Abstract

Background

Travelers’ diarrhea (TD) is the most common medical complaint of international visitors to developing regions. Previous findings suggested that noroviruses (NoVs) are an underappreciated cause of TD.

Methods

In the present study we sought to define the presence of NoVs in 320 acute diarrheic stool samples collected from 299 U.S. students who travelled to Guadalajara, Cuernavaca or Puerto Vallarta, Mexico during 2007 and 2008. Conventional and quantitative real time PCR (qPCR) were employed to detect and determine NoV loads in stool samples. NoV strains were characterized by purification of viral RNA followed by sequencing of the viral capsid protein (VP1) gene. Sequences were compared using multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic trees were generated to evaluate the evolutionary relatedness of the viral strains associated with TD cases.

Results

NoV RNA was detected in 9.4% (30 of 320) of the samples. Twelve strains belonged to Genogroup I (GI) and 18 to GII. NoV prevalence was higher in the winter season compared to the summer season (23% vs. 7%, respectively, P=.001). cDNA viral loads of GI viruses were found to be ~500-fold higher than those of GII strains. Phylogenetic analysis revealed a diverse population of NoV strains over different locations and years.

Conclusions

NoV strains are important causes of TD in Mexico, especially during the wintertime, and U.S. students in Mexico may represent a suitable group for future NoV vaccine efficacy trials.

Introduction

Noroviruses (NoVs) are non-enveloped, single stranded, positive sense RNA viruses belonging to the family Caliciviridae, classified into five genogroups (GI to GV) based on sequence of the viral capsid protein VP1, of which GI, GII and GIV affect humans [1–3]. NoVs are recognized as one of the most common causes of non-bacterial gastroenteritis affecting people of all ages worldwide and are transmitted through contaminated food and water, person-to-person contact, or by mechanical transmission from environmental surfaces (i.e. through hand/mouth contact) [4–9].

Industrialized nations frequently report outbreaks occurring in restaurants, schools, cruise ships and healthcare settings [10–13] whereas in developing countries malnourished children or those without access to effective healthcare are at a higher risk of suffering significant morbidity and mortality[6].

Travelers’ diarrhea (TD) is the most common medical complaint of international visitors to tropical and semitropical regions [14–16] and although TD is most often caused by bacteria [17], travelers have been previously identified as a group at risk of contracting NoV-associated diarrhea [18–20]. NoVs have been shown to be the most commonly identified enteric pathogen after diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in studies carried out in travelers to Mexico [19, 20].

Our research team monitors groups of U.S. students traveling to Mexico as a model of TD, and previous findings suggested that NoVs were an underappreciated cause of TD marked by a continuous and diverse presence of viruses belonging to genogroups I (GI) and GII [18–20]. An explanation why travelers are highly affected by GI strains is still missing and little is known about naturally-occurring infection in locations where NoVs are endemic, including populations of international travelers to endemic areas.

The aims of this study were to determine the frequency of NoV-associated TD (NoV-TD) in U.S. students traveling to Mexico, characterize the strains responsible for causing disease, determine the cDNA viral load, and to characterize the clinical symptoms associated with NoV-TD.

Materials and Methods

Study design and case definitions

Adults of at least 18 years of age, experiencing TD acquired in Cuernavaca, Guadalajara or Puerto Vallarta during the years of 2007 and 2008 were evaluated for the presence of NoVs in diarrheal stools. TD was defined as the passage of ≥3 unformed stools within a 24-hour period associated with one or more of the following symptoms: abdominal pain or cramps, excessive gas/flatulence, nausea, vomiting, fever (≥100°F or ≥37.8°C), fecal urgency, blood and/or mucus in the stool, or tenesmus. Once TD was diagnosed, an illness stool was obtained, verified as being unformed by clinic staff and submitted to the microbiology laboratory for study. Exclusion criteria included previous enrollment, duration of diarrhea for more than 72 hours, clinically important underlying illness other than diarrhea, and in women, being pregnant or breast feeding for safety reasons because most of the students enrolled for epidemiologic studies also participate in clinical trials. In addition, patients were excluded if they had taken any antimicrobial against diarrheal pathogens within the pre-study week or anti-diarrheal agent within 12 hours of enrollment. All patients provided written informed consent. The study was approved by The University of Texas Health Science Center Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Stool specimens

All study participants were requested to submit stool samples within 48 hours of onset of diarrhea to the local travel clinics. Additional stool samples were collected from participants during any subsequent acute diarrheal episodes. Stool samples were processed as previously reported [17]. Aliquots of diarrheal stools were made, stored at −20°C and shipped on dry ice to our laboratory at the Center for Infectious Diseases in the University of Texas-School of Public Health, Houston, Texas for norovirus studies.

Collection of clinical information

Participants completed weekly diary cards designed to assess their daily health status during their stay in the country where the presence or absence of a number of gastrointestinal symptoms was recorded along with the number, time, and characteristics of all stools passed. Study subjects rated their signs and/or symptoms by severity scores according to the following scale: 0= no symptoms; 1= mild symptoms (tolerable, without interfering with normal activities; 2= moderate symptoms (distressing, forcing changes in normal activities); 3=severe symptoms (incapacitating, prohibiting performance of normal activities).

Detection and characterization of NoVs

A 10% (w/v) stool suspension was prepared with 0.01M PBS and clarified by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. Viral RNA was extracted from 200 µL of the 10% stool suspension with a QIAamp viral RNA kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the RNA was stored at −80°C until used.

Reverse transcription (RT) was carried out in 50 µL of a reaction mixture containing 75 pmoles of random hexamers (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham MA), 5 U of AMV-RT (Life Sciences inc. St. Petersburg, Fl), IX of AMV –RT Buffer (Life Sciences Inc. St. Petersburg, Fl), 10 mM of dNTP mix, 10 U of Protector RNase Inhibitor (Promega, Madison, WI), and 10 µL of RNA extract. The reaction was performed for 2 hours at 43°C and the enzyme was inactivated at 75°C for 5 minutes. The resulting cDNA was stored at −20°C until used in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays. A set of degenerate primers [21] was used for initial detection of NoVs. The PCR reaction mixture contained 5 µL of template cDNA, 5 U of AmpliTaq (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), IX of AmpliTaq Buffer I (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), 10 mM of dNTP mix, and 200nM of each primers. Genogrouping PCR assay was performed on positive samples using primers G1SKF, G1SKR, G2SKF and G2SKR [22]. All PCR products were separated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized under UV lamp after ethidium bromide staining.

Nucleotide sequence and phylogenetic analysis

PCR products resulting from the amplification with the GSK primer set were used to sequence the ORF1–ORF2 junction region of all GI-NoVs and GII-NoVs identified. PCR products were purified using a MinElute PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Viral DNA was sent to SeqWright (Houston, TX) for sequencing. Sequences were analyzed using BioEdit v.7.0.9.0 and aligned with Clustal W 2.0.10 (www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw) with default parameters. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining and Poisson correction methods [23, 24] with MEGA 4.0 (www.megasoftware.net) [25]. Significance of the taxonomic relationships was obtained by bootstrap analysis (1,000 replications) [26]. Assignment of genotypes used reference strains described by Zheng et al. [27].

The NoV sequences identified in the 2007–2008 Mexico cases were compared with those found in earlier studies in Mexico during 1998 and 2004 [19, 28] to determine relatedness of the viruses in one region over time.

Quantitative Real Time PCR

The quantitative real-time PCR was carried out in triplicate on an ABI StepOne Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using purified NoV GI or GII cDNA plasmids as standards and following the protocol described by Kageyama et al. [29]. Amplification data were analyzed with StepOne Real-Time PCR System Software Version 1.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were performed with the Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney U-test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Sample Collection

Stool samples from 320 discrete episodes of TD acquired during a short-term stay in Guadalajara, Cuernavaca or Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, during 2007 and 2008 were collected from 299 U.S. students. Of the 320 stool samples, 165 were collected from 152 individuals with TD in Guadalajara from June to August of 2007, 152 stool samples were collected from 147 individuals with TD acquired in Cuernavaca from December to February of 2007 as well as March–May and June–August of 2008 (Table 1) and 3 cases were collected from travelers to Puerto Vallarta. Overall, 17 travelers experienced recurrent diarrhea and the maximum number of samples corresponding to discrete episodes was two samples per subject. Travelers ranged in age from 19–45 years of age (mean: 24 years, median: 22 years) 72% of travelers were female and 96% were Caucasian.

Table 1.

NoV-Positive Diarrhea Stool Specimens Collected from Travelers with Diarrhea in Guadalajara or Cuernavaca, Mexico from 2007– 2008.

| 2007 | 2008 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guadalajara | |||

| Summer | 5/122 (4.1) | 1/43 (2.3) | 6/165 (3.6) |

| Cuernavaca | 16/127 (12.6) | 8/25 (32) | 24/152 (15.8) |

| Spring | 1/9 (11.1) | 0 | 1/9 (11.1) |

| Summer | 11/87 (12.6) | 1/8 (12.5) | 12/95 (12.6) |

| Winter | 4/31 (12.9) | 7/17 (41.1) | 11/48 (22.9) |

| Total | 21/249 (8.4) | 9/68 (13.2) | 30/317* (9.4) |

A total of 320 samples were collected, 3 samples from Puerto Vallarta which were all collected during the summer of 2007 and NoV negative are not listed. Total calculations were based on 320 samples.

Prevalence of NoV among TD Patients

In the present study, 9.4% (30/320) of the stool samples collected had detectable levels of NoV RNA and 9% (27/302) of travelers were infected by NoV. Most travelers had single bouts of NoV diarrhea and only 3 travelers experienced more than one episode of diarrhea where NoV was recovered (Table 1).

NoV infection was more prevalent among travelers to Cuernavaca than among those who traveled to Guadalajara (15.8% vs. 3.6%, P<.001). During the summer of 2007 in Guadalajara, 109 travelers experienced TD and provided 122 stool samples, of which 4% (5/122) were positive for NoV. In 2008 a similar prevalence was observed in the same location where only 2.3% (1/43) of the samples collected were positive for NoV. One hundred twenty seven stool samples were collected from 126 ill travelers to Cuernavaca during 2007 of which 12.6% (16/127) were positive for NoV. During 2008, 32% (8/25) of the stool samples were NoV-positive, resulting in the highest prevalence rate reported in this study. Overall, 15.8% (24/152) of the total samples collected from Cuernavaca were NoV-positive and the subset of samples collected from this location during the colder months (December to February, 2007 and 2008) presented the highest presence of NoV, where 22.9% (11/48) of stools were positive. None of the three stools collected from Puerto Vallarta were positive for NoV RNA.

NoV single infections (NoV-si) and NoV co-infections (NoV-co)

Information on the identification of bacterial pathogens was available for seventeen out of the 30 samples containing NoV. NoV-si was identified in 6 samples, and co-infections with bacteria (NoV-co) were present in the remaining 11 samples. ETEC was identified in 10 of NoV-co samples and one sample was positive for enteroaggregative E. coli. The overall prevalence of co-infections observed in the present study was 65% (13/20) with ETEC being the most prevalent co-pathogen identified, present in 92% of co-infections.

Clinical symptoms associated with NoV-TD

Clinical data was available from 23 of the 27 travelers who experienced NoV-TD. The majority of travelers recorded clinical symptoms representing a typical TD episode. Data from 3 travelers representing second independent episodes of diarrhea were excluded from the analysis since most travelers received treatment drugs after initial episodes since this population also takes part in pharmaceutical clinical trials. Among the recorded symptoms median scores suggest that abdominal cramping, flatulence and vomiting were experienced at a mild level while moderate levels of nausea and fecal urgency were recorded. None of the subjects reported experiencing fever during the illness. NoV-TD in the NoV-si (n=6) group was characterized by a mild level of flatulence and moderate to severe levels of nausea, abdominal cramping, vomiting, and fecal urgency while all symptoms were recorded to be at a mild level in the NoV-co group (n=11). We found that NoV single infection was associated with more severe vomiting compared with samples with more than one pathogen (p=0.047). Ninety percent of the stools collected from ill travelers with NoV-TD were watery with the rest being of soft consistency

Genetic Diversity of NoV Strains Identified

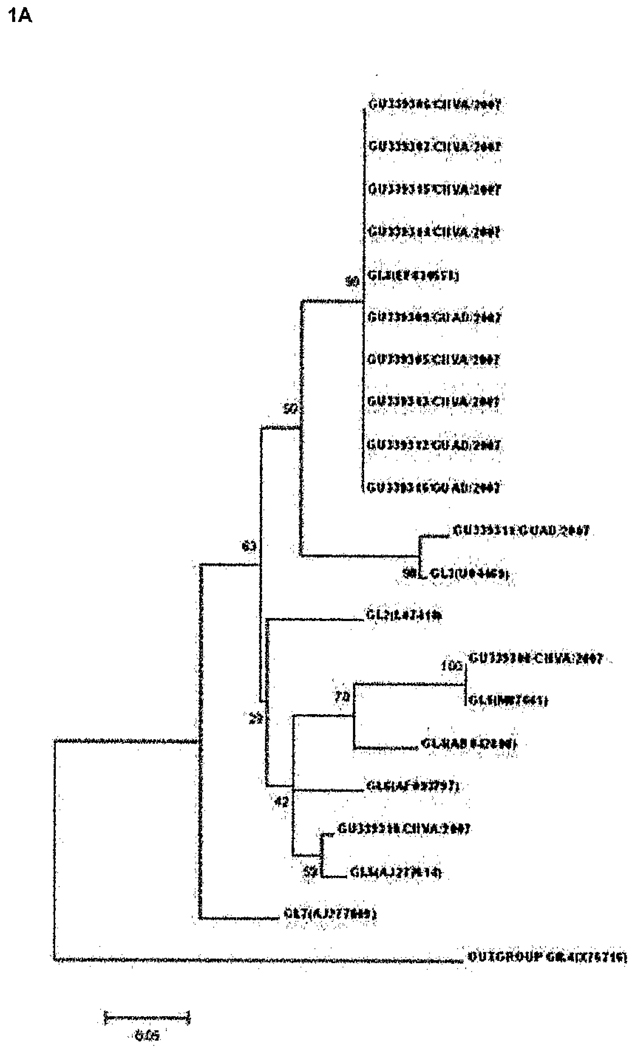

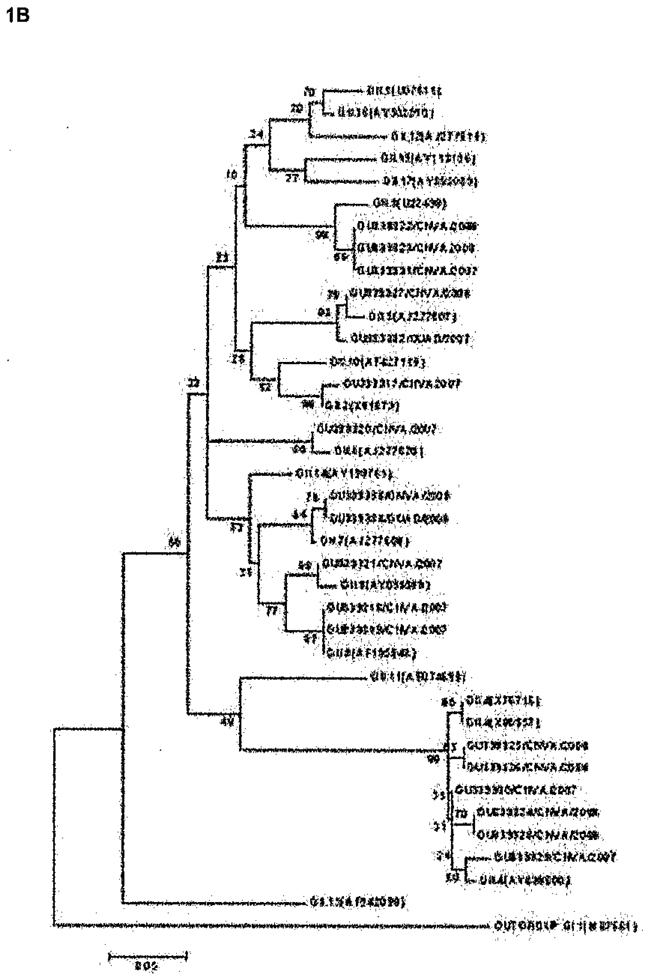

Of the 30 diarrheal stool samples identified as NoV-positive, 12 belonged to GI (40%) while 18 belonged to GII (60%). Results obtained from the analysis of the partial amino acid (AA) capsid sequence of the most conserved region of the capsid protein suggested a diverse population of NoV strains in the study area. As shown in Figure 1, NoVs matching four different (1A) GI clusters (GI.1, GI.3, GI.5 and GI.8) and 8 different (1B) GII clusters (GII.2, GII.3, GII.4, GII.5, GII.6, GII.7, GII.8 and GII.9) were identified.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of (A) GI and (B) GII NoV strains identified from subjects with travelers’ diarrhea in Mexico based on partial AA sequences of the NoV capsid gene. Samples are listed by accession number (GU339305-GU339334) followed by the location (GUAD=GuadaIajara and CNVA=Cuernavaca) and year of collection. Reference sequences are labeled by their classification followed by their accession number in parenthesis and were described by Zheng et al [27]. Percentage bootstrap values are shown at the branch nodes. The scale indicates nucleotide substitutions per site.

Phylogenetic analysis of nucleotide sequences was carried out for NoV cases by season and location. All GI NoV-TD cases were identified during 2007. A single GI.8 strain was found to cause disease in 9 different travelers in two cities during the same season. Only one positive sample was recovered from a traveler during spring. Four different GII.4 strains were associated with 6 NoV-TD cases in travelers to Cuernavaca. In Guadalajara, 4 travelers had GI NoV-TD (3 GI.8 and 1 GI.3) and one traveler had a GII virus (GII.5). All 11 episodes of diarrhea observed during the winter months were associated with viruses belonging to GII while all 12 of the GI strains identified were isolated from patients who had traveled during the summer months of 2007. All the NoV-positive samples collected during 2008 belonged to GII Furthermore, the GII.4 strains identified in the present study appeared to be related to the epidemic strain 2006b that peaked in 2006–2007, and another GII.4 sample was closely related to 2006a, the other epidemic strain seen during 2006–2007 (data not shown).

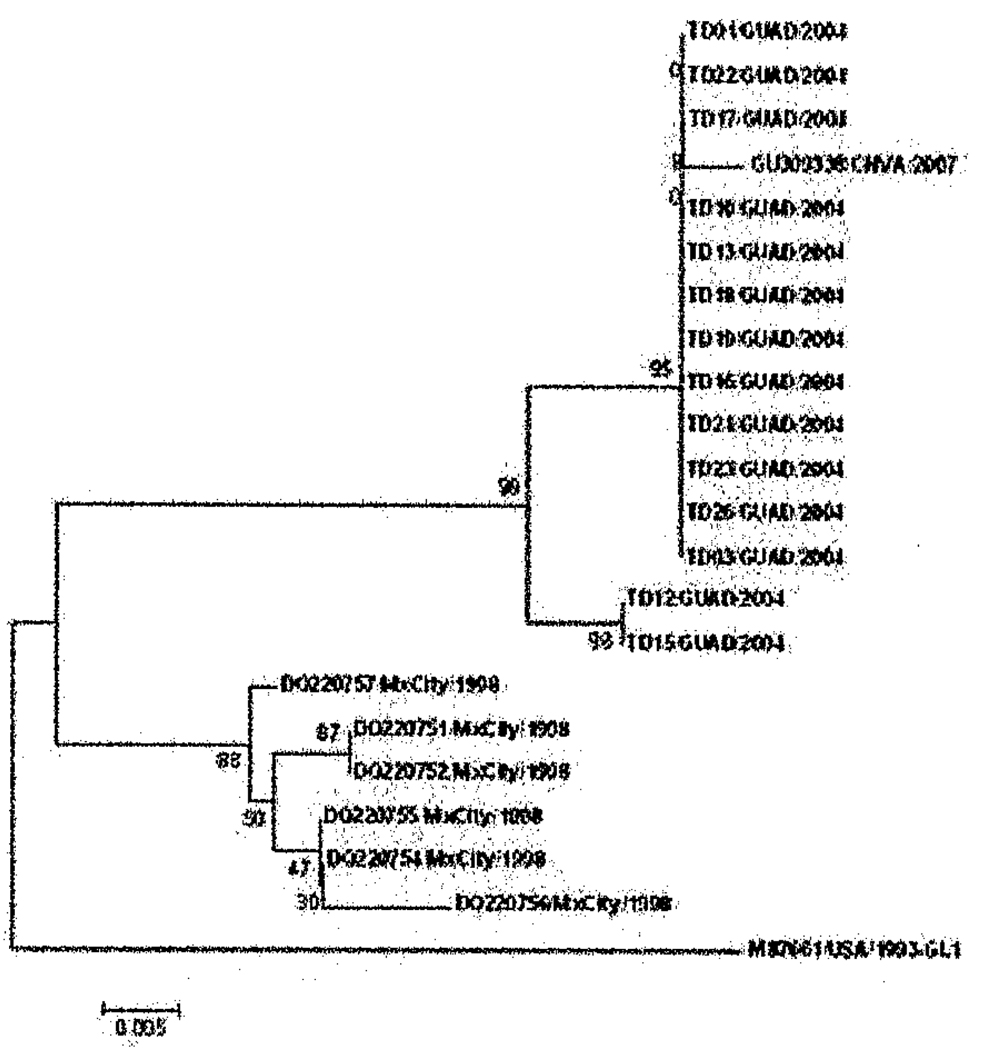

Partial capsid sequence alignment of the GI.1 strain described in the present study showed a high degree of similarity with a subset of GI.1 viruses previously identified among a population of travelers to Guadalajara, Mexico in 2004 [19]. Less similarity was observed with other GI.1 strains identified among a pediatric population living in a peri-urban location located along the eastern perimeter of Mexico City [28] (Figure 2), which shows strain diversity across time.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of NoV based on partial capsid nucleotide sequences of GI.1 strains detected in 3 Studies. Samples are listed by accession number or study number followed by the location (MxCity=Mexico City, GUAD=Guadalajara and CNVA=Cuernavaca) and year of collection. Norwalk virus reference strain is listed as M87661/USA/1993/GI.1 [44]. Sequences listed as TD followed by sample number, location and year were provided by Dr. GwangPyo Ko [19] and sequences listed by accession number DQ220751 to DQ220757 were taken from Garcia et al [28]. Percentage bootstrap values are shown at the branch nodes. The scale indicates nucleotide substitutions per site.

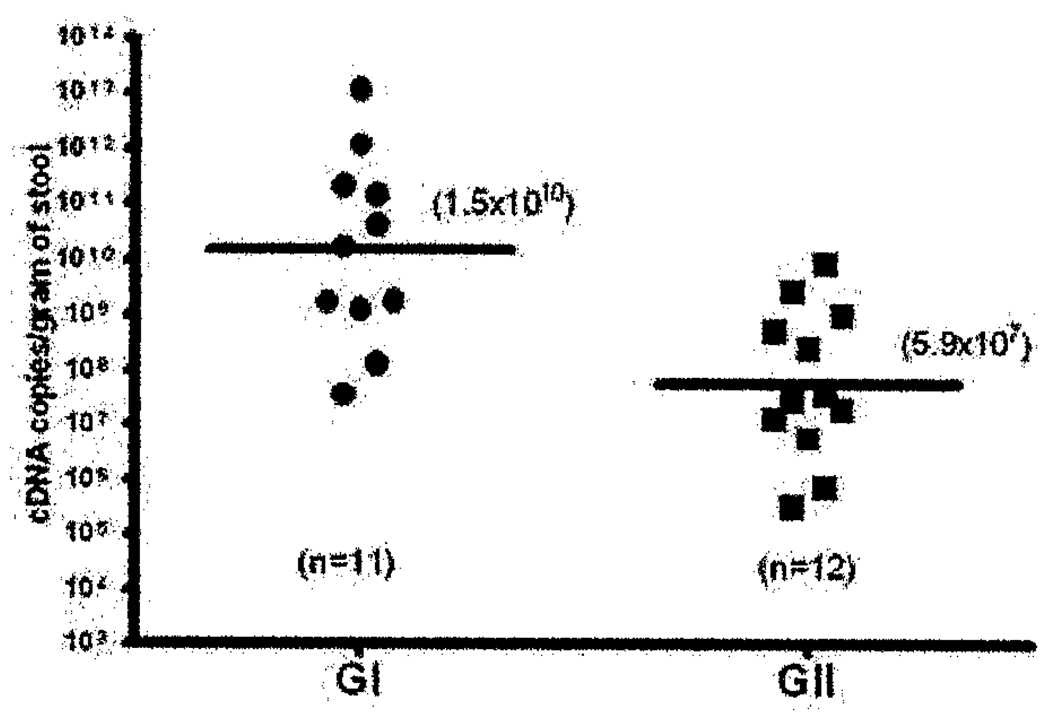

NoV cDNA viral loads among affected travelers

The median cDNA viral load of NoV GI (n=11) and GII (n=12) detected in the fecal specimens was 1.73×1010 (range 3.76 × 107–1.18×1013) and 3.43×107 (range 3.26×105 – 8.93×109) genome copies per gram of fecal specimen, respectively (Figure 3). The median GI NoV fecal shedding was found to be ≥500-fold higher than that of GII (p=0.003). Similar results were observed when NoV-si GI (n=3) was compared to NoV-si GII (n=5) (p=0.036) (data not shown). No statistical difference was observed when GI/GII NoV-si (n=8) and GI/GII NoV-co (n=9) were compared (p=0.962). Additionally, individual analysis by NoV genogroup and the presence or absence of co-pathogens did not show any statistical difference. GI NoV-si vs. GI NoV-co, p=0.7213 and GII NoV-si vs. GII NoV-co, p=0.6905. These results suggest that NoVs may play a role in the development of the disease. Furthermore, analysis of severity of clinical symptoms with intensity of cDNA viral load did not show associations (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Scatterplot for cDNA viral load of noroviruses genogroup I (GI) and GII representing all isolates. The bars represent the geometric mean of cDNA viral loads.

Discussion

In line with our previous results that NoV are a significant agent of TD [19, 20], the study reported herein has shown a prevalence rate of 9% for travelers to Mexico experiencing NoV-associated diarrhea. Although the prevalence rate observed here is lower than that reported in previous years [18–20], this study represents a multi-seasonal analysis of travelers during two consecutive years in three different locations. The role of NoVs in travelers’ illness could be even greater since stool samples collected and analyzed in the present study were only from travelers with acute diarrhea and not from travelers who had a vomiting illness and no diarrhea as the presentation of their gastroenteritis. This observation should be taken into consideration for further studies of the true NoV prevalence among ill travelers since the onset of vomiting and the absence of diarrhea can be seen after NoV infection [30].

Consistent with previous reports where NoV infection have been referred to as “winter-vomiting disease” [31], the highest prevalence of NoV infections occurred from December to February, which is considered the winter season in Mexico, and where GII.4 strains were responsible for 55% of the cases which correlates with previously published data where winter outbreaks were primarily due to GII.4 strains [32, 33]. However, it is important to mention that only during the winter of 2008 in Cuernavaca we observed a higher prevalence rate of NoV than in other seasons. Interestingly, all the NoV-TD episodes observed during the winter months were associated with viruses belonging to GII while all the GI strains identified were isolated from patients who had traveled during the summer months of 2007.

As observed in the past (unpublished data) and in this present study, travelers to Cuernavaca are usually more commonly affected by NoV-diarrhea than those who travel to Guadalajara. A possible explanation might be that Cuernavaca is closer to the most populated city in Mexico, Mexico City and is occupied by a large population of people who commute to Mexico City on a daily basis, while Guadalajara is a larger urban city inhabited by people who usually don’t commute to other cities to work, thus decreasing the possibilities of introduction of new pathogens into the community.

In line with previous reports [18, 19], we observed a strong and diverse presence of GI viruses despite the predominance of GII 4 viruses in most outbreaks [34–41]. Although our results demonstrate a great diversity of NoV strains affecting travelers, where 40% (12/30) belonged to GI and 60% (18/30) belonged to GII, an outbreak caused by a single GI.8 virus affected 9 different travelers during the summer months of 2007 in both cities, which corresponded to 75% of the NoV-TD cases attributed to GI viruses.

In this study we show that the median cDNA viral load of NoV GI is ≥500-fold higher than that of GII in fecal specimens of travelers with NoV-TD. Differences in viral loads may be caused by experimental and host variables including time of sample collection after infection, affinity of annealing of primers and probes to diverse viral genome sequences, age of the affected person, host immune response and course of infection. However, based on our results we speculate that the increase cDNA viral load observed in NoV-GI specimens have an impact in the transmission of these strains among susceptible hosts through the fecal-oral route partially explaining the continuous presence of GI strains in travelers to these locations as previously reported by our group and others [18, 19].

The majority of clinical symptoms reported by NoV-TD patients did not differ from the symptoms that have been reported for TD caused by other common bacterial pathogens [19, 42, 43], nonetheless vomiting was more often associated with NoV-single infections.

This study demonstrates that the vast diversity of NoVs found among travelers to Mexico play an important role in travelers’ health posing a challenge for vaccine development. Prevention methods such as vaccinations should focus on eliciting cross-reacting antibodies that will protect individuals against a diverse population of NoVs since natural infection could implicate the presence of co-circulating strains, as shown in this study.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Kazuhiko Katayama at the National Institute of Infectious Diseases in Tokyo, Japan for providing us with NoV GI and GII plasmid controls. We also thank Dr. Rainer Lanz, Dr. Mary Estes, Dr. Wendy Keitel, Tyler Sharp, Sasirekha Ramani and Fred Neill at Baylor College Medicine, and Dr. Pablo Okhuysen and Lily Carlin at the University of Texas, Health Science Center for their support and helpful discussion.

Funding was provided by discretionary funds from the University Of Texas School Of Public Health, Center for Infectious Disease and in part by grants from Public Health Service (grant DK 56338) which funds the Texas Gulf Coast Digestive Diseases Center, Houston, Texas. Also by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases K23 DK084513-02 awarded to HLK.

Financial Support: The study was supported by discretionary funds at the Center for Infectious Diseases, University of Texas School of Public Health

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts to report.

References

- 1.Green KY, Ando T, Balayan MS, et al. Taxonomy of the caliciviruses. J Infect Dis. 2000 May;181 Suppl 2:S322–S330. doi: 10.1086/315591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green SM, Lambden PR, Caul EO, Ashley CR, Clarke IN. Capsid diversity in small round-structured viruses: molecular characterization of an antigenically distinct human enteric calicivirus. Virus Res. 1995 Aug;37(3):271–283. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00041-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliver SL, Dastjerdi AM, Wong S, et al. Molecular characterization of bovine enteric caliciviruses: a distinct third genogroup of noroviruses (Norwalk-like viruses) unlikely to be of risk to humans. J Virol. 2003 Feb;77(4):2789–2798. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.4.2789-2798.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daniels NA, Bergmire-Sweat DA, Schwab KJ, et al. A foodborne outbreak of gastroenteritis associated with Norwalk-like viruses: first molecular traceback to deli sandwiches contaminated during preparation. J Infect Dis. 2000 Apr;181(4):1467–1470. doi: 10.1086/315365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glass RI, Parashar UD, Estes MK. Norovirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med. 2009 Oct 29;361(18):1776–1785. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel MM, Widdowson MA, Glass RI, Akazawa K, Vinje J, Parashar UD. Systematic literature review of role of noroviruses in sporadic gastroenteritis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008 Aug;14(8):1224–1231. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.071114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutierrez MF, Alvarado MV, Martinez E, Ajami NJ. Presence of viral proteins in drinkable water--sufficient condition to consider water a vector of viral transmission? Water Res. 2007 Jan;41(2):373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riordan T, Craske J, Roberts JL, Curry A. Food borne infection by a Norwalk like virus (small round structured virus) J Clin Pathol. 1984 Jul;37(7):817–820. doi: 10.1136/jcp.37.7.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yee EL, Palacio H, Atmar RL, et al. Widespread outbreak of norovirus gastroenteritis among evacuees of Hurricane Katrina residing in a large "megashelter" in Houston, Texas: lessons learned for prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Apr 15;44(8):1032–1039. doi: 10.1086/512195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green KY, Belliot G, Taylor JL, et al. A predominant role for Norwalk-like viruses as agents of epidemic gastroenteritis in Maryland nursing homes for the elderly. J Infect Dis. 2002 Jan 15;185(2):133–146. doi: 10.1086/338365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koo HL, Ajami NJ, Jiang ZD, Atmar RL, DuPont HL. Norovirus infection as a cause of sporadic healthcare-associated diarrhoea. J Hosp Infect. 2009 Jun;72(2):185–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koo HL, Ajami NJ, Jiang ZD, et al. A nosocomial outbreak of norovirus infection masquerading as clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Apr l;48(7):e75–e77. doi: 10.1086/597299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Widdowson MA, Cramer EH, Hadley L, et al. Outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis on cruise ships and on land: identification of a predominant circulating strain of norovirus--United States, 2002. J Infect Dis. 2004 Jul 1;190(1):27–36. doi: 10.1086/420888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kendrick MA. Study of illness among Americans returning from international travel, July 11-August 24, 1971. (preliminary data) J Infect Dis. 1972 Dec;126(6):684–685. doi: 10.1093/infdis/126.6.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kendrick MA. Summary of study on illness among Americans visiting Europe, March 31,1969–March 30, 1970. J Infect Dis. 1972 Dec;126(6):685–687. doi: 10.1093/infdis/126.6.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steffen R, Sack DA, Riopel L, et al. Therapy of travelers' diarrhea with rifaximin on various continents. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 May;98(5):1073–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang ZD, Lowe B, Verenkar MP, et al. Prevalence of enteric pathogens among international travelers with diarrhea acquired in Kenya (Mombasa), India (Goa), or Jamaica (Montego Bay) J Infect Dis. 2002 Feb 15;185(4):497–502. doi: 10.1086/338834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapin AR, Carpenter CM, Dudley WC, et al. Prevalence of norovirus among visitors from the United States to Mexico and Guatemala who experience traveler's diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2005 Mar;43(3):1112–1117. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.3.1112-1117.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ko G, Garcia C, Jiang ZD, et al. Noroviruses as a cause of traveler's diarrhea among students from the United States visiting Mexico. J Clin Microbiol. 2005 Dec;43(12):6126–6129. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.12.6126-6129.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koo HL, Ajami NJ, Jiang Z-D, Neill FH, Atmar RL, Ericsson CD, Okhuysen PC, Taylor DN, Bourgeois AL, Steffen R, DuPont HL. Norovirus as a Cause of Diarrhea in Travelers to Guatemala, India and Mexico. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010 doi: 10.1128/JCM.02072-09. published online ahead of print on 19 March 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson AD, Garrett VD, Sobel J, et al. Multistate outbreak of Norwalk-like virus gastroenteritis associated with a common caterer. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Dec 1;154(11):1013–1019. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.11.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kojima S, Kageyama T, Fukushi S, et al. Genogroup-specific PCR primers for detection of Norwalk-like viruses. J Virol Methods. 2002 Feb;100(1–2):107–114. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(01)00404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987 Jul;4(4):406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuckerlandl E, Pauling L. Evolutionary divergence and convergence in proteins. In: Bryson V, voguel HJ, editors. Evolving Genes and Proteins. New York: Academic Press; 1965. pp. 97–166. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007 Aug;24(8):1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootsrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng DP, Ando T, Fankhauser RL, Beard RS, Glass RI, Monroe SS. Norovirus classification and proposed strain nomenclature. Virology. 2006 Mar 15;346(2):312–323. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia C, DuPont HL, Long KZ, Santos JI, Ko G. Asymptomatic norovirus infection in Mexican children. J Clin Microbiol. 2006 Aug;44(8):2997–3000. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00065-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kageyama T, Kojima S, Shinohara M, et al. Broadly reactive and highly sensitive assay for Norwalk-like viruses based on real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2003 Apr;41(4):1548–1557. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1548-1557.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atmar RL, Opekun AR, Gilger MA, et al. Norwalk virus shedding after experimental human infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008 Oct;14(10):1553–1557. doi: 10.3201/eid1410.080117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adler JL, Zickl R. Winter vomiting disease. J Infect Dis. 1969 Jun;119(6):668–673. doi: 10.1093/infdis/119.6.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroneman A, Verhoef L, Harris J, et al. Analysis of integrated virological and epidemiological reports of norovirus outbreaks collected within the Foodborne Viruses in Europe network from 1 July 2001 to 30 June 2006. J Clin Microbiol. 2008 Sep;46(9):2959–2965. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00499-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verhoef L, Depoortere E, Boxman I, et al. Emergence of new norovirus variants on spring cruise ships and prediction of winter epidemics. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008 Feb;14(2):238–243. doi: 10.3201/eid1402.061567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruggink L, Marshall J. Molecular changes in the norovirus polymerase gene and their association with incidence of GII.4 norovirus-associated gastroenteritis outbreaks in Victoria, Australia, 2001–2005. Arch Virol. 2008;153(4):729–732. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dominguez A, Torner N, Ruiz L, et al. Aetiology and epidemiology of viral gastroenteritis outbreaks in Catalonia (Spain) in 2004–2005. J Clin Virol. 2008 Sep;43(1):126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho EC, Cheng PK, Lau AW, Wong AH, Lim WW. Atypical norovirus epidemic in Hong Kong during summer of 2006 caused by a new genogroup II/4 variant. J Clin Microbiol. 2007 Jul;45(7):2205–2211. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02489-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okada M, Ogawa T, Yoshizumi H, Kubonoya H, Shinozaki K. Genetic variation of the norovirus GII-4 genotype associated with a large number of outbreaks in Chiba prefecture, Japan. Arch Virol. 2007;152(12):2249–2252. doi: 10.1007/s00705-007-1028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siebenga J, Kroneman A, Vennema H, Duizer E, Koopmans M. Food-borne viruses in Europe network report: the norovirus GII.4 2006b (for US named Minerva-like, for Japan Kobe034-like, for UK V6) variant now dominant in early seasonal surveillance. Euro Surveill. 2008 Jan 10;13(2) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siebenga JJ, Vennema H, Duizer E, Koopmans MP. Gastroenteritis caused by norovirus GGII.4, The Netherlands, 1994–2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007 Jan;13(1):144–146. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.060800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siebenga JJ, Vennema H, Zheng DP, et al. Norovirus illness is a global problem: emergence and spread of norovirus GII.4 variants, 2001–2007. J Infect Dis. 2009 Sep 1;200(5):802–812. doi: 10.1086/605127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tu ET, Bull RA, Greening GE, et al. Epidemics of gastroenteritis during 2006 were associated with the spread of norovirus GII.4 variants 2006a and 2006b. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Feb l;46(3):413–420. doi: 10.1086/525259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DuPont HL. Therapy for and prevention of traveler's diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Jul 15;45 Suppl l:S78–S84. doi: 10.1086/518155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor DN, Bourgeois AL, Ericsson CD, et al. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter study of rifaximin compared with placebo and with ciprofloxacin in the treatment of travelers' diarrhea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006 Jun;74(6):1060–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang X, Wang M, Wang K, Estes MK. Sequence and genomic organization of Norwalk virus. Virology. 1993 Jul;195(1):51–61. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]