Abstract

Recent research shows that poor marital quality adversely affects trajectories of physical health over time and that these adverse effects are similar for men and women. These studies test the possibility of gender differences in vulnerability to poor marital quality, but they fail to take into account possible gender differences in exposure to poor marital quality. We present longitudinal evidence to show that although the impact of marital quality on physical health trajectories may be similar for married men and women, generally lower levels of marital quality experienced by women may translate into a sustained disadvantage for the health of married women over the life course. These findings frame the call for renewed theoretical work on gender and marriage that takes into account both gender similarity in response to marital quality as well as gender differences in the experience of marriage over the life course.

Marital quality is a multidimensional concept that includes positive experiences such as feeling loved, cared for, and satisfied in the relationship as well as negative experiences such as demands from one’s spouse and marital conflict. A few studies find no gender difference on some measures of marital quality, although most studies find lower levels of marital quality for women on most measures (e.g., Rogers & Amato, 2000). The few studies that consider how marital quality changes over time conclude that marital quality tends to decline over time (positive dimensions decline and negative dimensions increase) in a similar fashion for men and women even though women have lower baseline levels of marital quality (Umberson, Williams, Powers, Chen, & Campbell, in press; VanLaningham, Johnson, & Amato, 2001). Notably, we find no studies that report poorer marital quality states or trajectories for men than for women—no matter how marital quality is defined.

Recent research shows that marital quality is associated with physical health in the general population and in clinical studies (for a review, see Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, in press). Several of these studies address the possibility that the health of women is more vulnerable to poor marital quality than is the health of men. Clinical and laboratory-based studies tend to find evidence of female vulnerability to poor marital quality, whereas population-based longitudinal studies on the general health consequences of both positive and negative dimensions of marital quality fail to reveal a gender difference. All of these studies focus on the issue of gender vulnerability and do not take into account that women may be exposed to lower levels of marital quality relative to men. If this is the case, then studies concluding that there is no gender difference in the impact of marital quality on health may be overemphasizing the issue of vulnerability and underemphasizing basic gender differences in exposure to low levels of marital quality. Moreover, gender differences in exposure to marital difficulties may be more exaggerated at certain points in the life course—for example, early in the marital life course when young children are more likely to be in the home or late in the life course when health and disability become more likely. If women sustain a lower level of marital quality relative to men over the life course, this may ultimately translate into a significant health disadvantage for married women. We use growth-curve analysis to consider how gender and age jointly predict trajectories of change in one dimension of marital quality over time. In addition, we illustrate how gender differences in that measure may contribute to gender inequity in physical health over the life course.

Background

Gender and Marital Quality Over the Life Course

Women typically report lower marital quality than do men in national surveys—even taking into account different measures of marital quality (e.g., Umberson, Chen, House, Hopkins, & Slaten, 1996). Very little attention has been directed to the possibility that gender differences in marital quality might depend on life-course position even though there are several reasons to expect this to be the case. Although space constraints do not permit a full review of the literature here, we suggest at least two reasons to expect gender and life course variation in marital quality. First, marital and family roles that contribute to marital quality vary over the life course. For example, marital roles differ for men and women with women shouldering the brunt of household and childcare responsibilities and typically possessing less power and authority than men in their marital relationships (Spain & Bianchi, 1996). In turn, childcare and household duties tend to undermine marital quality (Frisco & Williams, 2004; Greenstein, 1995; Suitor, 1991). If the household division of labor equalizes somewhat with age, perhaps as children grow up and leave the parental home, this might contribute to less pronounced gender differences in marital quality with advancing age. Second, developmental and structural change may occur over time so that couples become more similar in their attitudes, beliefs, roles, and behaviors as they age (Carstensen, Gottman, & Levenson, 1995; Davey & Szinovacz, 2004; Dorfman, 1992). For example, relationships may become more central to men’s lives after they retire so that men and women place increasingly similar emphasis on the importance of close relationships. If this is the case, then sources of difference and conflict in marital relationships may diminish as men and women age.

Marital Quality and Physical Health

Previous research on gender and marital quality considers both positive and negative dimensions of marital quality and, theoretically, either dimension could affect health. Positive marital quality might benefit health by promoting positive health behavior, enhancing mental health, or boosting immune functioning (Robles & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003). Negative marital quality—or marital strain—might adversely affect health because strain leads to poorer health behavior, undermines mental health, or compromises immune functioning (Robles & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003).

Most of the research on marital quality and health falls into one of two categories: (1) laboratory-based and clinical studies and (2) general population surveys. Many studies conducted in laboratory settings at least indirectly support the possibility that poor marital quality undermines physical health. These studies often stage marital conflict between couples and then gauge physiological arousal during conflict. These results consistently suggest that physiological changes occur during marital conflict, that marital conflict can impair immune response, and that marital conflict increases cardiovascular reactivity—all factors that may undermine physical health in the long run (see a review in Robles & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003). A number of these studies also conclude that women exhibit greater physiological arousal in response to marital conflict than do men (Robles & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003). A few prospective studies that follow clinical samples over time also suggest a possible link between gender, marital quality, and health. For example, Coyne and colleagues (2001) studied 189 patients with congestive heart failure. They found that marital quality (with measures focused primarily on positive dimensions of marital quality) predicted 4-year survival and that this effect was stronger for women than men (i.e., lower marital quality was more predictive of mortality among women). Taken together, laboratory studies and research on clinical samples suggest that marital quality may be more important to the health of women than men.

A few longitudinal studies consider the possibility of gender differences in the link between marital quality and health in larger, more representative populations. Longitudinal studies based on a rural Iowa community sample suggest that marital quality (based on a single composite measure that takes into account positive aspects of marital quality and marital stability) protects against physical illness (Wickrama, Lorenz, Conger, & Elder, 1997) as well as the onset of hypertension (Wickrama, Lorenz, Wallace, Peiris, Conger, & Elder, 2001). Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, and Needham (in press) analyze national longitudinal data and find that marital strain (a negative dimension of marital quality) adversely affects physical health trajectories over time. Contrary to most of the laboratory-based and clinical research, the Wickrama studies and the Umberson study find similar effects for men and women. In addition, Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, and Needham (in press) find that the impact of marital strain on health is greater at older ages than at younger ages for both men and women.

Studies that consider the possibility of gender differences in the link between marital quality and health are based on the assumption of gender equality in exposure to the positive and negative dimensions of marital quality (statistically controlling for gender and baseline levels of marital quality). Moreover, they do not consider that gender differences in exposure to positive and negative aspects of marital quality may vary over the life course. In our previous work (Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, in press), we examined two dimensions of marital quality in relation to health: (1) positive marital experiences, tapping into feelings of love, support, and satisfaction, and (2) negative marital experiences, tapping into marital strains. Only the negative dimension of marital quality—marital strain—significantly predicted subsequent trajectories of physical health; that measure is the focus of the present analysis. We build on previous research to assess: (1) the possibility of gender differences in exposure to marital strain over the life course, and (2) whether there is a relative disadvantage to women in the long-term impact of marital strain on trajectories of physical health.

Data and Methods

We analyzed data from three waves of the Americans’ Changing Lives Study, a national panel survey conducted in the United States. Our analytic subsample is composed of the 1,049 individuals who were continuously married across three waves of data (1986, 1989, 1994) and either non-Hispanic white or African American. For additional information on data, measures, and analytic techniques, please see Umberson, Williams, Powers, Chen, and Campbell (2005).

Measures

Marital strain is a latent variable composed of two items that tap into feeling bothered and upset by one’s marriage and having unpleasant conflicts or disagreements (factor determinancy coefficients are .817, .778, and .815 for T1, T2, and T3 marital strain, respectively). Physical health status is based on a measure of self-rated physical health status (excellent, good, fair, or poor). This measure exhibits substantial reliability and validity in national data (Idler & Benyamini, 1997). All analyses include the covariates of sex (1 = male), age, age-squared, race (1 = African American), education, and income.

Methods

In the first part of the study, we used growth-curve analysis to estimate the impact of gender and age differences on initial levels of marital quality as well as the rate of change in marital quality over time. In the second part of the study, we used growth-curve analysis to estimate the impact of gender and age differences in the impact of marital strain on initial levels of physical health and the rate of change in physical health over time.

Results

Gender, Age, and Marital Quality

Our growth-curve results indicate that, in models with no covariates, marital strain tends to increase over time for the sample as a whole (see also Umberson, Williams, Powers, Chen, & Campbell, 2005). As shown in Table 1, models with covariates reveal a significant interaction between gender and age in predicting initial levels of marital strain. Among young married individuals (approximately age 30 and younger), men and women report similar levels of marital strain. But after about age 40, women report more marital strain than do men, and this gender difference is greater at older ages. These models also indicate a significant interaction between gender and age-squared in predicting the rate of change in negative experience over time. Women exhibit a fairly linear rate of increase in marital strain over the study period, regardless of age (although baseline levels of marital strain are higher for younger women), but men exhibit a steeper increase in marital strain than do women up to about age 60. After age 60, men experience almost no change in marital strain. Overall, our results suggest the following: (1) overall levels of marital strain are lower in older age cohorts, (2) the general trend is for marital strain to increase over time for all age cohorts, (3) in middle age, men experience a more rapid increase in marital strain than do women, (4) at most ages, women exhibit higher levels of marital strain than do men, and (5) the gender difference is greatest in the oldest age group, with men experiencing substantially lower levels of marital strain and minimal change in marital strain over the 8-year study period.

Table 1.

Estimated Effects of Life Course and Sociodemographic Characteristics on Marital Strain from Linear Growth Curve Model (N = 1,049)

| Independent Variables | Marital Strain

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent Intercept

|

Latent Slope

|

|||

| Est. | SE | Est. | SE | |

| 1986 life course | ||||

| Age (in 10 year and centered at 4.93) | −.033** | .012 | .001 | .001 |

| Age × Gender | −.036* | .017 | −.002 | .001 |

| Age squared | — | — | .000 | .001 |

| Age squared × Gender | — | — | −.002* | .001 |

| Sociodemographic controls | ||||

| Gender (Male = 1) | −.044† | .025 | .004 | .003 |

| Race (Black = 1) | .090* | .033 | .000 | .003 |

| Education | .010† | .005 | .000 | .000 |

| Household income (10,000) | −.001 | .001 | .000 | .000 |

| Previous divorce | .040 | .033 | .009*** | .003 |

| Means of growth parameters | −.092 | .062 | .012* | .005 |

| Variances in growth parameters | .159*** | .007 | .000*** | .000 |

| R2 | .056 | .044 | ||

Notes: Two-tailed tests:

p < .1;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

— = Parameter not in model because of insignificance; SE = standard error.

Implications for Health

In a recent study, we estimated growth-curve models to assess the effects of marital strain on the initial level and trajectory of change in self-assessed health over time (Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, in press). Our results indicate that marital strain is associated with diminished physical health over time and that the adverse effect of marital strain on physical health is significantly stronger with advancing age. We found no evidence for a sex difference in the adverse effect of marital strain on health. However, our results did not explore the implications of a gender difference in exposure to marital strain and what such a difference might mean to physical health over time.

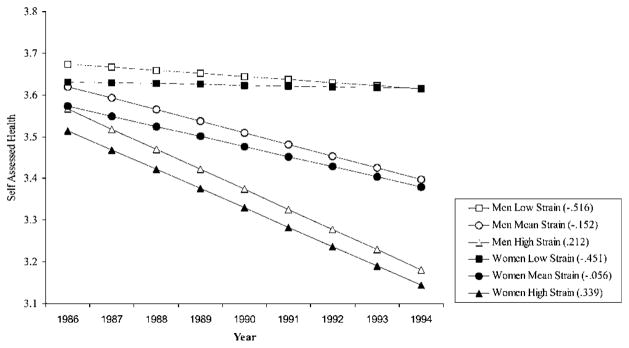

In Figure 1, we used the results from our recent work (Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, in press) to plot predicted trajectories of physical health among married 70-year-olds separately for men and women at gender-specific low, average, and high levels of marital strain. Thus, these trajectories reflect a pattern in which women at midlife and older begin the study with higher average levels of marital strain than do men at the same ages. We present trajectories for 70-year-old adults because the health consequences of marital strain for health are greater at older ages. This figure illustrates that, among 70-year-olds, men and women with the lowest levels of marital strain exhibit the least change in physical health over time. Men and women at the mean level of marital strain exhibit a moderate decline in health over time. Those men and women with the highest levels of marital strain experience the greatest decline in health. The self-assessed health of men and women is most similar at the lowest level of marital strain and most divergent at the highest level of marital strain. This gender divergence occurs not because women are more vulnerable to marital strain but because the initial level of marital strain is higher for women than men and this difference is sustained over time.

Figure 1.

Estimated trajectories of self-assessed health by marital strain and gender: U.S. married adults age 70. Note: Trajectories plotted using age- and gender-specific means and standard deviations of Time 1 marital strain.

Discussion

Recent research indicates that marital strain increases over time and that this increase is very similar for men and women (Umberson, Williams, Powers, Chen, & Campbell, 2005). In addition, marital strain is associated with a decline in health over time, and this decline is greater at older ages and similar for men and women (Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, in press). All in all, these findings make it appear that women are not more vulnerable than men when it comes to change in marital strain over time or in the impact of marital strain on health. This conclusion, however, fails to emphasize that men and women are not equal when it comes to exposure to marital strain.

Although one might expect greater gender differences in marital strain at younger ages—when childcare responsibilities tend to fall more heavily on women’s shoulders, this is not what we find. Rather, until about age 30, men and women are fairly similar in their levels of marital strain as well as the rate of increase in marital strain over time. We find that, after about age 40, baseline levels of marital strain are higher for women than men, and this gender difference is greater at older ages. Moreover, in later life, women continue to experience a steady increase in marital strain, whereas men experience relative stability in their already lower levels of marital strain. This may give men a substantial relative advantage in later life when marital strain has its strongest effects on physical health status.

A number of factors may contribute to women’s higher levels of marital strain at older ages. Typically, women marry men who are older than themselves. In addition, men experience serious, potentially chronic and fatal illnesses at younger ages than do women. As a result, among older couples, women are much more likely than men to provide care to a sick or disabled spouse; this may impose more burden and, consequently, more marital strain on women. We are currently analyzing qualitative data from an in-depth interview study of couples at various stages of the life course. This analysis strongly suggests that, even among happily married long-term couples, illness of one spouse can impose substantial strain on the marital relationship—not simply from caregiving strain but also from worry and concern about one’s spouse, worry over the future, and loss of previously valued interactions with one’s spouse. Unfortunately, the present findings suggest that marital strain has substantial adverse consequences for the health of the partner who perceives such strain. Additional research is needed to examine the reasons that men and women report marital strain at different points in the life course and to suggest what might be done to alleviate these sources of stress.

Caveats

The data for this study cover an 8-year time span, and we consider how marital strain may have changed over this period of time. Our results indicate that marital strain is higher at younger ages, but they may reflect cohort differences in marital strain. Moreover, gender may be associated with marital strain in different ways for different age cohorts. We are unable to establish the role of cohort effects in affecting the present findings. It is of note that, for all age cohorts, we find that marital strain tends to increase over time. In addition, men and women may differ in the way they typically perceive and report marital strain. Although this possibility cannot be ruled out entirely, we would note that marital strain at any given level seems to affect the physical health of men and women in a similar fashion (see Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, in press). Finally, our past research on marital quality and health has considered a negative and a positive dimension of marital quality and suggests stronger effects of the negative dimension for health (Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, in press). This finding fits with past research showing that the negative aspects of relationships have stronger effects on mental health than do the positive aspects (Umberson et al., 1996). However, theoretical work suggests that both positive and negative aspects of relationships might affect physical health and that future research should include more extensive measures of various dimensions of marital quality in relation to health outcomes.

Conclusion

Recent research suggests that men and women are more similar than different when it comes to the importance of marital quality for health and well being (Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, in press; Wickrama et al., 1997, 2001; Williams 2003). However, this portrait of gender equity may be premature. The present results on physical health highlight the importance of integrating research and theory on gender difference and similarity to illuminate our understanding of gender and health. Men and women experience similar levels of marital strain at younger ages and increasingly divergent levels of marital strain at older ages. Yet, when levels of marital strain are equal, marital strain seems to have similar effects on the physical health of men and women. Our results suggest that the balance of gender differences and similarities may depend on age. As Phyllis Moen (this issue) argues, it may be most useful to develop a life-course perspective that describes the psychosocial factors involved in shaping both exposure and vulnerability to marital and family experiences over the life course.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (RO1 AG17455).

We would like to thank the participants in the conference on Health Inequalities Across the Life Course, Pennsylvania State University, 2004, as well as two anonymous reviewers for their comments on this manuscript.

References

- Carstenson LL, Gottman JM, Levenson RW. Emotional behavior in long-term marriage. Psychology and Aging. 1995;10:140–149. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Rohrbaugh MJ, Shoham V, Sonnega JS, Nicklas JM, Cranford JA. Prognostic importance of marital quality for survival of congestive heart failure. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2001;88:526–529. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01731-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey A, Szinovacz ME. Dimensions of marital quality and retirement. Journal of Family Issues. 2004;25:431–464. [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman LT. Couples in retirement: Division of household work. In: Szinovacz M, Ekerdt DJ, Vinick BH, editors. Families and retirement. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. pp. 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Frisco ML, Williams K. Perceived housework equity, marital happiness, and divorce in dual-earner households. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24:51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein TN. Gender ideology and perceptions of the fairness of the division of household labor: Effects on marital quality. Social Forces. 1995;74:1029–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The physiology of marriage: Pathways to health. Physiology and Behavior. 2003;79:409–416. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ, Amato PR. Have changes in gender relations affected marital quality? Social Forces. 2000;79:731–753. [Google Scholar]

- Spain D, Bianchi S. Balancing act. NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ. Marital quality and satisfaction with the division of household labor across the family life cycle. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Williams K, Powers D, Chen MD, Campbell A. As good as it gets? A life course perspective on marital quality. Social Forces. 2005;84:493–511. doi: 10.1353/sof.2005.0131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Williams K, Powers DA, Liu H, Needham B. You make me sick: Marital quality and health over the life course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700101. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Chen MD, House JS, Hopkins K, Slaten E. The effect of social relationships on psychological well-being: Are men and women really so different? American Sociological Review. 1996;61:837–857. [Google Scholar]

- VanLaningham J, Johnson DR, Amato P. Marital happiness, marital duration, and the U-shaped curve: Evidence from a five-wave panel study. Social Forces. 2001;79:1313–1341. [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KAS, Lorenz FO, Conger RD, Elder GH., Jr Marital quality and physical illness: A latent growth curve analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1997;59:143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KAS, Lorenz FO, Wallace LE, Peiris L, Conger RD, Elder GH., Jr Family influence on physical health during the middle years: The case of onset of hypertension. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:527–539. [Google Scholar]

- Williams K. Has the future of marriage arrived? A contemporary examination of gender, marriage, and psychological well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:470–487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]