Abstract

Three randomized experiments found that subtle linguistic cues have the power to increase voting and related behavior. The phrasing of survey items was varied to frame voting either as the enactment of a personal identity (e.g., “being a voter”) or as simply a behavior (e.g., “voting”). As predicted, the personal-identity phrasing significantly increased interest in registering to vote (experiment 1) and, in two statewide elections in the United States, voter turnout as assessed by official state records (experiments 2 and 3). These results provide evidence that people are continually managing their self-concepts, seeking to assume or affirm valued personal identities. The results further demonstrate how this process can be channeled to motivate important socially relevant behavior.

Keywords: psychology, intervention, field experiment, language and thought

Why do people vote? Mass voting is essential to a well-functioning democracy, yet theorists have often pointed out that, from the standpoint of individual self-interest, voting is irrational (1–3). Just the probability of being killed in a car accident on the way to the polls far outweighs the likelihood that the average American's vote will influence the outcome of most elections.

Previous research has shown that people have a strong desire to see themselves as competent, morally appropriate, and worthy of social approval (4–11). They also see voting as appropriate and socially desirable (12, 13). Thus, being the kind of person who votes may be seen as a way to build and maintain a positive image of the self—to claim a desired and socially valued identity. Accordingly, people may be more likely to vote when voting is represented as an expression of self—as symbolic of a person's fundamental character—rather than as simply a behavior.

We tested this hypothesis in three randomized experiments. In the first, we investigated the reported interest in registering to vote of people who were eligible but had not yet registered to vote; in the second and third, we examined voter turnout as assessed by official state records. In each experiment, participants completed one of two versions of a brief survey. In one version, a short series of questions referred to voting using a self-relevant noun (e.g., “How important is it to you to be a voter in the upcoming election?”); in the other, questions that were otherwise identical referred to voting using a verb (e.g., “How important is it to you to vote in the upcoming election?”). This manipulation draws on past research investigating the effects of linguistic cues on social- and self-perception (14, 15). Noun wording leads people to see attributes as more representative of a person's essential qualities. In one study, children thought that a child described as “a carrot eater” liked carrots more than a child who “eats carrots whenever she can” (14). In another study, adults rated their own preferences as stronger and more stable when induced to describe them with nouns (e.g., “I am a Shakespeare-reader”) than with the related verbs (e.g., “I read Shakespeare a lot”) (15).

In this past research, people were labeled in the here and now, but in the present research, people were offered the opportunity to claim an identity in the future. That is, using noun wording to refer to a prospective behavior offers the possibility of claiming or reclaiming a personal attribute by engaging in that behavior. So we hypothesized that using a predicate noun (e.g., “to be a voter”) as opposed to a verb (e.g., “to vote”) to refer to participation in an upcoming election would create a greater interest in and likelihood of performing that behavior—registering to vote and voting. If this hypothesis were confirmed, it would be evidence for the more general theoretical idea that simply framing a future behavior as a way to claim a desired identity can motivate that behavior.

Experiment 1

Participants in experiment 1 were people who were eligible to vote in the 2008 presidential election in California but were not registered to vote at the time of participation. After completing the noun- or the verb-based survey, they were informed that, to vote in the upcoming election, they would need to register and were asked to indicate their level of interest in doing so.

As predicted, participants in the noun condition expressed significantly greater interest in registering to vote than participants in the verb condition. Because the distribution of reported interest in registering to vote was negatively skewed (Z = −2.78, P = 0.005), the variable was reflected and then square-root transformed, which reduced skew to nonsignificance (Z = −1.76, P = 0.078). A t test on the transformed variable yielded a significant condition difference [t(32) = 2.10, P = 0.044]. Analysis of the untransformed variable also yields a significant result [(Mnoun = 4.44; Mverb = 3.39; 1 = “not at all interested,” 5 = “extremely interested”), t(32) = 2.23, P = 0.033].

A significant Levene's test indicated that there was less variance in the noun condition than in the verb condition [F(1,32) = 6.02, P = 0.020]. This appeared to be the case because of a ceiling effect in the noun condition, where 62.5% of participants were at the highest point on the scale (compared with 38.9% in the verb condition). Adjusting for this, the significance level of the condition effect strengthened slightly [t(29.40) = 2.15, P = 0.040]. In addition, a separate χ2 analysis, which does not rely on the assumption of the equality of variance, found that more participants indicated that they were “very” or “extremely” interested in registering to vote (as opposed to “not at all,” “a little,” or “somewhat” interested in registering to vote) in the noun condition (87.5%) than in the verb condition (55.6%) [χ2(1, n = 34) = 4.16, P = 0.041].

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 tested the effect of the noun-vs.-verb manipulation on voter turnout. Participants were registered to vote in California and had not already voted (e.g., by mail) in the 2008 presidential election. They were recruited for an “election survey” and completed the noun- or verb-based manipulation survey the day before or the morning of the election. After completing the manipulation survey, participants were thanked; this marked the end of their active participation in the study.

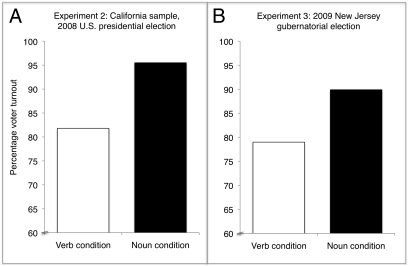

After the election, we used official records from the State of California (13, 16, 17, 18) to determine whether each participant had or had not voted in the election. We also used US Census data (19) to estimate the premanipulation probability that each participant would vote on the basis of their age, gender, and level of education. This variable, which was a significant predictor of turnout [Δχ2(1, n = 88) = 8.23, P = 0.004] and did not differ between conditions [t(86) = 0.59, not significant (ns)], served as a covariate. Logistic regression tested the effect of the noun-vs.-verb manipulation on voting. As predicted, participants in the noun condition voted at a significantly higher rate (95.5%) than participants in the verb condition (81.8%) [Δχ2(1, n = 88) = 5.55, P = 0.018] (Fig. 1A).*

Fig. 1.

Percentage voter turnout in the noun and verb conditions in experiments 2 and 3. (A) Experiment 2: California registered voters, 2008 US presidential election. (B) Experiment 3: New Jersey registered voters, 2009 New Jersey gubernatorial election.

In addition to the condition difference, the overall turnout rate in our sample merits consideration. The turnout rate in the verb condition of 81.8%, although not meaningfully higher than the statewide turnout rate of 79.4% among registered voters in this election, was higher than would be expected given the demographic makeup of the sample. Using US Census data on turnout rates in this election by age, gender, and level of education (19), the expected premanipulation turnout rate of participants in our sample was 63.9% (95% confidence interval: 61.9–66.0%).

We suggest two possible reasons why the turnout rate, even in the verb condition, was higher than this expected baseline rate. First, people who choose to participate in a survey related to an upcoming election—or even those who have the time and inclination to participate in any survey shortly before an election—may be more likely to vote than the general population. Second, some research suggests that merely responding to a pre-election survey can increase voter turnout (16, 17, 20, 21; but see ref. 18). These findings highlight the rigorous nature of the control condition in the present research, which used questions that were nearly identical to those in the treatment condition. In any case, the critical finding from experiment 2 is that a subtle change in the phrasing of survey items, which cast voting as a reflection of the kind of person one is rather than as merely a behavior, significantly increased voter turnout.

Experiment 3

Is the influence of noun-vs.-verb wording specific to the type of people who took part in experiments 1 and 2, or would it occur more broadly? The participants in experiments 1 and 2 were relatively young (Mage = 22.8 y, range = 18–70). A manipulation like the present one, which relies on the malleability of the self-concept, might be more effective at influencing young adults, whose self-concepts may be less well defined than those of older people (22). Experiment 3 tested the effect of the noun-vs.-verb manipulation in a larger and more diverse sample (Mage = 54.4 y, range = 21–83). Participants were registered to vote in New Jersey and had not already voted (e.g., by mail) in the 2009 New Jersey gubernatorial election. They were recruited from a randomly sampled and nationally representative panel administered by a professional survey research firm. The participant sample did not differ from the representative statewide sample with respect to most demographic characteristics, and those differences that did exist were small (see Methods for details). Unlike experiment 2, participants were not aware, at the time they agreed to participate, that the experiment was related to the election. They completed the noun- or verb-based manipulation survey the day before or the morning of the election.

As in experiment 2, after the election we used official state records to determine whether or not each participant had voted. Census data needed to estimate participants’ premanipulation probability of voting were not available for this off-year election. However, even without this covariate, the noun-vs.-verb manipulation again had a significant effect on voter turnout [Δχ2(1, n = 214) = 4.91, P = 0.027]. Participants in the noun condition voted at a higher rate (89.9%) than participants in the verb condition (79.0%; Fig. 1B). This effect was not significantly moderated by age, gender, ethnicity (white vs. non-white), level of education, household income, political orientation, or interest in politics and public affairs (all Ps > 0.22).†

As was the case in experiment 2, the turnout rate in both conditions in experiment 3 was higher than the expected baseline—in the New Jersey election, the statewide turnout rate among registered voters was 47%. As we noted above, this may be because people who have the time and inclination to complete any survey shortly before an election might be more likely to vote than the general population and/or because merely completing a pre-election survey can increase turnout (16, 17, 20, 21). Indeed, future research could explore the relative importance of these explanations by including a baseline condition in which participants do not complete any survey. Again, however, the critical finding is that a small change in wording that framed voting as an expression of self rather than as simply a behavior increased voter turnout—in this experiment by 10.9 percentage points.

Discussion

This research shows that people's desire to shape their own identities can be harnessed to motivate behavior. That is, using noun-based wording to frame socially valued future behavior allows individuals, by performing the behavior, to assume the identity of a worthy person.

Although the wording manipulation in these studies was subtle and rigorously controlled, the effects observed in experiments 2 and 3 are among the largest experimental effects ever observed on objectively measured voter turnout. In discussing the magnitude of this effect, we focus on experiment 3, which used a larger and more demographically diverse sample, and not on experiment 2 where the effect was, if anything, larger but the sample was smaller and less diverse. Experiment 3 found an increase in turnout in the noun condition of 10.9 percentage points, a 13.7% boost in turnout over the verb condition. It is fascinating to consider whether this effect would remain as strong if delivered at the population level. Although there might be important factors that could decrease or increase the strength of the effect in different populations, a large-scale intervention that produced an increase in voter turnout even close to the size observed here would have major effects on democratic participation, and possibly on election outcomes. For example, if the losing side in every congressional and gubernatorial race in 2010 had increased turnout among its supporters by just 5%, 23 House races, 3 Senate races, and 8 governor's races would have turned out differently.

Because voting is a private action, people who vote may receive little or no recognition from others for doing so. This may help to explain why many people do not vote. The present research suggests a way to ameliorate this problem. By highlighting the implications of voting for one's self-concept, the use of noun wording may offer an alternative incentive to vote: positive self-regard. Indeed, many behaviors that policy-makers seek to encourage are similarly private, including environmental behaviors such as energy conservation and recycling. Such behaviors may be ideal candidates for research extending the present results.

Although participants responded strongly to this subtle language manipulation, they did not do so in a rote or mindless fashion. The effect we observed depends on the fact that voting is something most people feel that they should do. The noun wording, we contend, simply ascribed symbolic significance to this behavior, suggesting it had implications for the kind of person one is. Therefore, we do not believe that a manipulation of this sort would induce people to engage in behavior in which they feel they should not engage. In fact, we would expect the opposite effect for behavior people see as undesirable (e.g., “cheating” vs. “being a cheater”; “quitting” vs. “being a quitter”).

More broadly, these experiments provide evidence that the self-concept is a continual work-in-progress. In part because of this, the self can play a key role in shaping socially relevant behavior. This desire to see oneself as good, competent, and worthy of approval can be channeled, even through subtle means, to motivate behavior with important social and political consequences.

Methods

Experiment 1.

Participants and design.

Participants were recruited via advertisements on a social networking website and invited to complete a brief survey about the 2008 presidential election in exchange for an entry in a drawing to win $100. A screening questionnaire identified participants who met a priori specified eligibility criteria: participants who (i) were eligible to vote in this election, (ii) had not already registered to vote, and (iii) were native English speakers. Thirty-four participants met these criteria (21 women and 13 men; Mage = 19.9 y; SD = 1.79). Eligible participants were randomly assigned to either the noun condition or the verb condition.

Manipulation.

The manipulation was embedded in a 10-item survey. The content of each question was identical in the two conditions; the only difference was the specific wording used to refer to the act of voting—verb-based wording in one condition and noun-based wording in the other [e.g., “How important is it to you to (vote/be a voter) in the upcoming election?”, “How clear are your thoughts and feelings about (voting/being a voter) in the upcoming election?”; see SI Methods for the full list of items]. Participants responded to each question on a five-point scale with verbal labels appropriate to the content of the question.

Participants’ responses to a composite of all 10 manipulation items did not differ between conditions [t(32) = 0.92, ns] nor did their responses to 9 of the 10 individual items (all Ps > 0.20; see SI Methods for details).

Finally, participants were informed that, to vote in the upcoming election, they would need to register to vote. The key outcome was participants’ self-reported interest in registering to vote. They were asked: “Right now, how interested are you in registering to vote in the upcoming election?” (1 = “not at all interested,” 5 = “extremely interested”). There were no outliers on the dependent variable; all scores fell within 1.96 SDs of the mean.

Experiment 2.

Participants and design.

Participants were recruited on the afternoon of November 3 or early on the morning of November 4, 2008 (i.e., Election Day) through advertisements on the same social networking website used in experiment 1 and through an advertisement distributed to members of a university-administered online participant pool. Advertisements described the experiment as an “election survey.” A screening questionnaire identified participants who met eligibility criteria similar to those used in experiment 1: participants who (i) were registered to vote in California, (ii) had not already voted (e.g., by mail) in the election, and (iii) were native English speakers. A total of 133 participants met these criteria and were randomly assigned to either the noun or the verb condition. Demographic data provided by participants (name, county of residence, and date of birth) were compared with California voter turnout records to determine whether each participant had voted or not (see Procedure for additional details). State records had matches for 92 of these participants. Additional analyses tested for outliers (23) on the basis of participants’ condition assignment and their premanipulation likelihood of voting (Premanipulation likelihood of voting). Four participants were excluded because their residual scores based on these data were outliers (i.e., standardized residuals >2.58, the level associated with a two-tailed α of 0.01). The remaining 88 participants (56 women and 32 men; Mage = 23.7 y; SD = 5.9) make up the final sample.

Procedure.

The procedure was identical to that of experiment 1 except that (i) the manipulation questions referred to “tomorrow's election” instead of “the upcoming election” and (ii) instead of being asked about their interest in registering to vote, participants were asked to provide the demographic data needed to find their listings in state voting records. After the election, a copy of California's voter history file was obtained from the office of the California Secretary of State. The data included the first name, last name, county of residence, and voting history of all of California's registered voters. A research assistant, who was blind to condition, searched for each of the 133 eligible participants in the state data. A listing in the state file was considered to match a study participant if it had the same first name, last name, date of birth, and county of residence provided by the participant. Cases in which a participant's last name, date of birth, and county of residence matched but the first name a participant provided was similar but not identical to the first name listed in the state file (e.g., “Eddie” or “E.” instead of “Edward”) were considered to be matches. The match rate did not differ between conditions [χ2 (1, n = 92) = 0.59, ns]. Participants’ responses to a composite of all 10 manipulation items did not differ between conditions [t(86) = 0.64, ns] nor did responses to any individual item (all Ps > 0.10).

Premanipulation likelihood of voting.

After the election, we obtained data from the US Census on self-reported voter turnout among registered voters in the 2008 presidential election by age, gender, and level of education. We used these data to determine the baseline (or premanipulation) expected likelihood that each participant would vote. As noted, expected turnout rates did not differ between conditions [t(86) = 0.59, ns], and this variable was used as a covariate in the main analysis. It was a significant predictor of turnout [Δχ2(1, n = 88) = 8.23, P = 0.004].

Experiment 3.

Participants and design.

Participants were members of a randomly sampled and nationally representative panel administered by the professional survey research firm Knowledge Networks. Only panel members who lived in New Jersey and were registered to vote in that state at the time of the study were invited to participate. All participants took part in the study on the afternoon of November 2 or early the morning of November 3, 2009 (i.e., Election Day). In contrast to experiments 1 and 2, the invitation to panel members to participate in experiment 3 included no mention of the upcoming election. This ruled out any bias that might arise from limiting the sample to people who were unusually interested in the election. A total of 350 panel members completed the study. A screening questionnaire identified participants who met the same criteria used in experiment 2. A total of 293 participants met those criteria. Of these, 214 (129 women, 85 men) were matched in official New Jersey voter turnout records (see Procedure for additional details). Whereas the people sampled in experiments 1 and 2 were on average relatively young (Mage = 22.6 y, SD = 5.4, range = 18–70), the people sampled in experiment 3 were on average middle-aged (Mage = 54.4 y, SD = 13.9, range = 21–83). The demographic makeup of the sample was similar to that of the rest of Knowledge Networks’ randomly sampled and representative statewide panel. That is, the sample did not differ from the panel with respect to most demographic variables (i.e., gender, marital status, employment status, household size, housing type, home ownership status, or internet access; all Ps > 0.17). The sample did, however, differ somewhat in terms of its racial/ethnic breakdown (sample: 86.4% white, 7.9% black, 1.4% non-Hispanic other, 3.3% Hispanic, and 0.9% multiracial; rest of the statewide panel: 77.1% white, 7.4% black, 6.4% non-Hispanic other, 7.1% Hispanic, and 2.0% multiracial) [χ2(4, n = 809) = 14.29, P = 0.006]. The panel was also marginally more educated [Msample = 11.37, Mpanel = 11.14, where 11 = an associate degree and 12 = a bachelor's degree; t(807) = 1.84, P = 0.066], had a marginally higher average income [Msample = 14.36, Mpanel = 13.85, where 13 = $60,000–$74,999, 14 = $75,000–$84,999, and 15 = $85,000–$99,999; t(807) = 1.74, P = 0.082], and was marginally older [Msample = 54.42 y, Mpanel = 52.27 y; t(807) = 1.86, P = 0.063] than the rest of the panel. The effect of condition, however, did not interact with any of these demographic variables.

Because US Census Bureau data needed to estimate the premanipulation probability that each participant would vote were not available in this off-year election, residual scores for individual participants were based solely on their condition assignments. As a consequence, an outlier analysis similar to the one conducted in experiment 2 identified every nonvoting participant in the noun condition as an outlier. Excluding these participants would inappropriately inflate the size of the observed effect; thus all participants were retained in the analysis.

Demographic measures.

To test for moderation by demographic variables, we obtained measures of participants’ age, ethnicity, gender, level of education, household income, political orientation, and interest in politics and public affairs. Political orientation was measured with a composite of participants’ self-reported party preference and liberal–conservative ideological orientation, both on seven-point scales (1 = strong Republican/extremely conservative; 7 = strong Democrat/extremely liberal). The two items were correlated (r = 0.54, P < 0.0005). Interest in politics and public affairs was measured on a four-point scale (1 = “not at all interested”; 4 = “very interested”).

Procedure.

The procedure was the same as the one in experiment 2 with three exceptions. First, the manipulation items referred to “tomorrow's election” only until 11:59 PM on November 2; from midnight on November 3 until the close of recruitment, the items referred to “today's election.” Second, minor changes were made to the wording of several manipulation items (SI Methods). Third, participants were not asked to provide demographic data at the time they completed the manipulation survey because Knowledge Networks already had the information needed to match panel members to state voting records. After the election, a copy of New Jersey's voter history file was obtained from the office of the New Jersey Secretary of State. As in California, the data included the first name, last name, county of residence, and voting history of all of New Jersey's registered voters. Because Knowledge Networks is obligated to protect the identities of its panel members, we provided the state file to them and a member of their staff, who was blind to both the study's hypotheses and to the participants’ condition assignment, searched for each of the 293 eligible participants in the state file. As in experiment 2, a listing in the state file was considered to match a study participant if it had the same first name, last name, date of birth, and county of residence provided by the participant. Also as in experiment 2, cases in which a participant's last name, date of birth, and county of residence matched but the first name that the participant provided was similar but not identical to the first name listed in the state file were considered to be matches. The match rate again did not differ between conditions [χ2(1, n = 293) = 0.19, ns].

Responses to a composite of all 10 manipulation items did not differ between conditions [t(212) = 0.76, ns] nor did responses to 8 of the 10 individual items (all Ps > 0.10; see SI Methods for details).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Boroditsky, H. Clark, A. Gerber, D. Green, J. Krosnick, H. Markus, B. Monin, L. Ross, D. Yeager, and two anonymous reviewers for input and L. Handal-Kalifa, D. Kermer, D. Miller, J. Ternovski, and K. Wang for assistance. Funding for experiment 3 was provided by Grant 0818839 (to C.J.B., G.M.W., and T.R.) awarded by Time-Sharing Experiments in the Social Sciences, National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1103343108/-/DCSupplemental.

*The design and sample size of experiment 2 do not allow reliable tests of moderation by demographic variables. The dependent variable was dichotomous, and one of the possible outcomes (not voting) was relatively rare. As a result, breaking the sample down by more than one dimension to test for moderation creates the possibility of empty cells. Moderation tests were therefore conducted with the larger sample in experiment 3.

†To maximize statistical power for these analyses, we pooled data from experiments 2 and 3 when the same demographic variables were assessed in both studies (i.e., age, gender, and ethnicity). Results of these tests did not differ when we used only the sample in experiment 3.

References

- 1.Downs A. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper & Row; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers T, Fox CR, Gerber AS. In: The Behavioral Foundations of Policy. Shafir E, editor. New York: Russell Sage; [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tullock G. Towards a Mathematics of Politics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunning D. In: Motivated Social Perception: The Ontario Symposium. Fein S, Spencer S, editors. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen GL, Garcia J, Apfel N, Master A. Reducing the racial achievement gap: A social-psychological intervention. Science. 2006;313:1307–1310. doi: 10.1126/science.1128317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins ET. Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychol Rev. 1987;94:319–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markus H, Nurius P. Possible selves. Am Psychol. 1986;41:954–969. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monin B, Miller DT. Moral credentials and the expression of prejudice. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81:33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oyserman D. Identity-based motivation: Implications for action-readiness, procedural-readiness and consumer behavior. J Consum Psychol. 2009;19:250–260. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman DK, Cohen GL. The psychology of self-defense: Self-affirmation theory. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. San Diego: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 183–242. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steele CM. The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. New York: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 261–302. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blais A. To Vote or Not to Vote: The Merits and Limits of Rational Choice Theory. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerber AS, Green DP, Larimer CW. Social pressure and voter turnout: Evidence from a large-scale field experiment. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2008;102:33–48. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelman SA, Heyman GD. Carrot-eaters and creature-believers: The effects of lexicalization on children's inferences about social categories. Psychol Sci. 1999;10:489–493. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walton GM, Banaji MR. Being what you say: The effect of essentialist linguistic labels on preferences. Soc Cogn. 2004;22:193–213. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenwald AG, Carnot CG, Beach R, Young B. Increasing voting behavior by asking people if they expect to vote. J Appl Psychol. 1987;2:315–318. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nickerson DW, Rogers T. Do you have a voting plan?: Implementation intentions, voter turnout, and organic plan making. Psychol Sci. 2010;21:194–199. doi: 10.1177/0956797609359326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith JK, Gerber AS, Orlich A. Self-prophecy effects and voter turnout: An experimental replication. Polit Psychol. 2003;24:593–604. [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Census Bureau Voting and registration in the election of November 2008. Current Population Survey. 2008. (available at http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/socdemo/voting/publications/p20/2008/tables.html)

- 20.Granberg D, Holmberg S. The Hawthorne effect in election studies: The impact of survey participation on voting. Br J Polit Sci. 1992;22:240–247. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yalch RF. Pre-election interview effects on voter turnout. Public Opin Q. 1976;40:331–336. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sears DO. College sophomores in the laboratory: Influences of a narrow data base on social psychology's view of human nature. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:515–530. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. Boston: Pearson; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.