Abstract

The Schiff bases HL1-3 have been prepared by the reaction of 5-bromothiophene-2-carboxaldehyde with 4-amino-5-mercapto-3-methyl/propyl/isopropyl-s-triazole, respectively. Organosilicon(IV) and organotin(IV) complexes of formulae (CH3)2MCl(L1-3), (CH3)2M(L1-3)2 were synthesized from the reaction of (CH3)2MCl2 and the Schiff bases in 1 : 1 and 1 : 2 molar ratio, where M = Si and Sn. The synthesized Schiff bases and their metal complexes have been characterized with the aid of various physicochemical techniques like elemental analyses, molar conductance, UV, IR, 1H, 13C, 29Si, and 119Sn NMR spectroscopy. Based on these studies, the trigonal bipyramidal and octahedral geometries have been proposed for these complexes. The ligands and their metal complexes have been screened in vitro against some bacteria and fungi.

1. Introduction

Recently, the research relating with metal complexes of heteronuclear Schiff bases has expanded enormously and now comprising their interesting aspects in coordination chemistry with a special emphasis in bioinorganic chemistry. A use of organosilicon and organotin compounds as reagents or intermediates in the inorganic synthesis has further strengthened their applications [1, 2].

More-over, metal complexes of organosilicon(IV) and organotin(IV) halides with N, O, and S donor ligands have received much more consideration due to their industrial, environmental, and biological applications [3–5]. The N, O and S donor ligands have been used to enhance the biological activity of organosilicon and organotin derivatives [6]. Organosilicon(IV) complexes have been subjected of interest for their versatile applications in pharmaceutical and chemical industries. Organosilicon compounds of nitrogen and sulphur containing ligands are well known for their anticarcinogenic, antibacterial, antifungal, tuberculostatic, insecticidal, and acaricidal activities [7–10]. Generally, organosilicon complexes seem to owe their antitumor properties to the immune-defensive system of the organism [11]. Similarly, organotin compounds are the active components in a number of biocidal formulations in such diverse areas as fungicides, miticides, molluscicides, antifouling paints and surface disinfectants [12, 13]. In addition, many organotin compounds have been tested for a large variety of tumor lines and found to be more effective than traditional heavy metal anticancer drugs [14, 15]. Ahmad et al. have also screened some organotin compounds against tumor cells [16]. Prompted by these applications, few new organosilicon and organotin compounds have already been synthesized and screened for antibacterial and antifungal activities [17, 18], and in continuation to this, in the present paper, the synthesis, characterization, and biological activities of new triazole Schiff bases and their organosilicon and organotin complexes have been carried out.

2. Experimental

Dried solvents were used for the synthesis of compounds. Reagents, 5-bromothiophene-2-carboxaldehyde (Spectrochem), Dimethylsilicon-dichloride (Acros) and Dimethyltindichloride (TCI-America) were used as such.

2.1. Analytical Methods and Physical Measurements

Silicon and tin were determined gravimetrically as silicondioxide (SiO2) and tindioxide (SnO2). Melting points were determined on a capillary melting point apparatus. Molar conductance measurements of 10−3 M solution of metal complexes in dry DMF were measured at room temperature (25 ± 1°C) with a conductivity bridge type 305 Systronic model. Carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and sulfur were estimated using elemental analyzer Heraeus Vario EL-III Carlo Erba 1108 at CDRI Lucknow. The electronic spectra of the ligands and their metal complexes were recorded in dry methanol, on a Systronics, Double-beam spectrophotometer 2203, in the range of 600–200 nm. The IR spectra of the ligands and metal complexes were recorded in nujol mulls/KBr pellets using BUCK scientific M5000 grating spectrophotometer in the range of 4000–350 cm−1. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectra (1H, 13C) were recorded on BRUKER-300ACF and 29Si and 119Sn were recorded on BRUKER-400ACF spectrometer in DMSO-d6 using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard.

2.2. Synthesis of Ligands

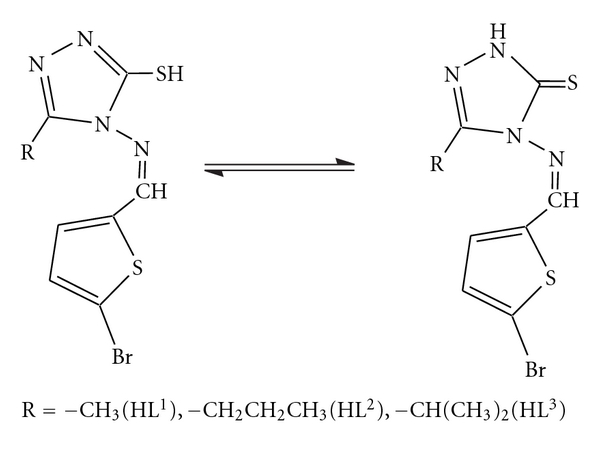

4-Amino-5-mercapto-3-methyl-s-triazole (AMMT), 4-amino-5-mercapto-3-propyl-s-triazole (AMPT) and 4-amino-3-isoproyl-5-mercapto-s-triazole (AIMT) were synthesized by reported methods [19, 20]. The ligands were synthesized by condensation of 5-bromothiophene-2-carboxaldehyde with AMMT, AMPT and AIMT in the medium of ethanol (Figure 1). The contents were refluxed for 4–5 h in absolute ethanol. After refluxing, the reaction mixture was kept overnight at room temperature and the product was filtered, washed, and recrystallized from same solvent. The elemental analyses and physical properties of the ligands are reported in Table 1. The three ligands are: HL1 = 4-(5-Bromothiophen-2-carboxylidene amino)-3-methyl-5-mercapto-s-triazole (BTMMT), HL2 = 4-(5-Bromothiophen-2-carboxylidene amino)-5-mercapto-3-propyl-s-triazole (BTMPT), HL3 = 4-(5-Bromothiophen-2-carboxylidene amino)-3-isopropyl-5-mercapto-s-triazole (BTIMT).

Figure 1.

Structure of Schiff bases, where R = –CH3, HL1 = 4-(5-Bromothiophen-2-carboxylidene amino)-3-methyl-5-mercapto-s-triazole (BTMMT); R = –CH2–CH2–CH3, HL2 = 4-(5-Bromothiophen-2-carboxylidene amino)-5-mercapto-3-propyl-s-triazole (BTMPT); R = –CH(CH3)2, HL3 = 4-(5-Bromothiophen-2-carboxylidene amino)-3-isopropyl-5-mercapto-s-triazole (BTIMT).

Table 1.

Physical characteristics and analytical data of ligands and their metal complexes.

| Compound | Empirical formulae | Color | Decomposition Temp. (°C) | Molar conductance (Ω−1 cm2 mol−1) | Found (Calc.)% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | N | S | Si/Sn | |||||

| HL1(BTMMT) | C8H7BrN4S2 | Light Brown | 182 | — | 31.02 (31.69) | 2.43 (2.33) | 18.64 (18.48) | 21.21 (21.15) | — |

| Me2SiCl(L1) | C10H12BrClN4S2Si | Brown | 176 | 15.46 | 30.04 (29.44) | 3.21 (3.05) | 14.43 (14.24) | 16.12 (16.20) | 7.12 (7.10) |

| Me2Si(L1)2 | C18H18Br2N8S4Si | Light Yellow | 220 | 11.24 | 32.21 (32.63) | 2.87 (2.74) | 16.78 (16.91) | 19.32 (19.36) | 4.25 (4.24) |

| Me2SnCl(L1) | C10H12BrClN4S2Sn | Yellow | 222 | 14.82 | 24.98 (24.69) | 2.65 (2.49) | 11.44 (11.52) | 13.19 (13.18) | 24.35 (24.40) |

| Me2Sn(L1)2 | C18H18Br2N8S4Sn | Light Yellow | 238 | 10.78 | 28.64 (28.70) | 2.44 (2.41) | 14.34 (14.88) | 17.06 (17.03) | 15.74 (15.76) |

| HL2(BTMPT) | C10H11BrN4S2 | Dark Brown | 178 | — | 36.84 (36.26) | 3.66 (3.35) | 16.79 (16.91) | 19.42 (19.36) | — |

| Me2SiCl(L2) | C12H16BrClN4S2Si | Brown | 172 | 15.98 | 34.42 (34.00) | 3.54 (3.80) | 13.42 (13.22) | 15.21 (15.13) | 6.67 (6.63) |

| Me2Si(L2)2 | C22H26Br2N8S4Si | White | 234 | 11.43 | 36.21 (36.77) | 3.55 (3.65) | 15.61 (15.59) | 17.57 (17.85) | 3.89 (3.91) |

| Me2SnCl(L2) | C12H16BrClN4S2Sn | White | 224 | 14.52 | 28.76 (28.01) | 3.24 (3.13) | 10.02 (10.08) | 12.51 (12.47) | 23.10 (23.07) |

| Me2Sn(L2)2 | C22H26Br2N8S4Sn | White | 260 | 10.54 | 32.42 (32.65) | 3.12 (3.24) | 13.58 (13.85) | 15.81 (15.85) | 14.65 (14.67) |

| HL3(BTIMT) | C10H11BrN4S2 | Light Brown | 174 | — | 36.44 (36.26) | 3.36 (3.35) | 16.96 (16.91) | 19.38 (19.36) | — |

| Me2SiCl(L3) | C12H16BrClN4S2Si | Pale Yellow | 244 | 15.88 | 34.06 (34.00) | 3.70 (3.80) | 13.44 (13.22) | 15.18 (15.13) | 6.67 (6.63) |

| Me2Si(L3)2 | C22H26Br2N8S4Si | Light Yellow | 252 | 11.47 | 36.44 (36.77) | 3.46 (3.65) | 15.62 (15.59) | 17.79 (17.85) | 3.89 (3.91) |

| Me2SnCl(L3) | C12H16BrClN4S2Sn | Dark Brown | 262 | 13.49 | 28.12 (28.01) | 3.42 (3.13) | 10.10 (10.08) | 12.42 (12.47) | 23.10 (23.07) |

| Me2Sn(L3)2 | C22H26Br2N8S4Sn | Light Yellow | 272 | 10.21 | 32.42 (32.65) | 3.27 (3.24) | 13.72 (13.85) | 15.91 (15.85) | 14.69 (14.67) |

2.3. Synthesis of Metal Complexes

To a weighed amount of dimethylsilicondichloride (Me2SiCl2) and dimethyltindichloride (Me2SnCl2) in ~30 mL of dry methanol, was added the calculated amount of the sodium salt of the ligands in 1 : 1 and 1 : 2 molar ratios. The sodium salts of the ligands were prepared by dissolving the appropriate amount of the sodium metal and ligands in ~30 mL dry methanol. The reaction mixture was refluxed for about 12 h and then allowed to cool at room temperature and removed the chlorine as sodium chloride. The excess of solvent was removed under reduced pressure by vacuum pump and the resulting solid was repeatedly washed with 5–10 mL dry cyclohexane and again dried under vacuum. The elemental analyses and physical properties of the complexes are reported in Table 1.

3. Results and Discussion

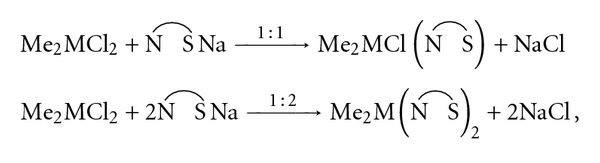

The reactions of Me2SiCl2 and Me2SnCl2 with the sodium salt of monobasic bidentate ligands in 1 : 1 and 1 : 2 molar ratios in methanol medium result in the precipitation of sodium chloride (NaCl), as shown by following reactions:

|

(1) |

where M = Si or Sn and N S represent the donor sites of the ligands.

The resulting complexes have been obtained as coloured solids which are soluble in DMSO, DMF, and MeOH. The ligands show a sharp melting point, but the complexes decompose in a range of temperature (200–300°C). The molar conductivity values measured for 10−3 M solutions in anhydrous DMF are in the range of 10–16 Ω−1cm2 mol−1, showing that all 1 : 1 and 1 : 2 complexes are nonelectrolytic in nature Table 1.

3.1. Electronic Spectra

The electronic spectra of the ligands HL1−3 and their corresponding Si(IV) and Sn(IV) metal complexes were recorded. The electronic spectra of ligands HL1, HL2, and HL3 exhibit maxima at 388 nm, 364 nm, and 387 nm, respectively, which could be assigned to the n-π* transition of the azomethine group. These bands show a blue shift in 1 : 1 and 1 : 2, Si(IV) and Sn(IV) metal complexes and appear at 368 nm, 369 nm, 358 nm, 369 nm, 362 nm, 364 nm, 359 nm, 362 nm, 372 nm, 368 nm, 376 nm and 366 nm for Me2SiCl(L1), Me2Si(L1)2, Me2SnCl(L1), Me2Sn(L1)2, Me2SiCl(L2), Me2Si(L2)2, Me2SnCl(L2), Me2Sn(L2)2, Me2SiCl(L3), Me2Si(L3)2, Me2SnCl(L3), and Me2Sn(L3)2, respectively, and indicating the coordination of azomethine nitrogen atom to the metal atom [16]. In addition to this, the three medium intensity bands at 244 nm, 240 nm, and 260 nm due to π-π* transition in the ligands remain unchanged or show a minor change in the spectra of metal complexes [17].

3.2. IR Spectra

In the IR spectra of the ligands, a broad band in the region of 3117–3094 cm−1 due to ν(N–H) [13] and a band at ~1120 cm−1 due to ν(C=S) [21], indicating the thione form, while a weak band observed around 2750 cm−1 due to ν(S–H) vibrations suggested that the Schiff bases exhibit thiol-thione tautomerism (Figure 1) [22, 23]. The deprotonation of −SH group of triazole was indicated by the absence of bands in the spectra of metal complexes due to ν(S–H), ν(C=S), and ν(N–H). A new band appears ~740 cm−1 in the spectra of the complexes, which is assigned to ν(C–S) and which indicates the complexation of ligands through S-atom with the metal atom. The metal sulphur bond formation is further supported by a band at ~452 cm−1 and ~426 cm−1 for ν(Si–S) [24] and ν(Sn–S) [25] in the spectra of organosilicon and organotin complexes, respectively. A sharp and strong band in the region of 1582–1597 cm−1 for ν(N=CH) [26] in case of ligands, was shifted to a higher wavelength number and appears in the region of 1628–1674 cm−1 in the spectra of metal complexes, indicating the coordination of ligands through azomethine nitrogen to the metal atom. The metal nitrogen bond was further supported by the presence of a band at about ~535 cm−1 for ν(Sn–N) [27] and ~575 cm−1 for ν (Si–N) [28]. A strong band in the region of 425–378 cm−1 was assigned to ν(M–Cl) [29]. The IR-spectral data of the ligands and their metal complexes are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

IR-spectroscopic data (cm−1) of the ligands and their metal complexes.

| Compound | ν(N–H) | ν(–C=N) | ν(C=S)a/ν(C–S)b | ν(S–H) | ν(M–S) | ν(M–N) | ν(M–Cl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HL1(BTMMT) | 3117 | 1597 | 1173 | 2754 | — | — | — |

| Me2SiCl(L1) | — | 1628 | 717 | — | 453 | 572 | 418 |

| Me2Si(L1)2 | — | 1628 | 710 | — | 458 | 576 | — |

| Me2SnCl(L1) | — | 1643 | 741 | — | 403 | 528 | 378 |

| Me2Sn(L1)2 | — | 1643 | 741 | — | 416 | 538 | — |

| HL2(BTMPT) | 3109 | 1589 | 1111 | 2754 | — | — | — |

| Me2SiCl(L2) | — | 1636 | 702 | — | 452 | 570 | 420 |

| Me2Si(L2)2 | — | 1697 | 741 | — | 446 | 582 | — |

| Me2SnCl(L2) | — | 1674 | 741 | — | 416 | 542 | 396 |

| Me2Sn(L2)2 | — | 1674 | 733 | — | 418 | 543 | — |

| HL3(BTIMT) | 3094 | 1582 | 1126 | 2777 | — | — | — |

| Me2SiCl(L3) | — | 1655 | 756 | — | 456 | 563 | 426 |

| Me2Si(L3)2 | — | 1659 | 741 | — | 452 | 578 | — |

| Me2SnCl(L3) | — | 1651 | 764 | — | 410 | 536 | 395 |

| Me2Sn(L3)2 | — | 1659 | 733 | — | 416 | 544 | — |

a = Ligands.

b = Complexes.

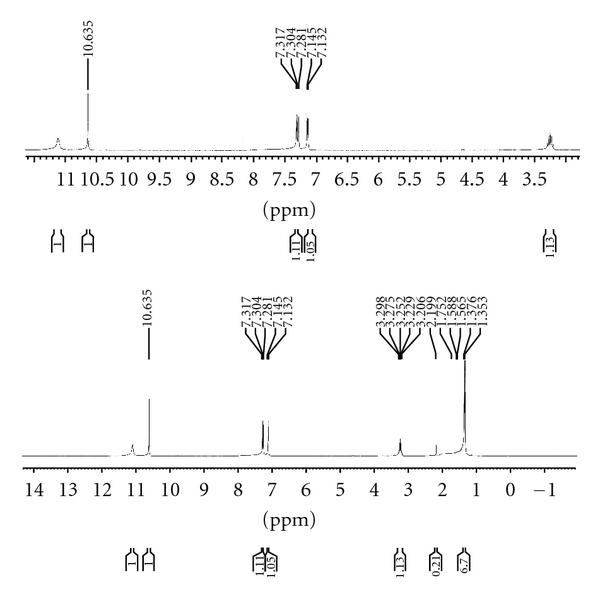

3.3. 1H NMR Spectra

The 1H NMR spectra of the ligands show the –SH proton signal at δ 10.47 (s), δ 13.75 (s), and δ 11.10 (s) ppm for HL1, HL2, and HL3, respectively [26] (Figure 2). The disappearance of the signal due to –SH proton in the spectra of metal complexes indicates the deprotonation of the thiol group and supports the coordination of ligand through sulphur atom to the metal atom. A signal at δ 11.72 (s), 10.91 (s), and 10.63 (s) ppm was observed due to azomethine proton in the spectra of free ligands HL1, HL2 and HL3, respectively, which moves upfield in the 1H NMR spectra of metal complexes [13], indicates the bonding through the azomethine nitrogen atom to the central metal atom (Figure 3). The aromatic protons of the thiophene moiety in the ligands appear as two doublets, which remain more or less unchanged in the 1H NMR spectra of the metal complexes. Some additional signals at δ 2.45 ppm (s, CH3, Triazole), δ 2.78 ppm (t, CH2–CH2–CH3, Triazole), δ 1.69–1.63 ppm (m, CH2–CH2–CH3, Triazole), δ 1.03 ppm (t, CH2–CH2–CH3, Triazole), δ 3.29–3.20 ppm (CH(CH3)2, Triazole), δ 1.36 ppm (d, CH(CH3)2, Triazole) and also appeared in the 1HNMR spectra of the ligands, and their metal complexes, reported in the Table 3. The additional signals in the region δ 0.3–1.5 ppm are also observed in the spectra of complexes due to CH3–M group.

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectrum of Schiff base (HL3).

Figure 3.

1H NMR spectrum of Si (1 : 1) metal complex of ligand (HL3).

Table 3.

1HNMR chemical shifts of the ligands and their metal complexes.

| Compound | –CH=N | –SH | Aromatic-H | Triazole-CH3, –CH2–CH2–CH3, –CH(CH3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HL1(BTMMT) | 11.70 (s) | 10.47 (s) | 7.30 (d, 1H, J = 3.6 Hz); 7.13 (d, 1H, J = 3.6 Hz) |

2.45 (s, 3H) |

| Me2SiCl(L1) | 9.64 (s) | — | 7.35 (d, 1H, J = 3.9 Hz); 7.14 (d, 1H, J = 3.9 Hz) |

2.42 (s, 3H) |

| Me2Si(L1)2 | 11.12 (s) | — | 7.42 (d, 2 H, J = 3.9 Hz); 7.31 (d, 2 H, J = 3.9 Hz) |

2.19 (s, 6H) |

| Me2SnCl(L1) | 11.19 (s) | — | 7.26 (d,1H, J = 3.0 Hz); 7.14 (d, 1H, J = 3.0 Hz) |

2.22 (s, 3H) |

| Me2Sn(L1)2 | 11.15 (s) | — | 7.36 (d, 2H, J = 3.0 Hz); 7.29 (d, 2H, J = 3.0 Hz) |

2.10 (s, 6H) |

| HL2(BTMPT) | 10.91 (s) | 13.75 (s) | 7.31 (d, 1H, J = 3.6 Hz); 7.13 (d, 1H, J = 3.6 Hz) |

2.78 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz); 1.69–1.63 (m, 2H); 1.03 (t, 3H, J = 7.5 Hz) |

| Me2SiCl(L2) | 10.41 (s) | — | 7.44 (d, 1H, J = 3.9 Hz); 7.19 (d, 1H, J = 3.9 Hz) |

2.64 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz); 1.79–1.61(m, 2H); 0.94 (t, 3H, J = 7.5 Hz) |

| Me2Si(L2)2 | 8.41 (s) | — | 7.43 (d, 2H, J = 3.9 Hz); 7.21 (d, 2H, J = 3.9 Hz) |

2.63 (t, 4H, J = 7.5 Hz); 1.65–1.48 (m, 4H); 0.96 (t, 6H, J = 7.5 Hz) |

| Me2SnCl(L2) | 8.49 (s) | — | 7.20 (d, 1H, J = 3.9 Hz); 6.88 (d, 1H, J = 3.9 Hz) |

2.62 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz); 1.79–1.56 (m, 2H); 0.94 (t, 3H, J = 7.5 Hz) |

| Me2Sn(L2)2 | 8.87 (s) | — | 7.36 (d, 2H, J = 3.6 Hz); 7.35 (d, 2H, J = 3.6 Hz) |

2.68 (t, 4H, J = 7.2 Hz); 1.99–1.97 (m, 4H); 1.25 (t, 6H, J = 7.2 Hz) |

| HL3(BTIMT) | 10.63 (s) | 11.10 (s) | 7.31(d, 1H, J = 3.9 Hz); 7.13 (d, 1H, J = 3.9 Hz) |

3.29–3.20 (m, 1H); 1.36 (d, 6H, J = 6.9 Hz) |

| Me2SiCl(L3) | 10.32 (s) | — | 7.51 (d, 1H, J = 3.6 Hz); 7.23 (d, 1H, J = 3.6 Hz) |

3.28–3.12 (m, 1H,); 1.25 (d, 6H, J = 7.2 Hz) |

| Me2Si(L3)2 | 8.44 (s) | — | 7.10 (d, 2H, J = 3.9 Hz); 7.02 (d, 2H, J = 3.9 Hz) |

3.14–2.86 (m, 2H); 1.25 (d,12H, J = 7.2 Hz) |

| Me2SnCl(L3) | 8.40 (s) | — | 7.12 (d, 1H, J = 3.9 Hz); 7.08 (d, 1H, J = 3.9 Hz) |

2.87–2.73 (m, 1 H); 1.17 (d, 6 H, J = 7.2 Hz) |

| Me2Sn(L3)2 | 8.48 (s) | — | 7.10 (d, 2H, J = 3.9 Hz); 7.09 (d, 2H, J = 3.9 Hz) |

2.92–2.83 (m, 2H); 1.18 (d,12H, J = 7.2 Hz) |

3.4. 13C NMR Spectra

The 13C NMR spectral data of ligands HL1, HL2, and HL3, and their corresponding 1 : 1 and 1 : 2 metal complexes [17, 18] have been reported in Table 4. The signal due to the carbon atom attached to the azomethine group in the ligands HL1, HL2, and HL3 appear at δ 166.42 ppm, δ 162.23 ppm, and δ 160.79 ppm, respectively. However, in the spectra of the corresponding metal complexes, the shift in the 13C resonance indicate the coordination of nitrogen atom of azomethine group with the central atom in 1 : 1 and 1 : 2 metal complexes. Moreover, the shifting of the 13C resonance of triazole which is attached to sulphur atom in the spectra of 1 : 1 and 1 : 2 metal complexes compared to the free ligands indicates the coordination through sulphur atom with the central metal atom. The new signal due to the methyl groups attached to the metal atom in the spectra of metal complexes has also been reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

C13 NMR chemical shifts of the ligands and their metal complexes.

| Compound | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 | C10 | M–CH3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HL1(BTMMT) | 124.05 | 135.85 | 139.06 | 143.92 | 166.42 | 153.51 | 157.32 | 15.67 | — | — | — |

| Me2SiCl(L1) | 131.77 | 132.39 | 137.24 | 137.94 | 183.07 | 138.32 | 156.08 | 9.5 | — | — | 18.11 |

| Me2Si(L1)2 | 116.70 | 132.06 | 133.60 | 141.23 | 160.96 | 147.79 | 149.04 | 11.32 | — | — | 28.22 |

| Me2SnCl(L1) | 120.65 | 132.03 | 132.98 | 142.52 | 162.54 | 147.89 | 148.26 | 11.65 | — | — | 30.11 |

| Me2Sn(L1)2 | 116.03 | 131.94 | 132.82 | 141.82 | 161.23 | 147.33 | 147.58 | 11.37 | — | — | 32.11 |

| HL2(BTMPT) | 120.15 | 131.09 | 134.59 | 138.97 | 162.23 | 152.73 | 152.92 | 13.69 | 19.29 | 26.91 | — |

| Me2SiCl(L2) | 119.30 | 131.84 | 135.64 | 139.04 | 183.06 | 154.32 | 156.02 | 13.76 | 19.44 | 26.81 | 18.23 |

| Me2Si(L2)2 | 128.18 | 129.28 | 131.98 | 141.72 | 161.81 | 153.26 | 154.25 | 14.58 | 19.02 | 25.95 | 24.66 |

| Me2SnCl(L2) | 126.23 | 128.56 | 131.23 | 140.58 | 162.48 | 152.56 | 154.85 | 14.23 | 18.65 | 26.42 | 31.32 |

| Me2Sn(L2)2 | 124.26 | 130.45 | 132.05 | 141.62 | 161.98 | 153.26 | 154.26 | 14.42 | 18.87 | 26.86 | 32.00 |

| HL3(BTIMT) | 124.18 | 135.96 | 139.22 | 143.95 | 160.79 | 157.86 | 157.26 | 30.27 | 24.44 | 24.44 | — |

| Me2SiCl(L3) | 118.67 | 132.03 | 135.82 | 139.08 | 161.95 | 154.71 | 154.98 | 25.56 | 19.79 | 19.79 | 19.12 |

| Me2Si(L3)2 | 120.42 | 129.45 | 133.25 | 138.55 | 160.78 | 152.53 | 151.25 | 28.45 | 20.25 | 22.76 | 29.10 |

| Me2SnCl(L3) | 122.62 | 128.46 | 132.46 | 139.42 | 161.86 | 153.24 | 154.25 | 27.56 | 19.45 | 24.57 | 29.88 |

| Me2Sn(L3)2 | 124.56 | 130.54 | 135.03 | 141.21 | 162.46 | 154.48 | 153.24 | 28.89 | 21.22 | 26.43 | 31.89 |

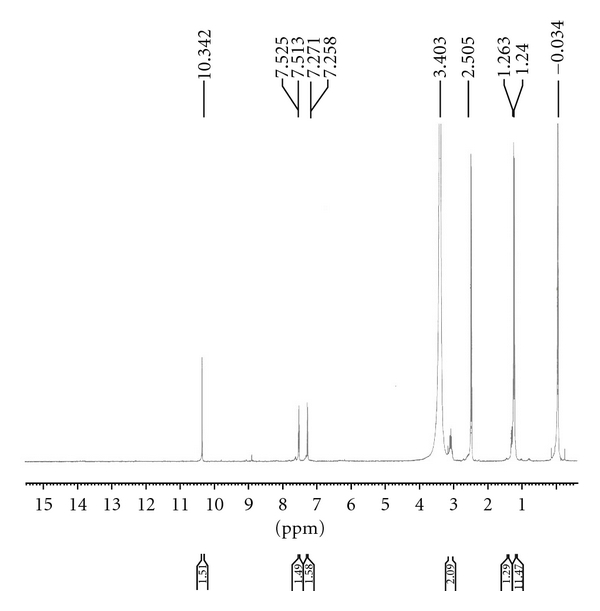

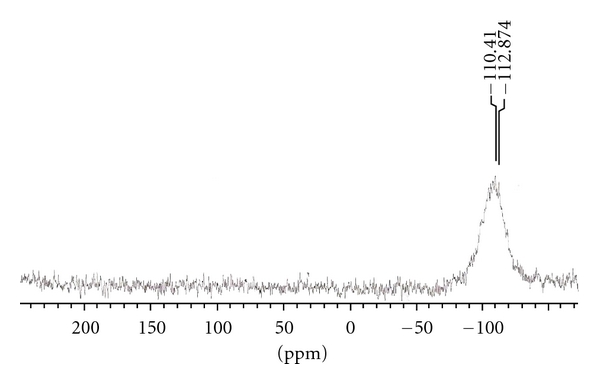

3.5. 29Si and 119Sn NMR Spectra

The value of δ 29Si and δ 119Sn indicates the coordination number of the central metal atom in the corresponding complexes [30], and generally (Figure 4), 29Si and 119Sn chemical shifts move to lower frequency with increasing coordination number of the metal atoms. The spectrum shows in each case only a sharp singlet indicating the formation of single species. 29Si and 119Sn NMR spectra of {Me2SiCl(L1)},{Me2Si(L1)2},{Me2SnCl(L1)}, and {Me2Sn(L1)2} complexes show sharp signals at δ−110.41 ppm, δ−123.35 ppm, δ−176.46 ppm, and δ−265.26 ppm, respectively, Which is indicative of pentacoordinated and hexacoordinated around the silicon and tin atom [8].

Figure 4.

29Si NMR spectrum of Si (1 : 1) metal complex of ligand (HL1).

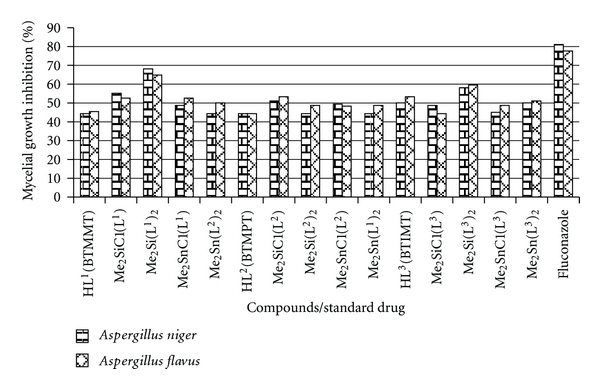

4. Biological Activities

The bactericidal and fungicidal activities of the free ligands and their metal complexes against various gram positive and gram negative bacteria and fungi are reported in Tables 5, 6, and 7.

Table 5.

In vitro antibacterial activity of the ligands and their metal complexes.

| Compounds | Zone of inhibition (mm)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | B. subtilis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | |

| HL1(BTMMT) | 16.2 | 15.6 | — | — |

| Me2SiCl(L1) | 21.6 | — | — | — |

| Me2Si(L1)2 | 20.3 | — | — | — |

| Me2SnCl(L1) | 24.6 | 22.6 | — | — |

| Me2Sn(L1)2 | — | 18.6 | — | — |

| HL2(BTMPT) | 18.8 | 18.6 | — | — |

| Me2SiCl(L2) | 23.6 | 21.3 | — | — |

| Me2Si(L2)2 | 17.3 | 15.2 | — | — |

| Me2SnCl(L2) | — | — | — | — |

| Me2Sn(L2)2 | 15.3 | 16.3 | — | — |

| HL3(BTIMT) | — | 15.9 | — | — |

| Me2SiCl(L3) | — | 20.2 | — | — |

| Me2Si(L3)2 | — | 16.2 | — | — |

| Me2SnCl(L3) | — | 16.8 | — | — |

| Me2Sn(L3)2 | — | 15.3 | — | — |

| Ciprofloxacin | 27.6 | 26 | — | — |

—: No activity.

aValues, including diameter of the well (8 mm), are means of three replicates.

Table 6.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) in μg/mL of the ligands and their metal complexes.

| Compound | S. aureus | B. subtilis |

|---|---|---|

| HL1(BTMMT) | >128 | 128 |

| Me2SiCl(L1) | 64 | Nt |

| Me2Si(L1)2 | 64 | Nt |

| Me2SnCl(L1) | 28 | 54 |

| Me2Sn(L1)2 | Nt | 64 |

| HL2(BTMPT) | Nt | 128 |

| Me2SiCl(L2) | 28 | 58 |

| Me2Si(L2)2 | 128 | >128 |

| Me2SnCl(L2) | — | — |

| Me2Sn(L2)2 | 128 | 128 |

| HL3(BTIMT) | Nt | 128 |

| Me2SiCl(L3) | Nt | 128 |

| Me2Si(L3)2 | Nt | 128 |

| Me2SnCl(L3) | Nt | 128 |

| Me2Sn(L3)2 | Nt | 128 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 5 | 5 |

Nt: Not tested.

Table 7.

In vitro antifungal activity of the ligands and their metal complexes.

| Compound | Mycelial growth inhibition (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus niger | Aspergillus flavus | |

| HL1(BTMMT) | 44.4 | 45.5 |

| Me2SiCl(L1) | 55.2 | 52.5 |

| Me2Si(L1)2 | 68.2 | 64.8 |

| Me2SnCl(L1) | 48.8 | 52.5 |

| Me2Sn(L1)2 | 44.4 | 50 |

| HL2(BTMPT) | 44.4 | 44.4 |

| Me2SiCl(L2) | 51.1 | 53.3 |

| Me2Si(L2)2 | 44.4 | 48.8 |

| Me2SnCl(L2) | 49.4 | 48.4 |

| Me2Sn(L2)2 | 44.4 | 48.8 |

| HL3(BTIMT) | 50 | 53.3 |

| Me2SiCl(L3) | 48.8 | 44.4 |

| Me2Si(L3)2 | 58.1 | 59.5 |

| Me2SnCl(L3) | 45 | 48.8 |

| Me2Sn(L3)2 | 50 | 51.1 |

| Fluconazole | 81.1 | 77.7 |

4.1. In Vitro Antibacterial Assay

The newly synthesized ligands and their metal complexes were screened for their antibacterial activities against test bacteria namely Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis (Gram positive), Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Gram negative). The activity is determined by reported Agar well diffusion method [31, 32]. All the microbial cultures were adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standards, which is visually comparable to a microbial suspension of approximately 1.5 × 108 cfu/mL. 20 mL of Mueller Hinton Agar medium was poured into each petri plate and plates were swabbed with 100 μL inocula of the test microorganisms and kept for 15 min for adsorption. Using sterile cork borer of 8 mm diameter, wells were bored into the seeded agar plates, and these were loaded with a 100 μL volume with concentration of 4.0 mg/mL of each compound reconstituted in the DMSO. All the plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hrs. Antibacterial activity of each synthetic compound was evaluated by measuring the zone of growth inhibition against the test organisms with zone reader (Hi Antibiotic zone scale). DMSO was used as a negative control, whereas Ciprofloxacin was used as positive control. This procedure was performed in three replicate plates for each organism.

4.2. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

MIC of the various compounds against bacterial strains was tested through a macrodilution tube method as recommended by NCCLS [33]. In this method, the various test concentrations of synthesized compounds were made from 128 to 0.25 μg/mL in sterile tubes nos. 1 to 10. 100 μL sterile Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) was poured in each sterile tube followed by addition of 200 μL test compound in tube 1. Twofold serial dilutions were carried out from tube 1 to the tube 10 and excess broth (100 μL) was discarded from the test tube no. 10. To each tube, 100 μL of standard inoculum (1.5 × 108 cfu/mL) was added. Ciprofloxacin was used as control. Turbidity was observed after incubating the inoculated tubes at 37°C for 24 hrs.

4.3. In Vitro Antifungal Activity

The ligands and their metal complexes were also screened for their antifungal activity against two fungi, namely, A. niger and A. flavus, the ear pathogens isolated from the patients of Kurukshetra [34], by poison food technique [35]. The moulds were grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) at 25°C for 7 days and used as inocula. The 15 mL of molten SDA (45°C) was poisoned by the addition of 100 μL volume of each compound having concentration of 4.0 mg/mL reconstituted in the DMSO, poured into a sterile petri plate and allowed it to solidify at room temperature. The solidified poisoned agar plates were inoculated at the center with fungal plugs (8 mm diameter) obtained from the colony margins and incubated at 25°C for 7 days. DMSO was used as the negative control whereas Fluconazole was used as the positive control. The experiments were performed in triplicates. Diameter of fungal colonies was measured and expressed as percent mycelial inhibition by applying the formula.

| (2) |

where dc is the average diameter of fungal colony in negative control sets and dt is the average diameter fungal colony in experimental sets.

4.4. Observations

The antibacterial data reveals that the complexes are superior compared to the free ligands. The free ligands and their metal complexes are active against Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtilis) and inactive against gram negative bacteria (Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa). Among the synthesized compounds tested compounds, Me2SnCl(L1) and Me2SiCl(L2) show more antibacterial activity that is, near to standard drug (Ciprofloxacin) (Table 5). In the series, the MIC of the compounds ranged between 28–128 μg/mL against Gram-positive bacteria. Compound Me2SnCl(L1) and Me2SiCl(L2) show highest MIC of 28 μg/mL against S. aureus (Table 6). The antifungal activity of compounds (Figure 5) shows more than 50% inhibition of mycelia growth against Aspergillus niger and A. flavus (Table 7). Thus, it can be postulated that further studies of these complexes in this direction could lead to more interesting results.

Figure 5.

Comparison of antifungal activity of compounds with commercial antibiotic.

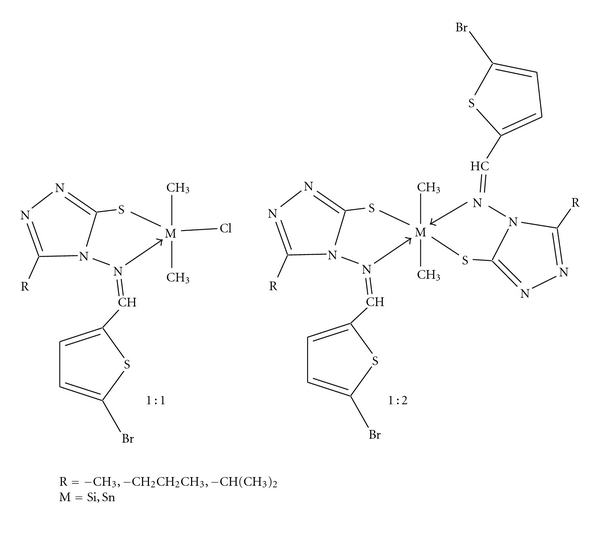

5. Conclusion

Trigonal bipyramidal and octahedral geometries have been proposed for 1 : 1 and 1 : 2 organosilicon(IV) and organotin(IV) complexes with the help of various physico-chemical studies like IR, UV, 1H, 13C, 29Si, and 119Sn NMR (Figure 6). The free ligands, and their metal complexes were screened against various fungi and bacteria to access their potential as antimicrobial agents. The antimicrobial data reveals that the complexes are superior to the free ligands and their toxicity has increased as per the increase in concentration. These compounds were found more potent inhibitor of fungal growth as compared to the bacterial culture.

Figure 6.

Proposed structures of the 1 : 1 and 1 : 2 complexes, where 1 : 1 complexes, coordination number = 5 are proposed to have trigonal bipyramidal and 1 : 2 complexes, coordination number = 6 are proposed to have octahedral geometries.

Acknowledgments

The financial assistance from UGC, New Delhi, vide Major Research Project F. no. 34-317/2008(SR), provided Project fellowship to one of the author (P. Puri), is gratefully acknowledged. The authors are also thankful to the Head, SAIF, CDRI, Lucknow and the Head, SAIF, IIT-Bombay for providing metal NMR and elemental analyses.

References

- 1.Pereyre M, Quintard JP, Rahm A. Tin in Organic Synthesis. London, UK: Butterworth; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marton D, Russo U, Stivanello D, Tagliavini G. Preparation of benzylstannanes by zinc-mediated coupling of benzyl bromides with organotin derivatives: physicochemical characterization and crystal structures. Organometallics. 1996;15(6):1645–1650. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehrotra RC, Singh A. Organometallic Chemistry: A Unified Approach. New Delhi, India: New age international; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pellerito L, Nagy L. Organotin(IV)n+ complexes formed with biologically active ligands: equilibrium and structural studies, and some biological aspects. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 2002;224(1-2):111–150. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahid K, Ali S, Shahzadi S. The chemistry, properties, and characterization of organotin(IV)complexes of 2-(N-naphthylamido)benzoic acid. Journal of Coordination Chemistry. 2009;62(17):2919–2926. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joshi KC, Pathak VN, Arya P. Synthesis of some new fluorine containing condensed thiazoles and their fungicidal activity. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 1977;41(3):543–546. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain M, Gaur S, Diwedi SC, Joshi SC, Singh RV, Bansal A. Nematicidal, insecticidal, antifertility, antifungal and antibacterial activities of salicylanilide sulphathiazole and its manganese, silicon and tin complexes. Phosphorus, Sulfur and Silicon and the Related Elements. 2004;179(8):1517–1537. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh K, Dharampla, Dhiman SS. Spectral studies and antimicrobial activities of organosilicon(IV) and organotin(IV) complexes of nitrogen and sulfur donor Schiff bases derived from 4-amino-5-mercapto-3-methyl-s-triazole. Main Group Chemistry. 2009;8(1):47–59. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sedaghat T, Shokohipour Z. Synthesis and spectroscopic studies of new organotin(IV) complexes with tridentate N- and O-donor Schiff bases. Journal of Coordination Chemistry. 2009;62(23):3837–3844. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh K, Puri P, Dharampal Synthesis and spectroscopic studies of some new organometallic chelates derived from bidentate ligands. Turkish Journal of Chemistry. 2010;34(4):499–507. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saxena C, Singh RV. Diorganosilicon(iv) complexes of fluoro-imines: synthetic, spectroscopic and biological aspects. Phosphorus, Sulfur and Silicon and Related Elements. 1994;97(1–4):17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tripathi UN, Venubabu G, Ahmad MS, Kolisetty SSR, Srivastava AK. Synthesis, spectral and antimicrobial studies of diorganotin(IV)3(2′- hydroxyphenyl)-5-(4-substituted phenyl) pyrazolinates. Applied Organometallic Chemistry. 2006;20(10):669–676. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh K, Dharampal, Parkash V. Synthesis, spectroscopic studies, and in vitro antifungal activity of organosilicon(IV) and organotin(IV) complexes of 4-amino-5-mercapto-3-methyl-S- triazole Schiff bases. Phosphorus, Sulfur and Silicon and the Related Elements. 2008;183(11):2784–2794. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiano L, Fedeli D, Moretti M, Falcioni G. DNA damage induced by organotins on trout-nucleated erythrocytes. Applied Organometallic Chemistry. 2001;15(7):575–580. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerasimchuk N, Maher T, Durham P, Domasevitch KV, Wilking J, Mokhir A. Tin(IV) cyanoximates: synthesis, characterization, and cytotoxicity. Inorganic Chemistry. 2007;46(18):7268–7284. doi: 10.1021/ic061354f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmad MS, Hussain M, Hanif M, Ali S, Mirza B. Synthesis, chemical characterization and biological screening for cytotoxicity and antitumor activity of organotin (IV) derivatives of 3,4-methylenedioxy 6-nitrophenylpropenoic acid. Molecules. 2007;12(10):2348–2363. doi: 10.3390/12102348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh K, Dharampal, Dhiman SS. Synthetic, structural and biological studies of organotin(IV) complexes of schiff bases derived from pyrrol-2-carboxaldehyde. Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society. 2010;7(1):243–250. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh K, Dharampal Synthetic, structural and biological studies of organosilicon(IV) complexes of Schiff bases derived from pyrrole-2-carboxaldehyde. Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society. 2010;75(7):917–927. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bala S, Gupta RP, Sachdeva ML, Singh A, Pujari HK. Heterocyclic systems containing bridgehead nitrogen atom: part XXXIII–syntheses of s-Triazolo[I,3,4] thiadiazine, s-Triazolo[3,4,b][I,3,4]thiadiazino[6,7-b]quinoxaline & as-Triazino [I,3,4]- thiadiazines. Indian Journal of Chemistry. 1978;16:481–483. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhaka KS, Mohan J, Chadha VK, Pujari HK. Heterocyclic systems containing bridgehead nitrogen atom: part XVI-Syntheses of s-Triazolo[3,4-b][1,3,4] thiadiazines and related heterocycles. Indian Journal of Chemistry. 1974;12:p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh G, Singh PA, Singh K, Singh DP, Handa RN, Dubey SN. Synthesis and structural studies of some bivalent metal complexes with bidentate Schiff base ligands. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences India. 2002;72(A-2):87–95. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avaji PG, Patil SA, Badami PS. Synthesis, spectral, thermal, solid state d.c. electrical conductivity and biological studies of Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) complexes with 3-substituted-4-amino (indole-3-aldehydo)-5-mercapto-1,2,4-triazole Schiff bases. Journal of Coordination Chemistry. 2008;61(12):1884–1896. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinha BK, Singh R, Srivastava JP. Substituted 1,2,4-triazoles as complexing ligands-I Ni(II), Co(II), Cu(II), Zn(II), Pd(II), Cd(II) and Pb(II) complexes with 4-amino-3,5-dimercapto-1,2,4-triazole. Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry. 1977;39(10):1797–1801. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh K, Singh RV, Tandon JP. Synthesis and structural features of organo Si(IV) imine complexes. Polyhedron. 1988;7(2):151–154. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belwal S, Singh RV. Bioactive versatile azomethine complexes of organotin(IV) and organosilicon(IV) Applied Organometallic Chemistry. 1998;12(1):39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh K, Singh DP, Barwa MS, Tyagi P, Mirza Y. Antibacterial Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes of Schiff bases derived from fluorobenzaldehyde and triazoles. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;21(5):557–562. doi: 10.1080/14756360600642131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suresh, Srinivas P, Suresh T, Revanasiddappa M, Khasim S. Synthetic, spectral and thermal studies of tin(IV) complexes of 1, 5-benzodiazepines. E-Journal of Chemistry. 2008;5(3):627–633. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nath M, Goyal S, Goyal S. Synthesis, spectral and biological studies of organosilicon(IV) complexes of Schiff bases derived from amino acids. Synthesis and Reactivity in Inorganic and Metal-Organic Chemistry. 2000;30(9):1794–1804. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaudhary A, Singh RV. Studies on biologically potent tetraazamacrocyclic complexes of bivalent tin. Phosphorus, Sulfur and Silicon and the Related Elements. 2003;178(3):615–626. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pellei M, Lobbia GG, Ricciutelli M, Santini C. Synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of new organotin(IV) complexes with bis(3,5-dimethylpyrazol-1-yl)dithioacetate. Journal of Coordination Chemistry. 2005;58(5):409–420. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmad I, Beg AZ. Antimicrobial and phytochemical studies on 45 Indian medicinal plants against multi-drug resistant human pathogens. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2001;74(2):113–123. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00335-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andrews JM. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2001;48(1):5–16. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.suppl_1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.NCCLS. Method for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, Approved Standards. 5th edition. Villanova, Pa, USA: National Committee for Clinical Standards; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aneja KR, Sharma C, Joshi R. Fungal infection of the ear: a common problem in the north eastern part of Haryana. International Journal of Otorhinolaryngology. 2010;74(6):604–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al-Burtamani SKS, Fatope MO, Marwah RG, Onifade AK, Al-Saidi SH. Chemical composition, antibacterial and antifungal activities of the essential oil of Haplophyllum tuberculatum from Oman. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2005;96(1-2):107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]