Research in social epidemiology over the past three decades has shown convincingly that population health is shaped to a significant degree by fundamental social conditions. The social production of health is sufficiently complex to preclude simple causal attributions, but consistent correlations across populations between health and various measures of social and economic status leave little room for doubt that social arrangements account for an important fraction of population health. Efforts to find the mechanisms of these effects are ongoing, and progress is seen in findings about, for example, the powerful role of stress across the life course.1 Although in the U.S. we tend to hear most about racial/ethnic disparities, these inequities are as much a matter of class as race or ethnicity. Responding to the findings of this social epidemiology is perhaps the true grand challenge of our time in public health. Whether or not it is grand, it is certainly difficult, from both the research and implementation points of view. The efforts of the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention (NCHHSTP), described in a 2010 white paper,2 represent an extremely valuable contribution to meeting the challenge of health inequities. In this commentary, I offer a public health law researcher's thoughts on practical efforts to address the social determinants of health (SDH), and how law and research on law can best support the effort. I distinguish two relationships between law and social determinants and suggest—via a quick tour through the work of Geoffrey Rose3—the importance of integrating law more frequently into behavioral and social health research. Of course, this is epidemiology coming from an attorney, so caveat emptor—let the buyer beware'

“THE LAW IS ALL OVER”

“The law is all over.” I take this phrase from a classic work of socio-legal research,4 which, in turn, is quoting a man's description of navigating the welfare system: wherever he goes, there are rules and officials shaping his entire experience with the system. Law for this man—and for all of us—is not just a distant set of “laws on the books” in Washington, D.C., but the systems, institutions, and practices through which the law is implemented every day “on the streets.” It is not just the formal rules of the welfare system, but how these rules are enacted every day in welfare offices by case workers—and clients—who have their own understanding of what the law is, how it relates to other sets of rules, and how it can advance or hinder their own goals.

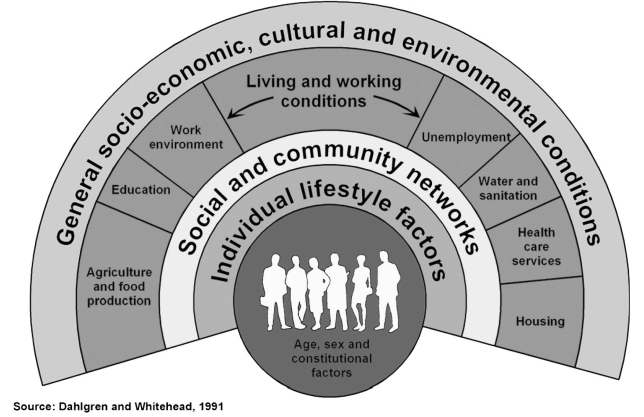

This is important to keep in mind in looking at Dahlgren and Whitehead's well-known depiction of the levels of policy intervention in health (Figure 1).5 It is easy to see how the laws on the books play an important role in setting the structure of the fields in the two outermost bands and, therefore, indirectly influence the inner bands; however, it is just as easy to lose sight of the implementation of law as a direct and daily influence on how people behave, interact, and clump. In other words, we can see two important ways that law interacts with social determinants: (1) law helps structure and perpetuate the social conditions that we describe as “social determinants,” and (2) it acts as a mechanism or mediator through which social structures are transformed into levels and distributions of health.6 This latter role, which tends to play itself out in the law on the streets rather than the law of the books, is too often overlooked in health and health research.

Figure 1.

Dahlgren and Whitehead's Social Model of Health:a a depiction of the levels of policy intervention in health

aDahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Stockholm (Sweden): Institute for Futures Studies; 1991.

Drug policy provides a sad, simple illustration of how law is woven into the structure and events of everyday life. The federal Controlled Substances Act7 and its state equivalents make no distinction of race or ethnicity. Given that black and white people use illegal drugs at just about the same rate, one would expect that they would be incarcerated for drug crimes at about the same rate. Given that black and white people inject heroin at about the same rate, one would expect rates of injection-related human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) to be about the same. We are all aware, however, that rates of both incarceration and injection-related HIV differ dramatically by race. Of course, some of this disparity may have to do with differential rates of offending and even differing community demands for police action, but the broader point is that the way the neutral law is enforced—who is targeted for surveillance and arrest, how people are sorted to jail or treatment, and how all that plays out in communities and social networks—turns out to be a substantial driver of the law's impact. And for HIV, the story goes deeper. There is extensive evidence that drug policing shapes the behavior of drug users and access to and availability of preventive services.8

PUBLIC HEALTH LAW RESEARCH

Public health law research (PHLR), defined as “the scientific study of the relation of law and legal practices,”9 makes its contribution to the effort to address social determinants by empirically studying both of the ways in which law interacts with social conditions. Progress on studying and addressing social determinants has been real, but I suspect we are still somewhere near the end of the beginning. To get this far in our collective thinking has been quite an effort; yet, all sorts of questions—large and small, normative and methodological—remain to be untangled. I will allude to a few of these in these brief remarks, but space limitations impel me to grapple directly with my main questions of (1) how can we collectively make progress, and (2) how can PHLR help?

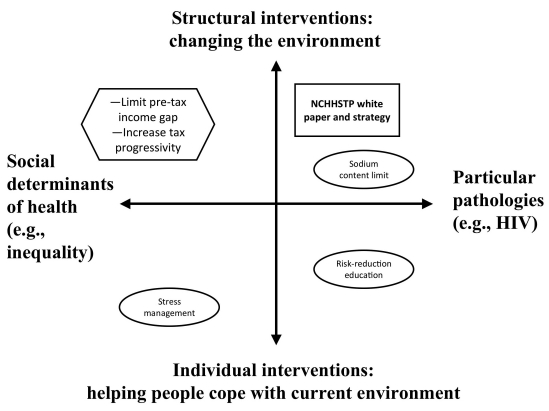

To answer these questions, I have to go back a bit in my career as a public health attorney. My real education in public health began the day I read Rose's landmark article, “Sick Individuals and Sick Populations,”3 a road-to-Damascus epiphany for me. He made a distinction between the causes of cases (i.e., the immediate, personal risk factors that explain why a particular person suffers a particular disease or injury) and the causes of incidence (i.e., why there is a given frequency or proportion of that disease or injury in that population). He illustrated the point with a graph depicting the distribution of systolic blood pressure in two populations: London civil servants and Kenyan nomads. The distribution of individual risk was the same in the two groups, but the bell curve for the London civil servants was shifted several notches in the pathological direction. There were factors in these environments that were helping Kenyans or hurting Londoners. The question this posed to an attorney was whether law might be one of them. The horizontal axis in Figure 2, rephrased in contemporary terms, depicts the spectrum of causation from SDH on the left (causes of incidence) to the causes of particular cases of specific diseases on the right (causes of cases).

Figure 2.

Dimensions of causation from social determinants of health to specific diseases,a and range of interventions from individual to structuralb,c

aThe horizontal axis depicts the spectrum of causation from social determinants of health on the left (causes of incidence) to the causes of particular cases of specific diseases on the right (causes of cases).

bThe vertical axis depicts the range of interventions, from individual (or agentic) interventions, which help people adapt to or cope with a given environment, to structural interventions, which aim to create an environment that exposes people to fewer risks and healthier options.

cAdapted from: Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol 1985;14:32-8.

NCHHSTP = National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

Rose was not primarily interested in explaining how we get sick, individually or collectively. His main point was that these two ways of thinking about health were linked to different strategies of intervention. Once again rephrasing, I depict in Figure 2's vertical axis the range of interventions, from individual (or agentic) interventions, which help people adapt to or cope with a given environment, to structural interventions, which aim to create an environment that exposes people to fewer risks and healthier options. The notion of agentic interventions helps avoid one of the confusion that springs up around the idea of structural interventions.10 The vertical axis is not precisely a spectrum of individual- to population-level interventions. Risk-reduction education, for example, is a classic tool of public health to help people avoid particular pathologies within an environment that is not going to change. A law requiring sodium warnings on labels may reach tens of millions of people with the same message. It is, however, essentially agentic, in that it depends upon the individual's response for its effect and it deals with risk factors that are generally proximal to a small number of specific outcomes, so it belongs in the lower right quadrant. (Of course, education may have a secondary, long-term environmental impact through changes in norms, so mandated education can creep up the axis toward structural intervention.) By contrast, a law that caps the amount of sodium allowed in a portion of prepared food would change the environment so that the agent is at least presented with different (and healthier) options.

In theory, efforts addressing social determinants should fit somewhere on the left side of Figure 2. For example, an intervention to help people better manage stress could be seen as an agentic intervention aimed at blunting a major mechanism of structural inequality and forestalling a wide range of negative individual health outcomes. The “sweet spot,” however, is the upper left quadrant. Actions that actually change pathological social conditions have enormous potential, if our theories are correct, to improve both the level and distribution of health, because they address fundamental causes that find expression in a wide range of ultimate health states reached via a plethora of pathways across the life course.11 Identifying measures that will do that is not only possible, it has been done. As Wilkinson and Pickett suggest, for example, there are two tried-and-true ways to address income inequality: limit pretax wage disparities or compensate with post-tax redistribution.12 In this country, we can take perverse encouragement from the fact that the contrary policies of the past 30 years have certainly been effective in making inequality worse.13

THE NCHHSTP WHITE PAPER

Placed in this framework, the NCHHSTP white paper2 and strategy exemplify an apparent, and often seen, contradiction: trying to address SDH by focusing on a handful of the pathologies in which social determinants are currently expressed. Even when the interventions are truly structural, they may be acting at points in the causal chain so remote from fundamental causes that the interventions cannot reduce overall health inequality, which simply finds a new path to the same inequitable results.11 Interventions aimed at the social determinants of particular diseases go up, but they don't go left.

The upper right quadrant can be a risky place for health equity. Structural interventions aimed at reducing a particular pathology across the population may inadvertently increase disparities because they do not sufficiently address fundamental causes.14 Uniformly raising the tax on cigarettes or alcohol does not have the same effect on all segments of the population, with differences that reflect the differential allocation of knowledge and other resources.15 We must also be conscious that the imperative to reduce specific pathologies, however logical, reflects personal and structural biases—research methods, funding systems, and career trajectories that are tied to and show impact on individual diseases.

These risks are real but can easily be overstated. For all the progress, our conception of social determinants and how they work remains a work in progress. The link between health and income inequality, for example, is complicated and nonlinear, a gross explanation for exquisitely fine relationships and processes.16,17 Rose's wise conclusion was, to put words in his mouth, that all the quadrants matter. We lack the knowledge to choose only to work in one or another, and it would be as wrong to put all our bets on the upper left as the lower right. NCHHSTP, adopting the prudent strategy of the World Health Organization's Commission on Social Determinants of Health, takes aim at social determinants directly, but will also work to improve the circumstances of daily life and continue to expand our knowledge base through research and evaluation.2,18

PHLR should be an important instrument of this strategy. NCHHSTP aims to pursue a “health-in-all-policies” approach, in which “all parts of government work toward common goals to achieve and reduce health inequities.”2 Like other interventions, policies enacted to improve health should be evaluated.19 The PHLR Program was created by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to increase the quantity and the quality of just these sorts of studies. For example, Kesselheim and Outterson have investigated whether patent laws designed to encourage pharmaceutical development actually promote antibiotic resistance by incentivizing pharmaceutical companies to overpromote antibiotics coming into the public domain.20 A health-in-all-policies approach also invites us to examine what we call “incidental health law”—policies that are not primarily focused on health, but may nonetheless be creating health benefits or harms. Program grantees at the Rand Corporation are studying the effects of zoning laws on violent crime, for example.

CONCLUSION

If law is all over, a health-in-all-policies approach is not enough to shed light on the place of law in a social determinants framework. We also need to be on the lookout for “law in all behaviors.” Health researchers have to let law out of its box in the macro-social context and start including legal variables and hypotheses on an equal footing with other social and attitudinal factors influencing health behavior. The NCHHSTP white paper mentions the need to review “HIV-specific criminal statutes to ensure that they are consistent with current knowledge of HIV transmission.”2 In PHLR, we would say we need to study how these laws and their enforcement interact with other factors to influence the behavior and attitudes of people with HIV—and, in fact, the PHLR Program is funding that research. But we can't do it alone. A law-in-all-behaviors approach means that there needs to be a greater willingness to include law within the zone of investigation across health research, even when law is not the primary focus of study. It also requires openness to a variety of research methodologies. Although quantitative methods may admit the inclusion of variables representing law on the books,21 qualitative methods are usually necessary to understand the extent to which, and the ways in which, law is implemented and enforced.22

Changing macro-social policies that contribute to inequality of all kinds may well be good for health. Health research can add to the case for macro-social policies that give every American a fair chance to thrive in the places they live, work, and play. There is unquestionably a need for more study of social determinants, their complex role in causing health outcomes, and the effectiveness of policy changes in addressing them. I have argued here, however, that we can also make progress by delineating the mechanisms or pathways along which structures are transformed into health outcomes.23 NCHHSTP's effort to find the social determinants in the pathways to HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome should be a model. PHLR can contribute by measuring the effects of laws and law enforcement practices.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks David Hoffman, Jennifer Ibrahim, Michelle Mello, Jeffrey Swanson, Alexander Wagenaar, and Jennifer Wood for their helpful comments.

Footnotes

The author's work was supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Worthman CM, Costello EJ. Tracking biocultural pathways in population health: the value of biomarkers. Ann Hum Biol. 2009;36:281–97. doi: 10.1080/03014460902832934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). Establishing a holistic framework to reduce inequities in HIV, viral hepatitis, STDs, and tuberculosis in the United States. Atlanta: CDC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1985;14:32–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/14.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarat A. “…The law is all over”: power, resistance and the legal consciousness of the welfare poor. Yale J L Human. 1990;2:343–79. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Stockholm (Sweden): Institute for Futures Studies; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burris S, Kawachi I, Sarat A. Integrating law and social epidemiology. J Law Med Ethics. 2002;30:510–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2002.tb00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Controlled Substances Act, 21 U.S.C. §§ 801 et seq.(2010)

- 8.Burris S, Blankenship KM, Donoghoe M, Sherman S, Vernick JS, Case P, et al. Addressing the “risk environment” for injection drug users: the mysterious case of the missing cop. Milbank Q. 2004;82:125–56. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burris S, Wagenaar AC, Swanson J, Ibrahim JK, Wood J, Mello MM. Making the case for laws that improve health: a framework for public health law research. Milbank Q. 2010;88:169–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00595.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLaren L, McIntyre L, Kirkpatrick S. Rose's population strategy of prevention need not increase social inequalities in health. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:372–7. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995 Spec No:80-94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkinson R, Pickett K. The spirit level: why greater equality makes societies stronger. New York: Bloomsbury Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh GK, Siahpush M. Widening socioeconomic inequalities in US life expectancy, 1980–2000. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:969–79. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: the inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:216–21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Remler DK. Poor smokers, poor quitters, and cigarette tax regressivity. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:225–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarlov AR. Public policy frameworks for improving population health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:281–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lynch J, Smith GD, Harper S, Hillemeier M, Ross N, Kaplan GA, et al. Is income inequality a determinant of population health? Part 1. A systematic review. Milbank Q. 2004;82:5–99. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. CSDH final report. Geneva: WHO; 2008. Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Exworthy M, Bindman A, Davies H, Washington AE. Evidence into policy and practice? Measuring the progress of U.S. and U.K. policies to tackle disparities and inequalities in U.S. and U.K. health and health care. Milbank Q. 2006;84:75–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2006.00439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kesselheim AS, Outterson K. Fighting antibiotic resistance: marrying new financial incentives to meeting public health goals. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1689–96. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tremper C, Thomas S, Wagenaar AC. Measuring law for evaluation research. Eval Rev. 2010;34:242–66. doi: 10.1177/0193841X10370018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mello MM, Powlowski M, Nañagas JM, Bossert T. The role of law in public health: the case of family planning in the Philippines. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:384–96. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burris S, Anderson ED. A framework convention on global health: social justice lite, or a light on social justice? J Law Med Ethics. 2010;38:580–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2010.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]