Abstract

Little is known about the influence of relationship characteristics on a woman’s desire for a baby with her partner. This study addresses that gap, using data from a study of 1,114 low-income women in the southeast who were in a relationship. Controlling for sociodemographic factors, women who were in more established relationships, who had not had a previous child with their partner, or who had higher expectations of their partner were generally more likely to want a baby with him. In investigating women’s childbearing desires, it is important to consider not only individual characteristics but also women’s relationship characteristics.

Keywords: fertility desires, fertility determinants, partners, relationships, unintended pregnancy

Unintended pregnancy has potentially serious negative consequences for the health and well-being of women, children, and their families (Institute of Medicine, 1995), and nearly half (49%) of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended (Finer & Henshaw, 2006). The proportion of pregnancies that are unintended is even higher among women who are poor (62%), Black (69%), or unmarried (74%) (Finer & Henshaw). Although considerable research has explored the complex, interconnected determinants of unintended pregnancy (Institute of Medicine), one aspect of women’s lives that may significantly contribute to unintended pregnancy has been little considered, namely, their relationships with their sexual partners (Goldscheider & Kaufman, 1996).

In recent decades, the significance of women’s relationship context to their feelings about child-bearing has increased because the link between marriage and childbearing has eroded. Whereas in 1970, 11% of all children in the United States were born out of wedlock, by 2000 the proportion had risen to 31% among the population as a whole and to 65% among Blacks (Downs, 2002). Women from disadvantaged backgrounds are especially likely to experience nonmarital pregnancies (Driscoll et al., 1999). Women have also become increasingly likely to have a series of sexual relationships instead of a single partner throughout their lives (Turner, Danella, & Rogers, 1995), in part because of an increase in rates of divorce, remarriage, and cohabitation (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002). The increasingly unstable nature of women’s relationships suggests that they may now be less likely than in the past to have a lifetime vision of the number of children they want to have and are more likely to consider whether they want to have a child in the context of each relationship (Bumpass, 1991).

Even within relationships, women’s desire for a baby with their partner is likely not to be fixed but to change over time, as relationships evolve and life circumstances change. For that reason, the present study addresses the question of how the relationship context may influence the degree to which women want to have a baby with their current partner at a given point in time (during a specific 30-day period of the relationship). Relationship factors that lead women not to want a pregnancy at a given point in time are likely to contribute to their vulnerability to unintended pregnancy. Because unintended pregnancy is, by definition, a pregnancy that occurs at a time in the life of a woman during which she does not want to become pregnant, this article advances our understanding of the phenomenon of unintended pregnancy and the relationship factors that may make women more likely to have an unintended pregnancy.

Because research has demonstrated that many women have ambivalent feelings about pregnancy (Kendall et al., 2005; Luker, 1999), this paper examines desire for a baby not as a yes or no question but rather allows a continuum of desire. The study uses survey data from a sample of primarily low-income Black and White women in two southeastern cities. The question of how the relationship context may influence women’s desire to have a baby with their current partner may be particularly relevant to low-income populations such as this one, because they tend to experience high levels of relationship instability and high rates of nonmarital and unintended pregnancy (Driscoll et al., 1999; Edin & Kefalas, 2005; Finer & Henshaw, 2006).

Previous Research

In a recent qualitative study exploring the concepts of intended, planned, and wanted pregnancy, Fischer, Stanford, Jameson, and DeWitt (1999) found that factors related to women’s relationships were central to their feelings about their pregnancies. No quantitative research has comprehensively investigated the effect of relationship characteristics on women’s feelings about having a baby, however. Research in this area typically includes only one or two variables related to women’s relationships (such as marital/cohabitation status) and does not consider other aspects of the relationship such as its quality or nature. Furthermore, some of the most relevant literature in this area dates from the 1970s. Because of changes in the patterns of relationships and childbearing since that time, the influence of relationship characteristics on women’s fertility desires may also have changed.

Findings from preliminary qualitative research conducted for the present study (Koo, Woodsong, & Shedlin, 1999) as well as the limited existing research on this topic suggested four dimensions of women’s relationships that are likely to influence their feelings about having a baby with their partner. These dimensions are the following: the quality of the relationship, how established it is, previous childbearing by the partner or by the couple, and the women’s expectations of support from both the partner and his family if they were to have a baby. We review below the relatively little that is known about how each of these dimensions is related to women’s feelings about having a child with the partner.

Quality of the Relationship

The quality of the relationship has been shown to affect women’s feelings about childbearing. Fischer et al. (1999) found that women were more likely to want a pregnancy if they expressed positive feelings about their partner. Some research has also investigated the effects of discord in a relationship on the desire to have children, but findings have been mixed. Whereas some studies suggested that women in troubled relationships may want children to improve the husband-wife relationship (Hoffman & Manis, 1979) or to reduce uncertainty in their lives (Friedman, Hechter, & Kanazawa, 1994), other studies have found that women in marriages on the brink of divorce are less likely to have children (Myers, 1997; Thornton, 1978).

Degree to Which the Relationship is Established

One measure of how established the relationship is relates to whether couples are married, cohabiting, or noncohabiting. It is well documented that pregnancies to women who are married to their partners are more likely to be intended (and by inference, desired) than pregnancies to women who are not married (e.g., Finer & Henshaw, 2006; Forrest, 1994). Similarly, in the only quantitative study to date that has addressed the question of whether a woman wanted to conceive with a particular partner, Zabin, Huggins, Emerson, and Cullins (2000) found that women were more likely to say they did not want to conceive with their current partner if he was not a husband, cohabiting partner, or a serious relationship.

Expectations for the duration of the relationship are another measure of how established the relationship is, and this measure has also been found to affect desire for a baby. Findings from our own preliminary qualitative research and the study by Fischer et al. (1999) indicated that women are more likely to want a pregnancy with their partner if they expect their relationships to continue.

Previous Childbearing

Some research suggested that, regardless of the number of children they may have from previous relationships, women who have not already had a child with their current partner may want to have at least one child with him either to achieve their concept of a family (Hoffman & Manis, 1979; Thornton, 1978) or to cement the relationship (Westoff, 1977). In contrast, other research has found that among remarried couples, the primary drive for childbearing is for each partner to have a child of his or her own, not for the couple to have a child together (Stewart, 2002). That is, if each partner already had a biological child from a previous relationship, the couple would feel less impelled to have a child together.

Women’s Expectations

Finally, several factors related to women’s expectations of their partner and his family if they were to have a baby with him have been found to influence their feelings about pregnancy. Findings from our preliminary qualitative research and the study by Fischer et al. (1999) indicated that women are more likely to want a pregnancy if they expect financial and emotional support from their partners. Our preliminary qualitative research suggested that women also take into account how good a father they think their partner would be. Some women also mentioned an unexpected facilitating factor: If they thought that they would continue to have a relationship with the partner’s relatives if they had a baby, even if the relationship with him ended, then they would be more favorable toward having a baby with him. Previous research showing the importance of extended kin networks in Black American families (Aschenbrenner, 1973; Stack, 1974) is consistent with this reason for wanting a baby with the partner.

Hypotheses

Based on this previous research, we expect that each of these four dimensions will affect women’s feelings about having a baby with their partner. Because we collected extensive information in our survey on the characteristics of women’s relationships, we have measures for all of these dimensions. Although the survey did not include questions related to some of the measures used in previous research (such as the level of discord in the relationship), it did include many measures of relationship quality, stability, and expectations that had not been previously explored, allowing us to develop each of the dimensions more fully and to test the following hypotheses. We hypothesize that women with the following relationship characteristics will have a stronger desire for a baby with their partner:

women with “better quality” relationships (as measured by communication with their partner, relationship satisfaction, and sexual exclusivity);

women with more established relationships (as measured by marriage/cohabitation status, actual relationship duration, and expected future duration of the relationship);

women who have not already had a baby with their partner and women whose partner has not had a baby at all; and

women who have positive expectations of the partner and his family if they were to have a baby (as measured by expectations that he would provide financial and emotional support; that he would be a good father; and that her relationship with his relatives would continue if they had a child, even if her relationship with him ended).

Control Variables

Several sociodemographic factors are known to influence fertility and thus can also be expected to influence a woman’s desire for a child with a partner. These include age, race, education, employment outside the home, poverty status, and parity or the number of births a woman already has had. Typically, younger women and those with fewer children are more likely to become pregnant, and minority women, those who are less educated, not employed, and living in poverty have more children (e.g., Martin et al., 2003). It is reasonable to consider that these demographic factors would also increase the likelihood that women would want to have a baby with their partners, and thus we take them into account in testing the hypotheses regarding the influence of relationship factors.

Inclusion of Both Women Who Have Had a Pregnancy and Those Who Have Not

Most past research in this area is limited to women’s feelings about pregnancies they have had. A problem with this approach, however, is that it excludes from the analysis women who have not had a recent pregnancy, and these women’s feelings about childbearing are likely to differ in important ways from those who have had a recent pregnancy. For example, women who have not had a recent pregnancy are probably less likely to have wanted a child, and they may also be better at using contraception to avoid an unwanted pregnancy. The exclusion of women who have not had a recent pregnancy thus provides an incomplete and possibly biased picture of women’s desires for a child. For this reason, in our research, we include both women who have had a recent pregnancy and those who have not. As a result, we are able to develop a more complete and unbiased picture of how the relationship context affects women’s desire for a baby with their partner.

Method

Data

We used data from a longitudinal study conducted in Atlanta, Georgia, and Charlotte, North Carolina. We collected baseline data between July 1993 and October 1994 from women visiting public family planning and postpartum clinics and maternity wards in each city. We selected the study sample using probability sampling methods. We included all clinic sessions for most types of clinics, but for the clinics in Atlanta with the largest number of clients (family planning and postpartum clinics), we sampled clinic sessions. In both cities, we included either all eligible women or a systematic sample of women seen in the selected clinic sessions. To be eligible for the study, women had to be Black or non-Hispanic White and to be choosing a contraceptive method that they had not used in the previous 3 months. Only Black and non-Hispanic White women were included because, at the time of the baseline survey, very few women of other racial and ethnic groups frequented the clinics. The resulting probability sample consisted of 2,477 women.

Women were eligible for each follow-up survey if they had not been sterilized by the time of the previous survey. Data for the third follow-up were collected by telephone between February and October 2000 (the previous surveys were face-to-face). The average length of time elapsing between the second and third follow-up interviews was 3.5 years. For each wave of data collection, the response rate for eligible (nonsterilized) women was 86% or higher.

The baseline and the first two follow-up surveys focused on women’s contraceptive choices and experiences. The third follow-up survey shifted its focus to investigate a wide range of factors contributing to unintended pregnancy. This third follow-up survey provided the key data for the present paper, including the data for the outcome and relationship variables. The previous rounds did not collect these data in any detail. Where appropriate, we used data from the second follow-up survey as control variables, to ensure that these factors predated the outcome variable and thus could influence the subsequent feelings about childbearing.

For the third follow-up survey, 1,362 women were interviewed (55% of the baseline sample). Of these women, 800 (59%) had at least one pregnancy during the period between the second and third follow-up surveys, and 562 (41%) had no pregnancies.

Questionnaire development

We developed the third follow-up questionnaire to test hypotheses (including those in the present article) generated by our prior qualitative research on unintended pregnancy. In developing the questionnaire, we conducted three rounds of cognitive interviews and a pretest of the questionnaire among low-income women drawn from public clinics similar to the original study sites. We finalized the questionnaire after we concluded that the questions were understood by the women in the ways we intended.

Study partner

For women who had a pregnancy during the follow-up period (pregnancy group), we asked about the partner who fathered their most recent pregnancy. For women who had no pregnancy during the follow-up period (no-pregnancy group), we inquired about the man with whom she had a relationship at the time of the interview. Our preliminary qualitative research showed that because some women did not consider some of their sexual partnerships to have been actual relationships, they were not able to meaningfully answer questions about the characteristics of their relationships with those partners. For this reason, in the survey, we asked women only about the characteristics of their “special relationships,” defined as “a partner, husband or boyfriend with whom you share your life and with whom you have sex. By sex we mean where a man puts his penis in your vagina.” Women were free to interpret what this definition of a special relationship meant to them, and they apparently included a wide range of relationships, as some women included partners they had known only a month or less. Only 94 sexually active women (7% of the total sample) did not identify their partner as a special relationship. We excluded these women from the analysis, as well as 117 women (9%) in the no-pregnancy group who were not currently sexually active and 37 women (3%) from either group because of missing data. The current analysis is based on the remaining 1,114 women.

Measures

Dependent variable

The outcome of interest is how much the woman wanted a baby with her partner at a given point in time. Women were asked with reference to either the 30 days before they got pregnant (pregnancy group) or in the past 30 days (no-pregnancy group): “How much did you want a baby with (name of partner)? Would you say a lot, some, a little, or not at all?” We treated this as a four-category ordinal variable in our analyses.

Independent variables

Independent variables relate to the characteristics of the relationship and the partner. Relationship variables include (a) quality variables – communication with the partner (talking about things that really mattered to the woman), satisfaction with the relationship, and sexual exclusivity of the relationship; (b) variables indicating the degree to which the relationship is established – marital/cohabitation status, duration of the relationship, and how long women expected the relationship to last; (c) previous childbearing – whether the respondent had had a previous baby with her partner; and (d) the woman’s expectations –how much emotional and financial support she expected from her partner if she had a baby with him, how good a father she thought her partner would be, and whether she expected a continued relationship with her partner’s relatives if she had a baby with him, even if her relationship with him ended.

Most of these characteristics refer to the 30 days before the woman became pregnant (pregnancy group) or the 30 days before the interview (no-pregnancy group). Three variables, however, refer to the entire relationship period during which the pregnancy occurred (pregnancy group) or at the time of the interview (no-pregnancy group). (If a woman had an on-and-off relationship with a partner, each uninterrupted stretch of the relationship was treated as a distinct relationship period.) The three variables that refer to the entire relationship period are marital/cohabitation status, satisfaction with the relationship, and sexual exclusivity. Marital/cohabitation status represents whether the woman was married to or cohabiting with her partner at any time during the relationship period. Satisfaction with the relationship and sexual exclusivity refer to during most of the time they were together during the relationship period.

Besides these relationship factors, we also included two other independent variables, which represent the partner’s characteristics: partner’s age and whether he had had any previous children.

Categories of all relationship and partner characteristic variables are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics and Bivariate Relationships Between Independent Variables and How Much Women Wanted a Baby With Partner During a 30-Day Period (N = 1,114)

| Distribution by Independent Variables | How Much Women Want a Baby With Their Partner (%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | A lot | Some | A little | Not at all | |

| Total | 100.0 (1,114) | 24.7 | 19.0 | 16.5 | 39.8 |

| Had a pregnancy during the follow-up period*** | |||||

| Yes | 67.3 (727) | 29.1 | 21.1 | 15.8 | 34.0 |

| No | 32.7 (387) | 15.8 | 14.7 | 17.7 | 51.8 |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

| Age at pregnancy or interview (years)* | |||||

| 14 – 21 | 25.7 (235) | 20.1 | 18.5 | 19.7 | 41.7 |

| 22 – 24 | 23.1 (269) | 28.1 | 21.9 | 15.5 | 34.5 |

| 25 – 29 | 28.9 (359) | 27.2 | 21.4 | 15.7 | 35.7 |

| 30 – 34 | 14.0 (152) | 29.3 | 14.7 | 16.3 | 39.8 |

| 35 or older | 8.3 (99) | 13.7 | 11.3 | 12.1 | 62.9 |

| Race | |||||

| Black | 86.4 (935) | 23.4 | 19.2 | 17.0 | 40.4 |

| White | 13.6 (179) | 33.4 | 17.8 | 12.8 | 36.0 |

| Number of live births at pregnancy or interview** | |||||

| 0 | 16.3 (192) | 31.9 | 18.6 | 20.6 | 28.7 |

| 1 | 37.3 (403) | 26.4 | 22.4 | 16.6 | 34.6 |

| 2 | 25.9 (299) | 23.5 | 19.2 | 14.0 | 43.3 |

| 3 or more | 20.6 (220) | 17.5 | 12.9 | 16.0 | 53.6 |

| Education at previous interview | |||||

| Less than HS | 34.1 (326) | 25.7 | 20.3 | 17.5 | 36.5 |

| HS or GED | 37.2 (428) | 22.5 | 19.5 | 15.3 | 42.6 |

| Vocational | 7.0 (93) | 24.3 | 14.1 | 21.6 | 40.0 |

| Some college or more | 21.7 (267) | 27.2 | 17.6 | 15.0 | 40.1 |

| Worked during previous follow-up period | |||||

| Yes | 84.2 (948) | 23.9 | 19.3 | 17.0 | 39.9 |

| No | 15.8 (166) | 29.3 | 17.6 | 13.7 | 39.5 |

| Poverty: received TANF/AFDC or food stamps during previous follow-up period | |||||

| Yes | 55.7 (588) | 23.0 | 18.4 | 18.1 | 40.5 |

| No | 44.3 (526) | 26.9 | 19.7 | 14.4 | 39.0 |

| Partner characteristics | |||||

| Partner’s age at pregnancy or interview (years)*** | |||||

| 16 – 24 | 29.2 (285) | 20.2 | 20.4 | 19.0 | 40.5 |

| 25 – 29 | 34.7 (401) | 26.8 | 21.2 | 16.6 | 35.4 |

| 30 – 34 | 18.5 (229) | 29.4 | 20.7 | 15.8 | 34.1 |

| 35 or older | 17.5 (199) | 23.4 | 10.4 | 12.6 | 53.6 |

| Partner had any children | |||||

| Yes | 71.1 (798) | 23.2 | 18.6 | 15.4 | 42.7 |

| No | 28.9 (316) | 28.5 | 19.9 | 19.0 | 32.7 |

| Relationship characteristics | |||||

| Relationship quality | |||||

| Communication: How much talk with partner about things that matter to you*** | |||||

| A lot | 60.9 (685) | 30.9 | 19.0 | 16.7 | 33.4 |

| Some | 25.1 (285) | 17.6 | 21.9 | 12.9 | 47.5 |

| A little or none | 14.0 (144) | 10.8 | 13.4 | 21.7 | 54.2 |

| Satisfaction with relationship*** | |||||

| Very satisfied | 42.9 (495) | 32.8 | 21.4 | 14.0 | 31.8 |

| Somewhat satisfied | 46.0 (501) | 20.8 | 17.0 | 17.5 | 44.7 |

| Dissatisfied or very dissatisfied | 11.1 (118) | 10.0 | 17.8 | 21.7 | 50.6 |

| Exclusivity of relationship*** | |||||

| Both exclusive | 76.2 (851) | 28.1 | 19.1 | 16.1 | 36.7 |

| Woman exclusive, man not exclusive | 17.4 (196) | 13.9 | 16.9 | 16.1 | 53.2 |

| Woman not exclusive | 6.4 (67) | 14.4 | 23.1 | 21.4 | 41.2 |

| How established | |||||

| Marriage/cohabitation** | |||||

| Married | 25.9 (316) | 35.8 | 20.2 | 12.1 | 31.8 |

| Cohabiting | 40.9 (440) | 22.8 | 19.0 | 18.0 | 40.3 |

| Noncohabiting | 33.1 (358) | 18.5 | 18.0 | 18.0 | 45.5 |

| Duration of relationship at pregnancy or interview** | |||||

| <6 months | 19.1 (215) | 18.0 | 20.6 | 15.6 | 45.9 |

| 6 – 23 months | 27.1 (294) | 21.3 | 22.9 | 19.9 | 35.9 |

| 2 – 6 years | 30.9 (337) | 29.7 | 18.7 | 15.9 | 35.8 |

| >6 years | 22.9 (268) | 27.9 | 13.4 | 13.8 | 44.9 |

| Expected duration of relationship*** | |||||

| Short | 9.5 (108) | 7.3 | 12.3 | 13.5 | 66.9 |

| Medium | 12.7 (138) | 8.3 | 17.2 | 18.9 | 55.6 |

| Long | 77.8 (268) | 29.6 | 20.1 | 16.4 | 33.9 |

| Previous children with partner | |||||

| Couple had a previous baby | |||||

| Yes | 40.4 (439) | 23.1 | 17.4 | 14.9 | 44.6 |

| No | 59.6 (675) | 25.8 | 20.1 | 17.5 | 36.6 |

| Woman’s expectations | |||||

| How much emotional support expect if get pregnant*** | |||||

| A lot | 54.8 (614) | 31.5 | 19.4 | 18.8 | 30.3 |

| Don’t know | 30.4 (334) | 15.8 | 18.2 | 14.5 | 51.5 |

| Some to none | 14.8 (166) | 18.2 | 18.9 | 11.7 | 51.2 |

| How much financial support expect if get pregnant*** | |||||

| A lot | 64.1 (724) | 31.1 | 19.3 | 18.0 | 31.6 |

| Don’t know | 23.4 (265) | 15.6 | 19.3 | 14.0 | 51.1 |

| Some to none | 12.5 (125) | 9.2 | 16.6 | 13.5 | 60.7 |

| How good a father think partner will be*** | |||||

| Really good | 69.3 (772) | 31.3 | 21.1 | 17.8 | 29.8 |

| Don’t know | 15.6 (177) | 11.9 | 18.9 | 11.2 | 58.0 |

| OK or not good | 15.1 (165) | 7.9 | 9.6 | 15.8 | 66.6 |

| Expect continued close relationship with his relatives if had baby and broke up*** | |||||

| Yes | 67.3 (754) | 29.8 | 19.1 | 16.4 | 34.7 |

| No | 32.7 (360) | 14.4 | 18.9 | 16.5 | 50.3 |

Note: Estimation accounts for complex survey design. Asterisks indicate the statistical significance of the bivariate relationship between independent and outcome variables. HS = high school. GED = General Educational Development degree.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Control variables

We treated all control variables as categorical variables. Control variables include the woman’s age and the number of live births the woman had, either at the time of the pregnancy (pregnancy group) or at the time of the third follow-up interview (no-pregnancy group). Self-reported race was collected at the baseline survey. The remaining control variables were drawn from the second follow-up survey: education completed at the time of that survey, whether the woman worked for pay in the period between the first and second follow-up surveys, and poverty status, as indicated by whether anyone in the household received TANF/AFDC (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families/Aid to Families with Dependent Children) or food stamps in that follow-up period. Categories for these variables are also listed in Table 1.

Data Analysis

We first examined sociodemographic and relationship characteristics of the study women. Second, we examined the bivariate relationship between the control and independent variables and how much the women wanted a baby with their partner. Finally, we estimated ordered logistic regression models (Agresti, 1990) to investigate the effects of relationship variables on how much the women wanted a baby with their partners in the 30-day period, controlling for sociodemographic factors.

As noted earlier, by including both those who did conceive a pregnancy and those who did not, we avoided the bias inherent in restricting the study of fertility desires only to women who have a child. At the same time, we recognize that because of both selectivity and significant differences in the characteristics of the two groups of women, the effects of relationship characteristics on wanting a baby with a partner may differ for the two groups. Because women who got pregnant were more likely to have wanted a pregnancy than women who did not get pregnant, the former were selected for a point in time at which they were more likely to want a baby, whereas the latter were selected for a point in time at which they were less likely to want a baby. In addition, we found in preliminary analysis that the two groups differed on some characteristics: Women in the pregnancy group were generally younger, less educated, and poorer, and their relationships on average were of shorter duration and less likely to be exclusive. They were also less likely to be very satisfied with their relationships or to expect them to last a long time.

For these reasons, we investigated whether the effects of relationship characteristics on women’s desire for a baby with their partner may have differed between the two groups. We estimated a series of ordered logistic regression models in which we tested for an interaction between women’s pregnancy status and each of the independent variables in turn. According to F tests, the only independent variable that had a significant interaction with pregnancy status was satisfaction with the relationship (p = .045). We included this interaction in the final model, along with all control and relationship variables. To describe the interaction, we used the parameter estimates from the final model to compute adjusted odds ratios for satisfaction with the relationship for each of the two pregnancy groups.

Because many of the relationship variables are likely to be highly correlated, we analyzed the eigenvalues of the X′X matrix (Belsley, Kuh, & Welsch, 1980) to determine that multicollinearity was not a problem in the models. We performed all statistical analyses using SUDAAN 8.0.2 to adjust for the complex survey design (Shah, Barnwell, & Bieler, 2003). We applied weights adjusting for the survey design as well as for attrition over the survey rounds.

Results

Descriptive Results

Control variables (sociodemographic characteristics)

Although one fourth of the women were between the ages of 14 and 21 at the time of pregnancy or interview (Table 1, second column), very few were in the lower end of this age bracket: Fewer than 1% of the entire sample were under the age of 18. The majority of women were in their twenties and Black, and the vast majority had children (84% had had at least one live birth). The level of education was relatively low: At the time of the second follow-up, over one third (34%) of the women had not completed high school, 37% had completed high school, and 29% had vocational training or some college education. Most women (84%) worked for pay between the first and second follow-up surveys. More than half lived in poverty: During the previous follow-up period, 56% lived in a household where someone had received welfare support (TANF/AFDC or food stamps).

Independent variables (partner characteristics and relationship characteristics)

The majority of the women’s partners were in their twenties (similar to the women themselves), although they were 3 years older on average than the women (result not shown). Nearly three fourths (71%) had already had at least one child.

Over 60% of the women talked a lot with their partners about things that mattered to them (an indicator of partner communication). Fewer than half (43%) of the women were very satisfied with their relationships, 46% somewhat satisfied, and 11% dissatisfied or very dissatisfied. Three fourths reported that neither they nor their partners were seeing anyone else (exclusive relationships).

During the period of their relationship when the pregnancy was conceived (pregnancy group) or at the time of the interview (no-pregnancy group), 26% of the women were married, 41% cohabiting with their partners, and 33% not cohabiting. One fifth (19%) of the women had been in their relationship for fewer than 6 months; 27% between 6 months and 2 years; and 54% 2 years or more. About three quarters of the women expected their relationship to last a long time.

Fewer than half (41%) of the women had previously had a baby with this partner. Over half (55%) of the women expected a lot of emotional support from their partners if they got pregnant, and somewhat higher proportions thought that their partners would provide a lot of financial support if they got pregnant (64%) and that their partner would be a really good father (69%). About two thirds of the women thought that if they had a baby, they would continue to have a close relationship with their partner’s relatives even if their relationship with their partner ended.

Bivariate associations

Table 1 also summarizes the bivariate relationships between the outcome variable and the control and independent variables (columns 3 – 6). Overall, one fourth of the women in the sample had wanted a baby with their partner in the 30-day period a lot, 19% wanted a baby some, 17% a little, and 40% did not want a baby at all. Compared with women in the no-pregnancy group, women in the pregnancy group were much more likely to say they wanted a baby with their partner a lot and much less likely to say not at all. Among the sociodemographic variables, age and parity had significant associations with women’s desire for a baby with their partner. Women between the ages of 22 and 34 were more likely to want a pregnancy to a greater extent than women who were either younger or older. The more live births women had already had, the less likely they were to want a baby with their partner. Race, education, employment, and poverty status were not significantly associated with wanting a baby with the partner.

Women were more likely to want a baby to a higher degree with their partner if he were between the ages of 25 and 34 than if he were either younger or older. Whether he had already had any children was not significantly related to women’s desire for a baby with him.

All relationship variables except one were significantly associated with wanting a baby with the partner in the direction hypothesized: Women were more likely to want a baby to a higher degree if they were in relationships that were better in quality, more established, and if they had greater or better expectations of their partner or his relatives. The only relationship variable whose bivariate association was not statistically significant was whether the couple had a previous child.

Multivariate Results

Results for the ordered logistic regression model show that when the effects of the relationship factors were taken into account, the two sociodemographic variables (age and parity) with significant bivariate associations continued to have significant effects on how much women had wanted a baby with their partners in the 30-day period (Table 2). Women were less likely to be in the higher categories of wanting a baby more with their partners if they were younger than age 22 or if they had two or more live births. Race, education, employment, and poverty continued to have no significant effect. (Pregnancy status was included in the model, but we do not conceptualize it as a predictor of desire for a baby. Rather, it is included to determine whether the effects of relationship factors differ according to pregnancy group.)

Table 2.

Ordered Logistic Regression Results: Regression Coefficients and Odds Ratios of Wanting a Baby With Partner During a 30-Day Period More Rather Than Less (N = 1,114)

| Variables | β | SE (β) | Odds Ratio (eβ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Had a pregnancy during the follow-up period | |||

| Yes | 1.41 | .25 | 4.1** |

| No (reference) | 0.00 | .00 | 1.0 |

| Sociodemographic factors | |||

| Woman’s age at pregnancy or interview (years) | |||

| 14 – 21 | −0.93 | .29 | 0.4** |

| 22 – 24 | −0.14 | .19 | 0.9 |

| 25 – 29 (reference) | 0.00 | .00 | 1.0 |

| 30 – 34 | 0.09 | .22 | 1.1 |

| 35 or older | −0.62 | .35 | 0.5 |

| Number of live births at pregnancy or interview | |||

| None (reference) | 0.00 | .00 | 1.0 |

| 1 | −0.40 | .22 | 0.7 |

| 2 | −0.94 | .26 | 0.4*** |

| 3 or more | −1.43 | .33 | 0.2*** |

| Relationship factors | |||

| Relationship quality | |||

| Satisfaction with relationship | |||

| Very satisfied (reference) | 0.00 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Somewhat satisfied | −0.15 | .26 | 0.86 |

| Dissatisfied or very dissatisfied | 1.05 | .42 | 2.86* |

| Satisfaction × pregnancy | |||

| Very satisfied and had pregnancy (reference) | 0.00 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Somewhat satisfied and had pregnancy | −0.06 | .33 | 0.94 |

| Dissatisfied or very dissatisfied and had pregnancy | −1.20 | .51 | 0.30* |

| How established | |||

| Marriage/cohabitation status | |||

| Married (reference) | 0.00 | .00 | 1.0 |

| Cohabiting | −0.38 | .20 | 0.7 |

| Noncohabiting | −0.58 | .22 | 0.6** |

| Expected duration of relationship | |||

| Short | −0.91 | .25 | 0.4** |

| Medium | −0.58 | .23 | 0.6* |

| Long (reference) | 0.00 | .00 | 1.0 |

| Previous children | |||

| Couple had a previous baby | |||

| Yes | −0.61 | .18 | 0.5*** |

| No (reference) | 0.00 | .00 | 1.0 |

| Woman’s expectations | |||

| How good a father she thought he would be | |||

| Really good (reference) | 0.00 | .00 | 1.0 |

| Don’t know | −0.66 | .24 | 0.5*** |

| OK or not very good | −0.83 | .22 | 0.4** |

| Expect continued close relationship with his relatives if had baby and broke up | |||

| Yes | 0.43 | .16 | 1.5** |

| No (reference) | 0.00 | .00 | 1.0 |

Note: Estimation accounts for complex survey design. This model also included race, education, work, poverty, partner’s age, whether partner had had any previous children, communication, exclusivity in the relationship, expected emotional support, and expected financial support. None of these variables had a significant effect at the .05 level as indicated by F tests. Ordered logistic regression estimates a single odds ratio that summarizes the association of interest across all levels of the outcome. In this case, the odds ratio is a summary of the odds of three dichotomous comparisons: the probability that women want a baby (1) a lot versus some, a little, or none; (2) a lot or some versus a little or none; and (3) a lot, some, or a little versus none.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

When the effects of the other factors were controlled, the single partner characteristic with a significant bivariate association (partner’s age) and five of the relationship variables with significant bivariate associations (communication, sexual exclusivity, relationship duration, expectation of emotional support, and expectation of financial support) no longer had any significant effect on how much women wanted a baby with their partners in the 30-day period. All of the other relationship variables did have significant effects in the model. Taking into account the effects of all other factors in the model, women were more likely to want a baby with their partner to a greater extent if they were married or cohabiting, expected the relationship to last a long time, did not have a previous baby with their partner, thought their partner would be a really good father, or expected a continued close relationship with their partner’s relatives if they had a baby with him even if the relationship ended.

Whether women had a previous baby with their partners was significant in the multivariate but not in the bivariate analysis. This finding can be explained by the fact that having had a previous baby is positively associated both with marriage and with relationship duration, and both are associated with an increased likelihood that women want a baby with their partner. Therefore, the relationship between having a previous baby and wanting a baby does not become significant until marriage/cohabitation and relationship duration are controlled (analysis not shown).

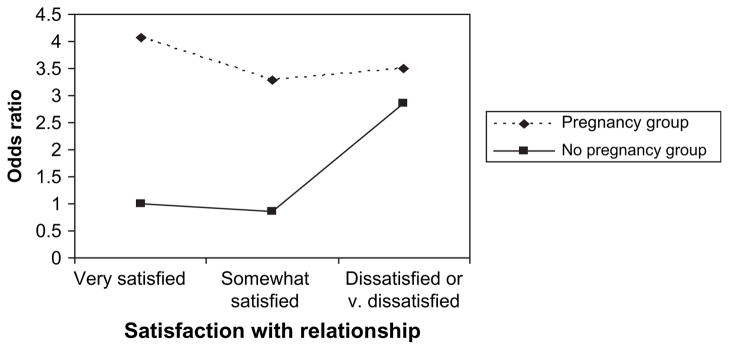

The effects of satisfaction with the relationship depended on pregnancy status (interaction significant at p = .045). This interaction effect is illustrated in Figure 1. Among women in the pregnancy group, satisfaction with the relationship had little effect on women’s desire for a baby with their partner. Among women in the no-pregnancy group, however, those who were dissatisfied with their relationship were much more likely to want a baby with their partner to a higher degree than those who were very satisfied (odds ratio of 2.9). This was an unexpected finding, and we considered several possibilities to explain it.

Figure 1.

Interaction of Satisfaction with the Relationship with Pregnancy Status in Its Effect on How much Women Wanted a Baby with their Partner During a 30-Day Period, Estimated from Ordered Logistic Regression Models

We considered that women who were dissatisfied with their relationships might have wanted to have a baby to improve their relationship. In answer to questions about their thinking during the 12 months before the interview, however, none of the dissatisfied women in the no-pregnancy group said that they had thought about “having a baby to bring you and your partner closer.” Another possible explanation was that women who wanted a baby and did not have one were dissatisfied with their relationships for that reason. Although we have limited evidence, we did find that dissatisfied women in the no-pregnancy group were no more likely than satisfied women to report that it was harder for them to get pregnant “compared to most women” (data not shown). A third possible explanation was that women who wanted a child may have stayed in a relationship they were dissatisfied with, just so they could have a child. The majority of these women, however, had already had at least one baby with this partner (58%), and 83% had had at least one child (either with this partner or another).

A fourth possible explanation was that these women may have wanted a baby to provide emotional connection. Unlike women in the pregnancy group, women in the no-pregnancy group who were dissatisfied with their relationships were significantly more likely than women who were very or somewhat satisfied to report that they thought about “having a child to love and care for” during the 12 months before the interview.

Discussion

This paper sought to investigate a hitherto neglected research question: the influence of relationship characteristics and women’s expectations of their sexual partner at a given point in time on their desire to have a child with him at that time. We stated four hypotheses about these effects, three of which were largely supported by the results of the multivariate analysis.

Hypothesis 1 (Quality of Relationships)

Hypothesis 1 was not supported. The measures used to reflect relationship quality (communication with the partner, sexual exclusivity, and, among women in the pregnancy group, satisfaction with the relationship) had no significant effect on women’s desire for a baby with the partner when other factors were controlled. This finding is unexpected and may be related to the fact that the women lived in an environment of extreme relationship instability. In our preliminary qualitative research, many of the women had the experience of bearing children with men in relationships that did not last, and in the present study, one third of the women who had a pregnancy during the follow-up period were no longer in a special relationship with the man who was the father by the time of the interview. In this context, the quality of a relationship that might not last long may not be a very relevant consideration in women’s feelings about bearing children with the partner. Additional research among women who live in an environment of greater relationship stability should determine the nature of the association between the quality of the relationship and women’s desire for a baby with their partner.

The one quality variable that did have a significant effect (among women in the no-pregnancy group) had the opposite effect to what was hypothesized. Women who were dissatisfied with their relationship were more likely to have wanted to have a baby with their partner in the 30-day period than women who were satisfied, controlling for other factors. Although the number of women in the no-pregnancy group who were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with their relationships was relatively small (n = 24), the effect was nonetheless significant. We did not find any clear evidence to support three of the possible explanations we advanced (that women who were dissatisfied with their relationship wanted a baby to bring their partner closer, that the fact that they did not have a baby was the reason they were dissatisfied with the relationship, or that they stayed in a relationship they were dissatisfied with because they wanted to have a baby), although we had little data on these issues. A fourth possible explanation did receive some support, however, namely, that these women wanted a baby to fulfill a need for emotional connection.

Hypothesis 2 (How Established Relationships Were)

Hypothesis 2 was mostly supported: Women who were married or cohabiting and those who expected their relationships to last a long time were more likely to want a baby with their partner to a higher degree in the 30-day period. The only stability variable that did not have a significant effect was relationship duration. The finding regarding the importance of marriage/cohabitation status is consistent with other research showing marital status to be a key factor in childbearing and fertility desires (Bachu & O’Connell, 2001; Zabin et al., 2000).

Hypothesis 3 (Previous Children)

The hypothesis that women would be more likely to want a baby with their partner if the couple had not had a previous baby together was supported. In contrast, the results did not support the hypothesis that women would be more likely to want a baby if their partner did not already have one (with anybody). Women therefore appeared to be more motivated to have a baby with their partner by their desire to have a child together, rather than by the desire to give their partner a child if he did not have one. This finding contrasts with findings by Stewart (2002). The difference may reflect at least in part differences in study samples, because the sample for Stewart’s study was of a higher socioeconomic level and all were married.

Hypothesis 4 (Woman’s Expectations)

The hypothesis that women who had positive expectations of their partner and his family (if they were to have a baby) would be more likely to want a baby with him was supported in part. All of the variables related to expectations of support and the partner being a good father had a significant association with wanting a baby with the partner in bivariate analysis. In the multivariate analysis, however, the only variables that had significant effects were how good a father he would be and expecting to continue to have a relationship with his relatives. Expected emotional and financial support from the partner no longer had a significant effect when all of the other variables in the model were taken into account.

The finding that expected financial and emotional support did not significantly affect women’s desire for a baby with their partner in multivariate analysis was unexpected. Further analysis showed that these measures had significant effects in the model if the model did not include the variable indicating how good a father the partner would be. Thus, it may be that, for the study women, providing financial and emotional support was part of being a good father or perhaps was not as important as the overarching quality of being a good father.

Interestingly, the research literature on women’s desire for a child has apparently not addressed the importance of women’s perception of her partner as being a good father. Its centrality to women is illustrated by the following quotes from answers to an open-ended question in the survey asking for the “big picture” surrounding an unintended pregnancy: “It didn’t matter one way or the other [if I got pregnant] because I was with him and he was a good daddy” and “I knew that if I did [get pregnant] it couldn’t be with a better father.”

Given that the majority of the women in our sample were Black, the importance of a continued relationship with the partner’s relatives may reflect the prevalence of extended kinship support networks among Black American families documented by numerous researchers (e.g., Aschenbrenner, 1973; Stack, 1974; Sudarkasa, 1988). The women in our sample may have given more weight to continued support from the partner’s relatives, because they perceived it to be possibly more solid and permanent than emotional and financial support from the partner, who may leave the relationship.

Limitations

Because women who had a pregnancy were asked retrospectively about the characteristics of their relationships and about how much they wanted to have a baby with their partner in the 30 days before they got pregnant, their responses are subject to recall bias. Although recall bias has generally been found to inflate the proportion of women who report their pregnancies as intended (Sable, 1999), it may actually depress the proportion of women who say they wanted a baby with their partner if the relationship deteriorated or ended between conception and the time of the interview.

Some limitations also relate to the generalizability of the study findings. Although women with a wide range of relationships were included in the study, we did not include a relatively small number of women who had sexual partnerships that they did not consider a special relationship, as we defined it in the survey. In addition, the study sample is not nationally representative. The study sample enrolled at baseline was a probability sample of women who were choosing a contraceptive method in public family planning and postpartum clinics and maternity wards in two southeastern cities. Most of the women were low income and most were Black (86%). Although these characteristics of the sample limit its generalizability, they make it particularly well suited for investigating relationship factors influencing childbearing desires among a group of women who frequently have unstable non-marital unions and bear children within these relationships.

Despite these limitations, the findings about the effect of women’s relationship characteristics –including the degree to which relationships are well established, women’s assessment of their partner’s ability to be a good father, and their expectations of support from his family – on their desire for a baby are broadly consistent with the research literature. This consistency suggests that the research reported here may apply to other populations at high risk of unintended pregnancy and unstable relationships.

Conclusions

Including both women who did and did not have a pregnancy in our analyses (in contrast to much research that is based only on women who had a pregnancy) allowed us to gain a more complete and less biased picture of the childbearing desires of women overall. We found that, despite significant differences in the characteristics of the two groups, the effects of relationship characteristics and expectations are largely the same for the two groups, underlining the fundamental importance of the relationship context on women’s desires to have children with a particular partner at a particular time.

The findings from this paper enhance our understanding of how the relationship context leads some women not to want a baby with their partner at a given point in time and thus to be vulnerable to having an unintended pregnancy. We found that it is insufficient to consider only women’s individual characteristics in investigating their childbearing desires. Individual women’s lives are embedded in an environment that includes most critically, where childbearing is concerned, their relationship with a male partner. We found that women’s relationships with and expectations of their partner significantly affected their feelings about having a baby with him. In general, as we anticipated, we found that women who were in more established relationships, who had not had a child with their partner, and who had positive expectations of him as a father were more likely to want a baby with their partner. An unexpected finding, however, was that women in higher quality relationships (as represented by measures of communication, sexual exclusivity, and satisfaction with the relationship) were no more likely to want a baby with their partner than were women with lower quality relationships. It may be that for a population experiencing many unstable and nonmarital relationships, the quality of relationships is not a pragmatic criterion for wanting a child, whereas the ability of the partner to be a good father and the enduring qualities of the relationship are highly practical considerations.

This article focuses on women’s desire to have a baby with a partner in a 30-day period. One can expect that the relationship context would also affect the degree to which women act on their desire to have a baby or not to have a baby with the partner, that is, women’s actual contraceptive and childbearing behavior. Thus, we encourage researchers exploring fertility desires, childbearing, and unintended pregnancy to collect and analyze a variety of measures related to qualities and expectations of relationships with sexual partners.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this article was funded by Grant RO1 –HD34897 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Helen P. Koo as principal investigator. The authors gratefully acknowledge the roles of Tzy-Mey Kuo, who provided significant statistical and programming support; C. M. Suchindran, who provided thoughtful analytical advice throughout the study; the anonymous reviewers who provided valuable suggestions to improve the article; William L. Graves and Sherry Laurent, who served as on-site investigators in Atlanta and Charlotte; and the interviewers and respondents who participated in the survey.

References

- Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. New York: Wiley; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Aschenbrenner J. Extended families among Black Americans. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1973;4:257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Bachu A, O’Connell M. Current Population Reports, P20-543RV. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2001. Fertility of American women: June 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE. Regression diagnostics. New York: Wiley; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett MD, Mosher WD. Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Statistics. 2002;23(22):1–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass LL. What’s happening to the family? Interactions between demographic and institutional change. Demography. 1991;27:483–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs B. Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2002. Fertility of American women: June 2002; pp. 20–548. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll AK, Hearn GK, Evans VJ, Moore K, Sugland BW, Call V. Nonmarital child-bearing among adult women. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;61:178–187. [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Kefalas M. Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006;38:90–96. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer RC, Stanford JB, Jameson P, DeWitt MJ. Exploring the concepts of intended, planned and wanted pregnancy. Journal of Family Practice. 1999;48:117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest JD. Epidemiology of unintended pregnancy and contraceptive use. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;170:1485–1488. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)05008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D, Hechter M, Kanazawa S. A theory of the value of children. Demography. 1994;31:375–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider FK, Kaufman G. Fertility and commitment: Bringing men back in. Population and Development Review. 1996;22:87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman LW, Manis JD. The value of children in the United States: A new approach to the study of fertility. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1979;41:583–596. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Eisenberg L, editors. Institute of Medicine. The best intentions: Unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, DC: The National Academy Press; 1995. Available at http://books.nap.edu/catalog/4903.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall C, Afable-Munsuz A, Speizer I, Avery A, Schmidt N, Santelli J. Understanding pregnancy in a population of inner-city women in New Orleans – results of qualitative research. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60:297–311. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo HP, Woodsong C, Shedlin M. From unintended to unintentionally planned: Exploring subintended pregnancies. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America; New York. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Luker KC. A reminder that human behavior frequently refuses to conform to models created by researchers. Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;31:248–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Munson ML. Births: Final data for 2002. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2003;52(10) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers SM. Marital uncertainty and child-bearing. Social Forces. 1997;75:1271. [Google Scholar]

- Sable MR. Pregnancy intentions may not be a useful measure for research on maternal and child health outcomes. Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;31:246–247. 260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Bieler G. SUDAAN’s user’s manual: Software for analysis of correlated data (Release 8.0.2) Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stack CB. All our kin: Strategies for survival in a Black community. New York: Harper & Row; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SD. The effect of stepchildren on childbearing intentions and births. Demography. 2002;39:181–197. doi: 10.1353/dem.2002.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarkasa N. Interpreting the African heritage in Afro-American family organization. In: McAdoo HP, editor. Black families. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A. Marital dissolution, remarriage, and childbearing. Demography. 1978;15:361–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Danella RD, Rogers SM. Sexual behavior in the United States, 1930–1990: Trends and methodological problems. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1995;22:173–190. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199505000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westoff L. The second time around: Remarriage in America. New York: Viking Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Zabin LS, Huggins GR, Emerson MR, Cullins VE. Partner effects on a woman’s intention to conceive: ‘Not with this partner’. Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;32:39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]