Abstract

Dengue is an expanding arboviral disease of variable severity characterized by the emergence of virus strains with greater fitness, epidemic potential and possibly virulence. To investigate the role of dengue virus (DENV) strain variation on epidemic activity we studied DENV-2 viruses from a series of South Pacific islands experiencing outbreaks of varying intensity and clinical severity. Initially appearing in 1971 in Tahiti and Fiji, the virus was responsible for subsequent epidemics in American Samoa, New Caledonia and Niue Island in 1972, reaching Tonga in 1973 where there was near-silent transmission for over a year. Based on whole-genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis on 20 virus isolates, Tonga viruses were genetically unique, clustering in a single clade. Substitutions in the pre-membrane (prM) and nonstructural genes NS2A and NS4A correlated with the attenuation of the Tongan viruses and suggest that genetic change may play a significant role in dengue epidemic severity.

Keywords: Dengue, evolution, Flavivirus, South Pacific, phylogeny, molecular epidemiology, viral genotype, strain variation, lineage, epidemic attenuation

INTRODUCTION

Dengue is an arboviral infectious disease transmitted by anthropophilic Aedes mosquitoes, primarily Ae. aegypti, which typically breed in water-holding containers within human habitations (Rodhain and Rosen 1997). The dengue virus (DENV), a 11 kb positive-sense, single-strand RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae, has four closely related but antigenically distinct serotypes (DENV-1 to -4), none of which provide long lasting cross-protective immunity to the other serotypes. Infection with any one of the four serotypes can be asymptomatic or produce a spectrum of clinical symptoms from non-specific febrile illness, dengue fever (DF), to the more severe dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS). While dengue disease incidence has risen at an alarming rate over the last few decades to where it now accounts for 50–100 million infections annually worldwide (WHO 1997), the mechanism(s) by which DENV causes disease remain(s) unclear and no antiviral therapy or vaccine is yet available. Nonetheless, various risk factors for DHF/DSS have been identified, including viral strain, vector competency, age and genetic background of the host, and secondary infection by a heterologous DENV serotype (Gubler 1988, 1998; Halstead 2007). The major question in DENV research is understanding how these factors conspire to cause such large variation in disease and epidemic intensity. Here we take advantage of a natural experiment in which many, if not most, of the confounding factors in dengue disease dynamics could be excluded except for virus evolution, thus allowing for a clearer examination of the effects of strain variation and genetic change on dengue virus epidemic severity. We conducted whole-genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of DENV-2 collected during a series of outbreaks amongst similarly naive host populations in order to determine whether an apparent attenuation in the ultimate transmission event correlated with genetic change in the virus. Thus, this study offers an opportunity to isolate the effects of virus genetic variation from seropositivity rates on epidemic behavior.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Our study derives from epidemiological, clinical and virologic observations on a series of outbreaks of dengue type-2 virus (DENV-2) in the South Pacific from 1971 – 1974, which were notable for abruptly shifting from a distinctly virulent character to one that was quite attenuated (Gubler et al. 1978, 1997). Following a major regional pandemic of DENV-1 that affected most islands from 1942 to 1945, dengue was absent from the Pacific for almost 30 years (Gubler 1997) aside from small outbreaks of DENV-3 in Tahiti in 1964 and 1969 (Laigret et al. 1967, Saugrain et al. 1970). However, in early 1971 DENV-2 appeared almost simultaneously among populations that were largely immunologically naive on Fiji and Tahiti (Moreau et al. 1973, Maguire et al. 1974, Rosen 1977), then spread to New Caledonia, Niue and Samoa in 1972 (Loison et al. 1973, Barnes and Rosen 1974, Rosen 1977), followed by Tonga in late 1973 (Gubler et al. 1978). The outbreaks in Tahiti, New Caledonia, and Niue were all explosive and spread rapidly, infecting from 40 – 50% on New Caledonia and Tahiti and up to 90% on Niue. These outbreaks were of severe classical dengue fever and associated with high virus isolation rates (> 75%) (Gubler, 1997). Hemorrhagic disease was observed as more common and severe particularly in Tahiti (Moreau et al. 1973) and Niue, where there were 12 deaths, and the illness was recorded as being of a more distinctly hemorrhagic form as opposed to manifesting as dengue shock syndrome caused by vascular leakage (Barnes and Rosen 1974, Rosen 1977, South Pacific Dengue Commission 1974). Other islands, such as American Samoa for which little epidemiological data is available, also experienced outbreaks during this time although of a character described subsequently as “smoldering” (Gubler 1997).

From 1971 through most of 1973, the Kingdom of Tonga remained unaffected by these epidemics on neighboring islands but given the progression of the epidemics, public health officials in Tonga anticipated an epidemic of corresponding severity on their island. In addition, high rainfall over the fall and winter of 1973 had led to greater than usual populations of Ae. aegypti as well as Ae. tabu, thus heightening concern (Gubler et al. 1978). Surprisingly, no major outbreak occurred. In January, 1974, one of us (DJG) requested that paired serum samples be collected from persons with viral syndrome in Tonga. Of eight patients tested, four were positive for dengue. Subsequently, serologic testing of serum samples collected in August 1973 for a filariasis survey, however, documented that DENV-2 had been introduced to Tonga sometime prior to August 1973 (Gubler, et al 1978). Again anticipating a large epidemic, investigation was initiated to study the magnitude and duration of viremia and the competence of the mosquito vector. However, only cases of mild illness, mostly viral syndrome, were observed. The number of people seeking medical attention at the hospital peaked at 165 in March and 127 in April of 1974 (South Pacific Dengue Commission 1974). Case numbers fell sharply thereafter, with dengue ceasing to be recognized by the end of October of the same year. Among those individuals who were either hospitalized or seen as outpatients, almost all had remarkably mild clinical manifestations of short duration. Incidence of hemorrhage was extremely low, rates of virus isolation were very low (~ 33%) and viremia in most patients was too low to infect mosquitoes (only one of six patients on whom mosquitoes were fed) (Gubler et al 1978).

Nonetheless, it was clear that mosquito and human populations on Tonga were capable of sustaining a severe DENV outbreak: in contrast to this 1974 DENV-2 outbreak in Tonga, a subsequent outbreak on the same islands in 1975 but this time involving DENV-1 was particularly severe. The latter virus' progression through the population of Tonga was explosive, the incidence of hemorrhage higher, and there was a fatality rate of 12 persons (compared to none previously) (Gubler, et al 1978). Among the few (11) serum samples collected from this outbreak, DENV-1 was isolated from 4 out of 6 patients with primary infections, including one 26-year-old female fatality with DHF. DENV-1 was also isolated in 1 out of the 4 patients with secondary infections. Thus, primary and secondary infections were roughly equal (Gubler et al. 1978).

In summary, all islands affected by dengue outbreaks from 1971 to 1974 and for which serological testing and/or isolates were collected had outbreaks of the American genotype of DENV-2. With the exception of American Samoa, islands from which DENV-2 was isolated previous to Tonga experienced sudden outbreaks that showed a rapid increase in the number of people affected and which were characterized by hemorrhagic disease of unusual severity and high viremia levels. In Tonga, however, the 1974 outbreak of the same serotype and genotype was remarkably mild, with the virus seemingly attenuated, and exhibiting near-silent transmission.

RESULTS

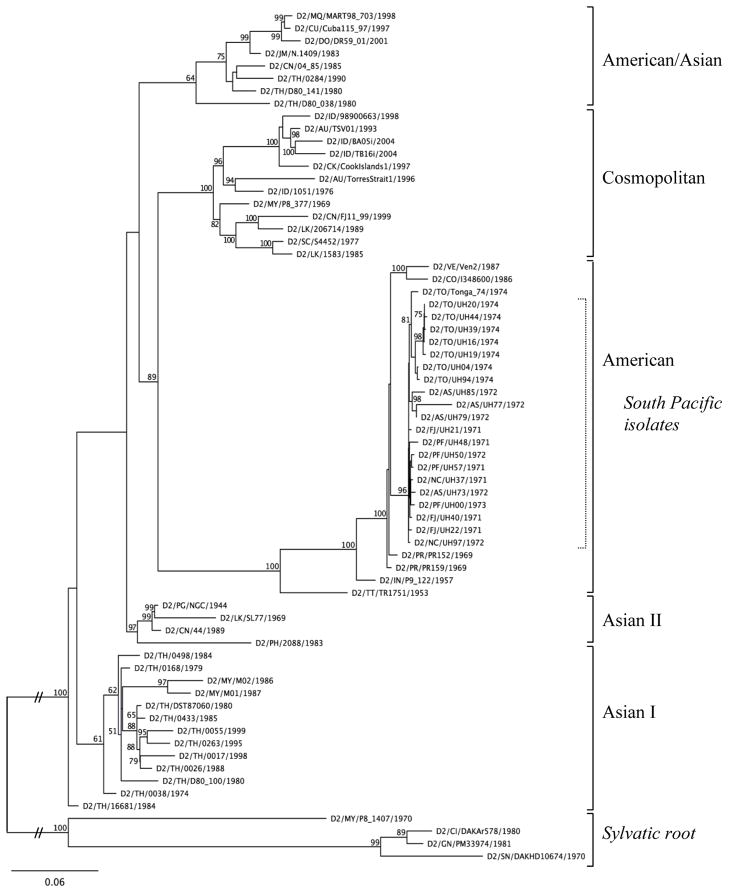

Sequence analysis. The maximum likelihood (ML) generated phylogenetic tree consisting of the 20 South Pacific isolates plus the additional 54 publicly available DENV-2 sequences (Fig. 1) unequivocally confirmed a) that the viruses isolated during the South Pacific epidemic sweep were of the same evolutionary lineage b) that these same isolates all belonged to the DENV-2 American genotype, which includes new world isolates dating back to the 1950s, and c) that all stemmed from a single introduction into the region from the Americas. PAUP*, MrBayes, and RAxML generated trees resulted in the same consensus topology.

Fig. 1.

ML tree of isolates from South Pacific sweep placed within other representative DENV-2 genotypes, including whole genome (Zhang et al. 2006) and E gene sequences (Twiddy et al. Virol 2002). E gene sequences from sylvatic DENV-2 strains used as outgroups to root tree. Node numbers are bootstrap support values from 100 ML replicates run in the RAxML program. A full list of accession numbers of the sequences used is available upon request.

Posterior node probabilities and bootstrap support values indicated 100% support for critical nodes on the tree, confirming both the robustness of the tree and the placement of the South Pacific isolates in a single clade within the American DENV-2 genotype.

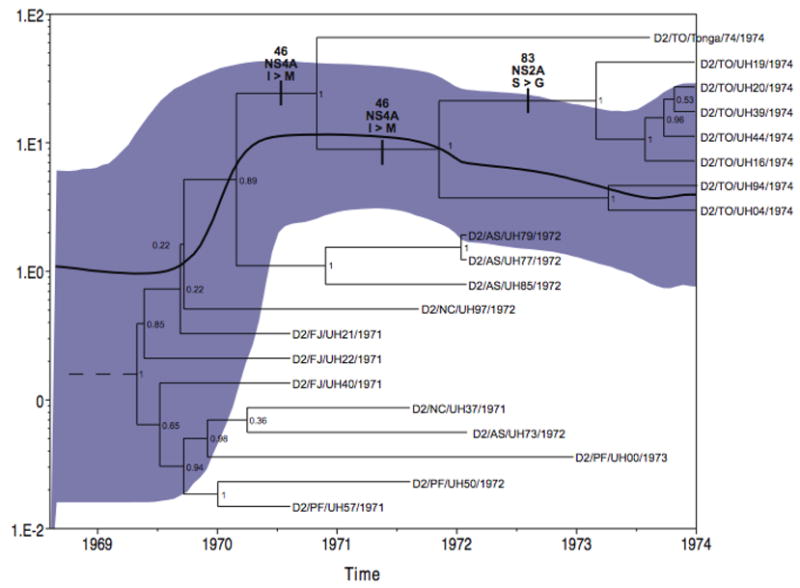

The maximum likelihood (ML) generated phylogenetic tree exclusively of the 20 South Pacific isolates rooted with other American genotype sequences (Fig. 2) revealed the Tonga sequences clustering into a distinctly monophyletic clade (posterior node probability of 1; strong bootstrap value of 97%, Supplementary Fig. 1A), lending support to the hypothesis that there is a genetic correlation to the observed clinical and epidemiologic attenuation. The Tonga clade also associated with the divergent and artificially evolved vaccine strain derived from Tonga (recombinant vaccine strain reported in Blaney et al. 2004, passaged 3 times after assembly and point mutations). Interestingly, 3 out of the 4 isolates from American Samoa, characterized by a “smoldering” and somewhat less intense epidemic during this period, group together but were distinct from the Tongan lineage (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Maximum clade credibility tree of isolates from South Pacific sweep on a temporal scale, aligned with the effective virus population size estimates (Bayesian Skyline plot) based on genetic diversity, both generated in BEAST (Drummond and Rambaut 2007). Tree labels indicate serotype/ISO 2-letter country-code/strain ID/year of collection. E gene sequences from American genotype strain of serotype 2, D2/PR/PR152/1969 (GenBank accession number AF264054) used as outgroup to root the tree. Node numbers are posterior node probabilities. Bold values are inferred amino acid substitutions that may correlate with strain attenuation. Corresponding Bayesian skyline plot shows mean effective number of infections (Ne) over the same time scale (solid black line, left-hand axis) with shaded area representing 95% high probability densities.

Amino acid substitutions associated with the Tonga clade. Mapping of the distribution of amino acid changes onto the Tonga clade allowed us to identify 3 distinct substitutions specifically associated with the Tongan samples; in NS4A which saw a change from an isoleucine to a methionine at gene amino acid residue 46 (I464AM) that defines all Tongan isolates including the artificially derived vaccine strain, in the pre-membrane (prM) gene region which had a histidine to arginine substitution at residue 54 (H54pMR) and defines all naturally isolated Tongan samples, and in NS2A which experienced a serine to glycine substitution at residue 83 (S832AG) and defines a subset of Tongan isolates (Fig. 2).

Analysis of rates of nonsynonymous (dN) to synonymous (dS) substitution identified no significant positive selection pressure on amino acid substitutions throughout the South Pacific outbreaks or specifically on the Tongan clade. Tests for recombination tentatively identified an incongruous Tahiti isolate which was removed from the list of compared sequences to await further analysis.

Viral demographics. Coalescent-based reconstruction of the demographic history of the American genotype DENV-2 in the South Pacific based on estimates of relative genetic diversity (Net) over time suggests that viral effective population sizes (Ne) experienced a decline representing a genetic bottleneck when introduced from the Caribbean. This was followed by an increase in diversity suggestive of exponential growth during first establishment in the South Pacific in 1971, followed by a brief decline starting around 1972 that did not reach former population lows and then what appears to be a period of slow or neutral growth beginning late 1973 (Fig. 2). This is consistent with epidemiologic data of large initial case numbers in 1971 followed by a waning: approximately 40,000 cases in Tahiti in 1971 (in the absence of consistent reporting, “it was estimated that at least half the population [of 80,000] was affected”, Moreau et al. 1973); 3,400 acute cases and at least 20,000 subclinical cases in Fiji in 1971 (Maguire et al. 1974); approximately 25,000 cases in the capitol of New Caledonia, 1971–1972 (extrapolated by the authors from a 40% affected rate of a population of 60,000, Loison et al. 1973); 790 diagnosed cases, but probably closer to 2070 symptomatic infections (45% affected rate of 4,600 people) in Nuie Island in 1972 (Barnes and Rosen 1974); 30 cases in American Samoa in 1972 (Gubler, D., Kuberski, T., and Rosen, L., unpublished data); and 24 confirmed cases, and fewer than 100 people reporting symptomatic illness in Tonga in 1974, population 95,000 (Gubler et al. 1978).

DISCUSSION

In this paper we address the relative importance of DENV strain variation to epidemic potential or virulence by focusing on a simplified transmission arena. Support for the differential virulence of strains began with experimental infections of human volunteers (Sabin 1952) and the use of attenuated strains as a basis for vaccine research (Blaney et al. 2004). This has been observed as well in numerous epidemiological studies reporting attenuation in Tonga (Gubler et al. 1978) and Indonesia (Gubler et al. 1981) as well as increased virulence and/or epidemic severity in Sri Lanka (Messer et al. 2002), Venezuela (Uzcategui et al. 2003), Peru (Watts et al. 1999) and the Western Hemisphere, with the displacement of the American genotype of DENV-2 by the more virulent Southeast Asian genotype (Rico-Hesse 1990, Cologna et al. 2005).

The evidence acquired from previous epidemiological studies suggests that discovering associations between genetic and epidemiological change may provide us with the best opportunity for inferring factors of epidemic potential and/or virulence. The South Pacific outbreaks analyzed here provide unique advantages allowing us to differentiate the effects of viral genetic variation from seropositivity rates and other factors:

All islands were relatively isolated and, except for Tahiti, had not seen DENV for 25–30 years.

The primary vector Ae. aegypti was equally abundant on all islands.

Host genetic makeup was relatively similar as island populations were either primarily Polynesian (Tahiti, Niue, American Samoa, Tonga) or Melanesian (New Caledonia, Fiji).

Well-documented epidemiologic, serological and clinical data are available for all isolates used in this study.

The transmission rate can affect epidemic severity and thus the role of mosquitoes in the differential DENV-2 transmission between islands bears examination. No information is available from the 1971 outbreak on Tahiti, but on Fiji Ae. aegypti was found in all areas of confirmed infection with the exception of the neighboring island of Rotuma. There, only the endemic species Ae. rotumae was detected (Maguire et al. 1974, South Pacific Comm. 1974). In New Caledonia Ae. aegypti mosquitoes were found to be abundant in all areas where dengue was occurring (Loison et al. 1973) while in Niue, although Ae. aegypti had not been reported previously, it was found subsequently and was assumed to be present during the outbreak (Barnes and Rosen 1974, South Pacific Comm. 1974).

A number of Aedes species, including Ae. aegypti, and Ae. tabu, were known to be present on Tonga during both the 1974 and 1975 outbreaks although overall numbers were lower in 1975 and while each species' relative numbers varied between Tongan island groups, these differences did not correspond to epidemic intensity (Gubler et al. 1978). Attempts to infect both Ae. aegypti and Ae. tabu by feeding on dengue patients were successful in only one case and subsequent examination of salivary glands found no DENV-2. Interestingly, infectivity evaluations using the Tonga strain as a basis for vaccine development (Blaney et al. 2004) also found that the strain failed to infect the midgut or head of Ae. aegypti, in contrast to the highly infectious DENV-2 New Guinea prototype strain.

Thus, there is no evidence that vector variation was responsible for the differences in epidemic behavior seen on the different islands involved in the 1971– 1974 DENV-2 outbreaks. The primary vector, Ae. aegypti, was found virtually on all islands in which dengue outbreaks occurred and is the most anthropophilic. While vector competency has been shown to vary between species as well as between different geographic populations of the same species (Rodhain and Rosen 1997), no correlation has been established between variations in competency on different South Pacific islands and their respective dengue epidemiology.

Evidence for some contribution of host factors to the epidemiological pattern seen in the South Pacific sweep is equally uncompelling. There were numerous cases of patients with pre-existing conditions that might have increased their susceptibility to hemorrhagic symptoms, yet no overall pattern between islands that would explain the attenuation of symptoms as seen in Tonga can be found. Likewise, while there is some evidence for inter-ethnic differences in dengue disease prevalence or severity, e.g., individuals of African descent appear to be less susceptible to DENV infection (Sierra et al. 2007a, Sierra et al. 2007b), host genetics in terms of ethnicity of the South Pacific islands involved do not appear to correspond with the pattern of DENV-2 outbreaks described. As noted above, the affected island populations were either primarily Polynesian (Tahiti, Niue, American Samoa, Tonga) or Melanesian (New Caledonia, Fiji). The most affected island, in terms of severity of symptoms and proportion of people infected, Niue, and the least affected, Tonga, are both made up primarily of Polynesians. Similarly, ethnicity did not influence the dramatically different epidemic outcomes on Tonga itself between the attenuated DENV-2 outbreak of 1974 and the 1975 DENV-1 outbreak with high associated morbidity.

There is no evidence therefore that variation in vector populations or host immunity were significant contributing factors to the differences in epidemic severity seen between islands (Gubler, et al, 1978). Rather, our results strongly suggest a viral basis for such differences. Observers of the original South Pacific dengue outbreaks assumed that the outbreaks on each island were caused by strains that were genetically and evolutionarily related to each other. Given the geographic isolation of these islands from the rest of the world, even greater then than today, such a belief was warranted. Nevertheless, there was always the possibility that the dramatic differences in epidemic behavior seen between Tonga and the other islands was simply due to the introduction of a different DENV-2 strain into Tonga. Phylogenetic analysis across all DENV-2 genotypes (Fig. 1) clearly shows that the viruses responsible for the South Pacific outbreaks were all genetically related and the result of a single introduction. The ML tree of isolates from the South Pacific, rooted with an American genotype outgroup (Fig. 2), provide further evidence that the Tonga DENV-2 strains are conclusively derived from the earlier Tahiti strains and not the result of a new introduction to the region, as shown by the formation of the monophyletic Tongan clade and the well-supported clustering of the Tonga clade with Tahiti, Fiji, and New Caledonia as closest relatives. The inclusion of the Tongan-derived, recombinant vaccine strain (Blaney et al. 2004) with the Tongan clade also demonstrates a shared genetic signature correlated with dramatic attenuation. Thus the DENV-2 phenotype of diminished disease incidence appears to be characteristic of all members of the clade and our phylogenetic analysis implicates specific synapomorphies (shared derived genetic substitutions) as the cause.

The causal molecular basis for how the above synapomorphies affect DENV attenuation is still unclear, however. If we consider the Tonga clade as including the vaccine strain, the primary amino acid synapomorphy associated with attenuation was I464AM, a nonconservative amino acid substitution resulting in the presence of a sulfur group with potentially large phenotypic effects. If we exclude the vaccine strain, as it had presumably been artificially selected, then the synapomorphies defining the Tongan clade expand to also include H54prMR, a somewhat more conservative substitution for a larger, more positive amino acid that may nonetheless have phenotypic repercussions. A subset of Tongan isolates was further distinguished by S832AG, also a nonconservative substitution, involving the loss of a potential phosphorylation/glycosylation residue for a metal-binding residue. Although potentially of large phenotypic effect, this last substitution was not shared by all Tongan isolates and therefore probably not the attenuating change.

Although our selection analysis suggest that none of these amino acid substitutions had accelerated fixation relative to silent substitutions, as one would see under strong positive selection, nonetheless these tests lack power under the small sample sizes (in terms of substitution) observed here and do not discount that the substitutions are phenotypically significant. While a number of studies have attempted to identify specific structural differences that correlate with clinical and/or epidemic outcome (Chen et al. 2008, Cologna and Rico-Hesse 2003, Cologna et al. 2005, Leitmeyer et al. 1999) there is insufficient evidence to identify consistent specific genetic factors associated with these DENV phenotypes. In our case, correlation of specific amino acid substitutions with epidemic attenuation implicates DENV genes (NS2A, NS4A and the prM) whose function is poorly understood.

NS2A and NS4A have both been implicated in the inhibition of the interferon-mediated antiviral immune response (Muñoz-Jordan et al. 2003) albeit to a lesser extent than NS4B. Interestingly, Umareddy et al. (2008) found that such inhibitory effects were strongly strain dependent (though not serotype-specific), again suggesting a molecular basis for strain variations in epidemic potential. NS2A genes may also play a role, along with NS4B, in anchoring the viral replicase complex to cellular lipid membranes (Chambers et al. 1989). NS2A has also been found to be evolutionarily significant, with adaptive substitutions affecting epidemic patterns, in Puerto Rico amongst DENV-4 strains (Bennett et al. 2003).

prM, a precursor to the M protein, is thought to promote infectivity of mature virions upon rearrangement of virion surface structure after proteolytic cleavage (Chang 1997). Leitmeyer et al. (1999) identified two amino acids in the prM that distinguished the more virulent Southeast Asian genotype of DENV-2 from the American and noted previous experiments (Bray and Lai 1991) that demonstrated the induction of protective antibody in mouse models upon exposure to the prM protein in combination with the membrane (M) protein.

Clearly, more work is required to determine whether the observed attenuation is due to the amino acid substitutions identified or other nucleotide substitutions that are either synonymous or occurred in the 5’ and 3’ non-translated regions. Regardless, the genetic substitutions defining the Tongan clade are consistent with a reduction in viremia and/or viral resistance to host interferon.

Our analysis of viral demographics during this period of epidemic expansion to near-silent transmission using the coalescent-based skyline plot (Fig. 2) offers an interesting perspective on such alternatives. Following a decline in diversity and virus effective population sizes after 1972, there appears to be a period of stasis in viral population sizes (in terms of numbers of infections) or possibly slow growth as DENV-2 arrived in Tonga. While this appears to contradict contemporary observations that the Tonga attenuation was notable for both fewer clinical infections and lowered case viremia, the 40% rate of secondary infection in the 1975 DENV-1 Tonga epidemic supports that DENV-2 infections in 1974 were more numerous than reports based on clinical data. Recall also that DENV-2 was first introduced into Tonga prior to August, 1973, based on antibody data, and that although symptomatic and confirmed cases were only noted beginning in 1974, silent transmission had already occurred by this time (Gubler et al 1978).

Dengue evolution has been characterized by vigorous purifying selection (Holmes 2003, Twiddy et al. J Gen Virol 2002), occasional positive selection on certain amino acid sites (Bennett et al. 2003, Bennett et al. 2006, Twiddy Virology 2002) and considerable genetic drift (Jarman et al. 2008), particularly important in small populations. Genetic drift might be expected to predominate as a force of evolutionary change in the South Pacific simply because islands experience relatively more population bottlenecks, that is, drastic reductions of individuals leading to random fixation. Along with the bottleneck at each blood meal, which captures only a subset of virus variants, some Pacific islands experience substantial seasonal variation in rainfall and/or temperature. Mosquito populations on such islands that are dependent upon seasonal rainfall can fluctuate dramatically during the year (Iyengar 1960). On the southerly Pacific islands, seasonal temperature changes can affect vector gonotrophic cycle and/or the extrinsic incubation period. Nor are these seasonal bottlenecks alleviated by vector immigration from off-island since the islands are relatively isolated. In addition, susceptible host populations experience rapid fluctuations on islands where human populations are limited, clustered so as to be more vulnerable to high rates of transmission, and less often infused with new susceptibles due to isolation by geographic distance. Finally, viral lineage diversity should decrease in proportion to smaller population sizes and the degree of diminished frequency of importation imposed by the geographic isolation inherent in islands. By all accounts, this isolation was even more pronounced at the time of the outbreak when between-island transportation was much more limited than today.

This examination of the evolutionary drivers of epidemic intensity takes advantage of the uniqueness of the South Pacific islands in the early 1970s. In contrast to those endemic/hyperendemic regions where the majority of dengue studies have taken place, such as Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, or South America, dengue viruses are not hyperendemic and serotypes rarely appear to co-circulate among island populations for any length of time. It may also be worth considering that the variety of vector species unique to the South Pacific may contribute to a high level of endemism, and furthermore that the mosquito species interacting with humans in the relatively non-urbanized communities of the South Pacific are potentially greater than in hyperendemic areas of dengue transmission, which are often dominated by Ae. aegypti. Numerous species of the subgenus Stegomyia, scutellaris group, are indigenous to various islands in the South Pacific (e.g., Ae. polynesiensis, Ae. hebrideus, Ae. cooki, Ae. rotumae, Ae. kesseli, Ae. tongae tabu, and Ae. tongae tongae) and include unique adaptations such as desiccation-resistant eggs (Huang and Hitchcock 1980, Rodhain and Rosen 1997). Given these factors, as well as the paucity of current research on dengue in the South Pacific, and the increasing impact of the disease on island populations, greater research in this region is warranted and provides opportunities to dissect DENV evolutionary dynamics in a non-hyperendemic arena.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses. The 20 isolates sequenced in this study were collected and annotated by Dr. Duane J. Gubler during the South Pacific outbreaks (See Table 1.) Note that none of the isolates came from patients exhibiting DHF as defined by WHO guidelines (WHO 1997).

Table 1.

Epidemiologic and clinical data for isolates used in this study.

| Strain ID | Pass† | Onset Date | Isolation: Date/Time | Disease§ | Age | Race | Sex | Travel History | Notes/Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D2/AS/UH73/1972 | 2* | 6/22/1972 | 1972 | febrile acute | 33 | P | M | American Samoa | |

| D2/AS/UH77/1972 | 2* | 6/21/1972 | 1972 | febrile acute | 50 | P | M | Never out of Am. Samoa | American Samoa |

| D2/AS/UH79/1972 | 2* | 6/21/1972 | 1972 | afebrile acute | 50 | P | M | Never out of Am. Samoa | American Samoa repeat of S5277 |

| D2/AS/UH85/1972 | 2* | 6/21/1972 | 1972 | febrile acute | 26 | P | F | Never out of Am. Samoa | American Samoa |

| D2/FJ/UH21/1971 | 4 | n.d. | 1971 | DF | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | Fiji |

| D2/FJ/UH40/1971 | 2 | n.d. | 1971 | DF | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | Fiji |

| D2/FJ/UH22/1971 | 3 | n.d. | 1971 | DF | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | Fiji |

| D2/NC/UH37/1971 | 2* | 12/31/1971 | 12/31/1971 | n.d. | 60 | C? | M | n.d. | New Caledonia |

| D2/NC/UH97/1972 | 2* | 1/26/1972 | 1/27/1972 8:15 A.M. | headache, joint pain | 49 | C | F | Born in France, in NC 1.5 yrs | New Caledonia |

| D2/PF/UH50/1972 | 3 | n.d. | 1972 | DF | 7 | n.d. | F | n.d. | French Polynesia |

| D2/PF/UH57/1971 | 2* | n.d. | 1971 | DF | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | French Polynesia |

| D2/PF/UH00/1973 | 2* | 4/12/1973 | 4/15/1973 | DF | n.d. | n.d. | F | n.d. | French Polynesia |

| D2/PF/UH48/1971 | 2* | n.d. | 1971 | DF | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | French Polynesia |

| D2/TO/UH16/1974 | 2* | 4/16/1974 | 4/16/1974 P.M. | febrile, myalgia, arthralgia, no rash nor hemorrhage | 16 | P | F | Never out of Tonga | Tonga |

| D2/TO/UH19/1974 | 2* | 4/16/1974 | 4/16/1974 7:30 P.M. | febrile | 16 | P | F | Never out of Tonga | Tonga, repeat of S14616 |

| D2/TO/UH20/1974 | 2* | 4/16/1974 | 4/17/1974 8:30 A.M. | febrile, myalgia, no rash nor hemorrhage | 19 | P | F | Never out of Tonga | Tonga |

| D2/TO/UH39/1974 | 2* | 4/17/1974 | 4/18/1974 2:30 P.M. | fever, headache | 16 | P | F | Never out of Tonga | Tonga |

| D2/TO/UH44/1974 | 2* | 4/16/1974 | 4/19/1974 11:30 A.M. | afebrile, headache no rash nor hemorrhage | 16 | P | F | Never out of Tonga | Tonga, repeat of S14616; 5th blood |

| D2/TO/UH94/1974 | 2* | 4/25/1974 | 4/26/1974 10:15 A.M. | febrile, hematemesis, melena, no other evidence of hemorrhage | 15 | P | F | Never out of Tonga | Tonga |

| D2/TO/UH04/1974 | 2* | 4/19/1974 | 4/26/1974 4 P.M. | febrile, head- ache, myalgia | 31 | P | M | Never out of Tonga | Tonga |

viral passage history

first passage in adult mosquito

All patients were classified as having classical dengue fever (DF). Additional clinical details are marked - DF indicates that no further clinical data is available. No patients exhibited dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) as defined by WHO criteria (WHO 1997).

Isolation of viral RNA, RT, PCR, and sequencing. Low passage isolates were used to infect C6/36 cells from which viral RNA was extracted using the QIAamp viral RNA mini kit (Qiagen). Reverse-transcription was performed using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen), and amplified by PCR using PfuUltra II Fusion HS DNA polymerase (Stratagene), using primers designed for 2X coverage of the entire ORF (RT-PCR conditions and primer sequences can be obtained from the corresponding author). Amplicons were separated by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels and puri ed using QIAquick Gel Extraction kits (Qiagen). Both strands of the resulting puri ed DNA fragments were sequenced at the UH Manoa Advanced Studies in Genomics, Proteomics and Bioinformatics sequencing facility using an Applied Biosystems 3730XL DNA Analyzer.

Sequence analysis. Sequencher 4.7 (Gene Code Corp.) was used to edit and align completed genomes and alignments verified in Se-Al 2.0 (Rambaut 2002). To provide genotypic, geographic and temporal context, 54 publicly available sequences spanning all known DENV-2 genotypes and representing a comprehensive and diverse assemblage of dengue viruses across the serotype were aligned with the South Pacific isolates as above. Alignments were imported into PAUP* 4.0b10 (Swofford 2003) and RAxML (Stamatakis 2008) for phylogenetic analysis. A full list of accession numbers of the sequences used is available upon request.

Evolutionary relationships among the South Pacific DENV-2 isolates were inferred using maximum likelihood (ML) to generate two phylogenetic trees. The first ML tree provided a genotypic context for the 20 South Pacific isolates and examines whether in situ evolution rather than multiple source introduction has occurred by including the 54 publicly available sequences (mentioned above), rooted with four sylvatic serotype-2 strains (Genbank accession numbers AF231719, AF231718, AF231717, AF231720). The second tree consisting only of South Pacific isolates rooted with an older American genotype from Puerto Rico, 1969 (Genbank accession number AF264054) as an outgroup examines whether Tonga isolates form a unique and distinct clade apart from the other South Pacific sequences.

Trees were estimated using the best fitting model of nucleotide substitution identified by Modeltest 3.7 (Posada and Crandall 1998); the Tamura-Nei plus Gamma plus I model that in- rate parameters (A-C = 1.0, A-G =13.913, A-T = 1.0, C-G = 1.0, C-T = 39.9977, G-T = 1.0), with a gamma distribution of among-site rate variation (4 categories) with a shape parameter (〈) of 0.9517 and 69.2% invariable sites (substitution model TrN+I+G). Phylogenies in PAUP* were generated under successive rounds of subtree pruning-regrafting (SPR) branch swapping, updating parameter estimates at each round.

ML tree topologies and node support were verified by generating Bayesian posterior probability values for each node using MrBayes (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001, Ronquist et al. 2003) based on 10,000,000 generations, ESS (effective sample size) of at least 100, and burnin of 12000. The average standard deviation of split frequencies between 4 MCMC chains was 0.012386 (South Pacific isolates plus 54 added DENV-2 sequences) and 0. 021130 (South Pacific isolates plus American outgroup). In addition, 100 ML bootstrap replicates were implemented in the RAxML BlackBox web server (Stamatakis 2008) as an additional measure of node support. A GTR plus G plus I model of evolution similar to that above was used in both cases, since MrBayes and RAxML BlackBox cannot accommodate the TrN93 model. Node support values and topologies generated from all three methods - PAUP*, MrBayes and RAxML BlackBox - were virtually identical, thus our phylogenies show results from the latter method only (RAxML tree, PAUP* ML and MrBayes consensus trees for the South Pacific ingroup are available as Supplementary Figures 1A, B, and C, respectively).

Tests for recombination among the South Pacific DENV-2 isolates were carried out using the GARD detection method with the TrN93 nucleotide substitution bias model (chosen by the Hy-Phy automatic model selection tool), Beta-Gamma rate variation and 3 rate classes (DataMonkey.org). In the event that breakpoints were found, alternative phylogenies were explored by generating neighbor joining trees with bootstrap resampling (100 replications) in PAUP* for the multiple alignments of South Pacific sequences on either side of the breakpoint and under the same model of evolution.

As a means of identifying whether the Tonga attenuated phenotype correlated with specific genetic changes, we used a parsimony approach implemented in MacClade 4.08 (Maddison and Maddison, 2003) to map the most parsimonious distribution of amino acid changes onto the branches of the ML phylogenetic tree made up of the 20 South Pacific isolates, noting amino acid changes that occurred on branches both antecedent and within the Tonga clade.

To determine whether substitutions amongst the South Pacific isolates had been fixed by positive selection rather than random genetic drift, we estimated the relative rates of nonsynonymous (dN) to synonymous (dS) nucleotide substitutions across coding portions of a multiple alignment that included the South Pacific isolates as well as the four American genotype out-group sequences. We utilized two methods to assess the extent of adaptive evolution among the taxa in this alignment; PARRIS (rates across the alignment) and GABranch (rates on individual branches) (DataMonkey.org). Both methods were run under the TrN93 nucleotide substitution bias model.

Epidemiologic observations suggest dramatic changes in virus population sizes throughout this period. Virus population sizes are expected to have been mounting during the 1971–72 series of epidemics, but may have dropped dramatically in Tonga in 1974. Effective population size for a virus like dengue is a function of the census population size (estimated from confirmed cases) divided by the variance in successful subsequent transmissions, or in other words, the effective number of infections, those that go on to produce subsequent infections. We estimated virus effective population sizes (Ne) over the timespan of our study as a function of relative virus genetic diversity amongst sequences isolated at different points in time. Most isolates in our study were dated to month and day of sampling. Relative genetic diversity (Net, where t is the generation time, set to 2 weeks for DENV) is an indicator of effective population size under a neutral evolutionary process based on coalescent theory. We used a Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) inference framework in the program BEAST to independently estimate relative genetic diversity and Ne while incorporating uncertainty in the phylogeny by integrating across tree topologies (Drummond and Rambaut 2007).

Within BEAST we used the Bayesian Skyline model, employing a relaxed uncorrelated log-normal molecular clock model and a codon model of substitution (Goldman and Yang 1994), chosen over a strict clock model on the basis of a likelihood ratio test and AIC. Chain length for MCMC sampling was 25 million generations, sampling every 1000 generations. Adequate convergence of the chain’s effective sample sizes was assessed in Tracer (1.4.1, Drummond and Rambaut 2007). Statistical uncertainty in mean Ne estimates is reflected in 95% Highest Probability Densities (HPD). MCC topologies were generated in the TreeAnnotator program and were identical to topologies generated by the other tree estimation methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Chase Akins, Brandi Mueller, Maya Devi Paidi, Sharyse Hagino, and William White for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH-RR018727, CO-BRE Bioinformatics Facility, NIH-AI065359, NIH-RR003061, DOD-06187000 and NSF-IGERT 0549514.

References

- Barnes W, Rosen L. Fatal hemorrhagic disease and shock associated with primary dengue infection on a Pacific island. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1974;23:495–506. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1974.23.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S, Holmes E, Chirivella M, Rodriguez D, Beltran M, Vorndam V, Gubler D, McMillan W. Selection-driven evolution of emergent dengue virus. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:1650–8. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S, Holmes E, Chirivella M, Rodriguez D, Beltran M, Vorndam V, Gubler D, McMillan W. Molecular evolution of dengue 2 virus in Puerto Rico: positive selection in the viral envelope accompanies clade reintroduction. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:885–93. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81309-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaney J, Hanson C, Hanley K, Murphy B, Whitehead S. Vaccine candidates derived from a novel infectious cDNA clone of an American genotype dengue virus type 2. BMC Infect Dis. 2004;4:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-4-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray M, Lai C. Dengue virus premembrane and membrane proteins elicit a protective immune response. Virology. 1991;185:505–8. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90809-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers T, McCourt D, Rice C. Yellow fever virus proteins NS2A, NS2B, and NS4B: identification and partial N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis. Virology. 1989;169:100–9. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang G. Molecular biology of dengue viruses. In: Gubler D, Kuno G, editors. Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. CAB International; New York: 1997. pp. 175–198. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Lin S, Liu H, King C, Hsieh S, Wang W. Evolution of dengue virus type 2 during two consecutive outbreaks with an increase in severity in southern Taiwan in 2001–2002. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:495–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cologna R, Armstrong P, Rico-Hesse R. Selection for virulent dengue viruses occurs in humans and mosquitoes. J Virol. 2005;79:853–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.853-859.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cologna R, Rico-Hesse R. American genotype structures decrease dengue virus output from human monocytes and dendritic cells. J Virol. 2003;77:3929–38. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.7.3929-3938.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A, Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman N, Yang Z. A codon-based model of nucleotide substitution for protein-coding DNA sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 1994;11:725–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler DJ. Dengue. In: Monath TP, editor. Epidemiology of arthropod-borne viral diseases. CRC Press, Inc; Boca Raton, Fla: 1988. pp. 223–260. [Google Scholar]

- Gubler D. Dengue an dengue hemorrhagic fever: its history and resurgence as a global public health problem. In: Gubler D, Kuno G, editors. Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. CAB International; New York: 1997. pp. 175–198. [Google Scholar]

- Gubler D. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:480–96. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler D, Reed D, Rosen L, Hitchcock J. Epidemiologic, clinical, and virologic observations on dengue in the Kingdom of Tonga. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27:581–9. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1978.27.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler D, Suharyono W, Lubis I, Eram S, Gunarso S. Epidemic dengue 3 in central Java, associated with low viremia in man. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30:1094–9. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1981.30.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead S. Pathogenesis of dengue: challenges to molecular biology. Science. 1988;239:476–81. doi: 10.1126/science.3277268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead S. Dengue. Lancet. 2007;370:1644–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61687-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E. Patterns of intra- and interhost nonsynonymous variation reveal strong purifying selection in dengue virus. J Virol. 2003;77:11296–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.20.11296-11298.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y-M, Hitchcock JD. Medical Entomology Studies – XII. A Revision of the Aedes Scutellaris Group of Tonga (Diptera: Culicidae) Contributions of the American Entomological Institute. 1980;17(3):111. [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck J, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bio-informatics. 2001;17:754–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarman R, Holmes E, Rodpradit P, Klungthong C, Gibbons R, Nisalak A, Rothman A, Libraty D, Ennis F, Mammen M, Endy T. Microevolution of Dengue viruses circulating among primary school children in Kamphaeng Phet, Thailand. J Virol. 2008;82:5494–500. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02728-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laigret J, Rosen L, Scholammer G. 1967[On an epidemic of dengue occurring in Tahiti in 1964. Relations to the "hemorrhagic fevers" of Southeast Asia] Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1967;60(14):339–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitmeyer K, Vaughn D, Watts D, Salas R, Villalobos I, de Chacon, Ramos C, Rico-Hesse R. Dengue virus structural differences that correlate with pathogenesis. J Virol. 1999;73:4738–47. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4738-4747.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loison G, Rosen L, Papillaud J, Tomasini J, Vaujany J, Chanalet G. La dengue en Nouvelle-Caledonie (1971–1972) Bulletin de la Societe de Pathologie Exotique. 1973;66:511–519. [Google Scholar]

- Maddison D, Maddison W. MacClade 4: Analysis of phylogeny and character evolution. Version 4.06. Sinauer Associates; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire T, Miles J, Macnamara F, Wilkinson P, Austin F, Mataika J. Mosquito-borne infections in Fiji. V. The 1971–73 dengue epidemic. Journal of Hygiene. 1974;73:263–70. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400024116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer W, Vitarana U, Sivananthan K, Elvtigala J, Preethimala L, Ramesh R, Withana N, Gubler D, de Silva A. Epidemiology of dengue in Sri Lanka before and after the emergence of epidemic dengue hemorrhagic fever. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:765–73. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau J, Rosen L, Saugrain J, Lagraulet J. An epidemic of dengue on Tahiti associated with hemorrhagic manifestations. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1973;22:237–41. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1973.22.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Jordan J, Sánchez-Burgos G, Laurent-Rolle M, García-Sastre A. Inhibition of interferon signaling by dengue virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14333–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335168100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Crandall K. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A. SE-AL Sequence Alignment Editor, v2.0a11. University of Oxford; Oxford, UK: 2002. [Accessed February 11, 2010]. Available at: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/seal/ [Google Scholar]

- Rico-Hesse R. Molecular evolution and distribution of dengue viruses type 1 and 2 in nature. Virology. 1990;174:479–93. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90102-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodhain F, Rosen L. Mosquito vectors and dengue virus-vector relationships. In: Gubler D, Kuno G, editors. Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. CAB International; New York: 1997. pp. 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck J. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–4. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen L. The Emperor's New Clothes revisited, or reflections on the pathogenesis of dengue hemorrhagic fever. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1977;26:337–43. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1977.26.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabin A. Research on dengue during World War II. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1952;1:30–50. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1952.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saugrain J, Rosen L, Outin-Fabre D, Moreau JP. A recent epidemic due to arbovirus infections of the dengue type in Tahiti. Comparative study of the 1964 epidemic. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1970;63:636–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra B, Alegre R, Pérez A, García G, Sturn-Ramirez K, Obasanjo O, Aguirre E, Alvarez M, Rodriguez-Roche R, Valdés L, Kanki P, Guzman M. HLA-A, -B, -C, and -DRB1 allele frequencies in Cuban individuals with antecedents of dengue 2 disease: advantages of the Cuban population for HLA studies of dengue virus infection. Hum Immunol. 2007;68:531–40. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra BL, Kourí G, Guzman M. Race: a risk factor for dengue hemorrhagic fever. Arch Virol. 2007;152:533–42. doi: 10.1007/s00705-006-0869-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South Pacific, Dengue Commission. Recent historical perspectives of dengue in the South Pacific. The South Pacific Commission Dengue Newsletter. 1974;1:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML Web servers. Systematic Biology. 2008;57:758–71. doi: 10.1080/10635150802429642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford D, Sullivan J. Phylogeny inference based on parsimony and other methods using PAUP*. In: Salemi M, Vandamme A-M, editors. The Phylogenetic Handbook: A Practical Approach to DNA and Protein Phylogeny. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2003. pp. 160–206. [Google Scholar]

- Tolou H, Couissinier-Paris P, Durand J, Mercier V, de Pina J, de Micco P, Billoir F, Charrel R, de Lamballerie X. Evidence for recombination in natural populations of dengue virus type 1 based on the analysis of complete genome sequences. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:1283–90. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-6-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twiddy S, Farrar J, Vinh Chau N, Wills B, Gould E, Gritsun T, Lloyd G, Holmes E. Phylogenetic relationships and differential selection pressures among genotypes of dengue-2 virus. Virology. 2002;298:63–72. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twiddy S, Holmes E. The extent of homologous recombination in members of the genus Flavivirus. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:429–40. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18660-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twiddy S, Woelk C, Holmes E. Phylogenetic evidence for adaptive evolution of dengue viruses in nature. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:1679–89. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-7-1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umareddy I, Tang K, Vasudevan S, Devi S, Hibberd M, Gu F. Dengue virus regulates type I interferon signalling in a strain-dependent manner in human cell lines. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:3052–62. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/001594-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzcategui N, Camacho D, Comach G, Cuello de Uzcategui R, Holmes E, Gould E. Molecular epidemiology of dengue type 2 virus in Venezuela: evidence for in situ virus evolution and recombination. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:2945–53. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-12-2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzcategui N, Comach G, Camacho D, Salcedo M, Cabello de Quintana M, Jimenez M, Sierra G, Cuello de Uzcategui R, James W, Turner S, Holmes E, Gould E. Molecular epidemiology of dengue virus type 3 in Venezuela. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:1569–75. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18807-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts D, Porter K, Putvatana P, Vasquez B, Calampa C, Hayes C, Halstead S. Failure of secondary infection with American genotype dengue 2 to cause dengue haemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 1999;354:1431–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever: Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention, and Control. Geneva: WHO; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/

- Worobey M, Rambaut A, Holmes E. Widespread intra-serotype recombination in natural populations of dengue virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7352–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Mammen M, Chinnawirotpisan P, Klungthong C, Rodpradit P, Nisalak A, Vaughn D, Nimmannitya S, Kalayanarooj S, Holmes E. Structure and age of genetic diversity of dengue virus type 2 in Thailand. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:873–83. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81486-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.