Abstract

Most terpenoids have been isolated from plants and fungi and only a few from bacteria. However, an increasing number of genome sequences indicate that bacteria possess a variety of terpenoid cyclase genes. We characterized a sesquiterpene cyclase gene (SGR2079, named gcoA) found in Streptomyces griseus. When expressed in Streptomyces lividans, gcoA directed production of a sesquiterpene, isolated and determined to be (+)-caryolan-1-ol using spectroscopic analyses. (+)-Caryolan-1-ol was also detected in the crude cell lysate of wild-type S. griseus but not in a gcoA knockout mutant, indicating that GcoA is a genuine (+)-caryolan-1-ol synthase. Enzymatic properties were characterized using N-terminally histidine-tagged GcoA, produced in Escherichia coli. As expected, incubation of the recombinant GcoA protein with farnesyl diphosphate yielded (+)-caryolan-1-ol. However, a small amount of another sesquiterpene was also detected. This was identified as the bicyclic sesquiterpene hydrocarbon (+)-β-caryophyllene by comparison with an authentic sample using GC-MS. Incorporation of a deuterium atom into the C-9 methylene of (+)-caryolan-1-ol in an in vitro GcoA reaction in deuterium oxide indicated that (+)-caryolan-1-ol was synthesized by a proton attack on the C-8/C-9 double bond of (+)-β-caryophyllene. Several β-caryophyllene synthases have been identified from plants, but these cannot synthesize caryolan-1-ol. Although caryolan-1-ol has been isolated previously from several plants, the enzyme responsible for its biosynthesis has not been identified previously. GcoA is thus the first known caryolan-1-ol synthase. Isolation of caryolan-1-ol from microorganisms is unprecedented.

Keywords: Bacterial Metabolism, Biosynthesis, Enzyme Kinetics, Enzyme Mechanisms, Secondary Metabolism, Terpenoids, Genome Mining, Streptomyces, Sesquiterpene Cyclase

Introduction

Terpenoids are the largest family of natural products, including over 24,000 known compounds. They have various biological functions and act as flavorings, pigments, antibiotics, hormones, and antitumor agents. Most terpenoids have been isolated from plants and fungi and only a few from bacteria. All terpenoids are derived from the C5 precursors isopentenyl diphosphate and dimethylallyl diphosphate. The successive condensation of isopentenyl diphosphate and dimethylallyl diphosphate gives rise to linear isoprenyl diphosphate precursors of various chain lengths, such as geranyl diphosphate (C10), farnesyl diphosphate (FPP,2 C15), and geranylgeranyl diphosphate (C20). These linear substrates are generally cyclized by terpenoid cyclases to produce the parent skeletons of monoterpenes (C10), sesquiterpenes (C15), diterpenes (C20), and other homologs. Terpenoid cyclases are therefore the first key enzymes in pathways leading to the diverse range of terpenoids. A large number of terpenoid cyclases have been reported from eukaryotes, and these have been studied extensively (1, 2). In contrast, at present there are only a small number of reports of bacterial terpenoid cyclases. Most of the bacterial terpenoid cyclases reported are sesquiterpene cyclases (SCs). Bacterial SCs show no significant amino acid sequence identity with eukaryotic SCs. However, two characteristic metal ion binding motifs are universally conserved among SCs: the aspartate-rich motif (DDXXD/E) and the NSE/DTE motif (N/DDXXS/TXX(K/R)E). These motifs are responsible for the formation of the Mg2+-diphosphate-enzyme complex, as well as the ionization of the substrate (1).

To date, bacterial SCs have only been found in Streptomyces and Nostoc. Germacradienol/geosmin synthases from three Streptomyces species and Nostoc punctiforme PCC 73102 have been characterized (3–6). Geosmin has an earthy odor and is particularly prevalent in actinomycetes, cyanobacteria, and myxobacteria. Germacradienol/geosmin synthase is atypical in that it consists of two terpene cyclase domains. Typical single-domain SCs characterized from Streptomyces and Nostoc include those involved in the synthesis of pentalenene, epi-iso-zizaene, avermitilol, germacrene A, 8a-epi-α-selinene, (−)-δ-cadinene, and (+)-T-muurolol (7–13). However, recent genome sequencing projects have revealed a large number of potential bacterial SC genes. We found more than 80 uncharacterized single-domain SC homolog genes in a variety of bacterial genomes using a BLAST P search with the pentalenene synthase from Streptomyces sp. UC5319 as a query. Many of these homologs show ∼30% amino acid sequence identity to known bacterial SCs, indicating that the homologs may catalyze different reactions to generate a variety of terpenoids. Terpenoids, therefore, seem to be significantly more widely distributed in nature than has been appreciated previously. This prompted us to characterize several previously undescribed bacterial SC homologs.

Recently, we determined the complete genome sequence of Streptomyces griseus IFO13350 (14). We have long researched gene regulation for secondary metabolism and morphological differentiation in this famous streptomycin producer (15). In S. griseus, both secondary metabolism and morphological differentiation are controlled by a microbial hormone, A-factor (2-isocapryloyl-3R-hydroxymethyl-γ-butyrolactone). A-factor gradually accumulates in a growth-dependent manner by the action of AfsA (16). When the A-factor concentration reaches a critical level, A-factor binds the A-factor-specific receptor (ArpA) that is bound to the promoter of adpA and dissociates ArpA from the promoter, resulting in induction of adpA transcription (17). The AraC/XylS family transcriptional regulator AdpA then activates the transcription of many genes that are required for morphological differentiation and secondary metabolism, forming an AdpA regulon (18–20). We found three putative SC genes in the S. griseus genome, in addition to the SGR1269 gene encoding a 2-methylisoborneol (monoterpene) synthase (14, 21). One of these three gene products, SGR6839, consists of two terpene cyclase domains and shows 68% amino acid sequence identity with the germacradienol/geosmin synthase from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2), indicating that SGR6839 is a germacradienol/geosmin synthase. The other two genes encode single-domain SC homologs (SGR2079 and SGR6065). Interestingly, our transcriptome analysis showed that the SGR2079 gene is transcribed in wild-type S. griseus in an AdpA-dependent manner (19), indicating that SGR2079 is involved in the production of one of the secondary metabolites under the control of A-factor. SGR2079 (335 amino acids) shows 29% amino acid sequence identity with the pentalenene synthase from Streptomyces sp. UC5319. Both the aspartate-rich motif (DDEFD, from Asp-83 to Asp-87) and the NSE/DTE motif (NDICSFEKE, from Asn-220 to Glu-228) are conserved. We have characterized the function of SGR2079 in vivo and in vitro. We have revealed that SGR2079 is the first (+)-caryolan-1-ol synthase, and named the SGR2079 gene “gcoA” (S. griseus caryolan-1-ol synthase). (+)-Caryolan-1-ol was detected in the crude cell lysate prepared from wild-type S. griseus, but not from an adpA-deleted mutant, indicating that (+)-caryolan-1-ol is an A-factor-inducible secondary metabolite in S. griseus. Isolation of caryolan-1-ol in microorganisms is unprecedented, although it has been isolated previously from several plants.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

General Analytical Methods

NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 on a JNM-A500 spectrometer (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan), the chemical shifts being given in ppm relative to the solvent peak δH = 7.26 and δC = 77.0 ppm as internal references for 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra, respectively. The coupling constant J was given in Hz. GC-MS analysis was performed using a JEOL JMS-Q1000 GC K9 instrument equipped with an Intercap 5MS/Sil capillary column (15 m × 0.25 mm inside diameter, 0.25 μm film thickness, GL Science, Tokyo, Japan) using the electron impact mode operated at 70 eV. A temperature gradient of 60 (3-min hold) to 260 °C (20 °C min−1) were used. A CP-Chirasil-DEX CB column (10 m × 0.25 mm inside diameter, 0.25 μm film thickness, Varian, Walnut Creek, CA) was used for enantiomer separation using a temperature gradient of 50 (2-min hold) to 190 °C (10 °C min−1). The specific rotation value was measured with a JASCO DIP-1000 digital polarimeter at room temperature.

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, Media, and Chemicals

Escherichia coli strains JM109 and BL21(DE3), plasmids pUC19 and pColdI, restriction enzymes, and other DNA-modifying enzymes used for DNA manipulations were purchased from Takara Biochemicals (Shiga, Japan). S. griseus IFO13350 was obtained from the Institute of Fermentation, Osaka (IFO). Streptomyces lividans TK21 was obtained from D. A. Hopwood. Plasmid pHSA81, used for heterologous expression of gcoA in S. lividans, was obtained from M. Kobayashi. S. lividans and S. griseus were cultured in yeast extract-malt extract medium (glucose, 1%; sucrose, 34%; yeast extract, 0.3%; malt extract, 0.3%; bacto peptone, 0.5%; MgCl2·6H2O, 0.1% (pH 7.0)) and YMPD medium (yeast extract, 0.2%; meat extract, 0.2%; bacto peptone, 0.4%; NaCl, 0.5%; MgSO4·7H2O, 0.2%; glucose, 1% (pH 7.2 )), respectively. FPP was purchased from Sigma. (−)-β-caryophyllene was purchased from TCI (Tokyo, Japan).

Construction of Plasmids

A 1.0-kb DNA fragment containing the gcoA-coding sequence was amplified by PCR using primer I, 5′-CAGAGGTACCAAGCTTATGAGCCAGATCACCTTACCGGCGTTTC-3′ (KpnI site underlined, HindIII site italicized, and the start codon of gcoA shown in boldface) and primer II, 5′-GCCTCTAGACTCGAGTCAGGCGGCGAAGTGCCGGGAC-3′ (XbaI site italicized), and the S. griseus chromosomal DNA as a template. The amplified DNA fragment was cloned between the KpnI and XbaI sites of pUC19, resulting in pUC19-gcoA. The absence of undesired alterations during PCR was confirmed by nucleotide sequencing. The HindIII-XbaI fragment excised from pUC19-gcoA was cloned between the HindIII and XbaI sites of pColdI and pHSA81, resulting in pColdI-gcoA and pHSA81-gcoA, respectively.

Analysis of Terpenoids Produced by Recombinant S. lividans Strains

S. lividans harboring pHSA81-gcoA (or an empty vector pHSA81) was inoculated into yeast extract-malt extract medium (100 ml) containing 5 μg/ml thiostrepton and grown at 30 °C for 72 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0, 20 ml) and then disrupted by sonication. The low molecular weight molecules were then extracted with ethyl acetate from the crude cell lysate. The organic layer was dried with Na2SO4 and evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in ethyl acetate (5 ml) for GC-MS analysis.

Large-scale Preparation and Isolation of Sesquiterpene

The S. lividans strain harboring pHSA81-gcoA was inoculated into yeast extract-malt extract medium (total of 4 liters) containing 5 μg/ml thiostrepton and grown at 30 °C for 96 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0, 500 ml) and then disrupted by sonication. Low molecular weight molecules were then extracted with ethyl acetate from the crude cell lysate. The organic layer was dried with Na2SO4 and evaporated to dryness. The crude materials were dissolved in a small amount of hexane. The sesquiterpene produced was purified by SiO2 column chromatography with hexane:ethyl acetate (100:0 to 100:5) followed by recrystallization in hexane at −20 °C, yielding 6.2 mg of 1. The structure of 1 was determined by NMR using 1H, 13C, distorsionless enhancement by polarization transfer (DEPT), 1H-1H COSY, NOESY, heteronuclear multiple quantum correlation (HMQC), and heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC) experiments, and specific rotation analysis.

Gene Disruption of gcoA in S. griseus

A 2.0-kb region upstream of the Pro-12 codon was amplified by PCR using primer III, 5′-GCGGAATTCTGAACTGCTCGTCCGGGTCTGG-3′ (EcoRI site italicized), and primer IV, 5′-GCGGGATCCCGGCATATGAAACGCCGGTAAG-3′ (BamHI site italicized and the Pro-12 codon shown in boldface), and the S. griseus chromosomal DNA as a template. The amplified fragment was cloned between the EcoRI and BamHI sites of pUC19, resulting in pUC-ΔgcoAN. Similarly, a 2.0-kb region downstream of the Glu-273 codon was amplified by PCR using primer V, 5′-GCGAAGCTTGAACTGATCGAGGAAATCGAGG-3′ (HindIII site italicized and the Glu-273 codon shown in boldface) and primer VI, 5′-GCGAAGCTTTTCGTATCCCTTGACGAAGGAG-3′ (HindIII site italicized). The amplified fragment was cloned into the HindIII site of pUC19, resulting in pUC-ΔgcoAC. The kanamycin resistance gene (aphII) from Tn5 (22) was inserted between the BamHI and HindIII sites of the pUC19-ΔgcoAN, resulting in pUC19-ΔgcoANK. The HindIII fragment excised from the pUC19-ΔgcoAC was cloned in the HindIII site of pUC19-ΔgcoANK, resulting in pUC19-ΔgcoA, in which the middle of the gcoA sequence (encoding Phe-13 to Arg-272) was replaced by the aphII sequence. pUC19-ΔgcoA was linearized with DraI and introduced by protoplast transformation into S. griseus IFO13350. Kanamycin-resistant transformants were selected, and the gene replacement, as a result of double crossover, was confirmed by PCR amplification.

Examination of Terpenoid Production in S. griseus

The wild-type strain S. griseus, mutant ΔgcoA::aphII and mutant ΔadpA were grown in YMPD medium (100 ml) at 30 °C for 72 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0, 20 ml), then disrupted by sonication. Low molecular weight molecules were then extracted with ethyl acetate from the crude cell lysate. The organic layer was dried with Na2SO4 and then analyzed by GC-MS.

Production and Purification of the Recombinant GcoA Protein

For the production of N-terminally 6× His-tagged GcoA, the E. coli BL21(DE3) strain harboring pColdI-gcoA was inoculated into Luria Bertani medium (200 ml) containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin and grown at 37 °C. After the A600 had reached 0.4, the cells were kept at 15 °C for 30 min. isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (final 10 μm) was added, and the culture was then incubated for 24 h at 15 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in buffer A (50 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm imidazole, and 10% glycerol (pH 8.0), 40 ml) and then disrupted by sonication. The crude cell-free extract was prepared by removal of cell debris by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 20 min. The recombinant protein with a His tag was purified using a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid superflow (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, with the exception that 10% glycerol was added to all buffers. The purified GcoA protein was dialyzed against buffer B (10 mm Tris-HCl and 10% glycerol (pH 8.0)). The purity of the recombinant proteins was checked by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The protein concentration was measured with a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE).

In Vitro Enzyme Assay

The standard reaction mixture consisted of 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm mercaptoethanol, 4.6 μm FPP, and 0.5 μm GcoA in a total volume of 2.5 ml. The reaction mixture, overlaid with hexane (1 ml), was incubated at 30 °C for 4 h. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 0.5 m EDTA (pH 8.0, 200 μl) followed by immediate vortexing for 30 s. The product was extracted with hexane and subjected to GC-MS analysis. For determination of the optimum conditions for the GcoA reaction, an in vitro assay was performed as follows. The standard reaction mixture consisted of 50 mm PIPES (pH 7.5), 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm mercaptoethanol, 4.6 μm FPP, and 50 nm GcoA in a total volume of 2.5 ml. The reaction mixture, overlaid with hexane (1 ml), was incubated at 30 °C for 20 min. The data were obtained from three independent experiments.

Kinetic Analysis

The reaction mixture consisted of 50 mm PIPES (pH 7.5), 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm mercaptoethanol, FPP (0.09 to 4.6 μm), and 33 nm GcoA. The total volume of each reaction mixture was 2.5 ml. Each reaction mixture was incubated at 30 °C for 3 min. Each reaction was terminated by the addition of 0.5 m EDTA (pH 8.0, 200 μl) followed by immediate vortexing for 30 s. The product was extracted with hexane and subjected to GC-MS analysis. We confirmed that the product formation was linear throughout this period. Steady-state parameters were determined by fitting the curve to v = Vmax[S]/(Km + [S]), where Vmax is the maximum rate of metabolism, v is the initial velocity of formation of (+)-caryolan-1-ol (1) by GcoA, and S is the concentration of FPP. The data were obtained from three independent experiments.

Isolation of the Deuterium-labeled (+)-Caryolan-1-ol Generated by the in Vitro GcoA Reaction in Deuterium Oxide

The reaction mixture consisted of 50 mm PIPES (pH 7.5), 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm mercaptoethanol, 28.8 μm FPP, 2.5 μm GcoA, and 91.5% D2O. The total volume of the reaction mixture was 200 ml. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30 °C for 18 h. The product was extracted with hexane and then purified by SiO2 column chromatography with hexane:ethyl acetate (100:0 to 100:5), yielding 1.1 mg of deuterium-labeled (+)-caryolan-1-ol.

Synthesis of (−)-Caryolan-1-ol

(−)-Caryolan-1-ol was chemically synthesized according to a method described previously (23).

Spectroscopic Data of (+)-Caryolan-1-ol Generated by GcoA

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.88 (s, 3H, Me-13), 1.00 (s, 3H, Me-15), 1.01 (s, 3H, Me-14), 1.03 (d, 1H, H-12, J = 13.0 Hz), 1.04 (ddd, 1H, H-9α, J = 13.0, 12.0, 5.0 Hz), 1.11 (m, 1H, H-7), 1.28 (m, 1H, H-11), 1.32 (m, 1H, H-6), 1.37 (m, 1H, H-9β), 1.48 (m, 1H, H-3α), 1.50 (m, 1H, H-7), 1.51 (m, 1H, H-6), 1.54 (m, 1H, H-3β), 1.61 (m, 1H, H-11), 1.69 (m, 1H, H-10), 1.70 (m, 1H, H-12), 1.76 (m, 1H, H-10), 1.82 (ddd, 1H, H-5, J = 14.5, 12.0, 7.0 Hz), 2.24 (ddd, 1H, H-2, J = 11.9, 10.4, 8.2 Hz); 13C NMR (125 Hz, CDCl3): δ 20.8 (C-15, q), 20.8 (C-10, t), 21.9 (C-6, t), 30.5 (C-14, q), 33.2 (C-13, q), 34.4 (C-3, t), 34.8 (C-8, s), 35.0 (C-4, s), 36.6 (C-7, t), 37.5 (C-9, t), 38.6 (C-11, t), 39.5 (C-2, d), 44.7 (C-5, d), 48.7 (C-12, t), 71.0 (C-1, s). [α]D +3.38 (c 0.31, CHCl3).

RESULTS

In Vivo Terpenoid Production by GcoA in a Recombinant S. lividans Strain

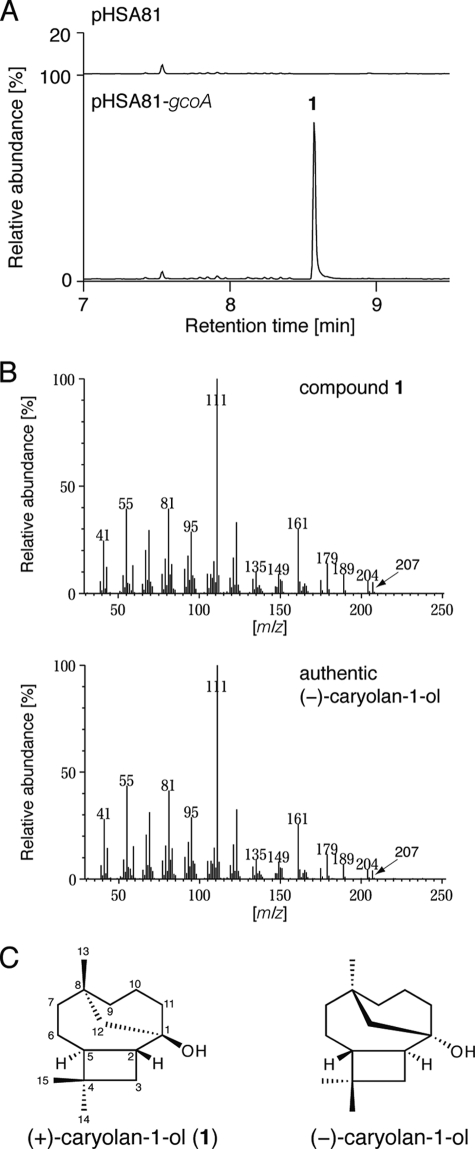

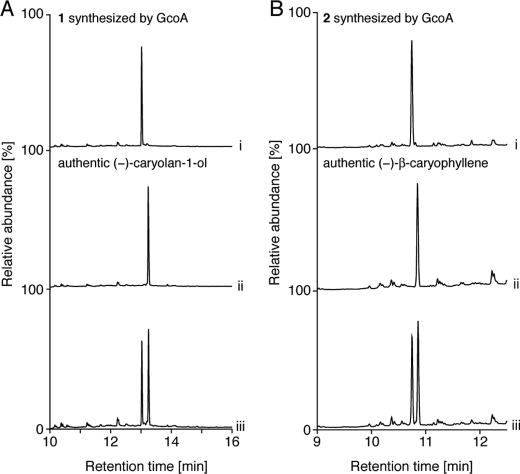

To examine in vivo terpenoid production by GcoA, the gcoA gene was heterologously expressed from a strong promoter in a conventional Streptomyces host, S. lividans. The recombinant S. lividans strain harboring gcoA (or the empty vector pHSA81 as a negative control) was grown at 30 °C for 72 h. Then low molecular weight molecules were extracted from the mycelium using ethyl acetate. When the sample was analyzed by GC-MS, a single major product 1 was detected (Fig. 1A). The MS spectrum of product 1 had peaks at m/z 204 and 207, corresponding to dehydrated (C15H26O-H2O) and demethylated (C15H26O-CH3) forms, respectively, of a sesquiterpene alcohol (Fig. 1B). For structural determination by NMR analysis, product 1 was purified by SiO2 column chromatography followed by recrystallization, yielding 6.2 mg of 1 from the 4-l culture. The 1H NMR spectra displayed signals arising from three fully substituted methyl groups (δ 0.88, 1.00, and 1.01 (each 3H, s)), whereas 16 remaining protons appeared in the region δ 1.03–2.24. The 13C NMR spectrum showed 15 carbon resonances. Directly bound carbon and hydrogen atoms were assigned from the HMQC spectrum. A quaternary carbon signal at δ 71.0 indicated the existence of a tertiary hydroxyl group, whereas the higher field region contained signals for two quaternary carbons, two methine, seven methylene, and three methyl carbons. The structure and relative stereochemistry were determined by COSY, HMBC, and NOESY experiments (supplemental Fig. 1). Product 1 was the tricyclic sesquiterpene alcohol, caryolan-1-ol (Fig. 1C). The NMR spectra of 1 also corresponded well with the reported NMR spectra of (−)-caryolan-1-ol (24). The MS spectrum of authentic (−)-caryolan-1-ol was also almost identical to that of 1 (Fig. 1B). The specific rotation value of 1 was [α]D +3.4, indicating that it was the enantiomeric form of (−)-caryolan-1-ol ([α]D −3.1) (25). To confirm the absolute configuration of 1, it was analyzed by chiral GC-MS (Fig. 2A). The retention time of 1 was different from authentic (−)-caryolan-1-ol, demonstrating that the absolute configuration of 1 was (+).

FIGURE 1.

GC-MS analysis of extracts from crude cell lysate of recombinant S. lividans strains. A, GC-MS chromatograms of extracts from crude cell lysate of S. lividans strains harboring empty vector pHSA81 (upper panel) and pHSA81-gcoA (lower panel). B, MS spectra of 1 (upper panel) and authentic (−)-caryolan-1-ol (lower panel). C, chemical structures of (+) and (−)-caryolan-1-ol.

FIGURE 2.

Chiral GC-MS analysis of GcoA reaction products. A, chiral GC-MS chromatograms of 1 (i), authentic (−)-caryolan-1-ol (ii), and a mixture of 1 and authentic (−)-caryolan-1-ol (iii). B, chiral GC-MS chromatograms of 2 (i), authentic (−)-β-caryophyllene (ii), and a mixture of 2 and authentic (−)-β-caryophyllene (iii). The retention times of both 1 and 2 are different from authentic compounds of the (−) form, demonstrating that the absolute configurations of 1 and 2 are (+).

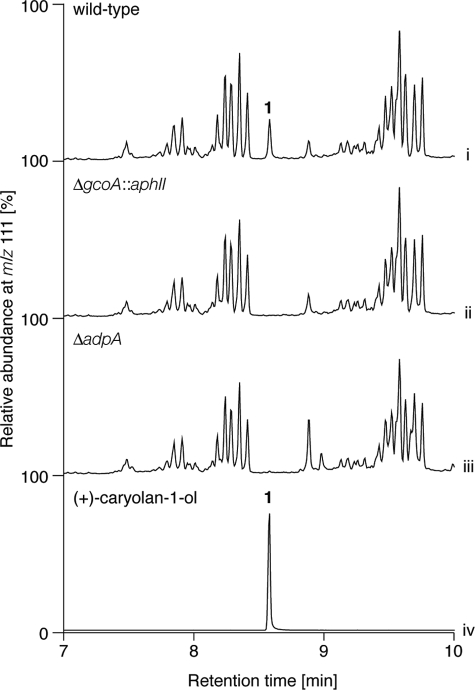

Production of (+)-caryolan-1-ol by Wild-type S. griseus but Not by a gcoA Knockout Mutant or an adpA-deleted Mutant

To examine the function of gcoA in wild-type S. griseus, chromosomal gcoA was inactivated by the insertion of the kanamycin resistance gene aphII. We analyzed the extracts of crude cell lysate of the wild-type and gcoA-disrupted (ΔgcoA::aphII) strains by GC-MS (Fig. 3, i and ii). Because a molecular ion peak with m/z 111 was detected for (+)-caryolan-1-ol (1) (Fig. 1B), production of 1 was assessed by monitoring the molecular ion peak with m/z 111 in the GC-MS analysis (Fig. 3). A peak at 8.58 min was detected in the selected ion chromatogram of the wild-type sample but not in the ΔgcoA::aphII sample. This peak was shown to come from 1 by comparison with the authentic sample using GC-MS (Fig. 3, iv). This confirmed that gcoA was not a cryptic gene and was responsible for (+)-caryolan-1-ol production in S. griseus. Because gcoA was indicated to be a direct target of AdpA (19), a master regulator of secondary metabolism and morphological differentiation in S. griseus, we also analyzed by GC-MS the extracts of crude cell lysate of an adpA-deleted (ΔadpA) mutant (Fig. 3, iii). As we expected, production of 1 was not observed in the ΔadpA mutant, indicating that (+)-caryolan-1-ol (1) is an A-factor-inducible secondary metabolite in S. griseus. (+)-β-Caryophyllene, an intermediate of (+)-caryolan-1-ol synthesis by GcoA (see below), was not detected in wild-type S. griseus.

FIGURE 3.

GC-MS analysis of terpenoids produced by S. griseus. GC-MS chromatograms of the extracts of wild-type S. griseus (i), ΔgcoA::aphII (ii), ΔadpA (iii), and authentic (+)-caryolan-1-ol (iv).

Enzymatic Properties of the Recombinant GcoA Protein

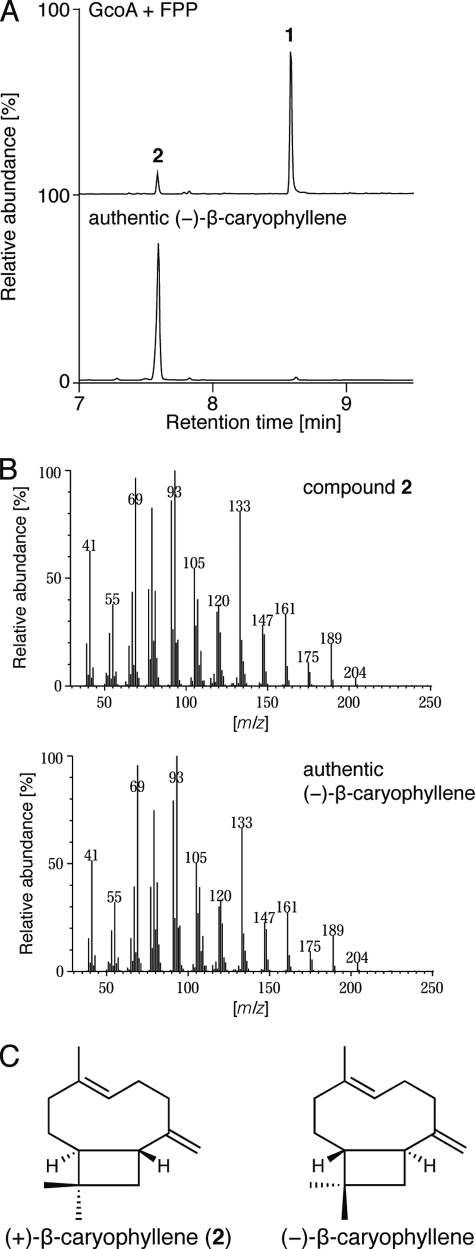

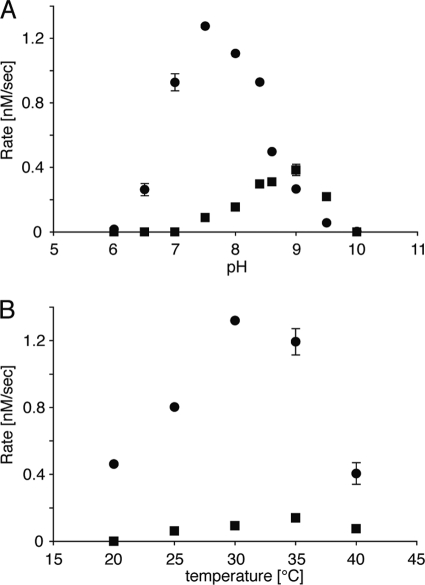

For in vitro analysis, GcoA was produced in E. coli as an N-terminally His-tagged protein with a MNHKVH6IEGRHMELGTLEGSEPKL-GcoA structure. It was purified by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity chromatography to give a single major protein band of 41 kDa on SDS-PAGE. Incubation of purified GcoA with FPP resulted in the production of a major product, 1, and a minor product, 2 (Fig. 4A). 2 was identified as β-caryophyllene in comparison with an authentic sample using GC-MS (Fig. 4, A and B). The chiral GC-MS analysis of 2 synthesized by GcoA showed that the retention time of 2 was different from authentic (−)-β-caryophyllene (Fig. 2B), demonstrating that the absolute configuration of 2 is (+) (see Fig. 4C for structure). We therefore concluded that GcoA is a (+)-caryolan-1-ol (1) synthase that is also capable of producing (+)-β-caryophyllene (2) as a byproduct, at least in vitro. We postulate that GcoA catalyzes (+)-caryolan-1-ol synthesis via formation of (+)-β-caryophyllene, and therefore some portion of the intermediate should come out of the reaction pocket of GcoA. This idea was supported by the observation that the ratio of production rate of (+)-β-caryophyllene to (+)-caryolan-1-ol was greatly affected by pH in the in vitro GcoA reaction (Fig. 5A). When the pH was higher than 9 (probably a nonphysiological pH), the production rate of (+)-β-caryophyllene was higher than that of (+)-caryolan-1-ol. We confirmed that (+)-β-caryophyllene was the intermediate of the (+)-caryolan-1-ol synthesis by the in vitro GcoA reaction in deuterium oxide (D2O), as described below. The optimum pH for (+)-caryolan-1-ol synthesis at 30 °C was 7.5 (Fig. 5A). The optimum temperature for (+)-caryolan-1-ol synthesis at pH 7.5 was 30 °C (Fig. 5B). The GcoA reaction was unable to proceed without MgCl2, and more than 5 mm MgCl2 was required for maximum activity (data not shown). GcoA activity was examined in the presence of other divalent metal ions (5 mm). No activity was observed for Fe2+, Co2+, Zn2+, Ni2+, or Cu2+, but 38% activity (relative to the activity in the presence of Mg2+) was retained in the presence of Mn2+. The Km value for FPP and the kcat value for (+)-caryolan-1-ol formation (at pH 7.5 and 30 °C in the presence of 5 mm MgCl2) were calculated to be 95.6 ± 10.7 nm and 0.025 ± 0.001 s−1, respectively. The kcat/Km values (0.26 s−1μm−1) were broadly comparable with those reported for known bacterial SCs (7, 9, 11, 12).

FIGURE 4.

In vitro reaction of recombinant GcoA protein. A, GC-MS profiles of products generated by GcoA with FPP (upper panel) and authentic (−)-β-caryophyllene (lower panel). B, MS spectra of 2 (upper panel) and authentic (−)-β-caryophyllene (lower panel). C, chemical structures of (+) and (−)-β-caryophyllene.

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of optimum pH and optimum temperature for GcoA reaction. The velocities of (+)-caryolan-1-ol and (+)-β-caryophyllene formations are shown by ● and ■, respectively. A, recombinant GcoA was incubated with FPP at 30 °C at various pHs. 50 mm MES buffer (pH 6.0–6.5), 50 mm PIPES buffer (pH 7.0–7.5), 50 mm 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) buffer (pH 8.0–8.4), and 50 mm N-cyclohexyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (CHES) buffer (pH 8.6–10.0) were used. B, recombinant GcoA was incubated with FPP in 50 mm PIPES buffer (pH 7.5) at various temperatures (20–40 °C).

Analysis of the GcoA Reaction Mechanism

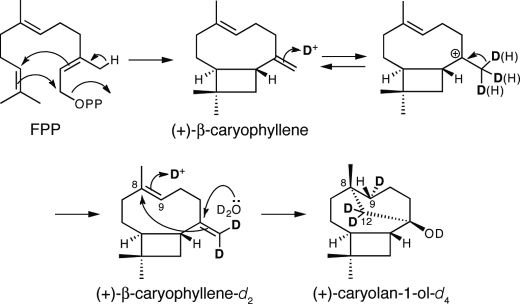

To clarify the GcoA reaction mechanism, we performed an in vitro GcoA reaction in the presence of 91.5% D2O. The GC-MS spectrum of (+)-caryolan-1-ol had peaks at m/z 207 and 210, corresponding to [M-H2O+3]+ and [M-CH3+3]+, respectively, and that of (+)-β-caryophyllene had a peak at m/z 206, corresponding to [M+2]+ (supplemental Fig. 2). To determine the positions of three deuterium atoms in (+)-caryolan-1-ol, a large-scale in vitro assay was performed, and the resulting deuterium-labeled (+)-caryolan-1-ol was isolated by SiO2 column chromatography. 1H and 13C NMR analyses indicated that the positions of deuterium atoms incorporated into (+)-caryolan-1-ol were H-9α (δ 1.04) and H-12 (δ 1.03 and 1.70) (Fig. 6 and supplemental Figs. 3 and 4). Incorporation of a deuterium atom into H-9α indicated that (+)-caryolan-1-ol was synthesized by proton attack on the C-8/C-9 double bond of (+)-β-caryophyllene (Fig. 6). Therefore, judging from the incorporation of two deuterium atoms into H-12 of (+)-caryolan-1-ol, the position of two deuterium atoms in (+)-β-caryophyllene should be in the methylidene moiety (Fig. 6). A possible mechanism of this unexpected labeling is discussed below.

FIGURE 6.

Proposed reactions catalyzed by GcoA in D2O. In vitro GcoA reaction in D2O resulting in the incorporation of three deuterium atoms (D) into (+)-caryolan-1-ol (1) as determined by NMR. The hydroxy group at C-1 of (+)-caryolan-1-ol should also be labeled by deuterium as depicted. However, we confirmed that this deuterium atom was replaced with a hydrogen atom during hexane extraction prior to the GC-MS analysis. Incorporation of a deuterium atom into H-9α indicated that (+)-caryolan-1-ol was synthesized by a proton attack on the C-8/C-9 double bond of (+)-β-caryophyllene. Presumably, (+)-β-caryophyllene is a relatively stable intermediate, and proton attack on the double bond of the methylidene moiety and deprotonation from the resulting methyl group occur repeatedly in the reaction pocket of GcoA.

DISCUSSION

Our genome mining study of putative SC genes resulted in the discovery of (+)-caryolan-1-ol and its synthase GcoA in S. griseus. Caryolan-1-ol has been isolated previously from several plants, including Humulus lupulus, Helichrysum species, Licuala grandis, and Salvia africana-caerulea, as a relatively minor product found by the comprehensive analysis of terpenoids in each plant (26–29). However, the absolute configurations of these caryolan-1-ol compounds, except for the (–)-caryolan-1-ol from Hardwickia pinnata (25), have not been determined, although chemical synthesis of (–)-caryolan-1-ol has been reported (30). This is therefore the first description of (+)-caryolan-1-ol. Moreover, the enzyme responsible for the biosynthesis of caryolan-1-ol has not been identified previously. It has been suggested that caryolan-1-ol is a non-enzymatic product of the bicyclic sesquiterpene hydrocarbon β-caryophyllene, a major sesquiterpene in plants (25). GcoA is thus assumed to be the first known SC that synthesizes caryolan-1-ol.

An in vitro GcoA reaction indicated that GcoA synthesized (+)-β-caryophyllene as a byproduct. β-caryophyllene is a volatile compound found in large quantities in the essential oils of many different spice and food plants, including Origanum vulgare L., Cinnamomum spp., and Piper nigrum L. (31–33). Although the absolute configurations of most of these products have not been described, β-caryophyllene from plants has been believed to have a (−) form. Some liverworts produce “unusual” (+)-β-caryophyllene (34, 35). In bacteria, marine arctic strains of the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides group produce β-caryophyllene, although the absolute configuration has not been determined (36). At least 17 β-caryophyllene synthase genes have been cloned from different plants, and the recombinant enzymes have been characterized (2, 37–41). The β-caryophyllene synthase from Arabidopsis thaliana was confirmed to produce (–)-β-caryophyllene (37), but the absolute configurations of the β-caryophyllenes produced by other enzymes have not been described. In contrast, no β-caryophyllene synthase has been isolated previously from bacteria. Significantly, there has been no report of caryolan-1-ol production by plant β-caryophyllene synthases, indicating that GcoA should be classified differently from these plant β-caryophyllene synthases.

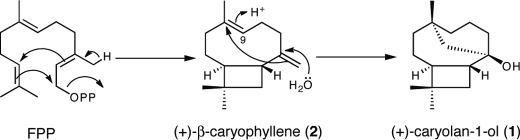

Incorporation of a deuterium atom into the C-9 methylene of (+)-caryolan-1-ol in the in vitro GcoA reaction in D2O confirmed that GcoA produced (+)-caryolan-1-ol via (+)-β-caryophyllene. (+)-caryolan-1-ol should be synthesized by a proton attack on the C-8/C-9 double bond of (+)-β-caryophyllene (Fig. 6). However, incorporation of two deuterium atoms into H-12 of (+)-caryolan-1-ol was unexpected and unaccountable (Fig. 6). Indeed, this indicated that the position of two deuterium atoms in (+)-β-caryophyllene should be in the methylidene moiety (Fig. 6). We have no plausible explanation for the deuterium labeling at the methylidene moiety. However, it should be noted that incubation of (–)-β-caryophyllene in D2O did not yield deuterium-labeled (–)-β-caryophyllene, indicating that the labeling should occur enzymatically (data not shown). We assumed that (+)-β-caryophyllene is a relatively stable intermediate and that proton attack on the double bond of the methylidene moiety and deprotonation from the resulting methyl group occur repeatedly in the reaction pocket of GcoA (Fig. 6). Crystal structure and mutational analysis will be necessary to reveal the molecular mechanism of GcoA in this unique cyclization of FPP. At present, we postulate that GcoA first catalyzes the ionization-initiated cyclization and deprotonation of FPP to yield (+)-β-caryophyllene and then catalyzes the formation of (+)-caryolan-1-ol via protonation of (+)-β-caryophyllene at C-9 to initiate a second cyclization and the addition of a water molecule (Fig. 7). In the GcoA reaction in D2O, the hydroxy group at C-1 of (+)-caryolan-1-ol should be labeled by deuterium, as depicted in Fig. 6. However, we confirmed that this deuterium atom was replaced with a hydrogen atom during hexane extraction prior to the GC-MS analysis (data not shown). Therefore, the GC-MS spectrum of (+)-caryolan-1-ol had a peak at m/z 210, corresponding to [M-CH3+3]+, which pretended that the hydroxy group at C-1 was not labeled by deuterium in the GcoA reaction.

FIGURE 7.

Proposed reactions catalyzed by GcoA. GcoA first catalyzes the ionization-initiated cyclization and deprotonation of FPP to yield (+)-β-caryophyllene (2) and then catalyzes the formation of (+)-caryolan-1-ol (1) via protonation of (+)-β-caryophyllene at C-9 to initiate a second cyclization and the addition of a water molecule.

Several close homologs of gcoA are found in the genomes of some Streptomyces species, such as S. griseus XylebKG-1 (SACT1_2328, 99% identity of amino acid sequences), Streptomyces roseosporus NRRL 15998 (SSGG_05086, 92%), and Streptomyces sp. ACTE (SACTEDRAFT_0826, 85%). These GcoA homologs are presumably (+)-caryolan-1-ol synthases. Our study shows that genome mining is a useful approach in revealing terpenoid diversity in bacteria. Further research into other previously undescribed bacterial SC homologs is now in progress in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Kazuo Furihata for help with NMR analysis.

This work was supported in part by the Targeted Proteins Research Program (TPRP) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan and a Funding Program for Next Generation World-Leading Researchers from the Bureau of Science, Technology, and Innovation Policy, Cabinet Office, Government of Japan.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

- FPP

- farnesyl diphosphate

- SC

- sesquiterpene cyclase

- PIPES

- 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid

- MES

- 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Christianson D. W. (2006) Chem. Rev. 106, 3412–3442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Degenhardt J., Köllner T. G., Gershenzon J. (2009) Phytochemistry 70, 1621–1637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cane D. E., Watt R. M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 1547–1551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cane D. E., He X., Kobayashi S., Omura S., Ikeda H. (2006) J. Antibiot. 59, 471–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ghimire G. P., Oh T. J., Lee H. C., Kim B. G., Sohng J. K. (2008) J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 18, 1216–1220 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Giglio S., Jiang J., Saint C. P., Cane D. E., Monis P. T. (2008) Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 8027–8032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cane D. E., Sohng J. K., Lamberson C. R., Rudnicki S. M., Wu Z., Lloyd M. D., Oliver J. S., Hubbard B. R. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 5846–5857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tetzlaff C. N., You Z., Cane D. E., Takamatsu S., Omura S., Ikeda H. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 6179–6186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lin X., Hopson R., Cane D. E. (2006) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 6022–6023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Takamatsu S., Lin X., Nara A., Komatsu M., Cane D. E., Ikeda H. (2011) Microb. Biotechnol. 4, 184–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chou W. K., Fanizza I., Uchiyama T., Komatsu M., Ikeda H., Cane D. E. (2010) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 8850–8851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Agger S. A., Lopez-Gallego F., Hoye T. R., Schmidt-Dannert C. (2008) J. Bacteriol. 190, 6084–6096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hu Y., Chou W. K., Hopson R., Cane D. E. (2011) Chem. Biol. 18, 32–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ohnishi Y., Ishikawa J., Hara H., Suzuki H., Ikenoya M., Ikeda H., Yamashita A., Hattori M., Horinouchi S. (2008) J. Bacteriol. 190, 4050–4060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Horinouchi S., Beppu T. (2007) Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B 83, 277–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kato J. Y., Funa N., Watanabe H., Ohnishi Y., Horinouchi S. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 2378–2383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ohnishi Y., Kameyama S., Onaka H., Horinouchi S. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 34, 102–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ohnishi Y., Yamazaki H., Kato J. Y., Tomono A., Horinouchi S. (2005) Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 69, 431–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hara H., Ohnishi Y., Horinouchi S. (2009) Microbiology 155, 2197–2210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Akanuma G., Hara H., Ohnishi Y., Horinouchi S. (2009) Mol. Microbiol. 73, 898–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Komatsu M., Tsuda M., Omura S., Oikawa H., Ikeda H. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 7422–7427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beck E., Ludwig G., Auerswald E. A., Reiss B., Schaller H. (1982) Gene 19, 327–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fitjer L., Malich A., Paschke C., Kluge S., Gerke R., Rissom B., Weiser J., Noltemeyer M. (1995) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 9180–9189 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rocha K. A. S., Rodrigues N. V. S., Kozhevnikov I. V., Gusevskaya E. V. (2010) Appl. Catal. A Gen. 374, 87–94 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Misra R., Pandey R. C., Dev S. (1979) Tetrahedron 35, 2301–2310 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tressl R., Engle K. H., Kossa M., Köppler H. (1983) J. Agric. Food Chem. 31, 892–897 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lourens A. C., Reddy D., Başer K. H., Viljoen A. M., Van Vuuren S. F. (2004) J. Ethnopharmacol. 95, 253–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meekijjaroenroj A., Bessière J. M., Anstett M. C. (2007) Flavour Fragr. J. 22, 300–310 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kamatou G. P. P., Van Zyl R. L., Van Vuuren S. F., Figueiredo A. C., Barroso J. G., Pedro L. G., Viljoen A. M. (2008) S. Afr. J. Bot. 74, 230–237 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Barton D. H. R., Bruun T., Lindsey A. S. (1952) J. Chem. Soc. 2210–2219 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mockute D., Bernotiene G., Judzentiene A. (2001) Phytochemistry 57, 65–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jayaprakasha G. K., Jagan Mohan Rao L., Sakariah K. K. (2003) J. Agric. Food Chem. 51, 4344–4348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Orav A., Stulova I., Kailas T., Müürisepp M. (2004) J. Agric. Food Chem. 52, 2582–2586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fricke C., Rieck A., Hardt I. H., König W. A., Muhle H. (1995) Phytochemistry 39, 1119–1121 [Google Scholar]

- 35. König W. A., Bülow N., Fricke C., Melching S., Rieck A., Muhle H. (1996) Phytochemistry 43, 629–633 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dickschat J. S., Helmke E., Schulz S. (2005) Chem. Biodivers. 2, 318–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen F., Tholl D., D'Auria J. C., Farooq A., Pichersky E., Gershenzon J. (2003) Plant Cell 15, 481–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Köpke D., Schröder R., Fischer H. M., Gershenzon J., Hilker M., Schmidt A. (2008) Planta 228, 427–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Abel C., Clauss M., Schaub A., Gershenzon J., Tholl D. (2009) Planta 230, 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Keszei A., Brubaker C. L., Carter R., Köllner T., Degenhardt J., Foley W. J. (2010) Phytochemistry 71, 844–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schilmiller A. L., Miner D. P., Larson M., McDowell E., Gang D. R., Wilkerson C., Last R. L. (2010) Plant Physiol. 153, 1212–1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.