Abstract

Object

Longitudinal multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and histological studies were performed on simvastatin- or atorvastatin-treated rats to evaluate vascular repair mechanisms after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH).

Methods

Primary ICH was induced in adult Wistar rats by direct infusion of 100 µL of autologous blood into the striatal region adjacent to the subventricular zone. Atorvastatin (2 mg/kg), simvastatin (2 mg/kg), or PBS was given orally at 24 hours post-ICH and continued daily for 7 days. The temporal evolution of ICH in each group was assessed by MRI measurements of T2, T1sat, and cerebral blood flow (CBF) in brain areas corresponding to the bulk of the hemorrhage (core), and edematous border (rim). Rats were sacrificed after the final MRI scan at 28 days and histological studies were performed. A small group of sham-operated animals was also studied. Neurobehavioral testing was performed in all animals. Analysis of variance methods were used to compare results from the treatment and control groups, with significance inferred at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

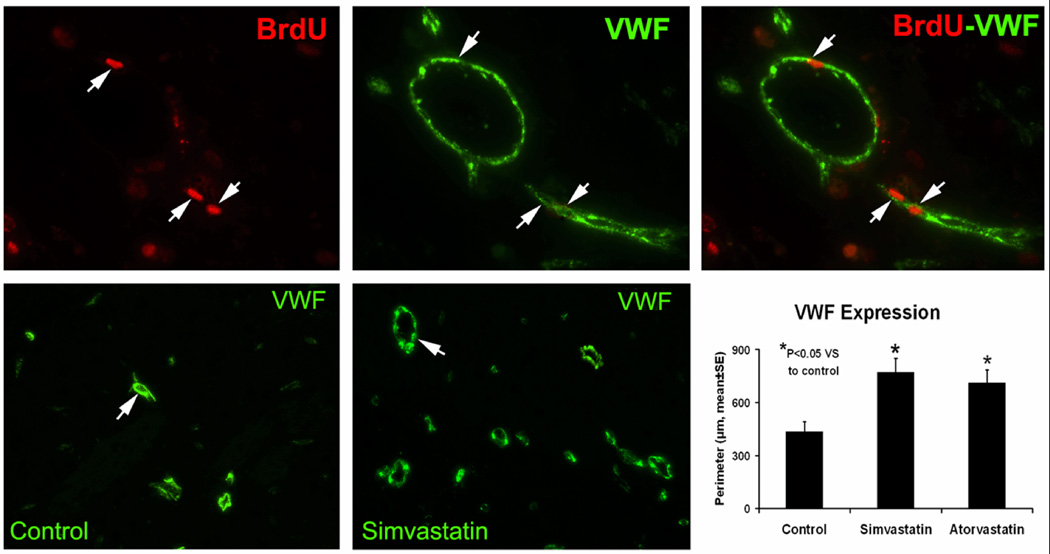

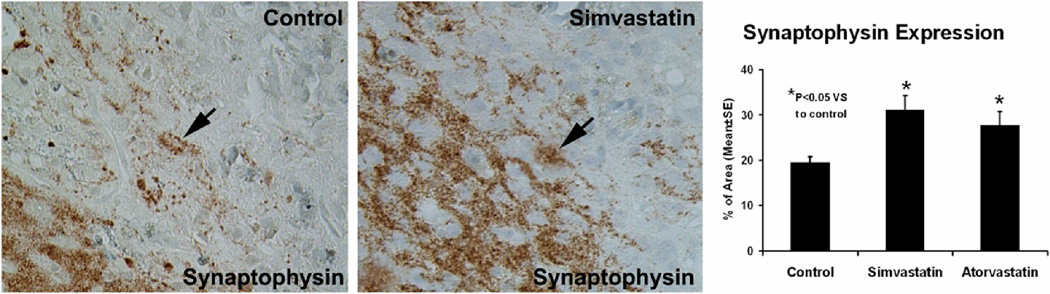

Using histological indices, animals treated with simvastatin and atorvastatin had significantly increased angiogenesis and synaptogenesis in the hematoma rim compared to the control group (p ≤ 0.05). The statin-treated animals exhibited significantly increased CBF in the hematoma rim at 4 weeks, while blood-brain barrier permeability (T1sat) and edema (T2) in the corresponding regions were reduced. Both statin-treated groups showed significant neurological improvement from 2 weeks post-ICH onward.

Conclusion

The results of the present study demonstrate that simvastatin and atorvastatin significantly improve the recovery of rats from ICH, possibly via angiogenesis and synaptic plasticity. In addition, in-vivo multiparametric MRI measurements over time can be effectively applied to the experimental ICH model for longitudinal assessment of the therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: hematoma, multiparametric MRI, synaptophysin, vWF

Statins, 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors, provide neuroprotection with beneficial effects on the nervous and vascular systems by improving or restoring endothelial function, decreasing oxidative stress and vascular inflammation, and enhancing angiogenesis and neurogenesis.10,23 In previous studies we found that atorvastatin and simvastatin enhanced functional outcome, and that atorvastatin enhanced angiogenesis and synaptogenesis after ischemic stroke.3 Similar beneficial effects of simvastatin and atorvastatin have been suggested in relation to hemorrhagic stroke since ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke have a number of common injury-mechanisms.19,26

Contrast mechanisms in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are based on a wide variety of physical parameters, and MRI has been successfully applied to experimental ischemic stroke.27 MRI has a high sensitivity for assessing the temporal evolution of ICH and may be useful in evaluating the impact of therapeutic interventions after experimental ICH in animal models16,20, and eventually in humans. To date, little is known about the longitudinal multiparametric MRI assessment of therapeutic intervention on the experimental model of ICH. In the present study, we used longitudinal multiparametric MRI and immunohistochemistry to assess the therapeutic effects after ICH in rats. We hypothesized that 1) statins reduce edema and vascular injury while promoting angiogenesis and synaptogenesis, and 2) multiparametric MRI can assess the temporal evolution of brain tissue injury and repair and the effects of therapeutic intervention after experimental ICH.

Materials and Methods

Experimental model

All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Wistar rats (270–330 g, n = 22) were anesthetized using isofluorane (3.5% induction, 1.0–1.5% maintenance) in a 2:1 mixture of N2O/O2. Core temperature was maintained at 36–37°C throughout all surgical and MRI procedures. Primary ICH was induced by direct infusion of autologous whole blood into the striatal region adjacent to the subventricular zone (SVZ).16,20–22 For the acute time point study, the right femoral artery and vein were cannulated for monitoring of blood pressure and gases and for administration of MR contrast agent (Gd-DTPA: 0.2 mmol/kg/body weight). For follow-up studies, the contrast gent was administered through a tail vein.

At 24-hours post-ICH, animals were randomly assigned to atorvastatin (2 mg/kg), simvastatin (2 mg/kg), or PBS (control) treatment groups (n = 6/group). The dosage was selected based on the previous study.21 Treatment was given by oral gavage starting 24-hours post-ICH and continued daily for 7 days. Neurobehavioral testing consisted of a modified neurological severity score and cornering tests that were performed at 1, 4, 7, 14, 21 and 28 days post-ICH.14,16,20–22

A group of sham animals (n = 4) was subjected to the same manipulations as ICH rats (i.e. the needle was inserted into the brain at the specified coordinates, left in place for 10 minutes and then withdrawn) but no blood was injected. This group was also studied. Neurological function for sham animals was tested at 0, 1, 3, 7 days post-injury. Sham animals were sacrificed at 7 days for histological evaluation.

MR imaging

All MRI measurements were performed using a 7 Tesla, 20-cm bore superconducting magnet (Magnex Scientific, Inc., Abingdon, UK) interfaced to a Bruker Avance console running Paravision 3.0.2 (Bruker Biospin MRI, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA).14,16 After being anesthetized, the rats were placed in a holder equipped with a nose cone and ear bars. A 3-plane scout imaging sequence was used to iteratively adjust the position of the animal’s head until the central slice was located at the level of the largest portion of the hematoma. A series of MR images including spin-lattice (T1) and spin-spin (T2) relaxation weighted imaging (T1WI and T2WI, respectively), diffusion-weighted imaging, magnetization transfer (MT) weighted imaging, perfusion, blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability and susceptibility weighted imaging were acquired using a 32-mm field of view (FOV). The MRI scans were performed pre-ICH (baseline), 1–3 hours after ICH onset, and at 1, 2, 7, 14 and 28 days post-ICH.

T1sat measurements

Estimates of T1sat were acquired using an imaging variant of the T-one by multiple readout pulses (TOMROP) sequence.2,9 Measurements of T1 in the presence of off-resonance saturation of the bound proton signal (T1sat), an MT-related parameter, were also generated using this method. This was done by inserting two continuous wave RF saturation pulses into the Look-Locker sequence: the first (4.5 seconds long) immediately before the inversion pulse and the second (40 ms long) after the signal acquisition. The offset frequency of saturation pulses was 8 kHz, and the rotational frequency of B1 field was 0.5 kHz. Initially, the longitudinal magnetization was inverted using an 8 ms non-selective adiabatic hyperbolic secant pulse. One phase encode line of 32 small-tip angle gradient echo (GE) images (TE = 7.0 ms) was acquired at 80-ms intervals after each inversion. With this sequence, a single slice T1sat map was obtained in ~9 minutes (TR = 8 seconds, 128 × 64 matrix, 2-mm slice thickness).

T2 measurements

The T2 relaxation time was measured using a standard Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) 2-dimensional Fourier transform (2DFT) multi-slice (i.e., 13 slices each of 1-mm thickness) multi-echo (6 echoes) MRI sequence. Echo times (TEs) were 15, 30, 45, 60, 75 and 90 ms, and repetition time (TR) was 5.0 seconds. Images were produced using a 128 × 64 matrix. Total time for the entire sequence was 5 minutes and 20 seconds.

Perfusion measurements

The CBF estimates were acquired using an arterial spin labeling (ASL) technique.5 The ASL method is based on the selective inversion of inflowing blood water protons at the level of the carotid arteries prior to 1H MRI measurement in the brain. The inversion pulse was applied for 1 second at a B1 amplitude of 0.3 kHz, and had a frequency offset of ± 6 kHz. It was followed by a SE sequence with TR/TE = 1060 ms/40 ms. Four averages of the image were acquired with the gradient polarities and the RF pulse frequency offsets reversed to remove any gradient asymmetries in the axial direction. The labeled slice was 1-mm thick and was located approximately 2 cm distal to the imaging slice. The image slice was 2-mm thick and was acquired using a 64 × 64 matrix. Total time for the entire series was 18 minutes.

MR Data processing and analysis

All MR data were transferred to a UNIX system for image processing and analysis. All MR images were reconstructed using a 128 × 128 matrix. T2 maps were produced on a pixel-by-pixel basis using a linear least-square fit. The 28-day post-ICH T2 maps were co-registered to corresponding histology sections using Eigentool software. For each animal, the T2 map with the biggest area of hematoma acutely was chosen for the analysis of temporal evolution. T2 maps at later points were co-registered to the acute time point T2 map. Regions of interest (ROIs) representing hematoma core and edematous border were identified by windowing T2 values. Abnormal T2 values were identified as > ±1 standard deviation. At the acute time point, T2 values were low in the core and high in the rim. At time points ≥ 24 hours post ICH, however, these trends reversed with T2 values in the core becoming elevated and T2 values in the rim area decreasing below normal levels. All other MRI parameter maps were co-registered to the T2 maps. The MRI parameters were measured in these selected ROIs and the corresponding contralateral regions.

Immunohistochemistry

At the 4th week after MRI scan, the animals were anesthetized with ketamine (44 mg/kg) and xylazine (13 mg/kg) administered intraperitoneally. They were then perfused transcardially with PBS, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The intact brain was immediately removed and immersed in fixative overnight. For the purpose of mitotic labeling of newly synthesized DNA, all rats received daily injections of bromodeoxyuridine (100 mg/kg) administered intraperitoneally (BrdU; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) starting 24 hours after ICH and then subsequently for the next 13 days. Six coronal slides from every 40th 6-um-thick slides of the block (bregma 0.1 mm to – 0.86 mm) in each rat were specifically selected for immunohistochemical staining for von Willebrand (vWF) monoclonal antibody (dilution 1:100; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and BrdU monoclonal antibody (dilution 1:200; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) or synaptophysin monoclonal antibody, clone SY 38 (dilution 1:40; Boehringer Mannheim Biochemica, Indianapolis, IN).20

For measurement of vascular perimeters and synaptophysin immunoreactivity, 6 immunostained coronal sections and 8 consecutive fields of view from the ipsilateral striatum which is adjacent to the hemotoma in each section were digitized using a magnification of 20 (Olympus BX40; Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan) on a 3-color CCD video camera (model DXC-970MD; Sony Corp., Tokyo, Japan) interfaced with the MCID computer imaging analysis system (Imaging Research, Inc., St. Catharine’s, Ontario, Canada). The numbers of vessels and their perimeters were counted and the total vascular perimeters were calculated throughout each field of view. The percentage of positive area for synaptophysin was measured.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses of the ipsilateral/contralateral values of MR parameters at various times post-ICH, between statin-treated and control groups were evaluated using mixed models analysis of variance (ANOVA) techniques, which take into account the possible correlation among the repeated time points within the same animal. Immunohistological measures of synaptophysin and vWF expression between groups were compared using ANOVA. Data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was inferred at p ≤ 0.05. All measurements were performed by observers blinded to individual treatments.

Results

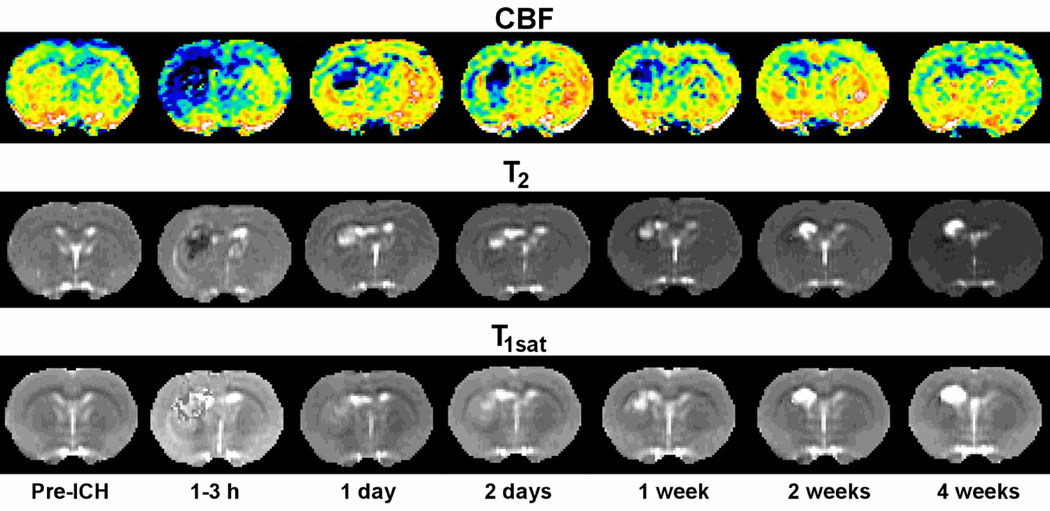

All ICH animals showed similar deficits prior to randomization at 1 day post ICH. Both statin-treated groups showed significant neurobehavioral improvement from 2 weeks post-ICH onward compared to controls.14 Figure 1 shows an example of quantitative CBF, T2, and T1sat maps from a representative atorvastatin-treated rat at various times before and after experimental ICH. In the sham group, there was no apparent change in brain tissue staining (i.e., no hemorrhage or tissue loss) and no effect on behavioral function one week after surgery. Based on these results and previous studies,30 we did not expect to see any measurable changes in the sham group, therefore, they were not examined by MRI or additional immunohistochemistry.

Fig. 1.

Examples of quantitative cerebral blood flow, T2, and T1sat maps at various times before and after experimental ICH in representative atorvastatin-treated rats. The CBF maps (top row) indicate normal flow before ICH that decreases severely after ICH, particularly in the central core region. The T2 maps (middle row) show a dark central core region (low T2) and adjacent surrounding bright rim (high T2) acutely that reverses in intensity at 24 hours and beyond. Increased blood-brain barrier permeability was noted in both core and rim areas at 24 hours that increased further in the core while stabilizing or decreasing slightly in the rim in the T1sat maps (bottom row).

Statin Modulates BBB Permeability

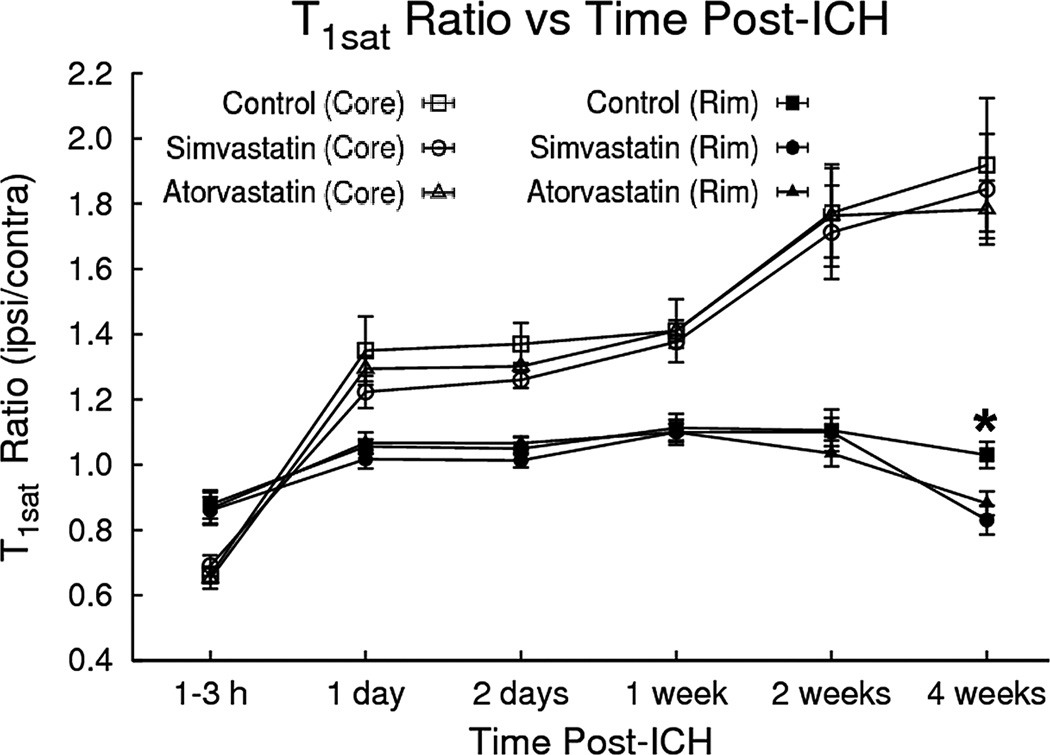

In a previous study we showed the magnetization transfer-related parameter T1sat was responsive to changes in BBB permeability in ICH-affected brain tissue.14 In the current study, the ipsilateral/contralateral T1sat ratios decreased acutely in the core region immediately post-ICH and then became elevated at later times, whereas only minor T1sat changes were noted in the rim (Figure 2). Statin intervention significantly decreased T1sat values in the rim at 4 weeks in both statin treatment groups as compared to the control group (i.e., p = 0.02 for the atorvastatin-treated group, p = 0.003 for the simvastatin-treated group).

Fig. 2.

T1sat ratios (ipsilateral/contralateral) plotted as a function of time after ICH. T1sat values in the core region decreased initially and then became significantly elevated at later times. Only minor T1sat changes were seen in the rim. However, at 4 weeks, the simvastatin/atorvastatin intervention decreased T1sat values in the rim as compared to the control group.

Statin Decreases Edema

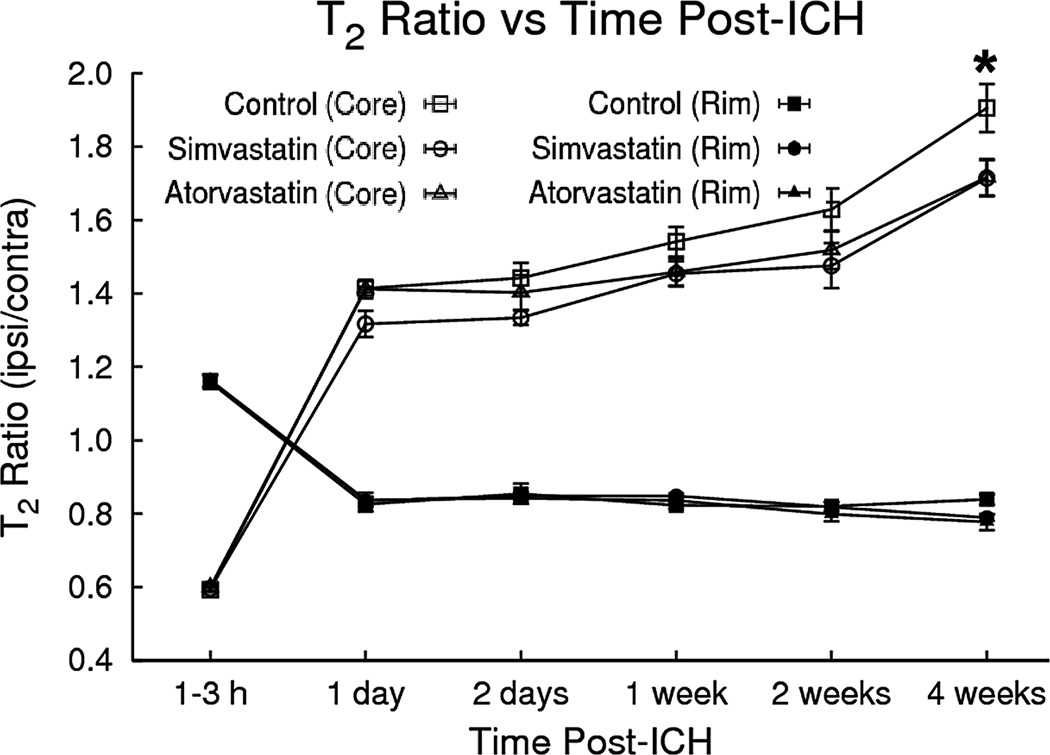

Elevated ipsilateral/contralateral T2 ratios in the hematoma and surrounding tissue correspond to increased water content, or edema relative to the corresponding contralateral regions (Fig. 3). The ipsilateral/contralateral T2 ratio changes were distinct between the core and rim areas after ICH. The T2 values in the core declined acutely and then became elevated at later times relative to corresponding contralateral regions, whereas T2 in the rim was elevated acutely and then decreased at later times relative to contralateral regions. After both statin therapies, the T2 ratios significantly decreased at 4 weeks in both the core (i.e., p = 0.029 for atorvastatin, p = 0.027 for simvastatin) and rim (p = 0.017 for atorvastatin, p = 0.047 for simvastatin) as compared to the control group.

Fig. 3.

Plot of T2 ratios (ipsilateral/contralateral) as a function of time after ICH onset for regions in the central core and surrounding rim of the lesion. In the core, T2 declined significantly at the acute stage and then became significantly elevated at later times relative to the corresponding contralateral region. Conversely, T2 ratios in the rim were elevated acutely and then decreased at later times. Simvastatin/atorvastatin therapies significantly lowered T2 values in the core and rim at 4 weeks after ICH.

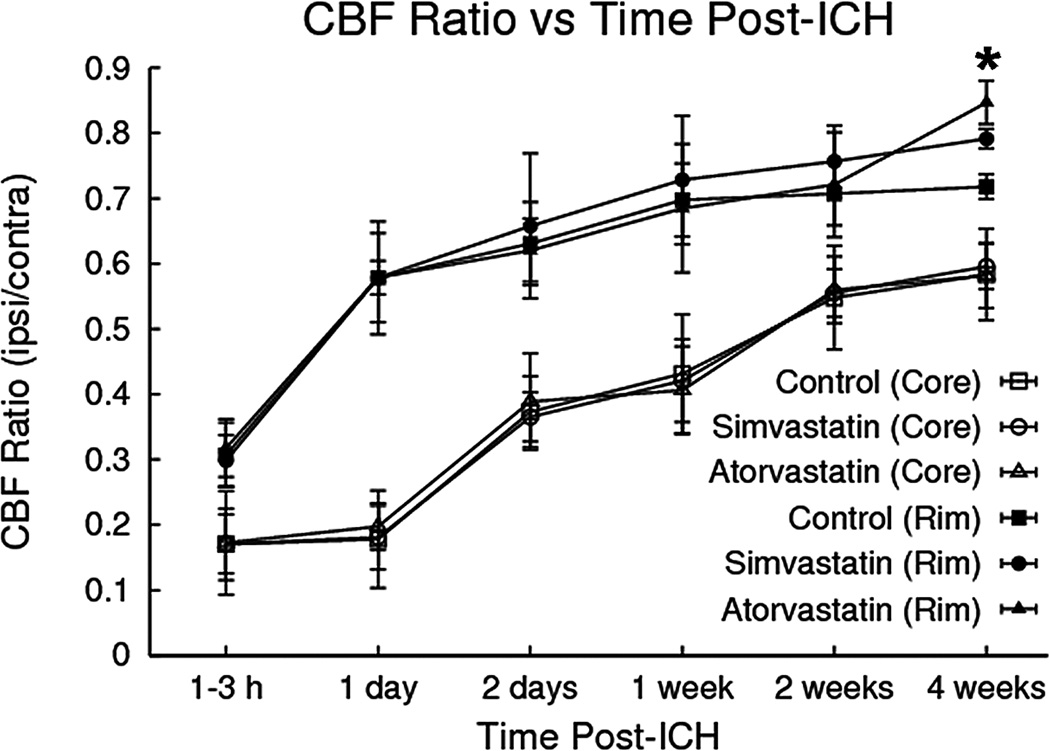

Statin Increases CBF

Representative examples of quantitative cerebral blood flow at various times and ipsilateral/contralateral CBF ratios for core and adjacent rim areas plotted as a function of time are shown in the top row of Figure 1 and Figure 4, respectively. CBF values in both the core and rim regions decreased relative to contralateral regions at all time points. Furthermore, CBF values in the core were lower than the rim area at all time points. Treatment with statin significantly increased CBF at 4 weeks around the hematoma as compared to the control group (i.e., p = 0.0015 for atorvastatin, p = 0.043 for simvastatin), but did not differ significantly between statin treatments (p = 0.12).

Fig. 4.

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) ratios (ipsilateral/contralateral) plotted as a function of time. CBF in both the core and rim regions decreased significantly relative to contralateral regions at all time points. Treatment with either simvastatin or atorvastatin significantly increased CBF in the hematoma rim at 4 weeks.

Statin Induces Angiogenesis

After ICH, the microvessels in the boundary zone around the hemorrhage clot had very narrow clefts between the vessels and the parenchyma and few enlarged, thin-walled or intussusception vessels were found. To determine if statin promoted the proliferation of microvessels in this area, the perimeter of vessels 4 weeks after ICH was determined using vWF immunostaining (Figure 5). Results indicated that the total perimeters of vWF-positive microvessels in set areas in the boundary zone of the statin-treated groups were significantly higher as compared with the PBS group (i.e., p = 0.016 for atorvastatin, p = 0.004 for simvastatin). The simvastatin-treated group, however, showed no significant difference from the atorvastatin group (p = 0.554).

Fig. 5.

Representative immunostaining and quantitative immunoreactivities of vWF in the the ICH border zone. Upper panels show BrdU (left) and vWF (center) immunostaining and colocalization of BrdU-vWF (right) for a subpopulation of cells located near the injured site for a simvastatin-treated animal. Arrows indicate cells that stained positively for both BrdU and vWF. vWF results are shown in the lower panels for control (left) and simvastatin (center) treatment groups, respectively. Quantitative immunoreactivities for all three groups are presented as bar graphs in the lower right panel.

Statin increases synaptophysin expression

The functional benefits derived from statin treatment of ICH from our previous results suggest an effect on synaptogenesis.14 Synaptophysin, a synaptic vesicle-associated protein, is a marker for presynaptic plasticity and synaptogenesis. Four weeks after ICH, the density of synaptophysin signals in the boundary zone was less than in the intact striatum (Fig. 6). After treatment with statin, the density significantly increased in this area compared to the control rats. Significantly increased synaptophysin expression was observed in the statin-treated rats as compared with control (i.e., p = 0.048 for atorvastatin, p = 0.007 for simvastatin). No significant difference was detected between the simvastatin- and atorvastatin-treated groups (p = 0.384). These data suggest that statin treatment in ICH may protect synapses or induce synaptogenesis in the boundary zone.

Fig. 6.

Representative immunostaining and quantitative immunoreactivities of synaptophysin are shown for the ICH border zone of control and simvastatin-treated rats (left and center panels, respectively). A higher percentage per area of cells positively reacting to synaptophysin is seen in the sections derived from simvastatin-treated vs control rats. Quantitative immunoreactivities for all three groups are presented as a bar graph on the right side.

Discussion

Approximately 80% of primary ICHs originate from the spontaneous rupture of small vessels which are impaired by long-standing or uncontrolled arterial hypertension.1 The initial local intracranial bleeding imposing both physical and chemical stress causes a secondary and more destructive influence on brain vessels, including brain edema formation, impairing CBF, and increasing BBB permeability.15 These changes in the pathophysiology of cerebral damage after ICH can be tracked and assessed by the quantitative MRI in animal models.14

Perihematomal injury and the subsequent inflammatory cascades initiated by the coagulation products and the toxic blood breakdown products lead to disruption of the BBB.28 The increasing BBB permeability contributes to brain edema formation and facilitates inflammatory cytokine migration, resulting in sustained neurological deterioration. Although known as potent cholesterol-lowering drugs, the statins can produce a number of pleiotropic effects, including inhibition of a number of isoprenoid intermediates.15,25 Ifergan and colleagues have shown that statins can stabilize the BBB integrity by interfering with isoprenylation events.11 The current study also demonstrated that statins attenuate the change in BBB permeability after ICH.

In addition to BBB disruption, blood coagulation and breakdown products can induce inflammation and osmotic shifts in tissue water content, which are responsible for edema development after ICH. A number of studies have shown that increased brain edema around the hematoma is associated with poor outcome in patients.29 In this study, we have shown that brain edema developed and peaked around the hematoma within hours after onset, while in the core area, the edema progressed further up until 4 weeks. After statin therapy, brain edema decreased to about 10% to 20% in both the rim and core. Jung et al using collagenase-induced ICH animals observed that statin decreased infiltration of leukocytes and microglia, and increased endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression.13 Therefore, statins may protect the brain vessels from inflammation and improve endothelial function by enhancing nitric oxide bioavailability.

Statins have been shown to enhance CBF in both clinical and experimental ischemic stroke.6,7 Enhancement of CBF can attenuate the ischemic neuronal injury and improve neurological recovery. Although it is still controversial whether secondary cerebral ischemia occurs in the brain after ICH, several studies have reported that both CBF and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen were reduced in the perihematoma area.1,16,28 In our study, CBF was found to be low around the hematoma soon after ICH, compared with the contralateral side. Statin intervention tends to increase CBF around the hematoma starting at 1 week. After 4 weeks, CBF in the ipsilateral hemisphere of the treatment group recovered to as much as 80% of the contralateral levels (i.e., significantly different from the control group).

Statistically significant improvement of CBF was detected in the fourth week but not at earlier time points, suggesting that the neuroprotective effect of statins may be insufficient to contribute to the improvement of pathophysiological change in the early stage after ICH. Angiogenesis along the border zone, detected 4 weeks after ICH, may be a pathway for enhanced CBF at the later stage of ICH. Although significant changes in CBF were seen in the statin-treated animals as compared to controls, it is doubtful that the magnitude of the CBF improvement seen could be attributed entirely to angiogenesis. It is probably more likely that at least some of the beneficial effects of statin treatment in ICH are due to protection of existing blood vessels in the rim area from further ICH-induced injury or possibly a combination of vascular protection and angiogenesis. There is increasing evidence that statins increase angiogenesis by improving endothelial function via an increase in endothelium-derived nitric oxide.8,15 A direct link has been revealed between statins and the serine/threonine protein kinase Akt that regulates multiple angiogenic processes in endothelial cells.15

Extensive synaptic reorganization and neurological functional recovery have been attributed to the reduction of neurological deficits after stroke and brain trauma.3,17 It appears that synaptophysin may play a critical role in regulating synapse formation.24 In a study using an animal model of stroke, treatment with low-dose atorvastatin initiated 24 hours after injury significantly promoted synaptophysin expression in the ischemic boundary and improved functional outcome.3 In our current study, synaptophysin density significantly increases in the boundary zone around the hematoma after statin treatment. Both the simvastatin and atorvastatin groups had significant neurological improvement from 2 weeks post-ICH onwards.14 Therefore, enhanced synaptic formation by statins may contribute to functional outcome. The vascular recovery may be important in promoting synapse formation, because angiogenesis has been linked to improved neuronal recovery.4 However, it is undetermined whether appropriate synaptic connections can form and integrate into the adult brain.

Statins penetrate the blood-brain barrier (BBB) with different efficiency, depending on their lipophilicity.12 Despite simvastatin having a greater permeability across the BBB compared to atorvastatin,31 the present data indicate that at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day, simvastatin and atorvastatin have similar protective and restorative effects on ICH.

Several limitations should be considered in the present study. Rodent ICH models have limitations when comparing outcome measures to the human ICH condition. The resolution of the clot and functional improvement is faster in both the collagenase and the injection experimental models of ICH, the latter method being used in this experiment. Extrapolation to human recovery with statin use cannot be made. There also have been limitations of MRI measurements early after ICH in the rodent models noted by other authors; the mass effect of the clot makes discernment of T2 significance difficult.18 This may be a reason why we could only find significant changes in MRI parameters at the latest time point after ICH.

Probably the most important shortcoming of the present study is the small number of animals that were studied, which somewhat precludes an extensive analysis of the various correlative comparisons that could be made between MRI, neurobehavioral and histological data. While it would be interesting and desirable to test for such relationships, the small sample sizes available in the present study lack the statistical power that would be needed to perform such an analysis. Another problem occurs when trying to compare MRI data to histology and immunohistochemistry data due to differences in slice thickness and distortion of the sections caused by tissue shrinkage that occurs during histological preparation. We allow roughly 25% to account for shrinkage in the slice direction, but the in-plane shrinkage of the sections can be non-linear and moredifficult to correct for.

Conclusions

Simvastatin and atorvastatin have a beneficial effect after experimental ICH due to a vascular restorative mechanism demonstrated by histochemical and MRI evidence of angiogenesis and improved vascular functioning in the ICH border zone. The ICH region also shows correlative evidence of neuronal recovery with increased synaptophysin expression.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Susan MacPhee-Gray for editorial assistance.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grant RO1 NS058581-01A1 (to D.M.S.).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

References

- 1.Ariesen MJ, Claus SP, Rinkel GJ, Algra A. Risk factors for intracerebral hemorrhage in the general population: a systematic review. Stroke. 2003;34:2060–2065. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000080678.09344.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brix G, Schad LR, Deimling M, Lorenz WJ. Fast and precise T1 imaging using a TOMROP sequence. Magn Reson Imaging. 1990;8:351–356. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(90)90041-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J, Zhang ZG, Li Y, Wang Y, Wang L, Jiang H, et al. Statins induce angiogenesis, neurogenesis, and synaptogenesis after stroke. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:743–751. doi: 10.1002/ana.10555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chopp M, Zhang ZG, Jiang Q. Neurogenesis, angiogenesis, and MRI indices of functional recovery from stroke. Stroke. 2007;38:827–831. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000250235.80253.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Detre JA, Leigh JS, Williams DS, Koretsky AP. Perfusion imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1992;23:37–45. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910230106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Endres M. Statins and stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:1093–1110. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Endres M, Laufs U, Huang Z, Nakamura T, Huang P, Moskowitz MA, et al. Stroke protection by 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl (HMG)-CoA reductase inhibitors mediated by endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8880–8885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Endres M, Laufs U, Liao JK, Moskowitz MA. Targeting eNOS for stroke protection. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ewing JR, Jiang Q, Boska M, Zhang ZG, Brown SL, Li GH, et al. T1 and magnetization transfer at 7 Tesla in acute ischemic infarct in the rat. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41:696–705. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199904)41:4<696::aid-mrm7>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furberg CD. Natural statins and stroke risk. Circulation. 1999;99:185–188. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ifergan I, Wosik K, Cayrol R, Kebir H, Auger C, Bernard M, et al. Statins reduce human blood-brain barrier permeability and restrict leukocyte migration: relevance to multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:45–55. doi: 10.1002/ana.20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joshi HN, Fakes MG, Serajuddin AT. Differentiation of 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme a reductase inhibitors by their relative lipophilicity. Pharm Pharmacol Commun. 1999;5:269–271. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung KH, Chu K, Jeong SW, Han SY, Lee ST, Kim JY, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, atorvastatin, promotes sensorimotor recovery, suppressing acute inflammatory reaction after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2004;35:1744–1749. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000131270.45822.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karki K, Knight RA, Han Y, Yang D, Zhang J, Ledbetter KA, et al. Simvastatin and atorvastatin improve neurological outcome after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2009;40:3384–3389. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.544395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinlay S. Potential vascular benefits of statins. Am J Med. 2005;118 Suppl 12A:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knight RA, Han Y, Nagaraja TN, Whitton P, Ding J, Chopp M, et al. Temporal MRI assessment of intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. Stroke. 2008;39:2596–2602. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.506683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu D, Goussev A, Chen J, Pannu P, Li Y, Mahmood A, et al. Atorvastatin reduces neurological deficit and increases synaptogenesis, angiogenesis, and neuronal survival in rats subjected to traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:21–32. doi: 10.1089/089771504772695913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacLellan CL, Silasi G, Poon CC, Edmundson CL, Buist R, Peeling J, et al. Intracerebral hemorrhage models in rat: comparing collagenase to blood infusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:516–525. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qureshi AI, Tuhrim S, Broderick JP, Batjer HH, Hondo H, Hanley DF. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. N Eng J Med. 2001;344:1450–1460. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seyfried D, Ding J, Han Y, Li Y, Chen J, Chopp M. Effects of intravenous administration of human bone marrow stromal cells after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:313–318. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.104.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seyfried D, Han Y, Lu D, Chen J, Bydon A, Chopp M. Improvement in neurological outcome after administration of atorvastatin following experimental intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:104–107. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.101.1.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seyfried DM, Han Y, Yang D, Ding J, Savant-Bhonsale S, Shukairy MS, et al. Mannitol enhances delivery of marrow stromal cells to the brain after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Brain Res. 2008;1224:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.05.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takemoto M, Liao JK. Pleiotropic effects of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibitors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1712–1719. doi: 10.1161/hq1101.098486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarsa L, Goda Y. Synaptophysin regulates activity-dependent synapse formation in cultured hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1012–1016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022575999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaughan CJ, Murphy MB, Buckley BM. Statins do more than just lower cholesterol. Lancet. 1996;348:1079–1082. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)05190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner KR, Broderick JP. Hemorrhagic stroke: pathophysiological mechanisms and neuroprotective treatments. In: Lo EH, Marwah J, editors. Neuroprotection. Scottsdale: Prominent Press; 2002. pp. 471–508. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber R, Ramos-Cabrer P, Hoehn M. Present status of magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy in animal stroke models. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:591–604. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xi G, Keep RF, Hoff JT. Mechanisms of brain injury after intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:53–63. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xi G, Keep RF, Hoff JT. Pathophysiology of brain edema formation. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2002;13:371–383. doi: 10.1016/s1042-3680(02)00007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang S, Song S, Hua Y, Nakamura T, Keep RF, Xi G. Effects of thrombin on neurogenesis after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2008;39:2079–2084. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.508911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zacco A, Togo J, Spence K, Ellis A, Lloyd D, Furlong S, et al. 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors protect cortical neurons from excitotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11104–11111. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11104.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]