Abstract

Reperfusion is the key strategy in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) care, and it is time-dependent. Shortening the time from symptom to reperfusion and choosing the optimal reperfusion strategy for STEMI patients are great challenges in practice. We need to improve upon the problems of low reperfusion rate, non-standardized treatment, and economic burden in STEMI care. This article briefly reviews the current status of reperfusion strategy in STEMI care, and also introduces what we will do to bridge the gap between the guidelines and implementation in the clinical setting through the upcoming China STEMI early reperfusion program.

Keywords: Acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), Reperfusion, Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), Fibrinolysis

1. Introduction

Acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), due to sudden coronary artery occlusion, is one of the most life-threatening diseases in the world. Although extensive efforts have been taken to greatly minimize mortality and benefit STEMI patients, a gap between the guidelines and implementation in the clinical setting still exists. This article briefly reviews the current status of reperfusion strategy in STEMI care, and also introduces what we will do to bridge the gap through the upcoming China STEMI early reperfusion program.

2. Reperfusion: a fully proven concept in STEMI care

Reperfusion is a key strategy to decrease mortality and major cardiovascular events in STEMI care. However, the benefit is time-dependent. The infarction-related artery (IRA) must be opened early, consistently, and thoroughly in order to effectively restore myocardial perfusion. The shorter the time from symptom onset to reperfusion, the greater the patient will benefit. According to the guidelines, reperfusion should be performed within 12 h from symptom onset. The current recommendation for door-to-balloon (D2B) time is less than 90 min and that for door-to-needle (D2N) time is less than 30 min (China Society of Cardiology of Chinese Medical Association and Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology, 2010).

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and fibrinolysis are two commonly used reperfusion strategies. Evidences from meta-analysis (Keeley et al., 2003) have confirmed that primary PCI is superior to fibrinolysis in reducing mortality and major cardiovascular events such as nonfatal myocardial infarction, recurrent ischemia and stroke. However, the two techniques differ in their clinical implementation. Primary PCI though a state-of-the-art technique is too complicated to apply in practice. Fibrinolysis, though limited in its effectiveness and posing a risk of bleeding, can be administered quickly and performed relatively easily.

3. Re-evaluation of the pharmacoinvasive strategy in STEMI care

Time is a crucial factor in STEMI care. “Time is myocardium and time is life” is a familiar adage. A delay in undergoing primary PCI greatly reduces the benefits from the procedure. In theory, fibrinolysis can compensate for PCI-related delay. Thus, fibrinolytic therapy combined with mechanical treatment could theoretically improve early thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow and improve clinical outcomes.

However, results from the assessment of the safety and efficacy of a new treatment strategy with percutaneous coronary intervention (ASSENT-4 PCI) trial (ASSENT-4 PCI Investigators, 2006) and the facilitated intervention with enhanced reperfusion speed to stop events (FINESSE) trial (Ellis et al., 2008) were very discouraging. The ASSENT-4 PCI trial showed that facilitated PCI procedure, when compared to primary PCI procedure, increased occurrences of death or stroke in the hospital, the composite endpoint of death, congestive heart failure, and shock, as well as ischemic cardiac complications within 90 d. In the FINESSE trial, the facilitated PCI procedure did not improve the clinical outcomes measured in terms of death or composite endpoint within 90 d, but increased non-intracranial TIMI bleeding events through discharge or on Day 7.

The hypothesis of pharmacoinvasive strategy is supported by recent meta-analysis (D′Souza et al., 2011) when comparing the combined therapy with the standard ischemia-guided PCI. Compared to routine treatment after fibrinolysis, early PCI within 24 h of fibrinolysis significantly reduced the composite endpoint of death, re-infarction and ischemia within 30 d. In addition, no more severe bleeding events, which may result from the extended time interval between PCI and fibrinolysis, were observed.

Thus, 2010 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization (Wijns et al., 2010) recommended that patients going to a non PCI-capable hospital should receive fibrinolysis immediately and then be transferred to a PCI-capable hospital if the expected D2B time is more than 2 h. Routine angiography and urgent PCI are indicated after successful fibrinolysis in a time window of 3–24 h. Rescue PCI should be considered as soon as possible in patients with failed fibrinolysis.

4. Plight of reperfusion: what happens in the real world?

The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) enrolled acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients in North and South America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand to determine the trends in reperfusion therapy between 1999 and 2006 (Eagle et al., 2008). Primary PCI ratio increased from 15% to 44% and fibrinolysis ratio decreased from 41% to 16%. In addition, only 67% of STEMI patients received reperfusion therapy in 2006. The ratio of D2N time <30 min in patients receiving fibrinolysis was 48%, and the ratio of D2B time <90 min in patients undergoing primary PCI was 58%. The situation with STEMI reperfusion therapy in 30 European countries, mostly from 2007 to 2008, was reported recently (Widimsky et al., 2010). Reperfusion therapy was used in 37% to 93% of STEMI patients, varying from country to country. Primary PCI strategy was used in 5% to 92% of STEMI patients, and fibrinolysis strategy was used in 0% to 55% of STEMI patients. D2N time was between 30 to 110 min and D2B time was between 60 to 177 min.

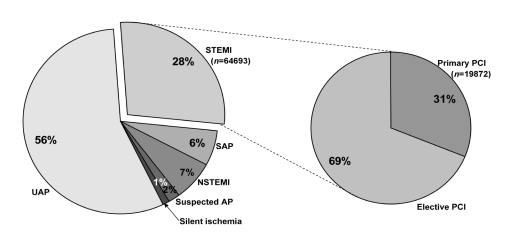

The online PCI registry data of the Ministry of Health (MOH), China showed that 15 221 patients received primary PCI in 2009 (Huo, 2010) and 19 872 patients received primary PCI in 2010 (Fig. 1). Since at least 500 000 individuals are affected with new onset myocardial infarction each year, only about 3% STEMI patients underwent primary PCI in the past two years. Even in larger cities, the result is not promising. Results from a multiple-center registry in Beijing showed that 80.9% STEMI patients received reperfusion therapy (15.4% for fibrinolysis and 65.5% for primary PCI). The median D2B time was 132 min and the median D2N time was 83 min. Only 7% of patients received fibrinolysis and 22% of patients undergoing primary PCI were inside the recommended time window.

Fig. 1.

Numbers of patients receiving PCI procedures in China in 2010

AP: angina pectoris; SAP: stable angina pectoris; UAP: unstable angina pectoris; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; NSTEMI: non ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Several factors may lead to a delay in reperfusion therapy. First, a lack of health awareness in the population prolongs the time of first medical contact (FMC) and the time to obtain procedural consent. Many patients go to emergency department (ED) very late or die before reaching the hospital, because they are not aware that chest pain is a possible sign of STEMI. Even if they arrive at the hospital in time, physicians may need more time to communicate the importance of the reperfusion procedure. Second, the ambulance system may not be able to transfer STEMI patients to a primary PCI-capable hospital immediately. Thus, patients can only get conservative therapy because of fibrinolysis contraindications or outside the therapeutic time window. Third, activation of the cath-lab is often late since departments within the hospital lack adequate coordination or ED physicians do not recognize STEMI in time. Patients may experience delay in the ED waiting for electrocardiogram (ECG) examination, cardiac marker results or waiting for the primary PCI team to arrive. In addition, some patients may refuse primary PCI procedure due to economic issues. In such instances, patients may be more inclined to accept PCI with a bare-metal stent (BMS) since it is a cheaper option when compared to PCI with drug-eluting stent (DES). Other than the less need for repeat target-vessel revascularization (TVR), DES has no clear advantage over BMS in reducing mortality and nonfatal myocardial infarction (Stettler et al., 2007).

5. Efforts to improve STEMI care in China

China STEMI early reperfusion program, set up by MOH of China and organized by both Cardiovascular Physician Branch of Chinese Medical Doctor Association and Society of Cardiology of Chinese Medical Association, will be initiated in July 2011. It aims at building a strong network to improve upon the problems of low reperfusion rate, non-standardized treatment, and economic burden in STEMI care. STEMI patients (including 1 500 patients with BMS implantation) will be enrolled consecutively from 40–60 sites in six months and be followed up for one year. The project will focus on several things: (1) Improving the pre-hospital STEMI care system to allow STEMI patients to go to the right hospital as soon as possible. Patient education and ambulance transfer system efficiency are of prime importance in this section. Methods, such as remote ECG transmission, to activate the cath-lab and guide patients directly to cath-lab, will be encouraged. (2) Establishing an in-hospital STEMI green channel to reach the standards of D2B time <90 min and D2N time <30 min. This will be achieved by setting up a round-the-clock chest pain center and a primary PCI team who will be 24-h on call. (3) Standardizing STEMI reperfusion strategy, and thereby allowing patients to make an informed choice after considering both clinical and economic issues, for example, using more BMS in primary PCI or procedure of fibrinolysis combined with PCI if needed. (4) Promoting secondary prevention of STEMI by setting up a long-term follow-up system, patient education program, and physician training program. (5) Evaluating medical economics to improve the health policy in China.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, shortening the time from symptom to reperfusion and choosing the optimal reperfusion strategy for patients are great challenges in STEMI care. The China STEMI early reperfusion program, when initiated and implemented, will provide better insights and inspire us to move forward in this field.

References

- 1.Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Treatment Strategy with Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (ASSENT-4 PCI) Investigators. Primary versus tenecteplase-facilitated percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (ASSENT-4 PCI): randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;367(9510):569–578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.China Society of Cardiology of Chinese Medical Association, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Chin J Cardiol. 2010;38(8):675–690. (in Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D′Souza SP, Mamas MA, Fraser DG, Fath-Ordoubadi F. Routine early coronary angioplasty versus ischaemia-guided angioplasty after thrombolysis in acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(8):972–982. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eagle KA, Nallamothu BK, Mehta RH, Granger CB, Steg PG, van de Werf F, López-Sendón J, Goodman SG, Quill A, Fox KA. Trends in acute reperfusion therapy for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction from 1999 to 2006: we are getting better but we have got a long way to go. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(5):609–617. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis SG, Tendera M, de Belder MA, van Boven AJ, Widimsky P, Janssens L, Andersen HR, Betriu A, Savonitto S, Adamus J, et al. Facilitated PCI in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(21):2205–2217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huo Y. Current status and development of percutaneous coronary intervention in China. J Zhejiang Univ-Sci B (Biomed & Biotechnol) 2010;11(8):631–633. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1001012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):13–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stettler C, Wandel S, Allemann S, Kastrati A, Morice MC, Schömig A, Pfisterer ME, Stone GW, Leon MB, de Lezo JS, et al. Outcomes associated with drug-eluting and bare-metal stents: a collaborative network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;370(9591):937–948. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Widimsky P, Wijns W, Fajadet J, de Belder M, Knot J, Aaberge L, Andrikopoulos G, Baz JA, Betriu A, Claeys M, et al. Reperfusion therapy for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction in Europe: description of the current situation in 30 countries. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(8):943–957. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wijns W, Kolh P, Danchin N, di Mario C, Falk V, Folliguet T, Garg S, Huber K, James S, Knuuti J, et al. Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: the task force on myocardial revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Eur Heart J. 2010;31(20):2501–2555. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]