Abstract

Objectives

We used Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data to demonstrate a method for constructing a residential redlining index to measure institutional racism at the community level. We examined the application of the index to understand the social context of health inequities by applying the residential redlining index among a cohort of pregnant women in Philadelphia.

Methods

We used HMDA data from 1999–2004 to create residential redlining indices for each census tract in Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania. We linked the redlining indices to data from a pregnancy cohort study and the 2000 Census. We spatially mapped the levels of redlining for each census tract for this pregnancy cohort and tested the association between residential redlining and other community-level measures of segregation and individual health.

Results

From 1999–2004, loan applicants in Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, of black race/ethnicity were almost two times as likely to be denied a mortgage loan compared with applicants who were white (e.g., 1999 odds ratio [OR] = 2.00, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.63, 2.28; and 2004 OR=2.26, 95% CI 1.98, 2.58). The majority (77.5%) of the pregnancy cohort resided in redlined neighborhoods, and there were significant differences in residence in redlined areas by race/ethnicity (p<0.001). Among the pregnancy cohort, redlining was associated with residential segregation as measured by the percentage of black population (r=0.155), dissimilarity (r=0.250), exposure (r=–0.115), and isolation (r=0.174) indices.

Conclusions

The evidence of institutional racism may contribute to our understanding of health disparities. Residential redlining and mortgage discrimination against communities may be a major factor influencing neighborhood structure, composition, development, and wealth attainment. This residential redlining index as a measure for institutional racism can be applied in health research to understand the unique social and neighborhood contexts that contribute to health inequities.

Racial/ethnic inequities exist for a range of health-related factors and outcomes in the United States. Researchers have proposed that social and contextual factors are the fundamental causes of existing racial/ethnic health disparities.1–6 Neighborhood or community environments may play an important role in understanding the broader social context of health. In health research, the neighborhood or community context has been hypothesized to influence health both directly and indirectly through a variety of neighborhood conditions. These neighborhood conditions can potentially influence disparities in health outcomes through several pathways via exposure to stress or health-promoting environments at the individual and neighborhood level.7

Many studies have examined neighborhood-level constructs such as residential segregation and area-level socioeconomic characteristics as a key to understanding disparities in health.8–25 Prior health studies have operationalized residential segregation, or the racial/ethnic separation of groups geospatially, using measures such as the dissimilarity index and the percentage of black population in a specified area.8,14,15,25 Researchers postulate that racial residential segregation is a fundamental cause of disease differences between black and white people because it shapes social conditions for black people at the individual and community levels.13,25,26 Additionally, racial residential segregation may influence health beyond individual-level factors as a result of differential exposure to adverse neighborhood conditions due to systematic discrimination or institutional racism.6,7,25

Institutional racism consists of the policies, norms, and institutional practices that result in either intended or unintended differential access to resources and power based on race.27,28 The effects of institutional racism can result in a separation of racial groups (i.e., residential segregation), disinvestment in racially mixed or nonwhite communities, and directing investment and resources into homogenous, all-white communities.29 Forms of structural or institutional racism historically influenced health services, housing, education, employment, and attainment of wealth in the U.S.6,25,27,30,31

Residential redlining and other forms of mortgage discrimination are likely causes of residential segregation resulting in inequities in neighborhood environments and access to resources.32 Residential redlining, also known as mortgage lending discrimination, is the institutional practice in which banks and other financial institutions deny loans to communities and individuals based on race.6,33,34 The term was coined in the 1960s to describe the practice of lending institutions marking or drawing communities in red on maps as a means to deter lending and investment.34 Although the term was coined in the 1960s, these practices were in place prior to this time period and were supported by the federal government.29,34 Residential redlining has resulted in disparities in attaining a source of wealth through homeownership and disinvestment in communities as a result of these policies and practices.25,31

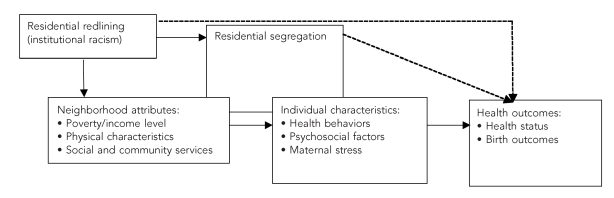

Residential redlining can be seen as one of the institutional policies and practices, both historically and currently, that has influenced neighborhood structures and environments by denying mortgage opportunities to individuals and communities of color. Residential redlining as a neighborhood factor may influence a neighborhood's composition or social environment through residential segregation, area-level socioeconomic status, or related attributes. These attributes may in turn influence health for populations, and residential redlining may directly influence health behaviors or health outcomes through various pathways. We present a conceptual model of the relationships among residential redlining, segregation, and pregnancy health (Figure 1). This conceptual model builds upon previous models examining neighborhood context and pregnancy health.7,8

Figure 1.

Conceptual modela of residential redlining, segregation, and pregnancy health

sThis figure is a conceptual model of the relationships among residential redlining, segregation, and pregnancy health. Residential redlining is a form of institutional racism that influences racially/ethnically segregated neighborhoods and other neighborhood attributes. These neighborhood factors may, in turn, directly influence pregnancy health or birth outcomes or indirectly influence them through stress or other individual characteristics.

Similar to residential segregation, residential redlining as a measure of institutional racism at the community level can be employed in health and social research to understand current health and social inequities. To our knowledge, only one published study has examined residential redlining in association with health.14 The study used data from the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA), which is a reporting mechanism for determining housing needs in communities, distributing investments for development, and identifying discriminatory lending practices.14,26,35 The researcher created a measure for residential redlining by applying a fixed-effects model to estimate the odds of loan denial among Chinese Americans for each neighborhood.14

To our knowledge, no other studies have investigated mortgage discrimination at the community level against black people or other racial/ethnic minority groups as a proxy of institutional racism in relation to health. In addition, this study has applied a multilevel model (i.e., random effects model) in constructing an index for residential redlining at the community level. Finally, we argue that residential redlining and the use of HMDA data capture an important dimension of the neighborhood context as a social determinant of health largely overlooked in prior work.

To address these current research gaps, we demonstrate the application of HMDA data and a method of constructing a residential redlining index for public health applications. We linked these data to a cohort study of pregnant women to enhance the public health application of administrative data such as HMDA. Linkage to the pregnancy cohort provides an example of its usage in a perinatal health context, which can be applied to other health cohorts. This linkage allowed us to examine contextual layering by studying multilevel effects and interrelationships between neighborhood-level and individual-level information. In this study, we (1) outline a method for developing and interpreting a residential redlining index using HMDA data, (2) spatially map the levels of redlining of neighborhoods among a pregnancy cohort in Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, (3) examine the redlining index in association with four measures for residential segregation and individual risk factors among a pregnancy cohort, and (4) describe how this index can be applied to improve the study of public health issues.

METHODS

Data sources

The HMDA is an administrative database created by the Federal Reserve Board that collects yearly information from banks and other lending institutions providing mortgage loans. We accessed these data through the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council's (FFIEC's) HMDA Loan Application Register. Aggregate reports for HMDA are available online and on CD-ROM. For this study, we used individual loan information rather than aggregated data, which are also now available online through the FFIEC. The residential redlining construct for this study was derived from the HMDA for the years 1999–2004.35

The HMDA dataset contains mortgage loan information from financial institutions throughout the U.S. and includes information about type and amount of loan, census tract of the property, loan disposition, and characteristics of the applicant. This study excluded (1) incomplete applications that were not processed by lending institutions and, therefore, could not be part of a measure for loan disposition bias; (2) properties that are not owner-occupied; (3) home improvement loans; and (4) multifamily units.14 This analysis only included mortgage loans with information about the applicant's race and only those identified as black or white race. Although other racial/ethnic minority groups are included in this dataset, we decided to examine only the black-white disparity in loan disposition as an example and application for understanding mortgage discrimination. The HMDA database included an average of 16,527 loans per year from 1999–2004 for this analytic sample in Philadelphia County.

We linked indices for residential redlining (from HMDA) and segregation (from the 2000 Census) to each census tract in Philadelphia County where women from a pregnancy cohort study resided. The pregnancy cohort study was a cross-sectional, clinical prevalence study of chronic maternal stress and bacterial vaginosis (BV). Additional details about the study have been reported elsewhere.36,37

The women were enrolled during their first prenatal care visit at community-based and hospital-based clinics. Inclusion criteria for the study were singleton gestation, less than 20 weeks gestation, intrauterine pregnancy, and English- or Spanish-speaking. Female interviewers conducted a baseline survey and included information about the women's individual health, reports of stress and discrimination, demographic information, the census tracts in which they lived, and when the survey was collected. The survey information was linked with their vital birth record information after the women gave birth. A total of 4,880 pregnant women completed the survey. Of these women, we were able to successfully match 4,104 (84% of the 4,880) to the birth file and successfully geocode their addresses.

Neighborhood definition

The smallest neighborhood unit included in the HMDA database is the census tract, although block group-level data are available from the U.S. Census and for the pregnancy cohort. As a result, the definition of neighborhood for this study was the census tract within Philadelphia County. The addresses of the pregnant women were geocoded and assigned a census tract based on the 2000 Census boundaries.

Measures for deriving the redlining index

We used the HMDA dataset to derive the redlining indices for each census tract in Philadelphia County.

Outcome for the redlining index.

The loan action taken, which describes whether a loan was accepted or denied by a financial institution, was used to create the redlining measure.

Main predictor for redlining index.

The race of the loan applicant was the main predictor of loan disposition used in this study. The redlining index was operationalized as the black-white difference in loan disposition and, hence, included those who identified themselves as black or white race. Loans that were missing information about the applicant's race were not included in the analysis. Race data were missing either because the race was not provided by the applicant or loan officer, or because the applicant's race was not applicable if a financial institution rather than an individual purchased the loan.

Covariates for the redlining index.

These covariates included the applicant's gender and gross annual income, as well as the loan amount. These covariates were chosen based on conceptual models and previous studies utilizing HMDA data to report housing discrimination.14,33,38,39 The applicant's gross annual income and the loan amount were reported in thousands of dollars and were continuous variables. Other important data, such as the applicant's credit score and employment status, were not available in the HMDA database so could not be included as covariates. Other neighborhood-level attributes were not included as covariates, although they may be related to loan disposition. In this study, we were interested in understanding the black-white difference in loan disposition (i.e., redlining) as a neighborhood-level factor alone and then examining its association with other neighborhood-level factors such as residential segregation.

Method for deriving the redlining index

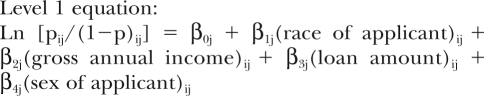

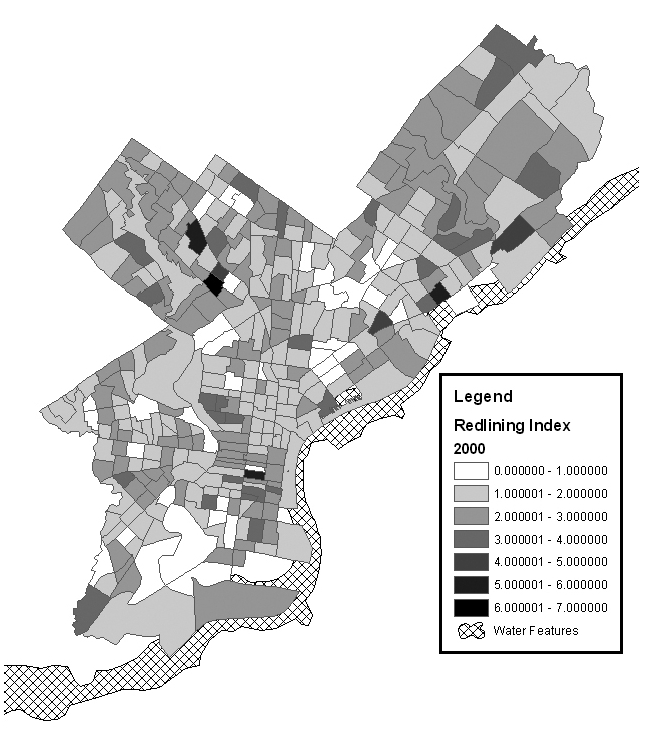

We calculated the indices using multilevel logistic models to account for clustering of individual loans within census tracts and to create an estimate for each census tract. The estimates produced from the models allowed us to estimate the black-white odds of loan denial as a function of other covariates, which was the redlining index for this study. The full model was as follows:

Level 1 equation:

|

Level 2 equation:

|

where i is an index for individuals within census tracts and j is an index for census tracts.

The outcome to be examined was the natural log odds of being denied a loan (p, probability of event) where u0j is the random effect for census tract j. We also included a random effect for the intercept and slope for race. The random effect for race allowed us to estimate the black-white difference for each census tract. We assumed the random effects for the intercept and slope were normally distributed with means of zero, variance of τ00 for the intercept and τ11 for the slope, and a covariance between the intercept and slope of τ10.

The final index placed each census tract along a continuum of mortgage loan discrimination (i.e., residential redlining). For example, a score of 2.0 indicated a neighborhood where the odds of loan denial among black people were twice the odds of loan denial among white people after controlling for loan amount, income, and gender of the applicant. Previous studies categorized the redlining index at the point where minority loan applicants were disfavored by 40% compared with white applicants, calculated as an odds ratio (OR) of 1.4.5,14,40 For reporting purposes, indices with a threshold of 1.4 are presented along with the continuous measure for the redlining index. The redlining indices for the census tracts in Philadelphia County were compared across years to see if there were any significant mean changes in redlining between 1999 and 2004. Because there were changes in the mean redlining index during the six-year period, the final redlining index was chosen based on the year in which the pregnant woman entered the cohort study. This index was linked to the census tract in which she lived. We used the GLIMMIX Procedure in SAS® version 9.2 to create the redlining indices.41

Additional measures from the U.S. Census and pregnancy cohort

Neighborhood-level measures.

We derived the following measures from the 2000 Census. First, we applied several indices for residential segregation; additional details and calculations for these indices are described elsewhere.42 We linked the segregation measures to the census tracts from the geocoded addresses of the pregnant women from the cohort study. The “percentage black” indicates the percentage of black residents for a census tract. The “index of dissimilarity” is a measure of residential segregation that quantifies the proportion of black people who would have to change their area of residence to achieve an even distribution of the population in census tracts. This index measures the level of evenness or differential distribution of groups across geographic units. The “exposure index,” also known as the interaction index, ranges from 0 to 1 and measures the extent to which members of a minority group (e.g., black people) are exposed to members of a majority group (e.g., white people).42 The “isolation index,” another measure of exposure, varies from 0 to 1 and describes the extent to which members of minority group X are only exposed to one another.

All of these indices range from 0 to 1, and the higher values indicate a greater degree of segregation. Both the exposure index (i.e., the interaction index) and isolation index differ from measuring evenness (i.e., the index of dissimilarity) in that both interaction and isolation attempt to measure the experiences of segregation felt by the average minority or majority member. For example, a minority group may be evenly distributed throughout a city but may have limited exposure to a majority group if the minority group comprises a larger proportion of that city. The exposure indices (i.e., interaction and isolation) take into account the size of each group in determining the degree of segregation between them.42

Individual-level measures.

We derived the following measures from the pregnancy cohort study. For maternal race/ethnicity, participants were asked to identify their race, which also included an option of Hispanic ethnicity. The classifications included in this study were non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic/Latina, or other race/ethnicity. Women from various Asian races/ethnicities comprised the “other” category, which was less than 3% of the population.

Total household income was operationalized as income from jobs, public assistance, unemployment, Supplemental Security Income, family or friends, or other sources. This was a categorical variable where respondents chose an income range that best fit their circumstances. Maternal education was categorized as less than high school, high school/general equivalency diploma, or post-high school. Respondents were also asked if they used tobacco or alcohol during pregnancy.

BV was diagnosed by evaluation of Gram-stained vaginal fluid samples, using Nugent's method.37 A score of 0 to 10 was assigned, and BV status was defined as positive (score of 7 to 10), intermediate (score of 4 to 5), or negative (score of 0 to 3). General health status was measured by asking participants, “Thinking back to the year just before this pregnancy, would you say your health was excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?”

Perceived stress was measured using a 14-item self-report Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (CPSS), which measures the degree to which a respondent appraises stressful circumstances along dimensions of unpredictability, uncontrollability, and overload.43,44 Examples of items in this scale include, “You have felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life,” “You have felt nervous or stressed,” and “You have felt that you were on top of things.” Participants answered based on a Likert scale of 0 to 4 regarding the degree to which the item related to them in the past month (0 = never, 1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = fairly often, or 4 = very often). A total CPSS score was computed by summing across all items. The scores ranged from 0 to 51. This scale is recommended for examining the role of appraised stress in the etiology of disease.44 The CPSS has good internal reliability and fair test-retest reliability among college and community samples as well as samples of pregnant women36,37,43 (sample Cronbach's alpha = 0.81). The final scores were categorized as greater than or less than/equal to the median score of 24.

Statistical analyses

Univariate analyses were conducted to assess the distribution and frequency of redlining and residential segregation for the overall pregnancy cohort and by race/ethnicity. Bivariate associations were also assessed between the redlining and segregation and between redlining and other individual characteristics. We used SAS version 9.2 for the statistical analyses.41

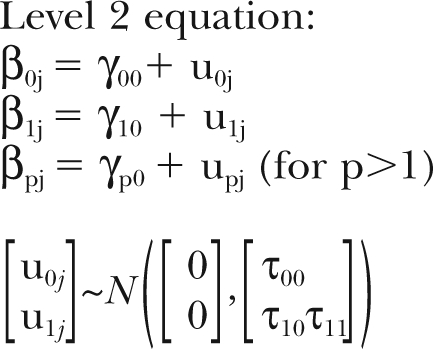

GIS mapping

We used ArcGIS® version 9.3 to create a color-coded map of the levels of residential redlining for each census tract in Philadelphia County.45 We created maps for the years 1999–2004; however, only the map for the year 2000 is included in this article.

The secondary analysis was approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Nursing-Public Health Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Figure 2 is a map of residential redlining across the various census tracts in Philadelphia County during the year 2000. Center City and Lower North Philadelphia are characterized by having low levels of redlining with the lighter shades toward the middle of the map. There are a few pockets of the highest levels of redlining throughout Philadelphia, with the regions of Far Northeast Philadelphia also having neighborhoods with redlined indices greater than 3.0. The aforementioned neighborhoods are based on Philadelphia's Planning Analysis Sections.46

Figure 2.

Map of residential redlining in Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania: HMDA data, 2000a

aThis figure shows a map of the level/amount of residential redlining for each census tract in Philadelphia County in 2000. The redlining indices are calculated as the odds ratios for the black-white difference in mortgage loan denials after controlling for income, loan amount, type of loan, and gender of applicant. The HMDA data were used to calculate the redlining indices.

HMDA = Home Mortgage Disclosure Act

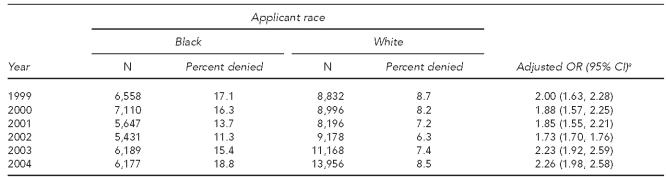

In developing the index of residential redlining, we explored the basic characteristics of the mortgage loans included in HMDA. The percentage of mortgage loans denied ranged from 8.0% to 12.1% among the entire Philadelphia County population from 1999–2004 (data not shown). We also evaluated the crude relationship between race and loan disposition among loan applicants in Philadelphia County (Table 1). Based on the crude associations, we found that the average black applicant was more likely to be denied a loan compared with a white applicant for all six years (e.g., 1999 OR=2.16, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.96, 2.39; and 2004 OR=2.51, 95% CI 2.30, 2.74) (data not shown). When controlling for the loan amount and the applicant's income and gender, we still found a slight elevation in the odds of denial among black applicants compared with white applicants (e.g., 1999 OR=2.00, 95% CI 1.63, 2.28; and 2004 OR=2.26, 95% CI 1.98, 2.58) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Racial differences in mortgage loan denials in Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania: HMDA data, 1999–2004

aAdjusted for loan amount, income, and gender of the applicant

HMDA = Home Mortgage Disclosure Act

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

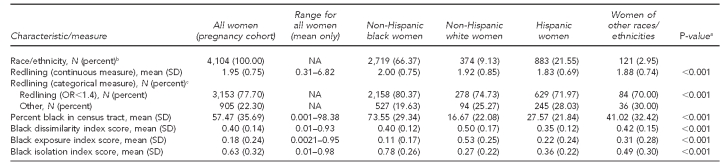

Table 2 includes residential redlining indices and neighborhood characteristics for the entire pregnancy cohort and by race/ethnicity. The majority of the pregnant women were non-Hispanic black followed by Latina/Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, and other racial/ethnic minority groups. The majority of the pregnancy cohort (77.7%) lived in redlined areas. The redlining indices ranged from 0.31 to 6.82 among the cohort (Table 2). Non-Hispanic black women were more likely to live in redlined neighborhoods compared with women of other racial/ethnic groups (p<0.001). The mean scores were 2.00 for non-Hispanic black, 1.92 for non-Hispanic white, 1.83 for Latina/Hispanic, and 1.88 for women of other racial/ethnic minority groups. Non-Hispanic black women were also more likely to live in segregated neighborhoods compared with women of other racial/ethnic groups (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Residential redlining and segregation among the pregnant population, Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, 1999–2004

aComparison of mean values across racial/ethnic groups

bSeven respondents were missing race information.

cForty-six respondents were missing information on redlining.

SD = standard deviation

OR = odds ratio

NA = not applicable

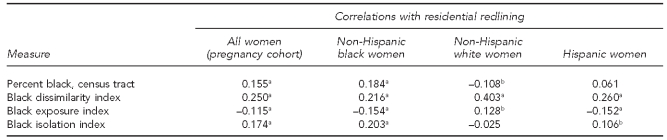

Among the neighborhoods where the overall pregnancy cohort lived, residential redlining was positively associated with the percentage black, black dissimiliarity, and black isolation at the census tract level (r=0.155, r=0.250, and r=0.174 respectively) (Table 3). Residential redlining was negatively associated with the black exposure segregation index (r= –0.115). These same relationships held among the neighborhoods where the participants who were non-Hispanic black and Hispanic lived (results not shown). However, among the neighborhoods where the non-Hispanic white participants lived, residential redlining was positively associated with the dissimilarity and exposure indices (r=0.403 and r=0.128, respectively) but negatively associated with the percentage black and isolation index (r= –0.108 and r= –0.025, respectively).

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients of residential redlining and segregation for the pregnant population, Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, 1999–2004

ap<0.001

bp<0.05

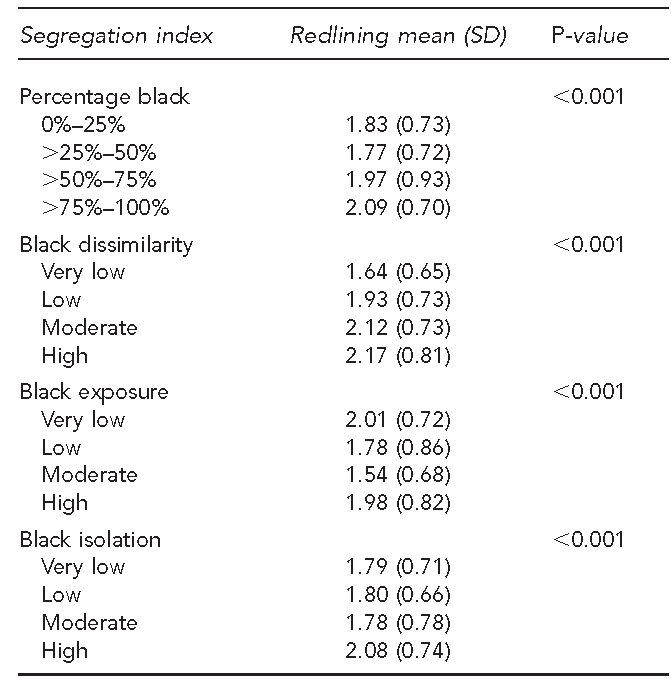

We also examined the relationship between redlining and the various segregation measures by determining the mean redlining index for each level of segregation (Table 4). We found some general trends where there was a positive and significant association between redlining and segregation as measured by percentage black, black dissimilarity, and black isolation. However, the mean redlining scores were highest among very low and high black exposure.

Table 4.

Redlining scores by level of segregation for the pregnant population, Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, 1999–2004

SD = standard deviation

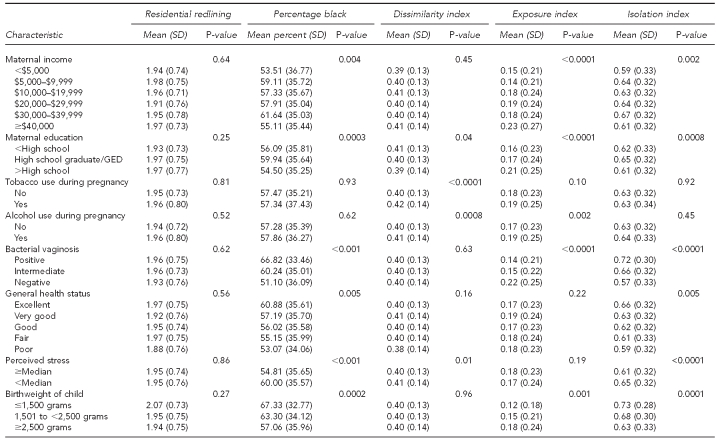

Finally, we examined residential redlining and segregation in relation to various individual-level risk factors and health outcomes among the pregnancy cohort (Table 5). We found no significant relationships between residential redlining and the individual pregnancy-related factors. However, we found some significant associations between some of the segregation measures and the pregnancy-related factors. Percentage black was significantly associated with maternal income and education, but there was no linear trend. Tobacco use and alcohol use during pregnancy were positively associated with dissimilarity (p<0.0001 and p<0.001, respectively), although the differences were slight. BV was positively associated with percentage black (p<0.001) and isolation (p<0.0001), but negatively associated with exposure (p<0.0001). General health status was positively associated with percentage black and isolation (both p=0.005), and perceived stress was negatively associated with percentage black (p<0.001) and isolation (p<0.0001). Finally, low birthweight was positively associated with percentage black (p<0.001) and isolation (p=0.0001), but negatively associated with exposure (p=0.001).

Table 5.

Residential redlining and segregation for pregnancy-related factors, Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, 1999–2004

SD = standard deviation

GED = general equivalency diploma

DISCUSSION

Traditional risk factors alone do not explain all of the excess perinatal risk experienced by African American women. Racism should be studied as it is a unique exposure for African Americans and can potentially explain the disparity. However, few measures of institutional racism are used in perinatal health research or public health research in general. In this article, we demonstrated the use of the HMDA dataset to create a community-level index for residential redlining to capture the effects of intuitional racism. We demonstrated a method for improving the contextual analysis of institutional racism by developing and applying a redlining index at the community level and illustrated its application in a population of pregnant women in Philadelphia. The multilevel model we applied to create the index allowed us to strengthen our census tract-specific estimates for redlining by also optimizing information across census tracts in Philadelphia County.47 Similar to the use of the U.S. Census in creating community-level measures such as residential segregation, economic deprivation, and neighborhood deprivation, using HMDA data to create indices for residential redlining can provide neighborhood contextual information important for understanding the social determinants of health inequities.6,14,26,48–50

The residential redlining measure provides contextual information about mortgage and housing discrimination among various communities that is not captured in other measures such as residential -segregation. Residential segregation can have either a positive or negative influence on health, producing an environment that may be inequitable and stress-inducing or an environment where people choose to live for protective reasons (e.g., ethnic enclaves). In contrast, residential redlining limits choices and forces people to live in neighborhoods that may not have been in their best interest, as it was not their choice. Redlining may have a more negative association. These neighborhoods may be more likely to be underserved or stress-inducing. Additionally, the residential redlining measure can provide additional information about neighborhood structure, opportunities, and development when taken into consideration with other neighborhood measures.

Among mortgage applicants in Philadelphia County included in the HMDA database between 1999 and 2004, black applicants were more likely to be denied a mortgage loan compared with white applicants. When applying the redlining index to the neighborhoods where the pregnancy cohort participants lived, we found that the pregnant women were more likely to live in redlined neighborhoods. This means that on average, the participants in the pregnancy cohort study lived in neighborhoods where black people were twice as likely as white people to be denied a mortgage loan. We also found that non-Hispanic black women from the pregnancy cohort were more likely to live in redlined neighborhoods compared with women of other racial/ethnic groups. The possible reasons for this effect are that non-Hispanic black people, and black communities in general, have been historically subject to discrimination in housing and the mortgage industry.8,26,32,33,51,52

We also found that residential redlining was associated with residential segregation and percentage black among the neighborhoods in which the pregnancy cohort lived. Redlining was also associated with a greater percentage black on the census-tract level among the pregnancy cohort. Although these neighborhood-level constructs were associated, their correlations were small. This finding suggests that the residential redlining index included in this study may be capturing a separate construct from the segregation measures. As a result, redlining may be a broader construct of institutional racism than segregation.

We did not find a significant association between redlining and the pregnancy-related outcomes. There may be several reasons for this lack of association. First, residential redlining is an institutional practice and upstream factor that has historically and currently influenced other neighborhood factors such as segregation. Because of this historical influence, we may not empirically be able to see a direct effect of residential redlining on pregnancy-related outcomes. Second, there was insufficient variation in residential redlining at the neighborhood level among the pregnancy cohort and for various racial/ethnic groups within the cohort. This lack of variation may also have influenced our ability to estimate associations between redlining and health. Additionally, there may be important unmeasured mediators in the relationship between redlining and pregnancy outcomes, thus influencing this association.

One previous study examining residential redlining and health among Chinese Americans did find a significant association.14 We did not examine the redlining-pregnancy outcome relationship for each racial/ethnic group separately. Some studies examining neighborhood context and health argue that these relationships may differ by racial/ethnic group. However, we did find significant associations with some of the segregation measures and pregnancy-related outcomes. Other studies have shown that segregation increases pregnancy-related risks, and we hypothesized a similar relationship for residential redlining.8,9,15,18,53 Residential segregation has been suggested as the “cornerstone” on which racial/ethnic inequities have been built, and residential redlining has been noted as a major contributor to existing residential segregation.25,29,54

Limitations

Using the HMDA as a means to measure residential redlining does have a few limitations. HMDA does not include information about an applicant's employment status, debt-to-income ratio, or credit scores, which are important factors in measuring and understanding loan disposition.52 Some of these factors could have an effect on the actual redlining constructs developed in this study, but could not be directly measured during the years in which this study took place (1999–2004).

Another general challenge in applying neighborhood constructs in health research is the use of administrative units, such as census tracts, to define neighborhoods. The smallest unit of analysis included in the HMDA database is the census tract; hence, this administrative cluster drives data analysis. However, researchers investigating the neighborhood context in relation to children's health and perinatal health have concluded that using smaller block group administrative units vs. census tracts yielded similar results, although use of larger units such as ZIP codes becomes more problematic.55,56

Missing race data in the HMDA may also pose a challenge. After applying specific exclusion criteria for the HMDA analytic sample, approximately 15% of the loans were missing data for race for 1999. Using data from 1993–1999, one study found that race data were missing for systematic reasons and that applications from black and Hispanic people may be more likely to be without race data than applications from white people, suggesting that denial rate disparities may actually be underestimated.57

Strengths

This study had multiple strengths that constitute wider usage of the HMDA data to capture residential redlining for health research. The HMDA data provide annual information on mortgage lending and include applicant characteristics such as race, gender, and income. This data source is useful in measuring racial, income, and gender disparities in mortgage lending for overall populations and for specific regions. In this study, we applied multilevel modeling techniques to calculate region-specific estimates of residential redlining based on race. We were also able to acquire estimates for residential redlining over a six-year period using cross-sectional data from 1999–2004, rather than only one year, thereby strengthening the methods applied in a previous study. Although lending disposition is a complex phenomenon influenced by multiple factors, these data provide additional information in relation to mortgage lending and housing as social determinants of health. Neighborhoods that are characterized as redlined may be important in understanding racial/ethnic health inequities and the social context in which pregnant women, and other populations in general, live.55

Finally, the HMDA dataset is a public administrative database that is useful for monitoring and measuring mortgage lending.58 These HMDA data are now available online in a downloadable format that includes individual loan information for all loans in the U.S. for a given year. This is a public access database, similar to the U.S. Census, which could be applied to future health studies in an effort to understand a form of institutional racism as a contributor to existing health inequities.

CONCLUSIONS

The HMDA dataset provides a means to measure residential redlining and may provide insight into upstream factors contributing to racial/ethnic inequities in health and other outcomes. Racially/ethnically segregated neighborhoods could be a direct result of institutional discriminatory practices such as redlining or a result of the choices of individuals selecting places to live. Redlining, however, is not a choice but a practice imposed disproportionately upon black communities and other communities of color, thus having the possibility of a negative effect on health, unlike other segregation measures.

The redlining index allows researchers to apply an institutional measure in an effort to examine social and contextual factors in conjunction with individual factors. This index can be constructed for neighborhoods (i.e., census tracts) throughout the U.S. and applied to a variety of health studies examining the neighborhood and social context. Additionally, this residential redlining index provides a new measure that differs from measures for residential segregation used in other health studies. Moreover, the HMDA database and methods presented in this study provide an avenue for multidisciplinary research and work in the areas of housing and public health. Future studies could utilize the HMDA database and incorporate this contemporary measure of residential redlining to elucidate the influence of individual factors and upstream policies (current and historical) on various health outcomes, with the goal of eliminating health-related inequities.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the following individuals for their contributions to this research: Jon Hussey, Daniel Bauer, and Stephen Marshall for their theoretical and methodological contributions; the late Jim Ovitt for assisting with Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data retrieval; Leny Matthews for assisting with data retrieval and statistical consulting; Amanda Henley for geographic information systems consulting; and Gilbert Gee for his insight.

Footnotes

Funding for this research was provided in part by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Predoctoral National Research Service Award and the Health Resources and Services Administration Maternal and Child Health Epidemiology Training Grant.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agencies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995 Spec No:80-94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Link BG, Phelan JC. McKeown and the idea that social conditions are fundamental causes of disease. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:730–2. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogan VK, Njoroge T, Durant TM, Ferre CD. Eliminating disparities in perinatal outcomes—lessons learned. Matern Child Health J. 2001;5:135–40. doi: 10.1023/a:1011357317528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blank RM. An overview of trends in social and economic well-being, by race. In: Smelser NJ, Wilson WJ, Mitchell F, editors. America becoming: racial trends and their consequences. Washington: National Academy Press; 2001. pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jargowsky PA. Poverty and place: ghettos, barrios and the American city. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Massey D, Denton NA. American apartheid: segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Culhane JF, Elo IT. Neighborhood context and reproductive health. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5 Suppl):S22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell JF, Zimmerman FJ, Almgren GR, Mayer JD, Huebner CE. Birth outcomes among urban African-American women: a multilevel analysis of the role of racial residential segregation. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:3030–45. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell JF, Zimmerman FJ, Mayer JD, Almgren GR, Huebner CE. Associations between residential segregation and smoking during pregnancy among urban African-American women. J Urban Health. 2007;84:372–88. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9152-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1783–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elo IT, Mykyta L, Margolis R, Culhane JF. Perceptions of neighborhood disorder: the role of individual and neighborhood characteristics. Soc Sci Q. 2009;90:1298–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang J, Madhavan S, Alderman MH. Low birth weight: race and maternal nativity—impact of community income. Pediatrics. 1999;103:E5. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acevedo-Garcia D, Lochner KA. Residential segregation and health. In: Kawachi I, Berkman LF, editors. Neighborhoods and health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 265–87. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gee GC. A multilevel analysis of the relationship between institutional and individual racial discrimination and health status. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:615–23. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grady SC. Racial disparities in low birthweight and the contribution of residential segregation: a multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:3013–29. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inagami S, Borrell LN, Wong MD, Fang J, Shapiro MF, Asch SM. Residential segregation and Latino, black and white mortality in New York City. J Urban Health. 2006;83:406–20. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9035-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laraia B, Messer L, Evenson K, Kaufman JS. Neighborhood factors associated with physical activity and adequacy of weight gain during pregnancy. J Urban Health. 2007;84:793–806. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9217-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mason SM, Messer LC, Laraia BA, Mendola P. Segregation and preterm birth: the effects of neighborhood racial composition in North Carolina. Health Place. 2009;15:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Messer LC, Buescher PA, Laraia BA, Kaufman JS. Neighborhood-level characteristics as predictors of preterm birth: examples from Wake County, North Carolina. [cited 2011 Apr 14];North Carolina State Center for Health Statistics Studies November 2005. 148:1–9. Also available from: URL: http://www.epi.state.nc.us/SCHS/pdf/SCHS148.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Messer LC, Kaufman JS, Dole N, Savitz DA, Laraia BA. Neighborhood crime, deprivation, and preterm birth. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:455–62. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Campo P, Burke JG, Culhane J, Elo IT, Eyster J, Holzman C, et al. Neighborhood deprivation and preterm birth among non-Hispanic black and white women in eight geographic areas in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:155–63. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearl M, Braveman P, Abrams B. The relationship of neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics to birthweight among 5 ethnic groups in California. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1808–14. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pickett KE, Collins JW, Jr, Masi CM, Wilkinson RG. The effects of racial density and income incongruity on pregnancy outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:2229–38. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickett KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55:111–22. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:404–16. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Massey DS. Residential segregation and neighborhood conditions in U.S. metropolitan areas. In: Smelser NJ, Wilson WJ, Mitchell F, editors. America becoming: racial trends and their consequences. Washington: National Academy Press; 2000. pp. 391–434. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener's tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1212–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKenzie K, Bhui K. Institutional racism in mental health care. BMJ. 2007;334:649–50. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39163.395972.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gotham KF. Racialization and the state: the Housing Act of 1934 and the creation of the Federal Housing Administration. Soc Perspect. 2000;43:291–317. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Semmes CE. Racism, health, and post-industrialism: a theory of African-American health. Westport (CT): Praeger Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satter B. Family properties: race, real estate, and the exploitation of black urban America. New York: Henry Holt and Company; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charles CZ. The dynamics of racial residential segregation. Annu Rev Sociol. 2003;29:167–207. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Courchane MJ, Zorn PM. Dawning of a new age: examinination for discrimination in lending. Banking and Financial Services Policy Rep. 2008;27:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hillier AE. Redlining and the home owners' loan corporation. J Urban History. 2003;29:394–420. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council. Home Mortgage Disclosure Act. [cited 2011 Apr 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.ffiec.gov/hmda.

- 36.Culhane JF, Rauh V, McCollum KF, Elo IT, Hogan V. Exposure to chronic stress and ethnic differences in rates of bacterial vaginosis among pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1272–6. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.127311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Culhane JF, Rauh V, McCollum KF, Hogan VK, Agnew K, Wadhwa PD. Maternal stress is associated with bacterial vaginosis in human pregnancy. Matern Child Health J. 2001;5:127–34. doi: 10.1023/a:1011305300690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hutchinson PM, Ostas JR, Reed JD. A survey and comparison of redlining influences in urban mortgage lending markets. Real Estate Economics. J Am Real Estate Urban Economics Assoc. 1977;5:463–72. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahlbrandt RS. Exploratory research on the redlining phenomenon. Real Estate Economics: J Am Real Estate Urban Economics Assoc. 1977;5:473–81. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siefert K, Bowman PJ, Heflin CM, Danziger S, Williams DR. Social and environmental predictors of maternal depression in current and recent welfare recipients. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:510–22. doi: 10.1037/h0087688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS®: Version 9.2 for Windows. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Massey DS, Denton NA. The dimensions of residential segregation. Social Forces. 1988;67:281–315. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Baum A. Socioeconomic status is associated with stress hormones. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:414–20. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221236.37158.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.ESRI. ArcGIS®: Version 9.3. Redlands (CA): ESRI; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Philadelphia Department of Public Health, Division of Maternal, Child and Family Health. MCFH data annual, 2009. [cited 2011 Apr 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.phila.gov/health/pdfs/MCFHDataWatch_2009.pdf.

- 47.Kaufman JS, Dole N, Savitz DA, Herring AH. Modeling community-level effects on preterm birth. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:377–84. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(02)00480-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Messer LC, Laraia BA, Kaufman JS, Eyster J, Holzman C, Culhane J, et al. The development of a standardized neighborhood deprivation index. J Urban Health. 2006;83:1041–62. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9094-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Messer LC, Kaufman JS. Using Census data to approximate neighborhood effects. In: Oakes JM, Kaufman JS, editors. Methods in social epidemiology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2006. pp. 209–36. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zierler S, Krieger N, Tang Y, Coady W, Siegfried E, DeMaria A, et al. Economic deprivation and AIDS incidence in Massachusetts. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1064–73. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fernandez M. Study finds disparities in mortgages by race. The New York Times. 2007 Oct 15; [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turner MA, Skidmore F, editors. Mortgage lending discrimination: a review of existing evidence. Washington: The Urban Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Osypuk TL, Acevedo-Garcia D. Are racial disparities in preterm birth larger in hypersegregated areas? Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:1295–304. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glaeser EL, Vigdor JL. Racial segregation in the 2000 Census: promising news. Washington: The Brookings Institution Survey Series, Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy; 2001. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- 55.Culhane JF, Elo IT. Neighborhood context and reproductive health. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5 Suppl):S22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV, Carson R. Geocoding and monitoring of US socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and cancer incidence: does the choice of area-based measure and geographic level matter? The Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:471–82. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dietrich J Department of the Treasury, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (US). Missing race data in the HMDA and the implications for the monitoring of fair lending compliance. Economic and Policy Analysis Working Paper 2001-1. Washington: Department of the Treasury, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency; 2001. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- 58.Munnell AH, Browne LE, McEneaney J, Tootell GMB. Mortgage lending in Boston: interpreting HDMA data. Working Paper 92-7. Boston: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston; 1992. [Google Scholar]