Abstract

This article reviews key facts about malaria to enhance prevention work and to promote the early diagnosis, treatment, and reporting of this complex disease.

Keywords: malaria, prevention and control, diagnosis, risk reduction, travel

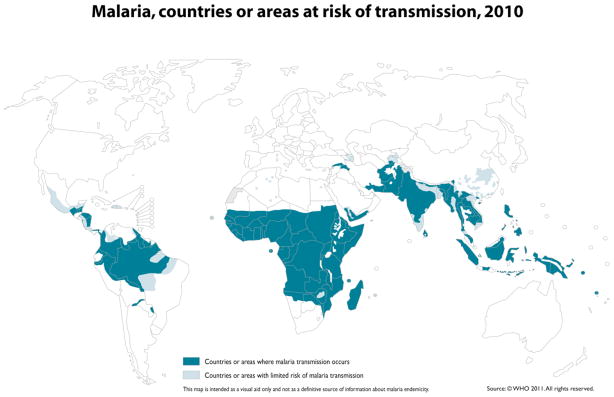

Mosquitoes are more than just a buzzing and biting annoyance—collectively, they are the most prolific killers of humans in the animal kingdom. The diseases that mosquitoes transmit have repeatedly changed the course of history, and malaria parasites are among the most ancient and deadly of these microorganisms.1,2 Across the millennia and up to the present, malaria has spread most easily in conditions of poverty, conflict, and displacement, which maximize exposure to biting mosquitoes and minimize access to treatment.3 Malaria parasites were transported to North America by 16th and 17th century European colonists, and transmission was perpetuated by the African slave trade, causing serious problems for troops during the Revolutionary and Civil Wars (Figure 1).4,5

Figure 1.

Areas of the U.S. believed to be malarious in 1882.

U.S. Army Medical Department. Communicable Diseases: Malaria. Coates JB (ed). Preventive Medicine in WWII. Volume 6. Washington: Surgeon General, United States Army, 1963.

A World War II initiative called “Malaria Control in War Areas” (1942–1945) was gradually transformed into the current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Through improved housing and socioeconomic conditions, as well as the availability of two new products—the synthetic drug chloroquine and the pesticide dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT)—the CDC goal to eradicate malaria in the United States was achieved by 1951.6 Over the next 50 years, however, the failure to eradicate malaria worldwide set the stage for a global resurgence and the continuous importation of these infectious organisms into malaria-free regions through travel, immigration, and commerce.4,7

Distribution and prevalence

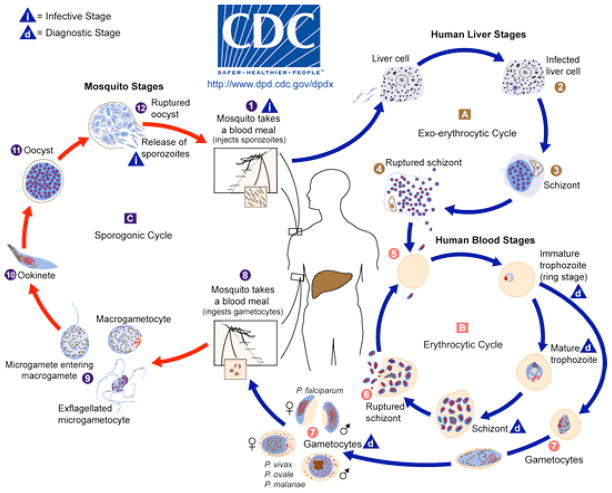

Malaria-risk regions form a belt around the tropical and subtropical latitudes of the earth (Figure 2), with the greatest disease burden in sub-Saharan Africa where it has been a major barrier to economic development.8,9 These malaria-endemic areas encompass many of the most densely populated regions on earth, where approximately 3.3 billion people (half of the world’s population) are at risk of bites from mosquitoes bearing malaria parasites.10 There are an estimated 350–500 million malaria cases and approximately one million deaths annually.11 Children in sub-Saharan Africa are infected 2 to 5 times/year on average and die from malaria complications at the rate of 1 to 2 children per minute.10

Figure 2.

Global distribution of malaria.

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of it authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

World Health Organization: Malaria, countries or areas at risk of transmission, 2010. http://gamapserver.who.int/mapLibrary/Files/Maps/Global_Malaria_ITHRiskMap.JPG

Malaria prevalence and distribution are impacted by environmental conditions that favor the reproduction of Anopheles mosquitoes and of the single-cell malaria parasites. These conditions include increased temperature and precipitation, deforestation, and a variety of housing, agricultural, and water projects that incidentally produce expanded mosquito habitat.12 As a consequence of the last global eradication effort in the 1940s-1950s, resistance developed to the insecticide DDT and the drug chloroquine. More recently, resistance to pyrethroid insecticides has been noted in Africa, and resistance to the newest antimalarial drug option has emerged near the Thai–Cambodian border, demonstrating that malaria control efforts continue to face serious challenges.13–15

The number of U.S. travelers who are diagnosed with malaria while abroad remains largely undocumented, while the proportion of travelers going to malaria-endemic destinations continues to rise among the 40.3 million U.S. outbound travelers per year.16 Malaria cases diagnosed in the United States have ranged between 1,278 and 1,564 case reports per year over the last 10 years for which data have been reported (2000–2009), with an average of 1,410 per year and a 14% increase in malaria cases from 2008–2009.17 Although most often spread by mosquitoes, this bloodborne disease can also be acquired through blood transfusion, needle sharing, organ transplant, or placental transfer from mother to fetus. In 2009, U.S. cases primarily involved malaria importation by travelers, soldiers, and foreign residents, with one transplant and two transfusion-related cases, three possible congenital cases, and 142 cases classified as severe malaria.17 There were 56 malaria deaths reported in the U.S. from 2000–2009 despite the availability of resources to prevent and to cure this disease among U.S. residents.17–21

The risk of death or disability rises when U.S. travelers become ill with malaria in regions of the world with unreliable access to healthcare products and services. Malaria is so prevalent in countries with intensive transmission that most cases never come to the attention of any formal health system.22 Individuals living in these regions are often infected repeatedly and may become chronically anemic as a consequence of limited access to diagnosis and treatment.23 Delayed testing or treatment with less effective regimens substantially increase the risk of serious illness, disability, or death, particularly in individuals with no prior immunity to these parasites. In non-endemic countries such as the United States, missed diagnoses are a concern due to a lack of familiarity with malaria manifestations in the traveler and immigrant populations.17

Between 1957 and 2003, there were 63 locally acquired mosquito-transmitted outbreaks in the United States in which 156 citizens with no history of travel or other risk factors were infected with malaria.4,24 Local spread occurs when individuals infected abroad are bitten by local mosquitoes capable of transmission, or when infected mosquitoes survive inadvertent air transport from remote locations and then seek a blood meal nearby (“airport malaria”).25 In either case, diagnosis may be delayed due to failure to suspect malaria in an individual who doesn’t fit the traveler, immigrant, military, or other bloodborne exposure profiles. Additionally, the impact of climate change on local ecosystems is shifting the geographic range of Anopheles mosquitoes,12 while the limited number of treatment and mosquito control compounds increases the likelihood of resistance emerging in parasites and mosquitoes.13,14 For these reasons, there is a continued threat of malaria transmission through local mosquito populations in places that are currently malaria-free.26 The number of U.S. malaria cases reported by state (Figure 3) shows the geographic dispersion of case reports.17

Figure 3.

Number of cases (N = 1,484) by state or territory in which malaria was diagnosed — United States, 2009.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria surveillance—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(3): 1–20.

Abbreviations: AS = American Samoa; GU = Guam; PR = Puerto Rico; VI = U.S. Virgin Islands.

Parasite/host interaction

Malaria is caused by one of four species of parasites in the genus Plasmodium–—P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, and P. malariae—with evidence that a fifth parasite associated with monkeys (wild macaques) in Southeast Asia can also infect humans.11 The first documented case of simian malaria with P. knowlesi in a U.S. traveler was reported in 2008.17 Only a subset of approximately 50 species of Anopheles mosquitoes have evolved to be capable of malaria transmission, but they are unfortunately widely dispersed globally. 26 These parasites are not just transported incidentally by the mosquitoes as they move from person to person to feed. Plasmodium parasites have evolved to require two complete cycles of development, one in humans and one in mosquitoes, in order to perpetuate the spread of this disease.

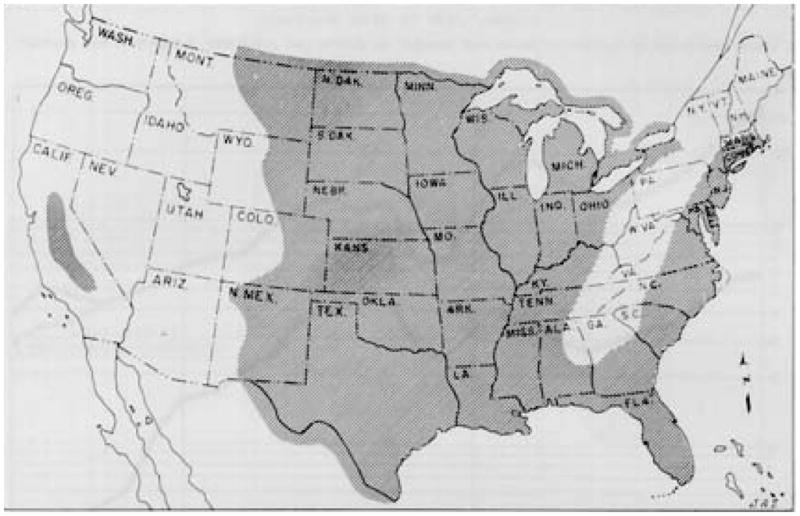

Malaria transmission begins with a female Anopheles mosquito seeking a blood meal to provide protein for egg development (Figure 4). If this mosquito feeds from a human carrying Plasmodium organisms at the right blood stage (male and female gametocytes), then the 10- to 21-day parasite lifecycle in the mosquito begins. Once sucked into the mosquito, these gametocytes unite to form a zygote. Zygotes penetrate the mosquito midgut where they reproduce and rupture to release sporozoites, which migrate to the mosquito salivary glands and are then injected into a human during another blood meal when saliva is pumped into the bite to prevent blood coagulation.

Figure 4.

Parasite/host interactions.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011): http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/biology/index.html

Once in the blood or lymph channels of a human being, the sporozoites enter liver cells within 30 to 60 minutes, where they evade host immune defenses while waiting to begin asexual reproduction. This waiting period can range from 7 days to a year or more depending on the species of parasite. P. falciparum tends to cause symptoms within the first 3 months after exposure. About 40,000 replications can be produced for every parasite that enters the body. This rapid reproduction causes the rupture and release of thousands of newly formed merozoite-stage parasites into the bloodstream, ending the “quiet” asymptomatic phase of infection.

The merozoites are motile oval-shaped organisms that invade red blood cells (RBCs) and rapidly consume hemoglobin while continuing to multiply to the point of large-scale RBC destruction. After a series of asexual reproductive cycles, a subpopulation develops into gametocytes from among the millions of Plasmodium parasites that are by now circulating in the person’s blood. These male and female gametocytes are available to infect the next blood-seeking mosquito, continuing this cycle of alternating sexual and asexual reproduction that is common among parasites.

Clinical presentation

Fever is the most universal indicator of malaria infection, but the clinical presentation may also include headache, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cough, joint pain, abdominal pain, and back pain. A classic malaria attack involves a cyclic pattern of sudden onset of chills followed by high fever and sweating over 4 to 10 hours that, if untreated, repeats every 2 to 3 days depending on the parasite species. This pattern mirrors the cycles of RBC invasion, reproduction, and rupture by parasites. Ongoing RBC destruction leads to obstructed blood vessels, anemia, jaundice, and an enlarged liver or spleen. The clinical course of malaria is less predictable in individuals with no prior exposure, such as travelers. Exposure to repeated infection may result in chronic anemia, jaundice, and fatigue.

Malaria caused by P. falciparum is especially dangerous because affected cells are most likely to stick to the walls of capillaries and block the flow of blood. This acute vascular occlusion can precipitate neurologic, respiratory, renal, and circulatory collapse. A delayed onset of symptoms and relapse is most common with P. vivax and P. ovale. Fatalities are possible with all types of malaria, although P. falciparum is most lethal on a global scale.13 Cerebral malaria is a medical emergency that presents with altered mental status, confusion, and disorientation. These changes may precede a rapid decline to coma and death, so considering malaria in a differential diagnosis for sudden-onset cognitive changes can be lifesaving.

It takes at least 7 days to move from parasite transmission to the onset of symptoms, so travelers should be informed that fever in the first week of travel is unlikely to be malaria, although any illness should be promptly evaluated.11 Conversely, travelers may be home before noticing any signs or symptoms of illness because it can take several months or more to move beyond the dormant liver stage. Pregnant women are generally advised to avoid travel to malarious areas due to a higher risk of developing severe illness. Children less than 5 years of age, and travelers from non-endemic areas, are also at higher risk due to limited or no prior exposure.

Diagnosis and treatment

Prompt diagnosis is critical because delays increase the risk for serious illness, disability, and death. A febrile individual who has visited or emigrated from a malaria-endemic region (Figure 2) in the past year should be considered to have malaria until proven otherwise. Fever and flulike symptoms most often occur within 3 months of the bite of an infected mosquito. The most important action is to ask all febrile patients about travel, emigration, and blood exposures. When there is a positive exposure history, or if the clinical picture suggests malaria despite a negative exposure history, thick and thin blood smears should be done to check for parasites, preferably while the patient is febrile. When the first thick and thin blood smears are negative, follow-up blood smears should be conducted every 8 to 12 hours for 2 to 3 days to monitor for blood-stage parasites. Other lab tests that may be helpful in making a diagnosis are a complete blood count to check for anemia or the presence of other infections, liver function tests, and a blood glucose test to check for hypoglycemia (parasitized RBCs utilize glucose 75 times faster than cells not infected with malaria parasites).

Giemsa-stained ‘thick’ smears are done to determine if parasites are present in the blood; if so, all species and stages of development will be counted. ‘Thin’ smears are used to identify the Plasmodium species and to estimate the percentage of RBCs infected. More than one species may be detected on the thin smear. Newer tests such as rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) and polymerase chain reaction tests (PCRs) can supplement but not yet replace microscopy. The first FDA approval of an RDT was in 2007 (BinaxNOW Malaria Test), with continuing efforts to improve RDT sensitivity, specificity, and ease of use. There are also new serologic tests to measure past exposure to malaria using indirect immunfluorescence (IFA) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Drug-resistance tests to assess susceptibility of identified parasites to antimalarial compounds are performed in specialized labs.

In order to determine the severity of illness and the appropriate treatment following diagnosis, consultation with a specialist in travel medicine or infectious disease is strongly advised. Malaria is a notifiable disease, so clinicians are mandated to report all lab-confirmed cases to the nearest health department, and to send a case report to the CDC (http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/report.html).17

Treatment depends upon the Plasmodium specie(s) detected, likelihood of drug resistance, severity of illness, and individual risk factors for complications.11 For uncomplicated disease, oral regimens include atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone), quinine, doxycycline, tetracycline, clindamycin, mefloquine, and chloroquine. Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) has been added to most national formularies with the endorsement of the World Health Organization (WHO) because ACT kills parasites more rapidly than any other antimalarial treatment, as well as being active against gametocytes and thereby preventing transmission from human to mosquito. The fixed-dose combination drug, artemether 20 mg/lumefantrine 120 mg (Coartem), received U.S. FDA approval in April 2009. Treatment with primaquine may also be required for the dormant liver stage of P. vivax and P. ovale associated with relapsing disease. Individuals with severe malaria should be hospitalized to receive I.V. antimalarial medication; kidney dialysis, blood transfusions, and oxygen therapy may also be needed. See http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/diagnosis_treatment/treatment.html for treatment guidelines for both oral and I.V. therapy recommendations.

Because malaria is a bloodborne disease, U.S. residents cannot give blood for 3 years after living in an endemic area or being diagnosed and treated for malaria. Blood donations are not accepted for 1 year after travel to an endemic region for individuals without a diagnosis of malaria.

Special challenges

The range of clinical presentations and varying degree of severity make malaria surveillance and clinical management difficult. The number of organisms found in the blood does not directly correlate with the severity of illness. Individuals from areas of sustained transmission may have high parasite loads without showing any acute signs of illness,22 while fewer circulating parasites may cause serious illness for young children, pregnant women, and those without prior exposure.10 Immunity wanes without ongoing exposure, so individuals who have left an endemic area and then return to visit, such as U.S. immigrants, must take full precautions to avoid infection. Individuals who travel to malaria-endemic locations to “visit friends or relatives” (called VFR travelers) comprise a uniquely susceptible group because they are more likely to depart without a travel consultation, to misunderstand travel recommendations due to language or cultural barriers, and to fail to use an antimalarial medication or mosquito-bite-avoidance measures for reasons such as cost or a false sense of security.28 Thus, the VFR group is overrepresented among the cases of imported malaria, and these individuals deserve additional focus for prevention services and education about the need for early intervention if symptoms develop.

The calculation of a U.S. malaria case fatality rate is complex due to the difficulty of determining the number of U.S. residents who are exposed to malaria in a set period of time. However, data collected from personnel assigned to U.S. diplomatic posts abroad between 1988 and 2004 showed 3 deaths among 684 confirmed malaria cases (0.44% mortality).29 A review of malaria-related deaths among U.S. travelers from 1963 to 2001 found an estimated case-fatality rate of 0.9%, and 1.3% for P. falciparum specifically (1985–2001 data), revealing that 1 in every 100 travelers with P. falciparum diagnosed and reported after returning to the United States died.30 Further analysis indicated that almost all deaths were preventable and attributable to mistakes made by: 1) healthcare providers who failed to prescribe the correct antimalarial regimen, to diagnose malaria on initial presentation, and/or to start treatment promptly using the correct protocol; and 2) ill individuals who did not seek pretravel advice, used inadequate prevention measures, and/or delayed seeking care after symptom onset.

Prevention measures for travelers

The key to pretravel risk assessment is the specificity of the questions and the accuracy of the information about destination and individual risks. A trip-planning interview should include all anticipated destinations, travel dates including length of stay, and purpose of travel (e.g., tourism, business, VFR, missionary, student/teacher, military). Destination refers not only to the country, but also to the specific location within a country. Other factors to assess are planned activities, type of accommodations, and the individual’s health status. Many infectious diseases, including malaria, show seasonal variations. In tropical regions, seasons may be referred to as “rainy” or “dry” rather than “summer” or “winter.” Sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania are particularly dangerous due to a high risk for P. falciparum transmission. Transmission risk increases with longer stays, exposure to the rainy season or flooding, using housing without air conditioning or screens for windows and doors, and belonging to the VFR category of travelers who are less likely to consistently use prevention measures while abroad.11,28 Women who are pregnant or likely to become pregnant should be advised to avoid travel to malaria-endemic regions due to increased risk of severe malaria and adverse pregnancy outcomes. The WHO provides a helpful acronym for remembering the ABCD of malaria risk reduction: Awareness (of risk, incubation period, main symptoms), Bite Precautions (mosquito avoidance between dusk and dawn) Chemoprophylaxis (antimalarial drugs to suppress infection where appropriate), and Diagnosis (immediately seek diagnosis/treatment if fever develops one week or more after entering an area where there is malaria risk, and for months after return).

With no vaccine yet approved for general use, and no other prevention measure that guarantees complete protection from malaria, travelers should be advised to use a combination of protective strategies. Prevention efforts focus on mosquito-bite prevention and chemoprophylaxis with drugs that suppress the blood stage of malaria infections, thereby preventing malaria disease. Both the CDC and WHO provide static and interactive maps that display malaria-risk destinations, including information about chloroquine resistance and antimalarial medication options (Table 1). It is recommended that antimalarial medication be purchased before departure to avoid problems with quality control, contamination, counterfeit drugs, or being prescribed a drug that is inappropriate due to local resistance issues or an unsafe adverse reaction profile. Self-treatment medication may be appropriate for use with influenza-like illness when medical care will not be available within 24 hours of symptom onset.11 However, this treatment is a temporary measure and further assessment should be sought as soon as possible.

Table 1.

Chemoprophylaxis

| Anti-malarial medication | Dosing* (all taken with meals) | Precautions |

|---|---|---|

| Atovaquone 250 mg & Proguanil 100 mg(Malarone™) | Daily dose Start 1–2 days before departure Finish 7 days after return |

Contraindicated in persons with severe renal impairment Not recommended for infants or pregnant or breastfeeding women. |

| Doxycycline 100 mg | Daily dose Start 1–2 days before departure Finish 4 weeks after return |

Can cause esophageal irritation and photosensitivity. Do not use during pregnancy or with children <8 years old. |

| Mefloquine 228 mg base (250 mg salt) |

Weekly dose Start 1–2 weeks before departure Finish 4 weeks after return |

Contraindicated in persons with active depression, or a recent history of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, other major psychiatric disorders, or seizures. |

| Chloroquine phosphate 300 mg base (500 mg salt) |

Weekly dose Start 1–2 weeks before departure Finish 4 weeks after return |

Widespread resistance (use only for approved destinations). |

| Primaquine 30 mg base (52.6 mg salt) Prophylaxis for short term travel to P. vivax-predominant areas |

Daily dose Start 1–2 days before departure Finish 7 days after return |

Contraindicated in persons with G6PD deficiency, and during pregnancy and breastfeeding unless infant has normal G6PD level. |

| Primaquine 30 mg base (52.6 mg salt) Presumptive anti-relapse therapy for P. vivax and P. ovale following prolonged exposure |

Daily dose for 14 days after return | Contraindicated in persons with G6PD deficiency, and during pregnancy and breastfeeding unless infant has normal G6PD level. |

see CDC Guidelines for details, including pediatric dosing (an overdose can be fatal, so keep out of the reach of children)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Health Information for International Travel 2010. Atlanta, GA: Mosby;2009:138–139.

Travelers may not have control over environmental risk reduction measures such as removing standing water where mosquitoes breed or spraying interior walls, but they can choose to travel with an insecticide-impregnated bed net in case available housing fails to provide air-conditioning or screens on doors and windows. Travelers should pack clothing that provides maximum skin coverage during the dusk-to-dawn peak feeding period for Anopheles mosquitoes (light-colored long sleeves, long pants/skirts, shoes with socks, hat). To further increase protection, travelers can purchase clothing that is pretreated with permethrin insecticide by the manufacturer. Clothing may also be treated with permethrin spray or soak after purchase. Travelers should be advised to pack skin repellents such as N,N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide (DEET) and hydroxyethyl isobutyl piperidine carboxylate (picaridin). DEET (30% to 50%) has the greatest proven efficacy, while picaridin (7% to 20%) will require more frequent applications to exposed skin, particularly when sweating. Homeopathic remedies do not have proven efficacy for malaria prevention or treatment.

Prevention, Detection and Treatment Highlights

Inform travelers that a malaria vaccine is not yet commercially available and that malaria infection can be fatal if treatment is delayed. Therefore personal prevention measures are critical. An individualized travel health risk assessment will establish whether insect precautions are adequate, or whether anti-malarial medication is also indicated.

When evaluating fever, include questions about travel, military service abroad, and emigration from an endemic location.

-

For febrile individuals who have traveled to a malaria-endemic region, emergently conduct thick and thin blood smears to rule out malaria.

If negative, draw blood sequentially every 8–12 hours for 2–3 days because one negative blood smear does not rule out malaria.

When a malaria diagnosis is made, obtain consultation to determine severity and to plan treatment.

Travel health as a specialty

Although global travel has never been more accessible for so many people, the resurgence of old diseases–such as malaria and dengue–has increased the complexity of travel health decision-making. Many travelers continue to rely on a guidebook or travel agent for their travel advice, even when their destinations and activities entail greater risk.31–33 Malaria-endemic destinations may present travelers with numerous other threats to health and safety that should be considered, such as contaminated food and water, other vector-borne diseases, sexually transmitted infections, and unintentional injury such as motor vehicle accidents, fire, falls and drowning.34

A travel health specialist can provide detailed pretravel advice that includes risk assessment, education, vaccination, and prescription of medication tailored to an individual’s health history and travel plans. Popular tourist itineraries that may pose a risk include Amazon tours, African safaris and climbs of Kilimanjaro, and visits to temples in India and Cambodia.11 Students and faculty are increasingly collaborating on projects in Haiti, Papua New Guinea, sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East.35 Symptomatic individuals with a history of exposure to malaria transmission due to travel, emigration, or military service may be encountered in nearly any setting that employs NPs. This makes it necessary to have a working knowledge of diseases prevalent outside the United States, and to know where to access the most up-to-date and reliable information (Table 2).

Table 2.

Travel Health Resources

| American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene |

| Offers a certificate in clinical tropical medicine and travel health: www.astmh.org |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) |

| Website and publication Health Information for International Travel: wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel |

| Preventing Malaria in Travelers (brochure), fact sheets and posters: www.cdc.gov/malaria/references_resources/fsp.html |

| Test Your Knowledge About Malaria: www.cdc.gov/malaria/references_resources/interactive_training/ |

| International Society of Travel Medicine |

| Offers a certificate in Travel Health: www.istm.org |

| International Society for Infectious Diseases/Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases(ProMed) |

| Reports on emerging diseases worldwide: www.promedmail.org |

| U.S. Department of State |

| Information on visas and travel alerts: http://travel.state.gov/travel/travel_1744.html |

| World Health Organization (WHO) |

| Website and publication International Travel and Health: http://www.who.int/ith/en/ |

Summary

When malaria-infected individuals present in clinical settings, NPs can promote prompt diagnosis, consultation, and case reporting. When providing pretravel assessments and education, the recommended prevention measures are determined by the specifics of the individual and their destinations and activities. Emphasis should be placed on seeking immediate testing for potential malaria symptoms. If malaria chemoprophylaxis is warranted, also emphasize the importance of finishing the entire course of antimalarial medication after return. With clear directives and reliable sources for obtaining travel health information, travelers will be more likely to engage in protective behaviors before, during, and after their return from malaria-risk regions.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Elaine Rosenblatt, MSN, FNP-BC, CTH for her careful review of this article. This work was supported in part by an NIH/NINR fellowship [F31 NR010425-01A2]. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Coluzzi M. The clay feet of the malaria giant and its African roots: hypotheses and inferences about origin, spread and control of Plasmodium falciparum. Parassitologia. 1999;41(1–3):277–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartl DL. The origin of malaria: mixed messages from genetic diversity. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2(1):15–22. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heggenhougan H, Hackethal V, Vivek P. Report for the UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases. Geneva: 2003. The behavioral and social aspects of malaria and its control. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zucker JR. Changing patterns of autochthonous malaria transmission in the United States: a review of recent outbreaks. Emerg Infect Dis. 1996;2(1):37–43. doi: 10.3201/eid0201.960104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graves PM, Levine MM. Battling Malaria: Strengthening the US Military Malaria Vaccine Program. Washington: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The History of Malaria, an Ancient Disease. http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/history/index.htm.

- 7.Mendis K, Rietveld A, Warsame M, Bosman A, Greenwood B, Wernsdorfer WH. From malaria control to eradication: The WHO perspective. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14(7):802–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gollin D, Zimmermann C. Malaria: disease impacts and long-run income differences. 2007. Report of the Institute for the Study of Labor No. 2997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sachs J. Achieving the Millennium Development Goals—the case of malaria. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(2):115–117. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Malaria Fact Sheet, No 94. Geneva: 2009. pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Health Information for International Travel 2010. Atlanta: Mosby; 2009. pp. 128–159. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patz JA, Olson SH, Uejio CK, Gibbs H. Disease emergence from global climate and land use change. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(6):1473–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenwood BM, Fidock DA, Kyle DE, et al. Malaria: progress, perils, and prospects for eradication. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(4):1266–1276. doi: 10.1172/JCI33996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers WO, Sem R, Tero T, et al. Failure of artesunate-mefloquine combination therapy for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in southern Cambodia. Malar J. 2009;8:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Global Malaria Programme. Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. The technical basis for coordinated action against insecticide resistance: preserving the effectiveness of modern malaria vector control Meeting report; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 16.ITA Office of Travel and Tourism Industries. Outbound US citizen air traffic to overseas regions, Canada, and Mexico. http://tinet.ita.doc.gov/view/m-2010-O-001/index.html.

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria surveillance—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(3):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria surveillance—United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(SS-7):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria surveillance—United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(SS-2):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria Surveillance—United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(SS05):24–39. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria Surveillance–United States, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(SS05):9–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breman JG. The ears of the hippopotamus: manifestations, determinants, and estimates of the malaria burden. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64(1-2 suppl):1–11. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breman JG, Ailio MS, Mills A. Conquering the intolerable burden of malaria: what’s new, what’s needed: a summary. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71(2 suppl):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Locally acquired mosquito-transmitted malaria: a guide for investigations in the United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(RR13):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thang HD, Elsas RM, Veenstra J. Airport malaria: report of a case and a brief review of the literature. Neth J Med. 2002;60(11):441–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Enayati A, Hemingway J. Malaria management: past, present, and future. Annu Rev Entomol. 2010;55:569–591. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moonen B, Cohen JM, Snow RW, Slutsker L, Drakeley C, Smith DL, et al. Operational strategies to achieve and maintain malaria elimination. Lancet. 2010;376:1592–1603. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61269-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leder K, Tong S, Weld L, et al. Illness in travelers visiting friends and relatives: A review of the Geosentinel surveillance network. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(9):1185–1193. doi: 10.1086/507893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rathnam PJ, Bryan JP, Wolfe M. Epidemiology of malaria among United States Government personnel assigned to diplomatic posts. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76(2):260–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newman RD, Parise ME, Barber AM, Steketee RW. Malaria-related deaths among U.S. travelers, 1963–2001. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(7):547–555. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-7-200410050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartjes LB, Baumann LC, Henriques JB. Travel health risk perceptions and prevention behaviors of US study abroad students. J Travel Med. 2009;16(5):338–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamer DH, Connor BA. Travel health knowledge, attitudes, and practices among United States travelers. J Travel Med. 2004;11(1):23–26. doi: 10.2310/7060.2004.13577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LaRocque RC, Rao SR, Tsibris A, Lawton T, Barry MA, Marano N, Brunette G, Yanni E. Pre-travel health advice-seeking behavior among US international travelers departing from Boston Logan International Airport. J Travel Med. 2010;17(6):387–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00457.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tonellato DJ, Guse CE, Hargarten SW. Injury deaths of US citizens abroad: new data source, old travel problem. J Travel Med. 2009;16(5):304–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Institute of International Education. Top 25 Destinations of U.S. Study Abroad Students, 2007/08–2008/09. Open Doors Report on International Educational Exchange. 2010 November 10; Retrieved from http://www.iie.org/opendoors.