Abstract

Objective To estimate the risks and benefits to health of travel by bicycle, using a bicycle sharing scheme, compared with travel by car in an urban environment.

Design Health impact assessment study.

Setting Public bicycle sharing initiative, Bicing, in Barcelona, Spain.

Participants 181 982 Bicing subscribers.

Main outcomes measures The primary outcome measure was all cause mortality for the three domains of physical activity, air pollution (exposure to particulate matter <2.5 µm), and road traffic incidents. The secondary outcome was change in levels of carbon dioxide emissions.

Results Compared with car users the estimated annual change in mortality of the Barcelona residents using Bicing (n=181 982) was 0.03 deaths from road traffic incidents and 0.13 deaths from air pollution. As a result of physical activity, 12.46 deaths were avoided (benefit:risk ratio 77). The annual number of deaths avoided was 12.28. As a result of journeys by Bicing, annual carbon dioxide emissions were reduced by an estimated 9 062 344 kg.

Conclusions Public bicycle sharing initiatives such as Bicing in Barcelona have greater benefits than risks to health and reduce carbon dioxide emissions.

Introduction

Bicycle sharing schemes have become increasingly popular in countries throughout Europe, Asia, and America to encourage cycling as an alternative means of transport in urban areas.1 Large low cost rental systems (between 1000 and 50 000 bicycles) aimed at encouraging cycling for short urban trips and multimodality (cycling along with another mode of transit) for longer trips have been implemented by cities such as Lyon (2005), Stockholm (2006), Barcelona (2007), Seville (2007), Paris (2007), Toulouse (2007), Hangzhou (2008), Milan (2008), Brussels (2009), Montreal (2009), Mexico City (2010), London (2010), and Guangzhou (2010). In the United States, such large scale initiatives are being considered for Los Angeles and New York. The general impetus for these policies is more often the reduction of traffic congestion than the promotion of health.

Motivated by the growing challenges of global obesity and climate change, international organisations have been calling for multisectoral and multidisciplinary approaches to increase physical activity and reduce reliance on cars.2 3 4 5 In 2005 the European Union formulated an important area of action “addressing the obesogenic environment to stimulate physical activity” (Commission of the European Communities 2005). The Transport Health and Environment, Pan-European Program (THE PEP) provides guidance to policymakers and local professionals on how to encourage cycling and walking along with an instrument, the health economic assessment tool, to estimate the health benefits and cost effectiveness of cycling.6 Similarly, in the United States the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has developed guidelines for the prevention of obesity.3 Integrating the promotion of walking and cycling into daily life (for example, as part of commuting) is a promising way to increase physical activity across a population. Cycling does, however, have some potential risks such as increased road traffic incidents and exposure to air pollution.

We estimated the effect on health of Bicing, the public bicycle sharing initiative in Barcelona, Spain (see web extra appendix). As direct outcomes on health are hard to measure, we estimated the effects by studying all cause mortality using a newly developed health impact model to integrate recently developed tools, existing data from scientific studies, and local data. We focused on the three domains of exposure to air pollution, physical activity, and road traffic incidents. We also estimated the reduction in carbon dioxide emissions.

Methods

Bicing, the public bicycle sharing initiative in Barcelona, Spain, was introduced in March 2007 to improve the use of different types of transport, promote sustainable transport, create a new individual public transport system, promote the bicycle as a common means of transport, improve air quality, and reduce noise pollution. By August 2009, 182 062 people had subscribed to Bicing (11% of the population in Barcelona municipality), with 68% of trips being used for commuting to work or school and 37% combined with another mode of travel. The mean distance travelled by Bicing on a working day was 3.29 km (mean duration 14.1 minutes) and at weekends was 4.15 km (17.8 minutes).7

Framework

We used a health impact assessment framework to estimate the potential effects on health of cycling compared with travel by car (see web extra appendix figure 1). Exposure-response functions were derived from existing studies and calibrated for current exposure and health conditions in Barcelona. We chose to model the effects of all cause mortality due to physical activity, road traffic incidents, and exposure to air pollution based on discussions held among experts during a workshop in Barcelona in 2009 that suggested these domains would have the greatest impact and best available data.8 Recent publications provided further guidance.6 9 10 We focused on residents of Barcelona who started cycling regularly using Bicing after its implementation. Therefore we assessed the additional benefits from physical activity and additional risks due to incremental inhalation of air pollution and increased exposure of new cyclists to road traffic incidents compared with previous exposures as car users. We did not consider the benefits of decreased car use to the general population of Barcelona because of Bicing. We also estimated savings in carbon dioxide emissions.

Table 1 summarises the main input data used in the model. The web extra appendix provides a detailed description of assumptions and calculation steps used to derive the model inputs from available data outlined in this section.

Table 1.

Main input data for model to assess health impact of Bicing initiative in Barcelona, Spain

| Input variables | Value |

|---|---|

| Trip duration (minutes): | |

| Bicycle | 14.1* |

| Car | 8.4† |

| Distance travelled per trip (km): | |

| Bicycle | 3.29* |

| Car | 3.29† |

| Average speed (km/h): | |

| Bicycle | 14† |

| Car | 23.5‡ |

| Fatal road traffic incident rate in Barcelona (deaths/billion km travelled): | |

| Bicycle | 4.54§ |

| Car | 3.72§ |

| No of trips per day: | |

| Bicycle | 37 669* |

| Car | 363 863‡ |

| Percentage of vehicles in Barcelona: | |

| Diesel | 44¶ |

| Petrol | 66¶ |

| Efficiency of vehicle fleet in Barcelona (L/100 km): | |

| Diesel | 7¶ |

| Petrol | 9¶ |

| Carbon dioxide emissions (kg/L): | |

| Diesel | 2.61** |

| Petrol | 2.38** |

| Expected mortality in 16-64 age population per year (deaths/1000 inhabitants) | 2.05†† |

| No of trips per person per day | 1.5† |

| Total population of Barcelona (inhabitants) | 1.6 million‡ |

| Population using Bicing each day | 28 251† |

| Population changing from car to bicycle | 25 426† |

*Average values of Bicing system in 2009.

†Assumptions (see web extra for description).

‡Data from Barcelona council 2009.

§Data from Barcelona Public Health Agency, 2002-10.

¶Data from Spanish traffic department, 2008.

**Catalan Office for Climate Change, 2010.

††Catalan Population in 2007.

Cycling and car use

We obtained statistics on travel by car, cycling, and Bicing use in Barcelona from a combination of data provided by the Bicing management company, Barcelona de Serveis Municipals (B:SM) and from travel surveys carried out by the city and by the metropolitan area transportation departments.11 12 Based on these sources of data, we estimated the mean number of trips daily and duration of trip by travel mode in the city. We calculated that 28 251 Bicing members used the scheme regularly. We assumed that 90% of these users (n=25 426) were new cyclists who had shifted travel mode from cars and that their current Bicing trips replaced the same trips previously made by a car—the same number of trips and same distance for each trip. We also carried out sensitivity analyses using different scenarios to assess the impact of shifting from other modes of transport, with 10% changing from cars, 60% from public transport, and 30% from walking, based on figures in a UN report (see web extra table 9).1

Air pollution

For the domain of air pollution we considered exposure to particulate matter less than 2.5 µm, which has shown strong associations with all cause mortality.13 14 15 We assessed the levels of exposure and inhaled dose in car users compared with Bicing users (see web extra appendix figure 4). Concentrations for each mode were obtained from a study carried out in Barcelona.16 We assumed that the relative concentrations between modes were representative of annual average relative concentrations. We estimated yearly inhaled doses of these contaminants, accounting for mode specific inhalation rates, exposures, and duration of trip, as in a previous study.17 To simplify, we assumed non-travel times to be spent resting and sleeping while exposed to background annual concentrations of particulate matter less than 2.5 µm. To estimate the relative risk of mortality associated with incremental intake of pollutant for cyclists compared with car users, similar to another study,9 we applied the ratio between the estimated inhaled dose for cyclists and for car users to exposure-response functions reported in the literature. We used the update by previous researchers,18 of the most commonly used relative risk functions in risk assessment of exposure to particulate matter less than 2.5 µm.19 As a sensitivity analysis, we also carried out this calculation for mortality risks associated with increments of black smoke inhalation (a mix of particles and carbon fume resulting from the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels) and tested the hypothesis that traffic related air pollution may be more toxic than the ambient concentrations found in the cities from which the relative risk functions were derived.13 14

Traffic mortality

For road traffic incidents we used data from the Barcelona public health agency.20 We derived mortality from incidents per billion kilometres travelled by bicycle and by car from estimates of total yearly distance travelled by bicycle and car linked to traffic mortality data by mode in the past nine years. We then calculated relative risks of all cause mortality in a road traffic crash for cyclists compared with car drivers, assuming the same distance travelled for each mode, as in a previous study.9 (See web extra figure 5.)

Physical activity

To quantify the benefits of physical activity, we followed the approach presented in the health economic assessment tool for cycling project.6 This instrument uses relative risks of all cause mortality for commuters who use bicycles compared with other modes of transport derived from a study in Copenhagen of the largest health cohort that specifically considered health effects of commuting by bicycle.21 As in the health economic assessment tool for cycling, we adjusted the relative risk function for daily average distances cycled in Barcelona compared with Copenhagen (see web extra figure 6).

Mortality rates

Using the relevant relative risk functions from our three domains derived for our study conditions in Barcelona, we calculated the change in mortality (increment or decrement) associated with travel by cycling using the Bicing initiative. To obtain the population attributable number of deaths as in other classic risk assessment frameworks, we applied the relative risk to the number of deaths in our population of interest.22 23 To quantify the number of deaths expected in the Bicing population assumed to have started cycling when the initiative was implemented (90% of users in our scenario), we used all cause mortality rates in the population aged between 16 and 64 years (average 39 years) in the Barcelona region (2.05 deaths per 1000 inhabitants per year in 2007), reported by the Statistical Institute of Catalonia.24 We had no information on the specific age distribution of our Bicing population, so we carried out a sensitivity analysis to quantify the effects on mortality related to physical activity for the scenario using a younger age distribution (average 33 years) based on a report on cycling25 and older age distribution (average 48 years) (see web extra table 10 and figures 8-10).

Carbon dioxide emissions

We estimated the savings in carbon dioxide emissions following guidelines and emission factors provided by the Catalan Office of Climate Change.26 These values were calibrated to the Barcelona vehicle fleet (number of vehicles using diesel or petrol, and engine efficiency).27

Statistical analysis

We linked the various model parts in a quantitative model built in Analytica 4.2 (Lumina Decisions Systems, CA, 2010) Monte Carlo simulation program. The main model uses average values for the variable inputs.

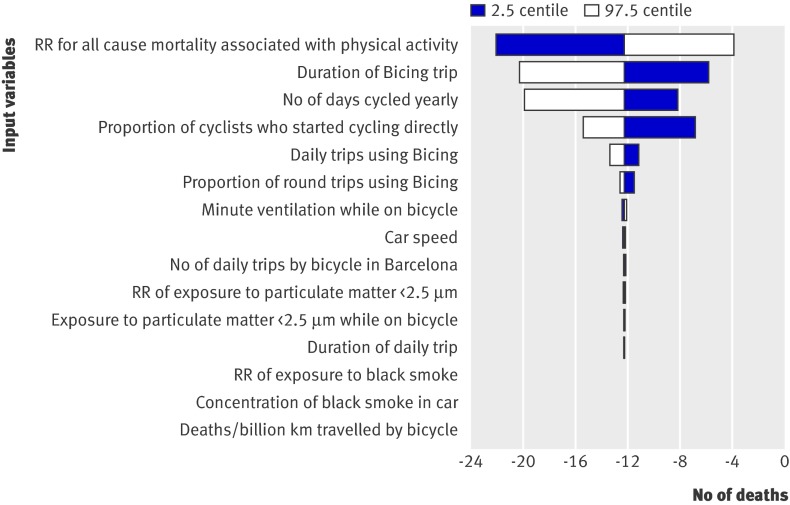

We carried out a sensitivity analysis to test the effect of using alternative values for 15 of the variable inputs. These variables were either used to construct other variables or used directly in the analysis. The sensitivity analysis was meant to assess the stability of our results when using a range of possible input values, provide a range of likely outcomes as a simple form of uncertainty and variability analysis, and identify which inputs are most influential in determining the outcomes. The range of values included for each tested variable depended on the type of information available on the probability distribution for each variable (see web extra table 8). When the data were available, we used the mean and standard deviation to create a normal distribution. If data were not available or the source of data did not include information from distribution variables, we used triangular distributions. If it was possible to select a minimum and maximum from the data or to compare the results of different datasets, we chose a triangular distribution with a maximum and minimum based on the data. For input variables without any other information than the mean, we assumed the triangular distribution with minimum and maximum values to be 50% around the mean value. This uncertainty range was chosen to avoid underestimation of the uncertainty. We identified input variables of highest importance by calculating rank order correlations between each variable and the model outcome. A tornado plot illustrated the effect of uncertainty, which shows the effect on the overall results in the model of varying each input variable individually.

Results

The estimated relative risk for all cause mortality associated with physical activity among the residents of Barcelona who travelled by bicycle (Bicing initiative) compared with by car was 0.80, resulting in an attributable fraction of 0.23 avoided deaths in the Bicing population who had shifted mode of transport from the car. An estimated 12.46 deaths were avoided each year. The relative risk of all cause mortality related to the incremental inhalation of particulate matter less than 2.5 µm was 1.002. The corresponding mortality attributable fraction was 0.002, leading to an estimated 0.13 expected annual number of deaths from air pollution in the Bicing population. The relative risk of road traffic crashes for the Bicing population compared with car users was 1.0007, with an associated attributable fraction of 0.0007, resulting in 0.03 extra deaths per year from road traffic incidents in the Bicing population. As a result, 52.15 deaths would have been expected each year, but because cycling was used as a typical means of transport, the number of annual deaths was reduced by 12.28 to 39.87 (table 2).

Table 2.

Main results from health impact assessment of Bicing initiative in Barcelona

| Variables | Relative risk* | AFexp† | Deaths/year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Road traffic injury | 1.0007 | 0.0007 | 0.03 |

| Air pollution (particulate matter <2.5 µm) | 1.002 | 0.002 | 0.13 |

| Physical activity | 0.80 | −0.23 | −12.46 |

| Carbon dioxide emissions saved (kg/year)‡ | — | — | 9 062 344 |

*Relative risk of death during cycling compared with travel by car.

†Attributable fraction of mortality among exposed (Bicing users).

‡Calculated for Barcelona vehicle fleet, reported in 2008 by Spanish traffic department.

The results were most sensitive to the variations imposed on the relative risk associated with physical activity and mortality, derived from a previous study,21 the average duration of the trip by bicycle, the number of days travelled by bicycle per year per person in Barcelona, and the proportion of cyclists who started cycling when Bicing was implemented. These four variables, in that order, had the highest correlation with the combined mortality and led to the greatest variations in net number of deaths per year in the new cyclist population (see figure and web extra figure 7). Using black smoke instead of particulate matter less than 2.5 µm as a proxy for air pollution slightly reduced the negative effects of cycling (0.04 v 0.13 deaths/year) (see web extra table 4) despite the greater contrasts between exposures during cycling and travel by car, because of the lower relative risk reported in the limited literature on black smoke. Applying a factor of 5 to account for the assumed higher toxicity of traffic related exposure to particulate matter less than 2.5 µm14 increased all cause mortality to 0.52 people each year (see web extra table 5). When the effects of varying the input variables within the ranges specified in the web appendix were analysed, the effect on all cause mortality ranged between 4 and 22 deaths avoided.

Sensitivity analysis tornado plot. Centiles for relative risk (RR) for all cause mortality associated with physical activity refer to arithmetic increase of confidence intervals

As the results were shown to be most sensitive to variations in the relative risk from the physical activity benefits of cycling, the levels of cycling activity were converted to hours of metabolic equivalent tasks a week and the relative risk functions applied from general physical activity (not specifically cycling) reported in a meta-analysis.28 This analysis showed similar benefits among the current population (−12.46 v −11.65 deaths). Additional sensitivity analyses were based on age and shift of travel mode scenarios, considering only physical activity, the main driver of the results. Assuming a younger age population distribution of Bicing users (average 33 years) an estimated 7.43 annual deaths would be avoided instead of the 12.46 from the baseline analyses, whereas assuming a higher age distribution (mean 48 years) an estimated 20.55 annual deaths would be avoided (see web extra table 10 and figures 8-10). Data on shifts in mode of travel as a result of the Bicing initiative could not be found, but using an alternative scenario with 60% of Bicing users having shifted from public transport, 30% from walking, and 10% from car, had little effect on the number of deaths avoided (10.46 v 12.46) (see web extra table 9).

The annual reduction in carbon dioxide emissions resulting from implementation of the Bicing initiative in Barcelona was estimated to be 9062 metric tonnes (see table 2).

Discussion

The health benefits of physical activity from cycling using the bicycle sharing scheme (Bicing) in Barcelona, Spain, were large compared with the risks from inhalation of air pollutants and road traffic incidents (benefit:risk ratio 77). Also, the potential reduction in carbon dioxide emissions from cycling instead of travel by car represented 0.9% of emissions from all types of motor vehicles in Barcelona in 2009.

Comparison with other studies

Our results corroborate the findings of the two other published assessments of multiple risks and benefits of active transportation. One study found that the health benefits of cycling would be larger (3-14 months gained) than the risks of road traffic incidents (5-9 days lost) and exposure to air pollutants (0.8-40 days lost) if car journeys were substituted by cycling trips.9 The other study found that if urban trips in private motor vehicles were replaced by active travel this would result not only in important health gains but also in reductions in carbon dioxide emissions.10 We built on previous studies6 9 10 by linking a specific and newly introduced policy in a real life setting to the effects on health. The preceding studies considered the impacts of hypothetical changes in choice of travel mode not associated with an implemented policy or programme and modelled populations much larger than in our study, generating perhaps unrealistic estimates compared with integrating observed usage numbers as in our study.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Along with our efforts to assess the effects of an implemented policy, we incorporated data and measurements relevant to the local context, such as air pollution concentrations, measured previously in different transportation microenvironments in Barcelona. Grounding this work in a real life setting with observed measurements presents an important strength of the study design. We chose all cause mortality as our main outcome to provide the most robust results possible, given the strongest evidence found in the epidemiological literature for that outcome.

As in all risk assessments, our study was limited by the availability of data and the necessity to make assumptions to model likely scenarios. We carried out sensitivity analyses to assess the stability of our results and tested effects of deviations from our main assumptions and data choices. Included in the sensitivity analysis were, for example, relative risk functions from the literature, choice and toxicity of pollutants, age distribution, shift in mode of travel, and environmental and travel conditions in Barcelona. Importantly, we found that in all the scenarios we tested a net benefit was always evident for Bicing users.

Not all assumptions and data inputs, however, could be tested in the sensitivity analysis, as some remain difficult to quantify owing to lack of knowledge in the research area or the added complexity for modelling, going beyond the scope of this first pass assessment. For example, the benefits of physical activity may be a function of baseline levels of physical activity and health status, although the shape of dose-response functions for changes in physical activity at different baseline levels is not well established, especially for active travel.21 It is possible that people who had more sedentary lifestyles could have benefited more from the shift to cycling than those who already participate in sports and exercise activities,29 but we did not have this information.

If shifts in mode of travel were generated predominately from walking and public transit, the savings in carbon dioxide emissions would also be lower than our estimations. Hence we could potentially be over-estimating benefits of the Bicing initiative on carbon dioxide emissions in our central calculations of value. However, we did not consider the possible positive effects of the Bicing initiative in encouraging cycling not using Bicing thus triggering a larger number of shifts in mode of travel, nor the potential for cycling trips to replace longer trips in vehicles (there may be a leveraging effect of the cycling policy), which would all lead to estimating greater benefits on emissions. Another factor not accounted for in the analysis is the ability of cyclists to choose less trafficked routes, hence reducing their exposures. In Barcelona, however, bicycle lanes tend to be situated in roads with heavy traffic and these present likely travel routes for cyclists. Anyhow, varying the exposure concentration of particulate matter less than 2.5 µm in the sensitivity analysis had minor effects on overall mortality.

Finally, there are many other benefits and some potential risks associated with cycling that were not integrated in this assessment. We estimated savings in carbon dioxide emissions but did not measure reductions in other emissions or the potential associated health effects or cost savings of reductions in emissions. Based on the small 4% reduction in car journeys in Barcelona according to our calculations on shift in travel mode, it is unlikely that savings on emissions would be sufficient to have a meaningful effect on population exposures and their health implications, especially considering the high uncertainty associated with estimating health impacts of probable unequal distribution of reduction to exposures. Considering possible larger implications of cycling on shifts in mode of travel (for example, a trend phenomenon leading to more cycling in general in the city) and the increase in replacement of car journeys by cycling trips over the years, it may be worth accounting for changes in exposures in the general population in future work. A similar argument can be made about reductions in exposure to road traffic crashes and noise that can accompany a reduction in car use—for example, fewer cars on the road increases traffic safety for the general population. Future assessments may take such effects in the general population into account, along with other exposures or behaviours potentially affected by the active travel policy, such as heat or recreational cycling. Other future improvements in the modelling framework include estimating morbidity, given that mortality represents only a part of the underlying groups of diseases associated with the three main domains. Morbidity also involves greater uncertainty in the calculations but can show larger effects on public health for both risks30 and benefits.31 32 33 Furthermore, analyses of years of life lost or disability adjusted life years are likely to show even more pointedly the benefits of the policy, given the numbers of avoided deaths in relatively young populations. Follow-up of this work should also include a more detailed uncertainty and variability analysis, so that the distribution in the population of exposures and behaviours and different categories of demographics and health status can be accounted for rather than providing only central estimates (albeit with sensitivity analyses).

Conclusion and policy implications

The Bicing initiative is a policy measure that has been highly successful in terms of number of subscribers and led to a large increase in trips on bicycles, which is often hard to achieve.34 A previous study showed that interventions generally led to an average 3% increase in the prevalence of cycling in the population. Bicing so far has increased the number of cycling trips by 30%. Eleven per cent of the population in Barcelona subscribes to Bicing, although based on our estimates only 1.7% of the population are regular users.

We provide the first assessment of multiple risks and benefits of a policy implemented to promote cycling. Our work has shown that low cost public bicycle sharing systems aimed at encouraging commuters to cycle are worth implementing in other cities, not only for the health benefits but also for potential co-benefits such as a reduction in air pollution and greenhouse gases.35 Many cities worldwide have shown an interest in developing bicycle sharing schemes, and this assessment provides useful data in support of such solutions. Future work should refine the assessment and integrate a more comprehensive array of domains and outcomes (including, for example, morbidity), which will provide further indications of how to implement best active travel policies. This initial assessment is, however, important now to encourage cities to follow the lead of Barcelona and other major cities as a cost saving solution for alternative transportation and promotion of health.

What is already known on this topic

Public bicycle sharing schemes are becoming increasingly popular in cities worldwide

These schemes provide a sustainable mode of transport for short urban trips

Active transport policies such as bicycle sharing schemes promote physical activity

What this study adds

The health benefits of physical activity from cycling using the bicycle sharing scheme (Bicing) in Barcelona, Spain, were large compared with the risks from inhalation of air pollutants and road traffic incidents

Public bicycle sharing schemes can help improve public health

Contributors: AdeN and MJN conceived and designed the study. DR-R and AdeN collected the data. All authors analysed and interpreted the data, wrote the manuscript, and edited and approved the final version for submission. AdeN and MJN are guarantors.

Funding: This work is part of the European wide project Transportation Air pollution and Physical ActivitieS: an integrated health risk assessment progamme of climate change and urban policies (TAPAS), which has partners in Barcelona, Basel, Copenhagen, Paris, Prague, and Warsaw. TAPAS is a four year project funded by the Coca-Cola Foundation, AGAUR, and CREAL.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;343:d4521

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Assumptions and calculation steps used to derive model inputs from available data

Conceptual framework for assessment of health impact

References

- 1.Midgley P. Bicycle-sharing schemes: enhancing sustainable mobility in urban areas. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2011.

- 2.World Health Organization. Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. WHO, 2004.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity: halting the epidemic by making health easier. CDC, 2010.

- 4.Commission of the European Communities. Promoting healthy diets and physical activity: a European dimension for the prevention of overweight, obesity and chronic diseases. EU, 2005.

- 5.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC fourth assessment report: climate change. Synthesis report. IPCC, 2007.

- 6.World Health Organization. Health economic assessment tool (HEAT) for cycling. WHO, 2008.

- 7.Lopez A. Bicing, transporte público individual. 2009. Direcció de Serveis de Mobilitat, 2009.

- 8.De Nazelle A, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Anto JM, Brauer M, Briggs D, Braun-Fahrlander C, et al. Improving health through policies that promote active travel: a review of evidence to support integrated health impact assessment. Environ Int 2011;37:766-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johan H, Boogaard H, Nijland H, Hoek G. Do the health benefits of cycling outweigh the risks? Environ Health Perspect 2010;118:1109-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woodcock J, Edwards P, Tonne C, Armstrong BG, Ashiru O, Banister D, et al. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: urban land transport. Lancet 2009;374:1930-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Autoridad del Transporte Metropolitano. EMQ 2006, Región Metropolitana de Barcelona. ATM. 2007.

- 12.Direcció de Serveis de Mobilitat. Dades Bàsiques de Mobilitat 2009. Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2010.

- 13.Laden F, Neas LM, Dockery DW, Schwartz J. Association of fine particulate matter from different sources with daily mortality in six US cities. Environ Health Perspect 2000;108:941-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wichmann H, Spix C, Tuch T, Wölke G, Peters A, Heinrich J, et al. Daily mortality and fine and ultrafine particles in Erfurt, Germany. Health Effects Institute, 2000. [PubMed]

- 15.Pope CA III. Mortality effects of longer term exposures to fine particulate air pollution: review of recent epidemiological evidence. Inhal Toxicol 2007;19(suppl 1):33-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Nazelle A, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Pérez L, Kunzli N, Lobo A. Pilot study of Barcelona commuters’ exposure to particulate matter. Epidemiology 2008;19:S130-1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Nazelle A, Rodriguez DA, Crawford-Brown D. The built environment and health: impacts of pedestrian-friendly designs on air pollution exposure. Sci Total Environ 2009;407:2525-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krewski D, Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Ma R, Hughes E, Shi Y, et al. Extended follow-up and spatial analysis of the American Cancer Society Study linking particulate air pollution and mortality. Health Effects Institute 140, 2009. [PubMed]

- 19.Pope CA III, Burnett RT, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Krewski D, Ito K, et al. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. JAMA 2002;287:1132-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santamariña E, Pérez C. Accidents i lesionats de transit a Barcelona. Agencia de Salut Publica de Barcelona, 2008.

- 21.Andersen LB, Schnohr P, Schroll M, Hein HO. All-cause mortality associated with physical activity during leisure time, work, sports, and cycling to work. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1621-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez L, Kunzli N. From measures of effects to measures of potential impact. Int J Public Health 2009;54:45-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. WHO, 2008.

- 24.Servicio de Información y Estudios. Análisis de la mortalidad en Cataluña, 2007. Generalitat de Catalunya. 2010.

- 25.GESOP. Barómetro anual de la bicicleta. Fundación ECA Bureau Veritas. PTOP, 2009.

- 26.Oficina Catalana del Cambio Climático. Guía práctica para el cálculo de emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero. Generalitat de Catalunya, 2010.

- 27.Dirección General de Tráfico. Parque Nacional Automóvil, distribuido por provincias, tipos y carburantes. DGT, 2008.

- 28.Woodcock J, Franco OH, Orsini N, Roberts I. Non-vigorous physical activity and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:121-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouchard C. Physical activity and health: introduction to the dose-response symposium. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001;33:S347-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aertsens J, de Geus B, Vandenbulcke G, Degraeuwe B, Broekx S, De Nocker L, et al. Commuting by bike in Belgium, the costs of minor accidents. Accid Anal Prev 2010;42:2149-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.CDC. Physical activity and health. A report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, 1996.

- 32.Berlin JA, Colditz GA. A meta-analysis of physical activity in the prevention of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol 1990;132:612-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tuxworth W, Nevill AM, White C, Jenkins C. Health, fitness, physical activity, and morbidity of middle aged male factory workers. I. Br J Ind Med 1986;43:733-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang L, Sahlqvist S, McMinn A, Griffin SJ, Ogilvie D. Interventions to promote cycling: systematic review. BMJ 2010;341:c5293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Nazelle A, Nieuwenhuijsen M. Integrated health impact assessment of cycling. Occup Environ Med 2010;67:76-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Assumptions and calculation steps used to derive model inputs from available data

Conceptual framework for assessment of health impact