Abstract

Objective

Common diseases often have an inflammatory component reflected by associated markers such as serum CRP levels. Circulating CRP levels have also been associated with adipose tissue as well as with specific CRP genotypes. We examined the interaction between measures of BMI, waist circumference and fat % (total fat measured by bioimpedance) with genotypes of the CRP gene in the determination of CRP levels.

Methods

The first 2296 participants (mean age 76±6 years, 42% men) in the AGES-Reykjavik Study, a multi-disciplinary epidemiological study to determine risk factors in aging, were genotyped for 10 SNPs in the CRP gene. General linear models with age and terms for interaction of CRP genotypes with BMI, waist circumference, and percent fat were used to evaluate the association of genotypes to CRP levels (high sensitivity method, range 0- 10 mg/L) in men and women separately.

Results

We focused on the SNP rs1205 which represents the allele that captures the strongest effects of the gene on CRP levels. Carriers of the rs1205 G allele had significantly higher CRP levels than non-carriers in a dose-dependent manner, The slope of the increase in CRP with increasing BMI (p=0.045) and waist circumference (p=0.014) was lower for AA homozygous men but did not reach statistical significance in women. The rs1205 interactions were not significant for total body fat suggesting an association with fat localization.

Conclusions

The rs1205 SNP in the CRP gene is associated with circulating CRP levels in a manner dependent on BMI and waist circumference in men. This suggests an influence of fat distribution on the production of low grade inflammatory markers.

Keywords: CRP gene, CRP levels, adiposity, gene/environment interaction, AGES-Reykjavik Study

Introduction

CRP has been implicated as a marker of systemic low-grade inflammation. Elevated circulating CRP levels have been found in Alzheimer´s disease 1, 2 as well as in common diseases such as cardiovascular disease 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and type 2 diabetes mellitus T2DM 8, 9, 10 suggesting that these common diseases could have an inflammatory connection.

CRP is primarily produced in the liver and synthesis is regulated by other inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 11, 12, 13 However, in obese individuals an important part of the circulating CRP is produced in adipose tissue 14. Circulating CRP levels have been shown to be associated with adipose tissue, and total body fat has been shown to be a predictor of CRP levels. There is evidence for a different degree of participation of the different adipose tissue compartments 15. Visceral adipose tissue has been shown to be a promoter of low grade CRP-inflammation 16,17 and can produce higher levels of Il-6 than subcutaneous fat 18

Circulating CRP levels have been associated to some extent with common variation in several genes 19 but primarily CRP gene variation 19,20,21. This is reviewed in detail in an article by Fadi G. Hage, Alexander J. Szalai 6. Katherisan et al 22 constructed a linkage disequilibrium map and found associations between individual SNPs and CRP levels, and one common triallelic CRP SNP that is modestly associated with serum CRP levels. Additionally, genetic variation asociated with CRP levels has been associated with coronary heart disease 21 or acute myocardial infarction 23. Lange et al 4 found genetic association with CRP levels as well as CVD risk in the elderly. However, there are a number of other studies that have not been able to identify an association between CRP genotype and the risk of CVD 24,25,26.

The two major factors consistently influencing circulating CRP levels are adipose tissue 14–17 and the CRP gene itself 4, 20–22. The aim of this study was to analyse the effects of CRP gene polymorphisms on CRP levels in a cohort of older Icelanders and determine if there is interaction between various measures of adiposity, and genotypes of the CRP gene in the determination of CRP levels.

Methods and Materials

Study Population

This sample is drawn from the first 2,296 participants who were enrolled in the Age Gene/Environment Susceptibility (AGES)-Reykjavik Study (mean age 76±6 years, 42% men). The AGES-Reykjavik Study is a follow up of the original Reykjavik Study 27, started in 1967 by the Icelandic Heart Association (IHA) where all inhabitants in the Reykjavik area, born 1907–1935, were invited to participate, comprising approximately 30.000 individuals. AGES-Reykjavik is an epidemiologic study that focuses on four biologic systems: vascular, neurocognitive, musculoskeletal and body composition and was initiated in 2002 to investigate the contribution of genetic and environmental risk factors and their interactions to disorders of importance in old age. All participants signed an informed consent form and the AGES-Reykjavik Study is approved by the Icelandic National Bioethics Committee (VSN: 00-063), the Data Protection Authority and the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute on Aging. A more detailed description of the AGES-Reykjavik study and collection of data can be found elsewhere28.

Measurements

Blood pressure and anthropometric data including BMI and waist circumference were collected using standardized protocols 28. Individuals missing either BMI or waist circumference measurements were excluded. A Xitron HYDRA ECF/ICF, Model 4200, was used to measure body composition with the bio-electrical impedance method (BIA) to assess the composition of the total body. From these BIA data, and additional variables such as age, gender and body weight, the fat-free mass (FFM, in kg) of the body can be estimated using prediction equations. Fat mass (FM, in kg) can subsequently be calculated as body weight minus FFM.

High sensitivity CRP was measured on an Hitachi 912, using reagents from Roche Diagnostics and following the manufacturer’s instructions. Both within- and between-assay quality control procedures were used and the coefficient of variation of the method was 1.3% to 3.4%, respectively, through the period of data collection. The assay could detect a minimal CRP concentraton of 0.1 mg/L and values below this level were classified as undetectable. All participants in this study had detectable CRP levels. Persons (145) with CRP levels greater than 10 mg/L were excluded, as this high level of CRP was considered to be due to the acute-phase response.

Fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and triglycerides were also measured on a Hitachi 912, using reagents from Roche Diagnostics and following the manufacturer’s instructions. Trained interviewers administered a health history questionnaire to obtain smoking history information (ever smokers).

The ten SNPs in the CRP gene: rs2808630, rs2808631, rs1205, rs1130864, rs1800947, rs1417938, rs3093062, rs2027471, rs1341665 and rs2808634, were analysed using an Illumina Golden gate assay performed by Illumina in San Diego. These SNPs were chosen as candidate SNPs to cover the CRP gene in a larger group of candidate genes as part of a cardiovascular panel. The SNPs are overlapping with SNPs as used in other studies 21,22. Two SNPs (rs2808631 and rs3093062) were non-polymorphic in the samples examined and DNA samples from seven individuals failed to be genotyped.

Statistical analyses

CRP was log-transformed and analysed with general linear regression models by sex and adjusted for age. rs1205 was entered as a categorical variable with genotype AA as the reference. Association with body fat measurements was estimated by genotype-specific slopes by introducing interaction terms. The significance of the interaction was found by testing the hypothesis of equal slopes between genotypes based on an F-test from the general linear model. The level of significance was set at 0.05. We analyzed the data using SAS/STAT® software, version 9.1.

Results

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the study cohort. Women have higher CRP levels than men as expected, and higher fat mass %. There is a significant increase in serum CRP levels with increasing BMI (r = 0.26, r2 =0.07, p <0.0001), waist circumference (r = 0.21, r2=0.05, p <0.0001) and fat mass % (r= 0.21, r2= 0.05, p <0.0001) in both sexes. These factors account for 5–7% of the variance of CRP levels, shown by r2.

Table 1.

General characteristics

| Characteristics | MEN | WOMEN | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD / 95%CI) | n | Mean (SD / 95%CI) | |

| Age (years) | 904 | 76.3 (5.6) | 1226 | 76.2 (5.8) |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 904 | 142.4 (20.4) | 1226 | 141.6 (21.2) |

| Anthrompometric measures | ||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 904 | 26.6 (3.6) | 1226 | 26.9 (4.8) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 904 | 101.8 (10.3) | 1226 | 99.7 (12.9) |

| Fat percent, % | 757 | 32.8 (6.5) | 923 | 42.4 (5.6) |

| Blood measurements | ||||

| CRP, mg/L* | 904 | 1.73 (0.75;3.98) | 1226 | 1.86 (0.80;4.29) |

| Glucose, mM | 904 | 6.0 (1.2) | 1226 | 5.7 (1.0) |

| Cholesterol, mM | 904 | 5.3 (1.0) | 1226 | 6.1 (1.1) |

| HDL, mM | 904 | 1.4 (0.4) | 1226 | 1.7 (0.4) |

| Triglycerides, mM* | 904 | 1.07 (0.68;1.69) | 1226 | 1.14 (0.73;1.78) |

geometric means

The observed allele frequencies for all SNPs were consistent with expectation under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p<0.01). Linkage disequilibrium (LD) values (r2) are shown in Table 2a. The following individual SNPs, rs1205, rs1130864, rs1800947, rs1417938, rs2027471, and rs1341665, were significantly associated with CRP levels, when tested individually after adjusting for age and sex, (Table 2b). There was a dose dependent decrease in CRP levels with the minor allele of rs1205 in men (Table 3). Looking at the LD values in Table 2a, there are three distinct groups of tagging SNPs that can be observed: 1. rs1800947 does not capture the effect of other SNPs 2. rs1205 captures the effects of rs2027471 and rs1341665, 3. rs1130864 captures the effect of rs1417938 on CRP levels. Haplotypes derived from these SNPs were tested and no clear evidence for stronger association to CRP levels with any one haplotype as compared to individual SNPs was observed.

Table 2.

| a. Linkage disequilibrium of SNPs (3’-5’ order) tested in the CRP gene. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD(r2) | rs2808630 | rs1205 | rs1130864 | rs1800947 | rs1417938 | rs2027471 | rs1341665 | rs2808634 |

| rs2808630 | 1 | 0,197995 | 0,187928 | 0,0281943 | 0,191442 | 0,205566 | 0,205915 | 0,975775 |

| rs1205 | 1 | 0,222652 | 0,143046 | 0,2231 | 0,967392 | 0,965347 | 0,191156 | |

| rs1130864 | 1 | 0,0318752 | 0,994888 | 0,22812 | 0,226536 | 0,202133 | ||

| rs1800947 | 1 | 0,0324988 | 0,141475 | 0,141725 | 0,0277186 | |||

| rs1417938 | 1 | 0,228684 | 0,227288 | 0,204529 | ||||

| rs2027471 | 1 | 0,998964 | 0,198381 | |||||

| rs1341665 | 1 | 0,198719 | ||||||

| rs2808634 | 1 | |||||||

| b. Correlation of genotypes of individual SNPs in the CRP gene with CRP levels. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | MAF | Beta† | p-value |

| rs2808630 | 0.31 | −0.037 | 0.19 |

| rs1205 | 0.31 | −0.116 | 3.1*10−5 |

| rs1130864 | 0.32 | 0.110 | 7.7*10−5 |

| rs1800947 | 0.06 | −0.235 | 5.2*10−6 |

| rs1417938 | 0.32 | 0.115 | 3.7*10−5 |

| rs2027471 | 0.32 | −0.103 | 1.9*10−4 |

| rs1341665 | 0.32 | −0.101 | 2.8*10−4 |

| rs2808634 | 0.30 | −0.044 | 0.12 |

Beta values are relative to the major allele.

Table 3.

CRP levels according to rs1205 genotypes, adjusted for age and excluding CRP >10mg/L

| MEN rs1205 | CRP mg/L (95%CI)† | p |

| AA n=77 | 1.33 (1.11 ; 1.60) | |

| AG n=411 | 1.69 (1.54 ; 1.80) | 0.0313‡ |

| GG n=421 | 1.89 (1.75 ; 2.04) | 0.0007 |

| WOMEN rs1205 | CRP mg/L (95%CI) † | p |

| AA n=119 | 1.54 (1.33 ; 1.80) | |

| AG n=562 | 1.86 (1.74 ; 2.00) | 0.0261 |

| GG n=554 | 1.94 (1.80 ; 2.08) | 0.0077 |

geometric means

Between AG and GG p=0.0256

All SNPs were tested to see if the effects of anthropometric factors on CRP levels vary across genotypes. A significant effect was found with SNPs rs1205, rs2027471 and rs1341665. As discussed above the two latter SNPs rs2027471 and rs1341665 are in complete linkage disequilibrium with rs1205 and do not capture any signal independent of and beyond that observed between rs1205 and CRP levels, adjusted for sex and age as expected from the LD. Therefore, we focused on the SNP rs1205 which represents the allele that captures the strongest effects of the gene on CRP levels. Another SNP rs1800947 is also strongly associated with CRP levels, but the MAF of rs1800947 is so low it is difficult to fully analyse this SNP in the context of interaction with BMI.

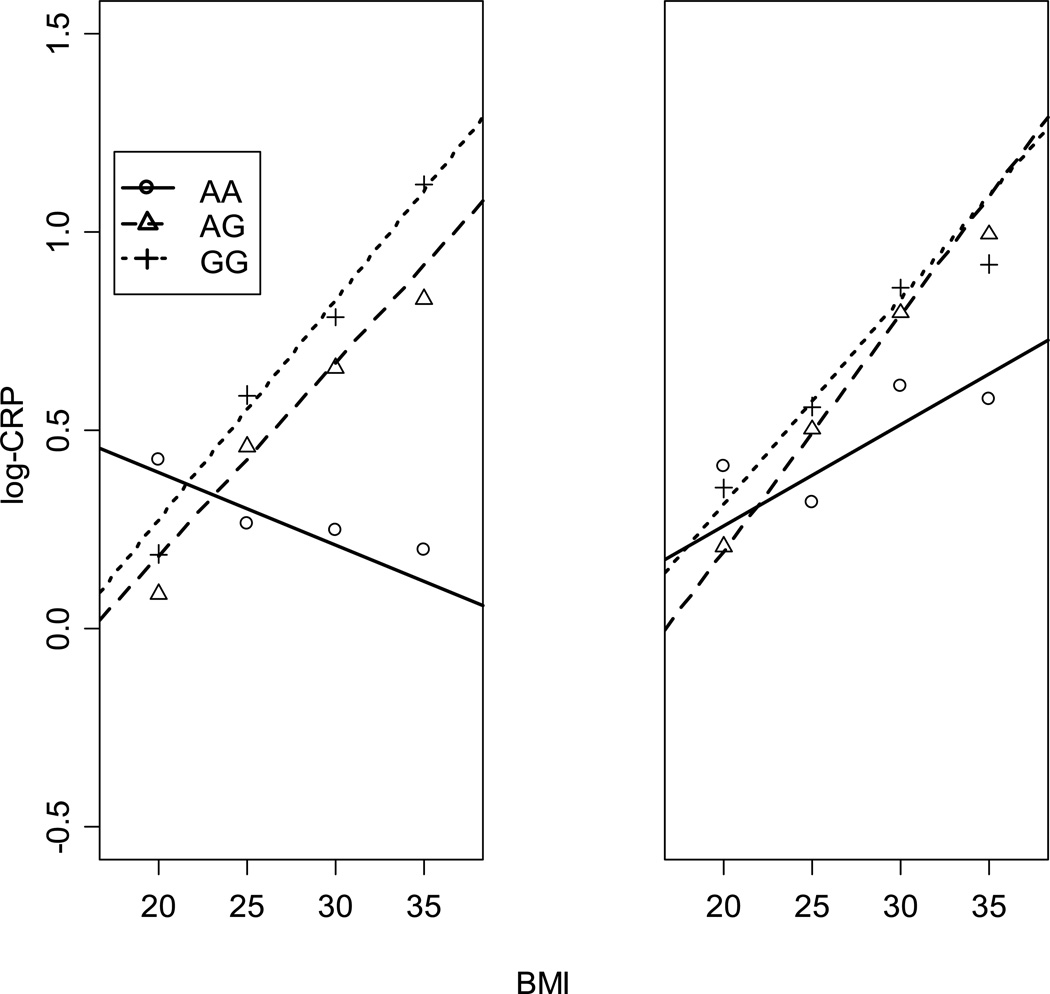

The interaction of BMI, waist circumference and fat mass % with genotypes of rs1205 on CRP levels for both men and women is shown in Table 4. There is interaction between BMI (p=0.045 ) and rs1205 and also between waist circumference and rs1205 (p=0.014) in men only as shown by the beta coefficients of the association. The increase in CRP levels with BMI and waist circumference is significantly different for the AA genotype than for the GA and GG genotypes in men. This association for BMI and CRP levels is shown in Figure 1. However, this is not the case for fat mass %. BMI and waist circumference are highly correlated factors, though BMI and fat mass % are only moderately correlated. No significant interaction was found between anthropometric factors and genotype in women although the slope for the increase in CRP levels with BMI in AA homozygotes is not as steep as for the G allele carriers.

Table 4.

Interaction between the rs1205 genotype and anthropometric measurements on circulating CRP levels.

| rs1205 genotype | BMI | N=904 | WC | N=904 | F% | N=754 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEN | β-coefficient | SE | β- coefficient | SE | β-coefficient | SE |

| AA | −0.003 | 0.022 | −0.006 | 0.008 | 0.030 | 0.018 |

| AG | 0.049 | 0.011 | 0.015 | 0.004 | 0.021 | 0.007 |

| GG | 0.060 | 0.011 | 0.020 | 0.004 | 0.032 | 0.007 |

| p for interaction | 0.045 | 0.014 | 0.563 | |||

| WOMEN | BMI | N=1226 | WC | N=1226 | F% | N=923 |

| AA | 0.031 | 0.017 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.025 | 0.017 |

| AG | 0.065 | 0.007 | 0.017 | 0.003 | 0.028 | 0.007 |

| GG p for interaction |

0.048 0.088 |

0.007 | 0.015 0.780 |

0.003 | 0.050 0.054 |

0.007 |

BMI = body mass index

WC = waist circumference

F% = fat mass %

Figure 1.

The association of BMI with logCRP in rs1205 genotypes. The increase in CRP levels with BMI is significantly different (p<0.05) for the AA genotype than for the GA and GG genotypes in men (left view) but not in women (right view). The marks (dot, triangle, and cross) represent mean log-CRP values by genotypes around bmi values of 20, 25, 30, and 35 using bins of width 5.

Discussion

Measuring of inflammatory markers has been used to try to improve the prediction of common diseases. CRP is one such inflammatory marker that has been associated with common disease including coronary heart disease and diabetes and therefore it is important to know what factors can influence CRP levels. The results reported here are consistent with many studies where polymorphisms in the CRP gene are associated with CRP levels. In addition the results presented here confirm the effect of adipose tissue on circulating CRP levels found in other studies. The novel finding in this study is the interaction of adiposity with CRP genotypes to influence CRP levels with the relationship stronger in men than in women. This interaction is seen between BMI and CRP genotype and also between waist circumference and CRP genotype, but is statistically significant in men only.

Total body fat has been shown to be a good predictor of circulating CRP levels but it is also important to understand the relevance of fat distribution in the production of low grade inflammatory markers. BMI, total body fat, and waist circumference, thought to be a surrogate for visceral fat, are shown here to be positively associated with CRP levels, in both men and women. The AA genotype of the rs1205 SNP is associated with low CRP levels. In men, BMI and waist circumference have a different effect on CRP levels in individuals with the AA genotype of the rs1205 SNP than carriers of the G allele. The association of the adiposity measurements with CRP levels is carried by the AG and GG genotypes. On the other hand the rs1205 interactions were not significant for total body fat. These results support other studies where visceral fat has been shown to be important as a promotor of moderately increased CRP levels 16 and in addition suggest gene/environment interaction where the fat tissue type and localization modifies the expression of the CRP gene. In women, the effect is in the same direction but not statistically significant. The difference between the sexes can in part be explained by the fact that men, of the same age and BMI, have a different fat distribution 17 than women, with less subcutaneous fat and proportionally more visceral fat. This in turn further supports the possibility that it is the visceral fat that produces a factor that interacts with the CRP gene and calls out for using more detailed fat measures.

The AA genotype of the rs1205 SNP involved in the interaction effects with adiposity measures shown in this study has also been found to be associated with lower cardiovascular mortality 4. The effect of this genotype on CRP levels could partly explain the relationships between central body fat depots and cardiovascular risk complications. Genetic effects in common diseases are generally small 26, 29 but gene environment interaction such as reported here could be important in modulating risk for common diseases.

Many studies have put emphasis on determining haplotype effect on disease. Risk haplotypes in the CRP gene have been reported for cardiovascular disease 22 and diabetes 30,31 and CRP level has been shown to be an independent risk factor for both these common diseases although not over and above other known risk factors 3. In our data these haplotypes did not add to the effect on CRP levels beyond the effect of the single SNP, rs1205. This is most likely reflected in the fact that there is extremely strong LD over the CRP gene as identified with our panel of SNPs and has been discussed in a recent review paper 6.

In summary, in men the effect of BMI and waist circumference on the levels of circulating CRP may be mediated through the CRP gene with the possibility that there may be an adipose tissue produced factor that affects the CRP gene expression.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health contract N01-AG-12100, the National Institute on Aging Intramural Research Program, Hjartavernd (the Icelandic Heart Association), and the Althingi (the Icelandic Parliament).

REFERENCES

- 1.Finch CE, Morgan T. Systemic inflammation, infection, ApoE alleles, and Alzheimer disease: a position paper. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4(2):185–189. doi: 10.2174/156720507780362254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaciragic ALO, Valjevac A, Arslanagic S, Fajkic A, Hadzovic-Dzuvo A, Avdagic N, Alajbegovic A, Mehmedika-Suljic E, Coric G. Elevated serum C-reactive protein concentration in Bosnian patients with probable Alzheimer's disease. Elevated serum C-reactive protein concentration in Bosnian patients with probable. J Alzheimer's disease. 2007;12(2):151–156. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-12204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danesh JWJ, Hirschfield GM, Eda S, Eiriksdottir G, Rumley A, Lowe GD, Pepys MB, Gudnason V. C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2004 Apr 1;350(14):1387–1397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032804. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lange LACC, Hindorff LA, Lange EM, Walston J, Durda JP, Cushman M, Bis JC, Zeng D, Lin D, Kuller LH, Nickerson DA, Psaty BM, Tracy RP, Reiner AP. Association of polymorphisms in the CRP gene with circulating C-reactive protein levels and cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2006;296(22):2703–2711. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.22.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melanie Kolz WK, Müller Martina, Andreani Mariarita, Greven Sonja, Thomas Illig NK, Panagiotakos Demosthenes, Pershagen Göran, Veikko Salomaa JS Annette Peters for the AIRGENE Study Group. DNA variants, plasma levels and variability of C-reactive protein in myocardial infarction survivors: results from the AIRGENE study. Eur Heart J. 2007 oct. 22 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm442. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fadi G, Hage MaAJS. C-Reactive Protein Gene Polymorphisms, C-Reactive Protein Blood Levels, and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1115–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sattar Naveed, MHMM, MSc, McConnachie Alex, PhD, Blauw Gerard J, MD, Bollen Edward LEM, MBMB, FRCPI, Cobbe Stuart M, MD, Ford Ian, PhD, Gaw Allan, MMH, FRCPI, Jukema J Wouter, MD, Kamper Adriaan M, MD, Macfarlane Peter W, DMBM, MD, Packard Chris J, DSc, Perry Ivan J, MD, Stott David J, MBJS, FRCPI, Twomey Cillian, FRCPI, Westendorp Rudi GJ, MD, Shepherd James., PftPSG C-Reactive Protein and Prediction of Coronary Heart Disease and Global Vascular Events in the Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER) Circulation. 2007 Feb 5;:115. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.643114. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbas Dehghan IK, de Maat Moniek PM, Uitterlinden Andre G, Sijbrands Eric JG, Bootsma Aart H, Stijnen Theo, Hofman Albert, Schram Miranda T, Witteman Jacqueline CM. Genetic Variation, C-Reactive Protein Levels, and Incidence of Diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:872–878. doi: 10.2337/db06-0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman DJNJ, Caslake MJ, Gaw A, Ford I, Lowe GD, O'Reilly DS, Packard CJ, Sattar N. C-reactive protein is an independent predictor of risk for the development of diabetes in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Diabetes. 2002 May;51(5):1596–1600. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1596. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pradhan ADMJ, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001 Jul 18;286(3):327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kushner IS-LJ, Dongxiao Zhang, Gerard Lozanski, David Samols. Do post-transcriptional mechanisms participate in induction of C-reative protein and serum amyloid A by IL-6 and IL-1? Ann NY Acad Sci. 1995;762:102–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb32318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yudkin JSa, Stehouwer CDAb, Emeis JJc, Coppack SWa. C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: Associations with obesity, insulin resistance, and endothelial dysfunction: A potential role for cytokines originating from adipose tissue? Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 1999;19(4):972–978. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.4.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bastard JP, Maachi M, Lagathu C, Kim MJ, Caron M, Vidal H, Capeau J, Feve B. Recent advances in the relationship between obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance. European cytokine network. 2006;17(1):4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anty RBS, Luciani N, Saint-Paul MC, Dahman M, Iannelli A, Amor IB, Staccini-Myx A, Huet PM, Gugenheim J, Sadoul JL, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Tran A, Gual P. The inflammatory C-reactive protein is increased in both liver and adipose tissue in severely obese patients independently from metabolic syndrome, Type 2 diabetes, and NASH. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006 Aug;101(8):1824–1833. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00724.x. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Memoli BPA, Calabrò P, Esposito P, Grandaliano G, Pertosa G, Prete MD, Andreucci M, Lillo SD, Ferulano G, Cillo C, Savastano S, Colao A, Guida B. Inflammation may modulate IL-6 and C-reactive protein gene expression in the adipose tissue: the role of IL-6 cell membrane receptor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Oct 29;293(4):E1030–E1035. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00697.2006. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forouhi NGSN, McKeigue PM. Relation of C-reactive protein to body fat distribution and features of the metabolic syndrome in Europeans and South Asians. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001 Sep;25(9):1327–1331. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801723. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visser MBL, McQuillan GM, Wener MH, Harris TB. Elevated C-reactive protein levels in overweight and obese adults. JAMA. 1999 Dec 8;282(22):2131–2135. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.22.2131. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fried SK, Bunkin DA, Greenberg AS. Omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues of obese subjects release interleukin-6: depot difference and regulation by glucocorticoid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998 Mar;83(3):847–850. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ridker PM, Pare G, Parker A, Zee RY, Danik JS, Buring JE, Kwiatkowski D, Cook NR, Miletich JP, Chasman DI. Loci related to metabolic-syndrome pathways including LEPR,HNF1A, IL6R, and GCKR associate with plasma C-reactive protein: the Women's Genome Health Study. Am J Hum Genet. 2008 May;82(5):1185–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carlson Christopher S, SFA, Lee Philip K, Tracy Russell P, Schwartz Stephen M, MR, Liu Kiang, Williams O Dale, Iribarren Carlos, Lewis E Cora, MF, Boerwinkle Eric, Gross Myron, Jaquish Cashell, Nickerson Deborah A, RMM, Siscovick David S, Reiner Alexander P. Polymorphisms within the C-Reactive Protein (CRP) Promoter Region Are Associated with Plasma CRP Levels. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:64–77. doi: 10.1086/431366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crawford Dana C, PCLS, MS, Qin Xiaoting, PhD, Smith Joshua D, BS, Shephard Cynthia, BS, Wong Michelle, BS, Witrak Laura, BA, Rieder Mark J, PhD, Nickerson Deborah A., PhD Genetic Variation Is Associated With C-Reactive Protein Levels in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Circulation. 2006;114:2458–2465. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.615740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kathiresan SLM, Vasan RS, Guo CY, Gona P, Keaney JF, Jr, Wilson PW, Newton-Cheh C, Musone SL, Camargo AL, Drake JA, Levy D, O'Donnell CJ, Hirschhorn JN, Benjamin EJ. Contribution of clinical correlates and 13 C-reactive protein gene polymorphisms to interindividual variability in serum C-reactive protein level. Circulation. 2006 Mar 21;113(11):1415–1423. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591271. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balistreri CR, Vasto S, Listì F, Grimaldi MP, Lio D, Colonna-Romano G, Caruso M, Caimi G, Hoffmann E, Caruso C, Candore G. Association between + 1059G/C CRP polymorphism and acute myocardial infarction in a cohort of patients from Sicily: a pilot study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006 May;1067:276–281. doi: 10.1196/annals.1354.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pai JKMK, Rexrode KM, Rimm EB. C-Reactive Protein (CRP) Gene Polymorphisms, CRP Levels, and Risk of Incident Coronary Heart Disease in Two Nested Case-Control Studies. PLoS ONE. 2008 Jan 2;3(1):e1395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang QHS, Xu Q, Chen YE, Province MA, Eckfeldt JH, Pankow JS, Song Q. Association study of CRP gene polymorphisms with serum CRP level and cardiovascular risk in the NHLBI Family Heart Study. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006 May 26;291(6):H2752–H2757. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01164.2005. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kardys I, Knetsch AM, Bleumink GS, Deckers JW, Hofman A, Stricker BH, Witteman JC. C-reactive protein and risk of heart failure. The Rotterdam Study. Am Heart J. 2006 Sep;152(3):514–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jónsdóttir LSSN, Sigvaldason H, Thorgeirsson G. Incidence and prevalence of recognised and unrecognised myocardial infarction in women. The Reykjavik Study. Eur Heart J. 1998;19(7):1011–1018. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.0980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris TBLL, Eiriksdottir G, Kjartansson O, Jonsson PV, Sigurdsson G, Thorgeirsson G, Aspelund T, Garcia ME, Cotch MF, Hoffman HJ, Gudnason V. Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study: multidisciplinary applied phenomics. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(9):1076–1087. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danik JS, Ridker PM. Genetic determinants of C-reactive protein. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2007;9(3):195–203. doi: 10.1007/s11883-007-0019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dehghan AKI, de Maat MP, Uitterlinden AG, Sijbrands EJ, Bootsma AH, Stijnen T, Hofman A, Schram MT, Witteman JC. Genetic variation, C-reactive protein levels, and incidence of diabetes. Diabetes. 2007 Mar;56(3):872–878. doi: 10.2337/db06-0922. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zee RYGS, Thomas A, Raji A, Rhees B, Ridker PM, Lindpaintner K, Williams GH, Nathan DM, Martin M. C-reactive protein gene variation and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A case-control study. Atherosclerosis. 2007 Sep 25;:2007. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]