Abstract

Described herein is the design and synthesis of a discrete heterobifunctional PEG-based pyridyl disulfide/amine-containing linker that can be used in the Cu-free click preparation of bioconjugates. The title PEG-based pyridyl disulfide amine linker is a potentially useful reagent for preparing water-soluble disulfide-linked cargos. It may be particularly valuable in expanding the field of Cu-free click-based bioconjugations to include reductively labile antibody, polymer, or nanoparticle-based drug conjugates.

Keywords: bioconjugation, cleavable linker, Cu-free click reaction, pyridyl disulfide

In order to develop proteins that merge properties of antibodies with biologically active small molecules,1,2 we have recently begun modifying selenocysteine (Sec) antibody constructs (Fc-Sec) by introducing click-compatible functionality.3 This potentially allows the click-attachment of cytotoxic drugs, dyes or other cargo to the Fc portion. Clickable antibody conjugates may require biologically-cleavable linkers that allow release of cargo once delivery to the target has been achieved. However, traditional Huisgen azide-alkyne cycloaddition click reactions employing Cu-catalysis can be incompatible with sensitive protein functionality, and this is one reason why Cu-free click chemistries are gaining greater prevalence.4 Accordingly, versatile hetero-bifunctional linkers are needed that are both compatible with multiple types of Cu-free click reagents and incorporate biologically cleavable bonds.

One approach to introducing a point of bio-cleavage between cargo and carrier is the inclusion of a disulfide bond within the linking component.5–11 Disulfides are synthetically straight-forward to manipulate, and although they are stable under a variety of conditions, they can be efficiently cleaved by reducing agents. Disulfides exhibit good stability in the circulation due to the low reducing potential of blood. In contrast, intracellular concentrations of reducing agents, such as glutathione, are typically 1000-fold greater than in the blood,12 with the reductive potential within cancer cells being even higher.13,14 For these reasons, disulfide-containing constructs can afford effective vehicles for delivery to the cellular targets, and subsequent reductive release of cargo.

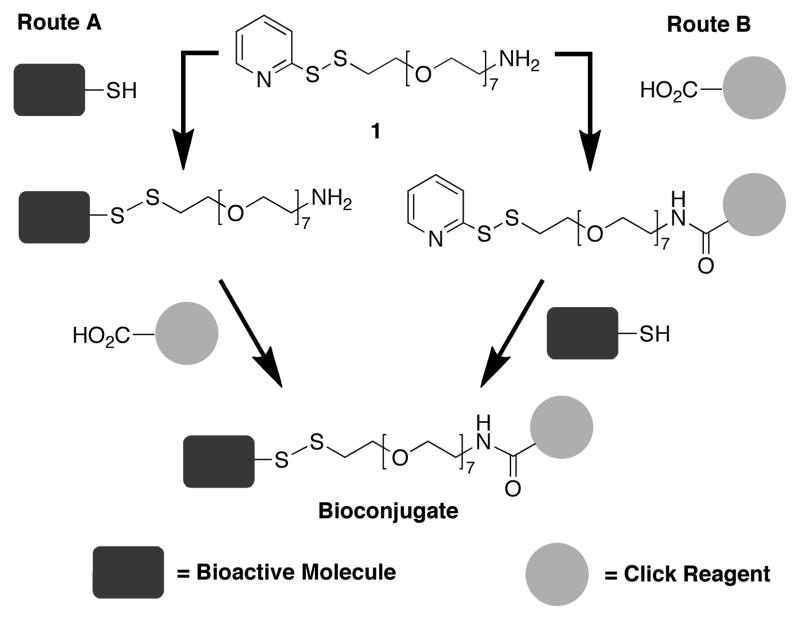

Currently available Cu-free click reagents commonly exhibit considerable hydrophobic character.4 Since cytotoxic drugs also tend to be highly hydrophobic, overcoming poor water solubility can be an important consideration in designing a Cu-free clickable linker for use in Fc-Sec conjugates. The commercially available 2-(pyridyldithio)-ethylamine (PDA)15 is a reagent used for the introduction of short disulfide-containing linkages. Unfortunately, conjugates based on a PDA linker could potentially exhibit unacceptably low solubility in aqueous media. Alternatively, polyethylene glycol (PEG) is a highly water-soluble construct that is used in a range of hetero-bifunctional linkers. However, none of the commercially available PEG-based reagents contain the combination of an activated disulfide (e.g., pyridyl disulfide) together with amine functionality that we desired in our current work. Additionally, previously reported PEG-based pyridyl disulfide/amine-containing linkers have been prepared by polymerization reactions that yield heterogenous reactions products.16 Herein we describe the design and synthesis of a discrete heterobifunctional PEG-based pyridyl disulfide/amine-containing linker (1) that can be used in the Cu-free click preparation of bioconjugates either by initial coupling of a bioactive molecule through disulfide formation (Route A, Scheme 1) or by initial introduction of the click reagent by amide bond formation (Route B, Scheme 1). (Insert Scheme 1)

Scheme 1.

Structure of PEG pyridiyl disulfide amine linker 1 and its use in the construction of bioconjugates by two routes.

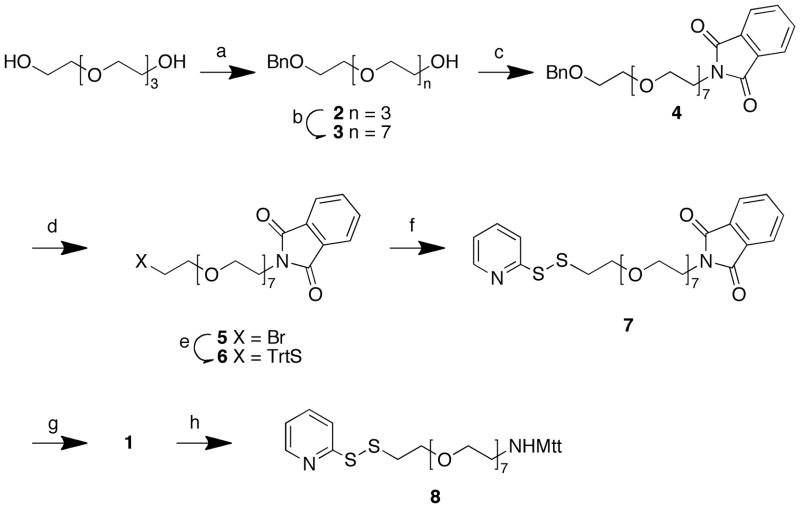

Discrete, highly pure PEG linkers that range in length from 817 to 4818 ethylene glycol units can be prepared from tetraethylene glycol precursors. Our route to 1 began by the monobenzylation of tetraethylene glycol (Scheme 2). Subsequent tosylation of 2 and chain elongation with excess tetraethylene glycol gave 3 in modest yield. Conversion of the primary alcohol to the mesylate and reaction with potassium phthalimide provided the protected amine 4, which was debenzylated, brominated, and then reacted with triphenylmethanethiol to yield the doubly protected amino thiol 6. An activated disulfide was introduced in two steps by removing the S-trityl group in 6 and then reacting the free thiol with pyridylsulfenyl chloride to afford 7 (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Reagents and Conditions: a) BnBr, NaH, THF (74%); b) TsCl, Et3N, DMAP, CH2Cl2 (93%); c) (i) MsCl, Et3N, CH2Cl2; (ii) pottassium phthalimide, DMF (60% over two steps); d) (i) Pd • C, H2, EtOH (78%); (ii) Ph3P, CBr4, CH2Cl2 (70%); e) TrtSH, NaH, DMF (88%); f) (i) TFA/CH2Cl2/(i-Pr)3SH; (ii) 2-mercaptopyridine, SOCl2, CH2Cl2, (51% over two steps); g) NH2NH2, (71%); h) MttCl, DIEA, DMF (40%).

Given the tendency of unsymmetrical disulfides to undergo base and temperature-induced degradation,19 cleavage of the phthalimide group in 7 to yield the free amine 1 could be problematic with commonly used conditions (hydrazine in refluxing ethanol).20 However, the stability of a 2-pyridyldithio-based amino protecting group under piperidine-mediated Fmoc-deblock conditions,21 indicated that the 2-pyridyl group in 7 could potentially stabilize the disulfide bond during treatment with hydrazine. None-the-less, our initial efforts to remove the phthalimide group in 7 using standard hydrazine conditions gave significant disulfide disproportionation (as determined by ESI-MS) that resulted in a relatively low yield of the desired product 1 (48%). However, performing the reaction at ambient temperature decreased side reactions and resulted in an improved yield (71%). To assure stability during storage, the free amine group in 1 was protected with the acid-labile 4-methyltrityl (Mtt) group (compound 8 Scheme 2). The mild conditions required to remove the Mtt group make it compatible with a broad range of disulfide-linked cargo.

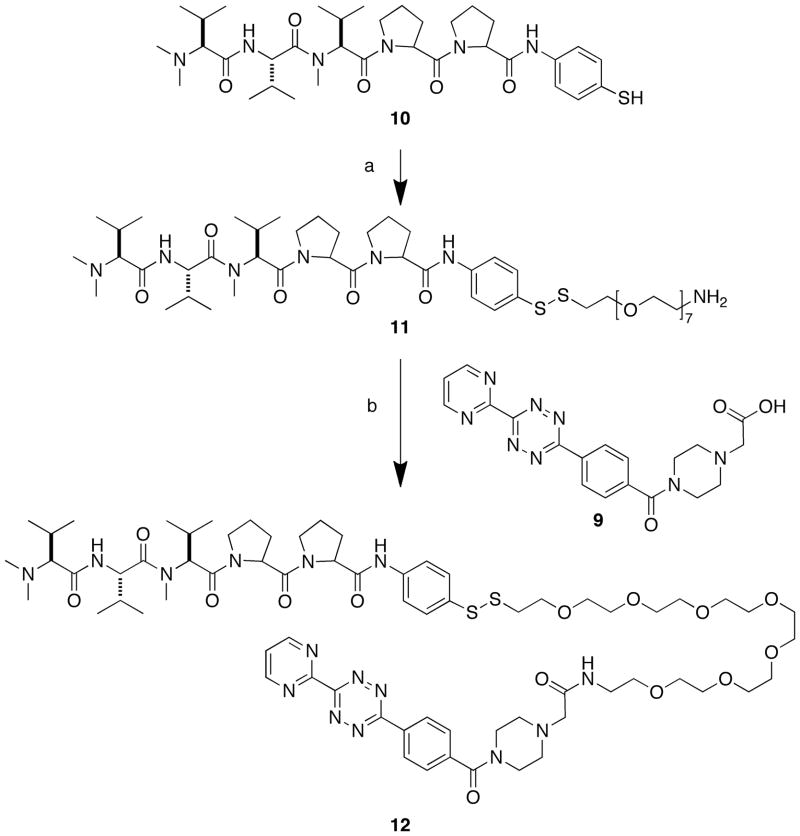

To demonstrate the utility of 8, a cytotoxic derivative of cemadotin22 was appended to one end of the linker via a disulfide bond, and a tetrazine construct (9)23 was introduced to the other end. The tetrazine serves as a diene that undergoes irreversible Cu-free click reactions through very efficient [2+4] inverse-electron-demand Diels-Alder cycloadditions with strained alkenes.4 In order to avoid potential side reactions with free thiols,24 9 was introduced following disulfide exchange with the thiol-containing bioactive cemadotin analog 1025 (Scheme 3). Cemadotin derivatives represent attractive drug cargos for validating the synthetic strategy outlined in Scheme 3, because they contain N-alkylated tripeptide sequences that are prone to acid-catalyzed degradation.26 Disulfide exchange between 8 and 10 and evaporation of solvent gave a crude reaction mixture, which was in modest subjected to Mtt removal (1% TFA in CH2Cl2) to provide 11 yield (Scheme 3). Importantly, no degradation of 10 was observed during under these conditions. Coupling of 11 to 9 (HOAt, diisopropylcarbodiimide and diisopropylethylamine in DMF) gave the fully elaborated construct 12.

Scheme 3.

Reagents and Conditions: a) (i) 8, MeOH (74%); (ii) TFA/CH2Cl2/(i-Pr)3SH (39% for two steps); b) HOAt, DIC, DIEA, DMF (31%).

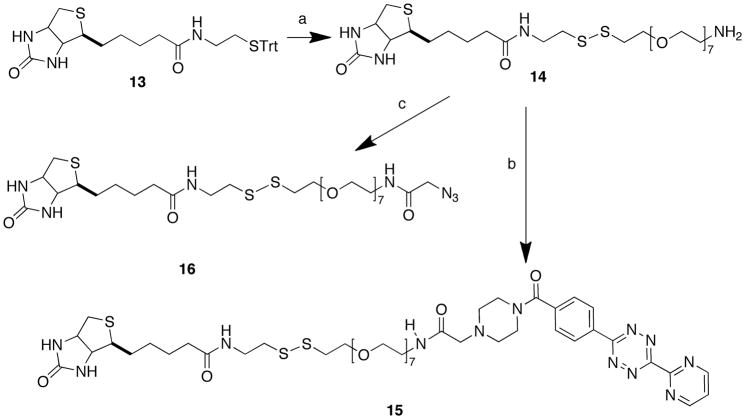

Linker 8 was also used to prepare clickable biotin-containing derivatives 15 and 16 (Scheme 4). Biotin-(STrt)cystamine 13 was converted in three steps to disulfide-containing amine 14 (Scheme 4). HATU-mediated coupling with 9 yielded biotin-containing tetrazine 15, while reaction of 14 with OSu-activated azido acetic acid yielded the corresponding azide 16. Since classical click reactions3 require a reducing agent in order to maintain copper in the +1 oxidation state, disulfides such as 16 are potentially better suited for Cu-free reactions that utilize highly strained cyclooctynes.4

Scheme 4.

Reagents and Conditions: a) (i) TFA/CH2Cl2/(i-Pr)3SH; (ii) 8, MeOH (74%); (iii) TFA/CH2Cl2/(i-Pr)3SH; b) 9, HOAt, DIEA, DMSO (15% overall from 13); c) 1-[(azidoacetyl)oxy]pyrrolidine-2,5-dione, MeCN/H2O (6% overall from 13).

In conclusion, we have shown that the PEG-based pyridyl disulfide amine linker 1 is a useful reagent for preparing water-soluble disulfide-linked cargos. It may be particularly valuable in expanding the field of Cu-free click-based bioconjugations, where applications have traditionally been related to imaging agents. Reagents such as 1 may extend the use of Cu-free click reagents to include reductively labile antibody, polymer, or nanoparticle-based drug conjugates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, Center for Cancer Research, NCI-Frederick and the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Supplementary data (experimental procedures and spectroscopic data for all new compounds) can be found in the online version at doi:

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Hofer T, Thomas JD, Burke TR, Jr, Rader C. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800800105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofer T, Skeffington LR, Chapman CM, Rader C. Biochemistry. 2009;48:12047. doi: 10.1021/bi901744t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angewandte Chem Int Ed Engl. 2001;40:2004. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jewett JC, Bertozzi CR. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:1272. doi: 10.1039/b901970g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito G, Swanson JA, Lee KD. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55:199. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ojima I. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:108. doi: 10.1021/ar700093f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter PJ, Senter PD. Cancer J. 2008;14:154. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318172d704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Low PS, Kularatne SA. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:256. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Vlies AJ, O’Neil CP, Hasegawa U, Hammond N, Hubbell JA. Bioconjug Chem. 2010;21:653. doi: 10.1021/bc9004443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leamon CP, Low PS. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu L, Mahato RI. Bioconjug Chem. 2010;21:2119. doi: 10.1021/bc100346n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meister A, Anderson ME. Annu Rev Biochem. 1983;52:711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howie AF, Forrester LM, Glancey MJ, Schlager JJ, Powis G, Beckett GJ, Hayes JD, Wolf CR. Carcinogenesis. 1990;11:451. doi: 10.1093/carcin/11.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balendiran GK, Dabur R, Fraser D. Cell Biochem Funct. 2004;22:343. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zugates GT, Anderson DG, Little SR, Lawhorn IEB, Langer R. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12726. doi: 10.1021/ja061570n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breitenkamp K, Sill, Kevin N, Skaff H. Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) 2007/127473 A2. Organization, publication WO. 2007 November 8;

- 17.Pilkington-Miksa MA, Sarkar S, Writer MJ, Barker SE, Shamlou PA, Hart SL, Hailes HC, Tabor AB. Eur J Org Chem. 2008:2900. doi: 10.1021/bc0700943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.French AC, Thompson AL, Davis BG. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:1248. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Field L, Parsons TF, Pearson DE. J Org Chem. 1966;31:3550. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wuts PGM, Greene TW. Greene’s Protective Groups in Organic Synthesis. 4. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lapeyre M, Leprince JMM, Oulyadi H, Renard PY, Romieu A, Turcatti G, Vaudry H. Chem Eur J. 2006;12:3655. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Arruda M, Cocchiaro CA, Nelson CM, Grinnell CM, Janssen B, Haupt A, Barlozzari T. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3085–3092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pipkorn R, Waldeck W, Didinger B, Koch M, Mueller G, Wiessler M, Braun K. J Peptide Sci. 2009;15:235. doi: 10.1002/psc.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blackman ML, Royzen M, Fox JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:13518. doi: 10.1021/ja8053805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas Joshua D, Rader C, Burke TR., Jr Unpublished results. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anteunis MJO, van der Auwera C. Int J Peptide Protein Res. 1988;31:301. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.