Abstract

Gliotoxin (1), a major product of the gli non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) gene cluster, is strongly associated with virulence of the opportunistic human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Despite identification of the gli cluster, the pathway of gliotoxin biosynthesis has remained elusive, in part because few potential intermediates have been identified. In addition, previous studies suggest that knowledge of gli-dependent metabolites is incomplete. Here we use differential analysis by 2D NMR spectroscopy (DANS) of metabolite extracts derived from gli knock-out and wild-type (WT) strains to obtain a detailed inventory of gli-dependent metabolites. DANS-based comparison of the WT metabolome with that of ΔgliZ, a knock-out strain devoid of the gene encoding the transcriptional regulator of the gli cluster, revealed nine novel gliZ-dependent metabolites including unexpected structural motifs. Their identification provides insight into gliotoxin biosynthesis and may benefit studies of the role of the gli cluster in A. fumigatus virulence. Our study demonstrates the utility of DANS for correlating gene expression and metabolite biosynthesis in microorganisms.

Filamentous fungi produce remarkably diverse metabolomes including many small molecules of polyketide synthase (PKS) or NRPS origin that play important roles in pathogenesis.1 The opportunistic pathogen A. fumigatus, a causative agent of invasive aspergillosis, produces copious amounts of gliotoxin (1), a representative member of a small family of epipolythiodioxopiperazines (ETP’s) that is strongly associated with A. fumigatus virulence.2 Gliotoxin and related ETP’s are products of the gli NRPS gene cluster.3 Knock-out mutations of gliP (ΔgliP), a three-module NRPS (see Figure S7 for domain architecture),3,4 gliI (ΔgliI), encoding a putative pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) binding domain,5 or gliZ (ΔgliZ), a Zn2Cys6 binuclear transcription factor, abolishes gliotoxin biosynthesis.6 ΔgliP has been shown to be significantly less virulent than the wild-type (WT) strain in immuno-suppressed mice,6c confirming that gliotoxin and perhaps other gli-dependent metabolites play a role in overcoming host resistance.

Previous studies suggest that knowledge of gli-dependent metabolites is incomplete.6d In addition, the sequence of steps in the biosynthesis of the gliotoxins has remained unclear, in part because few potential biosynthetic intermediates or shunt metabolites have been identified. We hypothesized that NMR-based comparative metabolomics of gli-knock-out and WT or gli-overexpressing strains could provide a comprehensive overview of gli-dependent metabolites, including shunt metabolites and other cryptic products.7 Recent studies, including the identification of bacillaene as the product of the mixed PKS/NRPS gene cluster pksX in Bacillus subtilis8 and the identification of mating pheromones in Caenorhabditis elegans,9 have demonstrated the utility of DANS for connecting metabolites with their biosynthetic pathways. In these examples, DANS combined with HPLC-MS analyses provided a comprehensive overview of the metabolic changes caused by knocking out small-molecule biosynthetic genes, which in each case led to the identification of several previously undetected metabolites derived from the knocked-out pathway.

For metabolic comparison, we used WT A. fumigatus and the mutant strain ΔgliZ.6d Knock-outs of gliZ have been shown to stop the expression of the majority of genes in the gli cluster with the exception of gliT.6d,10 Therefore, DANS-based comparison of the ΔgliZ and WT metabolomes should enable identification of any metabolites whose biosyntheses directly or indirectly depend on gli expression (Figure 1).

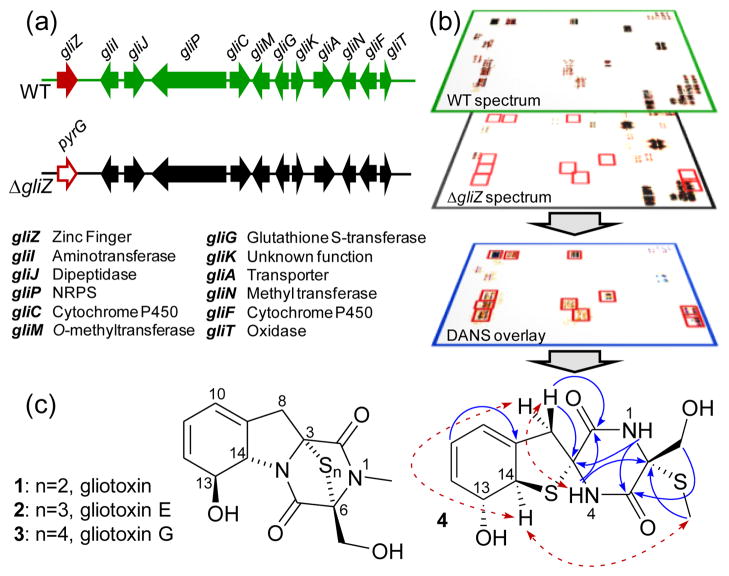

Figure 1.

Identification of gliZ-dependent metabolites via DANS. (a) Gliotoxin gene cluster in A fumigatus WT and mutant strain ΔgliZ, in which gliZ is replaced by the selection marker pyrG, encoding orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase. (b) DANS overlay technique (schematic). Signals in the DANS overlay serve as markers for compounds whose biosyntheses depend on gliZ-expression. (c) Examples for gliZ-dependent metabolites identified in this study and structure elucidation of 4 (HMBC: blue arrows; ROESY: red arrows).

In preparation for NMR-spectroscopic analyses, we fractionated both the ΔgliZ and WT metabolomes into three metabolite pools of reduced complexity and limited polarity range, which ensured that both very polar (pool # 1) and very non-polar (pool #3) metabolites would be detected (see methods in Supporting Information) For the resulting three WT pools and three ΔgliZ pools, we acquired high-resolution dqfCOSY spectra. Compared to other 2D NMR spectroscopic techniques such as TOCSY11 or HSQC,12 dqfCOSY spectra offer distinct advantages for the detection of novel or unanticipated compounds, because crosspeak fine structure in dqfCOSY spectra provides greater structural information, including full signal multiplicity and coupling constants.13 Furthermore, dqfCOSY crosspeak fine structures can be easily modeled,13 which helps resolve peak overlap and facilitates recognition of minor components.9 dqfCOSY spectra also offer better sensitivity than HSQC, often enabling characterization of trace components representing less than 0.1% of a sample.14

For DANS, dqfCOSY spectra obtained for the three WT metabolite pools were compared with the corresponding ΔgliZ pools using an overlay algorithm designed to highlight WT signals that were completely absent from the ΔgliZ spectra. This approach excluded compounds from the analysis whose biosynthesis was not entirely gliZ-dependent. DANS revealed more than twenty distinct gliZ-dependent spin systems in WT pool #2 (Figures 2, S1) and a smaller number of gliZ-dependent signals in WT pool #1. No gliZ-dependent signals were observed in WT pool #3.

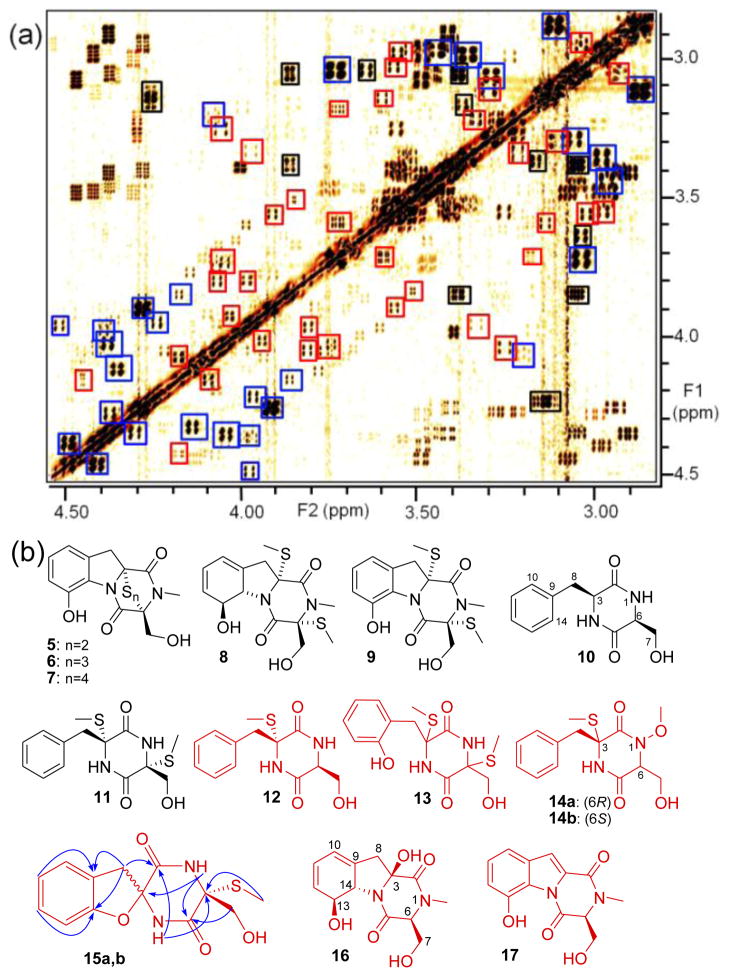

Figure 2.

Identification of gliZ-dependent metabolites in pool#2. (a) Section of the WT dqfCOSY spectrum. gliZ-dependent signals detected via DANS are boxed, representing known gliotoxin derivatives (blue), the known 10 and 11 (black), and novel compounds 12–17 (red). See Figure S1, Supporting Information, for DANS overlay spectrum. (b) gliZ-dependent metabolites identified in WT pool #2. Structures shown in red represent novel metabolites. The relative configuration of 13, which occurs as one single diastereomer, could not be determined, but likely corresponds to that of 11.

In the spectra of WT pool #1, DANS revealed two major gliZ-dependent spin systems which correspond to structural motifs also present in the gliotoxins, including an α-substituted serine and a 5,6-disubstituted cyclohexa-2,4-diene-1-ol bearing a methylene-group in position 5. However, chemical shift values and coupling constants indicated that this metabolite does not represent a known compound (Table S1). HR-MS revealed a molecular formula of C13H16N2O4S2 which, in conjunction with ROESY and HMBC data obtained for a purified sample, established the structure of 4 as shown, featuring a sulfur bridge between C-3 and C-14 as part of an unusual 6,9-diaza-1-sulfaspiro[4.5]decane system (Figure 1). Compound 4 is a novel metabolite with a structural motif rarely observed in nature, featuring a sulfur- and nitrogen-bound spiro atom. Notably, the configurations at C-13 and C-14 in 4 are opposite to those found in gliotoxin 1, assuming that the configurations at C-3 and C-6 in 4 are the same as in 1, which seems likely given that both 1 and 4 are 3,6-cis-disulfurized.

Analysis of gliZ-dependent signals in the WT pool #2 spectra revealed spin systems whose NMR data closely matched those of the known ETP’s 1–3 (Figure 1) and the bis-methylsulfanyl derivative 8,15 in addition to a large number of unknown compounds (Figure 2). For further structural assignments, we fractionated WT pool #2 via HPLC and characterized fractions containing one or more of the gliZ-dependent compounds detected by DANS, using HSQC, HMBC, and ROESY spectra as well as HPLC-MS. These analyses confirmed the presence of the gliotoxins 1–3 and 8, as well as their dehydroderivatives 5–7 and 9.15c, 16 We further identified cyclo(L-Phe-L-Ser) (10),17 not previously reported from A. fumigatus extracts nor other gliotoxin-producing fungi, as well as bis-N-norgliovictin (11), a known A. fumigatus metabolite18 not previously associated with the gli cluster.

All other gliZ-dependent metabolites detected in WT pool #2 represented novel compounds (Figure 2c). These include the four diketopiperazines 12–14. Compounds 14a/b represent diastereomeric N-methoxy derivatives of 12, as was shown via 1H, 15N-HMBC. These diketopiperazines are accompanied by two indolopyrazines 16 and 17, representing non-sulfurized derivatives of gliotoxin. In addition, DANS revealed a second type of spirocyclic scaffold, the 6,9-diaza-1-oxaspiro[4.5]decanes 15a and 15b. The two diastereomers 15a/b appear to be derived from 13 via intramolecular substitution at C-3, as isolated samples of 13 slowly convert into mixtures of 15a and 15b (Figure S6). HR-MS confirmed the molecular formulae of all new compounds (See Tables S1–S11 for spectroscopic data), and the gliZ-dependence of their biosynthesis was corroborated via DANS and HPLC-MS in two independent replicates (Figures S2, S3).

To test whether gliZ overexpression would reveal additional gliZ-dependent metabolites, we compared the A. fumigatus WT metabolome with that of a gliZ-overexpressing (OE) strain via DANS.6d Although we observed differences in the relative amounts of some of the metabolites 1–17 in the OE strain, we did not detect any new gliZ-dependent metabolites. Next, we investigated the effect of deletion of two additional gli genes, gliP and gliI. DANS- and HPLC-MS-based comparison of ΔgliP and ΔgliI mutant metabolomes with WT showed that none of the gliZ-dependent compounds 1–17 are produced by these two mutant strains. These results further support that biosynthesis of 1–17 requires the gli cluster.

Of the nineteen gliZ-dependent compounds we identified, nine represent novel compounds, several of which feature structural motifs not previously associated with gli products. These structural features are of interest considering the putative pathway of gliotoxin biosynthesis in A. fumigatus (Figure 3).3 Only the first and last steps in gliotoxin biosynthesis, the condensation between L-Phe and L-Ser by GliP and the oxidation of dithiol gliotoxin by GliT, have been elucidated,4,10a and many aspects of the intervening steps remain unclear. In vitro experiments conducted with recombinant GliP demonstrated that GliP couples the amino acids Phe and Ser, producing a Phe-Ser-GliP intermediate.4 Further observations indicated that GliP is capable of producing cyclo(L-Phe-L-Ser), but kinetic data suggested that the rate of cyclic dipeptide formation may be too low to be enzymatically relevant.4 Our studies show that 10 is a major component of the A. fumigatus WT metabolome, with a gliotoxin to cyclo(L-Phe-L-Ser) molar ratio of roughly 2:1, and that this abundant production of 10 is gliZ-dependent. The abundance of 10 suggests that the in vivo rate of formation is much greater than in vitro, perhaps due to presence of additional factors, for example other gli components, in vivo. It has been proposed that 10 is an intermediate in gliotoxin biosynthesis;5 however, the structural features of the gliZ-dependent metabolites we identified are consistent with pathways involving tethered intermediates (Figure 3). Furthermore, the addition of synthetic 10 to ΔgliP cultures did not rescue the production of any of the gliZ-dependent metabolites as assessed by DANS and HPLC-MS (Supporting Information), suggesting 10 may not be a biosynthetic intermediate.

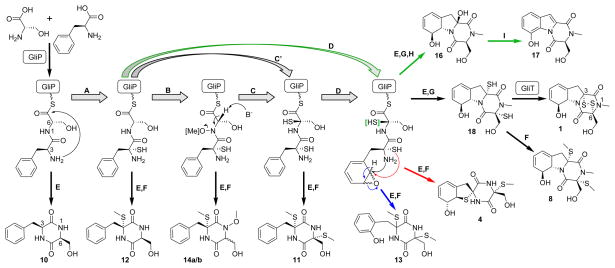

Figure 3.

Proposed biogenesis of gliZ-dependent metabolites. Oxidation and sulfurization at C-3 (A) is followed by N1-oxidation (B) and C-6 sulfurization (C or C′). Epoxidation (D) is followed by pyrollidine, thiophane, or phenol formation (black, red, and blue arrows, respectively). Aminolysis (E) of the resulting GliP-tethered intermediates and methylation of thiols (F) produces compounds 4,10–14a/b. N1-methylation (G) and aminolysis (E) results in formation of dithiol, which is S-methylated (F) to form 8 or oxidized by GliT10a to produce gliotoxin, 1. Hydrolysis (H) of species oxidized (and possibly sulfurized) only at C-3 (green arrows) produces 16 which aromatizes (I) to form 17.

All of the gliZ-dependent compounds 1–17 except 10 are oxidized at the α-carbon of Phe, and in the case of compound 12 only at that position, suggesting oxidation and sulfurization at C-3 occurs at an early stage in the biosynthesis following formation of the Phe-Ser dipeptide. Oxidation at C-3 could involve gliC or gliF, encoding putative cytochrome P450 monooxygenases. Alternatively, gliI, encoding a putative PLP cofactor domain characteristic of amino transferases,5 may function in transforming the free amino group of the Phe moiety into the corresponding imine, as previous studies suggested that installation of sulfur at the α-position of diketopiperazines may proceed via imine intermediates.19 Such a mechanism would be consistent with the hypothesis that gliotoxin biosynthesis proceeds via successive elaboration of a tethered dipeptide. Our finding that ΔgliI does not produce any of the gliZ-dependent compounds 1–17 does not allow distinguishing between these possibilities. However, the absence of all gliP-dependent metabolites from ΔgliI is consistent with the observation that gliP-transcription is abolished in this mutant (Figure S5). Sulfurization at C-3, yielding a C-3 thiol intermediate, likely involves GliG, recently demonstrated to posses glutathione S-transferase activity in vitro.19 Compound 12 would then form via methylation of the thiol, either before or after aminolysis of the thioester. All sulfurized diketopiperazines identified in this study (except for the four ETP’s), are S-methylated and thus likely derived from methylation of corresponding thiols, which is also suggested by the finding that in Gliocladium deliquescens gliotoxin is converted into bisdethiobis(methylthio)gliotoxin, 8.15c

The identification of compounds 11 and 14a/b suggests that sulfurization at C-3 is followed by oxidation of the peptide backbone at C-6 and N-1, with O-methylation of the resulting hydroxamic acid derivatives by the putative O-methyltransferase GliM. Aside from spirocyclic 15a/b, compounds 14a/b are the only gliZ-dependent metabolites that occur as a pair of epimers, likely as a result of deprotonation/enolization at C-6. Oxidation at C-6, perhaps involving gliC or gliF, could occur independently from hydroxylation of N-1; however, sulfurization at C-6 could also be accomplished via dehydration of a hydroxamic acid intermediate followed by sulfurization of the resulting imine, as had been proposed previously based on synthetic studies21 and a shunt metabolite detected in a ΔgliG strain.19 This mechanism is also suggested by the lack of N-hydroxylated or methoxylated compounds other than the C-6 non-sulfurized 14a/b. Release and methylation of the bis-3, 6-disulfurized dipeptide would then produce compound 11.

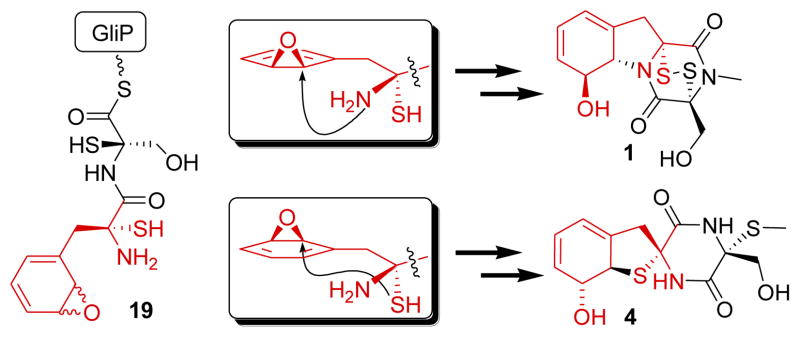

As a next step, the disulfurized dipeptide appears to undergo epoxidation of the phenyl ring by one of two putative cytochrome P450 monooxygenases, GliC or GliF. The relative configurations observed for compound 4 strongly suggest that this oxidation step is not entirely stereoselective and produces both the (13S,14-R)- and (13-R,14S)-diastereomers (Figure 4). Nucleophilic opening of the (13S,14R)-diastereomer by the C-3 amino group could lead to formation of the pyrrolidine ring of gliotoxin, whereas nucleophilic attack by the C-3 thiol results in formation of the thiophane ring in 4. Alternatively, the phenyl ring is oxidized to form the ortho-substituted phenol found in compound 13, perhaps via the shown epoxide intermediate. The bio-syntheses of 13, spirocyclic compound 4, and the gliotoxins (1–3 and 8) are completed via diketopiperazine formation and S-methylation (in case of 4 and 13) or N-methylation, possibly involving gliN, and epidi-thio-bridge formation via GliT in case of the EPT’s.10a Lastly, compounds 16 and 17, which both lack oxidation at C-6, appear to be derived from epoxidation of an intermediate oxidized only at C-3, followed by pyrrolidine and diketopiperazine formation. As the relative configuration at C-3 in 16 is opposite to that of C-3 in all identified C-3-sulfurized compounds, the C-3-OH group in 16 could be derived from substitution of a thiol or methylsulfanyl group. Elimination of water from 16 would form a dihydroindole that could easily aromatize to form 17.

Figure 4.

Different configurations of putative epoxide intermediate 19 result in formation of either gliotoxin (1) or spirocyclic 4.

Additional studies will be needed to test and further expand this model, to clarify the mechanism of sulfur incorporation,19 and to determine whether tethered intermediates or diketopiperazines are the substrates of the gli-encoded oxidases and methyltransferases. Furthermore, variation of growth conditions could induce biosynthesis of additional gliZ-dependent metabolites.

In conclusion, our comparison of the WT and ΔgliZ metabolomes via DANS revealed nine new compounds featuring several unexpected structural motifs, despite the fact that A. fumigatus’ metabolome, and specifically gliotoxin and its associated biosynthetic genes’ role in virulence, had already been studied extensively. In particular, DANS facilitated detection of minor or unstable metabolites (e.g. 4 and 13) missed by conventional analysis. Further investigations of the role of the gli-cluster in A. fumigatus virulence may benefit from the expanded knowledge of gli-associated structures and help clarify the biological roles of the newly identified compounds. Finally, our results suggest that the use of NMR-based comparative metabolomics for the examination of orphan PKS/NRPS gene clusters in microorganisms can significantly accelerate discovery of new structures and biosynthetic annotation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (GM079571, P41RR02301, and P41GM66326) and DuPont Crop Protection.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures, construction of mutants, NMR spectra for pool #2, HPLC chromatograms, and spectroscopic data. Complete ref 1. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Nierman WC, et al. Nature. 2005;438:1151. doi: 10.1038/nature04332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rohlfs M, Albert M, Keller NP, Kempken F. Biol Lett. 2007;3:523. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Kupfahl C, Michalka A, Lass-Florl C, Fischer G, Haase G, Ruppert T, Geginat G, Hof H. Int J Med Microbiol. 2008;298:319. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lewis RE, Wiederhold NP, Chi J, Han XY, Komanduri KV, Kontoyiannis DP, Prince RA. Infect Immun. 2005;73:635. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.635-637.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardiner DM, Howlett BJ. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;248:241. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balibar CJ, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15029. doi: 10.1021/bi061845b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox EM, Howlett BJ. Mycol Res. 2008;112:162. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Cramer RA, Jr, Gamcsik MP, Brooking RM, Najvar LK, Kirkpatrick WR, Patterson TF, Balibar CJ, Graybill JR, Perfect JR, Abraham SN, Steinbach WJ. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:972. doi: 10.1128/EC.00049-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kupfahl C, Heinekamp T, Geginat G, Ruppert T, Hartl A, Hof H, Brakhage AA. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:292. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sugui JA, Pardo J, Chang YC, Zarember KA, Nardone G, Galvez EM, Mullbacher A, Gallin JL, Simon MM, Kwon-Chung K. J Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:1562. doi: 10.1128/EC.00141-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bok JW, Chung D, Balajee SA, Marr KA, Andes D, Nielsen KF, Frisvad JC, Kirby KA, Keller NP. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6761. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00780-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Challis GL. J Med Chem. 2008;51:2618. doi: 10.1021/jm700948z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Forseth RR, Schroeder FC. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:38. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butcher RA, Schroeder FC, Fischbach MA, Straight PD, Kolter R, Walsh CT, Clardy J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610503104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pungaliya C, Srinivasan J, Fox BW, Malik RU, Ludewig AH, Sternberg PW, Schroeder FC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811918106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Scharf DH, Remme N, Heinekamp T, Hortschansky P, Brakhage AA, Hertweck C. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10136. doi: 10.1021/ja103262m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schrettl M, Carberry S, Kavanagh K, Haas H, Jones GW, O’Brien J, Nolan A, Stephens J, Fenelon O, Doyle S. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000952. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang F, Dossey AT, Zachariah C, Edison AS, Bruschweiler R. Anal Chem. 2007;79:7748. doi: 10.1021/ac0711586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan TW, Yuan P, Lane AN, Higashi RM, Wang Y, Hamidi AB, Zhou R, Guitart X, Chen G, Manji HK, Kaddurah-Daouk R. Metabolomics. 2010;6:165. doi: 10.1007/s11306-010-0208-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Claridge TDW. High-resolution NMR Techniques in Organic Chemistry. 2. Elsevier; Amsterdam; Boston: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Taggi AE, Meinwald J, Schroeder FC. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10364. doi: 10.1021/ja047416n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gronquist M, Meinwald J, Eisner T, Schroeder FC. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10810. doi: 10.1021/ja053617v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Fukuyama T, Nakatsuka S, Kishi Y. Tetrahedron. 1981;37:2045. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kirby GW, Rao GV, Robins DJ. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1988;1:301. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kirby GW, Robins DJ, Sefton MA, Talekar RR. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1980;1:119. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Safe S, Taylor A. J Chem Soc C. 1970;3:432. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hanson JR, Oleary MA. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1981;1:218. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campo VL, Martins MB, da Silva CHTP, Carvalho I. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:5343. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao WY, Zhu TJ, Han XX, Fan GT, Liu HB, Zhu WM, Gu QQ. Nat Prod Res. 2009;23:203. doi: 10.1080/14786410600906970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boente MIP, Kirby GW, Patrick GL, Robins DJ. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1991;1:1283. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis C, Carberry S, Schrettl M, Singh I, Stephens JC, Barry SM, Kavanagh K, Challis GL, Brougham D, Doyle S. Chem Biol. 2011;18:542. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herscheid JDM, Nivard RJF, Tijhuis MW, Ottenheijm HCJ. J Org Chem. 1980;45:1885. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.