Abstract

Motivation: Mathematical models of complex biological systems usually consist of sets of differential equations which depend on several parameters which are not accessible to experimentation. These parameters must be estimated by fitting the model to experimental data. This estimation problem is very challenging due to the non-linear character of the dynamics, the large number of parameters and the frequently poor information content of the experimental data (poor practical identifiability). The design of optimal (more informative) experiments is an associated problem of the highest interest.

Results: This work presents AMIGO, a toolbox which facilitates parametric identification by means of advanced numerical techniques which cover the full iterative identification procedure putting especial emphasis on robust methods for parameter estimation and practical identifiability analyses, plus flexible capabilities for optimal experimental design.

Availability: The toolbox and the corresponding documentation may be downloaded from: http://www.iim.csic.es/~amigo

Contact: ebalsa@iim.csic.es

1 INTRODUCTION

Dynamic modeling and simulation are becoming standard approaches to understand complex biological systems. Model identification is at the core of model building, and involves the computation of unknown non-measurable parameters by means of experimental data fitting (Jaqaman and Danuser, 2006). However, parametric identification is a bottleneck in the modeling process due to, mainly, the frequently ill-possed and multimodal nature of the associated optimization problems, and the poor practical identifiability due to lack of information in the available experimental data.

The use of suitable optimization methods to avoid local solutions has been illustrated during the last decade by many authors, and some of these methods have been incorporated in software tools such as: COPASI (Hoops et al., 2006), SBToolbox2 (Schmidt and Jirstrand, 2006), PottersWheel (Maiwald and Timmer, 2008) or SensSB (Rodriguez-Fernandez and Banga, 2010). These software packages allow the dynamic simulation and analysis of systems biology models, including methods for sensitivity analysis and parameter estimation and, in some cases, some basic facilities for experimental planning.

Here, we present the result of our research efforts in the development of procedures to improve practical identifiability and to help in the design of informative experiments. The underlying idea is to help the system biologist on how to stimulate and observe the system for the purpose of model identification.

2 SUMMARY OF FEATURES

AMIGO is the first multiplatform (Windows and Linux) environment which covers all the steps of the iterative identification procedure (Balsa-Canto et al., 2010). Its ultimate goal is to enable the computation of model unknowns with the maximum accuracy and at a minimum experimental cost, offering:

maximum flexibility for the definition of models and observation functions;

multiexperiment tasks with local (experiment dependent) and global information;

multiple types of experimental noise conditions and, accordingly, different types of cost functions for parameter estimation and experimental design;

maximum flexibility for the definition of unknowns: parameters and initial conditions that may be local (experiment dependent) or global for all tasks;

several approaches to perform identifiability analyses;

sequential-parallel optimal experimental designs formulated as general optimal control problems; and

a suite of state of the art numerical methods for both simulation and optimization to cover a broad range of problems: integration of stiff, non-stiff and/or sparse dynamic systems, plus solvers for convex and multimodal non-linear optimization problems.

2.1 Problem definition

Types of models: AMIGO supports general non-linear dynamic models using a simple syntax. Users can also import SBML models, or work with arbitrary black-box user-defined models, allowing the handling of partial differential, general differential and algebraic or delay differential equations.

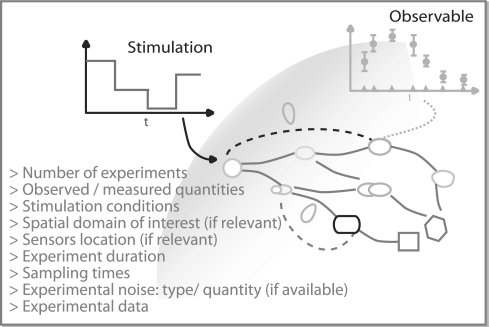

Definition of the experimental scheme: the experimental scheme describes the conditions under which the experiments were (or are to be) performed at the wet lab (Fig. 1). Users can define multiexperimental schemes with maximum flexibility over experiments—observables, stimulation profiles, initial conditions, experiment durations and sampling times—that are to be performed in silico or to be optimally designed. Any linear or non-linear observation functions are accepted and several typical stimulation conditions (sustained, pulse-wise, step-wise or measured) are already predefined to ease their implementation.

Fig. 1.

Illustrative example of the experimental scheme and data.

Definition of the experimental data: it allows the loading of real experimental data with different types of Gaussian experimental noise, homoscedastic with known constant variance, homoscedastic with known varying variance, i.e. with error bars determined by experiments replicates or heteroscedastic with power on the mean variance.

Definition of model unknowns: it offers the possibility of defining local (experiment dependent) or global (experiment independent) model unknowns (parameters and initial conditions).

2.2 Available tasks

Simulation: the toolbox offers several dynamic simulation tasks (AMIGO_SModel, AMIGO_SObs and AMIGO_SData) to solve system dynamics under given values of model unknowns and given experimental schemes. AMIGO_SModel and AMIGO_SObs solve the system dynamics and depict states and observables plots, respectively. AMIGO_SData solves the system dynamics and plots observables together with experimental data, if available, or generates pseudoexperimental data to perform numerical tests.

Sensitivity analysis and rank of parameters: AMIGO_LRank and AMIGO_GRank allow multiexperiment local and global sensitivity analysis, respectively, for local and global model unknowns. The overall results are collected into a rank of the unknowns to asses their relative influence in the observables. The sensitivities of the different observables with respect to selected unknowns for the given experiments are also provided so as to obtain information about possible identifiability problems and clues for the purpose of experimental design.

Parameter estimation: AMIGO_PE allows for multiexperiment fitting of local and global unknowns. Several types of weighted least squares and log-likelihood functions may be used depending on the available information about the experimental noise. The optimal solution will be accompanied by the confidence intervals as computed by means of the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM).

Practical identifiability analysis: as well as the use of sensitivity analysis and the computation of FIM-based confidence intervals, the tool offers two additional tasks to complete the identifiability analysis. AMIGO_Contourp plots 2D projections of the parameter estimation cost function so as to assess multimodality and poor or lack of identifiability by pairs of parameters. AMIGO_RIdent performs a robust analysis using a Monte Carlo-based approach to generate the robust confidence hyperellipsoid and to provide relevant information regarding correlation of the parameters and robust confidence intervals.

Optimal experimental design: the toolbox can solve the optimal sequential-parallel experimental design problem as a truly general optimal control problem (Balsa-Canto et al., 2008a). It allows the optimization of the number and location of sampling times, stimulation profiles, initial conditions and experiment durations for one or more simultaneous experiments. Sequential-parallel designs are possible so as to allow for the new optimally designed experiments to be complementary to existing experiments. Several FIM-based formulations have been incorporated so as to handle the different types of experimental noise.

2.3 Numerical methods

AMIGO incorporates a suite of state of the art initial value problem (IVP) and non-linear optimization (NLP) methods in order to handle different types of problems.

Regarding IVP solvers, explicit and implicit Runge-Kutta of several orders and Adams methods have been incorporated to deal with non-stiff or mildly-stiff dynamic systems; methods based on the backward differentiation formulae (BDF) are available to solve stiff models and methods using sparse algebra may be used for large-scale models. Implementations of the methods are available both for MATLAB and FORTRAN (the latter allows a significant reduction of computation times).

Several options are also offered to compute parametric sensitivities, either using the direct approach based on BDF methods or by means of finite differences schemes.

Regarding NLP solvers, several direct and indirect local methods are available to handle convex problems. However, finding the global optimum for multimodal problems, i.e. those presenting multiple local optima, requires robust and efficient global optimization methods. In this regard, the toolbox offers the multistart of local methods to detect multimodality or poor identifiability and several global stochastic methods.

Despite the fact that many stochastic methods can locate the vicinity of global solutions very rapidly, the computational cost associated to the refinement of the solution is usually large. In order to surmount this difficulty, the toolbox integrates several metaheuristics (Egea et al., 2007), clustering methods (Csendes et al., 2008) and sequential hybrids (Balsa-Canto et al., 2005, 2008b), which combine different mechanisms of global exploration of the search space with the use of local methods to enhance computational efficiency.

See the toolbox documentation for exhaustive lists and references to the available numerical methods.

2.4 Illustrative examples

For illustrative purposes, a number of examples are included with the tool (see folder Examples) covering different types of biochemical networks. The implementation of these examples and the corresponding results are extensively discussed in the AMIGO user guide. In addition, interested readers are referred to the works by Vera et al. (2010) where the tool was used in the modelling of the MEK/ERK/RKIP pathway or Balsa-Canto et al. (2010) where the complete model identification procedure is applied to a NFκB signaling module model.

3 GENERAL STRUCTURE AND IMPLEMENTATION

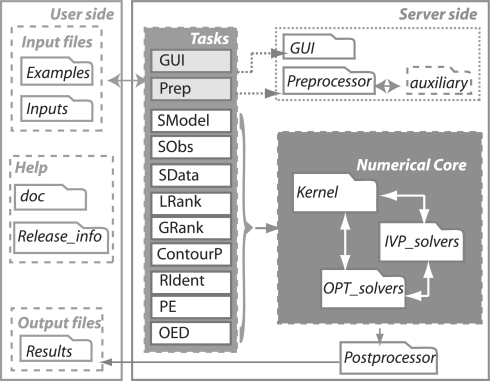

AMIGO has been developed as a modular multiplatform toolbox organized in two major blocks: the user and the server sides (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

AMIGO structure.

The user side consists of the following folders: doc keeps all toolbox-related documentation (user guide, tutorials, etc.); Examples keeps a number of implemented examples that the user may consider as templates to implement new problems; Inputs, originally empty, is devoted to keep new inputs created by users; Results, originally empty, is devoted, by default, to keep all results; Release_info contains the AMIGO_release_info.m file with all details about previous and current releases.

The server side is arranged in four modules: the Preprocessor that generates MATLAB or FORTRAN codes, performs the mex of files when required; the tasks SModel, Sobs, SData, LRank, GRank, PE, ContourP, RIdent and OED that correspond to different steps in the model identification loop; the Kernel that performs the numerical computations and the Postprocessor that post-processes the results to generate output reports, structures and figures.

The toolbox has been implemented in MATLAB, but it also offers the possibility to automatically generate compiled FORTRAN models that AMIGO will link to FORTRAN initial value problem (IVP) solvers, substantially increasing computational efficiency. The user may define and solve different tasks by either using input scripts or by means of a user-friendly graphical interface. The toolbox generates reports, including tables and plots, according to user specifications for the different tasks. Help functions are also present to facilitate the handling of data and results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the different beta-testers, C. Vilas for his contributions regarding multiplatform FORTRAN compilation, J.M. Sánchez-Curto for his contributions to WEB and GUI implementation and M. Pérez-Rodríguez for the AMIGO logo design.

Funding: This work was funded by the EU [CAFE FP7-KBBE-2007-1(212754)]; the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MultiSysBio DPI2008-06880- C03-02, SMART-QC AGL2008-05267-C03-01); the Xunta de Galicia (IDECOP 08DPI007402PR) and the CSIC (PIE 200730I002).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Balsa-Canto E., et al. Dynamic optimization of single-and multi-stage systems using a hybrid stochastic-deterministic method. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2005;44:1514–1523. [Google Scholar]

- Balsa-Canto E., et al. Computational procedures for optimal experimental design in biological systems. IET Syst. Biol. 2008a;2:163–172. doi: 10.1049/iet-syb:20070069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsa-Canto E., et al. Hybrid optimization method with general switching strategy for parameter estimation. BMC Syst. Biol. 2008b;2:26. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-2-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsa-Canto E., et al. An iterative identification procedure for dynamic modeling of biochemical networks. BMC Syst. Biol. 2010;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csendes T., et al. The GLOBAL optimization method revisited. Optim. Lett. 2008;2:445–454. [Google Scholar]

- Egea J.A., et al. Scatter search for chemical and bio-process optimization. J. Global Optim. 2007;37:481–503. [Google Scholar]

- Hoops S., et al. COPASI- A COmplex PAthway SImulator. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:3067–3074. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaqaman K., Danuser G. Linking data to models: data regression. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio. 7:813–819. doi: 10.1038/nrm2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiwald T., Timmer J. Dynamical modeling and multi-experiment fitting with PottersWheel. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2037–2043. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Fernandez M., Banga J.R. SensSB: a software toolbox for the development and sensitivity analysis of systems biology models. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1675–1676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H., Jirstrand M. Systems Biology Toolbox for MATLAB: a computational platform for research in systems biology. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:514–515. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera J., et al. Investigating dynamics of inhibitory and feed back loops in ERK signalling using power-law models. Mol. Biosyst. 2010;6:2174–2191. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00018c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]