Abstract

p-Hydroxyphenylacetate (HPA) 3-hydroxylase is a two-component flavin-dependent monooxygenase. Based on the crystal structure of the oxygenase component (C2), His-396 is 4.5 Å from the flavin C4a locus, whereas Ser-171 is 2.9 Å from the flavin N5 locus. We investigated the roles of these two residues in the stability of the C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN intermediate. The results indicated that the rate constant for C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN formation decreased ∼30-fold in H396N, 100-fold in H396A, and 300-fold in the H396V mutant, compared with the wild-type enzyme. Lesser effects of the mutations were found for the subsequent step of H2O2 elimination. Studies on pH dependence showed that the rate constant of H2O2 elimination in H396N and H396V increased when pH increased with pKa >9.6 and >9.7, respectively, similar to the wild-type enzyme (pKa >9.4). These data indicated that His-396 is important for the formation of the C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN intermediate but is not involved in H2O2 elimination. Transient kinetics of the Ser-171 mutants with oxygen showed that the rate constants for the H2O2 elimination in S171A and S171T were ∼1400-fold and 8-fold greater than the wild type, respectively. Studies on the pH dependence of S171A with oxygen showed that the rate constant of H2O2 elimination increased with pH rise and exhibited an approximate pKa of 8.0. These results indicated that the interaction of the hydroxyl group side chain of Ser-171 and flavin N5 is required for the stabilization of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN. The double mutant S171A/H396V reacted with oxygen to directly form the oxidized flavin without stabilizing the C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN intermediate, which confirmed the findings based on the single mutation that His-396 was important for formation and Ser-171 for stabilization of the C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN intermediate in C2.

Keywords: Flavin, Monooxygenase, Hydroxylase, Transient Kinetics, Stopped Flow Kinetics, C4a-hydroperoxy-flavin, Enzyme catalysis, Enzyme kinetics, Enzyme mechanisms, Flavin, Flavoproteins, FMN, Kinetics, Pre-steady-state kinetics, Site directed mutagenesis, oxygenase

Introduction

Flavin-dependent monooxygenases incorporate one atom of molecular oxygen into their organic substrates and are involved in a wide variety of biological redox reactions. The enzymes can be classified into six subclasses according to their reactions and amino acid sequences or into two major types according to polypeptide components involved in the reaction (1, 2). Single-component flavoprotein monooxygenases catalyze flavin reduction and substrate oxygenation using single polypeptides, which have been studied for many decades (2, 3). Only in the past decade have two-component monooxygenases received more attention (1–4). They have been found to catalyze flavin reduction and substrate oxidation using separate polypeptides and are important for the metabolism of aromatic and aliphatic compounds in bacteria (4–7); biosynthetic pathways of antibiotics and cancer drugs, such as actinorhodin (8), rebeccamycin (9), violacein (10), enediyne (11), angucycline (12), kijanimicin (13), and kutzneride (14); and bacterial pathogenesis (15). During the past few years, several crystal structures of the oxygenase components of these enzymes have been reported, including HpaB from Thermus thermophilus HB8 (16), LadA from Geobacillus thermodenitrificans NG80–2 (17), RebH from Lechevalieria aerocolonigenes (18, 19), TftD from Burkholderia cepacia AC1100 (20), SMOA from Pseudomonas putida S12 (21), HsaA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (15), KijD3 from Actinomadura kijaniata (22), and ORF36 from Micromonospora carbonacea var. africana (23). Although many x-ray structures of these enzymes are known, only a few enzymes have been investigated for their reaction kinetics, and little is known about the functional roles of residues surrounding the flavin-binding site.

All types of flavin-dependent monooxygenases use a reactive flavin-oxygen adduct intermediate, C4a-hydroperoxyflavin, for oxygenating various compounds (1, 2, 3). In the absence of substrates or under specific conditions, C4a-hydroperoxyflavin eliminates H2O2 to yield oxidized flavin (Fig. 1) without catalyzing the oxygenation. The degree of C4a-hydroperoxyflavin stability in the absence of a substrate varies among different enzymes ranging from rather long half-lives (e.g. bacterial luciferase (t½ = ∼350 s at 4 °C, pH 8.0) (24), cyclohexanone monooxygenase (t½ = ∼300 s at 4 °C, pH 7.2) (25), oxygenase in the biosynthesis pathway of actinorhodin (t½ = ∼1400 s at 4 °C, pH 7.4) (8), and RebH halogenase (t½ = ∼63 h at 4 °C, pH 7.5) (18)) to short half-life intermediates, where the C4a-hydroperoxyflavin is not kinetically stabilized unless a substrate is present (e.g. p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase (26, 27) or 2-methyl-3-hydroxypyridine-5-carboxylic acid monooxygenase (28–30)). Currently, the factors that control the intermediate stability of various monooxygenases are unknown.

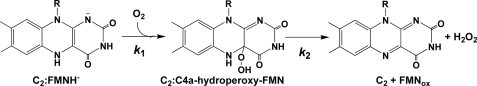

FIGURE 1.

Reaction of a two-component flavin-dependent monooxygenase in the absence of substrate. The first step of the reaction is the formation of a C4a-hydroperoxyflavin intermediate, and the second step is H2O2 elimination to form the oxidized flavin.

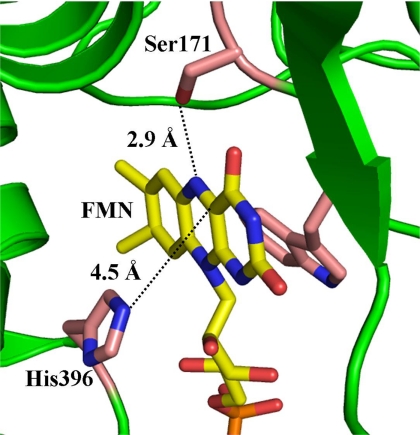

The two-component flavin-dependent monooxygenase, p-hydroxyphenylacetate (HPA)5 3-hydroxylase (HPAH), has well understood reaction kinetics and its intermediate, C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN, has been found to be quite stable (t½ = ∼230 s for the enzyme from Acinetobacter baumannii and t½ = ∼140 s for the enzyme from Pseudomonas aeruginosa) (31–33). The enzyme catalyzes the hydroxylation of HPA to 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetate (DHPA) (5). This enzyme has been identified from various bacterial species and can be grouped into two types based on sequence homology (34). The first type includes HPAHs from P. aeruginosa (33), Escherichia coli (35), T. thermophilus HB8 (16, 36), and Sulfolobus tokodaii strain 7 (37). These enzymes consist of a small reductase (16–20 kDa) and a large oxygenase component (54–59 kDa). A substrate of the oxygenase component (HPA) shows no effect on the flavin reduction, which occurs on the reductase component (33). The other type of enzyme is HPAH from A. baumannii (5, 34), which consists of a larger size reductase (C1) (35.5 kDa), compared with the previously mentioned reductases, and an oxygenase (C2) (47 kDa). In this type of HPAH, HPA binds to the reductase component and acts as an effector, which stimulates the flavin reduction (38), as well as the reduced flavin transfer process from the reductase to the oxygenase (39). A structural comparison of C2 (40) and the oxygenase component of HPAH from T. thermophilus HB8 (HpaB) (16) has indicated that the overall folding of both enzymes belong to the folding of the acyl-CoA dehydrogenase superfamily. However, residues surrounding the flavin-binding site in both enzymes are different. Within a 5-Å distance from the flavin C4a and N5 loci, Ser-171 (2.9 Å from the flavin N5) and His-396 (4.5 Å from the flavin C4a) are present in C2 (40) (Fig. 2), whereas Thr-185 and Arg-100 are present in HpaB (16), with a similar distance but a slightly different geometry. The location of these residues at these strategic positions implies that they should be important for enzyme catalysis.

FIGURE 2.

The active site structures of C2 from A. baumannii. The crystal structure of the C2-FMNH− complex (Protein Data Bank code 2JBS) and amino acid residues ∼5 Å from the flavin (yellow) C4a and N5 loci are shown. For clarity, side chains of residues 120–127 are not shown.

The rate constant for H2O2 elimination in the C2 wild type increases upon an increase in pH and is associated with a pKa > 9.4; one of the speculations about this pKa is that it may belong to His-396, which may act as a general base to assist in the deprotonation of the N5-H to generate H2O2 (step 2 in Fig. 1) (31, 40). Alternatively, this pKa may reflect the pKa of the overall H2O2 elimination process, without the involvement of His-396 (31). Recently, a study on pyranose 2-oxidase, a flavin oxidase that stabilizes C4a-hydroperoxyflavin as a reaction intermediate, has shown that the N5-H bond breakage controls the overall process of the H2O2 elimination (41). Therefore, we investigated the role of His-396 and Ser-171 in the formation and stabilization of the C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN in C2. Our findings indicated that His-396 was important for C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN formation and Ser-171 was important for the stabilization of the C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Site-directed Mutagenesis

The amino acid replacement procedure was performed according to the protocol in the QuikChange® II site-directed mutagenesis kit instruction manual from Stratagene® (La Jolla, CA). pET-11a containing the C2-hpah gene (pET-C2) (34) was used as a template to generate various C2 mutants (H396K, H396R, H396N, H396A, H396V, S171A, S171T, and S171A/H396V) by PCR. The protocol and primers used for generating the mutants are listed in supplemental Table S1.

Expression and Purification

The C2 mutant plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) and grown in 3.6 liters of LB containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin at 37 °C. When the A600 of the culture reached ∼1.0, the incubation temperature was reduced to 25 °C, and isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (final concentration, 1 mm) was added to induce protein expression. The cells continued to grow at 25 °C and were harvested when the A600 = ∼4 (34). The mutant enzymes were purified according to the procedure used for the wild-type enzyme (5, 34), except that no DTT was added to the buffered solutions (34).

Spectroscopic Studies

UV-visible absorbance spectra were recorded with a Hewlett Packard diode array spectrophotometer (HP 8453A) or a Shimadzu 2501PC double-beam spectrophotometer. All of the spectrophotometers were equipped with thermostatted cell compartments.

Stopped Flow Spectrophotometry

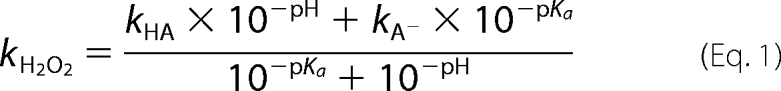

The reactions were performed using a TgK Scientific stopped flow spectrophotometer model SF-61DX2 (Bradford-on-Avon, UK) in single mixing mode. The pathlength of the observation cell was 1.0 cm. Unless specifically mentioned, all of the reactions were performed at 4 °C in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The flow paths of the stopped flow instrument were made anaerobic by leaving overnight with an anaerobic solution of glucose (400 μm), glucose oxidase (15 unit/ml), and 4.8 μg/ml catalase in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) (38). To study the oxidative half-reaction of C2 mutants, an anaerobic enzyme solution was prepared in a glass tonometer by several steps of evacuating and purging with nitrogen that had been passed through an oxygen removal column. C2 was reduced by adding a solution of sodium dithionite (5 mg/ml) to the tonometer via syringe, and the flavin reduction was monitored by a UV-visible spectrophotometer. Alternatively, a reduced enzyme solution was prepared in an anaerobic glovebox (Belle Technology) by adding a solution of sodium dithionite while monitoring the reduction of the enzyme using a UV-visible spectrophotometer inside the glovebox. The resultant reduced enzyme solution was transferred into a glass tonometer. Buffers with various oxygen concentrations (0.13, 0.31, 0.61, and 1.03 mm) were prepared by bubbling buffers with air or standardized O2/N2 gas mixtures. The highest oxygen concentration was achieved by bubbling a buffer with 100% oxygen on ice. Buffers used to vary the pH of the solutions were as follows: 100 mm sodium phosphate for pH 6.0–7.5; 100 mm Tris-HCl for the pH 8.0–8.5; and glycine adjusted with NaOH for pH 9.0–10.0. Observed rate constants of kinetic traces were analyzed according to exponential fits using Program A (developed by C. J. Chiu, R. Chang, J. Diverno, and D. P. Ballou at the University of Michigan). The graphical analysis of rate constants versus oxygen concentration was conducted using Marquardt-Levenberg nonlinear fit algorithms included in the KaleidaGraph software (Synergy Software). The equation used for pH-dependent fits is according to Equation 1,

|

where kH2O2 is an observed rate constant of H2O2 elimination at any pH, kHA is a rate constant of H2O2 elimination at high pH limit, and kA− is a rate constant of H2O2 elimination at low pH limit.

Determination of the Hydroxylation Product (DHPA)

Anaerobic solutions of enzyme, FMN, and HPA in 10 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, were added to a stoichiometric amount of dithionite to generate reduced FMN. The solutions of reduced enzyme and substrate complex (mutant-FMNH−-HPA) were mixed with equal volumes of air-saturated buffers of various pH levels: 100 mm sodium phosphate buffer for pH 6.0 and 7.0, 100 mm Tris-HCl buffer for pH 8.0, and 100 mm glycine buffer for pH 9.0 and 10.0 in closed vessels inside the anaerobic glove box. The reaction mixtures were left for 5 min and then added 0.15 m HCl to quench the reactions. After mixing and before quenching, the reactions contained mutant enzyme (150 μm), FMNH− (75 μm), HPA (2 mm), and oxygen (0.13 mm), and the final pH levels were 6.3, 7.1, 8.0, 9.0, and 10.0 The samples were filtrated by an ultrafiltration device (MicroconTM with molecular mass cut-off of 10 kDa) to remove denatured enzyme and then subjected to HPLC analysis (5, 34).

RESULTS

Expression and Purification of C2 Mutants

Mutant enzymes were expressed and purified using a similar protocol as the wild-type enzyme. Mutant protein yields were ∼30 mg of a purified protein from ∼1 g of cell paste, which was equivalent to ∼300 mg/2 liters of cell culture and were comparable with that of the wild-type enzyme (data not shown). The mutant enzymes exhibited greater than 95% purity without any bound flavin, similar to the wild-type enzyme.

Reaction of the H396R and H396K Mutants with Oxygen

A solution consisting of the H396R or H396K mutant (40 μm) and FMNH− (16 μm) in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was mixed with the same buffer containing various oxygen concentrations using the stopped flow machine. All of the concentrations represent those after mixing. The reactions were monitored by the absorbance changes at wavelengths of 390 and 446 nm (supplemental Fig. S1). For the reaction of the H396R mutant (supplemental Fig. S1A), the kinetic traces showed a monophasic increase of absorbance at 390 nm and 446 nm, consistent with kobs of 1.06 s−1, 1.91 s−1, 3.03 s−1, and 4.05 s−1 from low to high oxygen concentrations, respectively. These kobs were similar to those of the reactions of free FMNH− with various concentrations of oxygen, which were autocatalytic and were approximately one exponential (supplemental Fig. S2) (42). These data indicated that majority of the H396R mutant did not bind to FMNH− under the conditions employed, and the reactions in supplemental Fig. S1A were primarily the oxidation of free FMNH−.

For the reaction of the H396K mutant (supplemental Fig. S1B), the reaction showed three kinetic phases. The first phase (0.002–0.2 s) showed a small increase of absorbance at 390 nm (Δ absorbance unit = ∼0.014), which was dependent on the oxygen concentration with kobs of 2.61, 4.22, 8.82, and 17.15 s−1 for the low to high oxygen concentrations, respectively. The second phase (0.2–4 s) displayed a large increase of absorbance at 390 nm (Δ absorbance unit = ∼0.074) and 446 nm (Δ absorbance unit = ∼0.11), in which the observed rate constants were also dependent on oxygen concentration. The observed rate constants of the second phases were 1.34, 2.35, 3.35, and 3.92 s−1 for the low to high oxygen concentrations, respectively. The third phase (4–100 s) showed a small decrease of absorbance at 390 nm (Δ absorbance unit = ∼0.005) and an increase of absorbance at 446 nm (Δ absorbance unit = ∼0.079), which was independent of oxygen with kobs of 0.09 s−1. Therefore, the first phase was likely the reaction of oxygen with the H396K-FMNH− complex to form the C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN intermediate with a bimolecular rate constant (k1) of 1.5 ± 0.2 × 104 m−1 s−1 (supplemental Fig. S1B). This intermediate eliminated H2O2 to form the oxidized FMN with a rate constant of 9.0 ± 0.2 × 10−2 s−1 during the third phase. The second phase was the reaction of free FMNH− reacting with oxygen to form oxidized FMN (supplemental Figs. S1B and S2). These results indicated that, under the conditions employed, less than 50% of FMNH− bound to H396K. Therefore, a long side chain with a positive charge, such as Arg and Lys, prevented the efficient binding of FMNH− to C2 because both H396R and H396K mutants did not bind well to FMNH−.

Reactions of H396N, H396A, and H396V Mutants with Oxygen

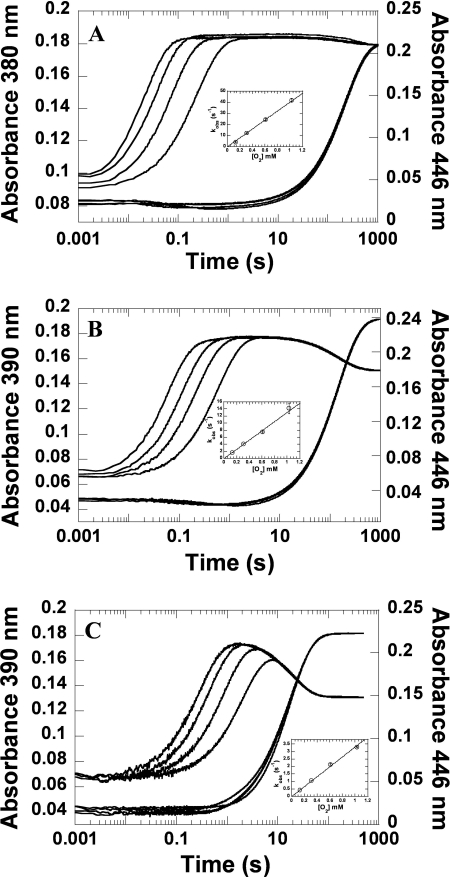

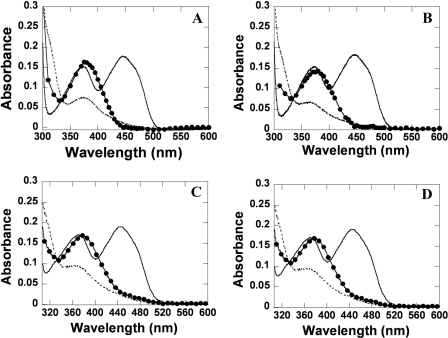

A solution of the reduced H396N mutant was mixed with buffers containing various oxygen concentrations at 4 °C using the stopped flow instrument. For the H396N mutant, the reactions containing H396N (40 μm), FMNH− (16 μm), and oxygen at various concentrations were monitored by absorbance changes at wavelengths of 380 and 446 nm (Fig. 3A), as well as other wavelengths in the region of 370–400 nm (data not shown). The first phase (0.002–1.0 s) exhibited an increase of absorbance at 380 nm (Δ absorbance unit = ∼0.09) without a significant change of absorbance at 446 nm (Fig. 3A). A plot of kobs for this phase (3.87, 12.16, 24.35, and 41.74 s−1) versus the oxygen concentration was linear (Fig. 3A, inset), which was consistent with a bimolecular rate constant of 4.0 ± 0.1 × 104 m−1 s−1 (k1 in Fig. 1). The second phase displayed a small decrease of absorbance at 380 nm and a large increase of absorbance at 446 nm, which corresponded to a rate constant of 4.6 ± 0.1 × 10−3 s−1 (k2 in Fig. 1). A spectrum of the flavin intermediate formed at the reaction time of 1.0 s was obtained by plotting absorbance in the region of 310–600 nm in 5-nm intervals (Fig. 4). The intermediate of the H396N mutant (Fig. 4A) was similar to the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 4D), indicating that the H396N mutant formed C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN similar to the reaction of the C2 wild type (31, 32). These data also indicated that the rate constant for the formation of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN (first phase, k1 in Fig. 1) for the H396N mutant enzyme decreased ∼30-fold, whereas the rate constant for the H2O2 elimination (k2 in Fig. 1) was in a similar range compared with the C2 wild-type enzyme (4.6 × 10−3 versus 3.0 × 10−3 s−1) (Table 1).

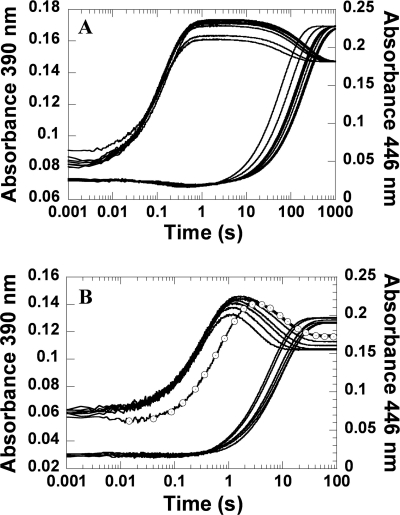

FIGURE 3.

Kinetics of the reactions of reduced His-396 mutants with oxygen. A, solution of 40 μm H396N and 16 μm FMNH− in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was mixed with the same buffer containing various oxygen concentrations (0.13, 0.31, 0.61, and 1.03 mm from the lower to the upper traces) in the stopped flow spectrophotometer at 4 °C. The concentrations given are those after mixing. The reactions were monitored by their absorption changes at 380 and 446 nm. The inset shows a plot of the kobs for the formation of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN monitored from traces at 380 nm versus the oxygen concentrations. A bimolecular rate constant (k1, Fig. 1) of 4.0 ± 0.13 × 104 m−1 s−1 was obtained from slope of the plot. The reactions of H396A (B) and H396V (C) were performed in a similar fashion as the H396N in A, except that the formation and decay of the intermediate was monitored at 390 nm instead of at 380 nm.

FIGURE 4.

Spectra of enzyme species observed during the reactions of His-396 mutants with oxygen. Solutions of the mutant enzymes (40 μm) in a complex with FMNH− (16 μm) in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) were mixed with air-saturated (0.13 mm oxygen) buffers in the stopped flow spectrophotometer. The concentrations quoted represent those after mixing. The reactions were monitored at various wavelengths from 310 to 600 nm, and the data obtained were used for plotting the intermediate spectra (see text). A, H396N. B, H396A. C, H396V; D, C2 wild type (32). The dashed lines represent the reduced enzymes (complexes of His-396 mutant-FMNH−), the solid lines represent oxidized FMN, and the lines with filled circles represent C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN intermediates.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of rate constants for the formation C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN (k1) and the H2O2 elimination step (k2) of wild-type enzyme and His-396 and Ser-171 mutants in stopped flow experiments, such as those shown in Figs. 3 and 7

All of the experiments were performed in 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, at 4.0 °C.

| Enzyme | Rate constant of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN formation (k1) | Rate constant of H2O2 elimination (k2) |

|---|---|---|

| m−1s−1 | s−1 | |

| Wild-typea | 1.1 × 106 | 3.0 × 10−3 |

| H396N | 4.0 ± 0.13 × 104 | 4.6 ± 0.1 × 10−3 |

| H396A | 1.33 ± 0.08 × 104 | 7.0 ± 0.1 × 10−3 |

| H396V | 3.3 ± 0.2 × 103 | 5.7 ± 0.1 × 10−2 |

| S171A | 1.2 ± 0.1 × 105 | 4.37 ± 0.07 |

| S171T | 1.2 ± 0.1 × 106 | 2.5 ± 0.1 × 10−2 |

Reactions of H396A and H396V mutants were conducted in a fashion similar to those of the H396N mutant described above. Reactions of the H396A-FMNH− complex reacting with oxygen resulted in two kinetic phases. The first phase exhibited an increase of absorbance at 390 nm, which was dependent on the concentration of oxygen with a bimolecular rate constant of 1.33 ± 0.08 × 104 m−1 s−1 (Fig. 3B and Table 1). The second phase exhibited a small decrease of absorbance at 390 nm and a large increase of absorbance at 446 nm with an observed rate constant of 7.0 ± 0.1 × 10−3 s−1, which was independent of the oxygen concentration (Fig. 3B). Plotting absorbance in the region of 310–600 nm at the reaction time of 1.0 s resulted in a spectrum of the reaction intermediate formed after the first phase (Fig. 4B). The intermediate spectrum resembled the spectra of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN formed in the reaction of wild-type and H396N enzymes (Fig. 4, A and D). Therefore, the H396A-FMNH− complex reacted with oxygen to form C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN with a rate constant of 1.33 ± 0.08 × 104 m−1 s−1 (Table 1), which was ∼100-fold less than the value of the wild-type enzyme. The intermediate in this enzyme eliminated H2O2 with a rate constant of 7.0 ± 0.1 × 10−3 s−1 (Table 1). Likewise, the data in Figs. 3C and 4C indicated that the H396V-FMNH− complex reacted with oxygen to form C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN with a rate constant of 3.3 ± 0.2 × 103 m−1 s−1 (∼300-fold slower than the wild-type enzyme), and the intermediate in the H396V mutant eliminated H2O2 to form oxidized FMN with a rate constant of 5.7 ± 0.1 × 10−2 s−1 (Table 1), which was ∼19-fold faster that the wild-type enzyme. These data indicated that His-396 was important for the formation of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN in C2.

Effects of pH on the Reaction of H396N-FMNH− and H396V-FMNH− with Oxygen

Based on the previous study (31), the reaction of the C2 wild type with oxygen at various pH values indicated that the formation of the C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN was independent of pH because the value was constant (∼1.1 × 106 m−1 s−1) throughout a range of pH 6.0–10.0. However, the rate constant of the H2O2 elimination from C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN increased upon pH rise and was associated with a pKa value of >9.4. This pKa value was proposed to be associated with the deprotonation of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN at the N5-H to eliminate H2O2 as a leaving group or to belong to the residue acting as a general base in the H2O2 elimination (31). Because His-396 is the only residue in the flavin C4a/N5 area that may act as a general base for this process (40), reactions of H396N and H396V mutants with oxygen at various pH values were investigated.

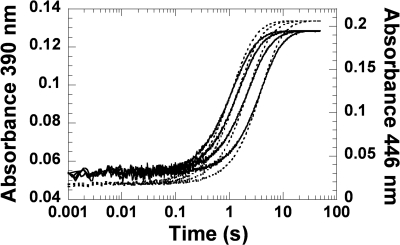

A solution of the H396N-FMNH− or H396V-FMNH− complex in 10 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was mixed with buffers containing oxygen at various pH values using the stopped flow spectrophotometer. Buffers containing oxygen consisted of either 100 mm sodium phosphate for pH 6.0–7.5, 100 mm Tris-HCl for pH 8.0–8.5, or 100 mm glycine for pH 9.0–10.0. After mixing, the reaction solutions containing H396N (40 μm), FMNH− (16 μm), and oxygen (0.13 mm) had final pH values of 6.3, 7.1, 7.6, 8.0, 8.5, 8.8, 9.4, and 10.0. After mixing, the reaction solutions containing H396V (40 μm), FMNH− (16 μm), and oxygen (1.03 mm) had final pH values of 6.2, 6.6, 7.1, 7.5, 8.0, 8.5, 8.8, 9.5, and 10.1. The results (Fig. 5) indicated that the reactions of both mutants at all pH values consisted of two phases. The first phase was the formation of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN, which was indicated by an increase of absorbance at 390 nm, whereas the second phase was the H2O2 elimination from C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN to form the oxidized FMN, as shown by the large absorbance increase at 446 nm (Fig. 5). The observed rate constants for the formation of H396N-C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN (k1 in Fig. 1) were invariable in a pH range of 6.3–10.0 (4.1–5.4 × 104 m−1 s−1) (Fig. 5A and supplemental Table S2), whereas those of H396V-C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN were constant from pH 6.6–10.1 (3.7–4.9 × 103 m−1 s−1) and showed a lower value at pH 6.2 (2.1 × 103 m−1 s−1) (Fig. 5B and supplemental Table S2). The observed rate constants for the second phase (k2 in Fig. 1), which corresponded to the H2O2 elimination from C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN, were pH-dependent in both mutants and the rate constant values increased upon a rise in pH. For the H396N mutant, a rate constant associated with the second phase increased from 4.8 × 10−3 s−1 at pH 6.3 to 1.6 × 10−2 s−1 at pH 10.0 (supplemental Table S2), and a plot of the rate constant values versus pH showed a pKa value of >9.7 (Fig. 6). For the H396V mutant, a rate constant associated with the second phase increased from 0.10 s−1 at pH 6.2 to 0.40 s−1 at pH 10.1 (supplemental Table S2), and a plot of the rate constant values versus pH showed a pKa value of >9.6 (Fig. 6). Although both plots can be fitted with curves associated with pKa values of 9.7 and 9.6, the real pKa values were likely higher than 9.7 and 9.6, because the curves could not reach their saturation because of enzyme denaturation at pH values higher than 10.0.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of pH on the reactions of the His-396 mutants with oxygen. Reactions of reduced His-396 mutants with oxygen at 4 °C in various pH buffers were performed similarly to experiments in Fig. 3 using the stopped flow spectrophotometer. The reactions were monitored at 390 nm to monitor formation of the C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN intermediate (k1) and at 446 nm to monitor formation of the oxidized FMN (k2). A, a solution of H396N (40 μm), FMNH− (16 μm), and oxygen (0.13 mm) at various pH values (see text). B, a solution of H396V (40 μm), FMNH− (32 μm), and oxygen (1.03 mm) at various pH values (see text). Traces of pH 6.0–10 are shown from the upper to the lower traces (390 nm) and the right to the left traces (446 nm) according to low to high pH values. The only exception was the trace of H396V at pH 6.2, which is labeled with empty circles.

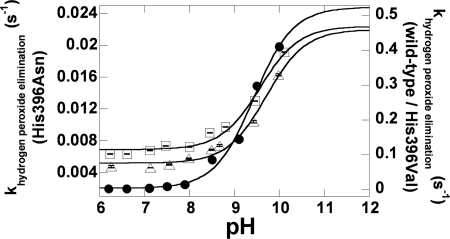

FIGURE 6.

A plot of the observed rate constants for the H2O2 elimination (k2 in Fig. 1) versus pH values. The data were taken from the experiments in Fig. 5. Triangles, squares, and filled circles represent kobs values of both mutants and C2 wild-type enzymes at various pH values. For H396N (triangles), the values of k2 increased from 0.0048 to 0.0163 s−1 for pH 6.3–10.0. For H396V (squares), the values of k2 increased from 0.10 to 0.40 s−1 for pH 6.2–10.1. The theoretical curves associated with pKa values of 9.7 and 9.6 fit well with H396N and H396V data, respectively. For a reference, k2 values of C2 wild-type enzyme (taken from Ref. 31) are shown in filled circles. Data for H396V and C2 wild-type enzymes were plotted according to the right y-axis, whereas those of H396N were plotted according to the left y-axis. Data for the plot are listed in supplemental Table S2.

The results shown in Figs. 5 and 6 indicated that, as in the wild-type enzyme, a pKa of the enzyme-bound reduced flavin for the H396N mutant was lower than 6.3, because the H396N-FMNH− complex reacted with oxygen at the same rate throughout the range of 6.3–10.0 (Fig. 1 and supplemental Table S2). This interpretation was based on work by Bruice (43) and Venkataram and Bruice (44) showing that only the anionic form of the reduced flavin reacted rapidly with oxygen. However, for the H396V mutant, the reaction with oxygen at pH 6.2 was slower than the reactions at pH 6.6–10.0. This result suggested that, at pH 6.2, the reduced flavin bound to H396V may have partly existed as the neutral form, which reacted slower with oxygen and implied that the pKa of reduced FMN bound to H396V was higher than the reduced FMN bound to the C2 wild type or H396N mutant.

Rate constants of the H2O2 elimination from C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN (step 2 in Fig. 1) for H396N and H396V mutants were dependent on pH in a similar fashion to the reaction of the C2 wild type (Fig. 6). Values of pKa associated with this process were >9.4, >9.7, and >9.6 for C2 wild type, H396N, and H396V, respectively (Fig. 6). This result indicates that a pKa of >9.4 in the C2 wild-type reaction (31) is not associated with His-396; in addition, His-396 does not act as a base to initiate the flavin N5-H proton loss. The pKa value observed may have reflected a pKa of the flavin N5-H that controls the overall process of H2O2 elimination (details under “Discussion”).

Reactions of the S171A and S171T with Oxygen

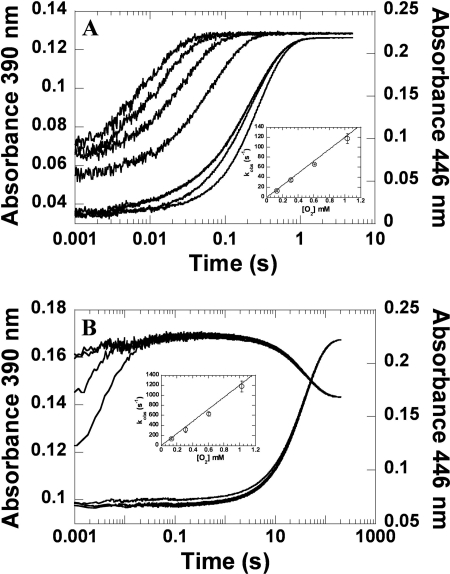

Reactions of S171A-FMNH− and S171T-FMNH− with O2 at pH 7.0 were investigated using stopped flow spectrophotometry at 4 °C. A solution of reduced enzyme (40 μm) and FMNH− (16 μm) in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was mixed with the same buffer containing various concentrations of oxygen. All of the concentrations given represent those after mixing. The reactions were monitored for absorbance changes at wavelengths 390 and 446 nm. The reactions of S171A and S171T exhibited biphasic kinetics (Fig. 7). The first phase, an increase of absorbance at 390 nm, represented the formation of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN and was dependent on the oxygen concentration with bimolecular rate constants of 1.2 ± 0.1 × 105 m−1 s−1 and 1.2 ± 0.1 × 106 m−1 s−1 for the S171A and S171T mutants, respectively (Table 1). The second phase showed a large increase of absorbance at 446 nm and a small decrease of absorbance at 390 nm, representing the H2O2 elimination from C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN to form oxidized FMN (step 2 in Fig. 1) with rate constants of 4.37 ± 0.07 s−1 for S171A and 2.5 ± 0.1 × 10−2 s−1 for S171T. These results indicated that the rate constant for the formation of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN in S171T was very similar to the C2 wild type (1.1 × 106 m−1 s−1) (32), whereas S171A was 11-fold lower. However, rate constants for the H2O2 elimination in both mutants were significantly greater compared with the wild type, ∼1400-fold greater for S171A and ∼8-fold greater for S171T, indicating that Ser-171 was very important for the stabilization of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN in C2. It is possible that in the wild-type enzyme, Ser-171 may make direct contact with the intermediate N5-H, slowing down the H2O2 elimination process (details under “Discussion”).

FIGURE 7.

Kinetics of reactions of the reduced Ser-171 mutants with oxygen. A solution containing Ser-171 mutant (40 μm) and FMNH− (16 μm) in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, was mixed with the same buffer containing various oxygen concentrations at 4 °C using the stopped flow apparatus. All of the concentrations given are those after mixing. The reactions were monitored at 390 and 446 nm. The lower to the upper traces are shown from low to high concentrations of oxygen. A, the reaction of S171A with oxygen. B, the reaction of S171T with oxygen. The insets show the plots of kobs of the C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN formation (k1, Fig. 1) versus the oxygen concentrations. The bimolecular rate constants were calculated from the slopes of the plots as 1.2 ± 0.1 × 105 m−1 s−1 and 1.2 ± 0.1 × 106 m−1 s−1 for S171A and S171T, respectively. The second phase indicated the H2O2 elimination from C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN, which was calculated as 4.37 ± 0.07 s−1 and 2.5 ± 0.1 × 10−2 s−1 for S171A and S171T, respectively.

Effects of pH on the Reaction of S171A-FMNH− with Oxygen

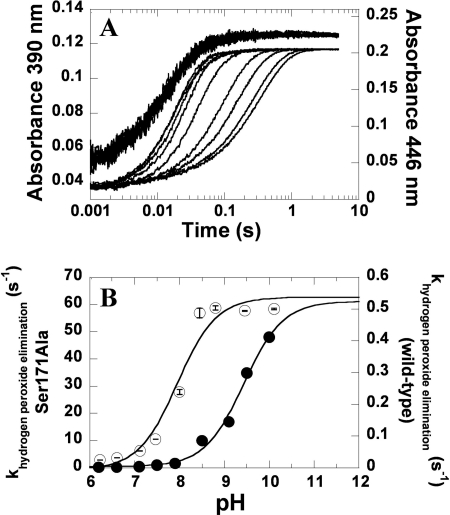

To further explore whether Ser-171 is directly involved with H2O2 elimination from C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN, the effects of pH on the reaction of S171A-FMNH− with oxygen were investigated. Similar to the experiments in Fig. 5, a solution of reduced S171A-FMNH− in 10 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was mixed with buffers of various pH levels containing oxygen. The buffers used were 100 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0–7.5), 100 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0–8.5), and 100 mm glycine buffer (pH 9.0–10.0). After mixing, the reaction containing S171A (40 μm), FMNH− (16 μm), and 0.61 mm oxygen had final pH values of 6.2, 6.6, 7.1, 7.5, 8.0, 8.5, 8.8, 9.5, and 10.1. The results (Fig. 8A) showed that the reaction consisted of two phases. For pH 6.2–7.5, the first phase (0.002–0.05 s) was the formation of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN, as shown by an increase of absorbance at 390 nm and a small lag in absorbance change at 446 nm. The second phase (0.02–1.0 s) was the elimination of H2O2 from C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN, as indicated by a large absorbance change at 446 nm. For the reactions at pH 8.0–10.1, the rate constants pertaining to the formation of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN were still pH-independent; however, the rate constants for the flavin oxidation significantly increased; thus, the kinetics of absorbance change at 390 and 446 nm were very similar, especially at pH 8.5–10.1. This implied that the H2O2 elimination occurred so rapidly for the reaction of S171A at pH greater than 8.5 that little C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN was detected. A plot of observed rate constants for the H2O2 elimination versus pH (Fig. 8B) produced a curve that was significantly different from the plot in Fig. 6, in which the H2O2 elimination process in C2 wild type, H396N, and H396V were all associated with pKa values ∼9.4–9.7. The S171A mutant shifted the pKa of the H2O2 elimination process to be significantly lower than 9.4 and was fitted with a pKa value of 8.0 (Fig. 8B). The pKa value of 8.0 did not reflect the real pKa for the S171A mutant, because at pH 8.0 and above, little of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN was formed, causing a false end point and thus a false pKa. Nevertheless, the data clearly showed that the removal of the H-bond to flavin N5 in the S171A mutant shifted the pKa of the H2O2 elimination process to a significantly lower value compared with 9.4. These data suggest that Ser-171 has a role in the stabilization of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN in C2 and that the interaction of Ser-171 and the flavin N5-H slows the process of H2O2 elimination.

FIGURE 8.

The effect of pH on the reaction of the S171A mutant with oxygen. A, the reactions were performed under similar conditions as those in Fig. 5. After mixing, the final concentrations were 40 μm S171A, 16 μm FMNH−, and 0.61 mm oxygen at various pH values (see text). Kinetic traces monitored at 390 nm in a pH range of 6.2–10.1 were similar to those monitored at 446 nm and are shown from the right to the left, from low to high pH values. B, the observed rate constants for the H2O2 elimination (second phase) from the data in A (empty circles) were plotted against pH, producing a theoretical curve associated with a pKa of 8.0. For reference, the data from the C2 wild-type enzyme are shown as filled circles (31). The data for the plot are listed in supplemental Table S2.

Reaction of the Double Mutant S171A/H396V with Oxygen

To confirm the roles of His-396 and Ser-171 drawn from results of single mutants shown above, reactions of S171A/H396V-FMNH− with oxygen at pH 7.0 were investigated using stopped flow spectrophotometry at 4 °C. After mixing, the reactions containing S171A/H396V (40 μm), FMNH− (16 μm) in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and various oxygen concentrations were monitored at wavelengths of 390 and 446 nm. The results showed a monophasic increase of absorbance at 390 nm, which was synchronized with an increase of absorbance at 446 nm (Fig. 9), indicating that no C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN was detected. The observed rate constants of 0.225, 0.387, 0.593, and 0.761 s−1 were associated with the oxygen concentrations of 0.13, 0.31, 0.61, and 1.03 mm, respectively. When compared with the reaction of the free reduced FMN (FMNH−) with various oxygen concentrations (supplemental Fig. S2), the data showed that the kinetics of the reaction of S171A/H396V with O2 was slower than the reaction of free FMNH− with O2, indicating that FMNH− did bind to the enzyme but that the C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN intermediate did not form in the S171A/H396V mutant.

FIGURE 9.

Kinetics of the double mutant S171A/H396V reaction with oxygen. A solution containing 40 μm S171A/H396V and 16 μm FMNH− in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was mixed with the same buffer containing various oxygen concentrations at 4 °C using the stopped flow apparatus. The reactions were monitored at 390 nm (left axis) and 446 nm (right axis). The lower to the upper traces are shown according to the low to high concentrations of oxygen. The solid lines represent kinetic traces at 390 nm, whereas the dashed lines represent kinetic traces at 446 nm. Kinetic traces at both wavelengths were monophasic and show the same kobs at the same oxygen concentration.

Impact of C4a-Hydroperoxy-FMN Stability on DHPA Formation

To explore whether the decrease in stability of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN can influence product formation, analysis of DHPA formed from reactions of the single mutants (S171A and S171T mutants), and the double mutant (S171A/H396V) was carried out as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The results in Table 2 indicated that no product was detected for the reaction of the double mutant at all pH levels investigated. For the S171T mutant, percentages of DHPA at various pH levels were similar to those of the wild-type enzyme, whereas for the S171A mutant, DHPA formation was lower (∼ 74% at lower pH levels and 16% at pH 10.0). The data suggest that the decrease in stability of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN decreases the efficiency of DHPA formation. For the S171A/H396V double mutant in which the intermediate could not be detected, hydroxylation could not occur.

TABLE 2.

Hydroxylation ratios of S171A and S171T mutants

No DHPA was detected for the reaction of S171A/H396V.

| pH | Percentage of DHPA formed per FMNH− useda |

|

|---|---|---|

| S171A | S171T | |

| 6.3 | 74 ± 3 | 100 ± 3 |

| 7.1 | 74 ± 2 | 104 ± 6 |

| 8.0 | 72 ± 2 | 104 ± 8 |

| 9.0 | 53 ± 4 | 99 ± 4 |

| 10.0 | 16 ± 2 | 76 ± 4 |

a The reactions were performed in triplicate.

DISCUSSION

Our findings here have shown that His-396 and Ser-171 are important for the formation and stabilization, respectively, of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN in C2. Residues similar to His-396 and Ser-171 of C2 were also identified in the active sites of other two-component monooxygenases that are homologous to C2. Based on the structure of the oxygenase component (HpaB) of HPAH from T. thermophilus, the Oγ of Thr-185 is 2.8 Å from the flavin N5 and the guanidyl N of Arg-100 is 4.80 Å from the flavin C4a locus (16). For the oxygenase component (TftD) of chlorophenol 4-monooxygenase from B. cepacia AC1100, Thr-192 is located ∼ 3 Å away from the flavin N5 (20), whereas for the structure of the oxygenase component (HsaA) of HsaAB, the enzymes involved in cholesterol catabolism in M. tuberculosis (15), His-368 and Ser-143 are at positions equivalent to His-396 and Ser-171 in C2. His-101 and Ser-171 were identified as potential catalytic residues in the active site of kijD3 (22, 45). These enzyme structures are shown in supplemental Fig. S3. These data suggest that His-396 and Ser-171 of C2 are conserved and that their functional roles may be prevalent in other two-component flavin-dependent monooxygenases.

Our results (Table 1 and Figs. 3–6) show that His-396 is important for the formation of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN but is less likely to have a direct role in the H2O2 elimination process. Table 1 shows that the rate constants of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN formation in the His-396 mutants are significantly lower than the C2 wild type. Lesser effects were found for the rate constant of the H2O2 elimination step. All mutants bind well to FMNH− except for the H396R and H396K mutants in which the long side chains of Arg and Lys may have caused steric hindrance, which obstructed the flavin binding (supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). The reactions of reduced H396N and reduced H396V with oxygen showed that at all pH values employed, the reduced flavin bound to the mutants was primarily in the anionic form (deprotonated at flavin N1; Fig. 1) and that pKa value of the reduced flavin was lower than 6.0 because rate constants for the formation of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN in both mutants were independent of pH (Fig. 5, similar to the C2 wild type (31). The difference was found for the reaction of reduced H396V at pH 6.0, in which the rate constant for C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN formation was lower than at other pH values (2.1 versus 4.4 × 103 m−1 s−1). In this case, at pH 6.0 the reduced FMN may exist as a neutral form (Fig. 5). According to Bruice (43) and Venkataram and Bruice (44), only the anionic form of the reduced FMN reacts rapidly with oxygen to form a radical pair of flavin semiquinone and superoxide that eventually forms C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN. We also speculate that the effect of His-396 mutation may be on the protonation status of a peroxide group of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN because the reaction of H396N and H396V showed an interesting absorbance decrease of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN at 390 nm with a rise in pH (Fig. 5), in contrast to the C2 wild-type kinetic traces, which did not show any intermediate absorption change at various pH values (31).

The pH-dependent studies of reduced H396N and reduced H396V with oxygen (Figs. 5 and 6) have indicated that His-396 is clearly not a general base involved with the H2O2 elimination process in C2. For both mutants, the rate constants of the H2O2 elimination step (step 2 in Fig. 1) increased upon a rise in pH and were correlated with a pKa of >9.7 for H396N and >9.6 for H396V. These pH dependences are similar to the pattern found for the C2 wild-type enzyme (pKa >9.4). Therefore, His-396 clearly does not act as a general base to assist in the process of H2O2 elimination. In fact, having no base to catalyze the H2O2 elimination, as in this case, is functionally advantageous for the two-component monooxygenase because it helps prolong the lifetime of the C4a-hydroperoxyflavin. This prolonged lifetime helps to reduce the production of wasteful H2O2 when a substrate is absent and ensure efficiency in the hydroxylation in the presence of a substrate. This statement is confirmed by results of DHPA analysis. Stabilization of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN is crucial for DHPA formation because the mutants or conditions with low stability of the intermediate do not promote efficient hydroxylation (Table 2).

Results in Figs. 7–9 and Table 1 clearly show that Ser-171 in C2 is a major residue that stabilizes the C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN. The stabilization energy of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN is most likely contributed by the H-bond interaction at the flavin N5 via Ser-171. A single mutation of Ser-171 to Ala showed a 1400-fold increase for the rate constant of H2O2 elimination, whereas an 8-fold increase was found for the S171T mutant, in which a hydroxyl group side chain was still present. The results from the double mutant S171A/H396V also agree with this conclusion because the double mutant failed to form the C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN intermediate. For the double mutant S171A/H396V, a rate constant of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN formation was predicted to be ∼300-fold lower based on the H396V mutation, and the intermediate decay was predicted to be ∼1400-fold higher based on the S171A mutation. Such effects may cause the rate constant of the intermediate decay to supersede the intermediate formation, preventing kinetic detection of the intermediate. Kinetic traces of Fig. 9 did not show any kinetic detection of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN, confirming the roles of His-396 and Ser-171 proposed, and suggest that a hydroxyl group of Ser-171 is a crucial feature stabilizing C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN.

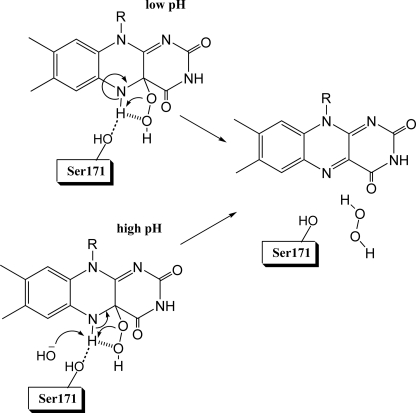

The formation of a hydrogen-bond between the Oγ of Ser-171 and the flavin N5-H is likely a key feature that stabilizes the C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN intermediate in C2 (Fig. 10). Based on the three-dimensional structure of C2, the Oγ atom of Ser-171 is located ∼2.9 Å away from flavin N5. This distance allows the formation of a hydrogen bond between Ser-171 Oγ and flavin N5 (Fig. 2). Recently, studies of pyranose 2-oxidase (41) using transient kinetics and kinetic isotope effects have shown that the bond breakage of the flavin N5-H is the rate-limiting step controlling the overall process of H2O2 elimination from C4a-hydroperoxyflavin. It was proposed that the mechanism of H2O2 elimination involved an intramolecular proton bridge transfer to generate a H2O2 leaving group (Fig. 10) (41). For pyranose 2-oxidase, mutations of Thr-169, a residue that is located ∼3 Å away from the flavin N5 similar to Ser-171 in C2, abolished the formation of C4a-hydroperoxyflavin (46). Based on this view, we predict that the role of Ser-171 in C2 is for the hydrogen bonding interaction with flavin N5-H to impede the deprotonation at the flavin N5-H. At low pH (Fig. 10), elimination of H2O2 may occur via intramolecular proton bridge transfer, similar to the model described for pyranose 2-oxidase reaction (41). For elimination of H2O2 at high pH, a hydroxide ion acts as a specific base to catalyze the process, causing an increase in rate constants as pH increases (Fig. 10).

FIGURE 10.

The model proposed for the stabilization of the C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN intermediate and mechanisms of H2O2 elimination at low and high pH levels. The picture shows a hydrogen bond interaction between the flavin N5 proton and the Ser-171 side chain that impedes the flavin N5-H bond breakage, which in turn obstructs the H2O2 elimination process. At low pH, the H2O2 elimination occurs through an intramolecular hydrogen atom transfer as proposed for pyranose 2-oxidase reaction (41). At higher pH, the H2O2 elimination is faster because the concentration of a hydroxide ion that deprotonates the flavin N5 proton increases, and thus, the rate constant of the process increases.

Studies of pH effects on the reaction of S171A (Fig. 8) also support the role of Ser-171 proposed in Fig. 10 because a pKa-dependent pattern associated with the elimination of H2O2 in the S171A mutant is significantly different from those found for the C2 wild-type enzyme and His-396 mutants (Figs. 6 and 8). However, the pKa values obtained from Figs. 6 and 8 do not reflect the real pKa of the ionizable group (Fig. 10) because the upper limits of the plots could not be reached because of experimental limitations. For the wild-type and His-396 mutant enzymes, conditions at pH greater than 10.0 denatured the enzyme. For the S171A mutant, at pH 8.0 and above, little of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN was formed, causing a false end point. Nevertheless, the data suggest that by removing a hydrogen bonding of Ser-171 and flavin N5, the deprotonation of flavin N5-H and thus H2O2 elimination is more favorable at all pH values compared with the wild-type enzyme.

Assignment of an ionizable group associated with the pH-dependent plots in Figs. 6 and 8 is not definitive based on the current data because the upper limit value could not be reached. One possible interpretation is that, at higher pH, the concentration of hydroxide increases, promoting deprotonation of flavin N5-H in the transition state as depicted in Fig. 10. Thus, the pH-dependent plots in Figs. 6 and 8 do not reflect a pKa of an ionizable group but merely a specific base catalysis. Results in Fig. 8 support this model because the lack of H-bonding at flavin N5 in the S171A mutant would make deprotonation of the flavin N5-H by a specific base easier than in the C2 wild type. The hydrogen bonding interaction between the flavin N5-H and a hydrogen bond acceptor side chain (Fig. 10) may be an important feature for the stabilization of a long-lived C4a-hydroperoxyflavin in other flavin-dependent monooxygenases. The structure of HpaB from T. thermophilus HB8 (2YYI), a two-component enzyme that catalyzes similar hydroxylation as C2 but with sequence identity of only 11.6%, shows that the Oγ of Thr-185, a homologous residue of Ser-171 in C2, is 2.8 angstrom from the flavin N5 (16) supplemental Fig. S3). Although the reaction kinetics of HpaB from T. thermophilus HB8 has not been reported, kinetics of HpaA, the oxygenase component of HPAH from P. aeruginosa, which is similar to HpaB from T. thermophilus (28.5% identity) (33), is known in detail. The results have shown that C4a-hydroperoxyflavin in this enzyme is quite stable, with a rate constant for H2O2 elimination of 0.005 s−1. It is possible that Thr-185 of HpaB is responsible for C4a-hydroperoxyflavin stabilization. The previous study of HPAH from P. aeruginosa also mentioned the possibility that the hydrogen bond to flavin N5 is responsible for stabilization of C4a-hydroperoxyflavin (33). Recently, studies of a flavin-containing monooxygenase have shown that the mutation that alters the H-bond interactions between the flavin N5 and NADP+ also resulted in an enzyme that does not form C4a-hydroperoxyflavin (47). For cyclohexanone monooxygenase in which C4a-hydroperoxyflavin is stabilized (25), the enzyme structure in a complex with NADP+ has shown close interactions between NADP+ and flavin N5 (supplemental Fig. S3) (48). A summary for kinetic constants associated with the H2O2 elimination in various enzymes is shown in supplemental Table S3.

In conclusion, our findings here present experimental evidence showing that the conserved His-396 and Ser-171 in the active site of the oxygenase component of HPAH from A. baumannii (C2) are important for the formation and stabilization of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN. His-396 facilitates the formation of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN and is not involved in the H2O2 elimination process. The hydrogen bonding between Ser-171 and the flavin N5 is a key interaction for prolonging the life time of C4a-hydroperoxy-FMN. The presence of residues homologous to these two residues in the active sites of other two-component monooxygenases implies that their functional roles may be prevalent in other monooxygenases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Barrie Entsch (University of New England, New South Wales, Australia) for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Thailand Research Fund Grant BRG5480001 and a grant from the Faculty of Science, Mahidol University (to P. C.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1–S3 and Figs. S1–S3.

- HPA

- p-hydroxyphenylacetate

- HPAH

- p-hydroxyphenylacetate hydroxylase 3-hydroxylase

- DHPA

- 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetate.

REFERENCES

- 1. van Berkel W. J., Kamerbeek N. M., Fraaije M. W. (2006) J. Biotechnol. 124, 670–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fagan R. L., Palfey B. A. (2010) Comprehensive Natural Products II Chemistry and Biology, Vol. 7, pp. 37–117, Elsevier, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ballou D. P., Entsch B., Cole L. J. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338, 590–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ellis H. R. (2010) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 497, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chaiyen P., Suadee C., Wilairat P. (2001) Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 5550–5561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kirchner U., Westphal A. H., Müller R., van Berkel W. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47545–47553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Otto K., Hofstetter K., Röthlisberger M., Witholt B., Schmid A. (2004) J. Bacteriol. 186, 5292–5302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Valton J., Mathevon C., Fontecave M., Nivière V., Ballou D. P. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 10287–10296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yeh E., Cole L. J., Barr E. W., Bollinger J. M., Jr., Ballou D. P., Walsh C. T. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 7904–7912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Balibar C. J., Walsh C. T. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 15444–15457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lin S., Van Lanen S. G., Shen B. (2008) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 6616–6623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koskiniemi H., Metsä-Ketelä M., Dobritzsch D., Kallio P., Korhonen H., Mäntsälä P., Schneider G., Niemi J. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 372, 633–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang H., White-Phillip J. A., Melançon C. E., 3rd, Kwon H. J., Yu W. L., Liu H. W. (2007) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 14670–14683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heemstra J. R., Jr., Walsh C. T. (2008) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 14024–14025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dresen C., Lin L. Y., D'Angelo I., Tocheva E. I., Strynadka N., Eltis L. D. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22264–22275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim S. H., Hisano T., Takeda K., Iwasaki W., Ebihara A., Miki K. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33107–33117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li L., Liu X., Yang W., Xu F., Wang W., Feng L., Bartlam M., Wang L., Rao Z. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 376, 453–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yeh E., Blasiak L. C., Koglin A., Drennan C. L., Walsh C. T. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 1284–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bitto E., Huang Y., Bingman C. A., Singh S., Thorson J. S., Phillips G. N., Jr. (2008) Proteins 70, 289–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Webb B. N., Ballinger J. W., Kim E., Belchik S. M., Lam K. S., Youn B., Nissen M. S., Xun L., Kang C. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 2014–2027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ukaegbu U. E., Kantz A., Beaton M., Gassner G. T., Rosenzweig A. C. (2010) Biochemistry 49, 1678–1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bruender N. A., Thoden J. B., Holden H. M. (2010) Biochemistry 49, 3517–3524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vey J. L., Al-Mestarihi A., Hu Y., Funk M. A., Bachmann B. O., Iverson T. M. (2010) Biochemistry 49, 9306–9317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Suadee C., Nijvipakul S., Svasti J., Entsch B., Ballou D. P., Chaiyen P. (2007) J. Biochem. 142, 539–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sheng D., Ballou D. P., Massey V. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 11156–11167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Entsch B., Cole L. J., Ballou D. P. (2005) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 433, 297–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Palfey B., Ballou D. P., Massey V. (1995) Active Oxygen in Biochemistry, pp. 37–83, Chapman & Hall, Glasgow, UK [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chaiyen P. (2010) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 493, 62–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chaiyen P., Brissette P., Ballou D. P., Massey V. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 8060–8070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chaiyen P., Brissette P., Ballou D. P., Massey V. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 13856–13864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ruangchan N., Tongsook C., Sucharitakul J., Chaiyen P. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 223–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sucharitakul J., Chaiyen P., Entsch B., Ballou D. P. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 17044–17053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chakraborty S., Ortiz-Maldonado M., Entsch B., Ballou D. P. (2010) Biochemistry 49, 372–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thotsaporn K., Sucharitakul J., Wongratana J., Suadee C., Chaiyen P. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1680, 60–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Galán B., Díaz E., Prieto M. A., García J. L. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 627–636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim S. H., Hisano T., Iwasaki W., Ebihara A., Miki K. (2008) Proteins 70, 718–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Okai M., Kudo N., Lee W. C., Kamo M., Nagata K., Tanokura M. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 5103–5110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sucharitakul J., Chaiyen P., Entsch B., Ballou D. P. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 10434–10442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sucharitakul J., Phongsak T., Entsch B., Svasti J., Chaiyen P., Ballou D. P. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 8611–8623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alfieri A., Fersini F., Ruangchan N., Prongjit M., Chaiyen P., Mattevi A. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 1177–1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sucharitakul J., Wongnate T., Chaiyen P. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 16900–16909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Massey V., Palmer G., Ballou D. P. (1971) Flavins and Flavoproteins, 3rd International Symposium, pp. 349–361, University Park Press, Baltimore [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bruice T. C. (1984) Isr. J. Chem. 24, 54–61 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Venkataram U. V., Bruice T. C. (1984) J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 14, 899–900 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hu Y., Al-Mestarihi A., Grimes C. L., Kahne D., Bachmann B. O. (2008) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 15756–15757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pitsawong W., Sucharitakul J., Prongjit M., Tan T. C., Spadiut O., Haltrich D., Divne C., Chaiyen P. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9697–9705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Orru R., Pazmiño D. E., Fraaije M. W., Mattevi A. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 35021–35028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mirza I. A., Yachnin B. J., Wang S., Grosse S., Bergeron H., Imura A., Iwaki H., Hasegawa Y., Lau P. C., Berghuis A. M. (2009) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 8848–8854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.