtner M, Maranon C, Vidalain PO, Azocar O, Hanau D, Lebon P, Burgard M, Rouzioux C, Vullo V, Yagita H, Rabourdin-Combe C, Servet C, Hosmalin A. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20:175–82. doi: 10.1089/088922204773004897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang Y, Tikhonov I, Ruckwardt TJ, Djavani M, Zapata JC, Pauza CD, Salvato MS. J Virol. 2003;77:6700–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6700-6708.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang M, Li X, Pang X, Ding L, Wood O, Clouse K, Hewlett I, Dayton AI. J Biomed Sci. 2001;8:290–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02256603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lum JJ, Schnepple DJ, Badley AD. Aids. 2005;19:1125–33. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000176212.16205.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lum JJ, Pilon AA, Sanchez-Dardon J, Phenix BN, Kim JE, Mihowich J, Jamison K, Hawley-Foss N, Lynch DH, Badley AD. J Virol. 2001;75:11128–36. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.11128-11136.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lum JJ, Schnepple DJ, Nie Z, Sanchez-Dardon J, Mbisa GL, Mihowich J, Hawley N, Narayan S, Kim JE, Lynch DH, Badley AD. J Virol. 2004;78:6033–42. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.6033-6042.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gibellini D, Re MC, Ponti C, Maldini C, Celeghini C, Cappellini A, La Placa M, Zauli G. Cell Immunol. 2001;207:89–99. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2000.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Herbeuval JP, Hardy AW, Boasso A, Anderson SA, Dolan MJ, Dy M, Shearer GM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13974–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505251102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, Kazzaz Z, Bomstein E, Lambotte O, Altmann D, Blazar BR, Rodriguez B, Teixeira-Johnson L, Landay A, Martin JN, Hecht FM, Picker LJ, Lederman MM, Deeks SG, Douek DC. Nat Med. 2006;12:1365–71. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Malhi H, Gores GJ, Lemasters JJ. Hepatology. 2006;43:S31–44. doi: 10.1002/hep.21062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mori E, Thomas M, Motoki K, Nakazawa K, Tahara T, Tomizuka K, Ishida I, Kataoka S. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:203–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yue FE, Liu DY, Song J, Zhang LN. Zhonghua Shi Yan He Lin Chuang Bing Du Xue Za Zhi. 2005;19:146–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Han LH, Sun WS, Ma CH, Zhang LN, Liu SX, Zhang Q, Gao LF, Chen YH. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:1077–80. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i6.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen GY, He JQ, Lu GC, Li MW, Xu CH, Fan WW, Zhou C, Chen Z. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4090–3. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i26.4090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen GY, He JQ, Lv GC, Li MW, Xu CH, Fan WW, Chen Z. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2004;12:284–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liang X, Liu Y, Zhang Q, Gao L, Han L, Ma C, Zhang L, Chen YH, Sun W. J Immunol. 2007;178:503–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Han L, Sun W, Ma C, Zhang L, Cao Y, Song J, Chen Y. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2002;82:597–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yano Y, Hayashi Y, Nakaji M, Nagano H, Seo Y, Ninomiya T, Yoon S, Wada A, Hirai M, Kim SR, Yokozaki H, Kasuga M. Int J Mol Med. 2003;11:499–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dunn C, Brunetto M, Reynolds G, Christophides T, Kennedy PT, Lampertico P, Das A, Lopes AR, Borrow P, Williams K, Humphreys E, Afford S, Adams DH, Bertoletti A, Maini MK. J Exp Med. 2007;204:667–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pelli N, Torre F, Delfino A, Basso M, Picciotto A. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26:119–23. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Saitou Y, Shiraki K, Fuke H, Inoue T, Miyashita K, Yamanaka Y, Yamaguchi Y, Yamamoto N, Ito K, Sugimoto K, Nakano T. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:1066–73. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mundt B, Wirth T, Zender L, Waltemathe M, Trautwein C, Manns MP, Kuhnel F, Kubicka S. Gut. 2005;54:1590–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.056929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fischer R, Baumert T, Blum HE. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4865–72. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i36.4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sedger LM, Shows DM, Blanton RA, Peschon JJ, Goodwin RG, Cosman D, Wiley SR. J Immunol. 1999;163:920–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Strater J, Walczak H, Pukrop T, Von Muller L, Hasel C, Kornmann M, Mertens T, Moller P. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:659–66. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Raftery MJ, Schwab M, Eibert SM, Samstag Y, Walczak H, Schonrich G. Immunity. 2001;15:997–1009. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Falagas ME, Snydman DR, Griffith J, Werner BG. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:468–74. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.3.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.George MJ, Snydman DR, Werner BG, Griffith J, Falagas ME, Dougherty NN, Rubin RH. Am J Med. 1997;103:106–13. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)80021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mouzakiti A, Packham G. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:61–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tafuku S, Matsuda T, Kawakami H, Tomita M, Yagita H, Mori N. Eur J Haematol. 2006;76:64–74. doi: 10.1111/j.0902-4441.0000.t01-1-EJH2345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Snow AL, Lambert SL, Natkunam Y, Esquivel CO, Krams SM, Martinez OM. J Immunol. 2006;177:3283–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Snow AL, Vaysberg M, Krams SM, Martinez OM. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:976–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wurzer WJ, Ehrhardt C, Pleschka S, Berberich-Siebelt F, Wolff T, Walczak H, Planz O, Ludwig S. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30931–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403258200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ishikawa E, Nakazawa M, Yoshinari M, Minami M. J Virol. 2005;79:7658–63. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7658-7663.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vidalain PO, Azocar O, Lamouille B, Astier A, Rabourdin-Combe C, Servet-Delprat C. J Virol. 2000;74:556–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.556-559.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vidalain PO, Azocar O, Rabourdin-Combe C, Servet-Delprat C. Immunobiology. 2001;204:629–38. doi: 10.1078/0171-2985-00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Barber GN. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:113–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ichikawa K, Liu W, Zhao L, Wang Z, Liu D, Ohtsuka T, Zhang H, Mountz JD, Koopman WJ, Kimberly RP, Zhou T. Nat Med. 2001;7:954–60. doi: 10.1038/91000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Plummer R, Attard G, Pacey S, Li L, Razak A, Perrett R, Barrett M, Judson I, Kaye S, Fox NL, Halpern W, Corey A, Calvert H, de Bono J. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6187–94. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhu H, Dong H, Eksioglu E, Hemming A, Cao M, Crawford JM, Nelson DR, Liu C. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1649–59. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tang W, Lazaro CA, Campbell JS, Parks WT, Katze MG, Fausto N. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1831–46. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chou AH, Tsai HF, Wu YY, Hu CY, Hwang LH, Hsu PI, Hsu PN. J Immunol. 2005;174:2160–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lee SH, Kim YK, Kim CS, Seol SK, Kim J, Cho SY, Song L, Bartenschlager R, Jang SK. J Immunol. 2005;175:8226–35. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Volkmann X, Fischer U, Bahr MJ, Ott M, Lehner F, Macfarlane M, Cohen GM, Manns MP, Schulze-Osthoff K, Bantel H. Hepatology. 2007;46:1498–508. doi: 10.1002/hep.21846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kotelkin A, Prikhod’ko EA, Cohen JI, Collins PL, Bukreyev A. J Virol. 2003;77:9156–72. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9156-9172.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hensley LE, Young HA, Jahrling PB, Geisbert TW. Immunol Lett. 2002;80:169–79. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(01)00327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Secchiero P, Mirandola P, Zella D, Celeghini C, Gonelli A, Vitale M, Capitani S, Zauli G. Blood. 2001;98:2474–81. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Clarke P, Meintzer SM, Gibson S, Widmann C, Garrington TP, Johnson GL, Tyler KL. J Virol. 2000;74:8135–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.8135-8139.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chang KO, Sosnovtsev SS, Belliot G, Wang Q, Saif LJ, Green KY. J Virol. 2005;79:1409–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1409-1416.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mita MM, Tolcher AW, Patnaik A, Hill M, Fox NL, Corey A, Blake L, Padavic KM, Meropol NJ, Rowinsky EK, Cohen RB. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2005;(46):Abstract #544. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Younes A, Vose J, Zelenetz AD, Czuczman MS. Results of a Phase 2 trial of HGS-ETR1 (agonistic human monoclonal antibody to TRAIL receptor 1) in subjects with relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) (ETR1-HM01). 47th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology.2005. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bonomi P, Greco FA. Results of a Phase 2 trial of HGS-ETR1 (agonistic human monoclonal antibody to TRAIL receptor 1) in subjects with relapsed/recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. 11th World Conference on Lung Cancer; 2005. p. Abstract #1851. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sikic BI. A Phase 1b study to assess the safety of lexatumumab, a human monoclonal antibody that activates TRAIL-R2, in combination with gemcitabine, pemetrexed, doxorubicin or FLOFIRI. AACR-NCI-EORTC, International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics; 2007. p. Abstract #B72. [Google Scholar]