ABSTRACT

Cryptococcosis is a multifaceted fungal infection with variable clinical presentation and outcome. As in many infectious diseases, this variability is commonly assigned to host factors. To investigate whether the diversity of Cryptococcus neoformans clinical (ClinCn) isolates influences the interaction with host cells and the clinical outcome, we developed and validated new quantitative assays using flow cytometry and J774 macrophages. The phenotype of ClinCn-macrophage interactions was determined for 54 ClinCn isolates recovered from cerebrospinal fluids (CSF) from 54 unrelated patients, based on phagocytic index (PI) and 2-h and 48-h intracellular proliferation indexes (IPH2 and IPH48, respectively). Their phenotypes were highly variable. Isolates harboring low PI/low IPH2 and high PI/high IPH2 values were associated with nonsterilization of CSF at week 2 and death at month 3, respectively. A subset of 9 ClinCn isolates with different phenotypes exhibited variable virulence in mice and displayed intramacrophagic expression levels of the LAC1, APP1, VAD1, IPC1, PLB1, and COX1 genes that were highly variable among the isolates and correlated with IPH48. Variation in the expression of virulence factors is thus shown here to depend on not only experimental conditions but also fungal background. These results suggest that, in addition to host factors, the patient’s outcome can be related to fungal determinants. Deciphering the molecular events involved in C. neoformans fate inside host cells is crucial for our understanding of cryptococcosis pathogenesis.

IMPORTANCE

Cryptococcus neoformans is a life-threatening human fungal pathogen that is responsible for an estimated 1 million cases of meningitis/year, predominantly in HIV-infected patients. The diversity of infecting isolates is well established, as is the importance of the host factors. Interaction with macrophages is a major step in cryptococcosis pathogenesis. How the diversity of clinical isolates influences macrophages’ interactions and impacts cryptococcosis outcome in humans remains to be elucidated. Using new assays, we uncovered how yeast-macrophage interactions were highly variable among clinical isolates and found an association between specific behaviors and cryptococcosis outcome. In addition, gene expression of some virulence factors and intracellular proliferation were correlated. While many studies have established that virulence factors can be differentially expressed as a function of experimental conditions, our study demonstrates that, under the same experimental conditions, clinical isolates behaved differently, a diversity that could participate in the variable outcome of infection in humans.

Introduction

With 1 million cases per year and 700,000 annual deaths, cryptococcosis is one of the most frequent invasive fungal infections worldwide (1). It occurs mostly in patients with immune defects, especially those with AIDS, but also non-HIV immunocompromised patients (e.g., patients with sarcoidosis, solid organ transplant patients, and patients under steroid or other immunosuppressive therapy) (2). Cryptococcosis is a multifaceted pathology in terms of clinical presentation and outcome, with meningoencephalitis being the most frequent and severe presentation. Despite undergoing 3 months of adequate antifungal treatment, 15 to 20% patients will die from cryptococcosis (3). This infection is due to the haploid yeasts Cryptococcus neoformans, including varieties grubii (serotype A) and neoformans (serotype D), and Cryptococcus gattii. C. neoformans propagates by budding and is also capable of sexual multiplication and same-sex mating, which contributes to the high diversity of the overall population, even if asexual expansion is the predominant feature (4). The isolates responsible for infections are serotype A or D, haploid or diploid, and mating type alpha (MATα) or a (5). Single (one strain) or mixed (mixture of isolates belonging to various serotypes, mating types, genotypes, and/or ploidies) infections are possible, as evidenced in unpurified clinical cultures (6). Overall, haploid C. neoformans serotype A MATα isolates represent the most prevalent clinical isolates worldwide (5).

C. neoformans is a facultative intracellular pathogen (7–9). Interaction of C. neoformans with host cells can lead to phagocytosis, with occasional escape to the extracellular space (vomocytosis), and possible transfer of yeast cells between phagocytic cells (10). C. neoformans is capable of replication within the phagolysosome, sometimes associated with host cell lysis (10). These interactions are thought to be involved in different steps of pathogenesis, such as dormancy (11), dissemination (8, 12), and blood-brain barrier crossing (8). Ma and colleagues reported that C. gattii genotype VGII (responsible for the Vancouver Island outbreak) was associated with increased intramacrophagic yeast proliferation and virulence in mice compared to other genotypes (13). For C. neoformans, the influence of genotypic/phenotypic diversity on pathogenesis and clinical outcome has not yet been established.

Our hypothesis is that the clinical outcome of cryptococcal meningoencephalitis in humans is related to fungal determinants and not only to the individual’s immune status and/or genetic susceptibility to infection. We took advantage of a large prospective multicenter study on cryptococcosis (3) that collected clinical information and isolates to test this hypothesis. We thus developed a standardized model of yeast-macrophage (murine cell line J774) interactions to study C. neoformans clinical (ClinCn) isolates and assessed the correlation between the in vitro parameters characterizing the isolates and the outcome of infection in the corresponding patients.

RESULTS

New flow cytometry assays are implemented to assess the dynamics of C. neoformans-macrophage interactions.

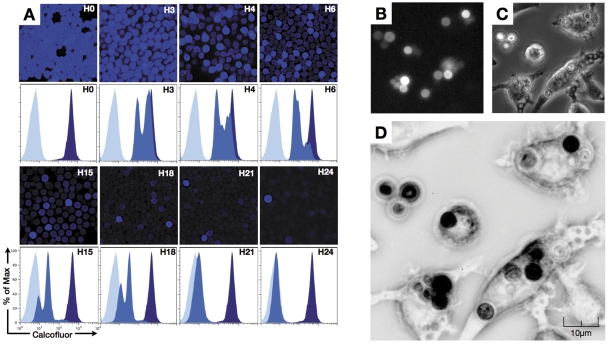

To estimate whether the interaction between ClinCn isolates and host cells was variable, we developed original quantitative flow cytometry assays using the J774 murine macrophage cell line. Calcofluor (Calco) is a basic fluorescent dye used to stain fungal cell wall. Preliminary studies using Calco staining revealed that fluorescence is transmitted from mother to daughter cells during multiplication (Fig. 1A). Immediately after staining, mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was high for all cells. After 3 h of culture, an emerging population with a decreased MFI was detected, while budding cells harboring decreased fluorescence were seen by fluorescence microscopy. This suggested that Calco-labeled chitin was transferred from mother to daughter cells during budding. During protracted incubation, several populations with decreased MFI progressively appeared, while the high-Calco-fluorescent initial population progressively disappeared over 24 h. This phenomenon was confirmed using dynamic imaging of yeast cells proliferating inside J774 cells (Fig. 1B to 1D; see Fig. S1 and Movie S1 in the supplemental material). Of note, macrophages containing yeast cells were capable of mitosis (Fig. S1B and S1C) and subsequent fusion (Fig. S1D and S1E) (14).

FIG 1 .

Decrease in fluorescence in calcofluor-labeled C. neoformans (reference strain H99) during multiplication. (A) C. neoformans multiplication in vitro was evaluated after staining of yeast cells with calcofluor prior to incubation at 30°C in liquid YPD for up to 24 h. Aliquots of the culture were harvested at various times (starting at 0 h of incubation [H0]), and fluorescence was assessed in parallel by microscopic observation and flow cytometry. Decreasing numbers of brightly fluorescent cells were observed from H3 to H24 after incubation, and flow cytometry revealed the appearance of cells of intermediate fluorescence intensity (daughter cells; medium blue) compared to the negative control (light blue) and the initial population (mother cells, dark blue). (B to D) Visualization of H99 multiplication inside macrophages assessed by dynamic imaging. Yeast cells were stained with calcofluor prior to incubation with the J774 cell line at a 2.5:1 ratio in the presence of E1 anticapsular polysaccharide monoclonal antibody (E1 MAb) (106 yeast cells/1 µg E1 MAb). Dynamic imaging using the Nikon Biostation was performed starting after 1 h of coincubation (images obtained at 16 h 45 min are shown). (B) DAPI fluorescence filter. (C) Transmitted light. (D) Decreased fluorescence of daughter cells assessed after image treatment using ImageJ software (merging panels B and C and inverting the look-up table [LUT]. Mother C. neoformans cells appear black, whereas daughter cells look medium to light gray. Original magnification, ×40.

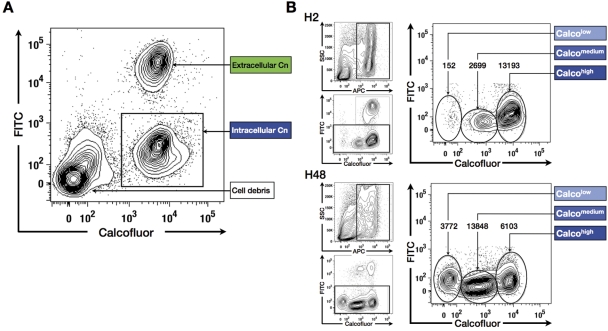

Based on these observations, we decided to assess the dynamics of yeast-macrophage interactions (YMI) by flow cytometry assays (using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter) using the MacsQuant analyzer (FACS-YMI, Fig. 2). Preliminary experiments using the C. neoformans reference strain H99 helped us define optimal opsonin quantity (monoclonal antibody [MAb] E1) and a yeast/macrophage ratio in comparison with microscopic results (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). In the phagocytosis assay, three distinct populations were observed on the Calco-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) dot plot: the intracellular C. neoformans population, which was high for Calco fluorescence and FITC negative (Calcohigh FITCneg); the extracellular C. neoformans population, which was Calcohigh and FITC positive (Calcohigh FITCpos); and cell debris, which was Calconeg FITCneg (Fig. 3A). This allowed us to define a phagocytic index (PI) (103 ±7 for H99). In the proliferation assay, three distinct intracellular C. neoformans populations (allophycocyanin-positive [APCpos] FITCneg gate) were observed: the mother C. neoformans cell population, which was Calcohigh, and two populations of daughter cells that were Calcomedium and Calcolow (Fig. 3B), the cells with the lowest fluorescence being the smallest cells (Fig. S2B). Intracellular proliferation indexes were then calculated based on the number of Calcohigh, Calcomedium, and Calcolow populations after 2 h (IPH2) and 48 h (IPH48) of incubation (1.0 ±0.2 and 1.2 ±0.2, respectively, for H99).

FIG 2 .

Schematic representation of Cryptococcus neoformans (Cn) labeling steps for flow cytometry analysis of yeast-macrophage interaction (FACS-YMI). Yeasts were first stained with calcofluor and then incubated with J774 cells at 37°C in the presence of E1 MAb (opsonin). After careful PBS washings, the incubation was stopped after 2 h of incubation (phagocytosis assay) (A) or prolonged incubation up to 48 h in fresh medium (proliferation assay) (B). In both assays, the remaining extracellular yeast cells were then stained with anti-IgG–FITC antibody and washed, and J774 cells were lysed using H2O. An additional labeling step was performed in the proliferation assay with E1 MAb and anti-IgG–APC added to stain daughter yeast cells. Samples were analyzed using the MacsQuant analyzer.

FIG 3 .

The FACS-YMI allowed assessment of the dynamics of yeast-macrophage interactions. (A) Determination of C. neoformans phagocytosis. Intracellular C. neoformans cells (Calcohigh FITCneg) were easily discriminated from extracellular C. neoformans cells (Calcohigh FITCpos) and macrophage debris (Calconeg FITCneg). (B) Determination of C. neoformans intracellular proliferation. After selection of the APCpos (excluding cell debris, upper left graphs) and FITCneg populations (intracellular C. neoformans, lower left panels), different subsets of intracellular C. neoformans cells corresponding to mother (Calcohigh) and daughter (Calcomedium and Calcolow) C. neoformans cells were observed (right panels). A decrease of mother cells in parallel to an increase in the daughter cell population was observed between 2 h (H2) and 48 h (H48) of coincubation, asserting intracellular proliferation. (The number of events is reported above each subset.)

Results obtained with H99 mutants validate the FACS-YMI assays.

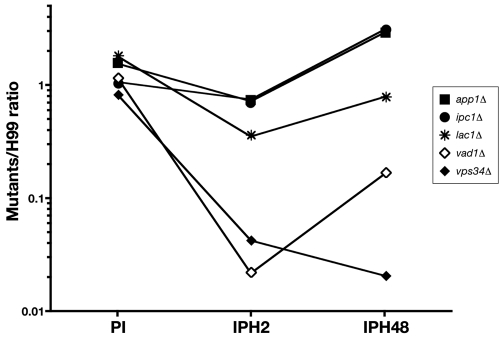

To validate the assays, mutant strains derived from H99 and known for increased phagocytosis (app1Δ and lac1Δ) and decreased proliferation (vad1Δ, vps34Δ, ipc1Δ, and lac1Δ) were screened in comparison to H99. The FACS-YMI assays allowed discrimination between mutant strains based on PI, IPH2, and IPH48 (P < 0.0001 each) (Fig. 4). For the mutants, the PIs were categorized into two groups (similar to H99 [ranging from 0.8 to 1.2] for vps34Δ, ipc1Δ, and vad1Δ or higher [from 1.5 to 1.9] for app1Δ and lac1Δ). Three categories were also delineated for IPH2 (very low [0.02 to 0.04] for vad1Δ and vps34Δ, intermediate low [0.35] for lac1Δ, and low [0.7] for app1Δ and ipc1Δ) and for IPH48 (very low [0.02 to 0.2] for vps34Δ and vad1Δ, low [0.8] for lac1Δ, and high [2.9 to 3.1] for app1Δ and ipc1Δ).

FIG 4 .

Screening of well-characterized mutant strains compared to H99 using the FACS-YMI assay. Dot plots presenting the corresponding values for phagocytosis (PI) and intramacrophagic proliferation at H2 (IPH2) and H48 (IPH48) for each mutant linked by a solid line (log10 scale). PIs were categorized in two groups: similar to H99 (vps34Δ, ipc1Δ, and vad1Δ mutants) and higher than H99 (app1Δ and lac1Δ mutants). Three categories were also delineated for IPH2 (very low for vad1Δ and vps34Δ, intermediate low for lac1Δ, and low for app1Δ and ipc1Δ), and for IPH48 (very low for vps34Δ and vad1Δ, low for lac1Δ, and high for app1Δ and ipc1Δ).

Interactions of C. neoformans clinical isolates with J774 macrophages are highly diverse.

Based on these validated FACS-YMI assays, we then studied 54 ClinCn isolates recovered from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of HIV-positive or -negative unrelated patients (Table 1). An important diversity in terms of genotypes (11 multilocus sequence types) and baseline phenotype characteristics (colony morphology, cell and capsule sizes, growth rate, E1 MAb binding level, chitin content, and urease and laccase activities) was observed (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). We then established the diversity of the ClinCn-macrophage interactions. A 30-fold variation in PI (Fig. 5A; Fig. S4 in the supplemental material), 50-fold variation in IPH2, and 16-fold variation in IPH48 (Fig. 5A; Fig. S5 in the supplemental material) were found. The ClinCn isolates exhibiting high (≥0.5) PI and low (<1.0) E1 MAb binding level were mostly smooth (26/30 [86.7%]), compared to those exhibiting low PI and high E1 binding, which were mostly mucous (9/10 [90%]; P < 0.0001) (Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). There was no significant association between genotypes and baseline phenotypes or phenotypes of ClinCn-macrophage interaction (Fig. S7 in the supplemental material).

TABLE 1 .

Characteristics of the 54 patients corresponding to the 54 clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans studied

| Parameter | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Male/female ratio | 4.4:1 |

| Born in Africa | 12/54 (22.2) |

| HIV infected | 45/54 (83.3) |

| Non-HIV infected | 9/54 (16.7) |

| Abnormal neurology | 24/54 (44.4) |

| Abnormal brain imaging | 18/51 (35.3) |

| Disseminated infection | 35/54 (64.8) |

| Capsular polysaccharide titer of >512 in CSF | 27/49 (55.1) |

| Nonsterilization of CSF at wk 2 | 24/45 (53.3) |

| Death at mo 3 | 11/53 (20.8) |

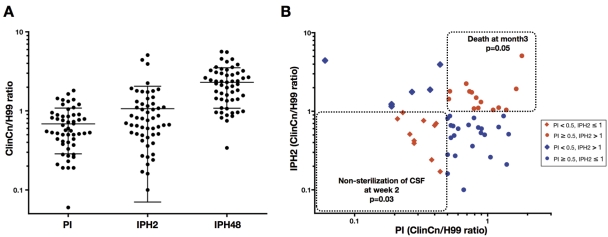

FIG 5 .

The 54 C. neoformans clinical isolates (ClinCn) (serotype A, MATα, haploid) harbored variable interactions with macrophages (phagocytosis and intracellular proliferation). (A) Compared to H99, the distribution of phagocytic (PI), 2-h proliferation (IPH2), and 48-h proliferation (IPH48) indexes showed 30-fold, 50-fold, and 16-fold variations, respectively (log10 scale). Each circle represents the mean of duplicates for a given ClinCn isolate obtained from two independent experiments. Bars represent means ± standard deviations (SD) for the 54 ClinCn isolates. (B) Scatter plots presenting PI versus IPH2. Four categories of isolates were defined according to PI (<0.5 and ≥0.5) and IPH2 (≤1 and >1). The population of isolates harboring a PI of <0.5 and an IPH2 of ≤1 was significantly associated with nonsterilization of CSF at week 2 (P = 0.03), and that harboring a PI of ≥0.5 and an IPH2 of >1 was significantly associated with death at month 3 (P = 0.05).

ClinCn-macrophage interaction phenotypes are associated with variable outcome of cryptococcal meningoencephalitis in humans.

Given the high variability of ClinCn-macrophage interaction phenotypes, we then wondered if these parameters (PI, IPH2, and IPH48) correlated with outcome of infection in the corresponding patients. Four categories of isolates were defined according to PI (<0.5 and ≥0.5) and IPH2 (≤1 and >1). Based on univariate analysis, nonsterilization of CSF despite 2 weeks of antifungal therapy was associated with a population of isolates harboring decreased PI and IPH2 (Fig. 5B; Table 2). The proportions of parameters previously (3) associated with nonsterilization of CSF (gender, dissemination, or high CSF antigen titer) did not significantly differ among the four categories of isolates. Death at months 3 was significantly associated with a population of isolates harboring high PI and IPH2 (Fig. 5B). Parameters previously (3) associated with death at month 3 (abnormal neurology or brain imaging) did not significantly differ among the four categories. In the multivariate analysis, the risk of nonsterilization of the CSF at week 2 was independently associated with low PI and IPH2 (odds ratio [OR], 15.5; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.3 to 184.4; P = 0.030) and with HIV infection (OR, 25.2; 95% CI, 1.8 to 348.6; P = 0.016) (Table 2).

TABLE 2 .

Patients’ outcomes are significantly associated with the phenotypes of interaction with J774 macrophages of the clinical isolates for which the corresponding outcome was availablea

| Outcomea | Parameter | No. (%) of patients with: |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Failure (n = 24) or death (n = 11) |

Success (n = 21) or survival (n = 42) |

OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Yeast eradication from CSF at wk 2 |

PI ≥ 0.5, IPH2 ≤ 1 | 7 (36.8) | 12 (63.2) | Reference | |||||

| PI < 0.5, IPH2 > 1 | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | 6.86 | 0.63–74.19 | 0.113 | 5.79 | 0.53–63.37 | 0.150 | |

| PI ≥ 0.5, IPH2 > 1 | 6 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) | 1.71 | 0.40–7.43 | 0.471 | 3.48 | 0.61–19.78 | 0.159 | |

| PI < 0.5, IPH2 ≤ 1c | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | 6.00 | 0.97–37.30 | 0.055 | 15.51 | 1.30–184.43 | 0.030 | |

| HIV positiveb | 23 (95.8) | 14 (66.7) | 1.64 | 0.85–3.19 | 0.012 | 25.16 | 1.84–348.63 | 0.016 | |

| HIV negative | 1 (4.2) | 7 (33.3) | 0.14 | 0.02–1.16 | |||||

| Death at mo 3 | PI ≥ 0.5, IPH2 ≤ 1 | 3 (13.0) | 20 (87.0) | Reference | |||||

| PI < 0.5, IPH2 > 1 | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | 1.34 | 0.11–15.70 | 0.819 | ||||

| PI ≥ 0.5, IPH2 > 1 | 6 (42.9) | 8 (57.1) | 5 | 1.00–25.02 | 0.050 | ||||

| PI < 0.5, IPH2 ≤ 1 | 1 (10.0) | 9 (90.0) | 0.74 | 0.07–8.13 | 0.806 | ||||

Patients’ outcomes are represented by nonsterilization of CSF at week 2 (i.e., failure or success at yeast eradication from CSF) and death at month 3 (i.e., death or survival).

Only two variables were added to the model due to the small number of events recorded (n = 24).

Parameters appearing in bold are statistically significant.

Expression of some virulence factors correlates with ClinCn-macrophage interaction phenotypes.

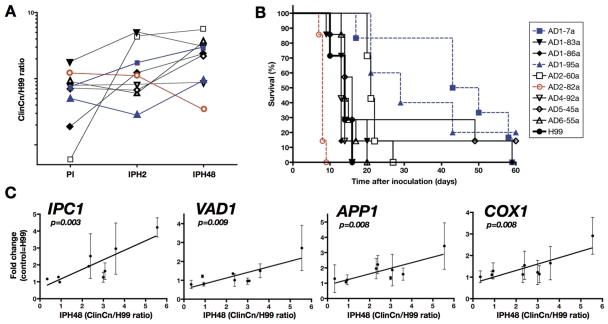

Considering that in a standardized in vitro model, variations in ClinCn-macrophage interaction phenotypes were associated with different outcomes in humans, we further explored known virulence factors in relation to these phenotypes. We selected nine ClinCn isolates (s9-ClinCn) based on various combinations of their ClinCn-macrophage interaction phenotypes (Fig. 6A), genotypes, and related patient outcomes. All s9-ClinCn isolates were fertile (data not shown), with variable virulence in mice, as shown by median survival rates (expressed as a ratio for each s9-ClinCn isolate to H99) ranging from 0.57 (AD2-82a) to 3.3 (AD1-07a) (Fig. 6B; P < 0.0001). The 2-h intracellular (iH2) and baseline (BsH2) relative expressions of six virulence factors (LAC1, URE1, APP1, VAD1, IPC1, and PLB1 genes) (15–20) and one mitochondrial gene (COX1, coding for cytochrome oxidase 1) (13, 21) were quantified with GAPDH (coding for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) as the reference gene and H99 as the control. High BsH2 APP1 expression (>5-fold) was significantly associated with low PI (P = 0.028). IPH48 expression and iH2 expression were significantly correlated for IPC1 (R2 = 0.73, P = 0.003), APP1 (R2 = 0.66, P = 0.008), COX1 (R2 = 0.66, P = 0.008), VAD1 (R2 = 0.65, P = 0.009) (Fig. 6C), and PLB1 (R2 = 0.55, P = 0.021). Levels of PI and iH2 expression of LAC1 (R2 = 0.59, P = 0.016) were also correlated. Hierarchical clustering of iH2 and BsH2 expression levels for the six genes together with PI, IPH2, and IPH48 generated four clusters, confirming the previous correlations (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material). No correlation was found for URE1 gene expression.

FIG 6 .

The in vivo behavior (virulence in mice) of the s9-ClinCn isolates is heterogeneous and the intracellular (J774 cells) expression levels of known virulence factors correlate with the 48-h proliferation index. (A) Dot plots presenting the corresponding PI, IPH2, and IPH48 values for each of the s9-ClinCn isolates. The values corresponding to a given isolate are linked by a solid line (log10 scale). (B) Outbred male mice were intravenously inoculated with 105 yeast cells, and death was recorded over 60 days. Compared to H99 (black circle, thick line), AD2-82a (open red circle, red dotted line) is more virulent (median survival ratio of 0.57), whereas AD1-95a (blue triangle, blue dotted line) and AD1-7a (blue square, blue dotted line) are less virulent (median survival ratios of 2.1 and 3.3, respectively). (C) Compared to H99, IPH48 of the s9-ClinCn isolates correlated with the intracellular expression of the IPC1, VAD1, APP1, and COX1 genes. Bars represent means ± standard deviations (SD) of duplicates from 2 independent experiments for each s9-ClinCn isolate. The linear regression curve is shown.

DISCUSSION

In order to assess the correlation between C. neoformans-macrophage interactions and clinical parameters, we designed new standardized assays. Since C. neoformans strains have been shown to behave similarly in various host cells (murine and human macrophages or amoeba) (22–24), we chose J774 cells for the assays. The use of this cell line and flow cytometry allowed quantification of large samples (more than 106 yeast cells and 105 macrophages) and accurate discrimination of intra- versus extracellular and mother versus daughter yeast cells. The FACS-YMI assays were based on Calco staining and its ability to be sparsely transmitted to daughter cells during budding. Indeed, bud formation in basidiomycetous yeasts is enteroblastic (25). The inner layer of the parental multilamellar cell wall is in direct continuation with the outer layer of the bud (26). Given that chitin (~9% of the cell wall) is distributed throughout the cell wall (27, 28), the Calco-labeled chitin of the mother cell wall could contribute to the fluorescence of the daughter cells. The FACS-YMI assays represent a promising alternative to current studies dealing with microscopic or colony-forming unit enumeration and have potential wide applications. The FACS-YMI assay could become, like the carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) assay in immunology (29), an easy and reliable test to study dynamics of fungal cell proliferation.

Up to now, C. neoformans-host cell interactions have mostly been studied using reference or mutant strains. Few reports discuss the variability of C. neoformans clinical isolates (30), and only a few dealt with parasites (31–34) and other fungal species (13, 35), and none have analyzed correlation with clinical outcome. Using a large collection of ClinCn isolates, we uncovered highly variable phenotypes of C. neoformans-macrophage interaction without correlation with genotypes, in contrast with what was demonstrated for the clonal hypervirulent VGII C. gattii isolates (13). This could be explained by differences in the pathophysiology of infections due to C. gattii and C. neoformans, the first being more frequently responsible for primary infection rather than reactivation, in contrast to C. neoformans-related diseases (36). As a consequence, the virulence of these two pathogenic fungi in humans could be different in terms of host adaptation and immunological escape mechanisms. One may also wonder if the phenotypic intraspecies diversity reported for eukaryotes, as opposed to prokaryotes, could be explained by their complex genomes and potential recombination events during mating. This is especially true for C. neoformans, known for its complex sexual reproduction (4).

Since yeast-macrophage interactions are involved in the pathogenesis, we assessed whether the phenotypes determined in vitro were associated with a specific outcome in humans. We found that isolates harboring low PI and low IPH2 were significantly associated with nonsterilization of CSF at weeks 2, whereas those harboring high PI and high IPH2 were associated with death at month 3. Our results suggest that fungal determinants are involved, as are host factors (genetic background and type of immunosuppression) in the outcome of cryptococcal meningoencephalitis. These results highlight the monocyte/macrophage lineage as a major key player in the pathophysiology of the infection in humans, as already suggested by studies on blood-brain barrier crossing and dissemination in mice (8, 37, 38). Additional experiments are needed to assess the relevance of these data in different clinical settings, such as infections with other serotypes, mixed infections, and extrameningeal cryptococcosis.

The fate of C. neoformans cells in contact with host cells is dependent on multiple and yet partially unknown factors. The first one is phagocytosis. Unexpectedly, E1 binding level inversely correlated with PI. This suggests that, in addition to Fcγ and complement receptors (39), other receptors involved in innate immunity, such as mannose receptors, CD14, and Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) (40), or factors modulating phagocytosis, such as the secreted protein App1p (20), the pleiotropic transcription factor Gat201p, or the Gat201-bound gene product Gat204p (41), play a role in the phagocytosis process. After phagocytosis, C. neoformans intracellular persistence and proliferation are key steps of the pathogenesis process. We found a relationship between intramacrophagic COX1, as shown in C. gattii (13), but also IPC1, VAD1, APP1, and PLB1 gene expression and ClinCn intracellular proliferation. This validates the FACS-YMI assays as innovative means to study virulence factors and potentially decipher the mechanisms by which C. neoformans cells escape or survive phagocytosis. Dissociation between early (IPH2) and late (IPH48) intracellular proliferation indexes was observed for some ClinCn isolates as well as for the lac1Δ mutant. We also found that a variable proportion of the intracellular yeast cells were still Calcohigh after 48 h of incubation, suggesting that they could either be dead or in a low replicative stage or dormancy. Altogether, this suggests that adaptation inside macrophage occurs. Some strains may have “ready-made” virulence (42) (high IPH2 and high IPH48), whereas, for others (low IPH2 and high IPH48), a longer period of metabolic adaptation to hypoxia or starvation inside macrophages could be needed to express virulence factors as described in vivo (43). Overall, these various phenotypes could reflect different patterns of pathogenicity. Given the complex biological processes that lead to survival or multiplication inside the phagolysosome, other studies are needed to decipher the precise mechanisms and molecular events involved.

In conclusion, while many studies established that host susceptibility to infection is crucial and that virulence factors of the pathogens can be differentially expressed as a function of environmental conditions (medium, intracellular versus free yeasts, etc.), our study demonstrates that, under the same experimental conditions, clinical isolates of C. neoformans behaved differently, a diversity that could participate in the variable outcome of meningoencephalitis in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell line.

The J774.16 cell line (hereafter J774) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) to study the interaction of C. neoformans clinical isolates with macrophages. J774 is a murine macrophage-like cell line derived from a reticulum sarcoma. Cells were maintained at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (fresh medium) (all from Invitrogen). Cells were used between 10 and 35 passages.

C. neoformans strains.

A panel of 54 C. neoformans clinical isolates was selected. All isolates were recovered from cerebrospinal fluids and responsible for single infections (one isolate/one genotype/one infection), as opposed to mixed infections (6). All isolates were collected during the CryptoA/D prospective study (3). This study was approved and reported to the French Ministry of Health (registration no. DGS970089). For each isolate, the patient’s background, clinical presentation, outcome of infection, and various biological parameters were available (Table 1). Single colonies (ClinCn) from each clinical isolate were frozen in 40% glycerol at −80°C and used thereafter. All ClinCn isolates were characterized as haploid, serotype A, MATα using previously described methods (6). Before each experiment, yeasts were first cultured on Sabouraud agar (SA) medium and then subcultured in liquid yeast extract-peptone-glucose medium (YPD) at 30°C at 150 rpm for 22 h (standard YPD culture). All isolates were tested blind to the clinical parameters.

Mutant strains (all derived from H99) with the genotypes lac1Δ (lacking laccase 1 [Lac1p]) (44), vps34Δ (lacking the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase [PI3-kinase] Vps34p) (45), vad1Δ (lacking the DEAD-box RNA helicase Vad1p) (18) (kindly donated by P. Williamson, NIH, Bethesda, MD), app1Δ (lacking the antiphagocytic protein App1p [20], which binds the CR3 and CR2 receptors on phagocytic cells) (46), and ipc1Δ (in which inositol-phosphoryl ceramide synthase, Ipc1p, is downregulated) (19) (kindly donated by M. Del Poeta, Charleston, SC), were also used. Strain H99 (serotype A, MATα, haploid) (kindly donated by J. Heitman, Duke University, NC) was used as the reference strain in all experiments.

Reagents and C. neoformans labeling.

Calcofluor white dye (Calco) (fluorescent brightener 28; Sigma) specifically stains chitin contained in the cell wall of some eukaryote microorganisms and was used to label C. neoformans. Yeast cells were collected from standard YPD culture, washed twice, and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Invitrogen) at 5 × 106 to 2 × 107/ml. The cells were then incubated with Calco at 10 µg/ml in PBS for 10 min in the dark at room temperature and then washed twice in PBS. In preliminary experiments, we checked that the in vitro growth curves of strains were similar (identical slopes) for Calco-stained and unstained C. neoformans strains, except for the lac1Δ mutant, for which growth decreased after Calco staining (data not shown). To assess the evolution of Calco fluorescence during multiplication, Calco-stained C. neoformans cells (106/ml) cultured in standard YPD were analyzed using fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss Axioscope A1 with a 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole [DAPI] filter) and flow cytometry at various incubation times. E1, a murine IgG1 monoclonal anticapsular polysaccharide antibody (E1 MAb) was used as an opsonin (47). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled horse anti-mouse IgG (anti-IgG–FITC) (Vector Laboratories) and allophycocyanin-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (anti-IgG–APC) (BD Pharmingen) were used at 1:100 for a 20-min incubation.

Baseline genotypes and phenotypes characterization of the ClinCn isolates.

The genotype of each ClinCn isolate was determined by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) of seven loci, as previously described (48). The morphological aspect (smooth or mucous) was assessed after 72 h of culture on SA at 30°C. Growth curves were determined in 96-well plates starting at 106/ml without agitation in liquid YPD at 30°C (triplicate wells). The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was recorded up to 140 h of incubation (Labsystems Multiskan). The regression line (y = ax + b) was determined, and the results were expressed as the ratio between the slopes (“a” value) for the ClinCn isolates compared to that for H99. Cell and capsule sizes were determined after standard YPD culture. Cell suspensions were made at 106/ml in PBS. An aliquot was observed in India ink suspension, using an Axioscan microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany) and the AxioCam ICc1 camera (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Cell size, delineated by the cell wall, and capsulated cell size, delineated by the white exclusion zone around the cells, were measured for 10 cells randomly selected from each ClinCn isolate and H99 using the Zeiss AxioVision software (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Results were expressed as the average size ratio for ClinCn versus H99 cells. The binding of E1 MAb to the capsule surface was determined. Yeast cells were cultured on SA for 24 h at 30°C for each ClinCn isolate, washed in PBS, and suspended at a concentration equivalent to an OD600 of 0.1. Then, 300 µl of the suspension was centrifuged and pellets were resuspended in 100 µl of PBS containing E1 MAb (0.5 µg/ml) and FITC-labeled anti-IgG for 20 min in the dark at room temperature. Then, 400 µl of PBS–1% paraformaldehyde (PFA) was added to fix cells before cytometry analysis. The results were expressed as the ratio between the geometric mean of the FITC fluorescence intensity for the ClinCn isolates and H99. The chitin content was determined after standard YPD culture and standard calcofluor staining by quantification of the geometric mean of the calcofluor fluorescence intensity for the ClinCn isolates and H99 using flow cytometry (see below).

To study the variability of the s9-ClinCn, urease and laccase activities were quantified using urea agar base medium (49) and asparagine agar containing 1 mM l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (l-Dopa) (50). Urease and laccase activities of 105 to 107 C. neoformans cells after 24 h of incubation at 37°C and 72 h of culture at 30°C, respectively, were quantified by measuring the diameter of the pink halo (urease), and the RGB content of colonies (laccase), using ImageJ software. The mating assay used Murashige and Skoog medium (51), and fertility was assessed after 7 days of incubation at room temperature in the dark with KN99a (serotype A, mating type a), KN99α (serotype A, mating type α), and JEC20 (serotype D, mating type a).

Interaction with macrophages.

J774 cell suspensions (105 in fresh medium per well of a 24-well culture plate) were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 48 h. The day of the experiment, E1 MAb (250 µl) and Calco-stained C. neoformans suspension (250 µl), both in fresh medium at the desired concentrations, were added to the J774 cell monolayer and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 2 h (phagocytosis assay, C. neoformans/J774 ratio, 5:1). Nonadherent extracellular yeast cells were then removed by PBS washings, and incubation was stopped to assess phagocytosis or extended to determine intracellular proliferation. Phagocytosis was determined after staining residual extracellular yeasts using anti-IgG–FITC, additional PBS washings, and macrophage lysis with distilled water (Fig. 2A). The samples were then centrifuged, resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS (PFA-PBS), vortexed, and sonicated for 3 min before analysis.

To assess intracellular proliferation of ClinCn using flow cytometry (proliferation assay, C. neoformans/J774 ratio, 2.5:1), the incubation was protracted in fresh medium for 48 h. Residual extracellular yeast cells were stained by addition of E1 MAb (0.5 µg/ml) and anti-IgG–FITC and washed in PBS, and J774 cells were lysed by water (Fig. 2B). In order to differentiate potentially unstained C. neoformans cells from cell debris, an additional step was done using E1 MAb and APC–anti-IgG. All yeast cells were APCpos, while only extracellular yeast cells were APCpos FITCpos.

Intracellular proliferation was determined for each ClinCn isolate at the end of the phagocytosis step (H2) and at 48 h (H48). Phagocytosis and proliferation were analyzed in two independent experiments.

Flow cytometry analysis of yeast-macrophage interaction (FACS-YMI).

Flow cytometry analyses were performed using MacsQuant analyzer and MacsQuantify software 2.0 (Milteniy BioTeC) to provide absolute quantification. Samples were analyzed using FlowJo 8.7 software (Tree Star, Inc.). Aggregates were excluded by gating relevant events in the forward scatter/side scatter (FSC/SSC) contour plot. Three parameters were calculated: (i) the phagocytic index (PI) as the number of events in the Calcohigh FITCneg gate at H2, (ii) intracellular proliferation at H2 (IPH2) as the ratio between daughter cells (Calcolow + Calcomedium) and mother cells (Calcohigh) at H2, and (iii) intracellular proliferation at H48 (IPH48) as the ratio between daughter cells (Calcolow + Calcomedium) at H48 and mother cells (Calcohigh) at H2.

Results were expressed as the ratio of the given parameter for the ClinCn/mutant strains compared to the H99 parameter determined in the same run. We assessed that results obtained during the two independent experiments were reproducible for PI, IPH2, and IPH48 (P < 0.0001 for each parameter), and means of replicates were then used for subsequent analyses.

Dynamic imaging.

The evolution of fluorescence intensity from mother to daughter intracellular yeasts was assessed by dynamic imaging (Nikon Biostation). J774 cells were cultured and incubated with Calco-stained C. neoformans cells (2.5:1) in dishes (Hi-Q4 35-mm diameter; Nikon) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Series of images were taken by phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy (DAPI filter) every 5 min for 24 h at ×40 magnification. Merging and inverting the look-up table (LUT) were done using ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). The movie was generated from the 289 modified pictures using iMovie software v8.0.6 (Apple, Inc.).

Virulence in mice.

Outbred OF1 male mice (ages 6 to 8 weeks) (Charles Rivers Laboratories) were housed 7 per cage in our animal facilities and received food and water ad libitum. The inoculum was prepared in sterile saline from standard YPD culture. The C. neoformans cell suspension (105/mouse) was inoculated intravenously into 7 mice. Survival was recorded once daily until day 60 after inoculation. Animals about to die (unable to reach their food) were systematically euthanized by CO2 inhalation. Animal studies were approved by the Institut Pasteur Animal Care Committee (03/144).

Real-time PCR.

RNA extraction was performed on the s9-ClinCn isolates and H99 cells coincubated with J774 cells (intracellular condition [iH2]) or in fresh medium (baseline condition [BsH2]) for 2 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. For iH2, J774 cells were washed twice with PBS, scraped, lysed in 2 ml 0.05% SDS–ice-cold water, and vortexed, and the pellet was collected after 3 min of centrifugation at 2,000 relative centrifugal force (RCF). RTL lysis buffer (500 µl; Qiagen) and 1:100 β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma) were added to the C. neoformans pellets. The suspensions were transferred to Ceramique Magna Lyser green bead tubes (Roche Diagnostics), homogenized three times with the Magna Lyser instrument (30 s at 7,000 rpm), and centrifuged (3 min at 10,000 RCF). RNA extraction was performed on 350 µl supernatant using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). RNAs were quantified and qualified using the Nanodrop spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Inc.).

cDNA was generated from Turbo DNase (Ambion)-treated RNA using the Transcriptor first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Roche Diagnostics). Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) using 10 µl of LightCycler 480 SYBR green I master, 2 µl of cDNA, and specific primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) in a LightCycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics) consisted of a denaturation step at 95°C, 45 cycles of amplification (95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 5 s, and 72°C for 5 s). Each cDNA was analyzed in duplicate and normalized with the corresponding GAPDH gene expression (52) and was variable in different experimental conditions. Fold changes for each s9-ClinCn isolate (iH2 and BsH2 conditions) were assessed compared to H99 under the same conditions, according to Pfaffl (53). Two independent RNA extractions for each condition were analyzed blindly, and an internal calibrator consisting of an iH2 cDNA of H99 was used in each RT-PCR run as recommended (54).

Statistical analysis.

Graph and Pearson’s index (R2) calculation, exact Fisher’s test, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed using Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software). Stata 10.0 software (Stata Corporation) was used to compare the ClinCn-macrophage interaction phenotypes with clinical outcome for the corresponding patients. For the multivariate analysis, logistic regression was used to determine factors independently associated with nonsterilization of CSF at week 2 (45 patients with available information). Only two variables were entered in the model because of the limited number of events (n = 24). Odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were determined.

Schematic representation of fold changes was performed using the open-source genomic analysis software MeV v4.6.1 (The TM4 Development Group) obtained from http://mev.tm4.org (55). Complete linkage clustering and Pearson’s correlation were chosen to perform hierarchical clustering. The principal component analysis (PCA) was performed based on three interaction parameters (PI, IPH2, and IPH48) and five mycological parameters (cell and capsule size, E1 binding, growth, and chitin content) using MeV v4.6.1 (Manhattan distance, mean centering mode, and 10 neighbors for KNN imputation). Variables were compared using the Student t test. P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Intracellular proliferation of calcofluor-labeled H99 C. neoformans-generated daughter cells with low calcofluor fluorescence. Macrophage mitosis with repartition of the intracellular C. neoformans pool in the daughter macrophage cells and fusion of C. neoformans-containing macrophage daughter cells were observed concomitantly. Significant images were selected from the movie, 1 h (A), 5 h 30 min (B), 6 h 05 min (C), 6 h 35 min (D), 6 h 45 min (E), 12 h (F), 16 h (G), 20 h (H), and 24 h (I) after the beginning of image acquisitions. Dark blue arrows, mother C. neoformans cells; light blue arrows, daughter C. neoformans cells; white arrows, mitosis of C. neoformans-containing macrophages; red arrows, repartition of C. neoformans cells in the two separated macrophage cells after mitosis; yellow arrows: fusion of the previously separated macrophage cells. Download Figure S1, PDF file, 0.943 MB.

Preliminary experiments. (A) Influence of the C. neoformans/macrophage ratio and of the quantity of E1 MAb on the magnitude of C. neoformans strain H99 phagocytosis by murine macrophage cell line J774. The concentration of macrophages was kept constant, while that of H99 varied to provide a ratio ranging from 1:1 to 10:1. The anti-capsular polysaccharide E1 MAb was added at 0.1, 1, or 10 µg/well. The optical phagocytic index (Opt-PI) was calculated as the number of intracellular yeast cells/100 macrophages. Each condition was tested in duplicate in two independent experiments. Optimal conditions for the phagocytosis and the proliferation assays are shown. The bars represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of one representative experiment. (B) During intracellular proliferation of H99 C. neoformans cells, the size of each cell using forward scatter (FSC) histograms (right panel) is lower in the daughter cell populations (Calcolow and Calcomedium) than in the mother cells (Calcohigh) at 2 h of coincubation (H2) and H48. Download Figure S2, PDF file, 0.881 MB.

The baseline phenotype of the ClinCn isolates is diverse in terms of enzymatic activity and cell characteristics. (A) Distribution of cell sizes, capsule sizes, growth rates (slope), E1 MAb binding level, and chitin content compared to those of the H99 reference strain. Horizontal lines represent means ± standard deviation (SD). (B) Variability of urease activity in the s9-ClinCn (105 to 107 cells) expressed as the diameter of the red circle around the colony (ImageJ software v1.42q). (C) Variability of laccase activity in the s9-ClinCn isolates (105 to 107 cells) as shown by the intensity of the brown pigment. Download Figure S3, PDF file, 0.866 MB.

Phagocytosis assay. Contrasted phagocytic indexes for two ClinCn isolates compared to H99 assessed by FACS-YMI (left panel) and fluorescence microscopy (right panel). The number of Calcohigh FITCneg events (intracellular yeasts) is reported above the gates. Blue-fluorescent C. neoformans cells are intracellular, whereas blue and green fluorescent C. neoformans cells are extracellular (right panel). Download Figure S4, PDF file, 0.844 MB.

Proliferation assay. Contrasted proliferation indexes (IPH2 and IPH48) for two ClinCn isolates compared to H99 assessed using FACS-YMI at 2 h (H2), 24 h (H24), and 48 h (H48) of coincubation. The proportion of Calcohigh, Calcomedium, and Calcolow events in the APCpos and FITCneg gates is reported above each gate. Download Figure S5, PDF file, 0.903 MB.

The E1 MAb binding level is inversely correlated with PI. Shown is a scatter plot of PI versus the E1 MAb binding level for the 54 ClinCn isolates compared to H99 according to colony morphology recorded as mucous (open circle) or smooth (black circle). The solid line represents the regression line (P = 0.006). Dotted lines show the cutoff values for PI and E1 MAb binding, delineating a significant association with colony morphology (P < 0.0001). Download Figure S6, PDF file, 0.792 MB.

The phenotype of the 54 ClinCn isolates is unrelated to their MLST genotype. Principal component analysis (PCA) analysis was performed based on three interaction parameters (PI, IPH2, and IPH48) and eight mycological parameters (cell and capsule sizes, E1 MAb binding, growth, and chitin content) using MeV software v4.6.1 (Manhattan distance, mean centering mode, and 10 neighbors for KNN imputation). The repartition of each plot upon each axis is reported in the right panel. Each color represents one genotype (n = 11). Download Figure S7, PDF file, 0.807 MB.

Hierarchical clustering analysis of expression of six virulence genes under basal (BsH2) and 2-h intracellular (iH2) conditions in addition to the ClinCn/H99 ratio for PI, IPH2, and IPH48. Pearson correlation and complete linkage analysis generated four clusters together with macrophage interaction parameters. The iH2 expression of IPC1, VAD1, APP1, PLB1, and COX1 clustered with IPH48 (cluster 4), while LAC1 iH2 expression clustered with IPH2 (cluster 2), and all BsH2 gene expression levels clustered together (cluster 3), except LAC1 BsH2 expression, which clustered with PI (cluster 1). Download Figure S8, PDF file, 0.830 MB.

Primers and PCR conditions used to assess relative quantification of known virulence genes in this study

Dynamic imaging of calcofluor-labeled H99 C. neoformans cell-macrophage interactions using the Nikon Biostation IM. The movie began 1 h after coincubation between opsonized C. neoformans cells and J774 macrophages. An image was taken every 5 min for 24 h at ×40 magnification using transmitted light and fluorescence microscopy (DAPI filter). Dark blue arrows, mother C. neoformans cells; light blue arrows, daughter C. neoformans cells; white arrows, mitosis of C. neoformans-containing macrophages; red arrows, repartition of C. neoformans cells in the two separated macrophage cells after mitosis; yellow arrows, fusion of the previously separated macrophage cells. Download Movie S1, MOV file, 6.458 MB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Frederique Vernel-Pauillac and Dea Garcia-Hermoso (Molecular Mycology Unit) for the experimental infections, Emmanuel Perret (Imagopole) for expertise in dynamic imaging, and Laure Diancourt (Genotyping and Public Health Facility) for the MLST.

A.A. is a recipient of a “Poste d’Accueil CNRS-CEA/APHP.” This work was supported by Institut Pasteur. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Citation Alanio A, Desnos-Ollivier M, Dromer F. 2011. Dynamics of Cryptococcus neoformans-macrophage interactions reveal that fungal background influences outcome during cryptococcal meningoencephalitis in humans. mBio 2(4):e00158-11. doi:10.1128/mBio.00158-11.

REFERENCES

- 1. Park BJ, et al. 2009. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS 23:525–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Casadevall A, Perfect J. 1998. Cryptococcus neoformans, p. 407–456 ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dromer F, Mathoulin-Pélissier S, Launay O, Lortholary O, Cryptococcosis Study Group French. 2007. Determinants of disease presentation and outcome during cryptococcosis: the CryptoA/D study. Plos Med 4:e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hsueh Y, Lin X, Kwon-Chung K, Heitman J. 2010. Sexual reproduction of Cryptococcus, p. 81–96 In Heitman J, Kozel TR, Kwon-Chung KJ, Perfect JR, Casadevall A, Cryptococcus: from human pathogen to model yeast. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lin X, Heitman J. 2006. The biology of the Cryptococcus neoformans species complex. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60:69–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Desnos-Ollivier M, et al. 2010. Mixed infections and in vivo evolution in the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. mBio 1(1):e00091-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feldmesser M, Kress Y, Novikoff P, Casadevall A. 2000. Cryptococcus neoformans is a facultative intracellular pathogen in murine pulmonary infection. Infect. Immun. 68:4225–4237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Charlier C, et al. 2009. Evidence of a role for monocytes in dissemination and brain invasion by Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 77:120–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chrétien F, et al. 2002. Pathogenesis of cerebral Cryptococcus neoformans infection after fungemia. J. Infect. Dis. 186:522–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bliska JB, Casadevall A. 2009. Intracellular pathogenic bacteria and fungi—a case of convergent evolution? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:165–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Del Poeta M. 2004. Role of phagocytosis in the virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell 3:1067–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Santangelo R, et al. 2004. Role of extracellular phospholipases and mononuclear phagocytes in dissemination of cryptococcosis in a murine model. Infect. Immun. 72:2229–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ma H, et al. 2009. The fatal fungal outbreak on Vancouver Island is characterized by enhanced intracellular parasitism driven by mitochondrial regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:12980–12985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luo Y, Alvarez M, Xia L, Casadevall A. 2008. The outcome of phagocytic cell division with infectious cargo depends on single phagosome formation. PLoS One 3:e3219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cox GM, et al. 2001. Extracellular phospholipase activity is a virulence factor for Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 39:166–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cox GM, Mukherjee J, Cole GT, Casadevall A, Perfect JR. 2000. Urease as a virulence factor in experimental cryptococcosis. Infect. Immun. 68:443–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Williamson PR. 1997. Laccase and melanin in the pathogenesis of Cryptococcus neoformans. Front. Biosci. 2:e99–e107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Panepinto J, et al. 2005. The DEAD-box RNA helicase Vad1 regulates multiple virulence-associated genes in Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Clin. Invest. 115:632–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Luberto C, et al. 2001. Roles for inositol-phosphoryl ceramide synthase 1 (IPC1) in pathogenesis of C. neoformans. Genes Dev. 15:201–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Luberto C, et al. 2003. Identification of App1 as a regulator of phagocytosis and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Clin. Invest. 112:1080–1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Toffaletti DL, Del Poeta M, Rude TH, Dietrich F, Perfect JR. 2003. Regulation of cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COX1) expression in Cryptococcus neoformans by temperature and host environment. Microbiology 149:1041–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Steenbergen JN, Shuman HA, Casadevall A. 2001. Cryptococcus neoformans interactions with amoebae suggest an explanation for its virulence and intracellular pathogenic strategy in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:15245–15250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chrisman CJ, Alvarez M, Casadevall A. 2010. Phagocytosis of Cryptococcus neoformans by, and nonlytic exocytosis from, Acanthamoeba castellanii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:6056–6062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fries BC, Taborda CP, Serfass E, Casadevall A. 2001. Phenotypic switching of Cryptococcus neoformans occurs in vivo and influences the outcome of infection. J. Clin. Invest. 108:1639–1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moore R. 1998Cytology and ultrastructure of yeasts and yeastlike fungi, p. 33–44 In Kurtzman CP, Fell JW, The yeasts, a taxonomic study. Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cassone A, Simonetti N, Strippoli V. 1974. Wall structure and bud formation in Cryptococcus neoformans. Arch. Microbiol. 95:205–212 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Simmons R. 1989. Comparison of chitin localization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Cryptococcus neoformans and Malassezia spp. Mycol. Res. 94:551–553 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gilbert N, Lodge J, Specht C. 2010. The cell wall of Cryptococcus, p. 67–80 In Heitman J, Kozel TR, Kwon-Chung KJ, Perfect JR, Casadevall A,Cryptococcus: from human pathogen to model yeast. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lyons AB, Parish CR. 1994. Determination of lymphocyte division by flow cytometry. J. Immunol. Methods 171:131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kozel TR, Pfrommer GS, Guerlain AS, Highison BA, Highison GJ. 1988. Strain variation in phagocytosis of Cryptococcus neoformans: dissociation of susceptibility to phagocytosis from activation and binding of opsonic fragments of C3. Infect. Immun. 56:2794–2800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rosowski EE, et al. 2011. Strain-specific activation of the NF-kappaB pathway by GRA15, a novel Toxoplasma gondii dense granule protein. J. Exp. Med. 208:195–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kébaïer C, Louzir H, Chenik M, Ben Salah A, Dellagi K. 2001. Heterogeneity of wild Leishmania major isolates in experimental murine pathogenicity and specific immune response. Infect. Immun. 69:4906–4915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Holzmuller P, et al. 2008. Virulence and pathogenicity patterns of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense field isolates in experimentally infected mouse: differences in host immune response modulation by secretome and proteomics. Microbes Infect. 10:79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lobo C-A, et al. 2004. Invasion profiles of Brazilian field isolates of Plasmodium falciparum: phenotypic and genotypic analyses. Infect. Immun. 72:5886–5891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. MacCallum DM, et al. 2009. Property differences among the four major Candida albicans strain clades. Eukaryot. Cell 8:373–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dromer F, Casadevall A, Perfect J, Sorrell T. 2010. Cryptococcus neoformans: latency and disease, p. 429–430 In Heitman J, Kozel TR, Kwon-Chung KJ, Perfect JR, Casadevall A,Cryptococcus: from human pathogen to model yeast. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shi M, et al. 2010. Real-time imaging of trapping and urease-dependent transmigration of Cryptococcus neoformans in mouse brain. J. Clin. Invest. 120:1683–1693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Casadevall A. 2010. Cryptococci at the brain gate: break and enter or use a Trojan horse? J. Clin. Invest. 120:1389–1392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Macura N, Zhang T, Casadevall A. 2007. Dependence of macrophage phagocytic efficacy on antibody concentration. Infect. Immun. 75:1904–1915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Levitz SM. 2010. Innate recognition of fungal cell walls. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chun CD, Brown JCS, Madhani HD. 2011. A major role for capsule-independent phagocytosis-inhibitory mechanisms in mammalian infection by Cryptococcus neoformans. Cell Host Microbe 9:243–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Casadevall A, Steenbergen JN, Nosanchuk JD. 2003. “Ready made” virulence and “dual use” virulence factors in pathogenic environmental fungi—the Cryptococcus neoformans paradigm. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:332–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hu G, Cheng P-Y, Sham A, Perfect JR, Kronstad JW. 2008. Metabolic adaptation in Cryptococcus neoformans during early murine pulmonary infection. Mol. Microbiol. 69:1456–1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu X, Hu G, Panepinto J, Williamson PR. 2006. Role of a VPS41 homologue in starvation response, intracellular survival and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 61:1132–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hu G, et al. 2008. PI3K signaling of autophagy is required for starvation tolerance and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Clin. Invest. 118:1186–1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stano P, et al. 2009. App1: an antiphagocytic protein that binds to complement receptors 3 and 2. J. Immunol. 182:84–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dromer F, Salamero J, Contrepois A, Carbon C, Yeni P. 1987. Production, characterization, and antibody specificity of a mouse monoclonal antibody reactive with Cryptococcus neoformans capsular polysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 55:742–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Meyer W, et al. 2009. Consensus multi-locus sequence typing scheme for Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. Med. Mycol. 47:561–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kwon-Chung K, Bennett J. 1992. Medical mycology, p. 816–826 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fan W, Kraus PR, Boily M-J, Heitman J. 2005. Cryptococcus neoformans gene expression during murine macrophage infection. Eukaryot. Cell 4:1420–1433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Xue C, Tada Y, Dong X, Heitman J. 2007. The human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus can complete its sexual cycle during a pathogenic association with plants. Cell Host Microbe 1:263–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Xue C, et al. 2010. Role of an expanded inositol transporter repertoire in Cryptococcus neoformans sexual reproduction and virulence. mBio 1(1):e00084-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pfaffl MW. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hellemans J, Mortier G, de Paepe A, Speleman F, Vandesompele J. 2007. qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative PCR data. Genome Biol. 8:R19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Saeed AI, et al. 2003. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques 34:374–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Intracellular proliferation of calcofluor-labeled H99 C. neoformans-generated daughter cells with low calcofluor fluorescence. Macrophage mitosis with repartition of the intracellular C. neoformans pool in the daughter macrophage cells and fusion of C. neoformans-containing macrophage daughter cells were observed concomitantly. Significant images were selected from the movie, 1 h (A), 5 h 30 min (B), 6 h 05 min (C), 6 h 35 min (D), 6 h 45 min (E), 12 h (F), 16 h (G), 20 h (H), and 24 h (I) after the beginning of image acquisitions. Dark blue arrows, mother C. neoformans cells; light blue arrows, daughter C. neoformans cells; white arrows, mitosis of C. neoformans-containing macrophages; red arrows, repartition of C. neoformans cells in the two separated macrophage cells after mitosis; yellow arrows: fusion of the previously separated macrophage cells. Download Figure S1, PDF file, 0.943 MB.

Preliminary experiments. (A) Influence of the C. neoformans/macrophage ratio and of the quantity of E1 MAb on the magnitude of C. neoformans strain H99 phagocytosis by murine macrophage cell line J774. The concentration of macrophages was kept constant, while that of H99 varied to provide a ratio ranging from 1:1 to 10:1. The anti-capsular polysaccharide E1 MAb was added at 0.1, 1, or 10 µg/well. The optical phagocytic index (Opt-PI) was calculated as the number of intracellular yeast cells/100 macrophages. Each condition was tested in duplicate in two independent experiments. Optimal conditions for the phagocytosis and the proliferation assays are shown. The bars represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of one representative experiment. (B) During intracellular proliferation of H99 C. neoformans cells, the size of each cell using forward scatter (FSC) histograms (right panel) is lower in the daughter cell populations (Calcolow and Calcomedium) than in the mother cells (Calcohigh) at 2 h of coincubation (H2) and H48. Download Figure S2, PDF file, 0.881 MB.

The baseline phenotype of the ClinCn isolates is diverse in terms of enzymatic activity and cell characteristics. (A) Distribution of cell sizes, capsule sizes, growth rates (slope), E1 MAb binding level, and chitin content compared to those of the H99 reference strain. Horizontal lines represent means ± standard deviation (SD). (B) Variability of urease activity in the s9-ClinCn (105 to 107 cells) expressed as the diameter of the red circle around the colony (ImageJ software v1.42q). (C) Variability of laccase activity in the s9-ClinCn isolates (105 to 107 cells) as shown by the intensity of the brown pigment. Download Figure S3, PDF file, 0.866 MB.

Phagocytosis assay. Contrasted phagocytic indexes for two ClinCn isolates compared to H99 assessed by FACS-YMI (left panel) and fluorescence microscopy (right panel). The number of Calcohigh FITCneg events (intracellular yeasts) is reported above the gates. Blue-fluorescent C. neoformans cells are intracellular, whereas blue and green fluorescent C. neoformans cells are extracellular (right panel). Download Figure S4, PDF file, 0.844 MB.

Proliferation assay. Contrasted proliferation indexes (IPH2 and IPH48) for two ClinCn isolates compared to H99 assessed using FACS-YMI at 2 h (H2), 24 h (H24), and 48 h (H48) of coincubation. The proportion of Calcohigh, Calcomedium, and Calcolow events in the APCpos and FITCneg gates is reported above each gate. Download Figure S5, PDF file, 0.903 MB.

The E1 MAb binding level is inversely correlated with PI. Shown is a scatter plot of PI versus the E1 MAb binding level for the 54 ClinCn isolates compared to H99 according to colony morphology recorded as mucous (open circle) or smooth (black circle). The solid line represents the regression line (P = 0.006). Dotted lines show the cutoff values for PI and E1 MAb binding, delineating a significant association with colony morphology (P < 0.0001). Download Figure S6, PDF file, 0.792 MB.

The phenotype of the 54 ClinCn isolates is unrelated to their MLST genotype. Principal component analysis (PCA) analysis was performed based on three interaction parameters (PI, IPH2, and IPH48) and eight mycological parameters (cell and capsule sizes, E1 MAb binding, growth, and chitin content) using MeV software v4.6.1 (Manhattan distance, mean centering mode, and 10 neighbors for KNN imputation). The repartition of each plot upon each axis is reported in the right panel. Each color represents one genotype (n = 11). Download Figure S7, PDF file, 0.807 MB.

Hierarchical clustering analysis of expression of six virulence genes under basal (BsH2) and 2-h intracellular (iH2) conditions in addition to the ClinCn/H99 ratio for PI, IPH2, and IPH48. Pearson correlation and complete linkage analysis generated four clusters together with macrophage interaction parameters. The iH2 expression of IPC1, VAD1, APP1, PLB1, and COX1 clustered with IPH48 (cluster 4), while LAC1 iH2 expression clustered with IPH2 (cluster 2), and all BsH2 gene expression levels clustered together (cluster 3), except LAC1 BsH2 expression, which clustered with PI (cluster 1). Download Figure S8, PDF file, 0.830 MB.

Primers and PCR conditions used to assess relative quantification of known virulence genes in this study

Dynamic imaging of calcofluor-labeled H99 C. neoformans cell-macrophage interactions using the Nikon Biostation IM. The movie began 1 h after coincubation between opsonized C. neoformans cells and J774 macrophages. An image was taken every 5 min for 24 h at ×40 magnification using transmitted light and fluorescence microscopy (DAPI filter). Dark blue arrows, mother C. neoformans cells; light blue arrows, daughter C. neoformans cells; white arrows, mitosis of C. neoformans-containing macrophages; red arrows, repartition of C. neoformans cells in the two separated macrophage cells after mitosis; yellow arrows, fusion of the previously separated macrophage cells. Download Movie S1, MOV file, 6.458 MB.