Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this analysis was to estimate costs for lung cancer care and evaluate trends in the share of costs that are the responsibility of Medicare beneficiaries.

Methods

SEER-Medicare data from 1991–2003 on n=60,231 lung cancer patients were used to estimate monthly and patient-liability costs for clinical phases of lung cancer care (pre-diagnosis, staging, initial, continuing, and terminal), stratified by treatment, stage, and non- vs. small cell lung cancer. Lung cancer-attributable costs were estimated by subtracting each patient's own pre-diagnosis costs. Costs were estimated as the sum of Medicare reimbursements (payments from Medicare to the service provider), co-insurance reimbursements, and patient-liability costs (deductibles and `co-pays' that are the patient's responsibility). Costs and patient-liability costs were fit with regression models to compare trends by calendar year, adjusting for age at diagnosis.

Results

For a 72-year old diagnosed with lung cancer in 2000, monthly costs in the first 6 months of care ranged from $2,687 (no active treatment) to $9,360 (chemo-radiotherapy), and varied by stage at diagnosis and histologic type. Patient-liability costs represented up to 21.6% of care costs and increased over the period 1992–2003 for most stage and treatment categories, even when care costs decreased or remained unchanged. The greatest monthly patient liability was incurred by chemo-radiotherapy patients ranging across stages from $1,617 to $2,004 per month.

Conclusions

Costs for lung cancer care are substantial and Medicare beneficiaries are responsible for an increasing share of the cost.

Keywords: Lung cancer, Cost Analysis, Medicare, Treatment Costs

Introduction

Accurate estimates of costs are necessary for cost-effectiveness analyses of cancer control interventions, such as mass screening programs or chemoprevention. Detailed estimates of costs are required to project future costs in the event that an intervention or screening program causes a change in incidence, case mix or treatment patterns. Cost analyses are also necessary to evaluate the societal benefit from investments in therapies (1).

Medicare beneficiaries with cancer can face substantial financial burdens. Out-of-pocket spending exceeded 25% percent of annual income for low-income beneficiaries with cancer in 1995 (2) and increased among all beneficiaries between 1997 and 2003 (3, 4). Correlations between increases in out-of-pocket costs and changes in treatment patterns could indicate disparities in care and should be assessed.

Lung cancer is the most common cancer diagnosis in the U.S., with 215,000 new cases in 2008 (5). Lung cancer care accounts for 20% of Medicare's total expenditures for cancer (6). We sought to estimate costs for all phases of lung cancer care (pre-diagnosis, staging, initial treatment, continuing care, and terminal care) for use in a policy model of lung cancer that simulates patient lifetimes in monthly increments. Cost estimates in the literature were incomplete for our purposes for several reasons: categories of phases of care or treatment were collapsed or not reported; costs were those to Medicare or other payers only (i.e., excluding costs paid by beneficiaries); samples were small or non-generalizable (e.g., HMOs); or covered periods before 1991 (6–11). We estimated monthly (as opposed to yearly) costs to be consistent with the policy model and because lung cancer has a median survival of less than a year and twelve-month phases of care could obscure the U-shaped cost pattern typical in cancer (1, 11, 12). Additionally, Yabroff et al. reviewed 60 analyses of cancer treatment costs and found that 50% of them used `unclear' methods (13).

Using SEER-Medicare data, we estimated direct lung cancer care costs from 1992 to 2003. We were interested in how the costs varied by stage at diagnosis, histologic type (non-small cell vs. small cell), treatment, and phase of care (pre-diagnosis, staging, initial, continuing, and terminal). Treatment costs include Medicare reimbursements, co-insurance reimbursements, and costs paid out of pocket by patients, which are not typically included in analyses of Medicare costs.

Methods

SEER-Medicare Data and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

SEER-Medicare data consist of cancer registry files from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program linked to claims data from Medicare, the primary health insurer for 97% of the US population 65 years and older (14). During the time frame used in this longitudinal analysis (1991 through 2003, inclusive), the SEER program collected data from 13 regions representing approximately 14% of the total US population (15). A detailed description of the SEER-Medicare linked database, including its use in compliance with HIPAA regulations, is available at http://healthservices.cancer.gov/seermedicare/.

We included Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 and older who were diagnosed with an AJCC stage I–IV lung cancer between May 1, 1992 and December 31, 2002 and had no previous or subsequent cancer diagnosis. Included individuals were continuously enrolled in both Part A and Part B Medicare coverage from 15 months prior to cancer diagnosis through death or the end of the study period (December 31, 2003). We excluded individuals enrolled in managed care at any time during the study period because health maintenance organizations do not submit detailed claims to Medicare. Patients who received Medicare benefits because of disability or end-stage renal disease were also excluded. Individuals with no claims for an entire phase of cancer care (defined below) were excluded from the analysis of that phase because we assumed they were receiving at a minimum some treatment, supportive care, or monitoring from another component of the health system such as Veterans Affairs. Finally, patients were excluded if the month of diagnosis was unknown, if diagnosis was made at autopsy, or if the date of death recorded in the Medicare database differed from the date of death recorded in the SEER database by greater than 3 months.

Defining Treatments

Treatment groups were defined based on lung cancer treatments received from up to 2 months prior to diagnosis and including 6 months post-diagnosis for individuals diagnosed in AJCC stages I through III. For individuals diagnosed with stage IV cancer, treatment group was assigned based on treatments ever received. Costs are reported for treatment groups with greater than 10% of patients in the type/stage category, except for supportive care only (reported for all categories).

We defined resection as local surgery, wedge resection, pneumonectomy, or lobectomy. Procedures were identified using International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) procedure and Current Procedure Terminology (CPT) codes: local surgery (ICD-9-CM 32.09 and 32.10; CPT 32520), wedge resection (ICD-9-CM 32.29 and 32.30; CPT 32500), pneumonectomy (ICD-9-CM 32.50 and 32.60; CPT 32440, 32442, and 32445), and lobectomy (ICD-9-CM 32.40; CPT 32480, 32482, 32484, and 32486). We additionally included ICD-9-CM codes 32.90, 40.11, and 40.19 and CPT codes 32999 and 38786.

We defined a patient as having received any chemotherapy if there was a hospice, home health, inpatient, outpatient, physician, or durable medical equipment claim with any code for chemotherapy administration (ICD-9-CM procedure 99.25, ICD-9-CM diagnosis V58.1, CPT 96400–96549, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes C1166, C1167, C1178, C9110, C9205, C9207, C9213–C9216, C9411, C9414–C9419, C9420–C9438, G0355, G0356, G0359–G0362, J7150, J8500–J8799, J8999–J9999, Q0083–Q0085, S9325–S9329, S9330–S9379, S9494–S9497 or revenue center codes 0331, 0332, 0335) (14).

We identified patients who received radiation therapy using Medicare claims for radiation treatment planning or administration in any of the Medicare claims files (same files used for chemotherapy) (ICD-9-CM procedures 92.2–-92.29; ICD-9-CM diagnosis V58.0, CPT 77000–77999, 79000–79999, HCPCS S8049, revenue centers 0330, 0333, 0339).

Defining Phases of Care

Costs were assigned to phases of care (Figure 1) that were both clinically identifiable and in increments of one month. For all patients, the pre-diagnosis phase was defined as the 12-month period beginning 15 months prior to diagnosis (where diagnosis was defined as pathological evidence of lung cancer). The three months immediately prior to diagnosis were excluded to avoid including the costs of treating symptoms of an undiagnosed cancer.

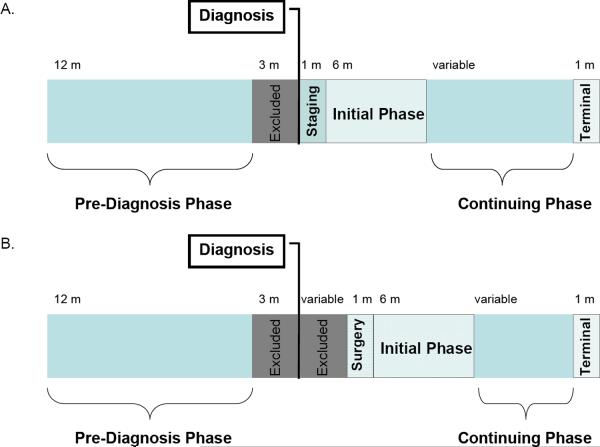

Figure 1.

(A). Phases of care for patients undergoing non-surgical treatments (B) Phases of care for patients undergoing resection. The median time between Diagnosis and Surgery was 18 days; however, for 20% of patients the time between Diagnosis and Surgery was greater than 6 weeks.

For patients not undergoing resection, the month of diagnosis was defined as the staging phase. A month-long staging phase was based on typical clinical practice at our institution. Treatment was divided into 3 phases: initial (6 month period beginning the month after diagnosis and excluding the month before death); continuing (subsequent post-diagnosis period excluding the month of death); and terminal (the month in which death occurred).

For patients undergoing resection, we defined the month of surgery as the 30-days beginning with the date of surgery. Because isolating the cost of surgery from that of post-operative care is necessary to assign costs accurately in simulation models with stochastic mortality events, we defined the initial phase for resection as the 6 month period beginning 30 days post-resection (Figure 1). The monthly staging phase cost as defined for other treatments was impossible to calculate for resection because of heterogeneity in the time required for pre-operative assessment. More than half (53%) of surgical patients received surgery within the month of diagnosis, rendering a monthly staging phase cost immaterial. For the remaining 47% of patients whose surgery occurred in a month after diagnosis, we excluded costs occurring between the month of diagnosis and the date of admission.

The terminal phase was defined as the month of death to permit distinction between phases of care even in patients with limited survival.

Defining Lung Cancer Types and Causes of Death

Patients were grouped into small-cell lung cancers (SCLC) (International Classification of Diseases Oncology 3rd Edition (ICD-O-3) codes 8041, 8042, 8043, 8044) vs. non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC) (ICD-O-3 codes 8010, 8012, 8070, 8071, 8072, 8140, 8481, 8560), since treatment varies by histologic type. SCLC was staged as either limited (AJCC stages I–III) or extensive stage (AJCC stage IV).

Individuals whose death was observed on or before December 31, 2003 were classified by cause of death (lung cancer [excluding operative deaths], ICD-9-CM diagnosis 162.xx; cardiac-related causes, ICD-9-CM 390.xx–398.xx, 402.xx, and 404.xx–429.xx; and all other causes) according to death certificate information in SEER. Death within 30 days of surgical resection for lung cancer was defined as an operative death.

Defining Costs

Costs were estimated as the sum of Medicare reimbursements (payments from Medicare to the service provider), coinsurance reimbursements (payments from a co-insurer to the service provider [in cases in which Medicare is the secondary insurer because the patient is still primarily insured through his or her employer]), and patient-liability costs (deductibles and `co-pays' that are the patient's responsibility but may be paid in part or whole by employer-sponsored supplemental coverage, Medicaid dual-eligibility or through patient-purchased Medigap coverage). The portion of the patient liability that the patient pays out-of-pocket at the time of service (vs. the portion that is paid by Medigap coverage purchased by the patient to reduce point-of-service liabilities) cannot be determined in the SEER-Medicare files.

Payment claims were pulled from six SEER-Medicare files: hospice, home health, Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR, inpatient), Outpatient Standard Analytical File (OUTSAF, outpatient), National Claims History (NCH, physician/supplier), and durable medical equipment (DME). The combination of SEER-Medicare cost components were different for each file (database variable names are listed in parentheses in uppercase). Medicare patients are responsible for a portion of their hospice and home health benefits (a 5% copay for inpatient respite care and a $5 copay per prescription of outpatient drugs for pain/symptom management); however, the SEER-Medicare claims files for hospice and home healthcare do not contain the necessary patient payment variables (personal communication, Sara Durham, Technical Advisor, Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC), February 12, 2010). The payment to the service provider for hospice or home healthcare was therefore the combination of the Medicare claim payment amount (PMT_AMT) and the co-insurer payment amount (PRPAYAMT). Inpatient costs were the sum of the MEDPAR Medicare payment amount (REIMBAMT) plus the MEDPAR total pass through amount (BILTOTPD) [payment by Medicare]; the MEDPAR beneficiary inpatient deductible amount (INPATDED) plus the MEDPAR beneficiary inpatient Part A coinsurance liability amount (COINAMT) plus the MEDPAR beneficiary blood deductible liability amount (BLOODDED) [patient liability]; and the MEDPAR beneficiary primary payer amount (PRIPYAMT) [payment by co-insurer]. Outpatient costs were calculated as the sum of the claim payment amount (PMT_AMT) [payment by Medicare]; the NCH beneficiary Part B coinsurance liability amount (PTB_COIN) plus the NCH beneficiary Part B deductible amount (PTB_DED) plus the NCH beneficiary blood deductible liability amount (BLDDEDAM) [patient liability]; and the NCH primary payer claim paid amount (PRPAYAMT) [payment by co-insurer]. Physician/supplier file costs were the sum of the line payments (which were not available in any of the other Medicare files except for DME): line NCH payment amount (LINEPMT) [payment by Medicare]; the line beneficiary Part B deductible amount (LDEDAMT) plus the line coinsurance amount (COINAMT) [patient liability]; and the line beneficiary primary payer paid amount (LPRPAYAT) [payment by co-insurer]. Durable medical equipment costs were the sum of the line NCH payment amount (LINEPMT) [payment by Medicare]; the line beneficiary Part B deductible amount (LDEDAMT) [patient liability]; and the line beneficiary primary payer paid amount (LPRPAYAT) [payment by co-insurer]. The sum of these payment variables has been validated to represent the reimbursement rates set by CMS on the basis of resource use (unpublished work, personal communication, Faith M. Asper, Technical Advisor, Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC), November 13, 2009).

The cost of operative death for this study was equal to the sum of payments (from Medicare, other payers and the patient) for patients who died within 30 days of resection and included the cost of resection.

Cancer-attributable costs are typically estimated using a case-control approach, drawing controls from the random 5% sample of Medicare enrollees residing in SEER areas (1, 16). We have not taken this approach because lung cancer patients may differ from the general population with respect to health behaviors, particularly related to smoking (17). Thus, to calculate cancer-attributable costs in this study, each patient served as his or her own control: we subtracted each patient's mean monthly pre-diagnosis cost from the monthly costs for the initial and continuing phases of care.

Payments were converted to constant 2006 dollars by adjusting Part A claims using the CMS Prospective Payment System Hospital Price index and Part B claims using the Medicare Economic Index.

Statistical Analysis

To compare trends in treatment costs with trends in patient-liability costs over the time period 1992–2003 while adjusting for changes in patient ages, linear and exponential models for each stage and treatment category were fit with treatment cost and (separately) patient-liability costs as the dependent variable and coefficients for year of diagnosis, age at diagnosis, and an interaction term between age and year. Using significant (α = 0.05) coefficients from linear models, costs were standardized to correspond to a patient diagnosed at age 72 in 2000. When neither age nor year of diagnosis (or the interaction) was significant, costs for a patient diagnosed at age 72 in 2000 is equivalent to the average cost of the entire cohort. Signs of significant terms from the linear model with only significant terms are reported; coefficients are available in Supplemental Results. Exponential models had similar terms but in all cases explained less variability than linear models and are not reported. All data were analyzed using SAS 9.1.3 (Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 60,231 lung cancer patients were included in the sample (Table 1). Most (58.9%) patients were diagnosed between 70 and 80 years of age. Thirteen percent (n= 7,939) of patients lacked either histologic type or stage-at-diagnosis information and were excluded from stratified analyses of treatment category and costs. Most (83%) patients included in the initial phase were diagnosed with NSCLC, with 34.9% of NSCLC patients diagnosed with Stage I or II disease. A substantial portion (16%, n=9,617) of all patients died within two months of diagnosis and were included only in the terminal phase. Death occurred within the window of analysis for 45,777 patients (76% of total), with 81.2 % of deaths attributed to lung cancer and 4.4% of deaths attributed to cardiovascular causes. Few (1.2% of total) patients died of operative causes.

Table 1.

Description of study subjects

| n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Numbers of Patients per Phase* | ||

| Pre-diagnosis | 60,231 | |

| Diagnosis and Staging | 42,675 | |

| Initial | 37,886 | |

| Year of Diagnosis** | ||

| 1992 | 1,883 | 5.0 |

| 1993 | 2,857 | 7.5 |

| 1994 | 2,921 | 7.7 |

| 1995 | 2,948 | 7.8 |

| 1996 | 2,921 | 7.7 |

| 1997 | 2,784 | 7.3 |

| 1998 | 2,851 | 7.5 |

| 1999 | 2,826 | 7.5 |

| 2000 | 5,854 | 15.5 |

| 2001 | 5,051 | 13.3 |

| 2002 | 4,990 | 13.2 |

| Age at diagnosis** | ||

| 65–69 | 7,137 | 18.8 |

| 70–74 | 12,235 | 32.3 |

| 75–79 | 10,096 | 26.6 |

| 80+ | 8,418 | 22.2 |

| Histologic Type and Stage at Diagnosis** | ||

| NSCLC, Stage I and II | 10,987 | 29.0 |

| NSCLC, Stage III | 11,405 | 30.1 |

| NSCLC, Stage IV | 9,117 | 24.1 |

| SCLC, Limited Stage | 3,224 | 8.5 |

| SCLC, Extensive Stage | 3,153 | 8.3 |

| Continuing | 18,933 | |

| Terminal§ | 45,777 | |

| Lung Cancer deaths | 37,170 | 81.2 |

| Cardiac deaths | 2,030 | 4.4 |

| Operative deaths | 565 | 1.2 |

| All other cause deaths | 6,012 | 13.1 |

See Methods and Figure 1 for definitions of phases of care

Limited to the 37,886 patients included in the initial phase analysis

ICD-9 codes 162 (lung cancer); 390-8,402,404–429 (cardiac).

Costs of pre-diagnosis (baseline) and terminal phase care costs

A patient diagnosed with lung cancer at age 72 in 2000 would have incurred an average of $645/month in health care expenditures prior to diagnosis, $107 (16.6%) of which would have been the patient's responsibility (Table 2). Pre-diagnosis health care costs for a 72-year old patient increased by 20% over 10 years, while the costs a typical patient would be responsible for increased 107% over the same period.

Table 2.

Average monthly health care costs during the pre-diagnosis and terminal phases

| Cost, Age | 1992 | 2000 | 2003 | 10-year* % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost, prediagnosis phase | ||||

| 65 | 455.89 | 553.62 | 590.27 | 26.8 |

| 70 | 520.80 | 618.54 | 655.19 | 23.5 |

| 72 | 546.77 | 644.50 | 681.15 | 22.3 |

| 75 | 585.72 | 683.45 | 720.10 | 20.9 |

| 80 | 650.64 | 748.37 | 785.02 | 18.8 |

| Patient-liability, prediagnosis phase | ||||

| 65 | 46.40 | 98.71 | 118.33 | 140.9 |

| 70 | 52.57 | 104.88 | 124.49 | 124.4 |

| 72 | 55.04 | 107.34 | 126.96 | 118.8 |

| 75 | 58.74 | 111.04 | 130.66 | 111.3 |

| 80 | 64.90 | 117.21 | 136.83 | 100.7 |

| Total cost, Lung cancer death | ||||

| 65 | 15,151 | 16,110 | 16,470 | 7.9 |

| 70 | 14,348 | 15,308 | 15,667 | 8.4 |

| 72 | 14,027 | 14,987 | 15,346 | 8.5 |

| 75 | 13,546 | 14,505 | 14,865 | 8.9 |

| 80 | 12,744 | 13,703 | 14,063 | 9.4 |

| Total cost, Cardiac death | ||||

| 65 | 17,652 | 20,665 | 21,794 | 21.3 |

| 70 | 16,587 | 19,599 | 20,729 | 22.7 |

| 72 | 16,160 | 19,173 | 20,302 | 23.3 |

| 75 | 15,521 | 18,533 | 19,663 | 24.3 |

| 80 | 14,455 | 17,467 | 18,597 | 26.0 |

Notes: Costs are estimated for a 72 year old in year 2000 using the linear regression of the form: Monthly Cost = Constant + βAge *(Age in years) + βYear *(Calendar Year – 1992) + βAge*Year *(Age in years)*(Calendar Year – 1992). Terms were included in the final model using a threshold of α = 0.05. Age and calendar year of diagnosis were significant (p<0.0001) predictors of both prediagnosis total costs and patient-liability; the interaction term was not significant and so was excluded from the final models. Regression coefficients are presented in Supplementary Table 2A. Total Cost is the sum of average monthly costs from all sources regardless of payer [Total Cost = Cancer-Attributable Costs + Non-Cancer Attributable Costs = Patient-Liability + Medicare or other primary insurer liability]. Patient-liability is defined as the amount of total health care expenses that are the responsibility of the patient for both cancer attributable and non-cancer health care such as deductibles and `co-pays'. Patient-liability may be paid in part or whole by employer-sponsored supplemental coverage, Medicaid dual-eligibility, or through patient-purchased Medigap coverage).

Calculated using calculated values for 1992 and 2002

The cost of care in the last month of life for an individual diagnosed at age 72 in 2000 was $14,987 for death from lung cancer and $19,173 for death from cardiac causes (Table 2). Over the 10 years of this study, the real (inflation-adjusted) costs of death from lung cancer and cardiac causes (for patients with lung cancer) increased by 7.7% and 21.0%, respectively. For both causes of death, increasing age at diagnosis was associated with a decreased cost of the terminal phase: a reduction of $160 per each additional year of age for lung cancer death, and a reduction of $213 per each additional year of age for cardiac death. Neither age-at-diagnosis nor year-of-diagnosis predicted the cost of operative death (mean $38,088 [SE, $1,150]).

Costs of cancer care

Total costs and patient-share costs for a patient aged 72 in 2000 are provided for the staging phase (Table 3), the initial phase (Table 4), and the continuing care phase (Supplemental Data). Cancer-attributable costs are provided for the initial phase. Significant (p<0.05) terms from linear regressions with age, year of diagnosis, and an interaction term (age*year) are listed with a sign to indicate positive (+) or negative (−) correlations (see Supplemental Data for coefficients).

Table 3.

Average monthly costs (total and patient-liability) for the staging phase by histologic type, stage at diagnosis, and treatment strategy

| Total Cost | Patient-Liability | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-, Year-, standardized (72 yo in 2000) | Significant terms | Age-, Year-, standardized (72 yo in 2000) | Significant terms | |

| NSCLC | ||||

| Stage I and II* | ||||

| No treatment | 10,631 | 1,261 | Year (+) | |

| Radiotherapy | 12,411 | Age (−) | 1,887 | Year (+) |

| Stage III | ||||

| No treatment | 13,404 | 1,444 | Year (+) | |

| Radiotherapy | 14,439 | Age (−) | 2,190 | Year (+) |

| Chemotherapy & Radiotherapy | 14,133 | Year (−) | 2,643 | Age (−), Year (+) |

| Stage IV | ||||

| No treatment | 11,908 | Year (−) | 1,534 | Age (−), Year (+) |

| Radiotherapy | 16,619 | Age (−), Year (+) | 2,370 | Age (−), Year (+) |

| Chemotherapy | 14,062 | Age (−) | 2,305 | Age (−), Year (+) |

| Chemotherapy & Radiotherapy | 16,599 | Age (−) | 2,909 | Age (−), Year (+) |

| SCLC | ||||

| Limited Stage | ||||

| No treatment | 11,279 | Year (−) | 1,398 | Year (+) |

| Chemotherapy | 16,467 | 2,365 | Age (−), Year (+) | |

| Chemotherapy & Radiotherapy | 16,105 | Age (−), Year (−) | 2,702 | Age (−), Year (+) |

| Extensive Stage | ||||

| No treatment | 11,158 | 1,479 | Year (+) | |

| Chemotherapy | 16,309 | Age (−) | 2,433 | Age (−), Year (+) |

| Chemotherapy & Radiotherapy | 17,321 | 2,312 | Year (+) | |

Notes: Not shown are treatment categories with fewer than 10% of patients, see the Supplementary Results for the proportion of patients who received other treatments. Costs are estimated for a 72 year old in year 2000 using the linear regression of the form: Monthly Cost = Constant + βAge *(Age in years) + βYear *(Calendar Year – 1992) + βAge*Year *(Age in years)*(Calendar Year – 1992). Terms were included in the final model using a threshold of α = 0.05. Regression coefficients are presented in Supplementary Table 3A. When no terms were significant, we present the mean over all patients. Total Cost is the sum of average monthly costs from all sources regardless of payer [Total Cost = Cancer-Attributable Costs + Non-Cancer Attributable Costs = Patient-Liability + Medicare or other primary insurer liability]. Patient-liability is defined as the amount of total health care expenses that are the responsibility of the patient for both cancer attributable and non-cancer health care such as deductibles and `co-pays'. Patient-liability may be paid in part or whole by employer-sponsored supplemental coverage, Medicaid dual-eligibility, or through patient-purchased Medigap coverage).

We did not calculate a staging phase for resection surgery because for many patients it overlapped with the month of surgery (median time from diagnosis until surgery was 18 days, see Figure 1B)

Table 4.

Initial phase monthly costs (total, cancer-attributable, and patient-share) by histologic type, stage at diagnosis, and treatment

| Total Cost | Net Cancer Attributable Cost | Patient-Liability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Age-, Year-, standardized (72 yo in 2000) | Significant terms | Age-, Year-, standardized (72 yo in 2000) | Significant terms | Age-, Year-, standardized (72 yo in 2000) | Significant terms | |

| NSCLC | |||||||

| Stage I and II | 10,987 | ||||||

| No treatment | 1,253 (11.4) | 2,687 | 1,779 | 286 | Year (+) | ||

| Surgery* | 5,265 (47.9) | 5,255 | 4,654 | 215 | Year (+) | ||

| Radiotherapy | 2,080 (18.9) | 5,671 | Age (−) | 4,323 | Age (−), Year (−) | 1,148 | Year (+) |

| Stage III | 11,405 | ||||||

| No treatment | 1,723 (15.1) | 3,234 | 2,327 | 275 | Year (+) | ||

| Radiotherapy | 3,014 (26.4) | 5,794 | Age (−) | 4,855 | Age (−), Year (−) | 1,158 | Year (+) |

| Chemotherapy & Radiotherapy | 2,763 (24.2) | 9,257 | Age (−) | 8,752 | Age (−) | 2,004 | Age (−), Year (+) |

| Stage IV | 9,117 | ||||||

| No treatment | 1,269 (13.9) | 3,398 | Age (−) | 2,557 | Age (−) | 264 | Year (+) |

| Radiotherapy | 2,576 (13.1) | 5,391 | Age (−) | 4,857 | Age (−) | 899 | Age (−), Year (+) |

| Chemotherapy | 1,192 (28.3) | 7,677 | Age (−), Year (+) | 7,132 | Age (−), Year (+) | 1,326 | Age (−), Year (+) |

| Chemotherapy & Radiotherapy | 3,209 (35.2) | 8,927 | Age (−), Year (+) | 8,466 | Age (−), Year (+) | 1,698 | Age (−), Year (+) |

| SCLC | |||||||

| Limited Stage | 3,224 | ||||||

| No treatment | 243 (7.5) | 3,565 | 2,680 | 277 | |||

| Chemotherapy | 713 (22.1) | 8,291 | Age (−), Year (+) | 7,533 | Age (−), Year (+) | 1,229 | Year (+) |

| Chemotherapy & Radiotherapy | 1,673 (51.9) | 9,360 | Age (−) | 8,831 | Age (−) | 1,948 | Age (−), Year (+) |

| Extensive Stage | 3,153 | ||||||

| No treatment | 170 (5.4) | 2,878 | 2,182 | 215 | |||

| Chemotherapy | 777 (24.6) | 7,487 | 6,760 | 1,214 | Age (−), Year (+) | ||

| Chemotherapy & Radiotherapy | 1,824 (57.8) | 8,840 | Year (+) | 8,354 | Age (−), Year (+) | 1,617 | Year (+) |

Notes: Not shown are treatment categories with fewer than 10% of patients, see the Supplementary Results for the proportion of patients who received other treatments. Patients who lived fewer than 2 months contributed a month to the staging phase and to the terminal phase but not to the initial phase. Costs are estimated for a 72 year old in year 2000 using the linear regression of the form: Monthly Cost = Constant + βAge *(Age in years) + βYear (Calendar Year – 1992) + βAge*Year *(Age in years)*(Calendar Year – 1992). Terms were included in the final model using a threshold of α= 0.05. Regression coefficients are presented in Supplementary Table 4A. When no terms were significant, we present the mean over all patients. Total Cost is the sum of average monthly costs from all sources regardless of payer [Total Cost = Cancer-Attributable Costs + Non-Cancer Attributable Costs = Patient-Liability + Medicare or other primary insurer liability]. Net Cancer-attributable cost is defined as the individual patient's monthly cost of health care incurred in excess of the average pre-diagnosis cost of health care. Patient-liability is defined as the amount of total health care expenses that are the responsibility of the patient for both cancer attributable and non-cancer health care such as deductibles and `co-pays'. Patient-liability may be paid in part or whole by employer-sponsored supplemental coverage, Medicaid dual-eligibility, or through patient-purchased Medigap coverage).

6 months following surgery month. See Figure 1B.

Staging Phase

For patients who received no treatment, the cost of health care in the month of lung cancer diagnosis ranged from $10,631 to $13,404. After subtracting average pre-diagnosis costs of $645 per month, we can estimate that diagnosis and staging cost $10,000–13,000 in standard clinical practice during the study period. The patient-share cost of health care in the month of lung cancer diagnosis was similar (range, $1,261 to $1,534) across patients who received no treatment, regardless of histologic type or stage of diagnosis.

For patients with NSCLC who received radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, staging phase costs ranged from $12,411 to $16,619 and decreased with age, except for Stage III chemo-radiotherapy. Staging phase costs for treated SCLC patients ranged from $16,105 to 17,321.

The share of staging phase costs paid by beneficiaries increased significantly over the time frame of our analysis for all treatments, histologic types and stages, even when overall staging phase costs remained stable or declined. Among patients who subsequently received active treatment, the patient-share cost was 13.3% to 18.7% of the overall staging phase costs.

Initial Phase

In all cases where age at diagnosis was a significant predictor of initial phase cost, increasing age at diagnosis resulted in a reduction in cost.

Except in one case (Stage IV NSCLC), the initial phase costs for patients who received no treatment were not significantly associated with patient age or year of diagnosis and were similar across histologic-types and stages of diagnosis. The monthly cost of care for patients in the initial phase who received no active treatment (supportive care only) ranged from $2,687 to $3,565, and the lung cancer-attributable portion ranged from $1,779 to $2,680. Monthly patient liability for a typical lung cancer patient receiving no active treatment was similar across histologic types and stages at diagnosis, ranging from $215 to $286 a month, an increase of 2–3 fold over the patient-share of health care costs prior to lung cancer diagnosis.

A 72 year old patient in 2000 receiving an active course of treatment incurred patient-share costs ranging from $899 to $2,004 per month, with the highest burden being incurred by NSCLC patients with Stage III disease receiving chemo-radiotherapy.

Patients receiving chemotherapy and chemo-radiation had high costs in the initial period: monthly cancer-attributable costs for a 72 year old patient diagnosed in 2000 ranged from $6,760 to $8,831 and in most cases increased over time, but decreased with increasing patient age. Radiotherapy costs decreased over time. Patients receiving chemotherapy and chemo-radiation paid high patient-share costs, ranging from $1,214 to $2,004 per month (15–22% of total health care costs). Except for supportive care, patient-share costs increased over time even when the overall costs did not. For example, no increase in costs were observed over time for treating Stage III NSCLC patients with chemo-radiotherapy, yet patients bore an additional monthly cost of $96 with each additional year of diagnosis.

Month of Surgery

Both increasing age at diagnosis (p=0.0021) and earlier year of diagnosis (p<0.0001) were significant predictors of increasing total cost (Table 4B, Supplemental Data). The average lung cancer patient (age 72) diagnosed in 2000 would have incurred approximately $26,235 in health care expenditures in the month of surgery, including $1,400 in patient-share costs. Even though the total cost of health care in the month of surgery decreased by $282 each year (a real decrease of 9% over 10 years), patient-share costs increased $59 with each additional year of diagnosis (a real increase of 57% over 10 years).

Neither overall health care costs ($5,255/month) nor cancer-attributable ($4,654/month) costs beginning 30-days after surgery were predicted by age or year of diagnosis (Table 4). Patient liability costs for those with surgery were similar to those paid by patients who received no treatment ($215/month), and increased over time ($6 per additional year of diagnosis).

Continuing Phase

Similar patterns of change in patient-share costs were observed in the continuing phase of lung cancer treatment as were observed in other periods of care (staging, initial phase and surgery): costs to the patient increased or remained stable over time even when overall health care costs were stable or decreased over time (Supplemental Data).

Discussion

Estimation of medical costs to both Medicare and its beneficiaries is necessary to conduct cost-effectiveness analyses of lung cancer control interventions from the societal perspective, in which all costs are included without regard for who accrues them (18). Distinct from recent publications that estimated annual cancer-related costs to Medicare (7, 19), our cost estimates contribute detail to the literature about financial burdens faced by Medicare beneficiaries treated for lung cancer, the most common cause of cancer death in the U.S. Our estimates provide monthly health care costs (stratified by patient age, phase of care, histologic type, stage at diagnosis and calendar year of diagnosis).

We found that the amount and the proportion of overall costs that are the responsibility of patients increased significantly from 1992 to 2003, even for treatments with stable or decreasing overall costs, thus confirming earlier studies (3, 4) that suggest an increase in cost-shifting to beneficiaries. Among categories in which we observed an increase in the overall cost of health care, the increase in the patient-share costs represented 37.9–95.7% of the total increase in overall costs. The same pattern of an increasing share of costs borne by patients was apparent for most phases of care and most treatment categories. Monthly initial phase costs that were the responsibility of a 72-year old treated in 2000 with combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy were estimated between $1,617 and $2,004, representing 72 to 89% of the median monthly per-capita income for Americans over 65 ($2,258, all in 2006$) (20). Note, however, that patient-liability costs in traditional Medicare are not necessarily paid out-of-pocket by the patient. During the period of this analysis, approximately one-third of beneficiaries had employer-sponsored supplemental coverage that reduced point-of-service obligations, approximately 30% had Medigap coverage, and 20% were dually eligible for Medicaid (21). Medigap is the only supplemental coverage available to all beneficiaries. In 1999, the average annual cost of a Medigap policy was $1,311 per year (22). Consistent with what would be expected as patient-share costs rise, employer sponsored supplemental coverage is decreasing in frequency and in generosity of benefits and the cost of Medigap coverage is increasing (21, 22). Although our analysis excluded beneficiaries without Part B, our findings echo questions raised in prior studies about the affordability of health care for lower-income Medicare beneficiaries (4, 23, 24).

The data do not allow us to determine whether patients chose less effective treatments with lower patient share costs. Lack of patient and physician familiarity with the cost burdens patients face with each treatment option limit the potential for patients to make decisions based on cost. However, if patients become more aware of their payment responsibilities, the repercussions of high out-of-pocket costs could conceivably cause a shift in treatment choice, leading to underuse of recommended services in favor of less effective but more affordable services (25–27). Furthermore, high medical costs can reduce access to health care for other household members (2). Recommended therapies have previously been shown to be less common in under-represented minority groups compared to whites (28–32). Increases in out-of-pocket burdens on low-income patients may result in reduced use of health care services by the economically disadvantaged who are more often members of under-represented minority groups (20), magnifying disparities (33).

Only patients diagnosed with Stage I/II NSCLC followed the classic pattern of higher costs in the initial phase followed by lower costs in the continuing care phase. In part, this may be explained by the short life expectancy associated with lung cancer and our definition of the terminal phase as only the last month of life. The average number of months in the continuing phase was short and many patients were principally in pre-terminal phases that may have included expensive pain control treatments (e.g., fentanyl) or extended palliative care in hospice. We observed a general trend of increasing costs in the terminal phase of care which is consistent with trends of increasing use of aggressive care (ER visits, ICU admissions, systemic therapy) near the end of life in lung cancer and other diseases (8, 34, 35). Consistent with published estimates (36, 37), we found decreasing terminal costs with age.

Pharmaceuticals (over the counter or prescription) were not included in our estimates because 2003 pre-dated Medicare Part D. The time span of the analysis does not cover important treatment advances such as cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy (38) and pre-dated clear-cut evidence of survival benefits from chemotherapy in late stage NSCLC (39). More patients today likely receive chemotherapy or targeted therapies (40, 41). Patient and caregiver time costs and transportation costs to undergo treatment were not available here, but should be included in a cost-effectiveness analysis conducted from the societal perspective. Cancer therapies are increasingly delivered in the outpatient setting, shifting substantial costs to caregivers (13, 42, 43). Despite excluding the 3 months prior to diagnosis, patients in the sample had undiagnosed cancer and could have been receiving treatment related to disease symptoms (44). We defined a 30-day staging phase to isolate staging costs from treatment costs, but this may have miscategorized some staging costs as initial phase costs. Staging costs were not estimated for patients undergoing resection, but the wide variation in staging practices (29, 45) suggests that a micro-costing approach based on procedure codes would be preferable in cost-effectiveness analyses to permit distinction between patient management algorithms.

Other limitations of the analysis include those common to analyses of SEER-Medicare data (14), such as omission of patients younger than 65 and patients enrolled in HMOs. Medicare data are observational and are not collected specifically for health services research, and SEER areas are not entirely representative of the U.S. (14). Our regression analyses were intended to compare time trends in cost components (vs. explaining variability in costs) so did not contain clinical covariates other than age and yielded very small R2 values (Supplemental Data). The total reimbursement amounts are determined by CMS and providers are required by law (with limited exceptions) to collect the full amount (46), although SEER-Medicare files do not contain variables that confirm payment.

The costs of lung cancer care are substantial and our analysis concurs with findings from other studies showing that Medicare beneficiaries are responsible for paying an ever-larger share of the costs (4). Awareness of trends in cost-sharing is important to prevent worsening of sociodemographic disparities in access and quality of care, yet the cost analysis literature contains major gaps (47). Our analysis addressed common limitations of published cost analyses, such as omission of validation studies or technical appendices with sufficient detail to make methods transparent and reproducible.

Supplementary Material

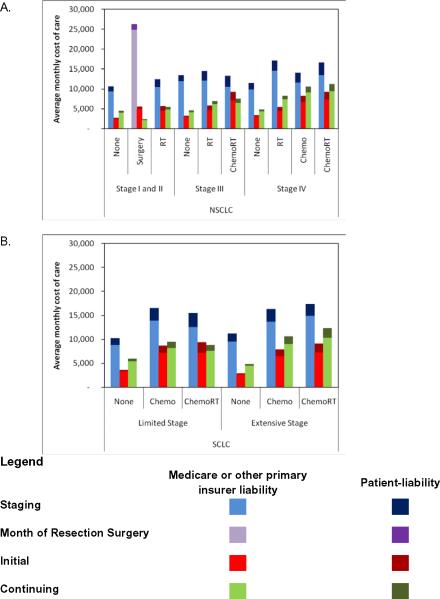

Figure 2.

Average monthly costs (total and patient-liability) for a 72-year old in year 2000 as estimated by linear regression stratified by histologic type, stage at diagnosis, and treatment strategy for (A) NSCLC and (B) SCLC

Table 5.

Continuing phase monthly costs (total, cancer-attributable, patient-share) by histologic type, stage at diagnosis, and treatment

| Total Cost | Net Cancer Attributable Cost | Patient-Share Cost | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Age-, Year-, standardized (72 yo in 2000) | Significant terms | Age-, Year-, standardized (72 yo in 2000) | Significant terms | Age-, Year-, standardized (72 yo in 2000) | Significant terms | |

| NSCLC | |||||||

| Stage I and II | 7,521 | ||||||

| No treatment | 665 (8.8) | 4,498 | 3,721 | 414 | Year (+) | ||

| Surgery* | 4,335 (57.6) | 2,602 | Year (−) | 1,996 | Year (−) | 341 | |

| Radiotherapy | 1,079 (14.3) | 5,403 | 4,428 | 590 | Age Age (−), Year (+) | ||

| Stage III | 5,364 | ||||||

| No treatment | 663c (12.4) | 5,139 | Year (−) | 4,313 | Year (−) | 422 | |

| Radiotherapy | 1,176 (21.9) | 6,941 | 6,309 | 762 | Age Age (−), Year (+) | ||

| Chemotherapy & Radiotherapy | 1,302 (24.3) | 8,196 | Year (−) | 7,758 | Year (−) | 1,073 | Age Age (−) |

| Stage IV | 2,924 | ||||||

| No treatment | 334 (11.4) | 5,538 | Age Age (−), Year (−), Age*Year (+) | 4,733 | Age Age (−), Year (−), Age*Year (+) | 451 | |

| Radiotherapy | 598 (20.5) | 8,287 | Age Age (−) | 7,789 | Age Age (−) | 807 | Year (+) |

| Chemotherapy | 411 (14.1) | 10,026 | 9,425 | 1,465 | Age Age (−) | ||

| Chemotherapy & Radiotherapy | 1,215 (41.6) | 11,178 | Age Age (−) | 10,767 | Age Age (−) | 1,609 | Age Age (−), Year (+) |

| SCLC | |||||||

| Limited Stage | 1,732 | ||||||

| No treatment | 100 (5.8) | 5,975 | 5,127 | 583 | |||

| Chemotherapy | 336 (19.4) | 9,445 | 8,834 | 1,296 | |||

| Chemotherapy & Radiotherapy | 972 (56.1) | 8,807 | 7,922 | Year (−) | 1,20 | ||

| Extensive Stage | 1,392 | ||||||

| No treatment | 51 (3.7) | 4,850 | 4,507 | 380 | |||

| Chemotherapy | 285 (20.5) | 10,660 | 9,941 | 1,541 | Year (+) | ||

| Chemotherapy & Radiotherapy | 914 (65.7) | 12,344 | 11,829 | 1,900 | Year (+) | ||

Notes: Not shown are treatment categories with fewer than 10% of patients, see the Supplementary Results for the proportion of patients who received other treatments. Patients who lived between 2 and 7 months contributed a month to the staging phase and to the terminal phase and between 1 and 6 months to the initial phase, but no months to the continuing phase. Costs are estimated for a 72 year old in year 2000 using the linear regression of the form: Monthly Cost = Constant + βAge *(Age in years) + βYear *(Calendar Year – 1992) + βAge*Year *(Age in years)*(Calendar Year – 1992). Terms were included in the final model using a threshold of α = 0.05. Regression coefficients are presented in Supplementary Table 5A. When no terms were significant, we present the mean over all patients. Total Cost is the sum of average monthly costs from all sources regardless of payer [Total Cost = Cancer-Attributable Costs + Non-Cancer Attributable Costs = Patient-Liability + Medicare or other primary insurer liability]. Net Cancer-attributable cost is defined as the individual patient's monthly cost of health care incurred in excess of the average pre-diagnosis cost of health care. Patient-liability is defined as the amount of total health care expenses that are the responsibility of the patient for both cancer attributable and non-cancer health care such as deductibles and `co-pays'. Patient-liability may be paid in part or whole by employer-sponsored supplemental coverage, Medicaid dual-eligibility, or through patient-purchased Medigap coverage).

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Gerald Riley, M.S.P.H., Office of Research, Development, and Information, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and Elizabeth Lamont, MD, for helpful suggestions.

This project was funded by the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA97337 [Gazelle], K99 CA126147 [McMahon]).

References

- 1.Brown ML, Riley GF, Schussler N, et al. Estimating health care costs related to cancer treatment from SEER-Medicare data. Med Care. 2002;40:IV, 104–17. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langa KM, Fendrick AM, Chernew ME, et al. Out-of-pocket health-care expenditures among older Americans with cancer. Value in Health. 2004;7:186–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.72334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neuman P, Cubanski J, Desmond KA, et al. How much `skin in the game' do Medicare beneficiaries have? The increasing financial burden of health care spending, 1997–2003. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:1692–701. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riley GF. Trends in out-of-pocket healthcare costs among older community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:692–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts and Figures, 2008. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100:630–41. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warren JL, Yabroff KR, Meekins A, et al. Evaluation of trends in the cost of initial cancer treatment. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100:888–97. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodward RM, Brown ML, Stewart ST, et al. The value of medical interventions for lung cancer in the elderly - Results from SEER-CMHSF. Cancer. 2007;110:2511–18. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker MS, Kessler LG, Urban N, et al. Estimating the treatment costs of breast and lung cancer. Med Care. 1991;29:40–9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199101000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fireman BH, Quesenberry CP, Somkin CP, et al. Cost of care for cancer in a health maintenance organization. Health Care Financ Rev. 1997;18:51–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riley G, Potosky A, Lubitz J, et al. Medicare payments from diagnosis to death for elderly cancer patients by stage at diagnosis. Medical Care. 1995;33:828–41. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199508000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taplin S, Barlow W, Urban N, et al. Stage, age, comorbidity, and direct costs of colon, prostate, and breast cancer care. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1995;87:417–26. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.6.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yabroff KR, Warren JL, Brown ML. Costs of cancer care in the USA: a descriptive review. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:643–56. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, et al. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Medical Care. 2002;40:IV-3–IV-18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Cancer Institute . Technical Notes: The SEER Program. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etzioni R, Riley GF, Ramsey SD, et al. Measuring costs: administrative claims data, clinical trials, and beyond. Medical Care. 2002;40:III63–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai J, Houseman E, Gelber RD, et al. Estimating the counterfactual cost of metastatic lung cancer using administrative claims data. International Conference on Health Policy Research; Chicago, IL: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, et al. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. Oxford University Press; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yabroff KR, Bradley CJ, Mariotto AB, et al. Estimates and projections of value of life lost from cancer deaths in the United States. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100:1755–62. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2007. Current Population Reports. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, D.C.: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.United States General Accounting Office . Retiree Health Benefits. Report to the Chairman, Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, US Senate. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.United States General Accounting Office . Medigap: Current Policies Contain Coverage Gaps, Undermine Cost Control Incentives. Testimony before the Subcommittee on Health, Committee on Ways and Means, House of Representatives. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gross DJ, Alecxih L, Gibson MJ, et al. Out-of-pocket health spending by poor and near-poor elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res. 1999;34:241–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Federman AD, Adams AS, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Supplemental insurance and use of effective cardiovascular drugs among elderly Medicare beneficiaries with coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2001;286:1732–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chernew ME, Rosen AB, Fendrick AM. Rising out-of-pocket costs in disease management programs. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12:150–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathews M, West R, Buebler S. How important are out-of-pocket costs to rural patients' cancer care decisions? Can J Rural Med. 2009;14:54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meropol NJ, Schulman KA. Cost of Cancer Care: Issues and Implications. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:180–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bach PB, Cramer LD, Warren JL, et al. Racial differences in the treatment of early-stage lung cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 1999;341:1198–205. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lathan CS, Neville BA, Earle CC. The effect of race on invasive staging and surgery in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:413–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potosky AL, Saxman S, Wallace RB, et al. Population variations in the initial treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:3261–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Earle CC, Venditti LN, Neumann PJ, et al. Who gets chemotherapy for metastatic lung cancer? Chest. 2000;117:1239–46. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neighbors CJ, Rogers ML, Shenassa ED, et al. Ethnic/racial disparities in hospital procedure volume for lung resection for lung cancer. Med Care. 2007;45:655–63. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180326110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chernew M, Fendrick AM. Value and increased cost sharing in the American health care system. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:451–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:315–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma G, Freeman J, Zhang D, et al. Trends in end-of-life ICU use among older adults with advanced lung cancer. Chest. 2008;133:72–78. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levinsky NG, Yu W, Ash A, et al. Influence of age on Medicare expenditures and medical care in the last year of life. Jama. 2001;286:1349–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hogan C, Lunney J, Gabel J, et al. Medicare beneficiaries' costs of care in the last year of life. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:188–95. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.4.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Chevalier T, Lynch T. Adjuvant treatment of lung cancer: current status and potential applications of new regimens. Lung Cancer. 2004;46:S33–9. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(04)80039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breathnach O, Freidlin B, Conley B, et al. Twenty-two years of phase III trials for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Sobering results. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:1734–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waechter F, Passweg J, Tamm M, et al. Significant progress in palliative treatment of non-small cell lung cancer in the past decade. Chest. 2005;127:738–47. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.3.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J, Kuo YF, Freeman J, et al. Temporal trends and predictors of perioperative chemotherapy use in elderly patients with resected nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:382–90. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayman JA, Langa KM, Kabeto MU, et al. Estimating the cost of informal caregiving for elderly patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3219–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman J, et al. Assistance from family members, friends, paid care givers, and volunteers in the care of terminally ill patients. The New England journal of medicine. 1999;341:956–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909233411306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spiro SG, Gould MK, Colice GL. Initial Evaluation of the Patient With Lung Cancer: Symptoms, Signs, Laboratory Tests, and Paraneoplastic Syndromes: ACCP Evidenced-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (2nd Edition) Chest. 2007;132:149S–60. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whitson BA, Groth SS, Maddaus MA. Surgical assessment and intraoperative management of mediastinal lymph nodes in non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1059–65. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.42CFR: Public Health. 42. Code of Federal Regulations. GPO Access; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lipscomb JP, Yabroff KRP, Brown MLP, et al. Health Care Costing: Data, Methods, Current Applications. Medical Care. 2009;47:S1–S6. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a7e401. Miscellaneous. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.