Abstract

The computational fluid dynamics methods for the limited flow rate and the small dimensions of an intracranial artery stenosis may help demonstrate the stroke mechanism in intracranial atherosclerosis. We have modeled the high wall shear stress (WSS) in a severe M1 stenosis. The high WSS in the systolic phase of the cardiac cycle was well-correlated with a thick fibrous cap atheroma with enhancement, as was determined using high-resolution plaque imaging techniques in a severe stenosis of the middle cerebral artery.

Keywords: Cerebral artery; Atherosclerosis; MRI, Plaque rupture, Fluid structure interaction

INTRODUCTION

Although intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis is angiographically more common than extracranial lesions in Asians including Koreans, the pattern and mechanism of cerebral infarction in partially occluded atherosclerotic cerebral arteries remain unknown (1, 2). A few studies have been conducted on the hemodynamics in small-caliber intracranial vessels, and especially in vessels associated with severe stenosis (3-8). The dearth of research in this area is in part due to the limited resolution of stenotic lumens as imaged by the current technologies, and this has precluded the development of realistic geometry for use in finite element modeling and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis.

Investigating the subject-specific boundary conditions for intracranial arteries and the development of finite element models from stenotic intracranial arteries using clinically applicable imaging modalities depend on the geometry data for the model, the segmenting images to determine the shape of the lumen and the construction of a computational grid for the fluid domain (9, 10). By using the flowchart tool for patient-specific computational grid reconstruction and blood flow numerical simulations, we developed a selected in vivo imaging technique for high-resolution vessel wall studies in conjunction with medical image-based CFD techniques to elucidate the relationship between the local hemodynamics, as a result of atherosclerosis of the small intracranial arteries, and the patient's symptom presentation.

CASE REPORT

Data transfer and reconstruction of the 3D vessel geometry from the 3D angiography, which was obtained using an AXIOM Artis dBA (Siemens Medical Solution, Erlangen, Germany,) were performed using Mimics V10.2 software. The complex model was discretized into finite elements or volumes to strike a nontrivial balance between the solution accuracy and the computational effort. Three dimensional computational meshes can be readily generated for arbitrarily complex geometries using widely available mesh generation tools such as HyperMesh (Altair Engineering, Inc., Auckland, New Zealand). Computational analysis of the blood flow in the blood vessels was performed using the commercial finite element software ADINA version 8.5 (ADINA R & D, Inc., Lebanon, MA). The number of tetrahedral elements was 300,724 and the number of nodes was 56,448.

Blood flow was assumed to be laminar, viscous, Newtonian and incompressible because of its inherent flow characteristics. No-slip boundary conditions were assumed for the flow viscosity produced between the fluid and the wall surface of the blood vessels. Simulations were performed with the following material constants: the blood density was 1,100 kg/m3 and blood dynamic viscosity was 0.004 Poiseuille. To achieve truly patient-specific modeling, the boundary conditions at the inflow boundary were based on the pulsatile periodic flow rate. The unsteady flows in the internal carotid artery were computed over an interval of 3 cardiac cycles. The results corresponding to the third cycle were considered to be independent of the initial conditions and these were used for flow analysis. The velocity and flow rate of the internal carotid artery were obtained from gated phase contrast angiography (PCA) in an age-matched male who did not have any intracranial vascular disease. The parameters for the gated PCA synchronized to the heart cycle were the fast field echo sequence (FFE), repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE) = 11/69 ms, flip angle = 15°, field of view (FOV) = 150 × 150 mm, matrix size = 340 × 312, sensitivity encoding (SENSE) factor = 3 and the number of excitations (NEX) = 2. We measured the velocity (cm/s) or flow rate (mL/s) using the Quantitative-flow software Viewforum version R 5.1 (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands).

The CFD results were incorporated into the high resolution MRI obtained from the left M1. The MRI scans were performed using a 3 Tesla MRI system (Philips Achieva, Best, The Netherlands) and a head and neck coil. The MRI and MR angiography (MRA) protocol included four different scans: three-dimensional time of flight (TOF)-MRA and the pre- and post-proton-density weighted images (PDWIs). TOF-MRA was obtained in the axial plane and the data was reconstructed using a dedicated online post-processing tool to determine the blood vessel architecture. Both the raw TOF-MRA data and the reconstructed blood vessel data were used for localizing the subsequent PDWIs. The imaging parameters for the TOF-MRA scan were FFE, TR/TE = 25/3.4 ms, flip angle = 20°, FOV = 250 × 250 mm, matrix size = 624 × 320, SENSE factor = 2 and NEX = 1. The TOF-MRA scan time was 2:38. The PD scan parameters were an SE sequence, TR/TE = 1000/20 ms, FOV = 200 × 200 mm, matrix size = 512 × 494, SENSE factor = 2 and NEX = 1. The scan time for each PDWI was 5 minutes 30 seconds. The pre- and post-PDWIs were reconstructed to form oblique-coronal views through the vessel in order to localize the plaque longitudinally along the vessel. The reason we chose PDWI is to reduce the scan time as well as to see the T1 and T2 effects from one scan sequence because high resolution images are vulnerable to the patient's motion during the long scan time.

Our Institutional Review Board approved this study, and we obtained written informed consent from the patient and the patient's family. We enrolled a 45-year-old male patient who presented with right arm weakness and he revealed an acute ischemic change in the perforator and borderzone types on the diffusion-weighted image (Fig. 1A). The man had hypertension, diabetes mellitus and a history of coronary bypass surgery, and he was a smoker and alcohol drinker. He did not have arterial fibrillation or any coagulation disorders.

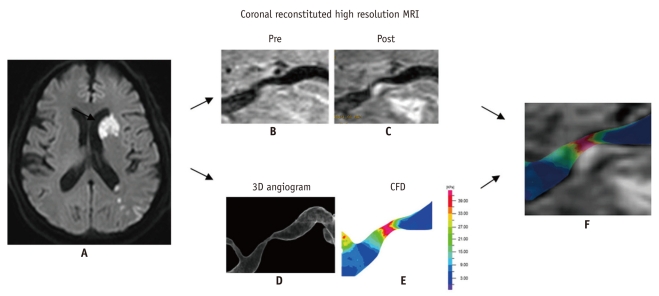

Fig. 1.

Computational fluid dynamics study in severe M1 stenosis with enhanced plaque seen on high resolution MRI.

Diffusion-weighted image (A) shows perforator and borderzone infarcts (arrow) in 55-year-old male who presented with right hemiparesis and aphasia. Coronal reconstituted pre- (B) and post- (C) Gadolinium enhanced high resolution MR images shows eccentric plaque with enhancement of thick fibrous cap atheroma, which may explain mechanism of stroke as having arisen from surface erosion for borderzone infarcts and plaque encroachment for perforator infarct. CFD obtained from 3D angiography (D) reveals increased wall shear stress (E). Distribution of wall shear stress showed that highest wall shear stress was present during systolic phase (not shown). Fusion image (F) reveals markedly increased wall shear stress at upstream side of enhancing plaque, as determined by CFD. CFD = computational fluid dynamics.

A smooth surface enhanced plaque was evident in the coronal reconstructed images (Fig. 1B, C) in the anteroinferior portion of the left M1, as shown on the sagittal high-resolution 3D MRI. The 3D cerebral angiogram (Fig. 1D) yielded the wall shear stress (WSS) map (Fig. 1E). The distribution of WSS across the average systolic and diastolic blood pressures permitted construction of a contour map of the velocity in each cardiac cycle (Fig. 1E). The average velocities at the carotid bifurcation in the systolic and diastolic phases were 0.73 m/s and 0.52 m/s, respectively. The WSS obtained during the three phases of a cardiac cycle revealed that the highest WSS was present during the peak systolic phase. A combination of the WSS map and the MRI coronal reconstituted image indicated that the highest WSS corresponded to the most severe stenotic segment that included the enhancing plaque (Fig. 1F). The maximum WSSs of the stenotic portion of the vessel during the systolic and diastolic phases were 64 and 31.9 Pa, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The combined use of coronal reconstituted high-resolution MRI and CFD could be helpful to explore the pathophysiology of cerebral infarction in acute stroke patients with severe middle cerebral artery stenosis. We demonstrated that CFD analysis of a small-caliber intracranial artery was feasible and this could be correlated with the atherosclerotic plaque in the stenotic segment, as was determined by high-resolution MRI. The plaque shown on the sagittal high-resolution MRI was clearly distinguished in the coronal reconstituted image and this was characterized by enhancement of the plaque's smooth surface. Thus, the mechanism of stroke in the patient studied here with severe M1 stenosis may have been related to erosion of the thick fibrous plaque cap atheroma as well as plaque encroachment on the perforator, rather than being related to plaque rupture. The borderzone infarct in our patient may have corresponded to thromboembolism that developed at the plaque surface under the influence of hypoperfusion. Therefore, plaque rupture related to an unstable plaque, as in the carotid bulb plaque, was not a possible stroke mechanism in our study patient (3, 11).

Our study revealed that the most severe stenotic segment related to the fibrotic enhancement of a plaque in the stenotic intracranial artery showed high WSS in the systolic phase of the cardiac cycle. Although the high WSS was related to the symptom presentation and it corresponded to a carotid plaque study in which the site of rupture was most probably in the WSS region, erosion of the thick fibrous cap of the enhancing plaque was the most possible mechanism of stroke, which differed from the rupture of the carotid plaque in the highest WSS region. This finding was associated with CFD and this may further elucidate the different pathophysiological mechanisms involved in the stenosis of the extracranial carotid and intracranial arteries.

The sagittal high-resolution MRIs revealed that the most common plaque location was in the anteroinferior direction in our patient (12, 13). However, the sagittal images were limited in their ability to evaluate the entire plaque morphology in the longitudinal arterial lumen. The coronal reconstituted high resolution MRI images generated in our study had the advantages of showing the enhanced fibrotic plaque in the most stenotic segment. Thus, it was possible to correlate the high-resolution MRI with the WSS image.

Our study has several limitations. First, the exact localization of the CFD data compared to the high resolution MRI cannot be exactly matched because the coronal reconstituted image is generated obliquely according to the plaque location. Second, image transfer from the 3D angiogram to the ADINA software required multiple steps and repeated time-consuming processes because such image transfer cannot always be smoothly performed at the present time. If the 3D angiogram is directly transferred to CFD analysis software such as ADINA, then the CFD analysis will be more readily applicable. Last, development of a stenotic model for CFD analysis is difficult and limited when compared to the aneurysm model because the lumen dimension in the stenotic segment can be lost during CFD data generation due to the limited image resolution in the stenotic segment.

Footnotes

This study was supported by a grant (A080201) from the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Suh DC, Lee SH, Kim KR, Park ST, Lim SM, Kim SJ, et al. Pattern of atherosclerotic carotid stenosis in Korean patients with stroke: different involvement of intracranial versus extracranial vessels. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:239–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suh DC, Kim JK, Choi JW, Choi BS, Pyun HW, Choi YJ, et al. Intracranial stenting of severe symptomatic intracranial stenosis: results of 100 consecutive patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:781–785. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groen HC, Gijsen FJ, van der Lugt A, Ferguson MS, Hatsukami TS, van der Steen AF, et al. Plaque rupture in the carotid artery is localized at the high shear stress region: a case report. Stroke. 2007;38:2379–2381. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.484766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groen HC, Gijsen FJ, van der Lugt A, Ferguson MS, Hatsukami TS, Yuan C, et al. High shear stress influences plaque vulnerability Part of the data presented in this paper were published in Stroke 2007;38:2379-81. Neth Heart J. 2008;16:280–283. doi: 10.1007/BF03086163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malek AM, Alper SL, Izumo S. Hemodynamic shear stress and its role in atherosclerosis. JAMA. 1999;282:2035–2042. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.21.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suh DC, Sung KB, Cho YS, Choi CG, Lee HK, Lee JH, et al. Transluminal angioplasty for middle cerebral artery stenosis in patients with acute ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:553–558. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi JW, Kim JK, Choi BS, Kim JH, Hwang HJ, Kim JS, et al. Adjuvant revascularization of intracranial artery occlusion with angioplasty and/or stenting. Neuroradiology. 2009;51:33–43. doi: 10.1007/s00234-008-0462-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi JW, Kim JK, Choi BS, Lim HK, Kim SJ, Kim JS, et al. Angiographic pattern of symptomatic severe M1 stenosis: comparison with presenting symptoms, infarct patterns, perfusion status, and outcome after recanalization. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;29:297–303. doi: 10.1159/000275508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antiga L, Piccinelli M, Botti L, Ene-Iordache B, Remuzzi A, Steinman DA. An image-based modeling framework for patient-specific computational hemodynamics. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2008;46:1097–1112. doi: 10.1007/s11517-008-0420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh TS, Ko YB, Park ST, Yoon K, Lee SW, Park JW, et al. Computational flow dynamics study in severe carotid bulb stenosis with ulceration. Neurointervention. 2010;5:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babikian VL, Caplan LR. Brain embolism is a dynamic process with variable characteristics. Neurology. 2000;54:797–801. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryu CW, Jahng GH, Kim EJ, Choi WS, Yang DM. High resolution wall and lumen MRI of the middle cerebral arteries at 3 tesla. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27:433–442. doi: 10.1159/000209238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niizuma K, Shimizu H, Takada S, Tominaga T. Middle cerebral artery plaque imaging using 3-Tesla high-resolution MRI. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:1137–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]