Abstract

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) can be coupled with Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) to detect intramolecular dynamics of proteins on the microsecond time scale. Here we describe application of FRET-FCS to detect fluctuations within the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of the Ca2+-signaling protein calmodulin. Intramolecular fluctuations were resolved by global fitting of the two fluorescence autocorrelation functions (green-green and red-red) together with the two cross-correlation functions (green-red and red-green). To match the Förster radius for FRET to the dimensions of the N-terminal and C-terminal domains, a near-infrared acceptor fluorophore (Atto 740) was coupled with a green-emitting donor (Alexa Fluor 488). Fluctuations were detected in both domains on the time scale of 30 to 40 μs. In the N-terminal domain, the amplitude of the fluctuations was dependent on occupancy of Ca2+ binding sites. A high amplitude of dynamics in apo-calmodulin (in the absence of Ca2+) was nearly abolished at a high Ca2+ concentration. For the C-terminal domain the dynamic amplitude changed little with Ca2+ concentration. The Ca2+ dependence of dynamics for the N-terminal domain suggests that the fluctuations detected by FCS in the N-terminal domain are coupled to the opening and closing of the EF-hand Ca2+-binding loops.

Keywords: Calmodulin, Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, FRET, protein dynamics

Proteins function because they can adopt an ensemble of conformations.1-4 Through fluctuations proteins access conformations required for target recognition or ligand binding. Hence, in the so-called “new view” of allostery,2-7 protein motions necessary for function are likely to be present even in the absence of ligands or binding targets.

One of the challenges in studies of protein dynamics is the detection of protein motions on the microsecond time scale. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy8-10 (FCS) is sensitive to fluctuations on the microsecond time scale, and fluorescence signals can be detected with high sensitivity in low-concentration samples. However, detection of dynamics requires sensitivity to protein structure. Although such sensitivity may arise with single fluorophores in certain circumstances due to environmental influences,11-14 Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) provides a general approach.15,16 Coupling of FRET with FCS thus provides sensitivity to intramolecular dynamics.17-20

We recently detected intramolecular dynamics by FRET-FCS in the calcium signaling protein calmodulin (CaM).21 In that work, one fluorophore was attached to the N-terminal lobe of CaM and the other to the C-terminal lobe, allowing detection of inter-lobe fluctuations. Dynamics were detected on the 100-μs time scale in Ca2+ -loaded CaM (holoCaM), but were not detected in the absence of Ca2+ (apoCaM).

In the present application, our objective was to detect dynamics within the N-terminal and C-terminal lobes of CaM. Each lobe of CaM contains EF-handing binding sites for two Ca2+ ions. Ca2+ binding within each lobe is highly cooperative.22,23 Although the two lobes are largely homologous, their Ca2+ binding affinities are not the same. The C-terminal lobe binds Ca2+ with a sub-micromolar Kd value whereas the N-terminal lobe has a micromolar Kd. The kinetics of Ca2+ binding and dissociation differ correspondingly, with Ca2+ off rates of >500 s−1 in the N-terminal lobe and ~10 s−1 in the C-terminal lobe.24,25 Thus, dynamic fluctuations can be expected at these rates or greater within each lobe of CaM.

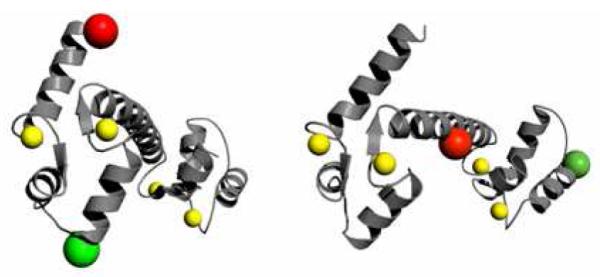

To detect such fluctuations by FRET-FCS, donor and acceptor fluorophores were attached within the N-terminal or C-terminal lobes. The dimensions of the N-terminal and C-terminal lobes of CaM are on the order of 30 Å to 40 Å (protein data bank structures 1prw, 1cll, 1cfd), whereas most dye pairs commonly used for single-molecule FRET measurements have Förster radii R0 of ~50 Å, unsuitable for the shorter dimensions of the N-terminal and C-terminal lobes. We have therefore chosen the dye pair AF 488 – Atto 740, for which the Förster radius is R0 = 34 Å. We detected FRET fluctuations for CaM with both fluorescence labels in the N-terminal lobe or in the homologous C-terminal positions. Figure 1 shows structures of CaM and identifies the labeling sites in the N-terminal and C-terminal domains. For CaM in the absence of Ca2+ the amplitude of the dynamics was markedly larger in the N-terminal lobe than in the C-terminal lobe, consistent with previous computational findings of greater flexibility in the N-terminal domain of apoCaM compared to the C-terminal lobe.26-28 The N-terminal fluctuations were suppressed by Ca2+ binding. In contrast, the amplitude of the C-terminal dynamics was essentially unaltered by Ca2+ binding.

Figure 1.

Structure of holoCaM (pcf 1cll) showing labeling sites. Left: CaM structure showing labeling sites in the N-terminal domain at residues 5 and 44. Right: C-terminal domain labeling sites at residues 78 and 117. The structures were rendered in the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation

T5C-T44C-CaM and D78C-T117C-CaM were expressed as described elsewhere.29 The mutants were labeled with maleimide derivatives of Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) and Atto 740 (Atto-tec GMBH, Siegen, Germany). For labeling, 1 mg of Alexa Fluor 488 maleimide was dissolved in 250 μL of storage buffer and 1 mg of Atto 740 maleimide was dissolved in 250 μL of DMSO. A 2.1 mg vial of CaM was mixed with a 6-fold molar excess of TCEP. A solution of 4 M NaCl in the storage buffer was prepared, and 500 μL was pipetted into the TCEP/CaM solution and stirred for 5 minutes. The two dye solutions were mixed, and the dye mixture was added dropwise to the protein solution and allowed to react in the dark at room temperature for 90 minutes. The unreacted dye was then separated from the labeled protein on a 40 cm by 1 cm Sephadex G25 size exclusion column equilibrated with the storage buffer. Labeled protein was purified by HPLC as described elsewhere.29 The collected fractions were dialyzed from the HPLC solvents into the storage buffer. Mass spectrometry was performed to verify the sample contents.

A polyproline peptide with the sequence Gly-(Pro)15-Cys was purchased from Sigma Genosys (St. Louis, MO). The carboxyl terminal cysteine was labeled with Atto 740 maleimide and the amino terminal glycine was labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 succinimidyl ester (Invitrogen Corp. Carlsbad, CA) as described previously.21

The high Ca2+ buffer consisted of 10 mM HEPES, 0.1 M KCl, 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.1 mM CaCl2. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 with HCl and KOH, and the solution was filtered using a 0.2-μm syringe filter. The low Ca2+ buffer was prepared with 10 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2 and 3 mM EGTA. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 by addition of HCl or KOH, and the solution was filtered through a 0.2 μm syringe filter. The intermediate Ca2+ buffer was prepared by adding high-Ca2+ buffer and a small quantity of 100-mM Ca2+ stock solution to the low-Ca2+ buffer until the desired Ca2+ concentration was reached as determined by a calibrated Ca2+ selective electrode. Free Ca2+ concentrations were estimated to be 100 μM (high Ca2+ buffer), 4 μM (intermediate Ca2+ buffer), and <20 nM (low Ca2+ buffer).

Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy

Two-channel FCS measurements were carried out on an inverted fluorescence microscope system described previously.21 Optical filters (all from Chroma, Rockingham, VT) included the microscope dichroic (500DCXR), FRET dichroic (565DCLP), donor emission filter (HQ535/50M), and the acceptor emission filter (HQ667/LP). Data were collected in time-stamped (“photon”) mode and correlation functions calculated from photon arrival times as described by previous workers.30-33 Correlation functions were corrected for after-pulsing.34 Overlap of focal volumes probed by green and red channels was verified by comparing FCS correlation functions from fluorescein collected in the two channels, where the signal in the red channel arose from cross-talk of fluorescein fluorescence into the red channel (about 15%). Proper overlap was confirmed by the overlap of autocorrelation functions calculated from the two channels. All measurements were carried out at room temperature (20°C).

Data Fitting

Correlation functions were calculated from the signals recorded in the green (G) and red (R) channels, autocorrelation functions for G and R and cross correlations between G and R. The four correlation functions were fit globally to determine dynamic parameters, as described previously.21 Global fitting allows determination of the contributions from intramolecular dynamics through the different functional form of the dynamics contributions to the autocorrelation and cross-correlation functions. Autocorrelation functions were fit to equations of the form

| (1) |

where xx = GG or RR the green (G) or red (R) channels, N is the average number of molecules in the focal volume, GT (τ) is the triplet contribution to the correlation, Gdiff (τ) is the contribution from translational diffusion, and Exx(τ) is the contribution from intramolecular dynamics. The triplet contribution GT (τ) is35:

where f is the amplitude for the triplet component and τT is the triplet time constant. The diffusion component Gdiff(τ) is given by36:

where τd is the average transit time through the focal region and p is the axial-radial ratio, which was determined from FCS of dye solutions and fixed for data fitting.

Cross-correlation functions were fit to a similar correlation decay function but without the triplet decay component:

| (2) |

where xy = GR or RG and Exy(τ) is the contribution to the cross-correlation from intramolecular dynamics. In the absence of intramolecular dynamics (e.g. for polyproline, see below), we take Exx(τ) = Exy(τ) = 1. When intramolecular dynamics are present, the intramolecular dynamics contributions to the auto and cross-correlation functions can be expressed17,21,37,38:

| (3) |

where τ1 is the time constant for the dynamics and the static components b and d represent contributions from FRET states that interchange on a time scale much longer than the transit time τd (see Supplementary Information for ref. 21). For global nonlinear least squares fitting, χ2 was calculated with each point weighted by the inverse of the sample variance σ2, which was calculated by cutting each data file into eight equal sections, computing the correlations for each segment, and determining the variance σ2 for each correlation point.21

Results

Polyproline FCS

We described previously the use of polyproline labeled with a FRET pair as a control system for FRET-FCS.21 The polyproline control has two functions. First, it serves as a negative control to verify that apparent intramolecular dynamics are not detected artifactually for a system where none are expected on the microsecond time scale. Second, fits yield values for the triplet correlation times of AF 488 and Atto 740 so that these parameters can be fixed in fits to CaM data.

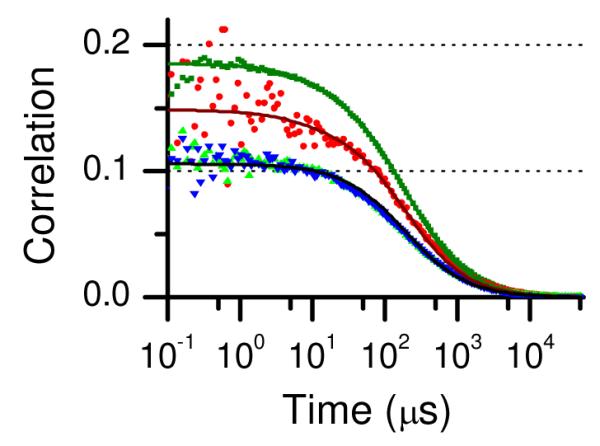

Figure 2 shows the correlations of the data for polyproline and the resulting fit using the multiple static FRET state model.21 Table 1 contains the parameters for the fit shown in Figure 2. Several features are clear from examination of the correlation functions. First, the initial amplitudes of the two autocorrelation functions do not match either each other or the initial amplitudes of the cross-correlation functions. We reported similar findings for polyproline labeled with AF488 and TR and showed that unequal initial amplitudes are a consequence of multiple FRET states or of the presence of molecules with photobleached acceptor fluorophores.21 The existence of multiple FRET states has an effect analogous to having different concentrations of donor and acceptor fluorophores. Second, we note that the GR and RG cross-correlation functions overlap each other as expected for a system with time-inversion symmetry.

Figure 2.

Correlation functions for polyproline-AF488-Atto 740: GGG(τ) (green squares), GRR(τ) (red circles), GGR(τ) (green triangles), and GRG(τ) (blue inverted triangles). The solid lines show a global fit where the transit times for GGG(τ), GGR(τ), and GRG(τ) were linked (see text) and the initial amplitudes were allowed to vary independently. Fitting parameters are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Fitting parameters for polyproline-AF 488-Atto 740.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| fT1 a | 0.07 |

| τT1 (μs) a | 10 |

| fT2 a | 0.06 |

| τT2(μs) a | 6.7 |

| Ntot | 7.81 |

| τd(μs) | 188 |

| E1 b | 0.89 |

| f1 | 0.36 |

| E2 | 0.27 |

| f2 | 0.64 |

Triplet parameters: fT1: fraction for donor fluorophore; τT1: triplet correlation time for donor fluorophore; . fT2: fraction for acceptor fluorophore; τT2: triplet correlation time for acceptor fluorophore.

Parameters E1, f1, and E2, are the FRET efficiency of FRET state 1, fractional population of FRET state 1, and FRET efficiency of FRET state 2, respectively. See eqs 8-10 in ref. 21.

Third, the time dependence of the correlation decays was fit without intramolecular dynamics. After accounting for decay of the triplet contributions to the autocorrelations, the time dependence is the same for each of the autocorrelation and cross-correlation curves and can be fit without a contribution from intramolecular dynamics. (We note one exception to this statement: Although the correlation functions GGG(τ), GGR(τ) and GRG(τ) were fit well with the same transit time τd, we found it useful to fit the RR autocorrelation GRR(τ) with a slightly shorter transit time to account in an ad hoc way for photobleaching of Atto 740, which results in a slightly faster decay of the red autocorrelation function, as observed previously.21) To illustrate their overlapping time dependence, the four correlations for polyproline are plotted in Figure S1 in the Supporting Information normalized to have the same amplitude at τ = 50 μs, long enough so that the triplet contributions are no longer present. The close overlap of the correlation functions confirms the absence of detectable FRET dynamics in polyproline on this time scale. The fact that good overlap is also evident for τ < 10 μs shows that contributions from triplet dynamics are small.

CaM FCS

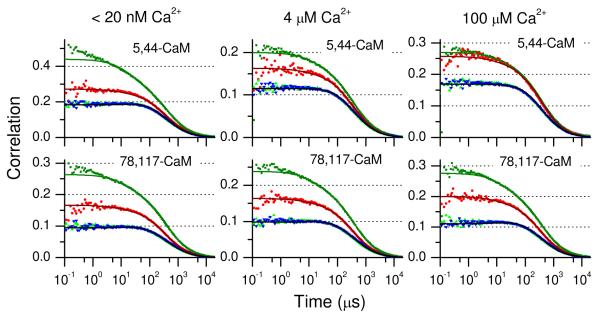

CaM constructs with Cys substitutions at sites 5-44 and 78-117 were selected for measurements of intra-lobe motion of the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of CaM with and without bound Ca2+. The resulting correlation functions are shown in Figure 3 for CaM in low, intermediate, and high Ca2+ buffers. As with polyproline, the initial amplitudes of the two autocorrelation functions do not overlap each other, indicating multiple FRET states in the sample.21 The cross correlation curves GGR(τ) and GRG(τ) overlay each other well as expected. However, in contrast to the results for polyproline, the time dependences of the autocorrelation and cross-correlation functions are not the same. This is illustrated in Figure S2 in the Supporting Information, where the correlation functions are scaled to the same value at 50 μs. The two autocorrelation functions GGG(τ) and GRR(τ) decay more rapidly over the first ~100 μs than the corresponding cross-correlation functions GGR(τ) and GRG(τ). This is a clear signature of intramolecular dynamics, which contribute a decay component to the autocorrelations and a rising component to the cross correlation functions (eq 3). In some cases, such as 5,44-CaM at low Ca2+, it is possible to discern a slight rise in the cross correlations over the first 10 to 20 μs. The time dependence of the cross correlations deviates from that of the autocorrelations on the ~100-μs time scale as well. Consequently, in contrast to the correlations for polyproline, for CaM it was necessary to account for contributions from intramolecular dynamics in the fits.

Figure 3.

Correlation functions for CaM-AF488-Atto 740: GGG(τ) (green squares), GRR(τ) (red circles), GGR(τ) (green triangles), and GRG(τ) (blue inverted triangles). The solid lines show global fits where the transit times for GGG(τ), GGR(τ), and GRG(τ) were linked, and the initial amplitudes were allowed to vary independently. Fitting parameters are in Table 2. The top panels show the correlations for 5,44-CaM and the lower panels show the correlations for 78-117-CaM. Left: apoCaM (Ca2+ concentration <20 nM); Center: Ca2+ concentration 4 μM; Right: holoCaM (Ca2+ concentration 100 μM).

For each sample at each Ca2+ concentration, the four correlation functions (GG, RR, GR, and RG) were fit globally to eqs 1-3 in order to determine time constants and amplitudes for intramolecular dynamics. Table 2 shows the parameter values from the fits for 5-44-CaM and 78-117-CaM correlations at three Ca2+ concentrations (<20 nM, 4 μM, and 100 μM). Triplet correlation times and amplitudes were fixed to values determined for the polyproline Alexa Fluor 488-Atto 740 correlation fits (Table 1). The correlation fits reveal intramolecular dynamics on the time range of 30 to 40 μs (τ1 in Table 2).

Table 2.

Fitting parameters for CaM-AF488-Atto 740.a

| Parameter | 5,44-CaM | 78,117-CaM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| low Ca2+ | 4 μM Ca2+ |

100 μM Ca2+ |

low Ca2+ | 4 μM Ca2+ |

100 μM Ca2+ |

|

| Ntot | 4.16 | 7.10 | 4.78 | 7.17 | 7.26 | 6.14 |

| τd(μs)b | 405 | 381 | 395 | 406 | 382 | 371 |

| τd-RR (μs)c | 389 | 368 | 376 | 366 | 353 | 340 |

| τ 1 | 32 | 39 | 41 | 27 | 29 | 27 |

| a | 0.36 | 0.12 | 0.062 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.19 |

| c | 0.042 | 0.040 | 0.055 | 0.039 | 0.040 | 0.059 |

| b | 0.35 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.39 |

| d | 0.041 | 0.064 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.095 | 0.12 |

Triplet parameters were fixed to values determined for the same dye pair attached to polyproline (see Table 1). Parameters for intramolecular dynamics are defined in eq 3.

Transit time for GGG(τ), GGR(τ), and GRG(τ).

The transit time for GRR(τ) was allowed to vary independently to account for photobleaching of the acceptor during transit through the probe volume.

Based on these results, we can conclude that intra-domain fluctuations are present in both domains. The time constants are similar for both domains with no clear dependence on Ca2+ concentration. The amplitude of the dynamics, however, are different for the N-terminal and C-terminal domains. The amplitudes are best described by the fits to the green-green (GG) correlation due to the presence of less measurement noise in the stronger AF-488 emission signal compared to the emission from Atto 740. For the N-terminal domain (5-44-CaM) the amplitude a depends markedly on Ca2+, decreasing from 0.36 at low Ca2+ to 0.062 at high Ca2+. For the C-terminal domain (78-117-CaM), on the other hand, the amplitude a shows no significant variation with Ca2+ and has a value intermediate between that of the N-terminal domain at low Ca2+ and at high Ca2+.

Adequate fits to the CaM correlation decays also required a static component representing states that interchange on a time scale longer than the transit time τd. It was therefore not possible to determine the corresponding time constant from FCS data, but the corresponding amplitudes (b and d) were varied as fitting parameters and are listed in Table 2. A similar contribution was found previously for 34,110-CaM with FRET labels on opposite lobes of CaM.21 The amplitude of the static FRET component was higher for 78-117-CaM than for 5-44-CaM. For both domains, the static FRET amplitude decreased as the Ca2+ concentration was increased.

It is also apparent that the GGG(τ) autocorrelations for 5,44-CaM and 78-117-CaM at low Ca2+ (and, to a lesser extent, 78-117-CaM at 4 μM Ca2+) contain a decay component of < 2-4 μs that is not accounted for by the fits. This component may arise from triplet dynamics of AF-488. However, nearly the same excitation power (25 μW) was used for these measurements as for the polyproline measurements (20 μW) where the component is absent, suggesting that triplet dynamics cannot account for this component, since one would expect the amplitudes and time constants for triplet dynamics to be similar at similar excitation intensities. Specific Ca2+-dependent interactions with the fluorophore also seem unlikely given the high ionic strength of the buffers. Thus, the fast component may report fast fluctuations within the domains at low Ca2+ concentrations.

Discussion

As demonstrated in a number of previous papers, intramolecular dynamics on the microsecond to millisecond time scale can be detected with high sensitivity by dual-color FCS coupled with FRET.16-20 Recently we presented FCS-FRET data for CaM with one dye attached to the N-terminal domain of CaM and the other to the C-terminal domain to characterize inter-domain dynamics.21 The results revealed intramolecular dynamics on the 100-μs time scale for Ca2+-loaded CaM, but not for apoCaM. In the present paper we demonstrate application of this approach to intra-domain dynamics in CaM.

Intra-domain dynamics from FCS

For sensitivity to intradomain dynamics, the fluorophores were attached either both in the N-terminal or both in the C-terminal domain. Intra-domain dynamics were identified on the time scale of ~30 - 40 μs for both 5,44-CaM and 78-117-CaM (Figure 3 and Table 2). The time scales of the dynamics are approximately the same for all Ca2+ concentrations measured and for labels on either the N-terminal or C-terminal domains. That these contributions arise from FRET fluctuations is verified by the different time dependences of the autocorrelations GGG(τ) and GRR(τ) compared to the cross correlations GGR(τ) and GRG(τ). Control measurements on polyproline (Figure 1 and Table 1) show no such contributions, helping to verify that these results are not artifactual.

Although the time constants were essentially the same for all measurements, the amplitudes of the dynamics depend on domain and Ca2+. For the N-terminal domain the dynamics present at low Ca2+ are nearly abolished at high Ca2+, suggesting that the dynamics detected are coupled to motions involved in Ca2+ binding such as opening and closing of the EF-hand Ca2+ binding domains. For the C-terminal domain the dynamics remain essentially constant in amplitude at all three Ca2+ concentrations. Thus the dynamics detected in the C-terminal domain are not coupled to Ca2+ occupancy. The difference between the responses of dynamics in the N-terminal and C-terminal domains to Ca2+ illustrates the different dynamic properties of the two domains. A second component reveals the presence of FRET states that are static on the time scale of the correlation decays and thus interchange on a longer time scale. The amplitudes (b and d) are moderately sensitive to Ca2+, decreasing with increasing Ca2+ concentration for both N-terminally and C-terminally labeled CaM.

Structural and kinetic studies of CaM

Structural studies have shown that the conformations within both the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of CaM change upon Ca2+ binding.39-44 In the solution structures of apoCaM, the EF hands are in a “closed” conformation.41,42 Ca2+ binds in the EF hands to lock in an “open” conformation.45 The solution structure of holoCaM reveals an open Ca2+-bound conformation for the C-terminal domain Ca2+ binding sites but a less open conformation in the N-terminal domain.43 EF-hand conformations are coupled to more global conformational changes within domains.40,43,44 As a result, Ca2+ binding triggers global conformational changes. Differences in solution and x-ray structures of CaM reinforce the notion of flexibility within the N-terminal and C-terminal domains.

Conformational flexibility within both the N-terminal and C-terminal domains is thus required for CaM to bind Ca2+. Indeed, conformational exchange was detected by NMR studies in the C-terminal domain of apoCaM on timescales of 350 μs,46 and (in the presence of Ca2+) in a C-terminal fragment E140Q mutant (which eliminates Ca2+ binding at EF hand 4) with an exchange time of ~25 μs.47,48 Exchange dynamics in the C-terminal domain appear to involve transient unfolding of secondary structural elements.49 In the solution structures of apoCaM40,42 large rms deviations were found in the N-terminal tail (including the labeling site at residue 5), in the loop between helices B and C (including residue 44), in the loop between helices D and E (including residue 78) and between helices F and G (including residue 117). Hence, the N-terminal and C-terminal labeling sites are expected to fluctuate. A dynamical simulation of the N-terminal lobe bears this out, showing transitions between holo-like and apo-like conformations.50 The two domains also differ in thermodynamic stability. The C-terminal domain of apoCaM unfolds at a lower temperature than the N-terminal domain and has been reported to be partially unfolded at room temperature.51-55

The above studies show that the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of CaM are dynamic, particularly in apoCaM. One measure of the dynamics in CaM can be found in Ca2+ on and off-rates, which are different for the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of CaM. Stop-flow fluorescence experiments found Ca2+ off rates of 200 - 700 s−1 (depending on buffer conditions) for the N-terminal domain of CaM and 7 - 24 s−1 for the C-terminal domain.24,25,56 Ca2+ binding rate constants were also higher for the N-terminal domain (1.6 × 108 M−1 s−1) than the C-terminal domain (2.3 × 106 M−1 s−1). A study of Ca2+ binding to CaM in a microfluidic mixer showed two kinetic components,57 one with a rate constant of ~6×107 M−1 s−1 and a second component with a limiting rate of 50 s−1 at high Ca2+ concentrations, suggesting that Ca2+ binding at high Ca2+ concentrations is rate-limited by a conformational change.

Differences have also been reported in the flexibility of each domain. MD studies of CaM predicted greater flexibility in the N-terminal compared to the C-terminal domain.26-28,58 In a recent theoretical study Tripathi and Portman found that local unfolding (“cracking”) is necessary in the closed-to-open transition in the C-domain, in contrast to the more flexible N-domain.28 The results presented here are consistent with the higher flexibility of the N-domain in apoCaM.

Given the conformational changes necessary for Ca2+ binding, the rates of Ca2+ dissociation or binding must represent lower limits on the rates of conformational changes. According to the population shift picture of protein function,2-7 the conformational changes required for Ca2+ binding are already present within the dynamics of CaM in the absence of Ca2+. From this point of view, static closed or open structures of CaM are not expected, and fluctuations exploring a range of conformations can be anticipated within each domain in the absence of Ca2+. Interestingly, the dynamics observed are significantly faster than Ca2+ binding and dissociation kinetics, suggesting either that the dynamics are decoupled from Ca2+ binding and release, or that Ca2+ binding and dissociation events occur at low probability with each conformational fluctuation.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates detection of dynamics by FRET-FCS with FRET probe labeling sites separated by 25 to 30 Å. The goal of the study was to investigate conformational dynamics within the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of CaM. The use of an acceptor fluorophore absorbing in the near-infrared produced a Förster radius of <40 Å, providing sensitivity to FRET over shorter distances than typical for commonly used visible fluorophores. The presence and time scale of intramolecular dynamics were detected by application of a global fitting approach reported previously.21

Comparison of autocorrelation and cross-correlation decays reveals dynamics in both the N-terminal and C-terminal domains on the 30 to 40 μs time scale. The results indicate a greater amplitude of dynamics at low Ca2+ in the N-terminal domain of CaM, consistent with the reported greater flexibility of that domain. The amplitude of dynamics was strongly sensitive to Ca2+ in the N-terminal domain, in contrast to the C-terminal domain, where the amplitude changed little with Ca2+ concentration. The Ca2+ dependence of amplitudes suggests that the dynamics detected in the N-terminal domain (but not in the C-terminal domain) are coupled to conformational changes in the Ca2+-binding E-F hand domains. This result is consistent with the presence of dynamic, flexible domains.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (CHE-0710515) and the American Heart Association (AHA 0755711Z). E.S.P. acknowledges support from the Pharmaceutical Aspects of Biotechnology NIH Training Grant (NIGMS 08359).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Figures showing autocorrelation and cross-correlation functions for polyproline, 5-44-CaM and 78-117-CaM scaled to GGG(τ) at τ = 50 μs. Figure S1 shows nearly complete overlap of autocorrelation and cross-correlation functions for polyproline. Figure S2 shows non-overlapping time dependence of autocorrelation and cross-correlation functions for 5-44-CaM and 78-117-CaM.

References

- (1).Frauenfelder H, Sligar SG, Wolynes PG. Science. 1991;254:1598. doi: 10.1126/science.1749933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).James LC, Tawfik DS. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:361. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00135-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hammes GG. Biochemistry. 2002;41:8221. doi: 10.1021/bi0260839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Henzler-Wildman K, Kern D. Nature. 2007;450:964. doi: 10.1038/nature06522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Weber G. Biochemistry. 1972;11:864. doi: 10.1021/bi00755a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Gunasekaran K, Ma B, Nussinov R. Proteins. 2004;57:433. doi: 10.1002/prot.20232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Gsponer J, Christodoulou J, Cavalli A, Bui JM, Richter B, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M. Structure. 2008;16:736. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Elson E, Magde D. Biopolymers. 1974;13:1. doi: 10.1002/bip.1974.360130103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Magde D, Elson EL, Webb WW. Biopolymers. 1974;13:29. doi: 10.1002/bip.1974.360130103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Rigler R, Mets U, Widengren J, Kask P. Eur. Biophys. J. 1993;22:169. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Chattopadhyay K, Saffarian S, Elson EL, Frieden C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:14171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172524899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Yang H, Luo G, Karnchanaphanurach P, Louie T-M, Rech I, Cova S, Xun L, Xie XS. Science. 2003;302:262. doi: 10.1126/science.1086911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Jung J, Van Orden A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:3648. doi: 10.1021/jp0453515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Rogers JMG, Polishchuk AL, Guo L, Wang J, DeGrado WF, Gai F. Langmuir. 2011;27:3815. doi: 10.1021/la200480d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Selvin PR. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:730. doi: 10.1038/78948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Hom EFY, Verkman AS. Biophys. J. 2002;83:533. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75189-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Eid JS. Ph.D. Dissertation. Urbana, Illinois: 2002. Two-photon Dual Channel Fluctuation Correlation Spectroscopy: Theory and Application. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Margittai M, Widengren J, Schweinberger E, Schroder GF, Felekyan S, Haustein E, Konig M, Fasshauer D, Grubmuller H, Jahn R, Seidel CA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:15516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2331232100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Slaughter BD, Allen MW, Unruh JR, Urbauer RJB, Johnson CK. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:10388. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Gurunathan K, Levitus M. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;114:980. doi: 10.1021/jp907390n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Price ES, DeVore MS, Johnson CK. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:5895. doi: 10.1021/jp912125z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Linse S, Helmersson A, Forsén S. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:8050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Pedigo S, Shea MA. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10676. doi: 10.1021/bi00033a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Martin SR, Andersson Teleman A., Bayley PM, Drakenberg T, Forsén S. Eur. J. Biochem. 1985;151:543. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb09137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Brown SE, Martin SR, Bayley PM. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:3389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Barton NP, Verma CS, Caves LSD. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2002;106:11036. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Barton NP, Verma CS, Caves LSD. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2003;107:2170. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Tripathi S, Portman JJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:2104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806872106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Allen MW, Urbauer RJB, Zaidi A, Williams TD, Urbauer JL, Johnson CK. Anal. Biochem. 2004;325:273. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Eid JS, Muller JD, Gratton E. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2000;71:361. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Magatti D, Ferri F. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2003;74:1135. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Wahl M, Gregor I, Patting M, Enderlein J. Opt. Express. 2003;11:3583. doi: 10.1364/oe.11.003583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Felekyan S, Kuehnemuth R, Kudryavtsev V, Sandhagen C, Becker W, Seidel CAM. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2005;76 083104/1. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Zhao M, Jin L, Chen B, Ding Y, Ma H, Chen D. Appl. Opt. 2003;42:4031. doi: 10.1364/ao.42.004031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Widengren J, Mets U, Rigler R. J. Phys. Chem. 1995;99:13368. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Rigler R, Elson ES. Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy: Theory and Applications. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Berne BJ, Pecora R. Dynamic Light Scattering. Wiley; New York: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Torres T, Levitus M. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:7392. doi: 10.1021/jp070659s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Babu YS, Bugg CE, Cook WJ. J. Mol. Biol. 1988;204:191. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90608-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Finn BE, Evenas J, Drakenberg T, Waltho JP, Thulin E, Forsén S. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1995;2:777. doi: 10.1038/nsb0995-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Kuboniwa H, Tjandra N, Grzesiek S, Ren H, Klee CB, Bax A. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1995;2:768. doi: 10.1038/nsb0995-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Zhang M, Tanaka T, Ikura M. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1995;2:758. doi: 10.1038/nsb0995-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Chou JJ, Li S, Klee CB, Bax A. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:990. doi: 10.1038/nsb1101-990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Nelson MR, Chazin WJ. Protein Sci. 1998;7:270. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Herzberg O, Moult J, James MN. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:2638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Tjandra N, Kuboniwa H, Ren H, Bax A. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995;230:1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Evenäs J, Malmendal A, Akke M. Structure. 2001;9:185. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00575-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Lundström P, Akke M. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:1685. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Lundström P, Mulder FA, Akke M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:16984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504361102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Zuckerman DM. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:5127. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Tsalkova TN, Privalov PL. J. Mol. Biol. 1985;181:533. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Martin SR, Bayley PM. Biochem. J. 1986;238:485. doi: 10.1042/bj2380485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Masino L, Martin SR, Bayley PM. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1519. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.8.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Rabl C-R, Martin SR, Neumann E, Bayley PM. Biophys. Chem. 2002;101-102:553. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Biekofsky RR, Martin SR, McCormick JE, Masino L, Fefeu S, Bayley PM, Feeney J. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6850. doi: 10.1021/bi012187s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Johnson JD, Snyder C, Walsh M, Flynn M. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Park HY, Kim SA, Korlach J, Rhoades E, Kwok LW, Zipfel WR, Waxham MN, Webb WW, Pollack L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710810105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Tripathi S, Portman JJ. J Chem Phys. 2008;128:205104. doi: 10.1063/1.2928634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.