Abstract

The serine protease autotransporters of Enterobacteriaceae (SPATEs) are secreted by pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria through the autotransporter pathway. We previously classified SPATE proteins into two classes: cytotoxic (class 1) and noncytotoxic (class 2). Here, we show that Pic, a class 2 SPATE protein produced by Shigella flexneri 2a, uropathogenic and enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strains, targets a broad range of human leukocyte adhesion proteins. Substrate specificity was restricted to glycoproteins rich in O-linked glycans, including CD43, CD44, CD45, CD93, CD162 (PSGL-1; P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1), and the surface-attached chemokine fractalkine, all implicated in leukocyte trafficking, migration, and inflammation. N-terminal sequencing of proteolytic products revealed Pic (protease involved in colonization) cleavage sites to occur before Thr or Ser residues. The purified carbohydrate sLewis-X implied in inflammation and malignancy inhibited cleavage of PSGL-1 by Pic. Exposure of human leukocytes to purified Pic resulted in polymorphonuclear cell activation, but impaired chemotaxis and transmigration; Pic-treated T cells underwent programmed cell death. We also show that the Pic-related protease Tsh/Hbp, implicated in extraintestinal infections, exhibited a spectrum of substrates similar to those cleaved by Pic. In the guinea pig keratoconjunctivitis model, a Shigella pic mutant induced greater inflammation than its parent strain. We suggest that the class-2 SPATEs represent unique immune-modulating bacterial virulence factors.

Keywords: glycoprotease, diarrhea

Among the most important enteric pathogens worldwide are Shigella spp. and pathogenic Escherichia coli (1, 2), yet vaccines for these agents are not available. One impediment to such vaccine efforts is the fact that enteric pathogens modulate the host immune system to promote and prolong infection. Thus, understanding the impact of enteric pathogens on the human immune system is a high research priority.

We first described a family of putative virulence factors called the serine protease autotransporters of Enterobacteriaceae (SPATEs), secreted by all pathogenic E. coli and Shigella spp. (3, 4). This family now numbers more than 20 proteases, with diverse functions. We have proposed that SPATEs can be divided phylogenetically into two distinct classes, designated 1 and 2 (5). Class 1 SPATEs are cytotoxic in vitro and induce mucosal damage on intestinal explants. Although the actions of class 1 SPATEs are not fully understood, several have been shown to enter eukaryotic cells and to cleave cytoskeletal proteins (6–8). More enigmatic are the class 2 SPATEs, which include (i) the thermostable hemagglutinin (Tsh) from avian pathogenic E. coli, and its nearly identical homolog, hemoglobin-binding protein (Hbp) from human extraintestinal E. coli (9, 10); (ii) the Pic protease (protease involved in colonization), found in Shigella flexneri, enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), and uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) (11–13); and (iii) the EpeA (EHEC-plasmid encoded autotransporter) from enterohemorrhagic E. coli (14). Pic protease induces mucus release, cleaves mucin, and confers a subtle competitive advantage in mucosal colonization (11, 15, 16). However, the fact that not all producers of the class 2 SPATEs are mucosal pathogens suggested to us that cleavage of mucin-family substrates may provide an additional advantage to the pathogen (17, 18).

A variety of leukocyte surface glycoproteins with vital roles in numerous cellular functions are substituted with carbohydrates structurally similar to those found on human mucin glycoproteins (19, 20). Here, we show that the substrates of mucin-active class 2 SPATEs include glycoproteins located on the surface of nearly all lineages of hematopoietic cells. These targets, including CD43, CD44, CD45, CD93, fractalkine, and PSGL-1 (P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1), may have diverse effects on the immune response, including leukocyte apoptosis, activation, migration, and signaling. Our data suggest broadly important mechanisms for these common virulence factors.

Results

Mucinase Activity of S. flexneri and Potential Targets on Human Muc Proteins.

We reported previously that Pic cleaves ovomucin and bovine submaxillarly mucin (BSM). After overnight incubation, supernatants of S. flexneri 2a cause near complete degradation of the major mucin species (Fig. S1A). N-terminal sequencing of mucin breakdown products over time (Fig. S1B) revealed the first eight amino acids of the major breakdown fragments to be SETNAIIG; this motif corresponded to residues S588 and following on the 462-kDa BSM glycoprotein (Bos Taurus, XP_002687422.1). BLAST analysis of the predicted Pic target revealed 100% identity with sequences encoding the human Muc19 protein (XP_002344701.1), the 1,184-kDa apomucin protein (NP_001106757.1), the Equinus submaxillary apomucin (XP_001915445.1), and two more human hypothetical mucin proteins (XP_002343203.1, XP_002347351.1). Interestingly, sequences similar to SETNAIIG were found within a large number of other human Muc and Muc-related proteins, suggesting the possibility that the Pic substrate profile may be broader than we had supposed.

Cleavage of Sialomucin (CD43) on Human Leukocytes by Pic-Producing Pathogenic Strains.

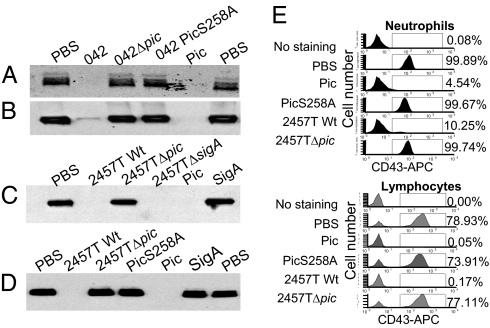

Among the mammalian Muc-related proteins are a large number of extracellular and membrane-associated glycoproteins. To determine whether Pic cleaved such proteins, we first addressed CD43, also known as sialomucin, a major cell-surface glycoprotein expressed on nearly all lineages of hematopoietic cells. Human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) isolated from blood samples of healthy adult volunteers were treated with purified Pic or with the supernatants of EAEC strain 042; for comparison, cells were treated with supernatants of a previously described isogenic null pic mutant, or with supernatants of 042PicS258A, which expresses Pic harboring a single amino acid mutation at the catalytic serine (Fig. 1 A and B). CD43 was completely degraded by Pic on both PMNs and PBMCs, as ascertained by Western immunoblot. Similar results were obtained using the supernatants of wild-type S. flexneri 2457T (Fig. 1 C and D).

Fig. 1.

Cleavage of sialomucin (CD43) on human leukocytes by Pic. PMNs (A, C, and E) and PBMCs (B, D, and E) were isolated from healthy volunteers and treated with log-phase supernatants from the following strains: EAEC 042, an isogenic EAEC042Δpic mutant, or the protease deficient EAEC042PicS258A strain; controls comprised 2 μM of purified Pic protein or PBS (A and B). Cells were alternatively treated with supernatants of S. flexneri 2457T, an isogenic Pic mutant, an isogenic SigA null mutant strain, or with 2 μM of purified Pic, PicS258A, or SigA (C and D). Following 30-min incubation at 37 °C, samples were analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by immunoblot (A–D) or flow cytometry (E) using an Hrp- or APC-conjugated monoclonal antibody specific to the extracellular domain of human CD43. PBMC were gated by low side scatter, and PMNs were gated under high side scatter. Flow cytometry data are representative of at least four independent experiments.

In addition to Pic, S. flexneri 2457T secretes two other SPATE proteins: SepA and SigA. Neither supernatants containing SepA nor purified SigA induced degradation of CD43, suggesting that the effect is specific for Pic (Fig. 1 C and D).

To confirm that Pic cleaves extracellular CD43 on intact leukocytes, we performed flow cytometry analyses of human PMNs or PBMCs treated with purified Pic, PicS258A, or supernatants of S. flexneri. Staining with anti-CD16 (for PMNs), anti-CD3 (for lymphocytes), and anti-CD43–conjugated mAbs revealed that only CD43 was cleaved, becoming undetectable on the surfaces of neutrophils and lymphocytes after treatment with purified Pic or Shigella supernatants, but CD43 was present on cells treated with purified PicS258A (Fig. 1E).

Pic Cleaves a Broad Array of O-Glycosylated Mucin-Like Proteins.

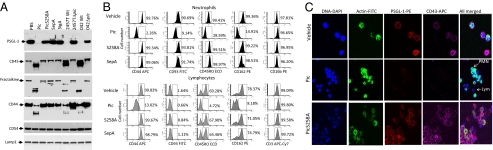

We also found that Pic cleaved other mucin type O-glycans involved in diverse functions of the immune system, including PSGL-1, CD44, CD45, CD93, and fractalkine/CX3CL1 (Fig. 2A). None of the purified proteins or bacterial supernatants cleaved recombinant intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) (CD54) or lamp-1 proteins (Fig. 2A). We treated human neutrophils and lymphocytes with purified SPATE proteins and S. flexneri supernatants, and analyzed the presence of the various targets by flow cytometry and confocal microscopy, using mAbs that recognize the extracellular domains of each molecule. All molecules that were susceptible to cleavage in recombinant form were also degraded from the surfaces of both human neutrophils and lymphocytes (Fig. 2 B and C). Shigella supernatants cleaved the extracellular domains of PSGL-1, CD45, CD93, and CD43 (Fig. S2), whereas CD3 and CD16 were not affected (Fig. 2B). The heavily O-glycosylated protein CD93, which is present on neutrophils but not on lymphocytes, was also degraded by Pic (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Cleavage of an O-glycosylated mucin-like protein family by Pic. (A) Five micrograms of glycosylated human recombinant proteins were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with supernatants of S. flexneri 2457T, EAEC 042, the isogenic S. flexneriΔpic and EAEC042Δpic mutant strains, or with 2 μM of purified Pic, PicS258A, SepA, or SigA. Samples were analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by immunoblot using monoclonal antibodies to the external domain of PSGL-1, CD45, CD44, and fractalkine. Control proteins included ICAM-1 (CD54) and LAMP-1. (B) Pic protein degrades the extracellular domain of O-glycosylated mucin-like proteins on human leukocytes. The 1 × 106 PMNs or PBMCs were isolated from human blood and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min with 2 μM of purified Pic, PicS258A, or SepA and analyzed by flow cytometry using monoclonal antibodies against the extracellular domains of CD44, CD45, PSGL-1, CD93, CD3, or CD16. Lymphocytes were gated by low side scatter using anti-CD3, but neutrophils were gated under high side scatter and anti-CD16 binding. Flow cytometry data are representative of at least four independent experiments. (C) To visualize degradation of mucin-like proteins, Pic-treated whole-blood leukocytes were stained for DNA, actin, CD43, and PSGL-1, followed by fluorescence microscopy. Arrows indicate PMNs and lymphocytes by virtue of nucleus and cytoplasm shape.

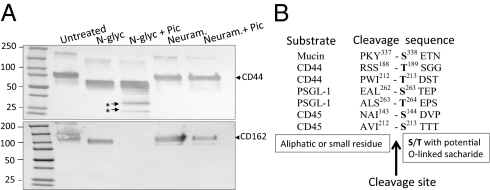

Pic Recognizes O-, but Not N-Glycosylated Glycans.

To ascertain the relevance of carbohydrate substitution in Pic substrate recognition, we used human recombinant CD44 and PSGL-1, which are known to harbor both N- and O-linked oligosaccharides. We found that pretreatment of the glycans with neuraminidase, which removes both N- and O-linked oligosaccharides, prevented degradation of both glycoproteins, implicating carbohydrates in substrate recognition (Fig. 3A). In contrast, removing N-linked saccharides with N-glycosidase-F did not protect CD44 or PSGL-1 from degradation by Pic (Fig. 3A). Moreover, Pic was not able to degrade the heavily N-linked glycosylated proteins E-, P- or L-selectins, nor macrophage-1 (MAC-1) integrin (Fig. S3).

Fig. 3.

Proteolytic activity of Pic is dependent on O-, but not on N-glycosylation. (A) Five micrograms of recombinant CD44 or PSGL-1 proteins were de-glycosylated with neuraminidase or N-glycosydase-F at 37 °C overnight; deglycosylated proteins were then incubated with 2 μM of Pic at 37 °C for 1 h. Samples were analyzed by Western immunoblot using an anti-CD44 or anti-PSGL-1 antibodies. (B) Amino acid sequences flanking cleavage sites in four Pic substrates are shown. Asterisks indicate degraded products analyzed by N-terminal sequencing.

To assess the Pic cleavage site, we treated recombinant PSGL-1, CD44, and CD45 with purified Pic and characterized the dominant early degradation products by N-terminal sequencing (Fig. S3B). In all cases, Pic cleaved before a serine or threonine residue (Fig. 3B and Fig. S3C). Most of the putative cleavage sites occurred between Ser/Thr and aliphatic (I, V, L) or small amino acids (A, V, S, T).

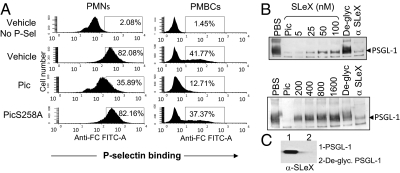

Inhibition of P-Selectin Binding to Human Leukocytes by Pic.

To address the functional significance of Pic, we treated human neutrophils and lymphocytes with purified Pic, PicS258A, or PBS vehicle control for 30 min, followed by incubation with human P-selectin-IgG chimera. Binding of P-selectin chimera to leukocytes was evaluated by flow cytometry using a FITC-conjugated antihuman Fc antibody. We observed the expected interaction between P-selectin and untreated PMNs or PBMCs (Fig. 4A); however, cells treated with purified Pic exhibited diminished interaction with P-selectin. Rolling interactions between leukocytes and the endothelium are mediated by selectin–PSGL-1 interaction, and require branched Sialyl Lewis-X (SLeX)–O-glycan extensions on specific PSGL-1 amino acid residues. To evaluate whether SLeX saccharide was affected by Pic treatment, we stained human neutrophils with FITC-conjugated anti-SLeX monoclonal antibody. As shown in Fig. S4, SLeX was found on more than 90% of the untreated neutrophils, or on cells treated with PicS258A or SepA. However, the cell population bearing the SLeX carbohydrate was reduced by almost 35% following treatment with purified Pic, compared with untreated cells (Fig. S4). Interestingly, increasing concentrations of synthetic SLeX carbohydrate (5 nM to 1.6 μM) preincubated with Pic protein before treatment of the recombinant PSGL-1 protein engendered dose-dependent inhibition of Pic protease activity on PSGL-1 (Fig. 4B). We confirmed that the recombinant PSGL-1 used in the cleavage assays bear SLeX (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of P-selectin binding to human leukocyte by Pic. (A) 1 × 106 human lymphocytes were treated with 2 μM purified Pic or PicS258A, or with PBS control for 30 min followed for 30-min incubation with human P-selectin-IgG chimera. Binding of P-selectin chimera to leukocytes was evaluated by flow cytometry using a FITC-conjugated anti human Fc antibody. Untreated cells without incubation with P-selectin chimera (No P-Sel) were also stained with antihuman Fc antibody. (B) Inhibition of Pic protease activity by SLeX carbohydrate was evaluated by Western blot using 5 μg of recombinant PSGL-1 and 2 μM of Pic previously incubated with twofold increasing concentration of SLeX carbohydrate (5–1,600 nM). PSGL-1 or PSGL-1 deglycosylated by neuraminidase treatment (De-glyc) were incubated with Pic as controls. PBS, untreated PSGL-1; α-SLeX, PSGL-1 previously incubated with an anti-SLeX antibody before treatment with Pic. Western blot was developed with an anti PSGL-1 monoclonal antibody. (C) SLeX saccharide on PSGL-1 and deglycosylated PSGL-1 were analyzed by Western blot using a monoclonal antibody against SLeX.

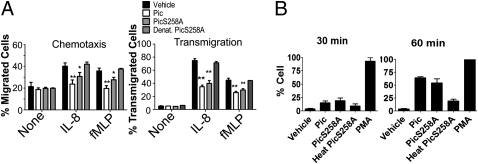

Pic Impairs PMN Chemotaxis and Transmigration.

We also assessed the effects of Pic on PMN function using in vitro chemotaxis assays. Calcein-labeled PMNs incubated with Pic, PicS258A, or PBS vehicle control were applied to 3-μM pore transwell membranes and stimulated with IL-8 or fMLP (N-formyl-methionine-leucine-phenylalanine) as chemoattractants; after 4 h incubation, the neutrophils that had transmigrated toward the chemoattractant were enumerated. We observed ∼20% translocation of untreated PMNs in this model (Fig. 5A), compared with only <2% PMN migration when the PMNs were treated with Pic protease (Fig. 5A) (P < 0.01). Unexpectedly, the movement of PMNs incubated with PicS258A was significantly reduced compared with buffer alone as negative control (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5A); denaturation of PicS258A by heating completely abolished its effects (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Impairment of PMN chemotaxis and transmigration through endothelial cell monolayers by Pic. (A) Chemotaxis: 3 × 105 calcein-AM labeled PMNs were treated with 2 μM of Pic, PicS258A, or PBS vehicle control in the upper chamber of Fbg-coated transwell inserts; 100 mM of IL-8 or 100 nM of fMLP were added to the lower chamber. Penetration of cells through the membrane was measured after 4 h fluorometrically. Transmigration: PMNs preincubated as above were applied to the upper chamber of inserts supporting HBMVEC-L, and transmigrated PMNs were enumerated as mentioned before. Data shown are means and SEM of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate; dates were combined and analyzed by one-way ANOVA. The numbers of migrated cells were normalized to vehicle control with chemoattractant (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05). (B) Activation of neutrophil oxidative burst by Pic: 1 × 106 human neutrophils were labeled with dihydrorhodamine-123 dye for 5 min, immediately treated with 2 μM of LPS-free purified Pic, PicS258A, heat-denatured PicS258A, or PBS vehicle control, and analyzed by flow cytometry for oxidative burst, indicated by FITC fluorescence at 30- and 60-min time points. For positive control, 100 ng/mL of PMA was used. The cell population was gated to distinguish vehicle-treated and PMA-treated controls. Flow cytometry data are representative of three independent experiments.

To addressed the potential effect of Pic on PMN transmigration through endothelial cell monolayers, calcein-labeled PMNs were treated with Pic and added to human lung microvascular endothelial cells (HBMVEC-L) monolayers cultured in transwells, and stimulated with IL-8 and fMLP as chemoatractants. Nearly 65% and 40% of untreated neutrophils transmigrated in the presence of IL-8 and fMLP, respectively (Fig. 5A). In contrast, transmigration of cells treated with Pic protease in the presence of IL-8 or fMLP was ∼31% and 21%, respectively (both P < 0.01) (Fig. 5A). We observed a 1.5-fold reduction of PMN transmigration when the leukocytes were incubated with PicS258A compared with untreated cells (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5A); this effect was abolished by heat-treatment of the protease (Fig. 5A). Taken together, these data suggest that interaction of Pic with O-glycoproteins directly impairs PMN function.

Activation of the Neutrophil Oxidative Burst by Pic.

The neutrophil oxidative burst is also induced by stimulation of glycoproteins at the plasma membrane (21). We found that LPS-free Pic at 2 μM (the minimal concentration required for depletion of more than 90% of O-glycoproteins in a 1-h period) (Fig. S5) triggered the respiratory burst in at least 10% to 15% of PMNs after 30-min incubation, and in more than 50% of cells after 60 min (Fig. 5B and Fig. S6). The protease mutant PicS258A activated the oxidative burst to the same degree as Pic (Fig. 5B and Fig. S6), whereas heat-treatment of PicS258A abolished this effect (Fig. 5B and Fig. S6), further ruling out an effect of contaminating heat-stable LPS.

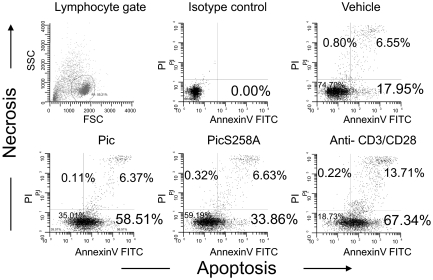

Pic Induces Apoptosis of Activated T Cells.

Cross-linking of PSGL-1, CD43, CD44, CD45, and CD99 on activated T cells induces apoptosis (22–25). To determine whether Pic binding or cleavage of O-glycans on activated T cells induces apoptosis, we isolated lymphocytes from healthy volunteers and activated the cells with ConA, then treated the cells with Pic; cells were stained with annexin V or propidium iodide (PI), to detect apoptosis or necrosis, respectively. More than 50% of cells treated with Pic underwent apoptosis in these experiments, which was comparable to the levels induced by cross-linking of CD3 and CD28 with specific mAbs (Fig. 6). Cells treated with PicS258A exhibited reduced levels of apoptosis compared with those treated with active Pic; however, the proportion of apoptotic cells was approximately twofold higher than that observed in untreated cells (Fig. 6). Necrosis was apparent in all treatments, but exclusively after onset of apoptosis (Annexin-V/PI double staining). Apoptosis phenomenon was also confirmed by detecting fragmented DNA in Tunel assays (Fig. S7).

Fig. 6.

Pic triggers cell death of activated human T cells. Activated human T lymphocytes on day 5 after stimulation with ConA (2 μg/mL) were incubated with 2 μM of purified Pic, PicS258A, or control anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies overnight. Following double staining with annexin-V FITC and PI, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the percentage of dead cells. Without gating, 10% of 10,000 total events were displayed. Flow cytometry data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Effect of Pic in the Guinea Pig Keratoconjunctivitis Model.

Our in vitro studies of Pic protease suggested both pro- and antiinflammatory contributions to Shigella pathogenesis. To discern which of these effects prevailed in the setting of acute Shigella-induced inflammation, we used the widely used guinea pig keratoconjunctivitis model (26), in which the evolution of the inflammatory response to Shigella infection can be observed over time. Compared with wild-type S. flexneri 2a strain 2457T, the pic protease mutant induced a greater inflammatory response over the first 2 d of the infection (Fig. S8); after this, time differences in the inflammation response were less apparent. We ruled out the possibility of incidental mutations in 2457Tpic by reconstructing the native pic gene using allelic exchange. We simultaneously ruled out any effect of SetAB enterotoxin encoded in the complementary strand of the pic gene by creating stop codons in the setAB gene without affecting the Pic amino acid sequence (see SI Materials and Methods). S. flexneri 2457T harboring the reconstructed pic/setAB gene induced inflammation over the first 2 d that was similar to the wild-type and significantly less than that induced by the pic mutant (Fig. S8) (P < 0.05).

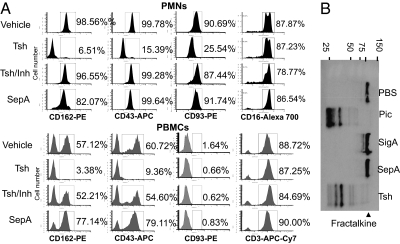

Other Class 2 SPATEs Induce Effects Similar to Pic.

To determine if other members of the class 2 SPATEs cleave targets similar to those recognized by Pic, we treated human leukocytes with the purified Tsh protein of avian pathogenic E. coli, which differs in only two residues from Hbp, found in human invasive E. coli. Tsh degraded all leukocyte O-glycans tested, including PSGL-1, CD43, CD93, and fractalkine (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Tsh degrades the extracellular domain of O-glycosylated mucin-like proteins on human leukocytes. (A) 1 × 106 PMNs and PBMCs were isolated from human blood and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. with 1 μM of purified Tsh or Tsh previously inactivated with AEBSF (serine protease inhibitor). SepA was used as a protein control for digestion. Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry using monoclonal antibodies against the extracellular domain of PSGL-1, CD43, CD93, CD3, and CD16. PMNs and PBMCs were gated as in Fig 2B. Flow cytometry results are representative of at least three independent experiments. (B) Human recombinant fractalkine was treated with 2 μM of purified Pic, SepA, Tsh, or SigA for 1 h at 37 °C and analyzed by Western blot using a monoclonal antibody against human fractalkine.

Discussion

Pic efficiently cleaves leukocyte surface glycoproteins involved in diverse human immune functions. In this article, we show that Pic substrates include a remarkable array of O-linked glycans modified with SLeX.

One of these targets, CD43, is among the most abundant mucin-like leukocyte surface glycoproteins, and is expressed on nearly all lineages of hematopoietic cells, including cells of the bone marrow, the thymus, and peripheral lymphoid tissues (27). In its native form, CD43 prevents leukocytes from adhering to neighboring cells, thereby permitting migration in response to chemokine attraction. Upon processing, the protein plays an opposite role: facilitating binding of the leukocyte to neighboring cells (28, 29). Szabady et al. reported recently that the StcE protease of enterohemorrhagic E. coli inhibits PMN chemoattraction and function by cleavage of CD43 (30). Our data suggest that leukocyte CD43 may also be affected by the pathogens S. flexneri, EAEC, UPEC, avian pathogenic E. coli, and human invasive E. coli, thereby underscoring the pathogenic importance of this phenomenon among diverse systems (Fig. S9).

Pic's other targets could be at least as important as CD43. Pic cleaves PSGL-1, involved in leukocyte trafficking and tethering to endothelial selectins (reviewed in ref. 31); the multifunctional cell-surface glycoprotein CD44, controlling cell migration through cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions (32, 33); the CD45 receptor-like protein tyrosine phosphatase, involved in cell adhesion, migration, modulation of cytokine production and signaling (34, 35); the CD93 glycoprotein, promoting migration, phagocytosis of antibody and complement opsonized particles (36, 37); and fractalkine/CX3CL1, a membrane-bound chemokine that functions not only as a chemoattractant but also as an adhesion molecule induced on activated endothelial cells by proinflammatory cytokines (38, 39). Cleavage of these diverse substrates could result in dramatic paralysis of the leukocyte-mediated response at a local level.

The mechanism of Pic's substrate specificity is noteworthy. SLeX is a tetrasaccharide carbohydrate that is usually attached to O-glycans, such as PSGL-1, but which is also found on other glycans, including mucin, CD43, and CD44. This molecule has a vital role in cell-to-cell recognition processes and is a determinant of both E- and P-selectins. Binding to this particular glycan group provides important functional specificity for Pic, which has apparently exploited the host's use of SLeX as a common inflammatory response signature. The recognition of mucin by Pic via its glycan substitutions has been previously suggested (40). As in that prior report, we found that protease-deficient Pic retains some functions, presumably via noncatalytic substrate binding.

We were surprised that Pic induced PMN activation and programmed T-cell death. The effects on PMN activation and T-cell apoptosis could result from cross-linking of PSGL-1, CD43, CD44, CD45, or CD99 on leukocytes; such cross-linking by specific antibodies or their natural ligands is known to result in activation of the oxidative bust and apoptosis (22–25, 41). Beside the O-glycoproteins tested in this study, CD34, CD68, CD99, CD164, and the recently discovered Tim (T-cell Ig-mucin domain) cluster, a family of proteins harboring mucin-like domains, represent potential targets for Pic and Pic-related proteases.

Cleavage of the mucin-like glycoproteins involved in leukocyte trafficking prevent chemoattraction and migration of leukocytes, and may also inhibit their antibacterial functions once arrived at the nidus of infection. In another scenario, premature nonspecific activation of PMNs may enhance inflammation, including aggravated tissue damage and increased recruitment of leukocytes to the area. Moreover, apoptosis of T cells by Pic would prolong an aberrant and misdirected inflammatory response, given the central role of T-cell–generated IFN-γ in sterilization of Shigella infection (42). In the Guinea pig keratoconjuctivitis model, Pic produced an antiinflammatory effect. Should this effect prevail in the setting of human shigellosis, it could retard induction of innate and adaptive responses that would be expected to control bacterial multiplication. Further understanding of the role of Pic in shigellosis will require more detailed investigations in multiple models, perhaps including volunteer studies.

Pic is expressed almost exclusively by S. flexneri 2a, which is consistently the dominant Shigella serotype worldwide; Pic may account for this epidemiologic dominance. Interestingly, Pic and Tsh are also associated with E. coli strains that cause extraintestinal infections (43), supporting our hypothesis that their roles involve targeting of general immune functions operating at diverse niches (Fig. S9). Further research in our laboratories will explore these potential roles and their clinical implications. We recognize, in addition, that the broad functionality of Pic and related proteases presents therapeutic opportunities against a large number of inflammatory disorders.

Materials and Methods

Detailed experimental procedures are given in SI Materials and Methods. Purification of SPATE proteins was previously described (5). Transmigration, chemotaxis and oxidative burst assays were performed according to described protocols (44–46). Apoptosis induced by Pic on activated T lymphocytes was determined according to the protocol recently published (41). The keratoconjunctivitis model is described in SI Materials and Methods and ref. 26.

Ethics Statement.

Blood from healthy donators were obtained under informed consent under protocol HP-00042957, approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland School of Medicine Human Subjects committee. Animal experiments were conducted according to the protocol 0210016, approved by the University of Maryland at Baltimore-International Animal Care and Use Committee.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Regina Harley and Jill Harper for technical assistance. This work was supported by United States Public Health Service Grants AI-33096 and AI-43615 (to J.P.N.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1101006108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:123–140. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Ryan M, Prado V, Pickering LK. A millennium update on pediatric diarrheal illness in the developing world. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2005;16:125–136. doi: 10.1053/j.spid.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson IR, Navarro-Garcia F, Nataro JP. The great escape: Structure and function of the autotransporter proteins. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:370–378. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01318-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson IR, Nataro JP. Virulence functions of autotransporter proteins. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1231–1243. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1231-1243.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dutta PR, Cappello R, Navarro-García F, Nataro JP. Functional comparison of serine protease autotransporters of enterobacteriaceae. Infect Immun. 2002;70:7105–7113. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.7105-7113.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Hasani K, Navarro-Garcia F, Huerta J, Sakellaris H, Adler B. The immunogenic SigA enterotoxin of Shigella flexneri 2a binds to HEp-2 cells and induces fodrin redistribution in intoxicated epithelial cells. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e8223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canizalez-Roman A, Navarro-García F. Fodrin CaM-binding domain cleavage by Pet from enteroaggregative Escherichia coli leads to actin cytoskeletal disruption. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:947–958. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navarro-García F, Canizalez-Roman A, Luna J, Sears C, Nataro JP. Plasmid-encoded toxin of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli is internalized by epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1053–1060. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.1053-1060.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otto BR, van Dooren SJ, Nuijens JH, Luirink J, Oudega B. Characterization of a hemoglobin protease secreted by the pathogenic Escherichia coli strain EB1. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1091–1103. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Provence DL, Curtiss R., 3rd Isolation and characterization of a gene involved in hemagglutination by an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1369–1380. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1369-1380.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson IR, Czeczulin J, Eslava C, Noriega F, Nataro JP. Characterization of pic, a secreted protease of Shigella flexneri and enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5587–5596. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5587-5596.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parham NJ, et al. PicU, a second serine protease autotransporter of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;230:73–83. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00862-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajakumar K, Sasakawa C, Adler B. Use of a novel approach, termed island probing, identifies the Shigella flexneri she pathogenicity island which encodes a homolog of the immunoglobulin A protease-like family of proteins. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4606–4614. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4606-4614.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leyton DL, Sloan J, Hill RE, Doughty S, Hartland EL. Transfer region of pO113 from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli: Similarity with R64 and identification of a novel plasmid-encoded autotransporter, EpeA. Infect Immun. 2003;71:6307–6319. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6307-6319.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrington SM, et al. The Pic protease of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli promotes intestinal colonization and growth in the presence of mucin. Infect Immun. 2009;77:2465–2473. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01494-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Navarro-Garcia F, et al. Pic, an autotransporter protein secreted by different pathogens in the Enterobacteriaceae family, is a potent mucus secretagogue. Infect Immun. 2010;78:4101–4109. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00523-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Restieri C, Garriss G, Locas MC, Dozois CM. Autotransporter-encoding sequences are phylogenetically distributed among Escherichia coli clinical isolates and reference strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1553–1562. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01542-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parham NJ, et al. Distribution of the serine protease autotransporters of the Enterobacteriaceae among extraintestinal clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4076–4082. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.4076-4082.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohtsubo K, Marth JD. Glycosylation in cellular mechanisms of health and disease. Cell. 2006;126:855–867. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marth JD, Grewal PK. Mammalian glycosylation in immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:874–887. doi: 10.1038/nri2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lund-Johansen F, et al. Activation of human monocytes and granulocytes by monoclonal antibodies to glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored antigens. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2782–2791. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Artus C, et al. CD44 ligation induces caspase-independent cell death via a novel calpain/AIF pathway in human erythroleukemia cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:5741–5751. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bazil V, Brandt J, Tsukamoto A, Hoffman R. Apoptosis of human hematopoietic progenitor cells induced by crosslinking of surface CD43, the major sialoglycoprotein of leukocytes. Blood. 1995;86:502–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernard G, et al. Apoptosis of immature thymocytes mediated by E2/CD99. J Immunol. 1997;158:2543–2550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klaus SJ, Sidorenko SP, Clark EA. CD45 ligation induces programmed cell death in T and B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1996;156:2743–2753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sereny B. Experimental keratoconjunctivitis shigellosa. Acta Microbiol Acad Sci Hung. 1957;4:367–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenstein Y, Santana A, Pedraza-Alva G. CD43, a molecule with multiple functions. Immunol Res. 1999;20:89–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02786465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manjunath N, Johnson RS, Staunton DE, Pasqualini R, Ardman B. Targeted disruption of CD43 gene enhances T lymphocyte adhesion. J Immunol. 1993;151:1528–1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seveau S, Keller H, Maxfield FR, Piller F, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L. Neutrophil polarity and locomotion are associated with surface redistribution of leukosialin (CD43), an antiadhesive membrane molecule. Blood. 2000;95:2462–2470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szabady RL, Lokuta MA, Walters KB, Huttenlocher A, Welch RA. Modulation of neutrophil function by a secreted mucinase of Escherichia coli O157:H7. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000320. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carlow DA, et al. PSGL-1 function in immunity and steady state homeostasis. Immunol Rev. 2009;230:75–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lesley J, Hyman R, Kincade PW. CD44 and its interaction with extracellular matrix. Adv Immunol. 1993;54:271–335. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60537-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jalkanen S, Jalkanen M. Lymphocyte CD44 binds the COOH-terminal heparin-binding domain of fibronectin. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:817–825. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.3.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harvath L, Balke JA, Christiansen NP, Russell AA, Skubitz KM. Selected antibodies to leukocyte common antigen (CD45) inhibit human neutrophil chemotaxis. J Immunol. 1991;146:949–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lai JC, Wlodarska M, Liu DJ, Abraham N, Johnson P. CD45 regulates migration, proliferation, and progression of double negative 1 thymocytes. J Immunol. 2010;185:2059–2070. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steinberger P, et al. Identification of human CD93 as the phagocytic C1q receptor (C1qRp) by expression cloning. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bohlson SS, Zhang M, Ortiz CE, Tenner AJ. CD93 interacts with the PDZ domain-containing adaptor protein GIPC: Implications in the modulation of phagocytosis. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:80–89. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0504305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bazan JF, et al. A new class of membrane-bound chemokine with a CX3C motif. Nature. 1997;385:640–644. doi: 10.1038/385640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fong AM, et al. Fractalkine and CX3CR1 mediate a novel mechanism of leukocyte capture, firm adhesion, and activation under physiologic flow. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1413–1419. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gutiérrez-Jiménez J, Arciniega I, Navarro-García F. The serine protease motif of Pic mediates a dose-dependent mucolytic activity after binding to sugar constituents of the mucin substrate. Microb Pathog. 2008;45:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen SC, et al. Cross-linking of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 induces death of activated T cells. Blood. 2004;104:3233–3242. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le-Barillec K, et al. Roles for T and NK cells in the innate immune response to Shigella flexneri. J Immunol. 2005;175:1735–1740. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heimer SR, Rasko DA, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Mobley HL. Autotransporter genes pic and tsh are associated with Escherichia coli strains that cause acute pyelonephritis and are expressed during urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 2004;72:593–597. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.593-597.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamamoto H, Sedgwick JB, Vrtis RF, Busse WW. The effect of transendothelial migration on eosinophil function. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;23:379–388. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.3.3707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lokuta MA, Huttenlocher A. TNF-alpha promotes a stop signal that inhibits neutrophil polarization and migration via a p38 MAPK pathway. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:210–219. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0205067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith JA, Weidemann MJ. Further characterization of the neutrophil oxidative burst by flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1993;162:261–268. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90391-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.