Abstract

Overexpression of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) in β cells causes impaired insulin secretion and β cell dysfunction associated with diminished pancreatic duodenal homeodomain transcription factor-1 (PDX-1) expression in vitro and in vivo. To identify the molecular mechanism responsible for this effect, the mouse Pdx-1 gene promoter (2.7 kb) was analyzed in β cell and non-β cell lines. Despite no apparent sterol regulatory element-binding protein-binding sites, the Pdx-1 promoter was suppressed by SREBP-1c in β cells in a dose-dependent manner. PDX-1 activated its own promoter. The E-box (−104/−99 bp) in the proximal region, occupied by ubiquitously expressed upstream stimulatory factors (USFs), was crucial for the PDX-1-positive autoregulatory loop through direct PDX-1·USF binding. This positive feedback activation was a prerequisite for SREBP-1c suppression of the promoter in non-β cells. SREBP-1c and PDX-1 directly interact through basic helix-loop-helix and homeobox domains, respectively. This robust SREBP-1c·PDX-1 complex interferes with PDX-1·USF formation and inhibits the recruitment of PDX-1 coactivators. SREBP-1c also inhibits PDX-1 binding to the previously described PDX-1-binding site (−2721/−2646 bp) in the distal enhancer region of the Pdx-1 promoter. Endogenous up-regulation of SREBP-1c in INS-1 cells through the activation of liver X receptor and retinoid X receptor by 9-cis-retinoic acid and 22-hydroxycholesterol inhibited PDX-1 mRNA and protein expression. Conversely, SREBP-1c RNAi restored Pdx-1 mRNA and protein levels. Through these multiple mechanisms, SREBP-1c, when induced in a lipotoxic state, repressed PDX-1 expression contributing to the inhibition of insulin expression and β cell dysfunction.

Keywords: Gene Expression, Insulin, Pancreas, Promoters, Transcription, PDX-1, SREBP-1c

Introduction

The homeobox protein PDX-1 serves as the master control switch for expression of exocrine and endocrine pancreatic developmental programs. In adults, PDX-1 expression is restricted to the β and δ cells of the pancreas and is required for regulation of insulin (1, 2), glucose transporter 2 (3), islet amyloid polypeptide (4–6), and glucokinase (6) expression. In mice, β cell-selective disruption of Pdx-1 leads to the development of diabetes with increasing age (7). Mice heterozygous for Pdx-1 were found to be glucose-intolerant (7, 8) with increased islet apoptosis, decreased number of islets, and abnormal islet architecture (9). In humans, the mutation of Pdx-1 has been associated with the MODY4 locus (10, 11), linking PDX-1 to a form of diabetes known as maturity-onset diabetes of the young. Thus, impaired PDX-1 expression appears to be associated with diabetes (12–14).

Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs)2 are a family of transcriptional factors that regulate the transcription of genes involved in lipid synthesis (15). Three isoforms exist as follows: SREBP-1a, -1c, and -2. In the liver, SREBP-1c controls expression of lipogenic enzymes, whereas SREBP-2 is specific to cholesterol synthesis (16–19). Through its nutritional regulation, SREBP-1c is involved in insulin action in various tissues (20–22). In the liver, SREBP-1c overexpression leads to hepatic insulin resistance by directly repressing IRS-2, a crucial insulin-signaling molecule (21). In pancreatic β cells, SREBP-1c has been implicated in impaired insulin secretion (20, 22, 23). Increased SREBP-1c expression has been reported in the islets of ZDF rats (fa/fa) with ectopic overaccumulation of fat (24). Transgenic mice overexpressing SREBP-1c, SREBP-2, and SREBP-1a in β cells demonstrated impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and reduced islet mass because of decreases in the number and size of β cells (22, 25, 26). Inhibition of insulin secretion by SREBP-1c is mediated through ATP consumption, UCP-2 and PDX-1 suppression, and granuphilin activation. Induced SREBP-1c expression in β cells (INS-1) blunted nutrient-stimulated insulin secretion and decreased the mRNA of Pdx-1, insulin, and PDX-1 target genes (27). Conversely, in SREBP-1 knock-out mice, Pdx-1 mRNA expression increased (22). These results suggest that SREBP-1c could be involved in impaired insulin secretion and β cell dysfunction through PDX-1 suppression. However, the molecular mechanism by which SREBP-1c regulates PDX-1 expression in islet β cells remains unclear.

Various transcriptional factors involved in PDX-1 expression have been reported as follows: HNF-3β/Foxa2 (28), PDX-1 (28), HNF-1α (29), SP1 (29), Pax6 (30), and MafA (31) in the distal enhancer region (−1.9 to −2.7 kb), and ubiquitous transcriptional factors (USFs) in the proximal region at −104 bp (32, 33). A PDX-1-positive autoregulatory loop was suggested by studying adenovirus-mediated PDX-1 expression in the mouse pancreas, which activated the endogenous Pdx-1 and led to ductal proliferation and β cell neogenesis (34). In this study, we focused on the effects of SREBP-1c on PDX-1-positive feedback regulation as a potential mechanism by which SREBP-1c regulates Pdx-1 expression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construction of Reporter Plasmids

The 2.7-kb (−2721 to +50) fragment of the mouse Pdx-1 promoter gene was cloned using the primers 5′-GGTACCTCCAGTATCAGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GAGCTACAAGCCAGGCCT-3′ (antisense) with genomic DNA as the template; it was subcloned into the KpnI-XhoI sites of the pGL3 basic luciferase vector (Promega). The plasmids PDX-1 (−2.7 k) Em-Luc contain a mutation in the E-box motif (−104/−99 bp, CACGTG→CATAGC).

Transfection and Luciferase Assays

HIT (3.5 × 105 cell/well) and HepG2 cells (4.2 × 104 cell/well) were plated on 12-well plates. The expression plasmids, luciferase reporter plasmid (0.5 μg), and internal control pSV-β-gal (0.5 μg) were cotransfected using SuperFect transfection reagent (Qiagen) for HepG2 cells and JetPEI-Man (Polyplus transfection) for HIT cells. The total amount of DNA in each transfection was adjusted to 1.5 μg/well. The luciferase activity in transfectants was measured by MicroLumat Plus (EG&G Berthold) and normalized to the β-Gal activity measured using a standard kit (Promega).

Adenovirus Infection Studies

INS-1 cells were plated at a density of 4 × 106 cells/75-cm2 dish for 48 h before viral treatment. Cells were transduced with adenoviral vectors encoding the green fluorescent protein (Ad-GFP) as the control or human nuclear SREBP-1c(1–436) (Ad-SREBP-1c) at the indicated multiplicities of infection by incubation for 48 h at 37 °C (21). The virus-containing medium was then aspirated, and cells were cultured in 25 mm glucose medium for 6 h. Total RNA was isolated, and 10 μg of each sample was subjected to electrophoresis.

Gel Mobility Shift Assays

Gel shift assays were performed as described previously (35). In the experiment shown in Fig. 5A, nuclear extracts from INS-1 (10 μg) or HepG2 (4 μg) cells were incubated with [α-32P]dCTP-labeled double strand oligonucleotides corresponding to mouse Pdx-1 promoter proximal regions (−163 to −90 bp as follows: probe −163/−138, 5′-GGCACCTAAGCCTCCTTCTTAAGGCA-3′; probe −149/−130, 5′-CTTCTTAAGGCAGTCCTCCA-3′; probe −137/−113, 5′-GTCCTCCAGGCCAATGATGGCTCCA-3′; and probe −120/−90, 5′-TGGCTCCAGGGTAAACCACGTGGGGTGCC-3′).

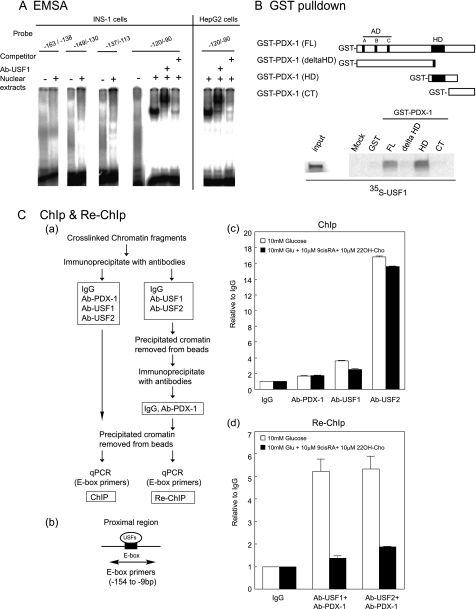

FIGURE 5.

USFs bind to the proximal E-box, and the homeobox domain of PDX-1 physically interacts with USFs. A, EMSA was performed using nuclear extracts of INS-1 and HepG2 cells and 32P-labeled probes of Pdx-1 promoter proximal regions (−163/−138-bp probe, −149/−130, −137/−113, and −120/−90). A 1000-fold excess of the unlabeled −120/−90-bp probe was used for the competition assay. USF1 antiserum was added to specify USF binding to the −120/−90-bp probe. B, in vitro translated 35S-labeled USF1 was incubated with GST-PDX-1 fusion proteins (GST-PDX-1 (full-length, FL), GST-PDX-1 (ΔHD), GST-PDX-1 (HD), and PDX-1 (CT)) immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads. Bound proteins were resolved on a 15% gel by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. C, PDX-1 association with USFs binding to the proximal E-box of the Pdx-1 promoter. Panel a, brief protocol of ChIP and Re-ChIP assays. Panel b, PCR primer for the proximal E-box. Panel c, cross-linked chromatins from INS-1 cells cultured in 10 mm glucose medium with or without 9-cis-RA (1 μm) and 22OH-Cho (1 μm). Cells were incubated with anti-PDX-1, anti-USF1, anti-USF2 antibodies, or rabbit IgG as a negative control. The immunoprecipitated DNAs were analyzed by PCR for proximal E-box primers using real time PCR. Panel d, in the Re-ChIP experiment, the DNAs immunoprecipitated by anti-USF1 or anti-USF2 antibodies were incubated with the anti-PDX-1 antibody or IgG again. The immunoprecipitates were sequentially analyzed by PCR for proximal E-box primers using real time PCR. The experiments in A–C were repeated two times with similar results.

In the experiment shown in Fig. 6C, PDX-1 and SREBP-1c proteins were prepared using a TnT-coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega). The mouse Pdx-1 promoter area I probe −2517/−2492 (5′-TCCACAGTATAATTGGTTTACAG-3′) was used.

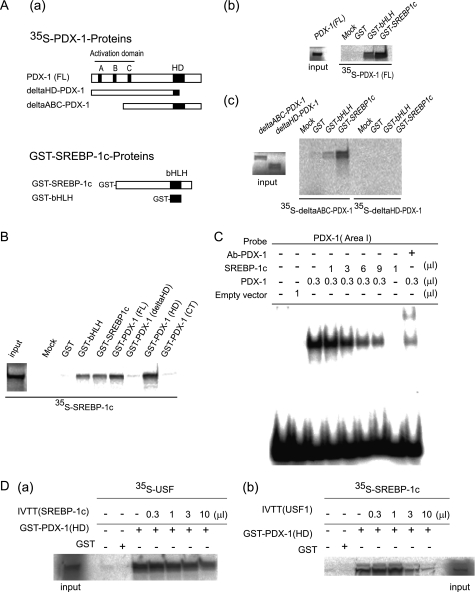

FIGURE 6.

Homeobox domain of PDX-1 physically interacts with the bHLH domain of SREBP-1c in vitro. A, panel a, schematic representation of [35S]methionine-labeled PDX-1 derivatives and GST fusion SREBP-1c derivatives. Panels b and c, in vitro translated [35S]methionine-labeled PDX-1 (full-length (FL), 1–283), ΔABC-PDX-1(76–283), or ΔHD-PDX-1(1–149)) was incubated with GST-SREBP-1c (bHLH, 286–364) or GST-SREBP-1c (nuclear form, 24–460) immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads. Bound proteins were resolved on 15% gel by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. B, in vitro translated 35S-labeled SREBP-1c(1–460) was incubated with GST-PDX-1 fusion proteins, GST-PDX-1(FL), GST-PDX-1(ΔHD), GST-PDX-1(HD), and GST-PDX-1(CT). GST-SREBP-1c (bHLH) and GST-SREBP-1c (nuclear form) were used as controls. C, EMSA was performed using indicated amounts (μl) of in vitro translated PDX-1 or SREBP-1c proteins and 32P-labeled mouse Pdx-1 promoter area I probe. The probe does not contain a SREBP-1c-binding site. PDX-1 antiserum was added to specify the PDX-1 binding to the probe. D, panels a and b, in vitro translated 35S-labeled USF1 (5 μl) or SREBP-1c (5 μl) was incubated with 1.0 μl of GST or GST-PDX-1 (HD) with in vitro translated SREBP-1c (0–10 μl) or USF1 (0–10 μl). Bound proteins were resolved on a 15% gel by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. The experiments in A–D were repeated two times with similar results.

GST Binding Assay

GST-alone, GST-SREBP-1c (nuclear form (residues 24–460)) (36), GST-SREBP-1c (bHLH(286–364)), GST-PDX-1(1–284), GST-PDX-1 (ΔHD(1–149)), GST-PDX-1 (HD(133–218), and GST-PDX-1 (CT(218–284)) were generated. Each GST fusion protein was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Promega). [35S]Methionine-labeled PDX-1(1–284), ΔHD-PDX-1(1–149), ΔABC-PDX-1(76–284), SREBP-1c(1–453), and USF1(1–310) were prepared using the TnT-coupled reticulocyte lysate system. GST precipitation assays were modified as reported previously (37, 38).

ChIP

A ChIP assay was performed as described previously (37). In the experiment shown in Fig. 5C, immunoprecipitated genomic DNA fragments were quantified by a StepOneTM real time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using Fast SYBR® Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Primer sets for the Pdx-1 proximal E-box region were 5′-GCCTCCTTCTTAAGGCA-3′ (sense) and 5′-ATCGCTTTGACAGTTCTCC-3′ (antisense). The PCR conditions were 20 s at 95 °C followed by 42 cycles of 3 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 60 °C. In the experiment shown in Fig. 9D, primer sets for mouse Pdx-1 promoter area I regions were 5′-CCACTAAGAAGGAAGGCCAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTGAGGTTCTTTCTCTGCCTCTCTG-3′ (antisense). The PCR conditions were 5 min at 94 °C followed by 31 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 50 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C. The PCR products were resolved on a 3% agarose gel.

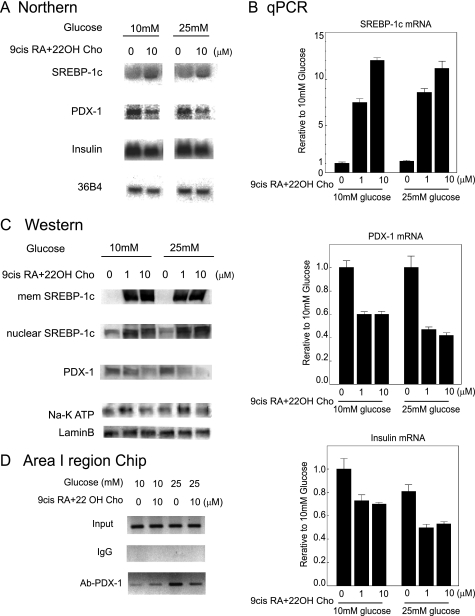

FIGURE 9.

Induction of the SREBP-1c protein by LXR·RXR suppresses PDX-1 expression. A, INS-1 cells were cultured for 18 h in 10 and 25 mm glucose with or without of 10 μm of 9-cis-RA and 10 μm 22OH-Cho. The mRNAs (10 μg) of SREBP-1, PDX-1, insulin, and 36B4 were measured. B, INS-1 cells were cultured for 18 h in 10 or 25 mm glucose medium with or without indicated amounts of 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho. The mRNAs were extracted and quantified by real time PCR (n = 3). Data are means ± S.E. Relative rate to 10 mm glucose mRNA without 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho was set to 1.0. C, INS-1 cells were cultured for 18 h in 10 and 25 mm glucose with or without indicated amount of 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho. Membrane proteins (20 μg) and nuclear proteins (40 μg) were extracted from INS-1 cells. Extracted proteins were immunoblotted with anti-SREBP-1, anti-PDX-1, anti-lamin B, and anti-Na, K ATP antibodies. D, ChIP assay in area I. Cross-linked chromatin from INS-1 cells in 10 or 25 mm glucose medium with or without 10 μm of 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho were incubated with anti-PDX-1 antibody or rabbit IgG as a negative control. The immunoprecipitated DNAs were analyzed by PCR for area I primers as indicated. The PCR products were resolved on a 3% agarose gel. The experiments in A, C, and D were repeated three times with similar results.

GAL4 Fusion Protein Reporter Gene Analysis

GAL4 fusion constructs were generated by inserting DNA fragments of rat Pdx-1 into the SalI-PstI site of the pM vector (RT3119-5, Clontech) (2). The GAL4-responsive reporter plasmid pGL-GAL4-UAS ((Gal4)8-Luc) was kindly gifted by Dr. S. Kato (Tokyo University, Tokyo, Japan) (39). The GAL4 fusion plasmids were cotransfected into HIT or HepG2 cells along with (Gal4)8-Luc and pSV-β-gal with or without the expression vectors for SREBP-1c and DN-SREBP-1. Luciferase activity was normalized to an internal control of pSV-β-gal.

Construction of siRNA Specific for SREBP-1c

siRNA sequences corresponding to mouse SREBP-1c (5′-TAGAGCGAGCGTTGAACTGTATT-3′) and LacZ (5′-CTACACAAATCAGCGATTT-3′) were subcloned into the pU6 vector (Invitrogen) and were used to construct Ad-si-SREBP-1c and Ad-si-LacZ, respectively. INS-1 (3.6 × 106 cells/6-cm2 dish) was infected with Ad-si-RNAs and cultured for 48 h at 37 °C. After the medium was changed, 9-cis-retinoic acid (9-cis-RA) and 22-hydroxycholesterol (22OH-Cho) were added, and culturing was continued for 24 h. Nuclear proteins were extracted, and Western blotting was performed using anti-rabbit SREBP-1 (sc-8984, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-goat PDX-1 (sc-14662, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-goat lamin B (sc-6216, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-rabbit Na,K-ATPase (catalog no. 3010, Cell Signaling) antibodies. Lamin B and Na, K-ATPase antibodies were the control proteins for nuclear and membrane proteins.

Real Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription (RT)-PCR

Real time PCR was performed using StepOneTM real time PCR (Applied Biosystems) with a TaqMan Gene Expression Cells-to-CTTM kit (Ambion). Primers were purchased from Applied Biosystems. The primers used were rat SREBP-1c (Rn01495769-m1), rat PDX-1 (Rn00755591-m1), rat insulin 1 (Rn0212433-g1), and rat β-actin (4352340E). Real time PCR was duplicated for each cDNA sample. Each gene mRNA level was acquired from the value of the threshold cycle (Ct) of real time PCR as related to β-actin.

Statistics

Results are expressed as means ± S.E., and the statistical significance was assessed using F tests and Student's t tests for unpaired data.

RESULTS

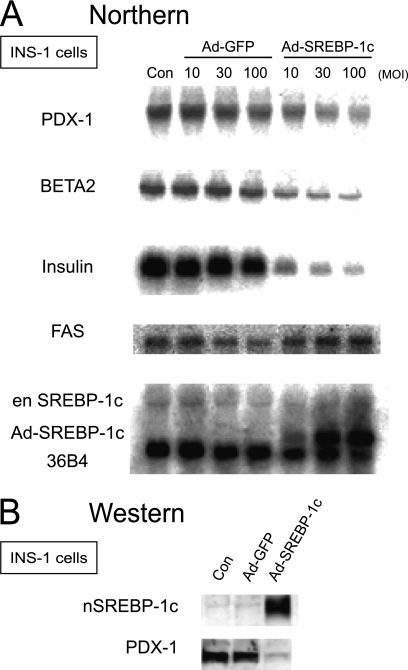

Overexpression of Adenoviral SREBP-1c in INS-1 Cells Inhibits Expression of Insulin and β Cell-specific Transcription Factors

To investigate the inhibitory effect of SREBP-1c on β cell function, rat insulinoma INS-1 cells were infected with Ad-SREBP-1c or Ad-GFP as the negative control (Fig. 1A). Ad-SREBP-1c overexpression increased expression of an SREBP-1c target gene, fatty-acid synthase, in a dose-dependent manner.

FIGURE 1.

SREBP-1 inhibits Pdx-1 mRNA and protein expression. A, INS-1 cells were infected with Ad-human SREBP-1c or Ad-GFP at 10, 30, or 100 multiplicities of infection (MOI) in a 10 mm glucose medium for 48 h. After medium was changed, cells were further cultured for 6 h in 25 mm glucose medium in the absence of adenovirus. Extracted RNA (10 μg) was subjected to electrophoresis. Control (con) represents null adenovirus-infected cells. PDX-1, BETA2, insulin, fatty-acid synthase (FAS), endogenous (en)-SREBP-1c, adenovirus-derived human SREBP-1c, and 36B4 mRNA levels were estimated. B, INS-1 cells nuclear extracts (40 μg) infected with Ad-human SREBP-1c or Ad-GFP at 100 multiplicity of infection were immunoblotted using the anti-SREBP and anti-PDX-1 antibodies. The experiments in A and B were repeated two times with similar results.

In contrast, Pdx-1, Beta2, and insulin mRNAs were markedly decreased with the concomitant suppression of insulin gene expression. Moreover, the PDX-1 protein was notably suppressed by SREBP-1c (Fig. 1B). In β cell-specific SREBP-1c transgenic mice, pdx-1 expression decreased, but it increased in SREBP-1c knock-out mice (supplemental Fig. 1) (22). These data indicate that SREBP-1c suppresses PDX-1 at the mRNA level and could contribute, at least partially, to the inhibitory effect of SREBP-1c on β cell function.

SREBP-1c Suppresses the Endogenous Activity of PDX-1 in β Cells but Not in Non-β Cells

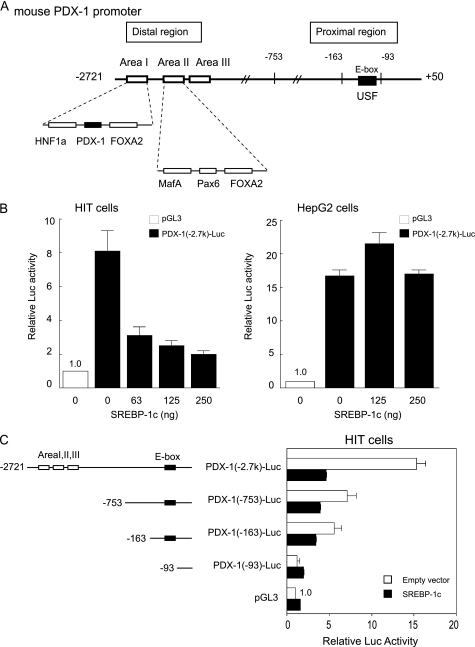

SREBP-1c overexpression in β cells caused impaired insulin secretion, suppression of insulin and pdx-1 expression, and reduction of β cell mass (22, 27). Next, we explored the effect of SREBP-1c on the Pdx-1 promoter. The mouse Pdx-1 extending from −2721 to +50 bp (Fig. 2A) was linked to the luciferase reporter plasmid (PDX-1 (−2.7 k)-Luc) and subjected to a reporter gene assay by transient transfection into hamster insulinoma HIT and non-β HepG2 cells (Fig. 2B). PDX-1 (−2.7 k)-Luc activity was robust in HIT and HepG2 cells (Fig. 2B). SREBP-1c overexpression dose-dependently suppressed the Pdx-1 promoter activity of the 2.7-kb region in HIT cells but not in HepG2 cells (Fig. 2B). This suggested that SREBP-1c probably interacts with β cell-specific endogenous factors and inhibits the Pdx-1 promoter.

FIGURE 2.

SREBP-1c suppresses the endogenous activity of PDX-1 in β cells but not in non-β cells. A, schematic diagram of the −2721 to +50-bp region of the mouse Pdx-1. Organization of distal enhancer/proximal regions shows the key elements and transactivating factors involved in regulation of PDX-1 transcription. B, PDX-1 (−2.7 k)-Luc or the empty vector pGL3-Luc and pSV-β-gal were cotransfected with indicated amounts of CMV-SREBP-1c in HIT (n = 6) and HepG2 cells (n = 6). Luciferase activity was normalized to the pSV-β-gal values. pGL3-Luc activity was set to 1.0. C, various lengths of Pdx-1 promoter luciferase constructs and pSV-β-gal were cotransfected with or without CMV-SREBP-1c (0.125 μg) in HIT cells (n = 3–8). The pGL3-Luc activity of empty vector was set to 1.0. Data are means ± S.E.

SREBP-1c Suppresses PDX-1-Positive Autoregulatory Loop Activity in HIT and HepG2 Cells

Previous studies have identified several transcriptional factors for the Pdx-1 promoter that consists of two important regulatory regions as follows: the proximal and distal enhancer regions (Fig. 2A). In the proximal region, USFs bind to the E-box (32, 33). In the distal enhancer region, located at approximately −1.9 to −2.7 kb, several β cell-specific transcription factor-binding sites have been identified. To delineate the sites responsible for SREBP-1c suppression of Pdx-1, we generated a series of 5′-deletion constructs and analyzed these reporters by transfection into HIT cells (Fig. 2C). In the absence of SREBP-1c, the deletion of sequences from −2721 to −753 bp in PDX-1 (−2.7 k)-Luc reduced the promoter activity by ∼50%, and further truncation of the Pdx-1 promoter from −163 to −93 bp severely attenuated the promoter activity, indicating that both the distal enhancer and proximal regions are required for complete Pdx-1 promoter activity as previously reported (32). SREBP-1c caused 70, 45, and 39% reduction in the activity of the Pdx-1 promoter containing 2721, 753, and 163 fragments, respectively (Fig. 2C). SREBP-1c-mediated inhibition was completely abolished in PDX-1 (−93)-Luc. These data suggested that SREBP-1c inhibition could occur at the distal enhancer and proximal regions (between −163 and −93 bp).

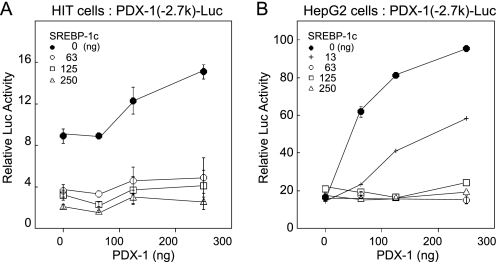

Several β cell-specific transcription factors such as HNF-3β/Foxa2, HNF-1a, Pax6, RIPE3b/Maf, and PDX-1 have been identified in the distal enhancer region (Fig. 2A). In our experimental setting, the 2.7-kb Pdx-1 promoter was activated by HNF-3β/Foxa2 and PDX-1 but not by HNF-1a and RIPE3b/Maf in HIT and HepG2 cells. PDX-1 binds to the enhancer element in area I, suggesting a possible autoregulatory loop (hereinafter referred as auto-loop) as a mechanism for its β cell-specific expression (28, 40). As in vivo evidence for the requirement for a PDX-1 auto-loop mechanism, the mice homozygous for a targeted deletion of the area I–III enhancer region of Pdx-1 (Pdx-1ΔI–III/ΔI–III) had severely impaired pancreas development (41). Heterozygous mice (Pdx-1+/ΔI–III) showed hyperglycemia and reduced insulin secretion (41). Thus, in this study, we focused on the effect of the SREBP-1c on the PDX-1 auto-loop activity. The effects of SREBP-1c on the PDX-1 (−2.7 k)-Luc activities were examined in HIT and HepG2 cells (Fig. 3). In HIT cells, exogenously transfected PDX-1 slightly, but dose-dependently, up-regulated promoter activity, and SREBP-1c inhibited the activity (Fig. 3A). In HepG2 cells lacking endogenous PDX-1, exogenously transfected PDX-1 robustly induced Pdx-1 promoter activity, representing the PDX-1 auto-loop mechanism (Fig. 3B). Intriguingly, in the presence of PDX-1, SREBP-1c suppression that was not observed in HepG2 cells without PDX-1 emerged in a markedly competitive manner. These results demonstrate that SREBP-1c suppresses the PDX-1 auto-loop activity.

FIGURE 3.

SREBP-1c suppresses the PDX-1 auto-loop activity in β and non-β cells. PDX-1 (−2.7k)-Luc or pGL3-Luc and pSV-β-gal were cotransfected with the indicated amounts of CMV-SREBP-1c or CMV-PDX-1 in HIT (n = 6) (A) and HepG2 cells (n = 6) (B). Luciferase activity was normalized to the pSV-β-gal values. The pGL3-Luc activity was set to 1.0. Data are represented as means ± S.E.

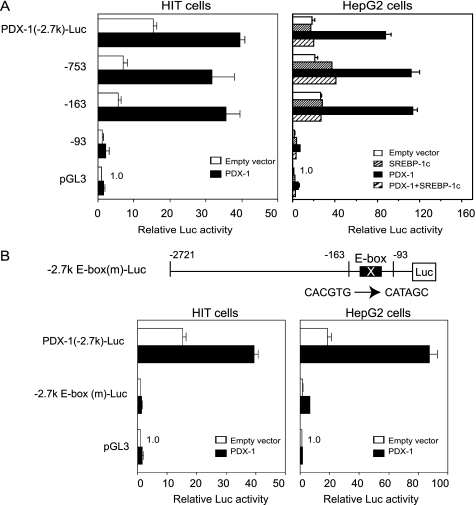

Proximal E-box Is Essential for PDX-1-positive Auto-loop Activity and SREBP-1c Suppression

To determine the essential functioning site for SREBP-1c inhibition of PDX-1 auto-loop activity, a sequential deletion study was performed (Fig. 4A). In HIT cells, PDX-1-Luc-containing fragments from −2721 to −163 bp were activated by exogenous PDX-1 (Fig. 4A) and suppressed to basal levels by SREBP-1c (data not shown). In HepG2 cells, promoters longer than PDX-1 (−93)-Luc were activated by PDX-1 to a similar extent, and SREBP-1c coexpression completely suppressed the activities down to basal levels. PDX-1 (−93)-Luc, which does not contain the E-box at −104 bp, completely lost the PDX-1 auto-loop as well as basal activities in both cell lines (Fig. 4A). These data demonstrate that the PDX-1 auto-loop and SREBP-1c inhibition were mediated primarily through the proximal site between −163 and −91 bp.

FIGURE 4.

E-box in the proximal region is crucial for the PDX-1 auto-loop activity. A, various lengths of Pdx-1 promoter luciferase (Luc) constructs or pGL3-Luc and pSV-β-gal were cotransfected with CMV-PDX-1 (0.25 μg) in HIT cells (n = 6), and CMV-PDX-1 (0.125 μg), CMV-SREBP-1c (0.125 μg), or both in HepG2 cells (n = 6). B, PDX-1 (−2.7 k)-Luc, E-box mutated (−2.7 k)-E-box(m)-Luc, or pGL3-Luc and pSV-β-gal were cotransfected with CMV-PDX-1 (0.25 μg) in HIT cells (n = 6) and CMV-PDX-1 (0.125 μg) in HepG2 cells (n = 6). Luciferase activity was normalized to the pSV-β-gal values. The pGL3-Luc activity was set to 1.0. Data are means ± S.E.

Mutations in the E-box of PDX-1 (−2.7 k) E-box (m)-Luc and (−163) E-box (m)-Luc (data not shown) completely abolished the endogenous activities, and they exhibited no response to exogenous PDX-1 in both cell lines (Fig. 4B), confirming that the E-box in the proximal region is crucial for PDX-1-positive feedback regulation.

PDX-1 and USF1 Directly Interact in the Proximal Region

In the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) using INS-1 and HepG2 nuclear extracts, only USF1 (or USF2) produced a DNA·protein complex in the range of −120 to −90 bp (Fig. 5A). USFs are E-box-binding proteins and important components of the regulatory apparatus (32). Because consensus cis elements for PDX-1 binding were not found in the proximal region from −163 to −93 bp, it is likely that PDX-1 could activate the promoter without DNA binding. Based on data from PDX-1 (−2.7 k) E-box (m)-Luc experiments (Fig. 4B), we examined the protein-protein interaction between USFs and PDX-1 using GST pulldown assays (Fig. 5B). In vitro translated [35S]methionine-labeled USF1 was incubated with GST-PDX-1 fusion proteins or GST alone. 35S-USF1 was pulled down with GST-PDX-1 (FL) and GST-PDX-1 (HD), but not GST-PDX-1 (ΔHD) and GST-PDX-1 (CT) with a deleted HD, indicating that USFs directly interact with the homeodomain of PDX-1.

To estimate the direct association between USFs and PDX-1 on the E-box of the endogenous Pdx-1 promoter of INS-1 cells, we performed ChIP and Re-ChIP assays using E-box primers (Fig. 5C, panels a and b). INS-1 cells were cultured in the absence or presence of 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho in 10 mm glucose. 9-cis-RA is a ligand for RXRs, and 22OH-Cho is a ligand for LXR. LXR·RXR heterodimers activate the SREBP-1c promoter, and these agonists enhance the SREBP-1c expression (42). Immunoprecipitated DNA fragments using IgG, anti-PDX-1, anti-USF1, and anti-USF2 antibodies were quantified by real time PCR. The ChIP assay confirmed USFs binding to the E-box (Fig. 5C, panel c). The results were not affected after SREBP-1c activation by 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho. In the Re-ChIP assay, DNA·protein complexes immunoprecipitated with anti-USF1 and anti-USF2 antibodies were removed from the beads and were re-immunoprecipitated with the anti-PDX-1 antibody or IgG. ChIP and Re-ChIP assays involving sequential immunoprecipitation confirmed the association of USFs with PDX-1 on the E-box. The signal decreased by 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho (Fig. 5C, panel d). These data suggest that PDX-1·USF complex formation on the E-box was involved in the PDX-1 auto-loop activity and that SREBP-1c expression interferes with the association between USFs and PDX-1 on the E-box.

Direct Interaction between SREBP-1c and PDX-1 Interferes with the PDX-1·USF1 Complex and PDX-1 Binding to DNA

Next, we examined the inhibitory effects of SREBP-1c on the PDX-1·USF complex formation on the E-box. SREBP-1c inhibition of the Pdx-1 promoter is mediated through a PDX-1 auto-loop mechanism. Thus, protein-protein interaction between SREBP-1c and PDX-1 may mediate the inhibition. To confirm the interaction in vitro, we performed GST-pulldown assays. In vitro translated [35S]methionine-labeled PDX-1 proteins were incubated with either GST-SREBP-1c (nuclear form) or GST-SREBP-1c (bHLH) (Fig. 6A, panel a). 35S-PDX-1 (FL) and 35S-ΔABC-PDX-1, but not 35S-ΔHD-PDX-1, bound to both GST-SREBP-1c (nuclear) and GST-SREBP-1c (bHLH) (Fig. 6A, panels b and c). Direct interaction of the two proteins was mediated through the bHLH domain of SREBP-1c and the homeodomain of PDX-1. Furthermore, this interaction was confirmed by incubation of GST-PDX-1 proteins with 35S-SREBP-1c (Fig. 6B). GST-SREBP-1c (nuclear) and GST-SREBP-1c (bHLH) were used for homodimerization as positive controls (Fig. 6B). 35S-SREBP-1c bound to both GST-PDX-1 (FL) and GST-PDX-1 (HD) (Fig. 6B). It is important to exclude the possibility that nonspecific nucleic acid bridging was involved in formation of PDX-1·USFs or PDX-1·SREBP-1c (supplemental Fig. 2). To digest the nucleic acids (DNA and RNA), micrococcal nuclease (S7) was used to remove nucleic acids in in vitro translated PDX-1, USF1, and SREBP-1c samples (supplemental Fig. 2A). Both USF-1·PDX-1 and SREBP-1c·PDX-1 binding were not affected by pretreatment with micrococcal nuclease (supplemental Fig. 2, B and C). Thus, the protein interaction between USF-1 (or SREBP-1c) and PDX-1 was specific and does not mediate nonspecific bridging by DNA.

In the distal enhancer region, EMSA analysis showed that potent binding of PDX-1 to the probe containing a PDX-1-binding site in area I (−2517 to −2492 bp) was dose-dependently inhibited by SREBP-1c (Fig. 6C). SREBP-1c did not bind to these probes. The SREBP-1c inhibition was potent as the dissociation of PDX-1 from the probe was still observed by addition of SREBP-1c after the PDX-1 binding to area I (data not shown).

These results suggest that the HD domain of PDX-1 binds to the bHLH domains of USF-1 and SREBP-1c. The binding affinities of the HD domain of PDX-1 to both bHLH proteins was examined using GST-pulldown assays (Fig. 6D). 35S-USF-1·PDX-1 (HD) binding was weakly inhibited by SREBP-1c (Fig. 6D, panel a). In addition, 35S-SREBP-1c·PDX-1 (HD) binding was inhibited by USF-1 (Fig. 6D, panel b). Thus, USF and SREBP-1c complete formation with PDX-1.

PDX-1 Inhibits SREBP Target Genes

We tested whether the formation of the SREBP-1c·PDX-1 complex inhibits the activation of SREBP target genes by SREBPs in HepG2 cells (supplemental Fig. 3, A and B) using LDL receptor (SRE)-Luc or S14 (E-box)-Luc (43). Neither construct has any PDX-1-binding sites. PDX-1, ΔABC-PDX-1, and ΔHD-PDX-1 had no effects on the basal activity of LDL receptor (SRE)-Luc or S14 (E-box)-Luc. LDL receptor (SRE)-Luc activation by SREBP-1a was inhibited with the coexpression of PDX-1 and ΔABC-PDX-1 but not ΔHD-PDX-1. Similar results were obtained in the activation of S14 (E-box)-Luc by SREBP-1aM. Taken together with the data from Fig. 6C, these results suggest that the SREBP-1c·PDX-1 complex has negative effects on both targets. The mutant version ΔHD-PDX-1 is located in the cytosol because of lack of the nuclear localization signal (RRMKWKK) (supplemental Fig. 3, C and D). Thus, the effect on the interaction between ΔHD-PDX-1 and SREBP-1c in the nucleus could not be examined by this approach.

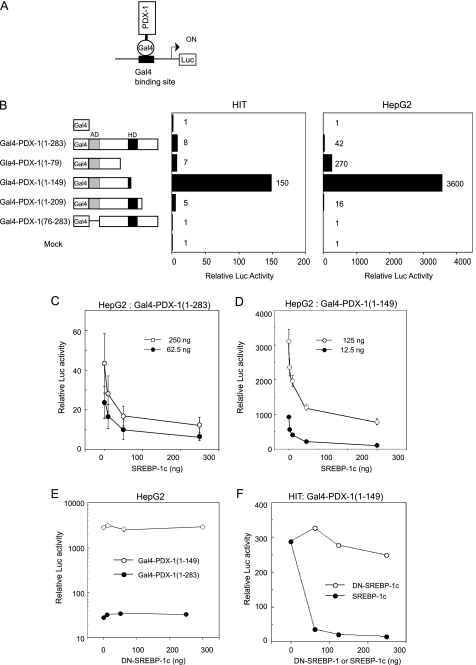

Inactivation of the PDX-1 Auto-loop Requires Transactivation Domain of SREBP-1c

As an alternative approach to that shown in supplemental Fig. 3, we set up a Gal4 fusion protein reporter system to evaluate PDX-1 transactivation and characterize the effects of SREBP-1c (Fig. 7). The Gal4 DNA binding domain (1–147 amino acids) and chimeric Gal4-PDX-1 proteins were expressed in HIT and HepG2 cells, and their transactivities were examined using (Gal4)8-Luc (Fig. 7, A and B). Gal4(1–147) binds to DNA but does not activate transcription because it lacks the activation function. The N terminus of PDX-1, containing three evolutionarily conserved subdomains (activation domain), is critical for transactivation, and HD inhibits transactivation, as described previously (Fig. 7B) (44). SREBP-1c coexpression dose-dependently suppressed the transactivation of Gal4-PDX-1(1–283) as well as Gal4-PDX-1(1–149) (Fig. 7, C and D). DN-SREBP-1(68–453) had no effects on each Gal4-PDX-1 activity (Fig. 7E). DN-SREBP-1 lacks an N-terminal AD domain but contains a bHLH domain (Fig. 8A). These data indicate that the N-terminal AD domain of SREBP-1c is required for PDX-1 inactivation. Similar results were observed in HIT cells (Fig. 7F). SREBP-1c did not directly interact with the N terminus of PDX-1 (Fig. 6B). USF1 had no effect on the transactivation of Gal4-PDX-1(1–283) as well as Gal4-PDX-1(1–149) in both types of cell (data not shown).

FIGURE 7.

SREBP-1c squelches recruitment of PDX-1 coactivators. A, strategy for Gal4-reporter gene assay. B, domain swap experiments. Gal4 DNA-binding domain (1–147 amino acids) is attached to the indicated PDX-1 proteins. Gal4-PDX-1 was cotransfected with pSV-β-gal and (Gal4)8-Luc in HIT or HepG2 cells. The (Gal4)8-Luc activity of the empty expression vector (pM) was set to 1.0. C and D indicated amounts of Gal4-PDX-1(1–283) or Gal4-PDX-1(1–149) and SREBP-1c (0–0.25 μg) were cotransfected with pSV-β-gal and (Gal4)8-Luc in HepG2 cells (n = 6). E, Gal4-PDX-1(1–283) (0.25 μg) or Gal4-PDX-1(1–149) (0.125 μg) and indicated amounts of DN-(Δ1–67)-SREBP-1c were cotransfected with pSV-β-gal and (Gal4)8-Luc in HepG2 cells (n = 3). F, Gal4-PDX-1(1–149) (0.125 μg), SREBP-1c, or DN-(Δ1–67)-SREBP-1c were cotransfected with pSV-β-gal and (Gal4)8-Luc in HIT cells (n = 3). Luciferase activity was normalized to the pSV-β-gal values. The (Gal4)8-Luc activity of the empty expression vector (pM) was set to 1.0 (C–F). Data are means ± S.E. (C and D).

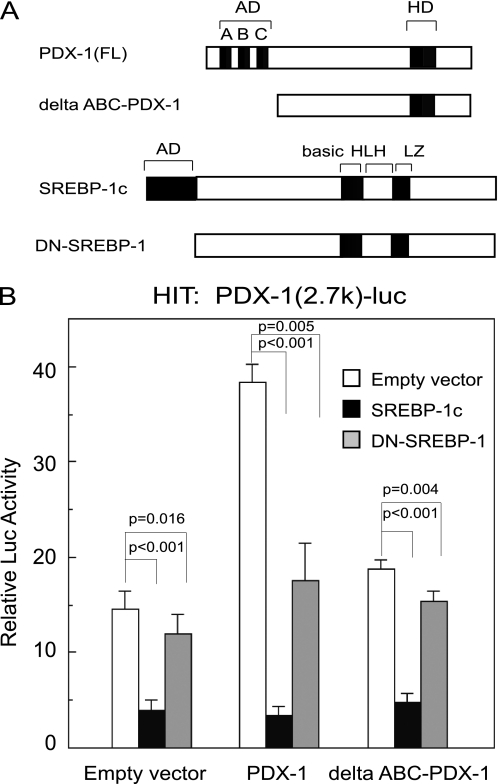

FIGURE 8.

Physical interaction between PDX-1 and SREBP-1c partially contributes to SREBP-1c suppression of the Pdx-1 promoter. A, schematic representation of PDX-1, Δ-ABC-PDX-1, SREBP-1c, and DN-SREBP-1c. Δ-ABC-PDX-1 lacks 75 amino acids in the N-terminal transactivation domain of PDX-1. DN-(Δ-1–67)-SREBP-1c lacks 67 amino acids in N-terminal transactivation domain of SREBP-1c. B, PDX-1 (−2.7 k)-Luc (0.5 μg) or the empty vector pGL3-Luc (0.5 μg) and pSV-β-gal (0.5 μg) were cotransfected with CMV-PDX-1 (0.25 μg), CMV-ΔABC-PDX-1 (0.25 μg), CMV-SREBP-1c (0.25 μg), and CMV-DN-SREBP-1 (0.25 μg) in HIT cells (n = 6). Luciferase activity was normalized to the pSV-β-gal values. The pGL3-Luc activity of empty expression vector (CMV-7) was set to 1.0. Data are means ± S.E. Statistical significance was assessed using the Student's t test for unpaired data.

To clarify the role of the N-terminal AD domain of SREBP-1c, the effects of DN-SREBP-1 and ΔABC-PDX-1 on PDX-1 (2.7 k)-Luc activity were examined in HIT cells (Fig. 8). In the presence of empty vectors, PDX-1 (2.7 k)-Luc activity was inhibited strongly by SREBP-1c but only slightly inhibited by DN-SREBP-1 (p = 0.016) (Fig. 8B). In the presence of exogenous PDX-1, PDX-1 robustly up-regulated PDX-1 (2.7 k)-Luc activity, and SREBP-1c and DN-SREBP-1 reduced the activity by 90 and 50% (p = 0.005), respectively (Fig. 8B). Exogenous ΔABC-PDX-1, which contains an HD domain but lacks an N-terminal AD domain, canceled PDX-1 (2.7k)-Luc activity (Fig. 8B), indicating that the transactivation domain of PDX-1 is involved in the PDX-1 auto-loop. These data suggest that SREBP-1c could interrupt the recruitment of PDX-1 coactivators. Both AD domains of SREBP-1c and PDX-1 are involved in regulation of PDX-1 auto-loop activity (Figs. 7, B and E, and 8B and supplemental Fig. 3).

Induction of the SREBP-1c Protein by LXR·RXR Suppresses PDX-1 Expression

To evaluate physiological relevance, INS-1 cells were cultured with 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho in 10 mm and 25 mm glucose (Fig. 9). 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho are ligands for RXR and LXR, respectively. LXR·RXR heterodimers activate the SREBP-1c promoter (42). Northern blot analysis demonstrated that 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho increased Srebp-1c mRNA, but both Pdx-1 and insulin mRNAs decreased (Fig. 9A). The results of real time PCR supported those of Northern blot analysis (Fig. 9B). Western blot analysis demonstrated that 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho induced the SREBP-1c membrane precursor protein to a great extent accompanied by increased nuclear SREBP-1c maturation, leading to a reduction of PDX-1 (Fig. 9C). In the ChIP assay, endogenous PDX-1, immunoprecipitated by anti-PDX-1 antibody, bound to area I (−2517 to −2492 bp). This binding decreased in 25 mm glucose with 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho (Fig. 9D).

In addition, we investigated whether SREBP-1c knockdown could be reversed by increasing the level of the PDX-1 protein (supplemental Fig. 4). Thus, INS-1 cells were infected with Ad-si-SREBP-1 or Ad-si-LacZ as a control in the absence or presence of 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho and analyzed using real time PCR (supplemental Fig. 4). In the control Ad-si-LacZ-treated cells, 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho induced endogenous SREBP-1c. In the Ad-si-SREBP-1-treated cells, this induction was suppressed by 20% (p = 0.023). SREBP-1c induction significantly reduced Pdx-1 mRNA expression (p = 0.032), but in the Ad-si-SREBP-1-treated cells, Pdx-1 mRNA expression was slightly restored (supplemental Fig. 4A). Western blotting analysis demonstrated that 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho increased the protein levels of membrane precursor and nuclear SREBP-1c in the control Ad-si-LacZ-treated cells, but they were decreased in the Ad-si-SREBP-1c-treated cells. Reduction of PDX-1 expression in the presence of 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho was slightly restored in the Ad-si-SREBP-1c-treated cells (supplemental Fig. 4B).

DISCUSSION

This study clearly demonstrated that SREBP-1c inhibits Pdx-1 promoter activity and represses its gene expression. The activation of SREBP-1c causes β cell dysfunction, including impaired insulin expression and secretion in vitro (INS-1 cells) and in vivo (transgenic mice) (22, 27). In both cases, reduction of PDX-1 was observed and was thought to contribute to β cell dysfunction. To evaluate PDX-1 suppression by SREBP-1c in a more physiologically relevant setting, INS-1 cells were cultured with 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho in 10 and 25 mm glucose media. 9-cis-RA and 22OH-Cho increased SREBP-1c expression and maturation, leading to inhibition of PDX-1 expression at the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 9, A–C). The physiological role of SREBP-1c in PDX-1 expression was confirmed by islets from SREBP-1-null mice and by RIP-nSREBP-1c transgenic mice (supplemental Fig. 1) (22).

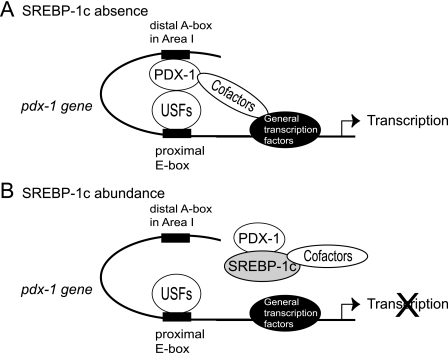

This molecular mechanism operates at the transcription level. Moreover, our data showed that PDX-1 expression is required for SREBP-1c suppression of the Pdx-1 promoter indicating that the target of SREBP-1c is PDX-1 auto-loop activation. To date, this mechanism was reported to operate at the TAAT motif at −2651 to −2648 bp in area I (28). The deletion of area I–III from the endogenous Pdx-1 locus results in severely reduced PDX-1 expression in the pancreas, indicating that this enhancer is crucial for PDX-1 expression in β cells (41). In addition to this distal site confirmed by EMSA and ChIP assays, sequential deletion studies revealed another crucial site for the PDX-1 auto-loop, the proximal E-box. USFs play a key role in the transcription of pdx-1 through this E-box (Fig. 10A) (32, 33). Considering the critical importance of the E-box, but modest stimulation of the Pdx-1 promoter by USF1 cotransfection (data not shown), it has been speculated that the action of USFs is mediated in synergy with another factor (33). Our data indicate that PDX-1 directly binds to USF1 and contributes to the transactivation of the Pdx-1 promoter. In chromatin, PDX-1 may facilitate or stabilize the formation of a large transcription complex by bending DNA by binding to both area I and the USFs/E-box as schematized in Fig. 10A. Other recently identified factors such as HNF3b, MafA, and Foxo1 could also be involved in this complex or mechanism. Using a GST-pulldown assay, we confirmed the direct interaction of HNF-3b·SREBP-1c and HNF-3b·PDX-1 (data not shown).

FIGURE 10.

PDX-1 auto-loop mechanism and SREBP-1c suppression in β cells. A, PDX-1 activates the Pdx-1 promoter as a cofactor interacting with USFs on the E-box and recruits other cofactors. B, SREBP-1c directly binds to PDX-1 and inhibits this auto-loop mechanism in three ways as follows: canceling the binding of PDX-1 to USFs, inhibiting PDX-1 binding in the enhancer region (area I), and squelching the recruitment of cofactors.

Based upon the above notion regarding the PDX-1 auto-loop system, we propose molecular mechanisms by which SREBP-1c inhibits the Pdx-1 promoter in multiple ways. First, SREBP-1c and PDX-1 physically interact through their bHLH and HD, respectively (Fig. 6, A and B). This direct physical interaction could disrupt the PDX-1·USF complex on the E-box that we proposed. SREBP-1c·PDX-1 inhibits PDX-1 binding to area I for the distal enhancer region (Fig. 10B). EMSA and ChIP analysis supports this (Figs. 6C and 9D). The SREBP-1c·PDX-1 complex could also exhibit inhibitory effects on SREBP target genes (supplemental Fig. 3). Second, the Gal4 fusion protein reporter system demonstrated that the AD domain of PDX-1 was crucial for PDX-1 transactivation, and the HD portion with which SREBP interacts was regulatory (Fig. 7B). SREBP-1c strongly and dose-dependently inhibited the transactivation of PDX-1 in this system even in case of the Gal4-PDX-1 fusion protein that does not bind to SREBP-1c, leading us to another important mechanism, i.e. squelching of recruitment of PDX-1 coactivators (Fig. 7D). Consistently, DN-SREBP-1 lacking AD, but retaining the ability to bind to PDX-1, completely lost its inhibitory action on the Gal4-PDX-1 transactivation system (Fig. 7E); DN-SREBP-1 partially suppressed PDX-1's own activation in the PDX-1-luc assay (Fig. 8B). In the Gal4 system, Gal4-PDX-1(1–149) robustly activated the (Gal4)8-Luc, but Gal4-PDX-1(1–263) as well as Gal4-PDX-1(1–209) showed low activity (Fig. 7B). Thus, HD inhibits transactivation. DN-SREBP-1 could not bind to HD because of conformational hindrance or nuclear proteins binding to HD. Therefore, it is concluded that the mechanisms for SREBP-1 suppression of the PDX-1 autoregulatory loop could involve both direct physical interaction and squelching of the recruitment of the cofactors.

Although PDX-1 has been shown to interact with the histone acetyltransferase p300 and cAMP-response element-binding protein-binding protein (CBP) in insulin gene expression (45, 46), SREBP isoforms SREBP-1a and SREBP-2 strongly interact with CBP and p300, but SREBP-1c shows only weak interaction (47, 48). p300 or CBP overexpression did not rescue the inhibition of PDX-1 transactivation by SREBP-1c (data not shown). Frances et al. (49) have reported that PDX-1 physically associates with and recruits the H3-K4 methyltransferase SET9 to the insulin gene. Interaction of PDX-1 with SET9 may be required for the transactivation of the Pdx-1 promoter, and SREBP-1c may squelch the recruitment of SET9 to PDX-1.

35S-SET9 binds not only to GST-SREBP-1c (nuclear form) and GST-SREBP-1c (bHLH) but also to GST-PDX-1 (FL) and GST-PDX-1 (HD) (supplemental Fig. 5). Cofactors like SET9 may be required for the Pdx-1 promoter activity. PDX-1 and SREBP-1c do not function as direct transcription factors but rather as modifiers of other factors. Furthermore, these data suggest that mutual interaction of the two transcription factors could mediate diverse effects on the transactivation of the functional gene.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. A. H. Hasty for critical reading of this manuscript and to Emi Isobe for technical assistance.

This work was supported by research grants from the Japan Foundation of Cardiovascular Research (to M. A.-K.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–5.

- SREBP

- sterol regulatory element-binding protein

- USF

- upstream stimulatory factor

- bHLH

- basic helix-loop-helix

- HD

- homeobox domain

- AD

- activation domain

- RA

- retinoic acid

- 22OH-Cho

- 22-hydroxycholesterol

- RXR

- retinoid X receptor

- LXR

- liver X receptor

- FL

- full length.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ohlsson H., Karlsson K., Edlund T. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 4251–4259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peshavaria M., Gamer L., Henderson E., Teitelman G., Wright C. V., Stein R. (1994) Mol. Endocrinol. 8, 806–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Waeber G., Thompson N., Nicod P., Bonny C. (1996) Mol. Endocrinol. 10, 1327–1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carty M. D., Lillquist J. S., Peshavaria M., Stein R., Soeller W. C. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 11986–11993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bretherton-Watt D., Gore N., Boam D. S. (1996) Biochem. J. 313, 495–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Watada H., Kajimoto Y., Kaneto H., Matsuoka T., Fujitani Y., Miyazaki J., Yamasaki Y. (1996) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 229, 746–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ahlgren U., Jonsson J., Jonsson L., Simu K., Edlund H. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 1763–1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brissova M., Shiota M., Nicholson W. E., Gannon M., Knobel S. M., Piston D. W., Wright C. V., Powers A. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 11225–11232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnson J. D., Ahmed N. T., Luciani D. S., Han Z., Tran H., Fujita J., Misler S., Edlund H., Polonsky K. S. (2003) J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1147–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stoffers D. A., Ferrer J., Clarke W. L., Habener J. F. (1997) Nat. Genet. 17, 138–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stoffers D. A., Stanojevic V., Habener J. F. (1998) J. Clin. Invest. 102, 232–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Melloul D., Marshak S., Cerasi E. (2002) Diabetologia 45, 309–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robertson R. P., Harmon J., Tran P. O., Tanaka Y., Takahashi H. (2003) Diabetes 52, 581–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Poitout V., Robertson R. P. (2002) Endocrinology 143, 339–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. (1997) Cell 89, 331–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shimano H., Horton J. D., Hammer R. E., Shimomura I., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. (1996) J. Clin. Invest. 98, 1575–1584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shimano H., Horton J. D., Shimomura I., Hammer R. E., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. (1997) J. Clin. Invest. 99, 846–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Horton J. D., Shimomura I., Brown M. S., Hammer R. E., Goldstein J. L., Shimano H. (1998) J. Clin. Invest. 101, 2331–2339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shimomura I., Bashmakov Y., Horton J. D. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30028–30032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shimano H. (2007) J. Mol. Med. 85, 437–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ide T., Shimano H., Yahagi N., Matsuzaka T., Nakakuki M., Yamamoto T., Nakagawa Y., Takahashi A., Suzuki H., Sone H., Toyoshima H., Fukamizu A., Yamada N. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 351–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Takahashi A., Motomura K., Kato T., Yoshikawa T., Nakagawa Y., Yahagi N., Sone H., Suzuki H., Toyoshima H., Yamada N., Shimano H. (2005) Diabetes 54, 492–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shimano H., Amemiya-Kudo M., Takahashi A., Kato T., Ishikawa M., Yamada N. (2007) Diabetes Obes. Metab. 9, Suppl. 2, 133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kakuma T., Lee Y., Higa M., Wang Z., Pan W., Shimomura I., Unger R. H. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 8536–8541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ishikawa M., Iwasaki Y., Yatoh S., Kato T., Kumadaki S., Inoue N., Yamamoto T., Matsuzaka T., Nakagawa Y., Yahagi N., Kobayashi K., Takahashi A., Yamada N., Shimano H. (2008) J. Lipid Res. 49, 2524–2534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Iwasaki Y., Iwasaki H., Yatoh S., Ishikawa M., Kato T., Matsuzaka T., Nakagawa Y., Yahagi N., Kobayashi K., Takahashi A., Suzuki H., Yamada N., Shimano H. (2009) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 378, 545–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang H., Maechler P., Antinozzi P. A., Herrero L., Hagenfeldt-Johansson K. A., Bjorklund A., Wollheim C. B. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 16622–16629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marshak S., Benshushan E., Shoshkes M., Havin L., Cerasi E., Melloul D. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 7583–7590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ben-Shushan E., Marshak S., Shoshkes M., Cerasi E., Melloul D. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 17533–17540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Samaras S. E., Cissell M. A., Gerrish K., Wright C. V., Gannon M., Stein R. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 4702–4713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Samaras S. E., Zhao L., Means A., Henderson E., Matsuoka T. A., Stein R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 12263–12270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sharma S., Leonard J., Lee S., Chapman H. D., Leiter E. H., Montminy M. R. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 2294–2299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Qian J., Kaytor E. N., Towle H. C., Olson L. K. (1999) Biochem. J. 341, 315–322 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Taniguchi H., Yamato E., Tashiro F., Ikegami H., Ogihara T., Miyazaki J. (2003) Gene Ther. 10, 15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Amemiya-Kudo M., Shimano H., Yoshikawa T., Yahagi N., Hasty A. H., Okazaki H., Tamura Y., Shionoiri F., Iizuka Y., Ohashi K., Osuga J., Harada K., Gotoda T., Sato R., Kimura S., Ishibashi S., Yamada N. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 31078–31085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Najima Y., Yahagi N., Takeuchi Y., Matsuzaka T., Sekiya M., Nakagawa Y., Amemiya-Kudo M., Okazaki H., Okazaki S., Tamura Y., Iizuka Y., Ohashi K., Harada K., Gotoda T., Nagai R., Kadowaki T., Ishibashi S., Yamada N., Osuga J., Shimano H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 27523–27532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Amemiya-Kudo M., Oka J., Ide T., Matsuzaka T., Sone H., Yoshikawa T., Yahagi N., Ishibashi S., Osuga J., Yamada N., Murase T., Shimano H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34577–34589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ohneda K., Mirmira R. G., Wang J., Johnson J. D., German M. S. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 900–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yoshikawa T., Shimano H., Yahagi N., Ide T., Amemiya-Kudo M., Matsuzaka T., Nakakuki M., Tomita S., Okazaki H., Tamura Y., Iizuka Y., Ohashi K., Takahashi A., Sone H., Osuga Ji J., Gotoda T., Ishibashi S., Yamada N. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1705–1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gerrish K., Cissell M. A., Stein R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 47775–47784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fujitani Y., Fujitani S., Boyer D. F., Gannon M., Kawaguchi Y., Ray M., Shiota M., Stein R. W., Magnuson M. A., Wright C. V. (2006) Genes Dev. 20, 253–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yoshikawa T., Shimano H., Amemiya-Kudo M., Yahagi N., Hasty A. H., Matsuzaka T., Okazaki H., Tamura Y., Iizuka Y., Ohashi K., Osuga J., Harada K., Gotoda T., Kimura S., Ishibashi S., Yamada N. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 2991–3000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Amemiya-Kudo M., Shimano H., Hasty A. H., Yahagi N., Yoshikawa T., Matsuzaka T., Okazaki H., Tamura Y., Iizuka Y., Ohashi K., Osuga J., Harada K., Gotoda T., Sato R., Kimura S., Ishibashi S., Yamada N. (2002) J. Lipid Res. 43, 1220–1235 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Peshavaria M., Henderson E., Sharma A., Wright C. V., Stein R. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 3987–3996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stanojevic V., Habener J. F., Thomas M. K. (2004) Endocrinology 145, 2918–2928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Qiu Y., Guo M., Huang S., Stein R. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 412–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bennett M. K., Toth J. I., Osborne T. F. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 37360–37367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Toth J. I., Datta S., Athanikar J. N., Freedman L. P., Osborne T. F. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 8288–8300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Francis J., Chakrabarti S. K., Garmey J. C., Mirmira R. G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36244–36253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.