Abstract

Objective

A major focus of early intervention research is determining the risk of conversion to psychosis and developing optimal algorithms of prediction. Although reported rates of nonconversion vary in the literature, the nonconversion rate always encompasses a majority (50%–85%) of the sample participants. Less is known about the outcome among this group, referred to as false positive individuals.

Method

A longitudinal study was conducted of more than 300 prospectively identified treatment-seeking individuals meeting criteria for a psychosis-risk syndrome. Participants were recruited and evaluated across eight clinical research centers as part of the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study. Over a 2.5-year follow-up assessment period, 214 (71%) participants had not made the transition to psychosis.

Results

The sample examined included 111 individuals who had at least 1 year of follow-up data available and did not transition to psychosis within the study duration. In year 1, there was significant improvement in ratings for attenuated positive and negative symptoms. However, at least one attenuated positive symptom was still present for 43% of the sample at 1 year and for 41% at 2 years. At the follow-up timepoints, social and role functioning were significantly poorer in the clinical sample relative to nonpsychiatric comparison subjects.

Conclusions

Help-seeking individuals who meet prodromal criteria appear to represent those who are truly at risk for psychosis and are showing the first signs of illness, those who remit in terms of the symptoms used to index clinical high-risk status, and those who continue to have attenuated positive symptoms.

A major focus of schizophrenia research is early detection, particularly during the putative prodromal phase of a psychotic disorder. One recent direction of this research is determining the risk of conversion to full-blown psychosis and developing algorithms of prediction (1–3) of this transition. Participants in such studies meet well-established prodromal criteria (4, 5) and are described as being at ultra high risk or clinical high risk of developing psychosis. In the present study, the term clinical high risk is utilized. Studies typically follow participants for 1 or 2 years. Although reported rates of conversion vary in the literature (1–3, 6, 7), a majority of participants consistently do not develop psychosis during the course of a study. The term false positive (6) has been used to describe such persons. Little, if any, data have been reported about the outcome of these false positive individuals.

The North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study is a consortium of eight research centers that ascertained clinical high-risk individuals and followed them for a period of up to 2½ years (1, 8). Although originally developed as independent studies, the investigations at the eight sites employed similar ascertainment and diagnostic methods, making it possible to form a standardized protocol for mapping data into a new scheme representing the common components across sites (1, 8), yielding one of the largest databases of longitudinally followed clinical high-risk cases worldwide. This data set includes 303 prospectively identified treatment-seeking patients who met criteria for a psychosis-risk syndrome based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (5, 9) and for whom follow-up data were available. Of this sample, 71% had not made the transition to psychosis by the 2.5-year follow-up assessment (1).

The goal of the present study was to determine the clinical and functional status of those who did not convert to psychosis within the time frame of the study. The aims were to 1) examine the change over time in attenuated positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and functional outcome; 2) determine how many participants still met psychosis-risk syndrome criteria at the follow-up time-points and how many still had attenuated positive symptoms; and 3) determine whether those who did not convert to full-blown psychosis developed other disorders. It was predicted that there would be an improvement in attenuated symptoms and that there would be less improvement in functioning.

Method

Sample

Study protocols and informed consent documents, including procedures for data pooling and secondary data analysis, were approved by the institutional review boards of the participating sites (Emory University, Harvard University, University of California Los Angeles, University of California San Diego, University of North Carolina, Universities of Toronto and Calgary, Yale University, and Zucker Hillside Hospital). North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study methods and complete details of the federated database have been described elsewhere (1, 8, 10). Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (5, 9) criteria were used for study entry, and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) was used to assess general psychopathology.

Participants had to meet one of the three established criteria for a psychosis-risk syndrome (11), which are as follows: attenuated psychotic symptom state, brief intermittent psychotic state, and genetic risk with deterioration in functioning. Attenuated psychotic symptom state emphasizes onset or worsening of attenuated positive symptoms in the past 12 months in at least one of the following five symptom domains: unusual thought content, suspicion/paranoia, grandiosity, perceptual anomalies, and disorganized communication. Participants also qualified for a prodromal syndrome if they began displaying (in the past 3 months) brief intermittent positive psychotic symptoms below the threshold required for a DSM-IV axis I psychotic disorder diagnosis or if they possessed a genetic risk for psychosis and displayed deterioration in functioning amounting to a 30% decline in their score on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale in the past 12 months. Genetic risk was defined as a family history of psychosis in first-degree relatives or a diagnosis of schizotypal personality disorder. All North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study sites demonstrated good reliability employing the prodromal criteria (kappa range: 0.80–1.00 across sites) (8, 9).

Criteria for participation in the present study were 1) meeting criteria for a psychosis-risk syndrome, 2) having at least 1 year of follow-up assessment data available, and 3) having not converted to psychosis. We excluded everyone who had ever received anti-psychotic medication either prior to ascertainment or during the course of the study.

A total of 303 participants had at least one follow-up evaluation between the 6- and 42-month duration of the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study. Participants were excluded from the present analyses if they converted to full-blown psychosis anytime after baseline evaluation up until the 2.5-year follow-up assessment (N=89), did not have 1-year follow-up evaluation data available (N=48), or had received antipsychotic medication at some point during the study (N=55). Thus, our final nonconverting sample consisted of 111 individuals (men, N=62; women, N=49). The majority of these participants were Caucasian (82%), with a mean age of 18 years (SD=4.9, range: 12–36). At ascertainment, 48.6% were in high school, 20.7% were in college, 12.6% were unemployed, and 18% were working full- or part-time. In our final sample, all participants met the criteria for the attenuated positive symptom state. This is not unusual, since in clinical high-risk samples only a very small proportion of individuals meet only criteria for a brief intermittent psychotic state or genetic risk with deterioration in functioning (8). Of the 111 individuals in the present sample, 76 had 2-year follow-up evaluation data available. Therefore, we know that 111 did not convert to full-blown psychosis at 1 year, and nested within this group, 76 had not converted by 2 years.

Fifty-five participants (men, N=35, women, N=20) who did not convert to full-blown psychosis but had received treatment with an antipsychotic at some point during the follow-up period were excluded. This group did not differ from the included sample with regard to sex, age, and baseline positive attenuated or negative symptoms as assessed by the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms (9). However, at baseline they had significantly lower scores on the GAF scale (43.52 versus 51.89, t=4.59, p<0.0001) as well as significantly lower ratings on global social (5.98 versus 6.65, t=2.73, p<0.01) and global role (5.91 versus 6.67, t=2.73, p<0.01) functioning assessments compared with the present sample.

The North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study data set also followed a sample of nonpsychiatric comparison subjects (N=139) (8). For the purpose of the present study, we selected 111 who had received social and role functioning assessments and with whom we matched on age and sex to our nonconverting sample.

Measures

Measures used to determine clinical status were the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms, for attenuated positive and negative symptom ratings, and SCID, for axis I and II diagnoses. To assess functioning, we used the GAF scale as well as the Global Functioning: Social and Global Functioning: Role, two new measures of functioning. These measures of global functioning were developed by Cornblatt et al. (12), specifically for the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study project to allow focus on functioning in the putatively prodromal phase of illness (8, 12). These measures have excellent interrater reliability and represent parallel well-anchored scales that account for age and phase of illness, distinguish social from role functioning, and detect functional changes over time (12).

Analyses

Generalized linear mixed models were used to examine the change of symptoms and functioning over 2 years. Independent t tests were used to compare ratings of the clinical high-risk group on the GAF scale and on the two measures of global functioning at the follow-up timepoints with ratings of the nonpsychiatric comparison group to determine whether the high-risk group continued to demonstrate functional impairment.

To determine whether those participants who showed improvement in attenuated symptoms had improved functioning and comorbidity, we divided them into two groups based on whether they did or did not have any of the five positive symptoms rated in the putatively prodromal range on the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms. These two groups were compared on all functioning measures using t tests and on the presence of an axis I diagnosis using chi-square tests.

We used Cochran’s Q test to determine whether there were changes in the proportion of participants presenting with a DSM-IV diagnosis at the different assessment times.

Results

Overall Changes in Symptoms and Functioning

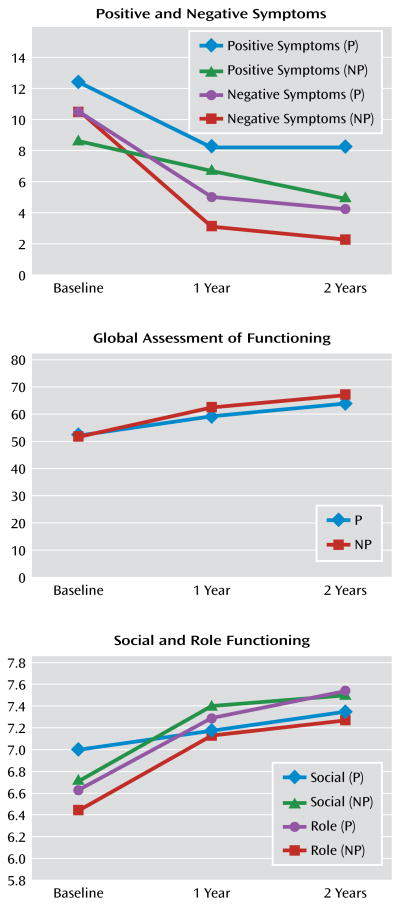

Generalized linear mixed models for repeated-measures data were used to compare the least squares means of positive symptoms, negative symptoms, social functioning, role functioning, and GAF ratings for all participants at baseline, 1 year, and 2 years (Figure 1). Means and standard deviations for these analyses are presented in Table 1. Although there was an improvement over time in both positive and negative symptoms, the improvement was only significant between baseline and 1 year (p<0.0001; p<0.001, respectively), not from 1 year to 2 years. Ratings for social and role functioning improved at each assessment period, but the improvement in both social and role functioning was only significant from baseline to 1 year (p=0.002; p<0.0001, respectively). However, there was a significant improvement in GAF scores between baseline and 1 year as well as between 1 year and 2 years (p<0.0001; p=0.04, respectively) (Table 1).

Figure 1. Symptoms and Functioning Over Time in Patients at Clinical High Risk for Developing Pyschosis, by Prodromal Symptom Statusa.

a Patients were divided into groups according to whether they had a positive symptom rated in the putatively prodromal range (P) or no prodromal positive symptoms (NP).

Table 1.

Symptoms and Functioning Over Time in Patients at Clinical High Risk for Developing Psychosis

| Measure | Timepoint

|

Analysis

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (N=111)

|

1 Year (N=111)

|

2 Years (N=111)

|

Baseline to 1 Year

|

1 Year to 2 years

|

||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | df | t | df | |

| Symptoms | ||||||||||

| Attenuated positive | 11.33 | 3.55 | 5.01 | 3.91 | 4.62 | 3.95 | 15.53*** | 110 | 1.08 | 76 |

| Negative | 9.78 | 6.26 | 5.75 | 5.66 | 4.57 | 5.62 | 6.8*** | 110 | 1.85 | 76 |

| Global Functioning rating | ||||||||||

| Social | 6.66 | 1.56 | 7.13 | 1.43 | 7.30 | 1.56 | −3.37** | 110 | −1.42 | 76 |

| Role | 6.67 | 1.76 | 7.35 | 1.30 | 7.46 | 1.46 | −4.47*** | 110 | −0.88 | 110 |

| Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score | 51.92 | 11.05 | 61.21 | 13.08 | 64.98 | 13.12 | −7.64*** | 110 | −2.87* | 110 |

p<0.05;

p≤0.01;

p<0.0001.

Using independent t tests, we compared our nonconverting sample with the nonpsychiatric comparison group on social and role functioning. Even though we found improved functioning among the nonconverting clinical high-risk participants at each assessment, this group still performed more poorly on both social and role functioning relative to nonpsychiatric comparison subjects. For social functioning, mean and t values at baseline for the clinical high-risk group versus the comparison group were 6.65 (SD=1.51) versus 8.55 (SD=1.01), t=10.76; at 1 year the values were 7.15 (SD=1.43) versus 8.55 (SD=1.01), t=8.25; and at 2 years the values were 7.30 (SD=1.54) versus 8.55 (SD=1.01), t=6.5 (all values significant at p<0.0001). For role function, mean and t values at baseline for the clinical high-risk group versus the comparison group were 6.67 (SD=1.76) versus 8.71 (SD=1.05), t=10.45 (p<0.0001); at 1 year the values were 7.35 (SD=1.30) versus 8.71 (SD=1.05), t=8.31 (p<0.01); and at 2 years the values were 7.30 (SD=1.46) versus 8.71 (SD=1.05), t=6.36 (p<0.01).

Prodromal Diagnostic Criteria

To meet attenuated positive symptom state, the attenuated positive symptoms must have begun or worsened in the past 12 months. Thus, to meet prodromal criteria at the 1-year follow-up assessment, there had to have been an increase in at least one attenuated positive symptom by 1 point. At baseline, 100% of the present nonconverting sample met criteria for attenuated positive symptom state, only six individuals (5.4%) met criteria at 1 year, and six different individuals (5.4%) met criteria at 2 years. Thus, among the nonconverting sample there was a substantial decline in the number of those meeting actual prodromal criteria at the follow-up assessments.

On the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms, a rating of 0–2 indicates that the symptom does not meet criteria for being attenuated; a rating of 3–5 indicates that the symptom is attenuated with different degrees of severity; and a rating of 6 indicates psychotic intensity. At the 1-year follow-up assessment, 45 (42.9%) participants in the present clinical group had at least one attenuated positive symptom (i.e., one of the five attenuated positive symptoms was rated ≥3), and 31 (40.8%) had at least one attenuated positive symptom at 2 years. Those who still had attenuated positive symptoms at 1 year versus those who did not showed no difference in axis I or II diagnoses or social or role functioning at either baseline or the 1-year follow-up assessment.

DSM Axis I and II Diagnoses

Both axis I and II diagnoses were examined. Axis I diagnoses were grouped into the following clusters: any substance use disorder, anxiety disorder, mood disorder, and mania. The percentages of participants that received these diagnoses at each timepoint are presented in Table 2. One individual presented with mania at both the 12- and 24-month follow-up timepoints, and another was diagnosed with mania only at the 12-month follow-up assessment. We used Cochran’s Q test to determine whether the proportions of participants with or without a given diagnosis were the same at the different assessment times. The results demonstrated that there was a statistically significant difference in having anxiety (p<0.0001) or depression (p<0.0001) overall and in having a substance use disorder overall (p=0.02). Pairwise comparisons using a Bonferroni-corrected level of significance (p=0.017) were performed to compare proportions at each timepoint (Table 2).

Table 2.

Axis I Diagnoses Over Time in Patients at Clinical High Risk for Developing Psychosis

| Axis I Diagnosis | Baseline

|

1 Year

|

2 Years

|

Analysis (p)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | Overall | Baseline vs. 1 Year | Baseline vs. 2 Years | 1 Year vs. 2 Years | |

| Anxiety disorder | 59 | 53.15 | 42 | 37.84 | 24 | 31.57 | <0.0001 | 0.001 | <0.0001 | |

| Depression | 39 | 35.14 | 32 | 28.83 | 11 | 14.47 | 0.0001 | <0.05 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Mania | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 1.3 | ||||

| Substance use disorder | 12 | 10.81 | 11 | 9.91 | 3 | 3.9 | 0.011 | <0.01 | ||

Only 71% of the present nonconverting sample (N=79) were assessed for axis II diagnoses. Of this subsample of 79 individuals, 57% (N=45) had no diagnoses at any time, 29% (N=23) had consistent diagnoses (i.e., the same diagnoses at baseline and follow-up assessment), and 14% (N=11) had emerging diagnoses (i.e., met criteria for axis II diagnoses at a follow-up assessment only). Some individuals had more than one diagnosis. Consistent diagnoses were avoidant (N=5), borderline (N=4), schizotypy (N=3), paranoid (N=3), narcissistic (N=1), and obsessive-compulsive (N=1) personality disorders. Emerging diagnoses were avoidant (N=10), paranoid (N=4), borderline (N=3), and obsessive-compulsive (N=1) personality disorders.

Comparison of Participants Who Did and Did Not Remit

There were no differences in age, gender, or social or role functioning between those whose attenuated psychotic symptoms improved and those whose attenuated psychotic symptoms remained. As would be expected, the one exception was that those who still had attenuated positive symptoms had significantly higher ratings for attenuated positive symptoms at baseline (t=2.6, p<0.01).

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to consider the outcome of individuals at clinical high risk of developing psychosis who do not go on to develop a full-blown psychotic illness over a 2½-year period. A recent, small Swiss study demonstrated evidence of transitory attenuated positive symptoms in some individuals who did not convert (13). However, it was unclear whether these young participants improved or whether the baseline presentation of the nonconverting group was predictive of another disorder. Overall, in our study, the nonconverting group demonstrated significant improvement in attenuated positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and social and role functioning. Although symptoms declined significantly in this group overall, this was driven by a subgroup whose symptoms improved over time. Furthermore, more than 50% of this nonconverting sample no longer presented with any attenuated positive symptoms. However, despite a statistically significant improvement in functioning, this group remained at a lower level of functioning than nonpsychiatric comparison subjects. This suggests that initial prodromal categorization is associated with persistent disability, at least for 2.5 years.

Axis I diagnoses tended to diminish in number over time rather than emerge, although a relatively high proportion of clinical high-risk participants did have a mood and/or anxiety disorder. Only a small proportion demonstrated an emerging axis II disorder.

Strengths of this data set are its large sample size and the well-defined criteria for a psychosis-risk syndrome (8). There are also limitations to these data. First, the follow-up evaluation was limited to 1 year and 2 years only. It is likely that a longer follow-up assessment period may have identified additional conversions, particularly since the mean age of this sample at the 1-year follow-up assessment was 19 years and the age of onset of a first episode of psychosis is, on average, 20–24 years (14). Second, the data were originally collected at independently functioning sites not following a common protocol. Third, the outcome measures are constrained by what was common at all sites (8). Fourth, it is possible that some individuals had episodes of transient psychotic-like experiences as reported in the general population (15), but our clinical sample consisted of all help seekers and outcome is mixed in terms of risk status among individuals who do not seek help and are identified in population-based studies as having had psychotic-like experiences (16). Fifth, other medications (e.g., antidepressants) may have had an effect on attenuated positive symptoms. We did not assess this because details of medication status were not universally collected, and for those who were receiving treatment with other medications, dosage and compliance were unknown. However, a study of the entire North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study sample demonstrated that with the same limitations, antidepressant use was not significantly associated with a decline in attenuated positive symptoms (17). Finally, we excluded those individuals who were receiving treatment with antipsychotics, and thus we cannot say how they may have been distributed among the three groups (remission, symptomatic, converted).

In summary, we found that help-seeking individuals who met attenuated positive symptom risk criteria appeared to cluster into several groups over a 2.5-year period. Among the 255 participants with 1 year of follow-up data in the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study, approximately 35% developed a psychotic illness, 24% remitted their attenuated symptoms, 20% retained attenuated positive symptoms at lower levels of severity than those present at baseline, and 21% received an antipsychotic drug while in the prodromal phase and therefore could not be used to represent the natural course. Thus, prodromal attenuated positive symptoms may predict a more severe condition in some but by no means all cases. Thus, better prediction requires a range of both clinical and biological marker-predictors in the future

Overall, our results suggest that persons who meet symptom and functional criteria for a psychosis-risk syndrome represent a collection of the following groups: 1) those who are truly at risk for psychosis and are showing the first signs of disorder, 2) those who remit in terms of the symptoms used to index clinical high-risk status, and 3) those who continue to have attenuated positive symptoms. Future work is needed not only to replicate these findings but to extend them over much longer follow-up periods and with more comprehensive assessments that were beyond the scope of this project.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Addington currently receives (or has received in the past 12 months) investigator-initiated research funding from multiple not-for-profit entities, including the National Institute of Mental Health and the Ontario Mental Health Foundation; she has served as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Pfizer. Dr. Cornblatt currently receives (or has received in the past 12 months) investigator-initiated research funding from not-for-profit entities, including the National Institute of Mental Health and the Stanley Medical Research Institute; she has also served as a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Lilly and has received unrestricted educational grants from Janssen. Dr. Cadenhead currently receives (or has received in the past 12 months) investigator-initiated research funding from the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Cannon currently receives (or has received in the past 12 months) investigator-initiated research funding from multiple not-for-profit entities, including NARSAD, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Staglin Music Festival for Mental Health; he has served as a consultant to Eli Lilly and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. In the past 12 months, Dr. Perkins has received research funding from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, Otsuka, and Pfizer; she has received consulting and educational fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Shire. Dr. Seidman currently receives (or has received in the past 12 months) investigator-initiated research funding from multiple not-for-profit entities, including the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, NARSAD, the National Institute of Aging, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Sidney R. Baer Foundation. Dr. Walker currently receives (or has received in the past 12 months) investigator-initiated research funding from not-for-profit entities, including the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression and the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Woods currently receives (or has received in the past 12 months) investigator-initiated research funding from multiple not-for-profit entities, including the National Institute of Mental Health and the Donaghue, NARSAD, and Stanley foundations; he has received investigator-initiated research funding from multiple for-profit entities, including Bristol-Myers Squibb and UCB Pharma; and he has served as a consultant to Otsuka and Schering-Plough. Dr. Heinssen is employed by the National Institutes of Health. Drs. McGlashan, Tsuang, and Woods report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grants U01 MH-066160 [Dr. Woods], U01 MH0-66134 [Dr. Addington], R01 MH-60720 and K24 MH-76191 [Dr. Cadenhead], R01 MH-065079 [Dr. Cannon], R01 MH-061523 [Dr. Cornblatt], R01 MH-066069 and K23 MH-01905 [Dr. Perkins], R18 MH-43518 [Drs. Tsuang and Seidman], R01 MH-065562 and P50 MH-080272 [Dr. Seidman], R21MH-075027 [Dr. Tsuang], RO1MH-062066 [Dr. Walker], and K05MH01654 [Dr. McGlashan]); the Donaghue Foundation (Dr. Woods); and Eli Lilly (Drs. McGlashan, Addington, and Perkins).

References

- 1.Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, Woods SW, Addington J, Walker E, Seidman LJ, Perkins D, Tsuang M, McGlashan T, Heinssen R. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:28–37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Salokangas RK, Heinimaa M, Linszen D, Dingemans P, Birchwood M, Patterson P, Juckel G, Heinz A, Morrison A, Lewis S, von Reventlow HG, Klosterkotter J. Prediction of psychosis in adolescents and young adults at high risk: results from the Prospective European Prediction of Psychosis Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:241–251. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, Francey SM, McFarlane CA, Hallgren M, McGorry PD. Psychosis prediction: a 12-month follow-up of a high-risk (prodromal) group. Schizophr Res. 2003;60:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yung AR, McGorry PD, McFarlane CA, Jackson HJ, Patton GC, Rakkar A. Monitoring and care of young people at incipient risk of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22:283–303. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Somjee L, Markovich PJ, Stein K, Woods SW. Prospective diagnosis of the initial prodrome for schizophrenia based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes: preliminary evidence of interrater reliability and predictive validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:863–865. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yung AR, McGorry PD. The initial prodrome in psychosis: descriptive and qualitative aspects. Austr N Z J Psychiatry. 1996;30:587–599. doi: 10.3109/00048679609062654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yung AR, Nelson B, Stanford C, Simmons MB, Cosgrave EM, Killackey E, Phillips LJ, Bechdolf A, Buckby J, McGorry PD. Validation of prodromal criteria to detect individuals at ultra high risk of psychosis: 2 year follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2008;105:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, Cornblatt B, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Seidman LJ, Tsuang M, Walker EF, Woods SW, Heinssen R. North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study: a collaborative multisite approach to prodromal schizophrenia research. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:665–672. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Cadenhead K, Cannon T, Ventura J, McFarlane W, Perkins DO, Perlson GD, Woods SW. Prodromal assessment with the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes and the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:703–715. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woods SW, Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, Cornblatt BA, Heinssen R, Perkins DO, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, McGlashen TH. Validity of the prodromal risk syndrome for first psychosis: findings from the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:894–908. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGlashan T, Walsh B, Woods SW. The Psychosis-Risk Syndrome. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornblatt BA, Auther AM, Niendam T, Smith CW, Zinberg J, Bearden CE, Cannon TD. Preliminary findings for two new measures of social and role functioning in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:688–702. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon AE, Umbricht D. High remission rates from an initial ultra-high risk state for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2010;116:168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Addington J, van Mastrigt S, Addington D. Duration of untreated psychosis: impact on 2-year outcome. Psychol Med. 2004;34:277–284. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johns LC, van Os J. The continuity of psychotic experiences in the general population. Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21:1125–1141. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelleher I, Cannon M. Psychotic-like experiences in the general population: characterizing a high-risk group for psychosis. Psychol Med. 2010;19:1–6. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker EF, Cornblatt BA, Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT, Woods SW, Heinssen R. The relation of antipsychotic and antidepressant medication with baseline symptoms and symptom progression: a naturalistic study of the North American Prodrome Longitudinal sample. Schizophr Res. 2009;115:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]