Abstract

It was predicted that because of their abstract nature, values will have greater impact on how individuals plan their distant future than their near future. Experiments 1 and 2 found that values better predict behavioral intentions for distant future situations than near future situations. Experiment 3 found that whereas high-level values predict behavioral intentions for more distant future situations, low-level feasibility considerations predict behavioral intentions for more proximate situation. Finally, Experiment 4 found that the temporal changes in the relationship between values and behavioral intentions depended on how the behavior was construed. Higher correspondence is found when behaviors are construed on a higher level and when behavior is planned for the more distant future than when the same behavior is construed on a lower level or is planned for the more proximal future. The implications of these findings for self-consistency and value conflicts are discussed.

Keywords: Construal, Values, Construal level theory, Time perspective, Behavioral intentions

Introduction

People often think of themselves and their actions in terms of abstract values, ideologies, and moral principles. For example, one might characterize herself as a person who values friendship, security, or protection of the environment. Similarly, one might think of an action, such as donating money for the poor, as promoting social justice. In addition, people often try to live up to their values. For instance, an individual who values preserving the environment might be quite receptive to the idea of cleaning up a highway or donating money to restore the Everglades. Indeed, the value literature suggests that people attach great importance to their values as behavioral guides and see them as central to their self-identity (e.g., Feather, 1990; Maio & Olson, 1998; Rokeach, 1973; Schwartz, 1992; Seligman & Katz, 1996; Verplanken & Holland, 2002).

The relationships found between values and behavior have been highly variable in magnitude. Whereas some research documents high correlations between values and intentional behaviors (e.g., Bardi & Schwartz, 2003; Sagiv & Schwartz, 1995), others have found values to be poor predictors of behavior (e.g., Kristiansen & Hotte, 1996). These findings parallel a considerable amount of research showing that, like values, people's attitudes and personality traits sometimes serve as fair predictors of their behavior, but at other times fail to do so (Ajzen, 1987; Mischel,1968, 1984; Mischel & Shoda, 1995). The question, then, is what determines the relationship between values and intentions. Below, we review past research that bears on this question, and then propose a new perspective that is based on construal level theory (Liberman, Trope, & Stephan, 2007; Trope & Liberman, 2003). We argue that, since perceptions of distant future situations highlight more abstract, high-level features than near future situations, they are more influenced by high-level constructs such as values. Consequently, people are more likely to use their values in construing and forming behavior intentions with respect to distant future situations than near future situations.

Values as guides

Compared to research on attitude–behavior and trait–behavior relationships, the amount of research on value–behavior relationship is relatively small. Nevertheless, this research has identified several factors that affect the correspondence between values and behavior. Feather (1995) found that the valence of actions and their possible outcomes moderates the relationship between values and choices. The more one perceives an alternative as attractive, the stronger the relation between the values and the selected behavior. Kristiansen and Hotte (1996) suggested that the level of moral reasoning moderates the relation between values and behavior, such that relative to people in a lower stage of moral development, people who have reached a higher stage of moral development are more likely to act in accord with their internalized values. Centrality to the self is another factor that has been suggested as a moderator of the value–behavior relation. For example, it was found that activating a value resulted in value–congruent behavior if the value was central to the self-concept (Verplanken & Holland, 2002), and that people with more clearly articulated self-concepts show stronger value–behavior relations (Kristiansen & Hotte, 1996). Action identification theory (Vallacher & Wegner, 1987) proposes that values predict behaviors in situations that are construed in relevant terms. For example, the value of honesty and moral conduct will predict cheating in an exam only if the potential cheater construes this action in terms that are relevant to morality, but not if she thinks of it as “comparing answers” or “being social.”

Interestingly, research on symbolic politics (e.g., Kinder & Sears, 1981; Sears, Lau, Tyler, & Allen, 1980, see also Eagly & Chaiken, 1993) suggests that political attitudes and behavioral intentions (i.e., voting) are predicted by values. In fact, this research has shown that political attitudes and intentions are better predicted by symbolic beliefs that reflect abstract values such as fairness and equality than by self-interest. For example, Kinder and Sears (1981) found that the intention to vote for an African-American mayor was predicted by abstract moral values (e.g., affirmative action) but not by self-interest considerations (i.e., perceived racial threat to whites' lives). These findings suggest that political attitudes and voting intentions are construed in terms of general and abstract societal issues and therefore are more compatible with abstract, general values than with tangible, everyday life concerns.

The role of time perspective

From the perspective of construal level theory (CLT, Liberman et al., 2007; Trope & Liberman, 2003), values will predict behavioral intentions to the extent that the situation at hand is construed in terms of those values. A defining characteristic of values, one that distinguishes them from attitudes and goals, is that they apply to a wide range of behaviors and situations (e.g., Feather, 1995; Rohan, 2000; Rokeach, 1973; Schwartz, 1992; Schwartz & Bilsky, 1987; Verplanken & Holland, 2002). For example, attaching importance to the value of security implies diverse behaviors such as striving for safety at home, at work, while driving, at the national level, etc. Because values impart a common meaning to many different behaviors and situations, they are abstract, high-level mental constructs.

According to CLT, individuals form higher-level, abstract mental construals of events that are expected in the distant future. Whereas construals of near future events are rich in details, some of which are contextual, incidental or peripheral, construals of distant future events include more central features of the event and thus are more abstract and schematic. For example, getting a new job in the relatively distant future is more likely to be represented as an opportunity for advancement, whereas getting this job in the more immediate future is likely to be represented in terms of the preparations and selection procedures one would have to undergo. Past research on temporal construal has shown that when an event is expected in the more distant future (e.g., “a month from now” vs. “tomorrow”), it is more likely to be classified, described, and recalled in terms of (a) superordinate desirability features vs. subordinate feasibility features, (b) fewer, broader categories, and (c) general prototypes (Liberman, Sagristano, & Trope, 2002; Liberman & Trope, 1998; Nussbaum, Trope, & Liberman, 2003). For example, participants were more likely to describe daily activities (e.g., “watching TV”) in terms of superordinate end-states (“being entertained”) rather than in terms of subordinate means (“flipping channels”) when the activities were expected in the distant future (Liberman & Trope, 1998).

CLT further suggests that the temporal shifts in construal affect individuals' preferences. Specifically, as temporal distance increases, high-level construals of the choices become more influential, whereas low-level construals become less influential. Supporting this analysis, past research has found that superordinate aspects of future activities were more influential in making choices for the distant future, whereas subordinate aspects of these activities were more influential in making choices for the near future. For example, temporal distance increased the influence of superordinate, desirability aspects (the value of an action's end-state) and decreased the influence of subordinate, feasibility aspects (the means for reaching the end-state) in choice of future activities (Liberman & Trope, 1998; Sagristano, Liberman, & Trope, 2002).

Because of their high-level nature, values are more likely to be activated when considering more distant future situations. For example, taking a medical check-up in the relatively distant future is more likely to be represented as an opportunity to improve one's health, whereas taking the medical check-up in the immediate future is more likely to be represented in terms of the discomfort it involves or the time it takes. Thus, the value individuals attach to health is more likely to guide one's decision to sign up for a distant future medical check-up than a near future medical check-up. The same should hold for any value, not only those that are socially desirable or that involve an immediate sacrifice. For example, individuals' hedonic values are more likely to be expressed in the leisure activities they plan for a distant future weekend than for a near future weekend. In general, we expect values to better predict intentions for distant than immediate behavior.

This prediction is consistent with Ajzen and Fishbein's (1977) compatibility principle, which states that attitudes predict behavior to the extent that the two are at comparable levels of specificity. Fishbein and Ajzen (1974) proposed that behaviors could be made more comparable to general attitudes by presenting behaviors more abstractly. Their research has shown that general attitudes (e.g., attitude toward religion) better predict behavioral measures that match the attitude in abstraction (e.g., attending church vs. attending service on a specific date). Eliminating low-level incidental features (e.g., a specific date of service) and retaining central, essential features of the behavior achieves an abstract representation of behavior.

Note, however, that the compatibility principle assumes that the objective properties of behavior determine its level of specificity. In contrast, CLT proposes that, depending on temporal perspective, the same behavior may be construed abstractly or concretely, which, in turn, determines whether the intention to engage in that behavior will be predicted by one's general attitudes and values. That is, the same behavior is likely to be construed at a higher, decontextualized level when expected in the more distant future. Therefore, the intention to carry out the behavior is likely to be better predicted by one's values.

The present research

Four experiments were designed to test the time-dependent changes in the relationship between values and behavioral intentions. Experiments 1 and 2 assess participants' values and examine the extent to which they predict behavioral intentions, assessed in a separate session, regarding near future vs. distant future activities. It is predicted that values would better predict temporally distant than temporally near behavioral intentions. Experiment 3 further tests the prediction that near future intentions are not simply less predictable, but rather, they are predictable from value-unrelated, low-level aspects of the situation. This is done by measuring values as well as manipulating the feasibility of performing the behavior, which is a low-level feature of the decision situation. Finally, Experiment 4 examines the construal mechanism that presumably underlies temporal shifts in the relationship between values and behavioral intentions. This is achieved by experimentally inducing a high- or low-level of construal of the future behaviors, in addition to a control condition in which level of construal is not induced, but is allowed to vary with temporal distance. It is predicted that like greater temporal distance, more abstract construals of future behaviors would increase value-consistent intentions. Therefore, the effect of temporal distance on the correspondence between values and intentions would be weaker when a high- or low-level construal is induced, compared to a control condition where level of construal of the behavior is free to vary with temporal distance.

Experiment 1: value–behavioral intention correspondence

We predicted that, since temporally distant situations are more likely to be construed in terms of one's values, those values are more likely to guide behavioral choices for those situations. People's values should therefore predict their behavioral intentions better for distant future situations than for near future situations. To test this prediction, we first measured participants' value priorities, and then, at a later experimental session, measured their likelihood of performing value-relevant behaviors (e.g., participate in a family reunion), either in the near future or in the distant future. We predicted that the correlations between values and the corresponding behavioral intentions would be higher in the distant future than in the near future.

Methods

Participants

Seventy-one New York University undergraduate students (51 women), ages 18–29, participated in the experiment for partial fulfillment of a course requirement. They were randomly assigned to one of the two temporal distance conditions.

Procedure

We measured participants' endorsement ratings of 25 broad values (e.g., respect for tradition, self-discipline) in a mass testing session at the beginning of the semester. For each of the values, participants reported their level of support on a scale ranging from 1 (low support) to 7 (complete support). These items were adapted from Schwartz (1992) value questionnaire, which originally contained 56 value items1. We selected items that corresponded to the behaviors we presented to participants.

At a later date, participants read eleven vignettes of hypothetical situations typical to everyday student life (e.g., attending a family reunion, preparing a guest list for a friend's party), taking place either that week (near future), or sometime in a few months (distant future). Each vignette presented a potential behavior that was consistent with one of the values measured in the pre-testing session. Each description provided contextual information in which the behavior was embedded. This information described the setting for the behavior, such as the precise timing, people involved, visual details, weather, etc. Such information allows intentions to be formed on the basis of factors other than relevant values. For example, the description of a family reunion (consistent with the value of respect for tradition) read as follows, with the distant future version in parentheses:

Imagine that you come from a close-knit family that has a tradition of holding a big family “reunion” or get-together every five years. You find out from your parents that this coming weekend (on a weekend during this coming February), a reunion is being held at your Aunt's place in Virginia. You could probably make it down there for that weekend, and you would be able to see some old friends and relatives. Transportation is arranged for you already, and you would meet up with everyone when you got down there.

After reading each vignette, participants provided their intention to perform the proposed behavior on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all likely) to 9 (very likely).

Results

The data were analyzed using multilevel linear models (see Kenny, Kashy, & Bolger, 1998), using HLM 5.04 software, an analysis that allowed us to collapse all 11 value–behavioral intention pairs in aggregate for each subject. In the first level of this model, regression equations for each vignette predicted behavioral intention from values. The second level of the model first combined the 11 value–behavior pairs into one measure of value-intention correspondence per subject and then tested the effect of temporal distance on this measure.

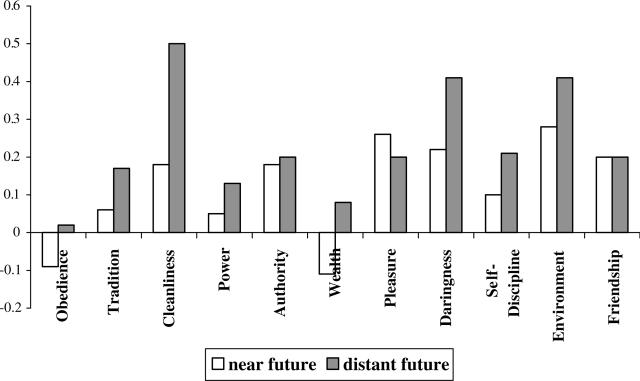

Fig. 1 presents the simple correlations between value and behavioral intention for each vignette. Overall, the value measures significantly predicted the corresponding behavioral intention, b = .27, SE = .08, t(69) = 3.35, p < .01. More importantly, there was greater correspondence between value and intention in the distant future (b = .53) than in the near future (b = .27), difference b = .28, SE = .10, t(69) = 2.83, p < .01. Temporal distance alone did not impact intentions, b = .04, SE = .07, t(69) = 0.54, p > .05, indicating that individuals did not differ in their general likelihood to form intentions across time condition. These results provide initial evidence that the correspondence between values and behavioral intentions depends on temporal distance from the behavior under consideration. Values better predicted distant future behavioral intentions than near future behavioral intentions, suggesting that values guide behavioral choices for the distant future more than for the near future.

Fig. 1.

Correlations between values and corresponding behavioral intentions as a function of temporal distance (Experiment 1).

Experiment 2: value–behavioral intention correspondence: A replication and extension

The aim of Experiment 2 was to extend the results of Experiment 1 by presenting participants with several behaviors (rather than a single behavior) for each value. As before, we expected that values, due to their abstract high-level nature, would better predict behavioral intentions for the distant future than for the near future. To test this prediction, participants imagined various behaviors (e.g., rest as much as I can) and indicated the likelihood of performing each behavior either in the near future or in the distant future. The behaviors were taken from Bardi and Schwartz (2003), and were designed to correspond to the values in Schwartz's (1992) value questionnaire, which our participants completed in an earlier session.

Methods

Participants

One-hundred and one Tel-Aviv University psychology undergraduates (80 women) participated in the experiment for course credit. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two temporal distance conditions.

Procedure

Participants were first asked to imagine themselves and their lives either next week (near future condition), or a year from now (distant future condition). They then rated the likelihood of performing each of 30 behaviors next week (a year from now) on a scale ranging from 1 (low) to 5 (high). Behaviors were adopted from Bardi and Schwartz's (2003) questionnaire. We chose from the original set of behaviors three behaviors for each value. For example, the behavior “use environmentally friendly products” expresses the value “universalism” and the behavior “examine the ideas behind rules and regulations before obeying them” expresses the value “self-direction”. Next, participants answered questionnaires unrelated to the experiment for 10 min, and then completed Schwartz's (1992) value questionnaire. Unlike in Experiment 1, in the current experiment we used the original value questionnaire by Schwartz (1992). This questionnaire lists 56 value items, each followed by a short definition in parentheses. Participants rated the extent to which each value was a guiding principle in their lives on a 9-point scale. −1 was labeled “opposed to my principles,” 0 was labeled “not important” and 7 was labeled “of supreme importance.” Following Schwartz's (1992) procedure, participants were instructed to first read the entire questionnaire, select and rate the values most and least important to them, and only then rate all remaining values.

Results and discussion

We averaged the ratings of items from Schwartz's (1992) values questionnaire that pertain to the 10 value clusters (reliability of the 10 value clusters ranged from Cronbach α = .47 to Cronbach α = .81). In order to examine the correspondence between each behavior and the relevant value, we used the same hierarchical linear analysis as in Experiment 1. The first level of analysis predicted behavioral intentions from values with 10 values for each participant and three behavioral intentions for each value. The second level of analysis tested the effects of temporal distance on value–behavioral intention correspondence. The analysis showed, as can be seen in Fig. 2, that values better predicted distant future behavioral intentions (b = .61) than near future behavioral intentions (b = .36), difference b = .22, SE = .09, t(99) = 2.51, p < .05.

Fig. 2.

Correlations between values and corresponding behavioral intentions as a function of temporal distance (Experiment 2).

The results of this experiment, together with the results of Experiment 1, demonstrate that temporal distance from an event moderates the relationship between one's values and behavioral intentions, so that value-intention correspondence was greater for distant future situations than near future situations. Behavioral intentions for the distant future seem to be based on a representation of the situation that is structured around a central value one holds. In contrast, behavioral choices for the near future seem to be influenced by a more diverse, and perhaps less structured, set of considerations that include many specific and peripheral aspects of the situation. The impact of the value that is pertinent to the choice is therefore naturally diminished in the temporally proximal perspective compared to the temporally distal perspective. In other words, people are better able to express their cherished values in planning the distant future than in planning the near future.

Experiment 3: Predicting behavioral intentions from values and feasibility considerations

Experiments 1 and 2 demonstrate that people's values predict their behavioral intentions for the distant future more than for the near future. However, these experiments do not examine what determines people's behavioral intentions for near future situations. Based on CLT, we suggest that behavioral intentions for the near future are influenced by low-level aspects of the event, such as feasibility aspects, rather than by high-level aspects, such as one's values. Experiment 3 was designed to test this prediction. After completing a paid experiment, participants were asked to volunteer for another experiment, which did not offer either payment or course credit. Participants were told that the experiment would take place either in the near future or in the distant future. In the low feasibility condition, the experiment was said to take place early in the morning, which pretesting showed was an inconvenient time for most students, whereas in the high feasibility condition, it was said to take place in the afternoon, which pretesting showed was a convenient time for most students. Participants indicated the amount of time they would be willing to contribute to participation in an experiment. We predicted that participant's benevolence values would better predict the amount of time they would be willing to contribute in a temporally distant experiment than in a temporally near experiment. We also expected that feasibility considerations would better predict the amount of time participants would be willing to contribute in a temporally near experiment than in a temporally distant experiment.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 82 undergraduate students from Ben Gurion University (57 women) who took part in a 45 min experimental session and received 30 shekels (about $8) for participation. The experiment was conducted in groups of 5–8 participants. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two temporal distance conditions and to one of the two feasibility conditions.

Procedure

Participants first completed a paid, 45 min experimental session. This experiment was conducted at the BGU School of Business, and included various tasks such as Schwartz's (1992) value scale (administered at the beginning of the experimental session), surveys about participants' courses and school life in general (e.g., academic, leisure time, emotional reactions), and a perception task. All these tasks were completed on desktop computers. Upon completing the experimental session, participants were paid and debriefed. They were then approached by the experimenter who told them that one of her friends, a psychology graduate student, was looking for student participants for her experiment. Participants were handed a request that was supposedly written by the graduate student and read as follows:

“Hello, my name is Yael, and I'm a Psychology graduate student. To complete my dissertation, I need many students to participate in my experiments. It would really help me if you could participate in one of my experiments! Some of my experiments take a few minutes, whereas others may take up to an hour. The more time you contribute, the more helpful it would be. Unfortunately, I cannot pay or give credit for participation. The experiments will take place in the next few days (in a few months, during the second semester) in the afternoon [early in the morning, between 7AM and 9AM]”.

Four versions varied, between participants, the temporal distance of the expected experiment (in the next few days versus in a few months), and the feasibility level (in the afternoon versus early in the morning between 7AM and 9AM).2 Participants were asked to list their name and email if they wished to participate in one of the student's experiments, and the number of minutes they would be willing to contribute.

Results and discussion

Only participants who indicated their name, email, and amount of time for participation were included in the analysis. We first averaged, for each participant, the five items from the value scale referring to benevolence value (Cronbach α = .70) and then identified those who were below versus above the median (Median = 5). We then conducted a 2 (temporal distance: near future vs. distant future) by 2 (benevolence: low vs. high) by 2 (feasibility: low vs. high) ANOVA on the number of minutes participants were willing to contribute. The analysis yielded a temporal distance by benevolence interaction, F(1, 74) = 3.95, p < .05. This indicates, as can be seen in Table 1, that when the experiment was expected to take place in the distant future, those high in benevolence were willing to contribute more time to an experiment (M = 43.89, SD = 15.00) than those low in benevolence (M = 31.59, SD = 13.66), F(1, 74) = 7.34, p < .01. However, when the experiment was expected to take place in the near future, there was no difference in contribution time between those high in benevolence (M = 30.26, SD = 14.95) and those low in benevolence (M = 34.35, SD = 22.33), F <1, ns.

Table 1.

Amount of time intended to volunteer in an experiment as a function of temporal distance, benevolence and feasibility considerations (Experiment 3)

| Feasibility | Benevolence |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Total | |

| Low | |||

| Near future | 25.45 (14.40) | 28.33 (16.58) | 26.75 (15.07) |

| Distant future | 30.00 (16.73) | 49.09 (15.14) | 40.83 (18.49) |

| High | |||

| Near future | 42.50 (25.63) | 32.00 (13.98) | 37.73 (21.37) |

| Distant future | 32.19 (12.91) | 35.71 (11.34) | 33.26 (12.30) |

| Total | |||

| Near future | 34.35 (22.33) | 30.26 (14.95) | |

| Distant future | 31.59 (13.66) | 43.89 (15.00) | |

In addition, the analysis yielded a temporal distance by feasibility interaction, F(1,74) = 4.39, p < .05. This indicates, as can be seen in Table 1, that when the experiment was expected to take place in the near future, participants were willing to contribute more time to an experiment at a convenient time (M = 37.73, SD = 21.37) than an inconvenient time (M = 26.75, SD = 15.07), F(1, 79) = 4.33, p < .05. However, when the experiment was expected to take place in the distant future, time contribution was not significantly affected by whether the timing of the experiment was convenient (M = 33.26, SD = 12.30) or inconvenient (M = 40.83, SD = 18.49), F(1, 79) = 1.98, p > .05. None of the other interactions or main effects were significant. Thus, whereas values influenced participants' intentions to contribute time in the distant future and not in the near future, feasibility considerations influenced participants' intention to contribute time in the near future but not in the distant future.

The findings of this experiment extend those of Experiments 1 and 2 in two important ways. First, they demonstrate that values better predict behavioral intentions for the more distant future, not only when the behavior is hypothetical, but also when it is actual. Second, they show that near future behavioral intentions are not simply unpredictable, but are rather predicted by low-level factors.

Note that these findings also address a possible claim that the results reflect a differential amount of knowledge- namely, that participants had more knowledge regarding the near future than the distant future. Obviously, it was not a lack of knowledge that prevented participants from taking into account the inconvenience of the time of the experiment. Students knew that the early morning is not convenient (as our pretesting showed), but nevertheless gave this consideration little weight and, instead, were guided by their values in planning behaviors for the distant future (see Liberman & Trope, 1998, for related evidence regarding the weight of feasibility in future decisions). Thus, whereas high-level values determined participants' intentions for a temporally distant situation, low-level, feasibility considerations determined participants' intentions for a temporally near situation. Experiment 4 aimed to more directly test the role of construal in determining the effect of temporal distance on the correspondence between values and behavioral intentions.

Experiment 4: The effect of manipulated level of construal on value–behavioral intention correspondence

Experiments 1–3 show that people are more likely to express their values in their behavioral intentions for more temporally distant situations. Experiment 3 additionally shows that temporally more proximal behavioral intentions are more likely to be determined by feasibility considerations. The present experiment was designed to further examine the construal mechanism that is assumed to underlie temporal changes in value–behavioral intention correspondence by experimentally inducing a high or low level of construal. More specifically, participants were instructed to imagine behaviors in terms of their essential, high-level components, or in terms of their contextual, low-level components. There was also a control group that did not get any instructions on how to construe the behaviors. We predicted that more abstract construals of behaviors, relative to a concrete construal, would increase value-consistent intentions. We also predicted that greater temporal distance would increase value-consistent intentions, as was found in Experiments 1 through 3. Moreover, we predicted that the induced construal level of behaviors would moderate the effect of time on the correlations between values and intentions. That is, the effect of temporal distance on value-consistent intentions would materialize when construal is not induced (i.e., control group) but will be weaker when either a low-level construal or a high-level construal is induced.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 158 New York University undergraduate students (110 women), who took part in the experiment for partial fulfillment of a course requirement. They were randomly assigned to one of the two temporal distance conditions and to one of the three construal level conditions.

Procedure

Similarly to Experiment 1, we measured participants' endorsement of eleven values in a mass testing session at the beginning of the semester. These measures consisted of broad values (e.g., wealth, daringness, and respect for tradition) and participants reported the extent to which they support each value on a scale ranging from 1 (low support) to 7 (complete support).

In a later session, participants read eleven vignettes of hypothetical situations related to student life, identical to those we used in Experiment 1. Each vignette presented a potential behavior that was consistent with one of the values measured in the pre-testing session and that was described as taking place either that week (near future), or sometime in a few months (distant future).

Upon reading each vignette, participants in the two experimental conditions were given instructions serving as our construal manipulation. In both conditions, participants were asked to imagine the event for a minute or two and then write a description of this image in a few sentences. The instructions were as follows:

Abstract construal

Please take a minute or two now to think about the importance and meaning of this event, including the implications for your goals, its relationship to your self-identity, as well as the meaning of the event to you and the broad consequences of this event. Use the space below to write a description of these things.

Concrete construal

Please take a minute or two now to imagine vividly how this event will occur. Think fully about the concrete details of this event, such as what things you will experience, what you will see, hear, and feel, and how you will feel and behave during this event. Use the space below to write a description of these things.

In the control condition, participants read the vignettes without any additional instructions. After reading each vignette, participants provided their intention to perform the proposed behavior on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all likely) to 9 (very likely).

Results and discussion

In order to test the effects of temporal distance and mental construal on value-intention correspondence we used hierarchical linear modeling, as in Experiments 1 and 2. Behavioral intention served as the outcome variable for the first level of our model. The predictor at this level was the value measure for the given vignette. The second level of the model predicted the regression slope of our first level equation from temporal distance, construal level, as well as the temporal distance by construal level interaction.

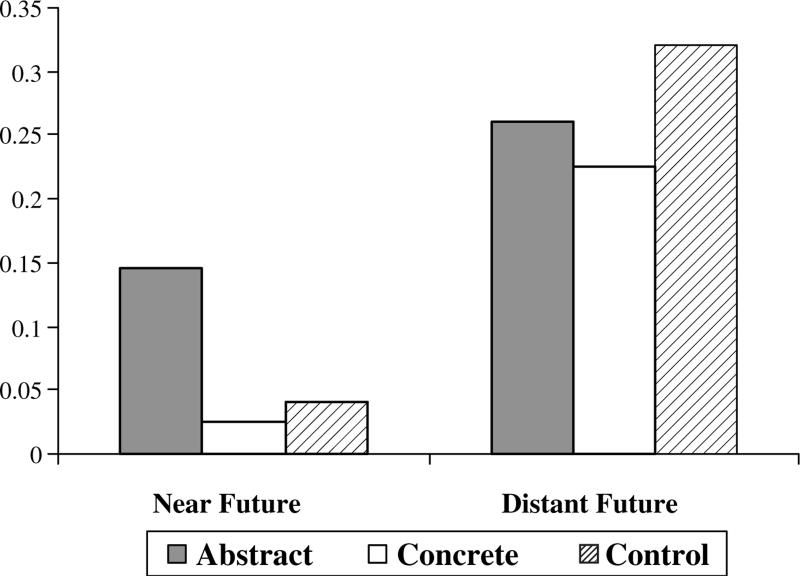

Results show that temporal distance had a positive effect on value-intention correspondence, b = .20, SE = .03, t(156) = 7.49, p < .01, indicating that values predicted intentions better in the distant future (r = .27) than in the near future (r = .07). This finding is consistent with the results of the previous three experiments. In addition, the value by temporal distance by construal condition (control vs. experimental) interaction term yielded a significant positive weight, b = .06, SE = .03, t(156) = 2.04, p < .05. This indicates, as can be seen in Fig. 3, that temporal distance had a greater effect on value-intention correspondence in the control condition (b = .28), than in our manipulated-construal conditions (b = .16).

Fig. 3.

Correlations between values and behavioral intentions as a function of temporal distance and construal level (Experiment 4).

Looking at the difference between concrete and abstract construals as a function of time (without the control group), the analysis yielded a main effect for construal on value-intention correspondence, b = .12, SE = .04, t(108) = 2.74, p < .01, indicating that values better predicted intentions when behaviors were construed on a high level (r = .22) than when behaviors were construed on a low level (r = .11). In addition, the temporal distance by construal (concrete vs. abstract) interaction term was found to be negative, b = .09, SE = .05, t(108) = 1.95, p = .05, indicating that the construal effect on the value-intention correspondence was stronger in the near than in the distant future.

Manipulating both temporal distance and construal level in this experiment allowed us to examine the relationship between temporal distance effects and construal level effects on value-intention correspondence. Results show that the difference in value-intention correspondence between distant-future and near-future conditions was more pronounced for participants in the control groups than for participants in either the abstract or concrete construal conditions. Moreover, construing a behavior on a higher level increased the correspondence between the intention to perform the behavior and the value expressed by that behavior. Thus, an abstract construal had an effect similar to that of temporal distancing.

These findings demonstrate that temporal distance has a greater impact on value-intention correspondence when level of mental representation is not constrained. When construal level was controlled for through our abstract vs. concrete construal manipulation, the effects of temporal distance on value-intention correspondence were diminished.

General discussion

The present research addresses a fundamental issue in social psychology, namely, the relationship between individuals' values and their behavioral intentions (see Eagly & Chaiken, 1993, for review). Using the framework of construal level theory (CLT; Liberman et al., 2007; Trope & Liberman, 2003), we argued that people form higher level, more abstract representations of temporally distant events than temporally proximal events. Because values are abstract, de-contextualized mental constructs, they are more likely to be applied to more distant future situations and guide behavioral intentions for those situations. We therefore expected that values would better predict distant future intentions than near future intentions. The latter more closely resemble actual, concrete behavior.

Consistent with this prediction Experiments 1 and 2 found that participants' intentions to perform behaviors in the distant future correlated more highly with previously measured values than did near future intentions. Additionally, Experiment 3 found that, whereas values better predicted intentions for distant future behaviors, low-level feasibility considerations better predicted intentions for near future behaviors. Experiment 4 extended these findings by examining the construal mechanism that is assumed to underlie the effect of temporal distance on value–behavioral intentions correspondence. This experiment manipulated level of construal directly and independently of temporal distance by instructing participants to form either concrete or abstract construals of the situation. As expected, the effect of level of construal on the value-intention correspondence was similar to that of temporal distance. That is, participants' values better predicted their intentions when participants formed abstract construal of the situation than when they formed concrete construal of the behavior. Moreover, temporal distance effects on value-intention correspondence were attenuated when a concrete or abstract construal was induced compared to when construal level was free to vary.

Together, these findings demonstrate that individuals are more likely to construe situations in terms of their values, and are actually more likely to form intentions that are consistent with their values when these intentions pertain to distant future situations versus near future situations. Moreover, the present results suggest that temporal shifts in level of construal are crucial for the temporal shift in the consistency of individuals' intentions and values. It has been argued that people tend to over attribute behavior to personal dispositions (see, e.g., Gilbert & Malone, 1995; Ross & Nisbett, 1991). The present findings suggest that people's intuitions are not always wrong. Although people's values are weak determinants of their immediate behavior intentions, those values are important determinants of their more distant behavior intentions. To the extent that people pre-commit themselves and make irreversible choices, people's basic values might guide not only behavioral intentions, but also actual behavior.

Beyond the question of values as predictors of behavioral intentions, the present findings have more general implications for self-consistency and value conflicts, which we discuss below.

Self-consistency

One implication of the present research is that intentions for the more distant future would show greater cross-situational consistency than intentions for the near future. The responses to the more proximal requests are likely to be more variable and depend on specific aspects of the style and content of the requests. Values are important aspects of individuals' self-identity (e.g., Kristiansen & Hotte, 1996; Rokeach, 1973), but the present findings suggest that individuals are more likely to express this aspect of their self-identity in behavioral intentions for the relatively distant future. For the immediate future, individuals are more likely to be influenced by specific contextual factors that are peripheral or unrelated to their self-identity. Individual differences driven by self-identity are therefore likely to emerge in intentions for the distant future. The behavioral intentions of different individuals are more likely to converge and appear more similar in what they intend to do as they get closer to enactment.

Recent research by Nussbaum et al. (2003) suggests that this temporal asymmetry in self-consistency is reflected in people's predictions of others' behavior. This research shows that people expect others to express their personal dispositions (general attitudes, traits) and act consistently across different situations in the distant future more than in the near future. Nussbaum et al. viewed these finding as evidence for “creeping dispositionism”—a tendency to see others' behavior as increasingly more reflective of their underlying dispositions as temporal distance from the behavior increases. It is as if people expect others to express their true selves in what they will do in the future but not in the near future. Correspondingly, the results of the current research suggest that people may also view themselves in terms of “what is really important to me in life” only when they think of themselves in a distant, abstract way. When they think of their actions from a proximal perspective, their “true” self may lose its clarity to pragmatic, situational constrains (e.g., money, time). It is ironic, then, that in order to reveal core aspects of their self identity, people have to adopt a more distant, perspective of themselves rather than focus on and closely examine their behavior (see Wakslak, Nussbaum, Liberman, & Trope, 2008).

Value conflicts

Whereas the current research examined behavioral intentions that related to one value in particular, in many situations, different values may be applicable to the same behavioral choice (Feather, 1995; Sagiv & Schwartz, 2000; Tetlock, 1986). For example, the decision whether to help a fellow student rather than work on one's own assignment may pit altruism and achievement values against one another. Past research has shown that individuals resolve conflicts between values in favor of the value that is deemed more central to the behavior. For example, Tetlock (1986) found that, the greater the centrality participants assigned to personal prosperity relative to social equality, the more they opposed higher taxes to assist the poor. From the perspective of CLT, central values constitute a high-level construal of action, while subordinate, peripheral values constitute a low-level construal of action. More central, superordinate values are, therefore, likely to be activated when considering psychologically distant situations, and to guide choice for those situations. As one gets closer to a situation, choices are increasingly more likely to be based on secondary, subordinate values.

Initial support for this idea comes from research by Eyal, Liberman, Sagristano, and Trope (2008). This research found that when a situation is related to different values, the individual's central values are more likely to guide choice from a psychologically distant than proximal perspective compared to individuals' secondary values. For example, individuals to whom altruism was subordinate to achievement were more likely to refuse to help a fellow student in the distant future than the near future, whereas individuals to whom achievement was subordinate to altruism were more likely to help a fellow student in the distant future than the near future. These findings extend the findings of the present research by showing that secondary values, which are nonetheless part of an individual's self identity, may mask the influence of primary values on near future intentions in the same manner as specific, situational factors that are unrelated to people's values (contextual “noise”).

Conclusion

The present research demonstrates that personal values better predict individuals' mental construal and intentions for distant future behaviors than near future behaviors. Personal values seem to provide a general interpretive frame and behavioral guide for the relatively distant future. The immediate future is construed in terms of more specific, situational aspects that are unrelated to one's general values. For example, a person who values adventures and risk-taking may constantly plan activities that express this value (e.g., bungee jump) in the future, but rarely actually engage in those things, due to incidental constraints. Thus, while values may guide people's plans, low-level, local, and sometime incidental concerns likely determine their actual behavior. People may therefore often fail to express their values in actual behaviors unless they pre-commit themselves, in advance, to carrying out those behaviors.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by a United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation Grant #2001–057 to Nira Liberman and Yaacov Trope.

Footnotes

Schwartz's (1992) model of values proposes to distinguish values by the type of the central motivation or goal they express. Using this distinction, Schwartz identified ten types of values: Achievement, power, security, conformity, tradition, benevolence, universalism, self-direction, stimulation and hedonism. Schwartz's value questionnaire lists a set of specific value items that primarily represents each of these value types. For example, the value of benevolence includes the following items: helpful, honest, forgiving, loyal, responsible (for further definitions of value types see also Bardi & Schwartz, 2003; Schwartz, 1992).

Early mornings were reported by Ben Gurion University undergraduates to behighly inconvenient in comparison to the afternoon for participation inexperiments. Note that this manipulation of low-level information overcomes thepotential criticism that people might have concrete plans for the near distant butnot for the distant future, preventing their values to materialize in their near futureplans. It was participants' difficulty to wake up early in the morning and not theiralternative concrete plans for these hours that influenced their behavioralintentions to volunteer to participate in an experiment in the near future.

References

- Ajzen I. Attitudes, traits, and actions: Dispositional prediction of behavior in personality and social psychology. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 20. Academic Press; New York: 1987. pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin. 1977;84:888–918. [Google Scholar]

- Bardi A, Schwartz SH. Values and behaviors: Strength and structure of relations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29:1207–1220. doi: 10.1177/0146167203254602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly A, Chaiken S. The psychology of attitudes. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers; Ft Worth, TX: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Eyal T, Liberman N, Sagristano MD, Trope Y. Resolving value conflicts in planning the future. Ben Gurion University; 2008. unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Feather NT. Bridging the gap between values and actions: Recent applications of the expectancy-value model. In: Higgins ET, Sorrentino RM, editors. Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior. Vol. 2. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1990. pp. 151–192. [Google Scholar]

- Feather NT. Values, valences, and choice: The influence of values on the perceived attractiveness and choice of alternatives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:1135–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Attitudes towards objects as predictors of single and multiple behavioral criteria. Psychological Review. 1974;81:59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DT, Malone PS. The correspondence bias. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:21–38. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Bolger N. Data analysis in social psychology. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 4th ed. Vol. 2. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1998. pp. 233–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kinder DR, Sears DO. Prejudice and politics: Symbolic racism versus racial threats to the good life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1981;40:414–431. [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen CM, Hotte A. Morality and the self: Implications for the when and how of value-attitude-behavior relations. In: Seligman C, Olson JM, Zanna MP, editors. The psychology of values: The Ontario symposium. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman N, Sagristano MD, Trope Y. The effect of temporal distance on level of mental construal. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2002;38:523–534. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman N, Trope Y. The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman N, Trope Y, Stephan E. Psychological distance. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. Vol. 2. Guilford Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Maio GR, Olson JM. Values as truisms: Evidence and implications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:294–311. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W. Personality and assessment. Wiley; New York: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W. Convergences and challenges in the search for consistency. American Psychologist. 1984;39:351–364. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Shoda Y. A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review. 1995;102:246–268. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.102.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum S, Trope Y, Liberman N. Creeping dispositionism: The temporal dynamics of behavior prediction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:485–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohan MJ. A rose by any name? The values construct. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2000;4:255–277. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach M. The nature of human values. Free Press; New York, NY: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ross L, Nisbett RE. The person and the situation: Perspectives on social psychology. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sagiv L, Schwartz SH. Value priorities and readiness for out-group social contact. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Sagiv L, Schwartz SH. Values, priorities, and subjective well-being: Direct relations and congruity effects. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2000;30:177–198. [Google Scholar]

- Sagristano MD, Trope Y, Liberman N. Time-dependent gambling: Odds now, money later. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2002;131:364–376. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.131.3.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SH. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 25. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1992. pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Bilsky W. Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:550–562. [Google Scholar]

- Sears DO, Lau RR, Tyler T, Allen HM., Jr. Self-interest versus symbolic politics in policy attitudes and presidential voting. American Political Science Review. 1980;74:670–684. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman C, Katz AN. The dynamics of value systems. In: Seligman C, Olson JM, Zanna MP, editors. The psychology of values: The Ontario symposium. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tetlock PE. A value pluralism model of ideological reasoning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:819–827. [Google Scholar]

- Trope Y, Liberman N. Temporal construal. Psychological Review. 2003;110:403–421. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.110.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallacher RR, Wegner DM. What do people think they're doing? Action identification and human behavior. Psychological Review. 1987;94:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Verplanken B, Holland RW. Motivated decision making effects on activation and self-centrality of values on choices and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:434–447. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakslak CJ, Nussbaum S, Liberman N, Trope Y. The effect of temporal distance on the structure of the self concept. New York University; 2008. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]