Abstract

Background

Cholangiocarcinoma originates from bile duct epithelial cells in the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary system. We recently observed that triptolide (a diterpenoid triepoxide) is effective in inducing apoptosis in pancreatic tumors. Death Receptors 4 and 5 are overexpressed in several cancer types, and their activation by TRAIL induces cell death. The principal objective of this study was to determine the effects of combination therapy with TRAIL and triptolide in cholangiocarcinoma.

Materials and Methods

Two cholangiocarcinoma cell lines were incubated with various doses of triptolide and TRAIL, alone and in combination; cell viability was assessed at 24 and 48 hours. Annexin staining and caspase-3 activity were measured after 24 hours of triptolide, TRAIL or combination treatment. Western blots assessed protein levels of PARP and XIAP.

Results

Combination treatment using TRAIL and triptolide decreased cell viability in all cell lines at 48 hours, with greater cell killing than that which was observed with either drug alone. This decrease in viability was associated with increases in Annexin staining and caspase-3 activity. Western blot analysis demonstrated increases in PARP cleavage and decreases in XIAP expression that were dose-dependent.

Conclusions

TRAIL and triptolide in combination decreased cell viability and enhanced apoptosis. Furthermore, Western blot analysis suggests that triptolide sensitizes cells to TRAIL-induced apoptotic cell death by inhibiting expression of XIAP, a protein known to inhibit apoptosis. Our results demonstrate that combination of TRAIL and triptolide enhance apoptosis in cholangiocarcinoma cell lines.

Keywords: Cholangiocarcinoma, triptolide, TRAIL, apoptosis, XIAP and PARP

INTRODUCTION

Cholangiocarcinoma is the second most common primary malignancy of the liver, originating from bile duct epithelial cells in the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary system.1 The incidence of cholangiocarcinoma is increasing in the United States, with the age-adjusted mortality increasing nearly 10-fold in the last 30 years.2 Cholangiocarcinoma’s high mortality rate is felt to be consequent to diagnosis late in the disease process, as patients may bear the burden of disease in the absence of symptoms for a considerable period. At this time, surgical resection is the only effective curative treatment. Even after operative intervention, patients with cholangiocarcinoma have high rates of local and distant recurrence, with overall 5-year survival ranging from 10–50%.1 This is minimally improved in the cohort of patients with negative histological margins post-resection (27–62%).1 The current systemic chemotherapy agents gemcitabine, docetaxel and 5-fluorouracil have failed to improve survival, either when used individually or as regimens; therefore, additional chemotheraputic medications are vital to decreasing mortality.

Triptolide, a diterpenoid triepoxide, is purified from the Chinese herb Tripterygiumw wilfordii. Previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that triptolide decreases cellular viability in vitro and tumor size in vivo in several pancreatic cancer and neuroblastoma cell lines through apoptotic cell death.3–5 Apoptosis is comprised of numerous regulatory steps, and precedes via either the intrinsic or extrinsic pathways. This programmed cell death is useful for elimination of redundant, damaged or infected cells. Malignant cells, however, have found mechanisms to avoid programmed cell death, and, for this reason, induction of apoptosis is an attractive pharmacologic target for neoplastic disease.

Apo 2 ligand/TRAIL was discovered in 1995 and is a member of the Tumor-Necrosis Factor Receptor (TNF) Family.6 It is less toxic with systemic administration than other members of the TNF family and has 5 different receptors. Among these, apoptosis is activated though the extrinsic pathway by Death Receptors 4 (DR4) and 5 (DR5).7 The recombinant soluble Apo2L/TRAIL has been shown in the literature to induce apoptosis in human cancer cell lines of the pancreas, colon, kidney, and breast.7–10

Studies from our laboratory have recently demonstrated that triptolide and TRAIL combination treatment synergistically induce apoptosis in several human pancreatic cancer cell lines.5 We, therefore, hypothesized that the combination of triptolide and TRAIL would enhance apoptosis in human cholangiocarcinoma cells, as well.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

KMCH cholangiocarcinoma cells were obtained from Dr. G. Gores (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM). The cholangiocarcinoma cell line SkChA-1 was provided by Dr. LaRusso (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN); cells were grown in RPMI medium. All media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin during growth conditions. All cells were maintained at 37ºC in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

In vitro treatment with triptolide and TRAIL

Triptolide (Calbiochem, EMD Chemicals, Inc., Gibbstown, NJ) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. TRAIL (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California) was dissolved in 5% albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at a concentration of 1mg/ml. For cell viability assays and caspase-3 quantification, all cell lines were seeded in serum-containing media onto 96-well plates at a density of 3 X 103 cells per well. For Annexin-V staining, cells were plated in serum-containing media onto 6-well plates at a density of 125 X 103 cells per well. For extraction of protein, cells were seeded in serum-containing media onto 10-cm tissue culture dishes at a density of 8 X 105 cells per dish. After 24 hours of incubation, cells were then treated with varying concentrations of triptolide alone, TRAIL alone, or a combination of triptolide and TRAIL for 24 to 48 hours in serum-free media at 37ºC. Co ntrols were treated under the same serum-free conditions.

Determination of cell viability

Cellular viability was assessed using the Dojindo Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD). After cells were incubated in 96-well plates for 24 hours and exposed to various concentrations of triptolide, TRAIL, or combination treatment for 24 and 48 hours, 10 μL of tetrazolium substrate was added onto each well of the plate. Plates were incubated at 37ºC for 3 hours and absorbance was measured at 450 nm. These experiments were done in triplicate and repeated three times.

Caspase-3 activity quantification

Caspase-3 activity was measured using the Caspse-Glo 3/7 Assay (Promega, Madision, WI) as directed by the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were seeded in opaque 96-well plates, incubated for 24 hours, and treated with various concentrations of triptolide alone, TRAIL alone or combination treatment for 24 hours. After 24 hours, 100 μL of Caspase-Glo 3/7 reagent was added to each well and caspase-3 activity was measured using a luminometer as previously described.5 These experiments were done in duplicate and repeated three times.

Annexin-V staining

Phosphatidylserine externalization was determined using Guava Nexin Reagent and the Guava personal cell analysis flow cytometer (Guava Technologies, Hayward, CA). Cells were seeded in 6-well plates and treated with drug for 24 hours. The manufacturer’s protocol was then used to prepare and stain the suspended cells with 100 μL of the Guava Nexin reagent. Samples were analyzed using flow cytometry as previously described.3 These experiments were repeated three times.

Immunoblot analysis of XIAP and PARP

Following the seeding of cells onto 10-cm tissue culture plates and the treatment with various concentrations of triptolide, TRAIL, or combination treatment for 24 hours, cell lysates were prepared as previously described.5 Western blotting was done using antibodies for X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) (rabbit-monoclonal XIAP antibody from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (rabbit-polyclonal PARP antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Actin (goat-polyclonal actin antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology) expression was used as an internal control.

Statistical analysis

All experiments have been performed three times and data is expressed as mean values ± standard error of mean. The Student’s t test was calculated to determine the significance between the treatment conditions and the controls where a value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Treatment with triptolide or TRAIL decreases cell viability in cholangiocarcinoma cells

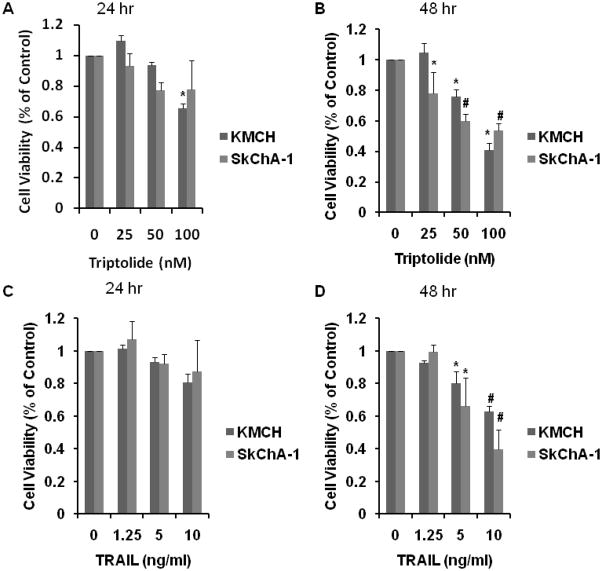

Two cholangiocarcinoma cell lines were treated with increasing concentrations of triptolide (0–100 nM) or TRAIL (0–10 ng/ml) for 24 and 48 hours. Figures 1A and 1B show a significant decrease in cell viability after 24 and 48 hours of triptolide treatment in all cell lines, with KMCH showing greater sensitivity to triptolide than SkChA-1. All cell lines show a significant decrease in cell viability with TRAIL therapy.

Figure 1.

Cell viability. KMCH and SkChA-1 were treated with triptolide at concentrations ranging from 25 to 100 nM for 24 (A) and 48 hours (B). Cells were also treated with TRAIL at concentrations ranging from 1.25 to 10 ng/ml for 24 (C) and 48 hours (D). All cell lines treated with triptolide had decreased cell viability with increased triptolide concentration and time. All cell lines demonstrated a dose and time dependent decease in cell viability with TRAIL treatment. Data is expressed as mean± SEM of three independent experiments with duplicates. * P < 0.05 and # P < 0.001 as compared to controls.

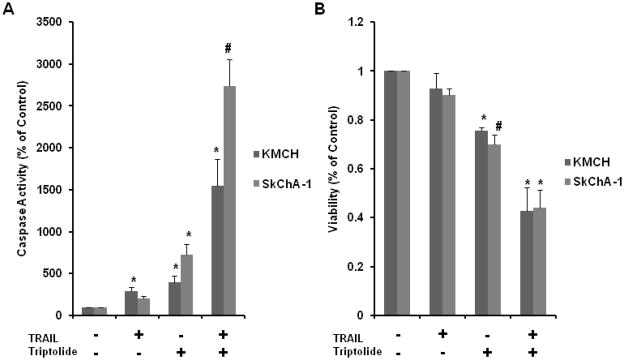

Combination treatment with TRAIL and triptolide enhances caspase-3 activity

We have previously shown that triptolide alone, as well as in combination with TRAIL, increases activity of caspase-3, the central executioner of the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways in multiple malignancies.3–5,11 In order to elucidate whether this finding is true of cholangiocarcinoma, our cell lines were treated for 24 hours with TRAIL 1.25 ng/ml, triptolide 50 nM or the combination of TRAIL and triptolide for 24 hours. Figure 2A demonstrates a significant increase in caspase-3 activity with the combined TRAIL and triptolide treatment, more so than that which is observed when either drug is used alone. These increases in caspase-3 activity correlated with decreases in cell viability at 48 hours (Figure 2B) for all cell lines.

Figure 2.

Caspase-3 and cell viability. KMCH and SkCHA-1 were treated with TRAIL 1.25ng/ml alone, triptolide 50 nM alone or the combination of TRAIL and triptolide. Caspase-3 activity was measured at 24 hours(A); cell viability was measured at 48 hours (B). The combination of TRAIL and triptolide resulted in a significant increase in caspase-3 activity that was more than when either compound was used alone, which corresponded with a decrease in cell viability. Data is expressed as mean± SEM of three independent experiments with duplicates. * P < 0.05 and # P < 0.001 as compared to controls.

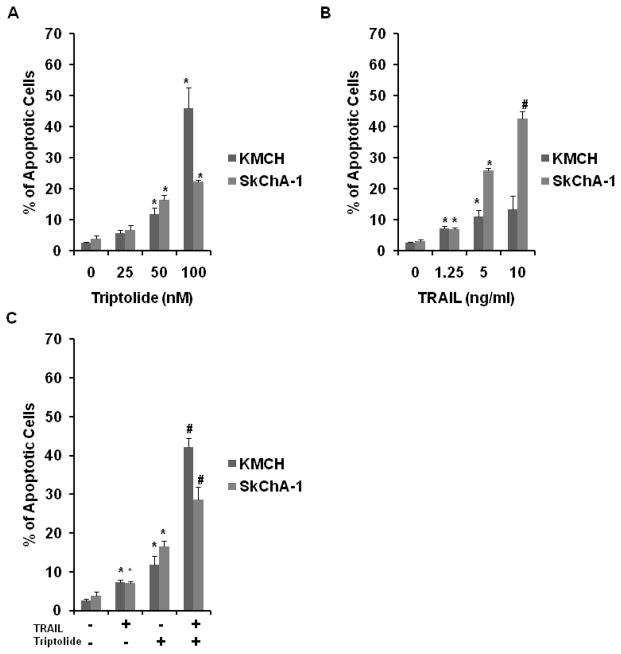

Annexin-V staining is increased with combination triptolide and TRAIL treatment

To further support our hypothesis that cholangiocarcinoma cellular viability decreased with triptolide and TRAIL via apoptosis, we measured phosphatidylserine externalization after cells were incubated for 24 hours with increasing concentrations of triptolide (0–100 nM), TRAIL (0–10 ng/ml) or TRAIL and triptolide (1.25 ng/ml and 50 nM). Lower doses of TRAIL were not explored since the 1.25 ng/ml concentration demonstrated a minimal decrease in cell viability and only a small increase in caspase-3 activity in KMCH and SkChA-1. Both cell lines showed a significant increase in Annexin-V staining in a dose-dependent manner when treated with triptolide (Figure 3A) and TRAIL (Figure 3B). For both cell lines, low doses of TRAIL and triptolide used in combination (Figure 3C) resulted in a percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis that was significantly greater than that which was seen even with the highest concentrations of single-drug treatments. Triptolide concentrations greater than 50 nM were not examined due to our desire to keep combination treatment dosing as low as possible to reduce toxicity. Although combination treatment using TRAIL 1.25 ng/ml and triptolide 25 nM resulted in a significant increase in apoptosis that was greater than monotherapy, this combination dose did not result in the additive effects seen with the higher concentration of triptolide.

Figure 3.

Annexin V. KMCH and SkChA-1 were treated with triptolide at concentrations ranging from 25 to 100 nM (A), TRAIL at concentrations ranging from 1.25 to 10 ng/ml (B) or a combination of TRAIL 1.25 ng/ml and triptolide 50 nM (C) for 24. The low dose combination of TRAIL and triptolide resulted in a significant increase in apoptosis that was comparable to annexin V staining levels at the highest doses of either compound. Data is expressed as mean± SEM of three independent experiments with triplicates. * P < 0.05 and # P < 0.001 as compared to controls.

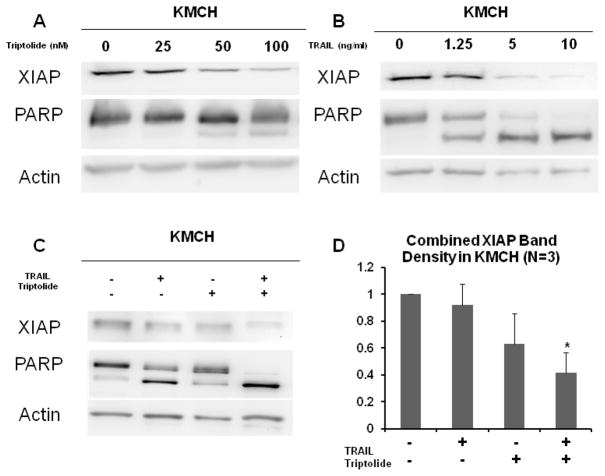

Combination treatment with TRAIL and triptolide decreases XIAP and increases PARP Cleavage

Previous studies have explored the mechanism of TRAIL and triptolide in cancer cells, showing that combination treatment results in decreased levels of XIAP and increased PARP cleavage.12–14 XIAP inhibits apoptosis by binding to caspases-3, -7 and, -9. PARP is cleaved by caspase-3 and is a late marker of apoptosis. In order to elucidate this relationship in cholangiocarcinoma, cells were treated with either increasing concentrations of TRAIL (0–10 ng/ml), triptolide (0–100 nM), or the combination of TRAIL (1.25 ng/ml) and triptolide (50 nM) for 24 hours. Cells were harvested and the expressions of XIAP, PARP, and actin were analyzed by Western blot. All cell lines showed decreasing levels of XIAP and increasing PARP cleavage in a dose-dependent manner when treated with triptolide (Figure 4A). XIAP levels also decreased in all cell lines in a dose-dependent fashion when treated with TRAIL (Figure 4B). All cell lines showed that XIAP decreased maximally and PARP cleavage was greatly increased after treatment with TRAIL and triptolide in combination (Figure 4C). Cumulative data for XIAP band densitometry when TRAIL and triptolide are used independently and in combination show that XIAP is significantly decreased with the combination treatment (Figure 4D). Although Figure 4 only displays results for KMCH, SkChA-1 had similar protein and densitometry patterns.

Figure 4.

Western blot. XIAP and PARP protein levels after 24 hour treatment with triptolide (A), TRAIL (B) or the combination of TRAIL 1.25ng/ml and triptolide 50 nM (C). Densitometry for XIAP showed a maximum decrease when TRAIL 1.25 ng/ml and triptolide 50 nM were combined (D). All cell lines showed decreased XIAP levels with increasing concentration of triptolide. All cell lines showed maximum decrease in XIAP and increased PARP cleavage with combination treatment. Actin protein levels were measured to serve as an internal control. Data is expressed as mean± SEM of three independent experiments with triplicates. * P < 0.05 and # P < 0.001 as compared to controls.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that combination treatment with TRAIL and triptolide decreases cellular viability and enhances cholangiocarcinoma cell death via apoptosis as demonstrated by increased caspase-3 activity and externalization of phosphatidylserine. Previous studies from our laboratory and other authors corroborate the effectiveness of this combination therapy in pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).5,12–14

PARP metabolism is essential for post-translational modification of proteins in eukaryotic cells and inactivation of PARP causes deregulation of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) repair and cell death. PARP activation creates two cleavage products that are markers of apoptosis. Caspase-3 primarily activates PARP; however, studies have additionally indicated that caspase-6 and caspase-7 are also able to cause PARP cleavage.15 We have previously shown by Western blot analysis that maximum PARP cleavage occurs when TRAIL and triptolide are used in combination treatment; this finding is supported by our current data in all cholangiocarcinoma cell lines.5

XIAP is a known inhibitor of caspase-3, caspase-7 and caspase-9.16 Carter et al observed that TRAIL and triptolide combination treatment in AML occurred by the inhibition of XIAP and stimulation of DR5 via p53 activation.14 In this study, all cell lines showed a decrease in XIAP with increasing concentrations of triptolide. Most lines showed a maximum decrease in XIAP when treated with combination therapy. We believe that XIAP’s ability to inhibit caspase activity is the cause of decreased apoptosis despite increased PARP cleavage.

The mechanism responsible for the efficacy of TRAIL and triptolide combination therapy in several in vitro and in vivo cancer studies is controversial. Our findings indicate that combination treatment causes a significant increase in caspase-3 activity, correlating with increased PARP cleavage and decreased XIAP. Triptolide and TRAIL were each independently able to decrease XIAP and increase PARP cleavage in dose-dependent manners in all cell lines. Therefore, we believe that triptolide sensitizes cholangiocarcinoma cells to TRAIL via apoptosis by decreasing XIAP and enhancing caspase-3 activity. This combination therapy with triptolide and TRAIL has important therapeutic potential in clinical translation for cholangiocarcinoma, and further studies are clearly warranted.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grant R01 CA124723 (AKS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aljiffry M, Walsh MJ, Molinari M. Advances in diagnosis, treatment and palliation of cholangiocarcinoma: 1990–2009. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:34. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4240. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33:6. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips PA, Dudeja V, McCarroll JA, Borja-Cacho D, Dawra RK, Grizzle WE, Vickers SM, Saluja AK. Triptolide induces pancreatic cancer cell death via inhibition of heat shock protein 70. Cancer Res. 2007;67:19. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonoff MB, Chugh R, Borja-Cacho D, Dudeja V, Clawson KA, Skube SJ, Sorenson BS, Saltzman DA, Vickers SM, Saluja AK. Triptolide therapy for neuroblastoma decreases cell viability in vitro and inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Surgery. 2009;146:2. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borja-Cacho D, Yokoyama Y, Chugh RK, Mujumdar NR, Dudeja V, Clawson KA, Dawra RK, Saluja AK, Vickers SM. TRAIL and Triptolide: An Effective Combination that Induces Apoptosis in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1065-6. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiley SR, Schooley K, Smolak PJ, Din WS, Huang CP, Nicholl JK, Sutherland GR, Smith TD, Rauch C, Smith CA, et al. Identification and characterization of a new member of the TNF family that induces apoptosis. Immunity. 1995;3:6. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashkenazi A, Pai RC, Fong S, Leung S, Lawrence DA, Marsters SA, Blackie C, Chang L, McMurtrey AE, Hebert A, DeForge L, Koumenis IL, Lewis D, Harris L, Bussiere J, Koeppen H, Shahrokh Z, Schwall RH. Safety and antitumor activity of recombinant soluble Apo2 ligand. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:2. doi: 10.1172/JCI6926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keane MM, Ettenberg SA, Nau MM, Russell EK, Lipkowitz S. Chemotherapy augments TRAIL-induced apoptosis in breast cell lines. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walczak H, Miller RE, Ariail K, Gliniak B, Griffith TS, Kubin M, Chin W, Jones J, Woodward A, Le T, Smith C, Smolak P, Goodwin RG, Rauch CT, Schuh JC, Lynch DH. Tumoricidal activity of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in vivo. Nat Med. 1999;5:2. doi: 10.1038/5517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizutani Y, Yoshida O, Miki T, Bonavida B. Synergistic cytotoxicity and apoptosis by Apo-2 ligand and adriamycin against bladder cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basu A, Castle VP, Bouziane M, Bhalla K, Haldar S. Crosstalk between extrinsic and intrinsic cell death pathways in pancreatic cancer: synergistic action of estrogen metabolite and ligands of death receptor family. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frese S, Pirnia F, Miescher D, Krajewski S, Borner MM, Reed JC, Schmid RA. PG490-mediated sensitization of lung cancer cells to Apo2L/TRAIL-induced apoptosis requires activation of ERK2. Oncogene. 2003;22:35. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter BZ, Mak DH, Schober WD, Dietrich MF, Pinilla C, Vassilev LT, Reed JC, Andreeff M. Triptolide sensitizes AML cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis via decrease of XIAP and p53-mediated increase of DR5. Blood. 2008;111:7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panichakul T, Intachote P, Wongkajorsilp A, Sripa B, Sirisinha S. Triptolide sensitizes resistant cholangiocarcinoma cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:1A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slee EA, Adrain C, Martin SJ. Executioner caspase-3, -6, and -7 perform distinct, non-redundant roles during the demolition phase of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell-death proteases. Nature. 1997;388:6639. doi: 10.1038/40901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]